Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Rosalind E. Krauss - Photography in The Service of Surrealism

Transféré par

郭致伸Description originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Rosalind E. Krauss - Photography in The Service of Surrealism

Transféré par

郭致伸Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Art of the Twentieth Century

A Reader

Edited by Jason Gaiger and Paul V'iood

Yale Uni versity Press) New Haven and Lundon

in association with The Open University

-- I \ .

o J'{U,O'It,

-'1 "10

f'l r HlLj

This volume accompanies the Open Univer sity course Art of the Twentieth

Century, which examines the fundamental changes that took place in the concepts

and practices of art during the last century. There are four other books in the series,

all published by Yale University Press in association with the Open Uni \Cersity:

Frameworksfor Modern Art, edited by Jason Gaiger

T he A rt of the Avanl-Gardes, edited by Steve Edwards and Paul ''''ood

Varietz"es of M odernism, edited by Paul 'Wood

T hemes in Contemporary "Irt, edi ted by Gill Perry and Paul Vrood

Jason Gaiger is a Lecturer in the History of Art at the Open University.

Paul 'Wood is a Senior Lecturer in the History of An at the Open University.

First published 2 0 03

Copyright @) 2003 select ion and editorial ma[ter, The Open University; individual

items, the contributors.

The publishers have m ade every effon to trace the relevant copyright hol ders to

cl ear permissions. If any have been inadvertently omitted this is deeply regretted

and win be corrected in any fulure pr inting.

All rights reserved. T his book may not be reproduced in '\\"hole or in part, in any

for m (beyond that copying per mi t ted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright

Law and except by r eviewers for the public press), ""rithout wr itten permissi on from

the publisher s.

For information about thjs and other Yale University Press publications, please

contact:

U.S. Offi ce: saleS@preSS@yale.edu yalebooks.com

Europe Offi(:c: sales@yaJeup.co.uk ww'\\'.yalebooks.co.uk

Printed in Great Britain by BiddIes Ltd.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2003 1146'29

ISBN 0 - 300- 10 144- 9

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

COt\TENTS

Acknowledgements

A Note on the Presentat ion and Editing of T",lS

List of Illustrations

IX

X

Xl

Introduction XIX

I Modernism and the Crisis of Modernism

Introduction

3

Select ion of statemellts on early modernism

4

(i) Clive Bell

'Si rnpl ifi cat.ion and Design" 191 3

4

(ii) Roger Fry

'Negro Sculpture" 1920

(iii ) Carol a Gi edion-Welcker

from lVl odern Plastic A rt, 1937

10

(iv) Robert Goldwater

'A Defini tion of Primitivi sJn\ 1938

,6

( v) Shel don Cheney

from The Story if Modern A rt, '941

18

(vi) Elaine de Kooning

' Stateln ent', 1959

20

2 Meyer Schapi ro

'T he Nature of Abstract Art' , 1937

22

115

ART OF THE TWE.."TlETH CENTURY: A READH'\

"4

manner, as naturally and clearly as one could desire. Furthermore. pho

tomontage conti nues to be the best aid for photoreportage.

Filla])y. I come to what can be termed, in opposition to the 'applied' pho

tomontage that we have been discussing up to this point, 'free-form pho

tomontage,' that is, an art form that has grown out of the soil of photography.

T he peculiar characteristics of photography and its approaches have opened up

a new and im_mensely fantasljc field for a creative human being: a new, magi_

cal territory, for the di scovery of which freedom is the first prerequisite. BUL

not lack of disci pline, however. Even these newly discovered possibil iti es

remain subject to the laws of form and color in creating an iJ1tegral image sur

face. VVhenever we want to force this ' photomatter' to yield new for ms. w('

must be prepared for a journey of discovery. we must start without any prf'

conceptions; most of aU, we must be open to the beauties of fortuity. Here

more than anywhere else, these beauties, wandering and extravagant, oblig

ingly enrich our fantasy.

3. Rosalind Krauss, 'Photography in the

Service of Surrealism'

In t his essay. originally written to accompany the exhi bition 'L'Amour fou'.

Photography and Surrealism at the Hayward Gallery, London in 1986.

Rosali nd Krauss maintains that 'surrealist photography is the great

unknown. undervalued aspect of surrealist pract ice, but that nonetheless, it is

the great production of the movement'. She starts out with the identification

of a seemi ng paradox: how can photography, with its di rect, photomechani

cal trace of the real. be employed in t he service of Surrealism's project of reor

ganising our very conception of reality? She shows that the various mani pu

lations to which photography was subjected in Surrealism, including dou

blings. spaci ngs, close-ups and cropping, allowed the Surrealists to interrupt

photography' s apparently seamless relati on wit h reality. These techniques

inscribed photography with in the realm of language or signification, rather

than that of a causal imprint or 'index' of reali ty. At the same time, however.

Surrealist photographers exploited photography's privileged connection with

the real in order to 'convulse reality from within' and to show that reality itself

is already 'configured or coded or wri tten'. The essay is repinted in full from

Rosalind Krauss and Jane Livingston, 'L'Amour fou' . Photography and

Surrealism, exhi bition catalogue, Hayward Gallery/Arts Council of Great

Britain, London, 1986, pp. 15-42. We have only been able to reproduce a

limited selection of the photographs that origi nally accompanied this text. and

have renumbered the endnotes.

PART THREE: MODERt"ITY PHOTOGRAPHY

IFhen lllill we have sleepLIIg logicians, sleeping philosophers? J would like to sleep, in

order to sW7-ender myself to the dreamers ..

- J\1Wlifesto of Surrealism1

I-Jere is a paradox. It would seem that there cannot be surrealism and pho

tography, but only surrealjsm or photography. For surrealjsm was defined

from t he start as a revol ution in values, a reorganization of the very way the

real was conceived. Therefore, as its leader and founder, the poet Andre

Breton, declared, 'for a total revision of real values, the plastic work of art wi ll

(,ither refer to a purely internal model or will cease t.o These internal

models were assembled when consciousness lapses. I n dream, in free associa

tion, in hypnotic states, in automatism, in ecstacy or delirium, the ' pure cre

ations of the mind' 'were able to erupt.

Now, if painting might hope to chart these depths, phoLOgraphy would

seem most unlikely as a medi um. And indeed, in the Firsl N/anifeslo oj

Surrealism (192+). Breton's aversion to ' the real fo rm of real obj ects' express

es itseU in, for e.xample, a dislike of the literary realism of the nineteenth

century Dove] disparaged, precisely, as photographic. 'And the descriptions!' he

depl ores. compares to their nonentity; they are simply superilTIposed

pictures taken out of a catalogue, the author ... takes e\'ery opportunity to

slip me these postcards, he tries to make me see eye to eye with him about t he

obvious.'5 Breton's own 'novel' IVadj(l, (1928). which was copi ously illustrated

with photographs exactly to obvi ate the need for such wTi tten descri ptions,

di sappointed its author as be looked at its 'illustrated part. ' For the photo

graphs seemed to him to leave the magical places he had passed through

stripped of their aura, turned 'dead and disillusioning.'4

But that did not stop Breton from continuing to act on the call he had issued

in 1925 when he demanded. 'and when wi ll all the books that are worth any

rhing stop being illustrated with drawings and appear only with photo

grapbs?'5 The photographs by Man Ray and BrassaY that had ornamented the

secti ons from the novel .L'Amourfou ( 1937) that had fi rst appeared in the sur

realist periodical lWillolaure survived in the final veTsion, fai thfully keyed to

the text with those 'word-for-word quotations . .. as in old chambermaid's

books' that had so fascinated the cri tic ' Valter Benjamin when he thought

about their anomolous presence. Thus in one of the most centTal articulations

of the surrealist exrperience of the 1930s. photography continued, as Benjam,in

said, to 'intenene.'6

Indeed) it had intervened all during the 1920S in tlle journals published by

the movement, journals that continually sen'ed to exemplify. to define, to man

ifest, what it was that was surreal. :\1an Ray begins in La Revolulion sun-ealisle,

contributing six photographs to the first issue alone, to be joined by those sur

realist artists like Magrittc who were experimenting in photomontage and later,

in Le Surrealisme au sel'1;ice de fa revolulion, by Breton as well. Tn Docwnenls it

.,6 ART OF T I-fE A R.EADER

was Jacques-Andre Boiffard who manifested the sensibility photographically.

And by the time of Minolaure's operation. i\l an Ray was working along with

Raoul Ubac and BrassaL But the issue is not just that these books and journals

contamed photographs - or tolerated t hem, as it werc. The more important fact

is that in a few of these photographs surrealism achieved. some of its supreme

images - images of far greater power t han most of what was done in the

remorselessly labored paintings and drawings that came increasingly to estab

lish the identi ty of Breton's concept of Isurrealism and painting.'

If we look at certain of t hese photographs, we see with a shock of recog

nition the simul taneous effect of displacement and condensation, the vcry

operations of symbol format ion, hard at work on the fl esh of the rcal. In

iVian Ray' s Monument aD. /I. F de Sade, for example, our percept ion of

nude buttocks is guided by an act of rotation, as the cruci form inner 'fra me

for this image is tra nsformed into the fi gure of the phallus [Plate 14]' The

sense of capture that is simultaneously impl ied by this fall is then height

ened by t he structural reciprocity between frame and image, container a nd

contained. F'or it is th e frame that counteracts the effects of the light ing on

the flesh. a luminous intensity that causes the nude body to dissolve as it

moves with increasi ng insubstantiabty toward the edges of the sheet, seem

ing as it goes to become as t hin as paper. Only the cruciform edges of t he

frame, rhyming " ..jth the clefts and folds of the photographed anatomy,

serve to reinject this field wit h a sense of the corporeal presence of the body.

guarantying its density by the act of drawing limits. But to caJl this body

into being is to eroticize it forever, to freeze it as the symbol of pl easur e. In

a variation on th is theme of limi ts, J\1an Ray's untitled Minotaure imagc

displaces t he visually decapit..:'lted head of a body downward to transfo r m t he

recorded torso into the face of an animal. And the cropping of t he i_mage by

the photographic frame, a croppi ng that defines the bull 's physiognomy by

the act of locating it, as it were - this cutt ing mimes the beheading by shad

ow t hat is at work insjde the image's fi eld. So that in bot.h these photographs

a transformation of t he real occurs through the action of the franle. And in

both , each in its own way, the frame is experi enced as figurative, as redraw

ing the elements inside it. These two images by LVIan Ray, the work of a

photographer who participated directly in the movement, are stunni ng

instances of surreal ist visual practice. But others, qualifying equally for th is

position as t he 'g'reatcst' of surreal ist images, a re not r eally by 'surrealists:

BrassaX's I nvoluntary Sculptures or his nudes fo r the journal Minotaure arc

examples. And thi s fact would seem to rai se a problem. }l or how, with th is

blurring of boundaries, can we come to understand surrealist photography?

How can we thi nk of it as an aesthetic category? Do t he photographs t hat

for m a historical cluster, either as objects made by surreal ists or chosen by

ul em, do they in fact const itute some ki nd of unified visual fi eld? And can

we conceive this field as an aesthetjc category?

PART THREE: MODERt'-'ITY A..'-'D PHOTOGRAPHY "7

Plate 14 .:\lan Ray,l\!omunenl to DA.F dJ! Sadc, 1933, gelatin silver print and ink, 2 0 x 16 em.

Israel :'.Iusewn, Jerusalem, counes), of The Vera, Silvia and Arturo Schwarz Collection of

Dada and Surrealist Art. Photo: Ih 'shalom A\"ital. C Man Ray Trust/ ADAGP. Paris and

DACS, London 2003.

"Vhat Breton himself put together, however, in the fi rst Surrealisl 1l1anifesto

was not so much an aesthetic category as it was a focus on certain states of mind

- dreams - certain criteria - the marvel ous - and certain processes - automa

tism. T he exempla of these conditions could be picked up, as though Lhey , ..'ere

trouvailles at a flea market, al most anywhere in history. And so Breton finds the

marvelous' in ' the romantic ruins, the modern mannequin . .. Vill ods gibbets,

Baudelaire's couches.':- And his famous incantatory list of history's surreal ists is

,,8 ART OF THE nVENTlETH CENTURY: A RRADER,

precisely the demonstration of a ' found' aesthetic., rather than one that thinks

itself through the formal coherence of, say. a period style:

Swifl is Surrealist in malice.

Sade is Surrealist in sadism.

Chateaubriand is Surrealist in exoticism.

Constant is Surrealist in politics.

Hugo is Surrealist when he isn' t stupid. 8

Tn the beginning the surrealist movement may have had its members, its

paid-up subscribers, we cOlll d say. but there were many morc complimenlluy

subscr.iptions being sent by Breton to far-off places and into the distant pasl.J.J

T his attitude, which annexed to surrealism such disparate artists as Uccello,

Gustave i\1oreau, Seurat, and Klee, seemed bent on dismantling the vcr)' notioll

of style. One is therefore not surprised at the position the poet and

Pierre took up agrullst the ' Beau.x-Arts' when he limited thc visual aes

thetic of the movement LO memory and the pleasure of the eyes and produced a

list of those things that would produce this pleasure: streets, kiosks, automobiles.

cinema, photographs.

1O

Tn modeling what he intended as the mO\-emenl'S author

itati\-e journal, La Revolillioll surtialiste, after the French scientific re\>1ew La

lYalure, Naville wanted to clarify that this was not an art magazine, and his deci

sion. as its editor, to include a great deal of photography was predicated precisely,

he has said, on the a\'ai lability of photography's inlages - one could fmd them

anywhcre.

1I

FOT l'\aviHe, artistic style was anathema. 'I have no tastes,' he wrote,

'except djstastc_ :vIastcrs, master-crooks, smear your canvases. E\-eryone knows

there is no surrealisl paiming. Neither the marks of a pencil abandoned to th('

accidents of gesturc, nor the image retracing the forms of the dream . . .'U

To place in this way a ban on accident and dream as the basis of a visual

styl e, thereby proscribing the very resources on which Breton depended, was

to make of himself a kind of roadblock in the direction along which surrea l

ism was moving. Naville's struggle with Breton is acted out in the masthead

of La Revolution surrealisle, which is issued at its beginning from .i ts rue de

Grenelle headquarters, dubbed the ICentral e,' its editors listed as Naville and

peret. then is wrested from them in the third issue by Breton and moved to

the rue Fontaine, only to return for one number to the Centrale, until it is

definitively taken back home by Breton to the r ue Fontaine. ;\lany things

were at issue in this struggle, but one of them was painting_ For by the mid

die of '9!25 Breton had allowed the possibility of 'Surrealism and Painting;

in the text he produced by that name. At first he thought of it in terms of

' found' surrealists, like de Chirico or Picasso. But by March 1926 his second

installment of this essay was bent on constructing precisely what 'everyollf'

knows' t here is none of: a pi ctorial ffiO\-ement, a stylistic phenomenon, a sur

real ist painting to go into the newly organized Galerie Surrealiste.

In going about formulating thi s thing, this style, Breton resorted to his very

PART THREE: MODERNITY AND PIiQTOGI\AJlHY

"9

own privileging of \-isuality, when in the first JVlanijeslo he had located his own

invention of psychic automatism within the experience of hypnogogic images

_ that is, of half-waking, half-dreaming visual experience. For it was out of the

priority that he wanted to give to this sensory mode - the very medium of

dream e.'\.-perience - that he thought he could institute a pictorial style.

'Surrealism and Painting' thus begins with a declaration of t he absolute

value of vision above t he other senses_13 Rejecting symboli sm's notion that art

should aspire to the condition of music, Breton rej oins that ' visual images

attain what musi c never can/ and he adds, no doubt for the benefi t of twen

ti eth-cent ury proponents of abstracti on, 'so may ni ght continue to descend

upon the orchestra.' Breton had opened by extolling vision in terms of its

absolute immediacy, its resistance to the ali enating powers of thought. 'T he

eye exists in its savage state,' he had begun. 'T he marvels of the earth __ . have

as their sole witness the wild eye that traces all its colors back to the rainbow.'

Visioll , defined as primitive or natural, is good; it is reason, calculat.i ng, pre

medi tated, controlling, that is bad.

No sooner, however, is the immediacy of vision established as the grounds

for an aesthetic, that it is overthrown by something else, something normally

t hought to be its opposite: wTi ting. Psychic automatism is itseU a \\Titten

form, a 'scribbling on paper,' a textual producti on_Describing the automatic

drawings of Andre i\.Jasson - the painter whose 'chemistry of t he intellect'

Breton was most drawn to - Breton presents them, too, as a kind of writing,

as essentially cursive, scriptorial , the result of 'this hand, enamoured of its

own movement and of that al one.' ' I ndeed,' he adds, ' the essenti al discovery

of surrealism is that, without preconceived intention, the pen that flows in

order to wTite and the pencil that runs in or der to draw spin an infinitely pre

cious substance.' So preferabl e is this substance, in Breton's eyes, to the fun

damentally visual product of the dream, that Breton ends by giving way to a

distaste for the ' other road available to Surrealism,' namely, 'the stablizing of

dream images in the kind of still -life deception known as trompe l'oeil (and

t he very word " deception" betrays the weakness of the process).'

Now this disti nction between writi ng and yision is one of the many

omies that Breton speaks of wanting surrealism to dissolve in the hi gher syn

thesis of a surreality that will, in this case, 'resolve the dualism of perception

and representation."4 It is an old opposition within \\Testern culture and one

that does not simply hold these two modalities to be contrasting forms of

experience, but places one higher than the other.

15

Perception is better - tTuer

_ because it is imlnediate to experience, while r epresentation must ahvays

remain suspect because it is nevcr anythi ng but a copy, a re-cr eation in anoth

er form, a set of signs for experience. Because of its distance from the real,

representati on can thus be suspected of fTaud.

In preferring the products of a cursive automatism to those of d.ream imagery,

Breton appears to be reversing the classical prefe:rence of vision to writing. For in

120 ART OF THE nVENTtETH CENTURY: A READER

Breton's definition, it is the pictorial image that is suspect, a ' deception/ while the

cursive one is true,16

Yet this reversal only appears to overthrow the traditional Platonic dislike of

representation. In facr., because the visual imagery Breton suspects is a picture.

and thus the representation of a dream rather than the dream itself, Breton here

continues "" estern culture's fear of representation as an invitation to deceit. And

the truth of the CUTS1\'C flow of automatist wri ting or drawing deri\'cs precisely

from the faeL that this activity is less a representation of something than it is a

manifestation or recording: like tlle lines traced on paper by machines that mon

itor heartbeats. vVhat this cursive web makes present by making visible is a direct

connection to buried miues of experjcnce. 'Automatism,' Breton declares, ' leads us

in a straight line to this region,' and t he region he had in mind is obviously the

lUlconscious.17 VVi th this directness, automatism makes the unconsci ous present.

Automatism may be wri ting, but it is not representation. It is ilnmediate to expe

rience, untainted by the distance and extenority of signs.

But this commitment to automatism and writing as a special modality of

presence, and a consequent dislike of representation as a cheat, is not consis

tent in Breton. As we will see, Breton expressed a great enthusiasm for signs

- and thus for representation - since representation is t he very core of his def

inition of Convulsi\'e Beauty, and Convulsive Beauty is another term for the

Man'elous: the great talismanic concept at the heart of surrealism itself.

On the levcl of theory, these contradictions about the priorities of vision and

representation, presence and sign , perform what the contradiction between the

two poles of surreal ist art Inanjfests on the level of forlll. For the problem of how

to forge some kind of stylistical ly coberent entity out of the apparent opposition

between the abstract liquefaction of :\liro's art, on the one hand, and the dry

realism of Magritte or Dah, 0 11 the other, has continued to plague every writer

- beginning with Breton himself - who has set out to defi ne sWTealist art-Is

Automatism and dream may seem coherent as parallel functi ons of unconscious

activity. but give rise to image types that seem irreconcil ably diverse.

It is wi thin this confusion o,'cr t he nature of surrealist art that t he present

investigation of surrealist photography should be placed. }-lor to begin that

investigation with t he claim that surrealist photography is the great

unknown, undervalued aspect of surrea1i st practice, but that nonetheless, it is

the great production of the mo\ement, is undoubtedly to write a kind of

promissory note. l\1.ight Dot this 'work be the very key to t he dilem_ma of sur

reali st style, the catalyst for the sol ution, the magnet that attracts and there

by organizes the particles in the field?

On t he surface of things, t his woul d seem a promise impossible to keep.

The very same diversity, so troubling to the art histori an or cri tic who tries to

think coherence into the contradictory condition of surrealist pictorial pro

duction, repealS itself wi thin the corpus of the photographs. T he r ange of sty

listic options taken by the photographers is enormous. There are ' straight'

PART THREE: MODERNITY Al.'(D PHOTOGRAPHY 12 1

Plate 15 Jacques-Andre Boi ffard , The Big Toe, 1C)1. 9, photograph from Georges Bataille 'I.e

gros oneil' in Documents, ,\ 0 6, 1929. Centre Pompidou-1\ I,\ \ :7\l-CCl , Pans. Photo; C

D1SL R.\lX

Plate 16 Raoul Ubac., II omaIl / Ciomi (La 1939. Centre Pompidou-!\1J. \lA \i -Cel,

Paris. DisL 0 AD AGP, Par is and DACS. London 2003.

images, sharply focused and in close-up, which vary from t he contemporane

ous production of Neue Sachlichkeit or Bauhaus photography only in the

peculiarity of their subjects - like Boiffard's untitled photographs of big toes,

[Plate ISJ or Dora Maar's Ubu (1936), or Man Ray's hands, or Mescns' As f Ve

Understand It (Comme nous l'entendolls .. ,) ; - but sometimes, as in the

images Brassal made for L 'Amour fou, not even in that. There are photographs

that are not 'straight' but are the result of combination printing, a darkroom

maneu\'er that produces the irrational space of what could be taken to be the

image of dreams. Some of these retain the crispness and defi nition of any

contemporary Magritte or Dati; others, particularly t hose by Ubact begin to

slide into the fluid, melting condition that we associate more with the picto

rial terms elaborated by Masson and Miro [Plate 16]. And there 'were of

course techniques associated directly with automatist procedures and the

courting of chance. Thus Ubac speaks of releasing photography from the

rationalist arrogance' that powered its discovery and identifying it with \he

poetic movement of liberation' through 'a process identical with that of

aUlomatism.'19 Ubac's brulages, photographs in which the image is modified

by melting t he negative emulsion before printing, arc thought to be one

exampl e of t his;:lO Man Ray's rayographs - cameraless ' photograms' produced

12

3

122 ART OF THE nVE,...nlETH CE..''1T\':RY: A READER

/ / .

{ (''Uviu'tL

l! ('

Plate 17 Breton, Sc!f-Portrait: L'&riture AUlOl1lnllque, 1938, photomontage, 1+2 x 19 em.

The Vera, Silvia and Arturo Schwan. Collection of Dada and Surrealist Art at the Jsracl

Museum, JerusaJem. Photo: Avshalom A\' itaJ Q ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2003.

by placing objects directly on photographic paper. which is then exposed to

light - can be seen as another. As Ma n Rav himself said by Irecal ling t he

event more or less clearly, like the undistUIbed ashes of an object consumed

by flames,' the rayographs seemed like those precipitates from the uncon

scious on which automat ist poetic practice was founded.

2 1

The technical diver

sity of photographic surrealism does not end here. ' Ve must add solarization,

negative printing, cliche verret multiple exposure, photomontage, and photo

collage, noting that wi thin each of these technical categories there is the pos-

P\RT THREE: MODERI'ITY A.'\jD PHOTOGRAPln

sibiLity of the same stylistic bifurcation (linear/ painterly or representational!

abstract) that surrealist painting exhibits.

Kowhere does this internal contradiction seem more immediately available

than in the photo collage that Andre Breton made as a self-portrait, a work

called L'Ecrit.ure aUlomalique [ Plate I :-J. For here in a single work is enshrined

the very split for which these stylist ic terms are the surrogates: vision/ writing.

Breton portrays hiJDself with a microscope, an optical instrument invented to

expand normal eyesight, to c",:tend its powers in ways not unlike those associ

ated with the camera itself. I Te is shown, that is to say. as the surrealist seer,

armed with vision. But th is condition of '.;siol1 produces images, and these

images are understood as a textual product, hence t.he title Automalic rf/riliflg.

There is, however, one important factor that must be added to any considera

tion of Breton's Automalic Wn:liflg before concluding that its contradictions are

irreconcilable. It is a factor that allows one to think, as Breton seems to have been

doing here, about the relationship between phowgraphy and writing. t\ormally

we consider wTiting as absolutely banned fTom the photographic field. exilC'd by

the \'ery nature of the image - the 'message \\;thout a code' - to an c\.tcrnal

location where language fWlcLions as the ncccssary interpreter of the rnuteness

of the photographic si gn.

u

This place is the caption, the very necessity of which

produced the despair that Brecht, for example, felt about photography. Walter

Benjamin cites this hostilit)f to the 'stTaight' photograph when he quotes 'Brecht's

objection to the camera image: I}\ phowgraph of the Krupp works or GRe yield.s

almost nothing about these institutions .... Therefore something has actively w

be construcled, something artificial, somethi ng set-up.'J.3 Throughout the avant

garde of the 1920S and 1930 5 that somethi ng, that constructed photograph, was

the photomontage, about which it could be claimed that it 'expresses not simply

the fact \vruch it shows, but also the sociallendency expressed by the fact.':q And

this notion of the montage's insistence upon meaning, on a sense of reali ty bear

ing its OWI1 interpretation, was articulated by Aragon's reception of the '....ork of

the revolutionary artist John I Teartfield: ',\ s he was playing with the Ere of

appearance, real ity took fire around him .... 'The scraps of photographs that be

formerly manoeu'.Tcd for the pleaslue of stupefaction, lUlder his fingers begin to

signify,' The possibility of signification that AIagon saw in Hearlfleld seems to

have been llnderstood as a function of the agglomerative, constructed medium

of photo collage. Referring in another context to the separate collage elements

of Ernst's montages, Aragon compared them to ' words.'l:;

In what sense, we mi ght ask, could t.he very act of collage/ montage be

thought of as tex1.ual- as it seenlS to ha'.'e been so thought by these writers? And

is this a logic that can resolve what is contradictory in L'&n:lure automatique?

Objects metamorphosed before my very 9'l!Sj they did not assume WI allegan'cal SIlUlce or

tire personality of .fymboLs; they seemed Less lhe outgrowths 0/ all idea tilallthe idea itself.

- Louis Aragon:26

12

4

ART OF THE nVE......'T1ETH CENTURY: It. RI::ADI-: R

If these works were able to 'signify,' to articulate reality through a kind of

language, this was a function of the cell ular structure that montage exploits,

with its emphatic gaps between one shard of reality and another, gaps that in

the montages fTom the early 1920 S by the dadaists Hannah Hoch or Raoul

Hausmann left rivers of white paper to fl ow around t he individual photo

graphic units. For this cell constr uction mimi cs not the look of words but the

fo r mal preconditions of signs: the fact that they require a fundamental exte

riority between one another. I n language t his exteriority man ifests itself as

syntax, and syntax in tur n is both a system of connection between the ele

ments of a language, and a system of separat ion, of mai ntai ni ng the differ

ence bet ween one sign and t he next, of creating meaning t hrough the syn

tacti cal condition of spacing.

By leaving the blanks or gaps or spaces of the page to show, dada montage

traded in the powerful resource of photographic realism for t he quali ty that

we coul d call the 'language effece' Normally, photography is as far as possible

from creating such an effect. For photography, with its technical basis in an

instantaneous recording of an event, captures what we coul d call the si mul

taneity of real space, t he fact that space does not present itself to us as suc

cessi\'e in nature, like time, but as pure presence. present-all-at-once. By car

rying on its continuous surface the trace or imprint of all that vision captures

in one glance, photography nor mally functions as a kind of declaration of t he

seamlessness of reality itself. It is this seamlessness that dada photo collage

disr upts in an attempt to in fil trate reali ty with interpretati on, w'ith significa

tion, wi th the very wTiting to which Breton refers in his own collage: ecriwre

automatique. It is this seamlessness of the photographic field t hat is fractu red

and segmented in DaIi's extraordinary collage The Phenomenon if

(Le Phenometze de I 'extase) [Plate 18]i as well , and with the similar produc

tion of the language effect. For, within the grid that organ izes the ecstatic

images of women, we fi nd the incl usion of stri ps of different ears, taken from

t he catalogue of anatomical parts assembled by master police chief Alphonse

Berti llon that stands as ule nineteenth-century criminological attcmpt to li se

photography to constTuct the 'porlrait parlanl,' or speaking likeness, wiuless to

the last century's expectati on that, like other 'mediums,' photography could

WTest a message from the muteness of material reality.

If photo collage set up a relationshi p between photography and 'languagc,'

it did so at the sacrifice of photography's priv'ileged connection to the world.

T his is why the surrealist photographeTs, for t he most part, shunned t he col

lage technique, seeming to have found in it a too-willing surrender of pho

tography's hold on the real. Darkroom processes like combination printing

and double exposure were preferred to scissors and paste. For these techni ques

could preserve the seamless sur face of the final print and t hus reenforce the

sense that this image, bei ng a photograph, documents the reality from which

it is a transfer. But, at the same ti me, this image, internally ri ven by the effects

PART THREE: YIODER?-TIT AND P'-JOTQGRAPHY

12

5

Plale 18 Salvador DaH, The Phenomeflon of &Slasy, photomontage from Nos.

3- +, '4 December 1953 Courtesy of The British I.ibrary, London. BL cISo.d. 1. 0 Salvador

Dali, Gala - Salvador Dali Foundations/ OAGS, London 2003.

126 ART OF THE TIVE..r."\TlETH CEI\'TUR'i: A READER

of syntax - of spacing - would imply nonetheless that it is reality that has

composed itself as a sign.

To cOlwulse reality from within. to demonstrate it as fTactured by spacing.

became the coUectl\'C result of all that vast range of techniques to which SUT

realist photographers resorted and which they understood as producing the

characteristics of the sign. For example, solarization - in which photographic

paper is briefly exposed to light during the priJlting process, thereby altering

in varying degrees the relationship of dark and light tones, introducing ele

ments of the photographic ncgtati\"c into the positive print - creates il strange'

effect of cloisonne, which visually walls off parts of a single space or a whole

body frolll one another, establishing in this way a kind of testimony to a clovcn

reality. Negative printing, which produces an entirely negative print, with the

momentarily unintelligible gaps that it creates within objeclS} promotes th"

same effect. But nothing creates this sense of the linguistic hold on the rcal

more than the photographic strategy of doubling. For it is doubling that pro

duces the formal rhythm of spacing - the twostep that banishes sinlultaneity.

And it is doubling that elicits the notion that to an original has been added its

copy. The double is the simulacrwn, the second, the representali\re of the orig

inal. It comes after the first, and in this following it can only exist as figure, or

image. But in being seen in conjunction with the original, the double destroys

the pure singularity of the first. Through duplication, it opens the original to

the effect of difference, of deferral. of one u.lingafter-another.

This sense of opening reality to deferral is one form of spacing. But dou

bling does something else besides transmute presence into successi on. It also

marks the first in the chain as a signifying element- which is to say, doubl ing

transforms raw matter into the conventional shape of the signifier.

Linguistics describes this effect of doubling in terms of an infant"s progress

from babbling to speech. For babbling produces phonemic elements as mere

noise as opposed. to what happens when one phoneme is doubled by another.

Papa is a word rather than only a random repetition of the sound pa because

'The reduplication indicates intent on the part of the speaker; it endows th"

second syllable with a function different from that which would have been

performed by the flrst separately, or in the form of a potentially Ijmitlcss

series of identical sounds / papapapa/ produced by mere babbling. Therefore

the second / pa/ is not a repetition of the fITst, nor has it the same significa

tion. It is a sign that, like itself, the first / pa/ too was a sign, and t hat as a pair

they fall into the category of signifiers, not of things signified.':!;

Repetition is thus the indjcator that the wild sounds of babbling have been

rendered deliberate, intentional , and that what they intend is meaning.

Doubling is in this sense the 'signjfier of signification.'

\Yithin surrealist photography, doubling also functions as the signifier of

signification. It is this semiological, rather than stylistic, condition that unites

the vast array of the movement's photographic production. As we observe t he

p\RT THREE: MODE.RXITY "1l0TQGRAPIlY 12;

Plate 19 l-lam Bellmer,

Doll, 1936'49, silvcrprint

coloured with aniline, 41

:\ 32.9 Cffi. Centre

Pompidou. i\INA':\I-CCJ,

Paris. ., Photo:

DisL

R:,\L"I. 0 ADAGP, Paris

and DACS, London 2003.

various technical opti ons explored by surrealist photography, moving from

unmanipulated straight photography, to negative printing, to solarization, to

montage, to rayography} ulere is the constant preoccupation with doubling.

\Ye come to realize that this is not only a thematic concern. it is a structural

one. For the structure of the double produccs t he mark of the sign.

vVe find this withil1Hans Bellmer's Dolls (Poupees, 1936), where the

mechanically duplicated parts of a doll's anatomy ailo\'.- for a doubling of

these doubles and the doll herself call be composed of identical pairs of legs

mirroring each other [Plate 19]. T his can happen within the very construction

of the doU, or from the do1l's momentary arrangement for a gi\-en photo ses

sion, or through paired prints of near-twin images. All of these are rendered

through techniques of documentary photography in which manipulation is

studiously avoided. But at other points in Bellmer's production} the doubling

can manjfest itself technically within the image, as in the double e),"posures

that multiply the multiples. Double exposure functions in ]\!an Ray's work to

produce, for example, the famous doubling of the eyes of the Afarquise

Cassali. That photographs, multiple by nature, can themselves be doubled

makes furth er doublill g available, as in the SLacking of images. Man Ray's col

lage of doubled breasLS in the opening number of La R evolution surrealisle

(1924) serves as one example, or, again, Frederick Sommer's similarly doubled

landscapes reproduced in the American surreali st journal VVV(1944), or Man

Ray's doubles in rayographi c form, as the mass-produced, multiple object of

the phonograph record (manufactured of translucent plastic in the days when

this work was made) is paired and tJlereby twinned. The Dislorlions, which

.28 . 29 OF THE TWEXTlETH CENTURY: A READER

Plate 20 Man Ray, SLipper- spoon, 19yh photograph. Courtesy of Telimage

2003. C i\.Jan Ray Trust. ADAGp, Paris and DAGS, London 2003

Andre Kertesz made in J933, e':\''P)oit the doubling of the mirror to create a

series dedicated to this effect.

As we noted beforc, surrealist photography e.xploits the very special con

neclion to realjty with which all photography is endowed. Photography is an

imprint or transfer of the real: it is a photochemically processed trace causal

ly connected to that thing in the world to wh.ieh it refers in a way parallel to

that of fingerprints or footprints or the rings of water that cold glasses

on tables. The photograph is thus genetically distinct from painting or sculp

ture or drawi ng. On the frunily tree of ilnages it is closer to palm prints, deat h

masks, cast shadows, the Shroud of Turin, or the tracks of gull s on beaches.

Technically and semiologically speaking, drawing and paintings arc icons,

while photographs are

Given photography's special status with regard to the real - that is, bei.ng a

ki nd of deposit of the real itself - the mani pulations wrought by the surreal ist

photographers, the spacings and doublillgs, are intended to register the spacings

and doublings of that very reality of which this photograph is merely the faith

ful trace. In this way the photographic medium is exploi ted to produce a para

dox: the paradox of reality constituted as a si gn - or presence transformed into

absence, into representation, into spaci ng, into writing. ill this semiological

move surrealist photography parallels a similar move of Breton's. For Bretoll.

though he promoted as surrealist a vast heterogeneity of pictorial styles, devised

a defmition of beauty that is rather more unified and that is itself translatable

il1to semiological terms. Beauty, he said, should be convulsive.

I n explaining the nature of that convulsion in me text t hat serves as prologue

to L'Amowjou, Breton spells out the process of reality contorting or convulsing

itself into its apparent opposite, namely, a sign.29 Reality, which is present.

becomes a sign for ",..hat is absent, so t hat the world itself, rendered beautiful, is

understood as a 'forest of signs. ' In defining what he means by thi s 'indice,' this

PART THREE: MODERNITY AND PHOTOGRAPHY

sign. Breton begins to sketch a theory not of painting, but of photography.

Each of Breton's aspects or moments of convulsive beaut)' are ways of

describing the action of signs. The first - 'erolique-voiLee' - in\'okes the occur

rence in nature of representation. as one animal imitates another or as inor

ganic matter shapes itself to look like statuary. T he second, termed

ezplosanle-fixe,' is related to the lexpi ration of movement.' which is to say the

experience of something that should be in motion but has been, for some rea

son, Slopped, derailed, or as Duchanlp would have said, :delayed. ' In this

regard Breton writes, 'I am sorry not to be able to reproduce, among the illus

trations to this text, a photograph of a very handsome locomotive after it had

been abandoned for many years to the delirium of a virgin forest.'3

0

The con

vulsiveness, then, the arousal in front of the object is not to it perceived wi t h

in the continuum of its natural exi stence, but detached from that flow by

means of an expiration of motion, a detachment that deprives the locomoti ve

of some part of its physica l self and turns it into a sign of the reality it no

longer possesses.

Breton's third example of convulsive beauty - 'magique-circonslancielle'

consists of the found object or found \'erbal fragment, both instances of objec

tive chance, where (specifically in the case of the fowld object) an emissary

from the external world carries a message informing the recipient of his own

desire. The found object is a sign of that desire, Breton recognized this kind

of convu.lsive beauty in a slipper spoon he had found in a flea market, an

object he recognized as the fulfil1ment of a ,-..rish spoken by the automatic

phrase that had begun running through his mind some months before [Plate

20]. The phrase, cendriller-Cendrilloll, translates as 'Cinderell a ashtray.' The

flea-market obj ect - a spoon with a li ttle shoe affu.:ed to the underside of its

handle - suddenly convulsed itself into a sign when Breton began to see it as

a chain of representations in whi ch the 'shoe' was reduplicated to infinity, as

though caught in a hall of mirrors. I n addition to the little shoe under the

handle, he suddenly saw the bowl and handle of the spoon as t he front and

last of another shoe, of which the little carved slipper was only the heel. Then

he imagined thal slipper as having for its heel yet another sli pper and so on to

infinity. This chain of redupli cated and mirrored slippers Breton read as a

kind of natural writing, a set of lindices' that signi fi ed his own desire for love

and the beginning of a quest whose magical unfolding is plotted throughout

L'Amow-jou.

If we are to generalize the aesthetic of surrealism, the concept of

sive beauty is at the core of its aesthetic, a concept that reduces to an experi

ence of r eality transformed into representation. Surreality is, we could say,

nature convulsed into a kind of writing. The special access that photography,

as a medium, has to this experience is photography's privileged connection to

the r eaL The manipulations t hen available t o photography - what we have

been calling doubling and spacing as weB as a technique of representational

151

ART OF TWE:-:TIErH CE.....'Tl..'R'f: 1\ READER

13

reduplicatioll, or sUucture en abyme- appear to document these connllsions.

The photographs are not inlerpretalions of reality, decoding it as in the

phogomontage practice of Heartfield or Hausmann. Instead, they are presen

lations of that very reality as configured or coded or \vritten.

The experience of nature as sign or representation comes naturally, then, to

photography. This experience extends as well to the domain that is most

inherently photographic: the framing edge of the image experienced as cut or

cropped. This is possible even when the image does not seem folded from

within by means of the reduplicative strategy of doubling, when t he image is

entirely unmanipulated, like the Boiffard big toes, or the I nvoluntary

Sculptures by BrassaY, or the image of a hatted figure by Man Ray publi shed

in J\rJillotaure5

'

For, at the very boundary of the image, the camcra frame,

which essentially crops or cuts the represented element out of reality at large,

can be seen as another example of spacing.

Spacing. like the doubled phonemes of papa, is the signifier of significa

tion, the indication of a break in t he simultaneous experience of t he real, a

rupture that issues into sequence. P hotogr aphic cropping is always experi

enced as a ruptUIe in the continuous fabric of reality. But surreal ist photog

raphy put.s enormous pressure on that frame to make it itself read as a sign

- an empty sign, it is true, but an integer in the calculus of meaning

nonetheless, a signifier of signification. T he frame announces that, between

the part of real ity cut away and thi s part, there is a difference; and that this

segment , which the frame fra.mes, is an example of nature-as-representa

t ion or E\"en as it announces th is experience of reality, the

camera frame, of course, controls it, configures it.3'l This it does by point of

view, as in t he :\1an I\ ay. or focal length, as in the extreme close-ups of

Brassai". But in both these instances what the camera frames, and thereby

makes visible, is the automatic writing of the world: the constant, uninter

rupted production of signs. BrassaI's images are of those nasty pieces of

paper, like bus tickets and t heater-ticket stubs that we roll into li ttle

columns in our pockets or those pi eces of eraser that we unconsciously

knead - these are what his camera produces through the enlargements that

he published as im"oluntary sculptures. 1\1an Ray's phot ograph is one of sev

eral made to accompany an essay by dada's founding spirit, Tristan Tzara,

about the constant unconscious production of sexual imagery throughout

culture - here, in the design of hats.

The fr run e announces t he camera's ability to fmd and isolate what we could

call the world's constant production of erotic symbols, its ceaseless automatic

wTiLing. In this capacity the frame can itself be glorifi ed, not iced, represent

ed, as in the Ni rul Ray monwnent to the Marquis de Sade. Or it can be t here

silently, operating as spacing, as in BrassaY's seizUIe of automatic production

through his images of sculptural onanism or hi s captUTed grafitti.

I n cutting into the body of the world, stopping it, fram.ing it, spacing it.

I'.-\.I\T THREE: MODER.."rrv A..."D PHOTOGRAPHY

photography reveals that world as written. Surrealist vision and photograph

ic vision cohere around these principles. For in the explosallle-fLXe we

er the stop-motion of the still photograph; in the erolique-voiM we see its

framing; and in the magique-circollslallcielie we find the message of its spac

ing. Breton has thus provided us all the aesthetic theory we will e ....er need to

understand that, for sUIrea.list photography, too, 'beauty will be convulsi\'c or

it will not be.'

Andre Breton, \/am/e5loJ of Sur,.eubsm, trans. Richard Seaver and I ld>n R. Lane (Ann \rOOr: "!l,e

U'niversity of \ Jichigan 1969), p. 12.

Andre Breton, 'Le Surrcalisll1c N 1ft peimurc: La Ret'Olullon surrialiste, no. 4 1911) , p. 18 The

compl>t> senes of dSaya was rollectoo in Ilr>ton, Surrralism and Pmmin&. tran", SlIlIon \\alSOll

Taylor (New York..: I l arpt'r & Ro...., '9:-:l). runher ref>r>llce5 arc to this translation.

j Breton, .lIonifes.tos, p. i.

"" Andre Brelon, Yad/a. trans.. Richard Iloward (.\'ew York.: Press, 1960). p. In the preratt to

the 1963 Prellch edition (Galhmard), Breton speau of the photographs in relation to one of the

'antihterary' principles that guided Lhe creation of the book. 'The abundant photographIc illuslfa'

lion,' he writes, ' had as us obicttl\-e the elimination or all dCSC'ription- what had been chided as iIlane

in the Surrealist j\lanifeslo- and the tone that the adopted was modeled on Lhat of medlca.1

obsen.(ltioll .. .' See- Beaujour. 'Quest-ce que "),adja"T La Youvdle Rn'ue FrunfoiM, no. 1;1

(April I , 196;), pp. :-80"-99, ror an analYSIS of \adla's rondllion as a ' text ' that is open 10 addlUons

from what would nonnall) be \ ie-wed as hors-le.rte and the role the photographs pin' in Lhis "gard.

:; This question had begun. 'The pholographic print . . . 15 permeated with an n.lue Lhal maks

il a supremely preciow .rude or exchange' (SurrralullI and p. Yl).

ti '\ndre Breton, 'La Beautl sera ... ' no. 5 ('934), pp. 9-16. \\'alter BenJamm.

'Surrealism: lbc Last Snapshot of the E.uropean Intelligentsia,' in Reflections., trailS. Edmund

Jephrott (Xew York: Ilarrourt Brace Jovanovi ch. 19:-8), p. 183 See Rosalind Krauss,

-Irt Journal +5 (Spring 1981): n-8.

8rNon. \/onifestos, p. 16.

Ibid., p. 7.7.

I) Iksides the famous 'dictionary' defillltion or surreahsm ('II. Psychic automatism in its pure state. .').

BrelOns first Surrralist 'Ilen,ifnio includes an 'encyclopedia' entry iu which rnc performers of acts of

'absolute surrealism' are listed: .\ragon, Baron, Bo,rfard, Breton, Carrh-e, Cre,,...l, Oelteil, Ibnos,

EJuard, Gerard, Llmbour. i\lalkine. \Ionse, Na\-ille, '\011, Perc\, Plcon, Soupauh.. \itr&c.

10 1>lerre .\",wille, 'Beaw: Aru.' La Rhviflilon. surrialislc, no. 5 (April 19:15), p.

II As told to the author in ron'ersatlon, \lin- ::0, 1985. '\1'1\ 1111'" also said that it was he v.hodt'\'lsed the three

pronged photo ooUage of lhe members BIllie Cenu-alc for Lhe CO\-er of the first issue of LA Rhx>/uJ/on.

surrealisre. See his aCCOllill in Pierre ),1'1\'1111"', U Temps du sllrriaJ (pans: Galilee, 19:7), pp. 99""110.

Il .\"a\'llle, 'Beaw:-Aru; p.

I) The quotations in this and the nen paragraph are from Breton, SlIrrralism and PaUltln8, pp. 68, ;0.

I .\.ndre Breton, ilceanie: reprinted in Breton, La CU ths clwmps (Pans: Saglttaire, '97'}

edition), p. 2;8.

I') Breton bere reenacu the polan:tauon between speech and wnting. presence and representauon, that

Derrida analyzes as the oppos"Iliol1$ Lhat structure Western metaphysics. See Ji\cques Ot-rnda, 0/

tram.. G.C. Spl\-ak ( Balumore: Johru Hopkins L'niversity Press, 19-;-6). The roncepl of

developed there (pp. 65.3) and in ' Freud and the Scene of Writing' (in Jacques Ocrridi\,

IIntmg and Differrllce, trails. Alall Bas.s [Chicago: t.:lli'ersuy of Chicago Press, 1978 ]) II IInportalll

for the discussion tha t follows.

16 Thus BrelOlI insists thai 'any fOflll of cxpression In which automatism does not at least ad'ancc

undercover runs a gra\e risk or 1I10\'ing out of the surrcalist orbit' (Surrealism and PIIUI/if/B, p. 68).

I Ibid., p. 70.

18 Wilham Rubin attempts to ronstruCl an ' ullnnsic difvtlllon oj Surrealist paUltln,l i ll his rssa)

'Toward a Critical Framework,' In/onu" ') (September 1966): 35. But becall!le he rl'pnxluC't'S the

same bipolar or bl\""alent ronceptual SLructure Lhat Bf("ton had established ill '9:15, his defimtlon mir

ART OF THE nVENTl lITH CE.,'I'TURY: A READ ER

' 3

2

ron the problems of Breton's iUi well.

Ig See Gamille BI)'ell and Raoul :'.lichelet. /lcluatwn poitlqUL ( 1955; reprinted 1I1 .\lsteel \larien.

L'AclI.nlii surrlolisu [Brussels: Lebeer llossmano, 1979J. pp. 26g--;'O).

20 Chac describes the procedure of also callMi u a S)'5'tem of placing the glass plate

of an e.,.posed negau\'e over a heated pan of water ill order to melt the emulsion; ,It was thw a n

automausrn of destruction, a complete dissolution of the image towards an absolute formlessness. I

treated a large number of my ncgau\"e$ in this manner - the result bt-ing for the most pan disap_

pointing, except in one caM! where a woman in a bathing SUit was trarufonned IIItO 8 thunderstruck

Goddess - a photo titled "La Xebuleuse. '" On an unpublished letter to \ \ 'e!I Ge\-.en from R.aoul

t:bac, dated Dieudonne, 2 1 March, 1981.) . . .

21 )'Ian Ray, Exhibition 1921- 1928 (Stuttgart.: L G. A., 1963)'

:12 ' l\l essage without a code' is Barthes's term in his essays "nle Photographic Message' and ' IUletoric of

the Image,' See Roland Barthes, Image, 1IllS1c, Tu:l, trans. Stephen Ileath (;';ew York: I 1111 and Wang,

19n)

23 In Walter Iknjamill, 'A Short Ihstory or Photography: trans. Stanley \I itchcll. Screen 1J (Spnng

19(2): '24

'24 John Heartfield, the \ 'azl York: Uni\-erse Book!, 19/i), p. 16.

25 Louis Aragon, 'Joh n' I('artfield ella beaute re\'Olullonnaire' (1935), T<,primed in Aragon, u s

( Paris: I lermallll, ' 965), pp. i8--;9.

'l6 \ '18hllL'lI/ku ( Le Paysan de Pans), trans. Frederick Brown ( E.nglewood Clirrs, :-'c" Jcrsey: Prentice

llal!, '9iO), p. 9....

'27 Claude 1.i:' I Strauss, The RQU.'(lIU/ the Cooked, trails, J. and D. \\'cighlm8n (l\ew York: Ilarper& 1\0 \\ .

19-;'0), pp. 359-40.

28 Photography's posItion u 8n index was fi m established by C. S. I)circe wi thin the taxonomy or signs

that he developed In 'Logic as Semiotic: The Theory or Sigm,' C.s. Peirce, PhllosophlcalWnlmgr of

Pevec, ed. Justw Buchler (:-lew York: Dover, 1955).

29 'Ine text ' La beaute sera colwulsl\'e' (pp. cil.) became the first chapter or C1mourfou.. See Andre

Breton, L 'Amour fou (Paris: Gallimard, 1957), pp. :-' 9,

30 Ibid., P. 13.

50' Boiffard's big toes accompanied the text by Georges ' Le Gros Ort('il: Docunumts, no. 6 ( '929);

Brassais Sculpwres I Im:ollln(aves appeared 111 .lflnO/oure, !los. 3-'" ( 195.3), p. 68; Mall Ray's photo.

graphs or hats illustrated Tristan Tzara's ' D'UJl Cenain Automallsme du gout,' J\!inotoun, nos.. 5-4

(1933), pp. 81- 8 ....

.}'2 Derrida analyres the frame as 'an outside which is called inside the inside to col1sut\l(e it as inside.'

See Jacques Dcrrida, "rhe Parcrgon: trans. Craig Owens, OciOMr, no. 9 (Summer 19;'9)'

4. John Szarkowski , from The Photographer's Eye

John Szarkowski worked as a photographer before becoming the curator of

photographs at the Museum of Modem Art . New York in 1962. a post that

he held until hi s retirement in 1991. Through a seri es of highly influential

exhi bitions and accompanyi ng catalogues he el aborated a moderni st

account of photography that drew heavily on the idea of vernacul ar form.

Thi s text was originally written as a catalogue essay for the exhi bition The

Photographer's Eye held in 1969 at the Museum of Modern Art . It represents

a key statement of Szarkowski 's approach and cl early lays out the fi ve ele

ments that he held to be central to photography conceived as an art. The

follOWing extracts are taken from John Szarkowski. The Photographer's Eye.

Museum of Modern Art. New York. 1969. unpaginated. [SE]

PART THREE: MODERNITY A..'D PHOTOGRAPHY

' 33

Introduction

This book is an investigation of what photographs look like, and or why they

look that way. It is concerned with photographic style and with photographic tra

dition: wi th the sense of possibi.lities that a photographer today takes to his work.

The invention of photography provided a radically new pi cture-making

process - a process based not on synthesi s but on selection. T he difference was

a baSIC one. Paintings were made - constructed from a storehouse of tradi

ti onal schemes and skills and attitudes - but photographs, as the man on the

street put it, were taken.

The di ffeTence raised a creative issue of a new order: how could this

mechani cal and mindl ess process be made to produce pictures meaningful in

human terms - pi ctures with clarity and coherence and a point of view? It

was soon demonstrated that an answer would not be fOW1 d by those who loved

too much the old forms, for in large part the photographer was berert or the

old artistic traditions. Speaking or photography Baudelaire said: 'This indus

try, by invading the territories of art , has become ares most mortal e nemy."

And in his own ter ms of re rerence Baudelaire was haIr right; certainly t he

new medium could not satisfy old standards. The photographer must fi nd

new ways to make his meaning clear.

These new ways might be found by men who could abandon their alle

giance to tradi t ional pictori al standards - or by the artistically ignorant, who

had no old all egiances to break. There ha\re been many of t he latter sort.

Since its earliest days, photography has been pr acticed by thousands who

shared no common traditi on or training, who were disci plined and united by

no academy or gui ld, who considered their medium variously as a science, an

art, a t rade, or an entertainment, and who were often una\vare of each other's

work. Those who invented photography were scientists and painters, but its

professional practitioners were a \"ery different lot. [ . .. J

The enor mous popularity of the new medium produced proressi onals by

the thousands - converted silversmiths, t inkers, druggists, black.smiths and

printers. If photography was a new artistic problem, such men had the advan

tage of having nothing to unl earn. Among them they produced a fl ood of

images. In 1853 the ..VellJ- York Daily Tribune estimated that three million

daguerreotypes were bei ng produced that year.'l Some of these pictures were

the product of knowledge and skill and sensibility and invention; many were

t he product of accident, improvisati on, misunderstanding, and empirical

experiment. But whether produced by art or by luck) each picture was part of

a massive assault on our t raditional habits of seei ng.

By the latter decades of the nineteenth century the professionals and t he

serious amateurs were joined by an even larger host of casual snap-shooters. By

the early eighties the dry plate, which could be purchased rcady-to-use, had

replaced t he refractory and messy wet plate process, whi ch dernanded that the

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Photography and Cinema (2008) David CampanyDocument161 pagesPhotography and Cinema (2008) David CampanyMaria Burachu100% (1)

- 25 Boudoir Looks v1Document58 pages25 Boudoir Looks v1Patrick100% (2)

- 38 Lessons Todd Hido Has Taught Me About PhotographyDocument60 pages38 Lessons Todd Hido Has Taught Me About PhotographyMóni ViláPas encore d'évaluation

- Zeiss Ikon Contaflex BookDocument24 pagesZeiss Ikon Contaflex BookAnonymous Pr8IgKePas encore d'évaluation

- Film - A Very Short Introduction (PDFDrive)Document350 pagesFilm - A Very Short Introduction (PDFDrive)Jonathan GoldsmithPas encore d'évaluation

- Antoine D'Agata - Until The World No Longer Exists PDFDocument21 pagesAntoine D'Agata - Until The World No Longer Exists PDFCarissa PobrePas encore d'évaluation

- Eisenman EssayDocument5 pagesEisenman EssayKenneth HeynePas encore d'évaluation

- Documentary Photography: Capturing Truth and Raising AwarenessDocument18 pagesDocumentary Photography: Capturing Truth and Raising AwarenessagharizwanaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Tone Reproduction Ed 2Document7 pagesTone Reproduction Ed 2Evgeniy KorolPas encore d'évaluation

- Double Exposures. Performance As Photography, Photography As Performance - Manuel Vason - 1783204095Document205 pagesDouble Exposures. Performance As Photography, Photography As Performance - Manuel Vason - 1783204095pussywalkerPas encore d'évaluation

- Saul Leiter, Martin Harrison - Saul Leiter - Early Colour-Steidl (2013)Document168 pagesSaul Leiter, Martin Harrison - Saul Leiter - Early Colour-Steidl (2013)mustachificationPas encore d'évaluation

- Film 1900: Technology, Perception, CultureD'EverandFilm 1900: Technology, Perception, CultureAnnemone LigensaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Message Behind the Movie—The Reboot: Engaging Film without Disengaging FaithD'EverandThe Message Behind the Movie—The Reboot: Engaging Film without Disengaging FaithPas encore d'évaluation

- Matthew S Witkovsky The Unfixed PhotographyDocument13 pagesMatthew S Witkovsky The Unfixed PhotographyCarlos Henrique Siqueira100% (1)

- A Personal View Photography in The Collection of Paul F. Walter PDFDocument145 pagesA Personal View Photography in The Collection of Paul F. Walter PDFGEORGE THE GREEKPas encore d'évaluation

- Kodak Essential Reference GuideDocument216 pagesKodak Essential Reference GuideTheWolfGmorkPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading List PhotographyDocument4 pagesReading List Photographyapi-478567704Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ertész: Vintage Galéria BudapestDocument35 pagesErtész: Vintage Galéria BudapestJose Artur MacedoPas encore d'évaluation

- Photography and Cinematic Surface: EssayDocument5 pagesPhotography and Cinematic Surface: EssayVinit GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Photography Theory: A Bluffer's GuideDocument9 pagesPhotography Theory: A Bluffer's Guidexmanws8421Pas encore d'évaluation

- Semiotics and Western Painting: An Economy of SignsDocument4 pagesSemiotics and Western Painting: An Economy of SignsKavya KashyapPas encore d'évaluation

- Photography Is IllusionDocument21 pagesPhotography Is IllusiontrademarcPas encore d'évaluation

- Compare and Contrast Contemporary and Historical PhotographersDocument3 pagesCompare and Contrast Contemporary and Historical PhotographersmsuthsPas encore d'évaluation

- Photography and Time - Decoding The Decisive MomentDocument24 pagesPhotography and Time - Decoding The Decisive MomentRichCutlerPas encore d'évaluation

- Joan Fontcuberta Post Photography and THDocument22 pagesJoan Fontcuberta Post Photography and THSofia BerberanPas encore d'évaluation

- 2005 SummerDocument36 pages2005 SummerzencubiPas encore d'évaluation

- Portraits in Painting and PhotographyDocument16 pagesPortraits in Painting and PhotographyBKPhdPas encore d'évaluation

- Theoriesof Photography PDFDocument36 pagesTheoriesof Photography PDFJuvylene AndalPas encore d'évaluation

- The Night Albums: Visibility and the Ephemeral PhotographD'EverandThe Night Albums: Visibility and the Ephemeral PhotographPas encore d'évaluation

- Camera NotesDocument1 662 pagesCamera NotesAndrei PoseaPas encore d'évaluation

- Thinking and Not Thinking PhotographyDocument7 pagesThinking and Not Thinking Photographygeet666Pas encore d'évaluation

- JEFF WALL Frames of ReferenceDocument11 pagesJEFF WALL Frames of ReferenceEsteban PulidoPas encore d'évaluation

- Lucy Smith Julia Margaret Cameron and Archival Creativity PDFDocument258 pagesLucy Smith Julia Margaret Cameron and Archival Creativity PDFmalochaPas encore d'évaluation

- AN APOLOGY FOR ARTPHOTOGRAPHYDocument5 pagesAN APOLOGY FOR ARTPHOTOGRAPHYRodrigo PeixotoPas encore d'évaluation

- Portraiture. Facing The Subject PDFDocument48 pagesPortraiture. Facing The Subject PDFErnestina Karystinaiou EythymiatouPas encore d'évaluation

- Matisse and Room 7Document134 pagesMatisse and Room 7Carlo Roa100% (1)

- All Photographers1Document71 pagesAll Photographers1api-244578825Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Photographic Idea Lucy SouterDocument12 pagesThe Photographic Idea Lucy SouterBezdomniiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Book As PerformanceDocument106 pagesThe Book As PerformanceVerónica Stedile LunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Photograms & ScanographyDocument33 pagesPhotograms & ScanographyaborleisPas encore d'évaluation

- A Guide To Collecting PhotographyDocument22 pagesA Guide To Collecting PhotographyrydcocoPas encore d'évaluation

- Fashion Constructed Image TASKSDocument4 pagesFashion Constructed Image TASKSBA (Hons) Photography, Contemporary PracticePas encore d'évaluation

- Art of The Digital Age by Bruce Wands PDFDocument2 pagesArt of The Digital Age by Bruce Wands PDFvstrohmePas encore d'évaluation

- Photography Matters The Helsinki SchoolDocument49 pagesPhotography Matters The Helsinki SchoolDavid Jaramillo KlinkertPas encore d'évaluation

- August Sander Notes PDFDocument6 pagesAugust Sander Notes PDFRodrigo AlcocerPas encore d'évaluation

- Sequential Equivalence Final DraftDocument59 pagesSequential Equivalence Final DraftBrian D. BradyPas encore d'évaluation

- 100 Things PhotographyDocument4 pages100 Things Photographypreethi3Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Sophist An The Photograph Olivier RichonDocument6 pagesThe Sophist An The Photograph Olivier RichonDawnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Focal Press The Darkroom CookbookDocument1 pageFocal Press The Darkroom CookbookMatthew SimmonsPas encore d'évaluation

- Fashion Constructed Image Brief 2014Document12 pagesFashion Constructed Image Brief 2014BA (Hons) Photography, Contemporary Practice100% (1)

- TEGEAP Inside Pages PDFDocument172 pagesTEGEAP Inside Pages PDFLê KhôiPas encore d'évaluation

- Speos Brochure enDocument44 pagesSpeos Brochure enSpeos VallesPas encore d'évaluation

- Photographic FilmDocument8 pagesPhotographic FilmLemuel BacliPas encore d'évaluation

- Indirect Answers: Douglas Crimp On Louise Lawler'S Why Pictures Now, 1981Document4 pagesIndirect Answers: Douglas Crimp On Louise Lawler'S Why Pictures Now, 1981AleksandraPas encore d'évaluation

- Quentin Bajac - Age of DistractionDocument12 pagesQuentin Bajac - Age of DistractionAlexandra G AlexPas encore d'évaluation

- 2010 Fantastic ManDocument10 pages2010 Fantastic ManRenataScovinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Becker - Photography and SociologyDocument26 pagesBecker - Photography and SociologyDiego CamposPas encore d'évaluation

- Approaching Invisibility Experiencing The Photographs and Writings of Minor White Paul Sutton PDFDocument12 pagesApproaching Invisibility Experiencing The Photographs and Writings of Minor White Paul Sutton PDFferlacerdaPas encore d'évaluation

- MoMA Lange PREVIEW PDFDocument25 pagesMoMA Lange PREVIEW PDFPelayo Baquero Sánchez100% (1)

- Photography and SociologyDocument26 pagesPhotography and SociologyIntan PuspitaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes On Love and Photography. CadavaDocument32 pagesNotes On Love and Photography. CadavaJack Martínez AriasPas encore d'évaluation

- Criminalistic SDocument83 pagesCriminalistic SChe EllePas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Visual Arts Module FinalsDocument54 pagesReading Visual Arts Module FinalsMicah PioquintoPas encore d'évaluation

- VEC400/402HC high performance colour camerasDocument2 pagesVEC400/402HC high performance colour camerasAbdelhamid SammoudiPas encore d'évaluation

- Practice Test 2Document6 pagesPractice Test 2Heba ElmeniawyPas encore d'évaluation

- DSU Brand Manual WebDocument134 pagesDSU Brand Manual WebSri SukmawatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Summer 2014 Calumet Focus CatalogueDocument68 pagesSummer 2014 Calumet Focus CataloguecalumetphotographicPas encore d'évaluation

- Bosch Vdi-244v03-1Document2 pagesBosch Vdi-244v03-1Muhammad Asif RazaPas encore d'évaluation

- Filmbox User GuideDocument18 pagesFilmbox User GuideLisardo MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- (PTZ Indoor) SD22204I-GC - Datasheet - 20180129Document3 pages(PTZ Indoor) SD22204I-GC - Datasheet - 20180129Angga SenjayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual Camara SanyoDocument50 pagesManual Camara SanyoBrandin RoveloPas encore d'évaluation

- Consent Form Test Day Photo and Verification Process 0Document1 pageConsent Form Test Day Photo and Verification Process 0B WPas encore d'évaluation

- 360x180 Panorama Creation GuideDocument9 pages360x180 Panorama Creation GuideAna MPas encore d'évaluation

- Canon Eos 5000 QDDocument63 pagesCanon Eos 5000 QDMarli RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Instr Sony Ericsson c702 EngDocument86 pagesInstr Sony Ericsson c702 EngHichem CasbahPas encore d'évaluation

- Five Goals New Years PhotographyDocument14 pagesFive Goals New Years PhotographyfairyhungaryPas encore d'évaluation

- Marshall McLuhan - Myth and Mass MediaDocument11 pagesMarshall McLuhan - Myth and Mass MediaDaniel DavarPas encore d'évaluation

- Measuring Negative Focal LengthsDocument5 pagesMeasuring Negative Focal Lengthswardendavid5591Pas encore d'évaluation

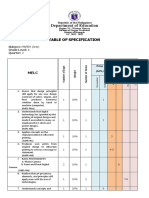

- MAPEH (Arts) Grade 6 Quarter 3 Table of SpecificationDocument2 pagesMAPEH (Arts) Grade 6 Quarter 3 Table of SpecificationVenna Grace OquindoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gullickson's Glen by Daniel SeurerDocument15 pagesGullickson's Glen by Daniel SeurerasdaccPas encore d'évaluation

- PhotoBook PDFDocument11 pagesPhotoBook PDFnicolejfortinPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes in MILDocument4 pagesNotes in MILAstrynePas encore d'évaluation

- Guidelines For of Online and Face-To-Face Activities For Foundation Day 2022 I. Traditional Poster Making Contest (Online Competition)Document15 pagesGuidelines For of Online and Face-To-Face Activities For Foundation Day 2022 I. Traditional Poster Making Contest (Online Competition)Mich ResueraPas encore d'évaluation

- Photojournalism Is The Process of Story Telling Using TheDocument50 pagesPhotojournalism Is The Process of Story Telling Using TheNaga Praveen PingaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Digital Photography Workshop Shortlisting QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesDigital Photography Workshop Shortlisting Questionnaires2sarathPas encore d'évaluation

- RoyalZProduction Music Video GuideDocument60 pagesRoyalZProduction Music Video GuideDamien GauranandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 1 Culture and ArtsDocument17 pagesUnit 1 Culture and ArtsShobana SubramanianPas encore d'évaluation