Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

City Limits Magazine, October 1994 Issue

Transféré par

City Limits (New York)Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

City Limits Magazine, October 1994 Issue

Transféré par

City Limits (New York)Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

--_ . --_----------_. _. _-- -. .

--------

-----==::. -. . _ti

-------. "

$2. 50

. . . . . _-. . . . . . . . . -

:

' , ' I

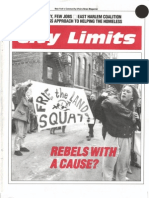

--October 1994 NewYork' s UrbanAffairs NewsMagazine

TIMES IcaUA~E TW. 9~STEP. _{I!UBLIC _!IOU"'!. RE-gRGAN~~

-WH~N ENV~R~NMENTAL MOVEMENTS COLLIDE . .....

I

. ,

- - - - - IJ IOND - G 0 0 l l 1 IUV& - .:

__ - - .. TreatI: ii .......... dl eut=8ke el tizeD s- -

. . --- . _ _ . -- . . -~ - . -. _ -. , . ' I C" -' _

-

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ~-

~-. .-. --~. . . . . . . . . _____ ----.

- - - - - - - - - - - - : : : : : : ...

" - - _ _ _ _ _

-""'. ''':100. .

-

-

.... -. .

-

- - - _-

, _

--. .

. -

-_

. . . . . . ~. -~. ----

~

-

-_

. _

-

--

-"--. _. , . ---

-

- - - ......- -

. . . : - - .

. -

--.

-.

Citv Limits

Volume XIX Number 8

City Limits is published ten times per year.

monthly except bi-monthly issues in June/

July and August/September. by the City Limits

Community Information Service. Inc . a non-

profit organization devoted to disseminating

information concerning neighborhood

revitalization.

Editor: Andrew White

Senior Editor: Jill Kirschenbaum

Associate Editor: Kim Nauer

Contributing Editors: Peter Marcuse.

James Bradley

Production: Chip Cliffe

Advertising Representative: Faith Wiggins

Office Assistant: Seymour Green

Proofreader: Sandy Socolar

Photographers: Steven Fish. Andrew

Lichtenstein. Gregory P. Mango

Sponsors

Association for Neighborhood and

Housing Development. Inc.

Pratt Institute Center for Community and

Environmental Development

Urban Homesteading Assistance Board

Board of Directors*

Eddie Bautista. New York Lawyers for the

Public Interest

Beverly Cheuvront. City Harvest

Errol Louis. Central Brooklyn Partnership

Mary Martinez. Montefiore Hospital

Rebecca Reich. Low Income Housing Fund

Andrew Reicher. UHAB

Tom Robbins. Journalist

Jay Small. ANHD

Walter Stafford. New York University

Doug Turetsky. former City Limits Editor

Pete Williams. National Urban League

Affiliations for identification only.

Subscription rates are: for individuals and

community groups. $20/0ne Year. $30/Two

Years; for businesses. foundations. banks.

government agencies and libraries. $35/0ne

Year. $50/Two Years. Low income. unemployed.

$10/0ne Year.

City Limits welcomes comments and article

contributions. Please include a stamped. self-

addressed envelope for return manuscripts.

Material in City Limits does not necessarily

reflect the opinion of the sponsoring organiza-

tions. Send correspondence to: City Limits.

40 Prince St.. New York. NY 10012. Postmaster:

Send address changes to City Limits. 40 Prince

St.. NYC 10012.

Second class postage paid

New York. NY 10001

City Limits (ISSN 0199-0330)

(212) 925-9820

FAX (212) 966-3407

Copyright 1994. All Rights Reserved. No

portion or portions of this journal may be

reprinted without the express permission of

the publishers.

City Limits is indexed in the Alternative Press

Index and the Avery Index to Architectural

Periodicals and is available on microfilm from

University Microfilms International. Ann Arbor.

MI 48106.

2/0CTOBER 1994/CITY UMITS

Giuliani's Plan

A

few hundred people congregated in a Bedford-Stuyvesant auditorium

one rainy day last month to hear Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and

Housing Commissioner Deborah Wright announce their new strategy

for turning over to the private sector hundreds of occupied, city-

owned in rem apartment buildings. The plan includes three components,

most notably the Neighborhood Entrepreneurs Program (NEP), which aims

to sell buildings to small property owners in Harlem, Central Brooklyn and

the South Bronx. The other two pieces include an improved tenant owner-

ship program and community-based nonprofit management.

The NEP program will be managed by the New York City Partnership;

potential owners will have to spend three years learning the ropes and

proving their competence before actually gaining title to the properties. They

will also be subject to the oversight of a neighborhood "task force" of business

people and community leaders. The buildings' residents are mostly low

income families who cannot afford to pay the kind of rent that would make

private ownership profitable, so the city will pair the occupied buildings

with empty ones that can be rehabilitated and rented at higher rates; the latter

will subsidize the former.

It is good news that the administration is setting out a coordinated strategy

for investing in the rehabilitation of this vital housing stock. But so far, the

plan remains vague. There are no regulations yet, no list of specific buildings

and it is not clear who the "entrepreneurs" will be. There has been talk of

forming joint ventures between large established management firms and

small, relatively inexperienced local entrepreneurs.

Also unanswered are a few fundamental questions. If in rem buildings are

sold, we will lose a critical resource for housing homeless families at a time

when the shelters are so full that hundreds of families continue to spend their

nights trying to sleep on the floors of welfare offices.

And what role will tenants have in deciding whether their building goes

into the NEP program or one of the other alternatives-that is, tenant or

nonprofit ownership? After all, they are the people with the most at stake.

Will they have a role on the neighborhood task forces that act as NEP

watchdogs? Commissioner Wright answered this question by saying "tenant

organizations" will have a role. But this is not necessarily the same as

including the tenants of the buildings themselves. This should be clarified.

In Bedford-Stuyvesant, when one tenant asked this question, Mayor

Giuliani's response sounded good. "The desire here is to work with you to

establish the very best plan for your building .... If you are the best people to

run your building, you will be it." But tenants have heard these promises

before. Let's hope this administration lives up to them.

* * *

A couple of updates:

The dream prevails: The East New York Urban Youth Corps reports that

the open air drug market highlighted in "Drugs and the Dream" (Feature, May

1993) has been shut down. Now, on Friday evenings, parents sit on the

sidewalks of Williams Avenue while their children play. The block was

closed to car traffic for much of the summer, creating a vibrant playground-

and a much happier community.

Also, a state Supreme Court judge has enjoined the city from awarding a

contract to Personal Touch, a for-profit home care service for the elded y. The

contract was supposed to replace the work of four nonprofit agencies at a

cheaper cost. But as Irwin Nesoff wrote in his Cityview column ("The

Profitization Vanguard," August/September 1994), Personal Touch didn't

have to comply with the same city operating guidelines as the nonprofit

agencies. The judge has at least tentatively agreed, saying that the contracting

process was not fair and equal, as the City Charter requires. 0

Cover design by Lynn Baldinger. Illustration by Justin Hawkins.

~

SPECIAL REPORT ON HARM REDUCTION

Quality of Mercy 18

There's a new approach to dealing with drug addicts: treat them with

respect. by Jill Kirschenbaum

The Frankfurt Resolution 20

European cities are trading in police cars for mohile medical units.

by Stephen ArrendeU

The Legalization Debate 22

Foes claim legalizing drugs will dramatically increase their use. Support-

ers say statistics show otherwise. by Stephen ArrendeU

Race, Drugs, Imprisonment 24

As the saying goes, whites do the lines, blacks and Latinos do the time.

FEATURE

Bitter Justice 14

A fractious debate over a proposed paper recycling plant in the South

Bronx threatens New York's environmental justice movement.

by James Bradky

L.A. REPORT

New Age Dawning 6

Forty poor families took ownership of their decaying apartment building

from an absentee landlord, and the city of Los Angeles kicked in the

money to do it. Sound familiar? by Lucille Renwick

PIPELINES

Spiked 10

The strange story of Farkas v. Farkas, a custody decision of critical

importance for battered women. by Kim Nauer

Restoring Trust 12

Public housing tenant associations are waking up to their potential-and

this time they have the money to make a difference. by Kate Lebow

COMMENTARY

Planwatch 26

Times Square Fleece Train by Robert Fitch

Cityview 27

Housing and Jobs Together by Nancy Biberman

Review 29

Build Them Up by Bob Blauner

12

14

18

CITY UMITSIOCfOBER 1994/3

BRIEFS

Crime Bill Woes

Little funding for youth

Now that Congress has finally

ended debate over the crime bill

and President Clinton has signed

the $30.2 billion measure into law,

it's time to take a look at some of

that "pork" Republicansopposed

with such passion.

When senators like New York's

own Alfonse O'Amato mocked

the bill's soft money, they were,

of course, talk-

ing about the

measure's

crime preven- -_

tion programs.

As it turns out,

their jeering worked. When the

eleventh-hour negotiations con-

cluded, two-thirds of the $3 bil-

lion in cuts had come from the

Shelter/Union Squabble

Labor activlets continue to

charge the citY. largest n0n-

profit shelter operator, Homes

for the HomeIeII. with union

busting and unfair treetment.

more than two .,..... after the

first complaints were aired.

In late summer, the non-

profit withdrew recognition of

the union representing em-

ployees at a Queena shelter.

Shortly after, a

union orga-

nizer filed as-

sault charges

agaln8t two

administrators

and a aec:urIty

guard at the

facility, claiming they had

beaten him.

MI haven't experienced this

kind ofviciousne. from any of

our employers. "says organizer

Ben Weinthal of DistrIct Coun-

cil 1707 of the AmerIcan fed-

eration of State, County and

Municipal Employees. DC 1707

repre.ents about 35 ca.e-

worker. and social .ervice

professionals at the Saratoga

Interfaith Family Inn in Jamaica,

the Isrgest of Homes for the

Homeless' four shelters, hous-

Ing more than 220 families.

The Saratoga workers voted

to join DC 1707 in November

1992. After two years of wran-

gling with management the

caseworkers unanimoualy

ratified a contract in late July.

Or at least they thought they

had ratified a contract.

Weinthal says the company

immediately disavowed the

contract and then pulled out a

decertification petition signed

4/0CTOBER 1994/CITY UMITS

months earlier by a number of

workers oppoeed to the union.

When Welnthal subsequently

attempted to visit shop ateward

Freddie Toomer on August 10, he

says a security guard knocked him

down. He was charged by police

with treapa88lng.

Homes for the Homeless Vice

President Aurora Zepeda says

that the nonprofit withdrew re-

cognition of the

union citing

Mbad-faith neg0-

tiations- and

calls DC 1707's

union-busting

charge.

Mabsolutely

false." She says Homes for the

Homele. has never harassed

union members and that it never

agraecl to the contract workers

ratified. Zepeda adds that it was

Welnthal who started the fight at

the Jamaica shelter by shoving

two administrators after he was

denied access to the building.

All of the organization's work-

ers are unionized, she continues,

and the National Labor Relations

Board (NLRBt has never found

the company guilty of any wrong-

doing.

In the last two years, at least

nine charges filed by the union

have been withdrawn, settled out

of court or found to be without

merit. However, the NLRB did

issue an unfair-practices com-

plaint-roughlythe equivalent of

an indlctment-egainst Homesfor

the Homeless in September 1993.

That complaint was settled out of

court after the company agreed

to stop harassing workers and

pay a suspended union member

prevention side, reducing spend-

ing on such programs to $6.9 bil-

lion over the next six years. In

contrast, law enforcement was

granted $13.5 billion and prisons

$9.8 billion.

Youth programs were hardest

hit. Funds for youth employment,

anti-gang activities, after school

programs, police partnerships

and-you guessed it-midnight

basketball were all eliminated.

Nearly $1.3 billion in funds for

eight youth programs (and one

for senior citizens) was reduced

her loat wegee, Welnthel says.

Earlier that year, the board

iHued another complaint

against Homes for the Home-

less for Illegal surveillance of

workers and failure to recog-

nize 8 union during an orgen-

izlng drive by the Commun-

Ication Workers of America at a

Bronx shelter. This too was

settled out of court according

to Ed Sabol, a CWA organizer.

~ i 8 i. the first union to

come in that ian't completely

controlled by rnanagement and

they're completely freaked

out, - says Lauria Scocozza, a

former recreation specialist and

member of the union's negoti-

ating committee. She says it's

Mcompletely untrue- that

Homes for the Homeless hadn't

accaptedthe contract. Scocozza

says she quit a week before the

vote after being told she would

have to either take a nonunion

aupervisory position-where

she could be fired atanytirne-

or be cut to part-time status.

Five of the committee's seven

original members have been

fired, laid off or forced to quit.

according to Weinthal.

DC 1707 has since filed five

new charges with the NLRB,

alleging that management's

recent activities. including

those having to do with the

contract negotiations and

Scocozza'squitting,constituted

unfair labor practices.

'"It's the moat devastating

environment you can work In.''

insists Toomer. the union rep-

resentative at Saratoga. MEver

since I've been part of the union,

I've been harasaed.lwouldhave

quit. but I don't want to betray

my coworkers."

....... "

toa single$380 million state block

grant.

So what remained? Billion

dollar grants for new courts

dedicated to drug cases and for

combating violence against

women survived. There was also

significant new support for

community education programs,

drug treatment, urban parks and

recreation, and" gang resistance"

training.

Observers point out, however,

that the law is poorly defined.

"Now there will be a long period

in which [the agencies] translate

this vague language into opera-

tions," says Lynn Curtis, presi-

dent of the Milton Eisenhower

Foundation, a fund supporting

innovative crime prevention

programs. At this point, he adds,

it's not even clear which govern-

ment agency will oversee the

prevention programs.

Ultimately, funding for all of

the crime bill programs will prob-

ably be much reduced from what

the law provides. Congress

okayed the bill on condition that

the cost of its programs be offset

by cuts in federal jobs over the

next six years. Critics think this is

unrealistic; some predict that the

law, which touts 100,000 new

"cops on the beat." will end up

funding as few as 20,000 because

of built-in budget constraints.

Prevention programs could face

worse cuts, Curtis says. "You can

be sure prevention will be getting

less."

Still, there's no denying that

there are big bucks in the offing

for savvy non profits. Staffers at

the Association of Community

Organizations for Reform Now

(ACORN), for example, are already

looking beyond prevention pro-

grams. opting instead to target

the fat $8.8 billion allocation for

beat cops. About $1.3 billion of

that is slated for community

policing.

Steuart Pittman, ACORN's

national campaign director, says

he is doing his best to convince

Justice Oepartment officials that

at least half of this money should

be set aside for community

groups. "People agree that

community policing doesn't

work without community orga-

nizing," he says. "And if you want

community organizations to

uphold their end of the deal,

you've got to give them money."

...........

Evictions Loom

Squatters occupy Lise offices

The Local Initiatives Support

Corporation (LlSC) is staring down

a group of Lower East Side squat-

ters who are demanding the with-

drawal offunding from a housing

effort that will force their eviction.

Inc., a nonprofit group formerly

headed by City Council member

Antonio Pagan. Their plan calls

for a gut rehabilitation and the

creation of 41 apartments, 12 of

them for homeless families. The

remaining apartments will be for

families with annual incomes of

less than $25,000 for a family of

four, and will be distributed by

lottery.

BRIEFS

MThis project is going to pro-

ceed," LlSC New York director

Marc Jahr told representatives

from the five squats at a meeting

i n early September. The discus-

sion was arranged after about 25

protesters occupied LlSC's Third

Avenue offices on August23, dur-

ing a visit by LlSC national direc-

tor Paul Grogan.

In June, the City Council voted

to designate the project as part of

an Urban Development Action

Area, allowing the city to sidestep

the standard land-use review

process on the grounds that the

bui ldings are "vacant" and

"blighted."

~ ..... ...., but ... ~ I I t r ...... conIinueto blossom

Jahr says he will take moral

responsibility for the evictions

Mbecause this will create low in-

come housing."

Squatters have been living in

the buildings, located on East 13th

Street between Avenues A and B,

since 1984. Between 70 and 100

people live there now. Dubbing it

Mself-help housing," they've re-

paired the roofs and brickwork,

put in new floors and installed

new wiring and plumbing.

MWe've been in open and notor-

ious possession for 10 years,"

says David Boyle, one of the orig-

i nal homesteaders at 539 East 13th

Street. "The city can't make plans

without us."

But the city is turning the

buildings over to Lower East Side

Coalition Housing Development

~ the ThIs _, In .......... '. HeI'.ICItdIeII ............... , Is t.nded

.., RoIIbIe Crosbr .... Join lJIJ. TIle prden took the place of YKMt lot

.... .... In ..-rt, to &I1IIIl from the CIIIans CommItI8e for New YOIt ~ .

The $3.9 million cost of the

project will be provided by a $2.5

million low-interest loan from the

Department of Housing Preser-

vation and Development, in

addition to federal tax credits

channeled through the New York

Equity Fund-a joint venture of

LlSC and the Enterprise Foun-

dation that has financed the

development of more than 6,000

low cost apartments since 1989.

A similar plan for the site

stalled in 1990 after LlSC with-

I;Jli.lIJ;lSli Anti-Drug Action

For anyone struggling to wage a successful war against drug

dealers encamped in their building, the Citizens Housing and

Planning Council has just published a concise and very valuable

pamphlet, How to Get Drug Enterprises Out of Housing, by

Timothy Vance. It is a step-by-step manual that anyone manag-

ing a building can use; Vance makes clear that it doesn't take

cash to get rid of dealers so much as tenacity and brains.

Copies are $4. Call CHPC at (212) 391-9031.

drew funding rather than back

evictions. Not this time. "We' re

not going to involve ourselves in

the politics of a project if the

mission is low income housing, "

Enterprise Foundation Director

Bill Frey said in late July. Squat-

ters accuse LlSC and Enterprise

of being" manipulated" by Pagan,

who described the squatters as

Mcriminalsand drug dealers" on a

recent radio talk show.

Families in the NYC Shelter System

and Where They Stay

At the September meeting,

the squatters discussed the situa-

tion with Jahr. Ml'm a Vietnam

veteran. I' ve lived in that house

long enough for my child to have

two birthdays there. What's your

position as a human being?"

squatter Butch Johnson de-

manded. Jahr was unmoved, re-

sponding that buildings available

for low income housing are scarce

and have to be allocated "on the

basis of need, not just on some-

body moving in and squatting."

He added that he was "troubled

by displacement," but the discus-

sion ended there.

:I

"i

If

'&

J

E

:::I

Z

o

IJ88 8189 8191

Source: NYC Department of Homeless Services.

8192 8193

........ ." ..... In

... bPe ." ......... ,8194:

o OIlIer

T .. F ......

3,923

o

944

312

441

5,620

"I was surprised to see him

hold the line so hard," squatter

Peter Spagnuolo said after the

meeting.

There are at least 10 other well-

established squats in the neigh-

borhood. With the number of

vacant buildings in the area

dwindling, the city is likely to go

after these as well. Local

non profits that have so far been

hesitant to back evictions may

end up changing their minds if

they want new buildings to

develop. Steven Wishnia

CITY UMITS/OcrOBER 1994/15

New Age Dawning

Following New York's lead, the city of Los Angeles helps low

income tenants become co-op owners.

T

wo years ago, the three-story

apartment building at 738 South

Union Street in Los Angeles'

Westlake section was rapidly

decaying, another victim of poor

management and neglect destined to

join the ranks of this city's dilapidated

housing.

The residents' problems were no

different than those of many tenants

living in slum dwellings throughout

L.A. They slept in cramped rooms amid

roaches and rats. They breathed the

stench of urine and feces that wafted

from vacant apartments teeming with

trash.

Community and Liberty Hill foun-

dations to hire a building manager and

to complete an architect's study to

enlarge the apartments.

In order to ensure that the project

moves smoothly to completion, local

affordable housing advocates helped the

tenants put together a board of directors

that included a number of community

representatives. Over the next two years,

the building will be converted into a

truly tenant-controlled cooperative by

phasing out most of the community

representatives and giving tenants

majority control, says Neal Richman, a

UCLA planning professor active in

housing rehabilitation projects around

the state. He joined the tenant effort in

the summer of 1993 as a consultant and

helped them organize Communi dad

Cambria. Allan Heskin, head of the

California Mutual Housing Association,

a two-year-old group that has been

involved in resident take-

By Lucille Renwick

time, but they are unified and they have

a clear sense of where they want to go,"

says Elena Popp, a Legal Aid attorney

who has helped the tenants hone their

leadership skills.

The move to buy the building, which

lies in the heart ofWestlake-one of the

most crowded neighborhoods west of

New York City-began merely as an

effort to force the landlord, Morris

Davidson, to clean it up. The once grand

91-year old structure, with 66 units in a

three-story walk-up, began to seriously

falter soon after Davidson bought it in

1991. There were broken windows,

rotted plumbing, and the place was

infested with roaches. Violations

reported by city building and safety

inspectors prompted few repairs. By

October 1992, tenants were fed up with

the ramshackle conditions. A few of

them left, and the manager filled the

empty apartments with prostitutes, drug

The 40 tenant families, most of them

working poor Latinos who speak little

English, were frustrated. But they didn't

move. Instead, they mobilized. And with

moxie, guidance from a tenants' rights

organization, public interest lawyers and

government money, they helped form a

tenant-run nonprofit organization that

bought the building.

After a long uphill battle, starting

first with a rent strike that lasted 10

months, the organization, Communidad

Cambria, finally bought the building in

late May, making it the first such pur-

chase in L.A. of a privately-owned slum

dwelling, according to Barbara Zeidman,

assistant general manager of the Los

Angeles City Housing Department.

Zeidman said city officials are keeping

close tabs on the project to determine

whether they will invest more money in

similar ventures.

overs of single-family "Somos los

homes, helped find fund-

ing and cajole the owner

into selling the building.

dealers and gang

members, Marcial

recalls. Squatters took

over other vacant units

and the building be-

came a haunt for

troublemakers.

President of the Board

"Somos los duenos! [We're the land-

lords.] Los Duenos," exclaimed a jubi-

lant Teresa Marcial after signing escrow

papers at a tenant meeting late last

spring. Marcial, a six-year resident of

the building, is president of the board of

directors of Communidad Cambria.

The tenants could not afford to con-

tribute any of their own money to buy

the building. All of the $600,000 they

needed was provided by the city's

Housing Department through federal

Community Development Block Grant

money. An additional $1.4 million was

provided in federal funds for rehabili-

tation. And $45,000 in loans and

donations came from the California

8/0CTOBER 1994/CITY UMRS

duefiosl [We're

Heskin patterned the

purchase after New York

City's 20-year-old home-

steading and Tenant

Interim Lease programs,

which help low income

tenants buy their build-

ings and take responsi-

bility for keeping them

up to code after the city

pays for rehabilitation

work. "L.A. has been

the

playing catch up to New York City in

affordable housing issues," he says.

Community development corporations

have developed several affordable hous-

ing projects, he continues. "But no one

has taken over an occupied building to

rehab it."

Astute Advocates

The experience still amazes the

tenant leaders, four single mothers who

were nervous and insecure at initial

meetings but who have grown into astute

advocates, aware of their rights and the

law.

"The tenants have been living under

really bad conditions for a very long

Several tenants

turned to the Legal Aid

Foundation of Los An-

geles, whose attorneys

encouraged them to

start a rent strike and

put their money into

an escrow account.

Their goal was to force

Davidson to make

repairs. But they didn't count on his

response: he fired the building manager

and stopped paying the bills-electric-

ity, garbage collection, a $3,000 debt for

gas-and the mortgage.

"We just had to start taking over

because there was no one to do it for us,"

says Josephina Guzman, 40, a native of

El Salvador. She and other tenants

collected money to pay utility bills and

begin a massive cleanup of the worm-

infested garbage cluttering the hallways.

With no results from the rent strike,

tenants turned to Inquilinos Unidos

(Tenants United), a 14-year-old tenants'

rights organization based in Pico-Union,

a neighboring community. Enrique

Velazquez, director of the organization,

suggested that the tenants buy the build-

ing after he saw a newspaper story about

an offer by another slumlord to sell his

dilapidated building to tenants for $1.

Those tenants declined. These tenants

didn't.

Buy the Building

"When Enrique said for us to buy the

building, we laughed," Marcial recalls.

"We didn't think it was possible to go to

that extreme." But once the tenants

agreed to make the purchase, the pro-

cess gathered speed.

Marcial, Guzman, Teresa Lopez and

Maria Contreras were chosen as tenant

leaders. By early 1993, Legal Aid attor-

neys were teaching the tenants about

their rights. That spring, tenants who

had been skeptical of buying the build-

ing started attending meetings and of-

fering solutions. By fall of 1993, after

Heskin and Richman became involved,

the tenants had won city support, formed

the cooperative and applied for loans.

The biggest hurdle was getting the land-

lord to sell to them.

Davidson had pleaded no contest to

40 counts of code violations and lost the

building to foreclosure. The new

owner-a woman living in Minneapo-

lis-soon put the building up for sale,

asking for $1.2 million. Within a week,

the price dropped to $700,000 and

finally to $600,000. By maneuvering to

give the owner the impression that

Communidad Cambria was an organi-

zation run by UCLA professors, Heskin

persuaded her to sell them the building.

"She had to believe in us. We knew she

definitely didn't believe in the tenants."

Graffiti-scarred Hallways

The purchase won't instantly solve

problems that have festered for years.

The stucco edifice is still plagued by

drug-dealing cholos, problem squatters,

graffiti-scarred hallways and unsafe

living conditions that will take time to

eliminate.

Communi dad Cambria is embarking

on a renovation project to enlarge the

tiny studio and one-bedroom apart-

ments. Over the next year, they plan to

install new kitchens, bathrooms, floor

tiles and staircases. A seven-member

board of three tenants and four commu-

nity representatives meets every Tues-

day, sets guidelines, enforces the rules

for the building and handles the

administrative work. No decision is final

until it's approved by all of the tenants,

who vote as a collective.

For Guzman this means that she and

her two children will no longer have to

walk to a hall bathroom from their

single-room apartment and will have a

real kitchen, instead of a refrigerator

propped against the wall and a hot plate

crowded with pots.

"Sometimes you live in a condition

for so long and you start to think that's

the only way you were meant to live,"

says Guzman. "But I had to believe

something better would happen because

my kids were getting too old for us to

live on top of each other like that. "

"This is more than just a building

we' re working under," says Neal

Richman. "We're in the incipience of a

resident movement." 0

Lucille Renwick is a city reporter for the

Los Angeles Times.

Advertise in

Ci ty Limits!

Call Faith Wiggins

at (917) 253-3887.

!lBankers1i:ust Company

Community Development Group

A resource for the non-profit

development community

Gary Hattem, Managing Director

Amy Brusiloff, Vice President

280 Park Avenue, 19West

New York, New York 10017

Tel: 212 .. 454 .. 3677 Fax: 212 .. 454 .. 2380

CRY UMITSIOCTOBER 1994/7

ership

You Can

Count

I

n the South Bronx, 265 units of affordable housing are financed ...

On Staten Island, housing and child care are provided at a transitional

facility for homeless families ... In Brooklyn, a young, moderate-income

couple is approved for a Neighborhood Homebuyers MortgageS

M

on their first home ...

In Harlem, the oldest minority-owned flower shop has an opportunity to do business

with CHEMICAL BANK. .. And throughout the state of New York,

small business and economic development lending generates jobs

and revenue for our neighborhoods.

This is the everyday work of Chemical Banks

Community Devdopment Group.

Our partnership with the community includes increasing

home ownership opportunities and expanding the availability

of affordable housing, providing the credit small businesses

need to grow and creating bank contracting opportunities

for minority and women-owned businesses.

In addition, we make contributions to

commUnity-based organizations which provide vital

human services, educational and cultural programs, and housing and

economic development opportunities to New York's many diverse

communities. CHEMICAL BANK - helping individuals flourish, businesses

grow and neighborhoods revitalize. For more information please contact us at:

CHEMICAL BANK, COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT GROUP, 270 Park Avenue,

44th floor, New York, NY 10017.

Ex eel more from us.

Community Development Group

c '993 Chemical Banking Corporation

8jOcrOBER 1994jCITY UMITS

Free Water

Surve

The New York. City Department of Environmental Protection

encourages all residential building owners and home owners in

New York City to take advantage of a free Water Survey Program.

You can reduce your water/sewer bill by saving water lost to

plumbing leaks.

N. no charge, we will perform a water leak survey of your home

or building and install free water-saving devices when

applicable. In less than half an hour, we will survey your

plumbing for leaks and install:

, FREE high efficiency shower heads

, FREE low-flow faucet aerators

, FREE water-saving toilet devices

Call '8005457740 today

or

(718) 937-6600

to Schedule Free Water Leak Survey only

Water Survey Teams have picture I . D . ~ and wear uniforms

Participation in this program is voluntary DE:P

New York City

Department of

Environmental Protection

IlJdolph W Giuliani. Mayor

Marilyn Geber. Commissioner

For all other water, sewer, air and noise issues call 71 8-DEP HELP

em UMITS/OcrOBER 1994/9

Spiked!

Why a crucial court case supporting the custody rights

of battered women never made the law books

F

or Jeanne Farkas, leaving her

husband and getting a restrain-

ing order against him were not

enough to stop the violence she

endured during their marriage. Howard

Farkas still had the right to visit their

son, Jonathan-and at their Long Island

meeting spots, Howard would routinely

slap and curse his estranged wife before

returning the boy to her care.

In a particularly brutal attack later

noted in State Supreme Court, Howard

pulled up in his car with Jonathan doz-

ing in the front seat. He got out and

ordered Jeanne to get her son. When she

leaned in, he slammed the car door on

her back. The impact broke the window

and nearly sent Jeanne to the hospital.

After years of what is described in

court records as a relentlessly violent

marriage and separation, Jeanne Farkas

filed for divorce and won sole custody

ofJonathan. In 1992, Judge Elliott Wilk

cited the car door incident as an egre-

gious example of the way Howard

Farkas had taken advantage of his visi-

tation rights to terrorize his wife. The

judge cut off almost all contact between

father and son, allowing only pre-

screened letters and videotapes. With

the court's permission, Jeanne and

Jonathan moved out of state so Howard

could never find them again. "To per-

mit Mr. Farkas to learn the whereabouts

[of his former wife and son] would be a

betrayal to them both," Wilk wrote.

Wilk's decision in Farkas v. Farkas

broke new ground in case law for bat-

tered women in New York by ruling that

courts must consider violence in the

marriage as a factor when deciding

custody arrangements. Unlike 38 other

states which have explicit laws requir-

ing judges to hear evidence on marital

violence in custody cases, New York' s

judiciary can-and frequently does-

ignore such history.

Routinely Ignored

Yet in a strange twist, the Farkas

decision is every bit as hard to find as

Jeanne is. It has never been published in

the law books, nor cited as precedent in

another judge' s reported decision.

Indeed, no one knows of any New York

judge who has followed Wilk's lead.

And to this day, advocates say, an on-

10jOCTOBER 1994jCITY UMITS

going pattern of violence against a

spouse can be routinely ignored by the

courts.

While Farkas v. Farkas has become

something of a cult case within New

York City's tight battered women's ad-

vocacy network-it's been talked up in

newsletters and journals, dis-

cussed at educational seminars,

taught in law clinics and, just last

May, featured in a New York City

Bar Association panel presen-

tation-the case itself was never

published in the state's official

book of case law.

The result? Oblivion, as far as

the courts are concerned. While

the case's unpublished status

poses no problems for Jeanne

Farkas (for her, the case is closed),

it does leave other battered women

without some potentially power-

ful ammunition in their courtroom

struggles to secure safe custody

Tc

..-, _.-.. __ ._-,

..

.. 0

arrangements. Any lawyer unconnected

with the informal Farkas network would

never know the case exists.

Battered women' s advocates had

hoped the Farkas decision would help

knock family law onto a new trajectory,

enabling women with extensive proof

of abuse at the hands of their husbands

to gain sole custody of their children.

Studies show that a large percentage of

men who beat their wives abuse their

children as well: according to a study by

By Kim Nauer

Yale New Haven Hospital, the number

is as high as 50 percent. Yet the New

York legislature has refused to require

judges to even consider marital vio-

lence when making custody decisions.

That's why advocates considered Wilk's

ruling important.

Eerie ftidence: ...... -4mm pictunIs of

young JonatIuIn Fartlas and his violent father

were exlllbited In ItIte court.

"This is the first case-the first

case-based in New York to say

that violence must be a factor when

considering custody decisions. It

brought New York State into the

twentieth century," says Kristian

Miccio, a clinical law professor

and director of the Family Vio-

lence Litigation Clinic at Union

University's Albany Law School.

Miccio was the founding director

of the Center for Battered Women's

Legal Services at New York City' s

Sanctuary for Families. She was

also instrumental in getting top-notch

legal help for Jeanne Farkas, and is dis-

turbed by the lack of attention the case

received in New York's mainstream legal

community.

Unpublished Decisions

Lawyers and judges regularly use

rulings in prior cases to bolster their

own arguments and conclusions. For

exactly this purpose, law libraries are

stacked with volume upon volume of

..

legal decisions stretching back over the

years.

In theory, a lawyer has the right to

use an unpublished case in his or her

court arguments. But in reality ,lawyers

can't find unpublished decisions

through any of the standard research

methods. They are not indexed or

reprinted in the New York Supplement,

a privately published record of New

York judicial decisions, nor are they

available through on-line legal research

services, such as Lexis and Westlaw.

Even if a lawyer finds such a case

through word of mouth, problems

remain: judges and their clerks can't

easily double check the accuracy of a

lawyer's citations, so they may be skep-

tical about their validity.

Now, two years later, with no measur-

able progress in the courts, advocates

are wondering why the Farkas case never

became part of the state's accepted body

of case law. "We want to hold some-

body accountable," Miccio says. "We

want to know who makes these edito-

rial decisions."

Court Reporter

Conventional wisdom in the legal

community holds that the judges them-

selves decide what is published. But at

the trial court level, such as the State

Supreme Court, that is not the case.

As it turns out, one man in Albany,

the state Court Reporter, decides the

future of New York's lower court case

law. That man is a 20-yearveteran court

staffer named Frederick Muller. By.

mandate, his office, the State Law

Reporting Bureau, must publish all

decisions from the state's two highest

courts, the Appellate Division of the

Supreme Court and the Court of

Appeals. Any remaining staff time can

be used to edit and print lower court

decisions. Muller himself determines

which cases from the trial level are

worthy of publication although, he adds,

judges do lobby the bureau and can

exercise the rarely used option of

appealing his decisions to a judicial

panel.

"I read opinions in the evenings and

on weekends. I personally read every

opinion unless I'm on vacation, which

is rare," Muller says. His goal is to find

decisions which set out and defend a

new way of thinking about existing law.

In the Farkas case, Judge Wilk

believed his decision broke new ground

on how physical and psychological

abuse should be weighed at custody

hearings, and he sent the case to Muller's

office for consideration. As he told a

meeting of the New York City Bar

Association last May, the bureau was

the first of a half-dozen publications

that, to his surprise, didn't find the

decision important. "My guess, just from

the way this case was treated, is that

there is a greater reluctance to deal with

this as seriously as other issues."

Liberal Visitation

It is an opinion echoed by many

lawyers who work in this small but

growing area of the law. Attorney Julie

Domonkos, director of Victim Services'

Westside Office Legal Project, trains

private lawyers who volunteer to rep-

resent battered women. In her experi-

ence, she says, New York courts bend

over backwards to give liberal visitation

rights to abusive husbands, despite

statistical evidence that men who beat

their wives are also likely to beat their

children. Courts are loathe to cut off, or

even severely restrict contact, she says.

Paradoxically, those very same courts

are often quick to find a mother guilty of

neglect if she fails to get her children out

of an abusive home, Domonkos adds.

Mothers can be accused by child wel-

fare officials of "failure to protect" their

children, even in cases where only the

mother is being abused. Given this

attitude, she says, it's not surprising

that fathers like Howard Farkas con-

tinue to use court-ordered visits to

intimidate and, all too often, beat the

mother. "Today, we're still dealing with

exactly the same issues as we saw in the

Farkas case," she says.

So why was Farkas spiked? Muller

says he does not remember the specifics

of his decision, but adds it's unlikely

the case received short shrift because of

the subject matter. If anything, cases

that explore emerging areas of the law

are more likely to get published, he

observes. These include domestic cases,

those related to AIDS and HIV,

homelessness and housing rights.

"In family law I probably accept a

higher percentage of cases than in any

other area," he notes. "We receive

relatively few opinions that involve

battered women's issues, and I would

say the majority of cases that we do

receive, I accept for publication."

Following his conversation with City

Limits, Muller now says he's intrigued

and would eagerly reconsider his deci-

sion on the Farkas case. He says anyone

who is interested can resubmit the case

for consideration.

Legislative Answer

Meanwhile, a legislative solution may

be at hand. For the last six years, Brook-

lynAssemblymember Helene Weinstein

has submitted legislation requiring

courts to consider a batterer's violent

history in custody decisions. The

provision, which enjoys strong support

in the Assembly, was not included in

the sweeping court reforms that passed

through the state legislature last June,

following the murder of Nicole Brown

Simpson. However, Weinstein reports

her bill may fare better this session

since the Republican leadership of the

Senate has for the first time agreed to

address the proposal.

Advocates agree that new legisla-

tion, rather than evolution of old law,

would be best for all concerned. In the

end, it is society's judgment that really

matters, Wilk observes. "[Farkas] only

becomes a serious decision if we

acknowledge that this is a serious

problem." 0

IRWIN NESOFF ASSOCIATES

management consulting for non-profits

Providing a full-range of management support services

for non-profit organizations

o Strategic and management development plans

o Board and staff development and training

o Program design and implementation

o Proposal and report writing

o Fund development plans

o Program evaluation

20 St. Johns Place

Brooklyn, New York 11217

(718) 636-6087

CITY UMITS/QCfOBER 1994/11

Restoring Trust

Tenant organizing in public housing is about to get

a desperately needed boost.

W

hen Sandy Campbell took

over as tenant association

president of Edgemere

Houses in Far Rockaway,

Queens, the New York City Housing

Authority unceremoniously presented

her with keys to her new office. Here,

she envisioned, would be her commu-

nications headquarters, the nerve center

for a new tenant campaign to improve

maintenance and safety at this ragged

1,400-unit complex.

But when she opened the office door

last spring, she found nothing. Not even

a phone. Just four peeling walls, a floor

and "lots of waterbugs." As she later

found out, she was lucky to get that

much. Public housing tenant leaders

have traditionally received little in the

way of financial or organizational sup-

port from the government.

decide. They can also apply for addi-

tional grants under HUD's year-old

Tenant Opportunity Program. The

housing authority will receive $10 per

unit for related costs, such as election

supervisors and third party mediators.

"This amounts to some substantial

money," says Rowland Laedlein, direc-

tor of community affairs for the New

York City Housing Authority (NYCHA).

"It's certainly more than [tenants] have

traditionally been used to having."

Company Unionism

Change can't come fast enough for

many tenant activists in New York City's

vast public housing system. Consider-

ing the sheer number of people who live

there-more than 600,000 residents

reside in NYCHA's 330 developments-

By Kate Lebow

Officials will only negotiate with tenant

associations whose bylaws they

approve, and they retain the right to

intervene in tenant association elections,

even to overturn the elected board in

certain circumstances.

"[NYCHA] claims they want this to

be a democratic process," says Janet

Cole, president of the tenant associa-

tion at Queensbridge Houses in Long

Island City. "But this is the housing

authority's process."

Witness Sandy Campbell's problems

at Edgemere.

Like other public housing tenants,

Edgemere's residents have a host of

legitimate complaints. They can point

to holes in their ceilings, mice in the

hallways and appliances that go hay-

wire. The grounds have been ill-kept

and all of the buildings

lack basic protections like

intercoms and entry

locks. Believing that the

previous president had

done little to improve the

situation, Campbell says

she and a slate of five

others, all trained by the

Association of Commu-

nity Organizations for

Reform Now (ACORN),

ran for office last Febru-

ary in the hopes of mak-

ing some real changes.

The flyers and out-

~ reach they did for the elec-

(/)

~ tion worked, Campbell

'"' says. Her slate won and

g dozens of tenants began

New regulations from

the federal Department of

Housing and Urban

Development (RUD) are

expected to change that.

The rules, which took

effect in late September,

give public housing

tenants unprecedented

authority in the operation

of their own associations.

Pending expected Con-

gressional approval of

$35 million in new fund-

ing, tenant groups will

also have the money to

operate their offices and

pay for services they feel

will do the most good in

their community.

It's revolutionary, says

Maxine Green, chair of the

National Tenants Or-

'INs "ofIIce" In tile blllllllllt of ~ ....... was tile IIIOIt IIIPIIOft teunt ........

SIadJ c..npbeI CGIIId expect "-tile IIauIInc ~ -.

showing up for meetings.

The officers quickly had

a list of grievances to deal

with. But when they went

ganization and a chief architect of the

rules. For the first time, she says, "our

social and economic development pro-

grams will be operated and controlled

by tenant councils."

Each tenant association will receive

$15 per unit in their complex-a huge

increase over the 40 cents per unit they

now receive. An association represent-

ing 1,500 apartments will now have

more than $22,000 a year to spend on

training leaders, paying office staff,

hiring security or whatever else they

12/0CTOBER 1994/CITY UMITS

observers say the tenant movement has

never lived up to its potential.

A big reason has been the housing

authority'S grouchy response to aggres-

sive community action, tenants charge.

Activists complain that NYCHA's much

touted tenant participation program is

nothing more than "company union-

ism." They say that NYCHA, which

requires associations to submit their

bylaws, budgets and grant applications

for approval, uses its oversight to

undermine independent organizing.

to work, soliciting the building man-

ager with requests for improvements,

all they got was hostility. Despite a

protest sit-in at the district manager's

office and complaints to the highest

levels of NYCHA, the manager refused

to work with the new leaders, Campbell

says.

When basic improvements are not

done, tenants have little reason to believe

in their leadership, Campbell adds.

"We're here, but NYCHA doesn't allow

us to do anything. Now we've got

residents who are disenchanted, who

are screaming at us. They're saying, 'We

don't need a tenant association. It's not

doing anything. '"

Share of Trouble

Campbell is convinced NYCHA does

not want to work with outspoken

organizations. "They want you to be a

bridge club," she says.

ACORN-trained activists have had

their share of trouble with the housing

authority. Residents of Hammel

Houses, also in the Rockaways, say that

a NYCHA district official told them they

could not hold an ACORN meeting in

Hammel ' s community center. The

residents were organizing to challenge

the incumbent Hammel president-who

also happened to be secretary, treasurer,

paid head of the tenant patrol and chair

of the advisory committee for the

development's community center.

Laedlein explains that any organiza-

tion other than the elected tenant asso-

ciation would have to apply specially

for use of public areas. "If an outside

organization wanted to come in ... and

meet residents in opposition to an asso-

ciation, we might not allow that."

Meanwhile, Hammel residents com-

plain that every time they tried to get

information about the current associa-

tion' s bylaws, registration procedures,

or membership from NYCHA, commu-

nity affairs officers directed them to

deal with the president-despite the

fact that she refused to cooperate.

Finally, the night before nominations

were due for a new tenant board, ACORN

member Maxine Davis and her col-

leagues acquired a copy of the bylaws.

She and three other ACORN members

are now running for office unopposed;

the incumbent president has decided

not to run. Elections were to have been

held on August 18, but NYCHA post-

poned them until authority officials

could secure a copy of the registered

voter list, something Davis had been

seeking for months. "People become

disheartened," she says. "You stick your

neck out and you wonder what for."

Power of Stasis

ACORN is not the only outside orga-

nization that has criticized the way

NYCHA handles tenant activists.

Michael Goldblum, a volunteer fellow

of the Municipal Arts Society-a pro-

fessional organization composed

primarily of architects, preservationists

and urban planners-describes how a

group of teenagers he works with in

Claremont Village in the Bronx came up

with the idea of cleaning up the play-

ground in front of their building.

"The manager said, 'One drop of paint

and I give you all $100 fines, '" Goldblum

reports. "Especially at the local mana-

gerial level, NYCHA people can be

cautious and difficult. Any attempt to

make changes usually boils down to

efforts of the do-gooders versus the

powers of stasis. "

NYCHA's attitude toward outside

organizations is important because many

activists have found that, despite

NYCHA's policy of recognizing only

one legitimate tenant body, it is often

more effective to work outside the formal

tenant association structure. Goldblum

helped an informal committee of tenants

in Claremont Village secure $70,000

from NYCHA to redesign and rebuild

the grounds of Morris Houses. And hun-

dreds of public housing residents have

organized with church groups like

Brooklyn Ecumenical Cooperatives and

South Bronx Churches' Tenant Union

for Public HOllsing to demand repairs

and improved security.

Winners and Losers

NYCHA's Laedlein insists his office

would never use its power to weaken or

dismantle legitimate tenant leadership.

"They can agree with us or disagree

with us," he says. "Our position is that

it shouldn't make any difference to us as

a department who wins and who loses."

Still, he concedes, the perception is

understandable. His office is just now

completing a two-year survey that

. reveals a tenant council system in dis-

repair. Many associations are only

sporadically active. Others haven't been

following the rules. Most haven't had

elections in the last three years and in a

few cases, more than a dozen years had

gone by. "Very, very few-probably only

a handful-were within the terms of

their bylaws, " he says.

Today NYCHA is trying to clean up

after a decade of neglect. As a result, the

last year and a half has been marked by

disputes with some tenant leaders who

had come to believe that their proce-

dures were legitimate. "Many have re-

solved the issues," Laedlein concludes.

"For the few that did not, we have

[gathered] the residents and re-held

elections. "

But some association presidents feel

NYCHA is going overboard. Janet Cole

of Queens bridge Houses is one of several

leaders who have been given NYCHA's

ultimatum. Officials told Cole they

would hold new elections unless the

tenant association changed a bylaw

reqUlrmg residents to attend nine

meetings before being eligible to run for

office.

Laedlein charges that the rule is un-

democratic and that Cole opposes

broader tenant involvement. But Cole

feels her nine-meeting rule is reason-

able and could be defended in court.

Cole was one of a group of tenants who

successfully challenged NYCHA in

court over interference in elections in

1992-and she says she will do it again.

Cole' s attorney, Judith Goldiner of

the Legal Aid Society, says the housing

authority has a real problem yielding

control. "My view is that NYCHA would

like to control the associations as closely

as possible. And if people get elected

who they can't control, they want to get

rid of them."

Detailed Regulations

Presumably, BUD's new regulations

will end the disputes over bylaws and

election procedures. The rules are very

detailed and provide a way for associa-

tions to appeal grievances to BUD. If

NYCHA follows the guidelines, tenants

will no longer be able to argue that the

agency is making up its own rules.

There is no getting around the fact

that HUD's new regulations will require

large doses of cooperation between

tenants and the authority. Over the next

year, NYCHA and tenants will have to

hammer out dozens of new procedures

together. And this begs a question: will

a plan that depends so heavily on coop-

erative planning be successful in New

York City?

For his part, NYCHA's Laedlein

promises that resident groups will

control the new budget process. "We'll

have to develop some general guide-

lines, but I think the intent is for us to

accept any reasonable recommendations

for how the associations want to spend

their money."

As for Sandy Campbell, she says she'll

stick with her strategy of screaming and

yelling. In early September, NYCHA

called to tell her that Edgemere's prob-

lematic building manager had been

transferred. Days after the new manager

took over, staff began attending to the

many festering maintenance problems.

Workers have even begun installing new

intercom security systems, Campbell

says. "It was shocking, " she says glee-

fully. "They told me: ' Well, Ms.

Campbell, you really put the Rockaways

on the map.'" 0

Kate Lebow is a Brooklyn-based

freelance writer.

CITY UMITS/OCTOBER 1994/13

shouting match spilled out onto the streets of

Mott Haven a few weeks ago. It didn't have

anything to do with love, or much to do with

traditional Bronx politics. It was a fight about

the future of the neighborhood, environmen-

talism, jobs, and who should decide how empty land

is put to use.

The odd thing is that the participants were leaders of well-

respected South Bronx community groups-and they were at

each other's throats, just a

punch or two away from a

full-fledged brawl.

battered ecology. Sustainability is their mantra, a vision of

clean methods of production for all sorts of products, conver-

sion of the waste stream into a raw resource for manufactur-

ers, improved means of transportation, new development

carefully planned to minimize pollution. The paper com-

pany project appeared to be a perfect symbol of this kind of

future. Even Vice President Al Gore has given his blessing to

the plan.

Over the past few years, several efforts had been under-

taken to bring such an op-

In one corner was the

Banana Kelly Community

Improvement Association,

a multimillion-dollar non-

profit that manages and

develops affordable hous-

ing. (Its name comes from

the banana-shaped curve of

Kelly Street, where the

group was born 17 years

ago.) In the other, the much

younger South Bronx Clean

Air Coalition, a scrappy

alliance of neighborhood

activists who originally

joined forces in an attempt

ustice

eration to the South Bronx.

One involved a Florida-

based company called Pon-

derosa Fibres, which until

recently sought to build a

newsprint de-inking mill in

the Harlem River Yard. At

the same time, Banana

Kelly and the Natural Re-

sources Defense Council

(NRDC), one of the

country's most prominent

environmental organiza-

tions, pursued similar

BY JAM E S

to shut down a medical waste incinerator in

Mott Haven in 1991.

BRADLEY

plans of their own. In Feb-

ruary, 1993, NRDC even

paid for several borough

and city officials, along

with Yolanda Rivera of Banana Kelly and

Banana Kelly wants to build a paper recy-

cling plant in Mott Haven and is lining up

developers and financial backers for the project.

The Clean Air Coalition disagrees with the

proposed site for the plant-the abandoned

Harlem River rail yard-and wants more

details; its members say their demands for

wider community discussions and public

participation have been ignored. So when the

state Urban Development Corporation, one of

the project's sponsors, scheduled a one-hour

.A 50utll Bro ...

Nina Laboy of the South Bronx Clean Air

Coalition, to travel to Sweden and meet

with officials from MoDo, a paper recycling

firm.

paper mill plan

So when Ponderosa dropped its plan

last April, Banana Kelly stepped in and on

May 6th the new deal was announced.

According to the preliminary plans, which

still must undergo a number of approval

and permitting procedures, the $200 mil-

lion plant will be owned by Banana Kelly,

splinters tlte

enllironmental

mo"emen'

public hearing in the mitldle of a work day last month-and

didn't tell anyone in the neighborhood except Banana Kelly

and the community board-serious trouble was just around

the bend.

ew people associated with the Mott Haven plan

I!Ul!I!IIIIII'If-U'U anything about this project to turn sour. Press

,age has been glowing; environmentalists around the

" ~ t l ' ' ' are already citing Banana Kelly's proposed "Bronx

Community Paper Company" as a model scheme,. the long-

awaited nexus of progressive neighborhood revitalization

and the cutting edge of environmentalism. Urban planners

have spent years searching for new ways to promote eco-

nomic growth and jobs without further damaging the city's

14/0CTOBER 1994/CITY UMITS

S.D. Warren, a Boston-based subsidiary of

Scott Paper Company, and MoDo. It will be a state-of-the-art

de-inking facility designed to turn discarded office paper into

high-grade pulp for use by a paper mill in Maine.

The project's promoters also promised 275 new full-time

jobs for local residents, as well as a day care center and quality

job training services. The South Bronx would gain a major

new business; its residents, new employment opportunities.

And NRDC could guarantee an ecologically-sound industrial

facility that would produce no affronts to the air, land or

water. Supporters thought the community-based credibility

of the project would be further boosted by the fact that NRDC

had in its employ Vernice Miller, a longtime Harlem environ-

mental leader and executive director of West Harlem Envi-

ronmental Action (WHE ACT). Miller has been widely recog-

nized as a pioneer in the field of environmental justice,

organizing against the siting of polluting industries in com-

munities of color.

Why, then, a few months after the proposal's unveiling,

has the air in Mott Haven become so toxic with vitriol and

rhetoric that environmental activists all over the city are

choking on it?

NRDC and Banana Kelly's repeated claims

community support, the paper recycling

a long way from winning the unqualified backing

Bronx residents. Indeed, a number of local people

these organizations with having arrogantly presumed

that neighborhood residents would support the plan simply

because a local nonprofit was involved.

"They're coming in saying, 'Take my word for it. It's a good

[project],'" says Carlos Padilla, a member of the South Bronx

Clean Air Coalition. "It might very well be. But we just want

certainly emerged from the grassroots of Kelly Street, that

was many years ago. Like many activist organizations of the

1970s that have grown into technically proficient housing

and service providers, Banana Kelly has its critics. "Banana

Kelly has a reputation in the community as an agency. That's

what they are. They're not a movement," protests Vicente

"Panama" Alba of the National Congress for Puerto Rican

Rights.

And the "extremists" Hershkowitz condemns include a

number of people with a solid reputation for demanding-

and getting-real grassroots participation in community plan-

ning. The successes of Nos Quedamos are well known. And

it was the South Bronx Clean Air Coalition that dogged

officials and journalists for years, directing them to stay on

the tail of Remtech, the private company that built Bronx

Lebanon Hospital's notorious medical waste incinerator.

Ultimately, these activists helped uncover the inept financial

planning of that project, leading to its untimely bankruptcy

and a congressional investigation.

Now, the same organizations have focused their

Sout h

Clean

the facts. They said they

had no need to answer

them, that they know it's

safe and that should be

sufficient." Several mem-

bers of the Clean Air Coa-

lition say they are await-

ing proof of the plant's

environmental sound-

ness, and that they are

unwilling to take the de-

velopers' word-no mat-

ter whose it is-that all

'A suit ' hem

Coalition

NOR'l'llBRONx

CLZAN AIR

Ri IS g tiled as a chaJ/

ad' Ver Yard Ventures plan which. enge the approval ofalla"'e

lS8Sterous e1fect on the econom a

CCO

d

rdlng to plaintiffs wil1 ha In

Y an erJvironm ' ve

COALITION,

eln PlU!ss_

rUHiHONI'l'v

WILL SI enl of Ihe Bronx.

WILL GNIFrCANlLY INCREASE

ON 'l'/IE HOvE:

is well.

"This project is be-

ing rammed down our

throats," agrees Yolan-

da Garcia, leader of

REDUCE NEW JOBS FROM 23 TRAFFIC ON AREA ROAD

APPROX1MATEL Y 800 S

"Stnce freight llIil .

SOO! as trudcs engines 8CIlcrale about 0

lJU&sj IR Ptoponion 10 .he l<>adslb ne"cnlb as mUCh eliesel

D8 OIl' on a valuable op cany. Ihc oily is

;:",,,,,",,on. and ,'.... air IlOrtlWly 10 n:du", lruclc

polJUtion .t generates,"

KloaoflhcSierra ClUb.

Nos Quedamos (We ""'1'1

Stay),agroupofSouth

Bronx residents who ").,

Greenpeac;e

turned the traditional

city planning process While IIouw. ""'Qed

"w.,. !he.....

on its head last year reeyel ... Jobs v c.

by demanding-and

winning-the right v .... bIe -roe =',l.nI.

J ..... Ada"'.. 4"

to redesign a city H H., raJ

arlem River Yard Ventures H ,U R_ius DeI_ Councit West q

blueprint for their State offie aJ . . ar,em En

neigh b or ho 0 d, I s SlII1IlarlYdefeoddleirdeeisioo to award 99vlronmental Action t:

Melrose Commons. a -Year lease bed;:

as 00 a short-teno study not a

Down at West 20th Street in Manhattan, Allen . :l

Hershkowitz, a senior scientist with NRDC, dismisses the attention on the Harlem River

critics. He says they represent a disgruntled minority and Yard, a wide swath of land at the southern tip of the Bronx. !

should not be taken too seriously. "Grassroots organizations In 1989, the state awarded a 99-year lease to Harlem River

that have been fighting to take over their community have Yard Ventures, a group of politically-connected developers

finally gotten the opportunity to control $200 million of (See City Limits, "Stopping Freight Dead in its Tracks,"

investments," Hershkowitz explains. "But the whole opera- January 1994). The developers plan to build an industrial

tion is being fought by a small group of extremists." park on the site, despite the $175 million the state and city

..

But who, exactly, defines grassroots? While Banana Kelly have spent to build a link to the yard so that it can become the ;::l

CITY UMITS/OCTOBER 1994/18

centerpiece of a revitalized, modern freight rail system.

Environmentalists have long argued that New York lacks

adequate freight rail facilities, contributing to a tremendous

increase in truck traffic and air pollution.

What's more, critics say, the Harlem River Yard develop-

ment deal was shrouded in secrecy, with no community

involvement beyond a few discussions with political leaders.

Unfortunately for Banana Kelly and NRDC, the proposed

paper plant is part of the Harlem River Yard industrial park

development-along with a waste transfer station and a

scaled-down version of the freight rail facility. On August 17,

the Clean Air Coalition and several other groups, along with

67 individuals, filed a lawsuit against the State of New York,

challenging the legality of its lease with Harlem River Yard

Ventures. "We happen to be caught in the middle ofit, " says

Vernice Miller ofWHE ACT and NRDC.

ina Laboy of the South Bronx Clean Air Coalition

that the site of the paper plant is not the group's

"When you have a de-inking facility that will

sulfur emissions, next to a power plant, next to a

station, [there is] the communal effect of all

those facilities," she says. "There needs to be public input."

According to Hershkowitz, community concerns are un-

founded. He says the facility will be the cleanest, most

efficient, most advanced de-inking plant in the world. The

mill will take in 600 tons of office paper a day, turn it into 470

project. "From the moment it was conceived we used a very

extensive process to make sure that the community was in

favor of[the de-inking mill] and that they knew what we were

doing," she says. Rivera cites two organizations she has

worked closely with on the project: ACT Mott Haven, the

local chapter of Agenda for Children Tomorrow, an organiza-

tion that seeks to improve coordination of services for youth;

and the South Bronx Community Collaborative, a Hunts

Point group that organizes meetings bringing together local

nonprofit social service providers.

Confirming these accounts proves difficult, however. John

Sanchez, cochair of ACT Mott Haven, says the group will not

endorse the Banana Kelly plan until final environmental

impact reports are proffered. Moreover, he says ACT has

never considered the question of rail freight in the Harlem

River Yard. "Banana Kelly, which has participated in our

group, came up with one idea, and that's what we con-

sidered," he says. "Tomorrow, if someone comes up with

another idea, we would probably want to consider that [too]."

As for the South Bronx Community Collaborative, Hunts

Point nonprofit leaders say it is essentially a creature of

Banana Kelly itself, designed to coordinate an application for

social service funding from the state. Yolanda Rivera serves

as its chair.

And contrary to Hershkowitz's assertions, Community

Board 1 and other elected officials have not endorsed the

paper plant. Robert Crespo, CB l's district manager, admits to

knowing little about it. "We have met very briefly with

Banana Kelly, just to hear the concept," he says. "We have not

tons of pulp and transport it to Maine by rail.

The pulping process will use water, not chlo-

rine, says Hershkowitz. The plant's source of

power will be a natural gas fired steam boiler,

which will emit less than 25 tons of nitrogen

oxides per year, within the limit mandated by

the state.

me Harlem

done any research, we have not taken any

action concerning this particular project." A

spokesperson for Fernando Ferrer says the

borough president is reserving judgment on

the plan until backers present an environ-

mental impact statement. Bronx State Sena-

tor Joseph Galiber, whose district borders

the area, has been publicly critical of both

the Harlem River Yard deal and NRDC's

advocacy of the de-inking mill, which he

believes is bad for the area. State Senator

Pedro Espada offers tentative support for the

project, adding that he is awaiting an envi-

ronmental analysis.

.iverYarel

delle'opmeat

But the mill will also produce consider-