Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

2

Transféré par

Zeynab AbrezDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

2

Transféré par

Zeynab AbrezDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Reverse Image Transfer: Does the Product Endorsed Matter for Celebrity Athlete Endorsers?

Jan Charbonneau, Massey University and Ron Garland, Waikato University Introduction Having celebrity athletes endorse brands is a prominent part of many companies promotional strategies. The benefits that accrue to brands from such celebrity endorsement are well documented (see, for example, Kamins 1990; Erdogan 1999; James & Ryan 2001; Pornpitakpan 2003) and the academic literature is quite voluminous. The primary focus in the literature has been on the transfer of pre-existing celebrity image onto endorsed product or brand. Few studies, apart from that of Till (2001) in the USA, have investigated the influence of the pre-existing brand or product image upon the image of the celebrity athlete endorser in essence, reverse image transfer. This paper investigates reverse image transfer and closely replicates the work of Till (2001), albeit it in a New Zealand setting, using international celebrity athletes. Keywords: athletes; celebrities; endorsers; advertising Literature Review Undoubtedly, celebrity endorsers break through media clutter, hold viewers attention (Dyson & Turco 1998; Erdogan & Baker 1999), contribute to brand name recognition, create positive associations with the brand, and assist in developing distinct and credible brand personalities (Kamins 1990; Ohanian 1990). As public interest and media coverage has intensified, peak

performing athletes are increasingly regarded as viable and valuable celebrity endorsers.

Celebrity athletes provide particularly compelling testimonials for products that have contributed to their sporting performance and success (Stone, Joseph & Jones 2003). Atkin & Black (1983) traced the use of celebrity athletes in advertising post World War Two through to the 1970s, noting the positive impact athletes provided to a range of goods and services. Attitude changes in the positive direction were accredited to the presence of a celebrity such as an athlete as product endorser. Kahle & Homer (1985) extended this research perspective, being among the first to formally acknowledge how attractive endorsers, can produce attitudinal change among viewers.McCracken (1989) developed the Meaning Transfer Model to explain how pre-existing celebrity images consisting of symbolic and cultural meanings such as status, class and lifestyle transfer first from the celebrity to the product and then from the product to the consumer. If this concept of meaning transfer can be reversed, then it is possible for endorsed brands to attach some of their pre-existing underlying image to the celebrity endorser. Hence we posit, as Till (2001) did, that in this age of celebrity athletes pursuing their own branding opportunities, the potential for reverse image transfer (from product or brand back to endorser) should be considered when evaluating endorsement opportunities.

Among the more persuasive and widely used of the models developed for exploration of product (brand) celebrity match-up is the source-credibility model. This model suggests that message effectiveness depends on the endorsers perceived credibility, with credibility being a combination of both expertise and trustworthiness. In 1990, Ohanian added perceived attractiveness to the basic source credibility model and so developed the combined sourcecredibility model that forms the basis of the evaluative measures used in this paper. Till (2001) demonstrated how endorsers own images can be adversely affected by association with negatively perceived products, such as tobacco with their well documented health risks. This form of reverse image transfer the impact of the pre-existing brand image on the endorser is worthy of investigation and of value to celebrities and athletes in matching their own brands (themselves) with potential endorsement opportunities, making appropriate selections to preserve or potentially improve their own brand image. Methodology This study is a close replication of Tills (2001) American study with slight adjustments for the New Zealand environment. The hypothesis to be tested (derived from Tills 2001 work) was that while a positively perceived product will have little or no effect on respondents perceptions of celebrity athlete endorsement, a negatively perceived product will have a substantial effect. Following extensive pre-testing, Till selected orange juice and chewing tobacco as the anchor products for the positive-negative product continuum used in his research. Orange juice was validated in New Zealand pre-tests as a positive product. As New Zealanders do not have a tradition of chewing tobacco, cigarettes were used in this study. Pretesting revealed a sufficient level of negative connotations for cigarettes in New Zealand. To remove any specific confounding branding influences in the experiment, the two products, orange juice and cigarettes, were presented to respondents as Brand X orange juice and Brand X cigarettes. To remove the chance of effect from choice of endorser, Till (2001) created fictitious endorsers. In this study, we created two fictitious endorsers, one male (named Marty) and one female (named Franny) to test for gender effects. As rugby football is New Zealands national winter game, played by both men and women, Marty and Franny were created as elite rugby athletes. To extend Tills work, we chose Anna Kournikova and David Beckham from the world of sport representing athletes as their own brands. Both have general public name and face recognition and earnings from their endorsement activities far exceed their incomes from sport prize money. These decision outcomes discussed above resulted in two experiments: Comparison of two fictitious celebrity rugby players (one male, one female) endorsing two generic products (Brand X orange juice and Brand X cigarettes) Comparison of two named celebrity athletes (David Beckham and Anna Kournikova representing athletes as their own brands) endorsing the same two generic products. Eight versions of our questionnaire were constructed as follows: Version 1: Generic athlete Marty endorsing Brand X orange juice Version 2: Generic athlete Marty endorsing Brand X cigarettes Version 3: Generic athlete Franny endorsing Brand X cigarettes Version 4: Generic athlete Franny endorsing Brand X orange juice Version 5: Branded athlete David Beckham endorsing Brand X orange juice

Version 6: Version 7: Version 8:

Branded athlete David Beckham endorsing Brand X cigarettes Branded athlete Anna Kournikova endorsing Brand X orange juice Branded athlete Anna Kournikova endorsing Brand X cigarettes

Background information provided in the questionnaires for the generic rugby players Marty and Franny was restricted to Marty was a professional rugby player who represented his country at the 2003 World Cup. He was acclaimed by his teammates as one of the best players in his position and Franny was a rugby player who represented her country at the 2002 World Cup. She was acclaimed by her teammates as one of the best players in her position. Background information provided in versions 5-8 of the questionnaire for David Beckham and Anna Kournikova was restricted to: David Beckham is Englands former football captain and played for Manchester United before moving to Real Madrid and Anna Kournikova, the Russian tennis star is the winner of many doubles tournaments. The research instruments for each product (orange juice and cigarettes) and each subject (celebrity both fictitious and branded) contained three black and white print ads, mocked up with the subjects in casual clothing, a photograph of the product and the following copy: (Subject) ONLY drinks BRAND X orange juice (Subject) ONLY drinks BRAND X, the juice with more orange! (Subject) and BRAND X orange juicea winning combination! (Subject) ONLY smokes BRAND X cigarettes (Subject) ONLY smokes BRAND X the cigarette with more PUFF! (Subject) and BRAND X cigarettesa winning combination!

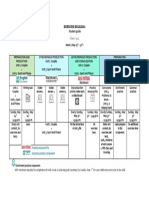

Ohanians (1990) source-credibility scale was adopted to evaluate our samples perceptions of each celebritys attractiveness and trustworthiness both before and after the product match-up experiment (see Figure 1). Apart from her own validity and reliability testing in 1990 and 1991, Ohanians scale has been tested in a number of non-US settings (see, for example James & Ryan (2001); Garland & Ferkins (2003); Pornpitakpan (2003)). We chose to use only the first ten attributes of Ohanians 15 point semantic differential source-credibility scale because the final five points are expertise attributes and our selected athletes were all either independently judged or created by us as experts in their sport of choice. Respondents were all undergraduate business students from Massey University, New Zealand. The research was carried out at the beginning of marketing research, marketing management and consumer behaviour lectures without any prior publicity. Once completed (and collected) aspects of the survey were incorporated into lecture content. Students were judged to be an appropriate sample for this experiment as they are often market innovators (Nikas 1999) and are the target market for many of the products that have used celebrity athletes as endorsers. In total 240 respondents (n=128 males; n=112 females) completed our survey, split equally into eight groups with n=30 respondents receiving one of the eight versions (see above). Figure 1. Ohanians 15-point source-credibility scale (adapted by authors)

Attractiveness

Unattractive-Attractive Not Classy-Classy Ugly-Beautiful Plain-Elegant Not Sexy-Sexy

Trustworthiness

Not Dependable-Dependable Dishonest-Honest Unreliable-Reliable Insincere-Sincere Untrustworthy-Trustworthy

Expertise

Not Expert-Expert Inexperienced-Experienced UnknowledgeableKnowledgeable Unqualified-Qualified Unskilled-Skilled

Respondents completed several demographic questions, a level of interest in sport question and then a screening question on perceived level of appropriateness (using a 9-point semantic differential scale: anchors not appropriate; appropriate) for an athlete to endorse orange juice or to endorse cigarettes. The celebrity athlete (either generic or named) was then presented to respondents by way of a PowerPoint slide with a picture and the brief biography specified above. Respondents scored their subject on ten attributes of the Ohanian (1990) 15point source-credibility scale. Respondents were then exposed to the three print ads in randomized order (for each celebrity athlete paired with his/her particular product) with the viewing pace controlled by the authors as they administered the questionnaire. After viewing was complete, respondents completed the same evaluation (again using ten of the 15 attributes of Ohanians source-credibility scale) for their celebrity athlete as before, completing the before exposure, after exposure experiment. Results and Discussion At the beginning of the questionnaire respondents scored athletes in general (using a ninepoint semantic differential scale) as to perceived appropriateness to endorse orange juice or cigarettes. This initial question provided context in the form of a benchmark result for the experimentation to follow. Results of these benchmarks are presented in Table 1 and are unequivocal. Orange juice is an appropriate product for celebrity athletes to endorse; cigarettes are not! This further validates the selection of orange juice as a positively perceived product and cigarettes as a negatively perceived product. Table 1. Celebrity athlete appropriateness to endorse orange juice, cigarettes Product Orange juice Cigarettes Mean 7.09 1.86 Std deviation 1.57 1.73 Sample size 237 234

Our main hypothesis was that the endorsement of a positive product (orange juice) would have little or no effect upon a celebrity athletes perceived credibility but endorsement of a negatively perceived product (cigarettes) would result in a negative impact on perceived credibility. Table 2 displays the grand means for each treatment (version) and demonstrates clearly that the endorsement of orange juice by either a generic celebrity athlete or a named celebrity athlete had little or no effect as hypothesised, consistent with results from Till (2001). Equally as clear is the denigration of celebrity athlete credibility through endorsement of cigarettes, again consistent with the findings by Till (2001). The change in respondents evaluations brought about by pairing generic and named celebrity athletes with cigarettes in mock-up print ads was always in the negative direction (see treatments 2,3,6,8 in Table 2) in each of these cases mean evaluations fell by statistically significant amounts (at the .05 level). Perhaps of even more interest is the harsher evaluations meted out to female athletes (compared to males) when endorsing cigarettes (the sample was roughly split between males and females).

Table 2. Evaluation of celebrity athletes by product category Pre-test Mean 1. Generic male athlete Orange juice 4.45 2. Generic male athlete Cigarettes 4.58 3. Generic female athlete Cigarettes 5.21 4. Generic female athlete Orange juice 5.13 5. David Beckham Orange juice 5.05 6. David Beckham Cigarettes 4.67 7. Anna Kournikova Orange juice 5.21 8. Anna Kournikova Cigarettes 5.32 * Statistically significant at .05 level on simple ANOVA. Treatment (n=30 each) Product Post-test Mean 4.49 4.20 4.69 5.23 4.84 4.32 5.33 4.67 T -.24 2.19 3.83 -1.39 1.49 2.41 -.88 3.74 p .82 .04* .01* .18 .15 .03* .39 .01*

Investigation of particular attributes of source-credibility (see Table 3) reveals that respondents were especially harsh in their scoring of the athletes on the trustworthiness dimensions attributes (dependability, honesty, reliability, sincerity and trustworthiness) when they were paired with the negative product, cigarettes. Nevertheless, interesting side issues emerge on closer inspection of the scores for the two named celebrity athletes. It would appear that Anna Kournikova is dealt particularly severe evaluations when associated with cigarettes, stemming from decreasing values for attributes in both dimensions (attractiveness and trustworthiness). David Beckham however is perceived less severely although he too loses some appeal on the trustworthiness dimension. The generic female athlete scores are similar to those for Anna Kournikova leading us to speculate that associating with a negatively perceived product poses greater risks for female athletes than male athletes (in keeping with our previous finding). Table 3. Celebrity athletes and cigarettes: attributes of attractiveness & trustworthiness Generic male Generic female Beckham athlete athlete Pre-test Post- Pre-test Post- Pre-test Postmean test mean test mean test mean mean mean Attractiveness 5.07 4.70 5.57 5.30 4.77 4.60 Classiness 4.87 4.30* 4.87 4.63 5.00 4.30* Beauty 4.90 4.50* 5.70 5.40 4.63 4.40 Elegance 4.73 4.30* 5.07 4.60* 4.80 4.63 Sexiness 4.43 4.21 5.23 5.10 4.73 4.47 Dependability 4.37 4.23 5.20 4.53* 4.50 4.27 Honesty 4.23 4.03 5.13 4.40* 4.47 4.23 Reliability 4.57 3.97* 5.10 4.41* 4.57 4.03* Sincerity 4.37 3.83* 5.10 4.31* 4.73 4.17* Trustworthiness 4.27 3.90 5.17 4.20* 4.50 4.07* * Statistically significant at the .05 level on simple ANOVA. Ohanians (1990) attributes Kournikova Pre-test mean 6.17 5.31 5.97 5.76 6.43 4.77 4.83 4.76 4.90 4.87 Posttest mean 5.40* 4.38* 5.60* 4.97* 6.03 4.30 4.27* 3.86* 4.03* 3.90*

These results, comparable to those found by Till (2001), have implications for athletes, their agents and their corporate partners when endorsement opportunities are being evaluated. Choice of product for endorsement does matter in that reverse transfer can occur, suggesting

the need to test pre-existing product/brand images. As celebrity athletes such as David Beckham and Anna Kournikova increasingly derive substantial amounts of their income from brand endorsement or even try to reinvent themselves as brands in their own right, the potential for reverse image transfer needs to be factored into their endorsement decisions References Atkin, C. and Block, M. 1983. Effectiveness of celebrity endorsers. Journal of Advertising Research, vol. 23, no.1, pp.57-61. Dyson, A & Turco, D 1998. The state of celebrity endorsement in sport. Cyber-Journal of Sport Marketing, vol 2, no.1, viewed October 20, 2003, Available from Internet <http://www.ausport.gov.au/fulltext/1998/cjsm>. Erdogan, B 1999. Celebrity endorsement: A literature review. Journal of Marketing Management, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 291-314. Erdogan, B & Baker, M 1999. Celebrity endorsement: Advertising agency managers perspective. Cyber-Journal of Sport Marketing, vol.3, no. 3, viewed October 20, 2003, Available from Internet <http://www.ausport.gov.au/fulltext/1999/cjsm>. Garland, R & Ferkins, L 2003. Evaluating New Zealand sports stars as celebrity endorsers: intriguing results. Proceedings of ANZMAC Conference, University of South Australia, Adelaide, December, pp.122-129. James, K & Ryan, M 2001. Attitudes toward female sports stars as endorsers. Proceedings of ANZMAC Conference, Massey University, Auckland, pp. 1-8. Kahle, L. & Homer, P, 1985. Physical attractiveness of the celebrity endorser: a social adaptation perspective. Journal of Consumer Research. Vol.11, no.3, pp. 954-961. Kamins, M 1990. An investigation into the match-up hypothesis in celebrity marketing: when beauty may be only skin deep. Journal of Advertising, vol.19, no.1, pp. 4-13. McCracken, G 1989. Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 310-321. Nikas, C 2000. Just Ad Celebrity. Ragtrader, May 5-18, pp. 22-23. Ohanian, R 1990. Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 39-52. Ohanian, R 1991. The impact of celebrity spokespersons perceived image on consumers intention to purchase. Journal of Advertising Research, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 46-55. Pornpitakpan, C 2003. Validation of the celebrity endorsers credibility scale: Evidence from Asians. Journal of Marketing Management, vol. 19, no.1/2, pp. 179-195. Till, B 2001. Managing athlete endorser image: the effect of endorsed product. Sport Marketing Quarterly, vol. 10, no.1, pp. 35-42.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1091)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Statement of PurposeDocument13 pagesStatement of Purposemuhammad adnanPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Adrienne D Hunter - Art For Children Experiencing Psychological Trauma - A Guide For Educators and School-Based Professionals-Routledge (2018)Document321 pagesAdrienne D Hunter - Art For Children Experiencing Psychological Trauma - A Guide For Educators and School-Based Professionals-Routledge (2018)Sonia PuarPas encore d'évaluation

- Orthoptic ExcercisesDocument6 pagesOrthoptic ExcerciseskartutePas encore d'évaluation

- C V C V C V C V: Urriculum Itae Urriculum Itae Urriculum Itae Urriculum ItaeDocument1 pageC V C V C V C V: Urriculum Itae Urriculum Itae Urriculum Itae Urriculum ItaeFandrio PermataPas encore d'évaluation

- Pakistan International Airlines InternshipDocument67 pagesPakistan International Airlines Internshipmoeen7175% (4)

- Building ConnectionsDocument9 pagesBuilding ConnectionsMitch LaoPas encore d'évaluation

- P. E. Bull - Posture & GestureDocument190 pagesP. E. Bull - Posture & GestureTomislav FuzulPas encore d'évaluation

- Can Threatened Languages Be Saved PDFDocument520 pagesCan Threatened Languages Be Saved PDFAdina Miruna100% (4)

- Accounting AssignmentDocument2 pagesAccounting AssignmentZeynab Abrez0% (1)

- Sears Auto CentersDocument4 pagesSears Auto CentersZeynab AbrezPas encore d'évaluation

- Uhammad Ubashr Ussain: Ducation UalificationsDocument2 pagesUhammad Ubashr Ussain: Ducation UalificationsZeynab AbrezPas encore d'évaluation

- Usmaan Ali KhanDocument1 pageUsmaan Ali KhanZeynab AbrezPas encore d'évaluation

- SOC Final July December 2014 For OSC Approval AHB 3 After Additions and DelitionsDocument26 pagesSOC Final July December 2014 For OSC Approval AHB 3 After Additions and DelitionsZeynab AbrezPas encore d'évaluation

- XYLYS: Exploring Consumer Perception About Premium Watches in The Indian ContextDocument15 pagesXYLYS: Exploring Consumer Perception About Premium Watches in The Indian ContextZeynab AbrezPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter - 5 Measuring Market OpportunitiesDocument22 pagesChapter - 5 Measuring Market OpportunitiesZeynab AbrezPas encore d'évaluation

- Starbucks: Delivering Customer Service: Group Members: Umair Islam Maryam Khan Ahmed Mela Zubair NasirDocument12 pagesStarbucks: Delivering Customer Service: Group Members: Umair Islam Maryam Khan Ahmed Mela Zubair NasirZeynab AbrezPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Guidelines-Mahvesh Mahmud-Operations ManagementDocument7 pagesProject Guidelines-Mahvesh Mahmud-Operations Managementsarakhan0622Pas encore d'évaluation

- Presentation InstructionsDocument1 pagePresentation InstructionsZeynab AbrezPas encore d'évaluation

- Advanced Corporate Finance - Project DetailsDocument1 pageAdvanced Corporate Finance - Project DetailsZeynab AbrezPas encore d'évaluation

- Hertfordshire County Council Person Specification Form: Skills and AbilitiesDocument2 pagesHertfordshire County Council Person Specification Form: Skills and AbilitiesZeynab AbrezPas encore d'évaluation

- Advice To Young SurgeonsDocument3 pagesAdvice To Young SurgeonsDorelly MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- Developing Emotional IntelligenceDocument9 pagesDeveloping Emotional IntelligenceAnurag SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Security Assessment and TestingDocument43 pagesSecurity Assessment and Testingsubas khanalPas encore d'évaluation

- Ued 495-496 Davis Erin Lesson Plan 1Document11 pagesUed 495-496 Davis Erin Lesson Plan 1api-649566409Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 13 (Managing TheDocument14 pagesChapter 13 (Managing TheGizelle AlviarPas encore d'évaluation

- Alix R. Green (Auth.) - History, Policy and Public Purpose - Historians and Historical Thinking in Government-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2016)Document152 pagesAlix R. Green (Auth.) - History, Policy and Public Purpose - Historians and Historical Thinking in Government-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2016)Reza Maulana HikamPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Coordinatorship Action PlanDocument3 pagesSample Coordinatorship Action PlanShe T. JonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Research Papers On ManagementDocument5 pagesIndian Research Papers On Managementafeaqzhna100% (1)

- I4 SG Week 2Document1 pageI4 SG Week 2Ziyang Huaman BazanPas encore d'évaluation

- ADOPTIONDocument14 pagesADOPTIONArgell GamboaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cengiz Can Resume 202109Document2 pagesCengiz Can Resume 202109ismenhickime sPas encore d'évaluation

- What Are The RulesDocument1 pageWhat Are The RulesLouise Veronica JosePas encore d'évaluation

- Exploring Factors Influencing The Non-Completion of Theses Among Teachers Pursuing A Master's Degree: A Case Study AnalysisDocument10 pagesExploring Factors Influencing The Non-Completion of Theses Among Teachers Pursuing A Master's Degree: A Case Study AnalysisPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Notre Dame of Jaro, Inc. Vision:: Msgr. Lino Gonzaga ST., Jaro, LeyteDocument3 pagesNotre Dame of Jaro, Inc. Vision:: Msgr. Lino Gonzaga ST., Jaro, LeyteVia Terrado CañedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Differentiated LearningDocument27 pagesDifferentiated LearningAndi Haslinda Andi SikandarPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan F4 (19 - 4)Document5 pagesLesson Plan F4 (19 - 4)aisyah atiqahPas encore d'évaluation

- Cdev 2 Child and Adolescent Development 2Nd Edition Spencer A Rathus Full ChapterDocument51 pagesCdev 2 Child and Adolescent Development 2Nd Edition Spencer A Rathus Full Chapterdarrell.pace172100% (18)

- Julian Sowa General ResumeDocument1 pageJulian Sowa General Resumeapi-336812856Pas encore d'évaluation

- Virtual AssistantDocument3 pagesVirtual AssistantscribdbookdlPas encore d'évaluation

- Form Ac17-0108 (Application Form) NewformDocument2 pagesForm Ac17-0108 (Application Form) NewformEthel FajardoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of External Assistance in Enhancing The Innovation Capacity To MSMEs in West Java, IndonesiaDocument6 pagesThe Role of External Assistance in Enhancing The Innovation Capacity To MSMEs in West Java, IndonesiaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study - Challenger Ethical IssuesDocument7 pagesCase Study - Challenger Ethical IssuesFaizi MalikzPas encore d'évaluation

- Topic 9 Remedial and EnrichmentDocument13 pagesTopic 9 Remedial and Enrichmentkorankiran50% (2)