Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Crim Pro Two OUTLINE

Transféré par

annamelicharDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Crim Pro Two OUTLINE

Transféré par

annamelicharDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

PREAMBLE.

WHY CRIMINALIZE?

Retribution (retaliation, revenge, eye for an eye, deontology): Immoral behavior creates imbalance that is corrected by punishment. Deterrence (utilitarian): Individual punishment serves as example for others, society knows what behavior is impermissible, instills fear to convince others not to break law. Rehabilitation (utilitarian): Change individual behavior to conform to law. Incapacitation (utilitarian): Incarceration/execution prevents individual from breaking the law.

I.

A.

CHARGING DECISIONS: Judiciary defers to executive in prosecutorial discretion, EXCEPT in

cases of selective or vindictive prosecution (extremely difficult to prove). Prosecutorial Discretion [8A1, 2]: Power to determine who to indict/charge and who NOT to indict/charge; P may determine which crimes (and Ds) are enforced and which are NOT enforced. 1. Inmates of Attica Correctional Facility v. Rockefeller (1973): Judiciary does NOT have authority to compel a prosecution, either federal or state. 2. Brogan v. United States (1998): Court will not interfere even if only .017% are prosecuted; P may charge low level crime as gateway to obtain evidence of serious crime (e.g., Al Capone tax evasion). 3. Policy Considerations a. Separation of Powers: P = agent of executive; Don't blur the line between rulemaking and rule enforcement. b. Federalism: States have sovereign power to make and enforce own laws. c. Practicality: Judiciary not equipped to supervise Ps, Court has no framework to determine whether P abused discretion, P's work product and grand jury process are secret, Protect Ds? (i.e. appointed judges would be super-Ps with no accountability), Mandamus not appropriate to force prosecution, P is politically accountable. d. Counter-arguments: Judiciary employs arbitrary/capricious oversight framework elsewhere (so not impossible), Standing makes challenging P difficult, Equal Protection should warrant consistent application of laws, P should not be able to single-handedly override Legislature, P should charge crimes and let Jury decide. e. Systemic Safeguards: Judiciary oversees some P negotiations, Some JDs elect Ps, ABA and other professional standards (e.g., conflicts of interest), Civil causes of action available. f. Factors P Considers in Charging Decisions: Likelihood of conviction, Strength of evidence, Deterrence, Resource allocation, Pressure from victims, Rehabilitation, Public scrutiny (especially in high profile cases), Strategy. Constitutional Limits on Prosecutorial Discretion [8A2] 1. Selective Prosecution: Equal Protection per 14th A. + Due Process of 5th A. a. D must show discriminatory INTENT + EFFECT. b. Wayte v. United States (1985) [draft protestor]: P's decision to charge may NOT 1

B.

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

2.

3. C.

be based on an unjustifiable standard such as race, religion, or other arbitrary classification. i. Intent: not shown because P's criteria were publicity-neutral. ii. Effect: not shown because Gov'ts beg policy meant similarly situated Ds, both politically outspoken and not, treated similarly. c. United States v. Armstrong (1996): To prove race-based prosecution, D must show: similarly situated individuals of a different race were NOT prosecuted. i. Very difficult standard to meet. ii. To obtain Discovery: D must produce some E that similarly situated Ds of other races could've been prosecuted, but weren't. d. D must overcome presumption that P did not selectively prosecute. Vindictive Prosecution: Due Process of 5th A. a. Wayte: P's decision to charge may NOT be based upon the exercise of protected statutory and constitutional rights. b. Presumption of Vindictiveness: In certain circumstances, though limited. i. Blackledge v. Perry (1974): P sought greater charges after D appealed conviction; Court held a reasonable likelihood of VP even though D had no direct E. ii. Presumption necessary because fear of retaliation could impermissibly deter a D from exercising statutory/constitutional rights. iii. NO VP if Gov't shows it was impossible to charge more serious crime at the outset (e.g., victim dies after first trial). iv. United States v. Goodwin (1982): NO VP when D exercises right to jury trial (Court suggested VP inapplicable to exercises of all pretrial rights). Remedy: UNCLEAR if dismissal of indictment or some other sanction (Armstrong).

Screening Charging Decisions [8B]: Extreme deference to P in GJ/PH process means only real challenge to indictment is factual/legal challenge (NOT procedural). 1. General Process: Must have Probable Cause! a. Information: Informal statement by P, only if D waives right to indictment or preliminary hearing. b. Indictment by GJ i. Ex parte: P and GJ only (no judge, no D, no D attorney), non-adversarial. ii. Secret: Fed. R. Crim. Pro. 6 requires all sworn to secrecy except Ws. iii. D may waive GJ, burden for P gives incentive to bargain out of it. iv. Result: GJ almost always issues indictment (99%). 2. The Grand Jury: 5th A. right to GJ only if federal felony (NOT incorporated to states). a. Costello v. United States (1956): OK that Indictment based on only hearsay E. b. United States v. Williams (1992): P NOT required to present exculpatory E to GJ. c. Policy: Time constraints, Independence of GJ = SoP issue (i.e. removed from adversarial system), Court not equipped to review GJ (inefficient, ineffective). 3. Preliminary Hearings: Before a judge. a. Public + Adversarial: P presents E to judge (D sees P's E, but has no production burden). b. Result: 3-8% cases dismissed after PH. 2

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

4.

Protections at GJ Stage: 5th A. self-incrimination DOES attach, but no right to present a defense. a. Ds guilt/innocence NOT established after indictment (only P/C). b. BUT, Ds reputation, time, emotion, money, etc. at stake. c. Cost-benefit: D's rights do NOT outweigh concerns in Costello.

D.

Joinder and Severance [8C]: Improper Joinder? 1) Properly joined under Rule 8? AND 2) Prejudice under Rule 14? REMEDY = Severance. 1. Rule 8. Joinder of Offenses and of Defendants (in same indictment) (a) Joinder of Offenses if: (1) Same or similar character, OR (2) Same transaction or are parts of the same plan. (b) Joinder of Ds if: (1) Same act or transaction, OR (2) Same series of acts/transactions constituting an offense. 2. Rule 14. Relief from Prejudicial Joinder (of trial for Ds or offenses) a. Severance required when joinder is Prejudicial. b. Zafiro v. United States (1993): Prejudice = Did joinder make it more likely that a right was infringed, jury confused, etc.? 3. Two-Part Inquiry for Improper Joinder a. Properly joined under Rule 8? b. Prejudice under Rule 14? 4. United States v. Velasquez (1985): Improper Joinder because one D not involved in one crime charged (heroin), Prejudice since other Ds charged with serious crimes. 5. Policy a. Joinder Favorable to P: Try series of bad crimes/Ds together, Efficient (e.g., one pretrial hearing, Ws, jury selection, trial prep, etc.), Evidence rules. b. Joinder Harmful to D: Guilt by association, Jury blurs crimes, Erodes presumption of innocence.

II.

A.

PRE-TRIAL RIGHTS

Bail and Detention [9A]: Grant Bail OR Excessive Bail? 1) Likelihood D will appear at trial, AND 2) Danger D poses to safety of any other person and the community. 1. 8th Amendment: Forbids excessive bail. a. Government does NOT need to offer every D bail (Salerno). b. BUT, bail offered must NOT be excessive. 2. Federal Bail Reform Act of 1984: Pretrial detention OK if at hearing judge determines that no condition or combination of conditions will reasonably assure the appearance of the person as required and the safety of any other person and the community. a. Constitutional. b. OK per Procedural DP: Hearing, counsel, C&C E. c. OK per Substantive DP: Regulatory, NOT punitive. d. Examples of Regulatory Detention: Japanese internment (Korematsu), Enemy 3

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

3.

4.

combatants (Boumedienne), Mentally ill and dangerous (Addington), Sex offender civil custody, Quarantine communicable diseases, Immigration. Defining Excessive a. Stack v. Boyle (1951): Only reason for bail is to assure D will appear for trial. b. United States v. Salerno (1987) [post-Bail Reform Act]: Gov't can deny bail and detain where D poses a danger to society with Clear and Convincing E. Bail Alternatives: Pretrial detention, D out on reconnaissance, Conditional release, Surety bond, Electronic monitoring (expensive, not always appropriate), Police monitoring (even more expensive).

B.

The Right to a Speedy Trial [9B]: 6th A. Right attaches after formal charge; If arrested but before charge: DP violation; State claim: 6th A. violation, use Barker balancing test; Federal claim: Speedy Trial Right Act violation; Remedy = dismissal with prejudice. 1. 6th Amendment: In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall have the right to a speedy and public trial. INCORPRATED to states. 2. Speedy Trial Right Act of 1964 a. Once D is charged, trial must occur within 70 days. b. BUT 70 day clock can be tolled if delay in accordance with the ends of justice. 3. SoLs: Some crimes dont have them, but most do; Federal SoL is usually 5 years. 4. Policy a. Pro-D: Delay impairs Ds ability to present defense (memory fades, E lost, Ws difficult to locate, etc.), Minimize anxiety associated with criminal prosecution, Minimize unnecessary and oppressive incarceration. b. Pro-Society: If out on bail, frustrates incapacitation; Gov't also suffers lost E, etc. AND bears burden of proof. 5. Barker v. Wingo (1972): Gov't waited 4 years to prosecute D after convicting co-D. b. Balancing TEST: i. Length of Delay: Longer = Violation more likely. ii. Reason for Delay: Better = Toleration more likely (Out of Gov'ts control? Pre-scheduled? Related to the case? Requested by D?; Bad Faith = Presumption of prejudice.) iii. Ds Assertion of Right to Speedy Trial: NOT use it or lose it, BUT very important since delay could benefit D; Assertion = Rebuttable Presumption in favor of D; BUT if D unaware of indictment, less likely to hold against D (Doggett v. United States [1992]). iv. Prejudice to D: Look to Pro-D Policy, above; No need to prove specific prejudice, delay presumptively compromises the reliability of the trial. 6. United States v. Lovasco (1977): No DP Violation. a. TEST: Was delay oppressive? D must show Gov'ts reason(s) for delay were illegitimate, Court hesitant to interfere in P's investigatory process. b. D must prove Gov't misconduct to win on DP (pre-charge) claim. 7. Remedy: Dismissal of charges with prejudice.

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

III.

A.

GUILTY PLEAS AS A SUBSTITUTE FOR TRIALS

Pleas [10A]: Must be Voluntary, Knowing and Intelligent to satisfy DP; D must be Mentally Competent; D must have Effective Counsel; REMEDY: Usually vacate plea, remand. 1. Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 11. Pleas a. Guilty, b. Nolo Contendere (no contest), or c. Conditional: D reserves right to appeal certain issue(s). 2. Voluntary, Knowing and Intelligent a. United States v. Broce (1989): Does the plea represent a voluntary and intelligent choice among the alternative courses of action open to D? (Brady) i. NOT whether guilty plea would have been entered but for Ds desire to avoid the death penalty. ii. NO DP violation: D not required to admit guilt to plead guilty. b. Voluntariness: Was D coerced? i. If coerced or induced by improper threats, misrepresentation or bribes = involuntary (Brady). ii. Brady v. United States (1970): D pled to avoid death penalty (later deemed unconstitutional for his offense). Voluntary since no E that D was so gripped by fear that couldnt rationally weigh options. iii. Requiring waiver of constitutional privilege does not make it involuntary. iv. Fed. R. Crim. Pro. 11: D must enter plea in open court (harmless error). c. Knowledge: Did D understand waiver of rights/assumption of guilt? i. D must be aware of direct consequences and commitments. ii. D must be aware of maximum possible sentence. iii. Some courts require D to be aware of potential civil consequences or revocation of conditional release (immigration: IAC if counsel fails to inform D of immigration consequences of accepting plea). iv. D must be aware of nature of rights being waived: 5th A. selfincrimination, 6th A. right to jury trial, 6th A. confrontation. v. Rule 11: D must understand consequences of plea, constitutional rights waived, nature of charges (mandatory minimum sentences, maximum penalty for offense, special parole provisions), statements may be used later for perjury prosecution. d. Intelligence: Did D understand consequences of guilty plea? i. Must show D was informed of nature of charges: Critical elements of offense(s) and available defenses. 3. Mentally Competent: To plead guilty or to waive counsel in order to plead guilty. 4. Factual Basis for Plea a. NOT required by constitution, but many statutes and rules require judge to determine factual basis exists before accepting plea. b. North Carolina v. Alford (1970): Judge may accept guilty plea from D who maintains innocence, so long as record contains strong E of actual guilt. c. Rule 11(b)(3): Court must determine factual basis for guilty pleas (NOT for nolo contendere pleas). 5

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

5.

6.

Effective Assistance of Counsel [10A2]: 6th A. right attaches in PB (critical stage). a. IAC: Court will vacate if D proves 1) Deficient representation + 2) Prejudice. b. Hill v. Lockhart (1985): Test for IAC at plea bargaining stage. i. Objectively Deficient = More than failed strategy. ii. Actual Prejudice = Reasonable probability that but for counsels error, D would NOT have pled guilty and would have insisted on going to trial. iii. Strickland standard almost outcome determinative here: NOT asking whether D would have accepted better plea; D must show passed up winning argument at trial (e.g., counsels failure to inform D that Govts key E at trial was inadmissible). c. Policy: Finality, Judicial economy, Public confidence, Court reluctant to penalize Govt for bad defense lawyering or to evaluate bargain without considering D's actual guilt/innocence, Limited resources, P discretion, Structural capability. Effect of Plea on Prior Constitutional Claims: CANNOT challenge constitutional violation that occurred prior to plea, even if it would have prevented conviction had the case gone to trial. a. Conditional Plea: Allows D to preserve appeal for certain issues and plea guilty. b. May challenge plea procedure, or VKI. c. McMann v. Richardson (1970): Counseled D cant collaterally attack guilty plea on the ground he misjudged admissibility of E. d. EXCEPTION: If claim goes to power of State to bring D into court to answer charge. (e.g., Vindictive prosecution; Double jeopardy). i. If Govt could have cured problem, no recourse. ii. Broce (1989): D pleaded guilty to two charges of conspiracy, while co-Ds charged with only one for same transaction. SCOTUS: Would need findings not in record, so antecedent claim canNOT be heard.

B.

Plea Bargaining (10B): D may challenge VKI of plea, PC for indictment, Vindictiveness of P. 1. Constitutional: (Brady) Judge must accept plea/bargain; plea only rejected if Gov't promises something it cannot legally do. 2. Limitations? a. Bordenkircher v. Hayes (1978): Does P have PC to support indictment? b. Extreme deference to P; Suggests Vindictive P may not be available in PB stage. c. United States v. Pollard (1992): If plea is VKI, P can threaten to prosecute Ds family, etc. as part of PB strategy, so long as P can legally do so. d. Newton v. Rumery (1987): D can waive rights as part of PB, including right to bring 1983 civil rights suit. e. United States v. Mezzanatto (1995): P can force D to waive FREs as part of plea. Plea Bargains as Contracts: Court enforces K against party trying to exploit circumstances. 1. Santobello v. New York (1971): For plea to be VKI = D must get what he is promised in return for guilty plea. a. Facts: D accepts plea preventing P from making recommendation at sentencing, D gets new counsel and moves to withdraw plea (denied), P reneges. b. Plea was not VKI since D relied on bargain, entitled to promise in exchange for 6

C.

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

2.

3.

waiver of rights. c. Court remands to determine remedy, but NOT K law remedy (D doesnt get to pick remedy). Mabry v. Johnson (1984): NO constitutional right to specific performance of plea bargain where plea not yet entered in open court. a. Plea becomes an enforceable agreement only when entered before judge in open court. b. Consideration: P must fulfill a promise that actually induces the plea, upon which D relies to detriment. Ricketts v. Adamson (1987): NO double jeopardy if D agrees in PB to testify against coDs, but refuses to in second trial, and P brings higher charges against D. a. Court likely to enforce plea agreement against party trying to exploit events. b. NOT pure K law!

D.

Policy of Plea Bargaining: D more likely to accept plea the wider the gap between maximum sentence and offered sentence. 1. Historical Context: Three factors led to rise in plea bargaining. a. Lawyerization (post-Gideon): Increased trust among criminal bar because have long-term relationships. b. Judges: Juries are unpredictable, PB is more rational, predictable; All parties can estimate prices on both sides. c. Federal Rules of Evidence: Complicate, slow down trials. 2. Why so prevalent? Systemic constraints on Defense = Overwhelming number of cases end in guilty plea. a. Huge caseload, so pleas make more time for trial worthy cases. b. Structural problems in CJ system make it harder for Ds to show IAC. 3. Benefits of PB a. Without PBs, more trials but fast and sloppy = increased risk of erroneous result. b. Efficient, maximizes choices, bargains out Ds who are clearly guilty. c. Provides D opportunity to minimize punishment, legal expenses and anxiety (average PB sentence is 30-40% lower than maximum USSG sentence). d. Gives P flexibility to structure punishment: Retributively just, Most deterrent, Tailored to rehabilitative needs of offender, Lowest cost in resource allocation. e. Punishment quicker and cheaper, especially where D likely to be convicted. 4. Costs of PB a. P overcharges!!! b. P sets the price (in S.G. regimes, P sets the sentence to some extent, too). c. P = true provider of mandatory minimums. d. Erodes constitutional protections since D has to waive them to plea. e. P's power = leverage over D attorneys. f. Convicting innocents: Innocent Ds plead guilty, undermine reliability of system. g. Hawks dont like it: Ds get off easy. h. D attorneys have incentives to plead: Huge workload, cherry-pick cases for trial.

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

VI.

A.

DISCOVERY AND DISCLOSURE: While NO general constitutional right to discovery in criminal

case, the Due Process Clauses of 5th and 14th As require Gov't to provide certain E to Defense. Disclosure by the Government [11A] 1. Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 16. Discovery and Inspection: Ps must hand over certain kinds of evidence on request. a. Discoverable i. D's Statements: Oral, written or recorded. ii. D's prior criminal record. iii. Documents/objects: Material to Defense, Govt uses in case-in-chief, Belonging to D, Results from exams/tests, Expert witness reports. b. NOT Discoverable i. Work Product: Mental or legal strategy. ii. Statements by Gov't Ws (Jencks Act 3500: After W testifies, for safety). iii. Non-testifying Gov't Expert W reports. iv. Police Reports (otherwise would be purposely minimal). c. UNCLEAR whether Discoverable i. Inadmissible E. ii. Wood v. Bartholomew (1995): Polygraph tests not discoverable. iii. SCOTUS hasnt decided whether inadmissible E disclosed under Brady. 2. P's Constitutional Disclosure Obligations a. Brady v. Maryland (1963): Suppression by P of E favorable to accused violates DP where E is material to guilt or punishment; Both if good/bad faith. b. REMEDY for Brady violation = New trial. c. Is E favorable to the accused? Credibility E, physical E, impeachment. d. What constitutes suppression? i. If Govt (including ANY Govt agency) has E and not discoverable to D (even if P not aware it exists). ii. P has no duty to seek out exculpatory E, and D need NOT request E. e. When is E material? i. Prejudice = Reasonable probability that RESULT would have been different with E (Kyles v. Whitley, 1995). ii. NOT that D would have been acquitted, but if all E as a whole. iii. Reasonable probability = Less than preponderance of the evidence. f. Brady applies to sentencing, too! Disclosure by the Defense [11B] 1. Rule 16: P and D share reciprocal discovery rights. a. DP silent on discovery, but supports reciprocal discovery rule. b. Goal NOT to protect D, or else D would not have to reciprocate. c. If D requests discovery from P, D must make available to P: i. Docs/objects in possession or control to be used in D's case-in-chief. ii. Reports of tests or exams in possession/control used in D's case-in-chief. iii. Expert reports, summary of expert W testimony. 2. Rule 12: D must always turn over expert W report summary if raising mental 8

B.

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

3.

4.

5.

capacity or other mental conditions. Fifth Amendment Self-incrimination Protection: Incrimination narrowly construed as only what happens on the stand. a. Privilege designed to protect D from having to either confess or lie. b. Key Question: Does D have an alternative to confessing or lying? c. Schmerber Drunk driver BAC test not incrimination since D not forced to lie. d. Williams v. Florida (1970): Rule requiring disclosure of alibi witnesses OK, because D not forced to call them; rule just accelerated disclosure of Ws. Sixth Amendment Compulsory Process Clause a. What sanction is appropriate for D who violates the discovery rule? b. Taylor v. Illinois (1988): Seeking tactical advantage by willful misconduct made preclusion of DW appropriate, even if Ds attorney, and not D, is at fault. Rules and ABA Standards a. D must give notice of alibi and insanity defenses. b. Federal Rules: Reciprocal discovery of tests c. ABA: W names and statements unconditionally required to be disclosed.

VII.

A.

THE JURY

The Right to a Trial by Jury [12A]: 6th A. right to jury trial attaches if statutory maximum sentence is greater than 6 months imprisonment. 1. Why Juries? a. Shield from Govt oppression. b. History: English judge decided matters in colonies, jury was LOCAL. c. Protects D from Legislature: Baseless crimes, jury nullification. d. Protects D from Judiciary: Biased, tools of Govt, elitist. e. Protects D from Executive: Overzealous Ps. f. 12 jurors vs. 1 judge: More factfinders, more reliable, better chance that at least one will relate to D. 2. Problems with Juries a. May not grasp complicated, technical issues. b. Need to keep certain E away from jury because prejudicial, not probative, etc. 3. When does D have Right to Jury Trial? a. Duncan v. Louisiana (1968): NOT for petty crimes, only where statutory maximum sentence is greater than 6 months imprisonment. b. Presumption for 6 months or less: Jury not required unless there are additional statutory penalties so severe as to indicate that the legislature considered the offense serious. (Louis v. United States) c. No Aggregating sentences: Separate punishments UNLESS crime has no statutory maximum, then actual punishment imposed. 4. How many jurors are required? At least 6. a. Ballew v. Georgia (1978): 5 member jury unconstitutional; 12 is best, but 6 OK. b. Policy i. Effective group discussion more likely, Group-think less likely. 9

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

5. 6.

ii. More issues vetted, more perspectives, more facts remembered. iii. Smaller the jury, more Ds convicted; Larger the jury, more Ds acquitted. iv. Larger juries are more diverse (racial, class, etc.). Non-Unanimous Juries a. 6th A. incorporated to states, BUT unanimity NOT required for States. b. Burch v. Louisiana (1972): If only 6 jurors, unanimity IS required. Jury Nullification a. General verdict: Ask only whether D is guilty of crime, not for certain facts. b. Jury could Acquit on any number of findings: i. P didnt prove an element BARD. ii. W wasnt credible. iii. Jury doesnt agree with the law = Nullification. c. Right to Nullify? i. Defense attorneys CANNOT argue nullification to jury. ii. No nullification instruction. d. Jury Nullification and Race i. Necessary response to racially discriminatory CJ system. ii. Crack/Cocaine sentencing disparity.

B.

Jury Composition [12B]: Jury venire must be drawn from fair cross section; Individual jurors may be excluded for cause (e.g., biased) OR with peremptory challenges (with limits); D must make PF case to raise either. 1. Venire (the jury panel): No need to be representative of community, but must be drawn from fair cross section of community. a. Duren v. Missouri (1975): Venire where women could opt out unconstitutional because opt-out was allowed solely on basis of gender. b. D must make Prima Facie case for violation of fair cross section: i. Alleged exclusion affects a distinctive group: D need not be a member, Group has immutable characteristics (excluding ideological groups doesn't create barrier to impartial verdicts or presumption of unfairness), Lower courts use protected classes from E/P jurisprudence. ii. Underrepresentation of group (unreasonable in proportion to community at large). iii. Which results from systematic exclusion: NO discriminatory intent! c. If D makes prima facie case, Gov't must show its system manifestly and primarily advances a state interest. 2. Voir Dire: First 6-12 jurors questioned. a. For Cause Strike/Challenge: If either side believes a venireperson is partial. b. Partiality: Those strong and deep impressions which close the mind against the testimony that may be offered in opposition to them, which will combat that testimony and resist its force, that constitute a sufficient objection. (Reynolds) i. Wainwright v. Witt: Only if views about case are strong enough to prevent or substantially impair the performance of her duties as a juror. ii. Prospective jurors need not be completely uninformed about the case or completely without opinions. 10

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

c.

3.

Local rules also provide additional for cause challenges (e.g., ill health, financial hardship, etc.). d. Ham v. South Carolina (1973): Where special circumstances, MUST be able to Q panel about racial biases. i. Trial involves allegations of racial or ethnic prejudice, OR ii. Capital case where allegation of an interracial crime (i.e. D and V are different races) (Turner v. Murray); but ONLY if capital case (Ristaino). iii: Why? Death is different (i.e. special risk of improper sentencing since interracial crime + broad discretion given to jury in sentencing. e. Death Qualifying the Jury: May NOT exclude juror for cause based on attitude about DP. i. UNLESS the views would prevent or substantially impair the performance of her duties as a juror. ii. Lockhart v. McCree (1986): If juror would never vote to impose death penalty, removable for cause in capital case. iii. In practice, jury balance tips toward death (jurors who always impose DP stay, but those who never do are excluded); also tips toward finding guilt. Peremptory Challenge: Attorney excuses juror for any reason without explanation. a. Limited number available to each side (per local rule or judge). b. Purpose of Peremptory Challenges i. Back-up to challenges for cause. ii. Gives parties opportunity to participate in construction of decisionmaking body, thereby enlisting their confidence in the decision. iii. Allows parties to act on the core of truth in most common stereotypes. c. Batson v. Kentucky (1986): E/P forbids preemptory strikes based solely on race; Also applies to gender, unequal Q during voire dire of one race/gender. d. Batson Procedure (for both P and D, criminal and civil) i. D must make PF case sufficient to raise inference that P exercised peremptory challenges to exclude jurors based on race (pattern). ii. Then P must give race/gender neutral reason for strike (most any reason, e.g., long, curly, unkempt hair is valid, race-neutral reason). iii. Court determines if strike constituted purposeful discrimination. iv. Difficult standard that approaches cause, but effectively protects against structural discrimination.

C.

Influences upon the Jury [12C]: Extreme deference to trial judge in way it handles publicity and its impact upon the jury; Standard of review is Impartiality. 1. Publicity: If unusual level of pretrial publicity, may threaten juror impartiality so constitutional duty to Q jury about publicity. (Irvin v. Dowd). a. For cause challenges if wave of public passion or assertions that jurors cannot be impartial. b. Mu'Min v. Virginia (1991): Substantial publicity but jurors said they could be impartial, so NO error where trial court disallowed detailed Qs about publicity. i. No DP/6th A. violation; D guaranteed only a fair and impartial trial (judge's slight impartiality investigation does not itself render trial 11

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

2.

unconstitutionally defective). ii. DISSENT (Marshall): When a prospective juror has been exposed to prejudicial pretrial publicity, a trial court cannot realistically assess the jurors impartiality without first establishing what the juror already has learned about the case. iii. Balancing test: Ds interest in an impartial jury vs. Courts interest in selecting jury in reasonable way. iv. Review = Extreme deference to trial court in managing trial. Improper Prosecutorial Argument: Even if P argument improper, Court will only reverse on DP grounds where Ps argument rendered trial fundamentally unfair. a. Improper: P asks jury to base decision on illegal ground (i.e., something other than factual guilt on each element BARD). b. Potential Defense: If D attorney invited Ps improper argument. c. Darden v. Wainwright (1986): DP violation only if trial fundamentally unfair. i. Was P's argument inappropriate (asked jury to make decision on improper ground)? ii. If yes, did argument render the trial fundamentally unfair? iii. Here, no: Some objectionable content in response to Ds argument, strong weight of E against D, D strategy not to present any Ws besides D. iv. Deference to trial court: Floodgates, Uncertainty, Bright-line rules impossible, Trial judges best suited to gauge impact on jury, etc.).

VIII. THE CRIMINAL TRIAL

A. The Unconstitutional Burden Doctrine [12D]: Gov't/Court CANNOT rely upon Ds invocation of constitutional rights as evidence of Ds guilt. 1. United States v. Jackson (1968): Statute that gave maximum sentence of death if D convicted by jury, but life imprisonment if D convicted at bench trial unconstitutional. 2. Why? It needlessly encouraged waivers of constitutional rights to jury trial and to remain silent. The Defendant's Right to Be Present [12D]: 6th A. right only extends to critical stages where Ds presence contributes to fairness of procedure. BUT great deference to trial court's discretion in particular circumstances (especially safety/trial management reasons). 1. Portuondo v. Agard (2000): NO 6th A. violation for P to call jurys attention to fact that D heard all Ws testify and could tailor testimony accordingly. 2. Illinois v. Allen (1970): Trial judges confronted with disruptive, willfully disobedient, stubbornly defiant Ds must be given sufficient case-by-case discretion. a. Three possible remedies for unruly Ds: i. Bind and gag D. ii. Hold D in contempt of court. iii. Remove D from courtroom until agrees to behave. 3. Taylor v. United States (1973): Voluntary absence from trial NOT effective waiver of 6th A. right UNLESS D given notice that failure appear would result in waiver. 12

B.

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

4.

5.

Holbrook v. Flynn (1986): No DP violation when D surrounded by security officers and state troopers in the courtroom. a. Distinguished from right not to wear prison clothes before jury (a constant reminder of accuseds condition that may affect a jurys judgment). Kentucky v. Stincer (1987): DP protection limited to any stage of criminal proceeding critical to its outcome if Ds presence would contribute to fairness of procedure. a. W competency hearing NOT a critical stage.

C.

The Defendant's Right to Testify [12D]: Cannot use Ds refusal to testify against him (i.e. P or court cannot argue that Ds silence or failure to deny or explain fact within Ds knowledge indicates truth of Ps case). 1. Griffin v. California (1965): Any comment about Ds silence violates the 6th A. and 5th A. Self-Incrimination Clause because it's a penalty imposed by courts for exercising a constitutional privilege. a. Mitchell v. United States (1999): Judge at sentencing, I held it against you today that you didnt come forward today and tell me that you really only did this a couple of times violated the 5th A. b. DISSENT (Scalia): Harsh criticism of Griffin doctrine. 2. Doyle v. Ohio (1976): Ds post-arrest silence after Miranda warning cannot be used against D in Ps case-in-chief. The Defendant's Right to Obtain Evidence (Prohibition of Destruction of Evidence) [12D]: Unless materially exculpatory, Gov't may dispose of E as long as it acts in good faith. 1. Arizona v. Youngblood (1988): While Gov't must disclose material exculpatory E to D (Brady), Gov't only has duty to act in good faith in retaining evidentiary material that could exculpate D if D had chance to test it (bad faith required for constitutional violation for disposing of E that is NOT materially exculpatory). 2. California v. Trombetta (1984): Court refused to suppress results of BAC test even though Gov't failed to preserve breath samples used in the test. The Defendant's Right to Confront His Accusers [12D]: If statement is testimonial, cross examination required in order to satisfy 5th A. Confrontation Clause. 1. Physical screen blocking W OK for good cause if physical appearance irrelevant. 2. Out-of-court statements historically handled through FREs on hearsay. 3. Before Crawford, hearsay rules were equivalent to the Confrontation Clause (i.e. out of court statements tested for reliability; reliability established through hearsay exception). 4. Crawford v. Washington (2004): If statement is testimonial, D has right to cross-exam. a. Crawford applies regardless of whether statement is reliable. b. Dying declarations NOT subject to Crawford. 5. Davis v. Washington (2006) a. Testimonial: Statement intended for use in future criminal prosecution. b. W identified her assailant to 911 operator, provided info intending to help the police resolve an "ongoing emergency," NOT to testify to a past crime. c. Why? Under the circumstances, W was not acting as a "witness," and the 911 transcript was not "testimony." 13

D.

E.

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

6. 7. 8. 9.

d. Thus, Sixth A. does not require her to appear at trial and be cross-examined. Emergency: Statements are non-testimonial if limited to Ws present-sense impression; Once emergency ceases, statements become testimonial. Hammon v. Indiana: If Ws statements used to accuse in some way after the fact (e.g., ID license plate as it drives away), it's testimonial (DV porch statement). Malendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts: Technician must be available for cross-exam in order to introduce scientific evidence. Gray v. Maryland (1998): 2 co-Ds, D1 confessed pre-trial. Can D1s confession be used against D1 where D1 will not testify? a. NO, unless D1 testifies. b. What if D2s name is redacted from the confession? No difference. c. Solution? Literally delete all references to D2. Jury won't know. d. DISSENT (Scalia): Disagrees with solution grammar of confession warped.

IX.

A.

RIGHT TO COUNSEL: If D is sentenced to imprisonment, D has right to trial counsel and counsel

for first appeal of right. 6th Amendment: In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right . . . to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defense. 1. Why is Counsel so critical? a. Technical legal expertise (e.g., complexity of evidence law). b. Strategic knowledge. c. Gov't resources against individual (weight of proceeding: life/liberty at stake). d. When people can afford counsel, they do. Evolution of the Right to Counsel: In capital cases, federal law required appointment of counsel for indigent Ds, and many states followed. 1. Powell v. Alabama (1932): In capital cases, 14th A. DP violated if D does not have right to effective assistance of counsel in State prosecution. a. Limited to cases where D is incapable adequately of making his own defense due to ignorance, feeble-mindedness, illiteracy or like = special circumstances. b. Racial tensions, mob atmosphere can also meet special circumstances test. 2. Hamilton v. Alabama (1961): Appointment of counsel required for every capital case in State court, not just in special circumstances. 3. Betts v. Brady (1942): Appointment of counsel for non-capital cases in State court required only when the absence of counsel would result in a trial. . .offensive to the common and fundamental ideas of fairness and right. Reaffirms special circumstances. 4. Johnson v. Zerbst (1938): 6th A. requires appointment of counsel in noncapital Federal cases. Reaffirms special circumstances test. 5. Gideon v. Wainwright (1963): Right to counsel = fundamental right, essential to a fair trial. Incorporated into 14th A. DP and thus applicable to states. a. Overrules Betts no more special circumstances test. b. Every post-Betts case presented special circumstances, wasnt being enforced. c. Right to counsel is a necessity, not a luxury; people who can afford attorneys 14

B.

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

d. e. C.

attempt to get the best, Govt hires best Ps possible, Indigent Ds disadvantaged. Concurrence (Clark): No distinction between DP for capital, non-capital cases. Gideon increases systemic pressure on plea bargaining scheme: Trials become slower and more expensive, D attorney salaries from judiciary.

Scope of Right to Counsel: If not given attorney, D cannot be sentenced to incarceration. 1. Argersinger v. Hamlin (1972): If imprisonment is possible sentence, counsel required. 2. Scott v. Illinois (1979): If actual imprisonment is imposed, counsel required; No right where D is fined for charged crime but not sentenced to a term of imprisonment. 3. Baldasar v. Illinois (1980) (OVERRULED): Conviction where no right to counsel attached CANNOT trigger sentence enhancement for second conviction (statute at issue converted a second conviction for misdemeanor into felony with enhanced punishment). 4. Nichols v. United States (1994): Overrules Baldasar; Uncounseled convictions CAN be used to enhance convictions for subsequent crime. 5. Alabama v. Shelton (2002): Suspended sentence that may lead to actual deprivation of a persons liberty may not be imposed without appointed D attorney. a. DISSENT (Scalia): D has not, and may never, suffered deprivation of liberty. The Right to Counsel on Appeal 1. Griffin v. Illinois (1956): Pre-Gideon; Statute denying free trial transcripts to indigent Ds where it is necessary to appeal is unconstitutional. a. The Constitution prohibits a state from structuring an appellate process that has the effect of denying an effective review to indigents while permitting it to those with financial means. b. There can be no equal justice when the kind of trial a man gets depends on the amount of money he has. 2. Douglas v. California (1963): (companion to Gideon) Ds have right to assistance of counsel for first appeal of right. a. Why? Equality vs. Fundamental Fairness. b. Fairness = Rational level of Govt behavior every person is entitled to (DP). c. Equality = Similarly situated parties get the same treatment (E/P). d. Since impossible to police equality in CJ, fairness becomes the standard. 3. Draper v. Washington (1963): Indigent D entitled to free transcript regardless of whether the appeal is frivolous. 4. Ross v. Moffitt (1974): No assistance of counsel required beyond first appeal of right (i.e. in discretionary appeals up to SCOTUS). a. DP does not require appointment of appellate counsel at all. b. Why? Trial and appeal are different: Determine Ds guilt vs. Overturn a finding of guilt made by judge or jury . c. McKane v. Durston (1894): DP does not even require state to provide an appeal. d. E/P satisfied if counsel provided to indigent D for first appeal of right, but not for further discretionary appeals. e. E/P does not require equality, only that state appellate system be free of unreasoned distinctions AND indigents must have adequate opportunity to present claims within the adversary system. 15

D.

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

f.

5. 6. 7. 8.

9. E.

The state cannot adopt procedures which leave an indigent D entirely cut off from any appeal at all or extend to such indigent Ds merely a meaningless ritual while others in better economic circumstances have a meaningful appeal. g. D can file same brief once the attorney has spotted the issues for appeal, OR Appeal of right corrects error, Discretionary review fixes doctrine. h. DISSENT: No logical difference between appeals of right and permissive review. Evitts v. Lucy (1985): Right to effective assistance of counsel at first appeal of right. United States v. MacCollom (1976): Rule requiring judge to certify that 2255 habeas was non-frivolous before D gets free trial transcript OK. Mayer v. City of Chicago (1971): State must provide indigent D a record of sufficient completeness to permit proper consideration of claims on appeal, even though such a record is NOT a condition precedent for appeal. MLB v. SLJ (1996): Unconstitutional to prohibit mothers appeal of parental rights termination where she cannot pay admin fees required by Mississippi statute. a. No debtors prison: Cannot imprison someone for inability to pay fines. b. If fined but not paid (willing only), still under sentence and could bear on sentencing in later conviction (Beardon v. Georgia). Beardon v. Georgia: State can sentence D to prison or compulsory labor for failure to pay fines ONLY if (1) prison originally an option and (2) failure to pay was willing.

Critical Stages of the Proceeding 1. Coleman v. Alabama (1970): Right to counsel applies at every critical stage of a criminal prosecution. 2. Right attaches when adversary judicial proceedings have begun (initial appearance or any formal charging process like filing of Indictment or Information, whichever occurs first) and continues throughout sentencing. 3. What constitutes a Critical Stage? a. Preliminary hearing (Coleman). b. Initial appearance (Brewer v. Williams, 1977). c. Arraignment (Hamilton v. Alabama, 1961). d. Any informal meeting between D and Gov't that is designed or likely to elicit incriminating E from D. 4. NOT a Critical Stage: a. Ex parte proceedings that don't adversely affect Ds rights (e.g., warrant). b. 6th A. NOT applicable after sentencing, but DP could afford protections. c. Morrissey v. Brewer (1972): Parole revocation NOT part of criminal P, but DP does mandate procedural protections. d. Wolff v. McDonnell (1974): Prisoner has a right to be heard in prison disciplinary hearings that could adversely affect his liberty interests, but not necessarily with the assistance of counsel. e. United States v. Gouveia (1984): No counsel needed for inmates placed in administrative segregation as a result of crimes committed while incarcerated, UNLESS adversary judicial proceedings are initiated against the inmate. f. NO right to counsel in habeas corpus/collateral attack proceedings. i. Penn. v. Finley (1987): 6th A. right NOT available on habeas. 16

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

5.

Murray v. Giarratano (1989): NO DP right to counsel or access to courts theory in habeas. Parole/Probation Revocation a. Gagnon v. Scarpelli (1973): Right to counsel required at parole/probation revocation proceeding where a sentence is not imposed at the hearing and special circumstances exist. b. Special Circumstances: Probationer/parolee requests counsel based on timely and colorable claim that: i. Not committed the alleged violation of conditions upon which she is at liberty; OR ii. Even if violation is uncontested, there are substantial reasons which justified or mitigated the violation and make revocation inappropriate, and the reasons are complex or otherwise difficult to develop or present.

ii.

F.

Effective Assistance of Counsel [3B1]: Strickland IAC test: (1) was counsel Objectively Deficient + (2) was D Prejudiced? 1. 6th A. Right to Effective Assistance: No effective in 6th A., but mockery otherwise. a. ONLY guaranteed where Gov't must provide attorney. b. Protections to Ensure that Effective Assistance is Obtained: i. Geders v. United States (1976): Attorney must be able to confer with client during overnight recess that falls between direct and cross-exam. ii. Herring v. New York (1975): Attorney has right to give a closing summation in a bench trial. iii. Ferguson v. Georgia (1961): Gov't may not prohibit D attorney from eliciting Ds testimony on direct examination. iv. Brooks v. Tennessee (1972): Gov't may not restrict attorneys choice for when to put D on the stand. c. LIMITS do exist: i. Perry v. Leeke (1989): No error where trial court ordered D not to consult with attorney during 15-minute recess that followed his direct exam and proceeded the Gov'ts cross-exam. 2. Strickland v. Washington (1984) For IAC D must show that counsel's performance was a. Objectively Deficient (In the circumstances, at the time, was it reasonable for attorney to have made particular choice?), AND i. Show that counsel made errors so serious, did not function as counsel guaranteed by 6th A. ii. Duties required of counsel (non-exhaustive): Loyalty, Conflict-free, Advocate Ds cause, Consult D on important decisions, Apprise D of important developments, Bear such skill and knowledge as will render trial reliable and adversarial, iii. Evaluates totality of the circumstances: Norms of practice are guides, Judicial scrutiny of counsels performance highly deferential. b. Prejudiced D (Was there reasonable probability that but for counsels unprofessional errors, result of proceeding would have been different? i. Reasonable probability = Enough to undermine confidence in result. 17

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

ii.

c.

d.

Prejudice inferred in some contexts: Actual or constructive denial of counsel, Gov't interference with counsels assistance, Conflict of interest. iii. D must affirmatively prove prejudice: More than some conceivable effect but less than preponderance (not same as newly discovered E standard). iv. Court presumes that judge and jury acted according to the law (absent challenge to judgment on grounds of evidentiary insufficiency). Guide to Application of Strickland: i. Not mechanical rules, can apply prongs in any order. ii. Focus on fundamental fairness of the trial/adversarial proceeding. iii. Applies to direct review, PCR and HC. iv. Ineffectiveness = Mixed Q of law and fact. Rompilla v. Beard (2005): Effectiveness requirement ensures a fair trial. The benchmark for judging any claim of ineffectiveness must be whether counsels conduct so undermined the proper functioning of the adversarial process that the trial cannot be relied on as having produced a just result.

G.

Defendant's Right to Proceed Pro Se: D can represent herself if waiver of counsel in K+I. 1. Faretta v. California (1975): D can represent herself if waiver of right to counsel is knowing and intelligent. a. Right to self-representation implied in 6th A, liberty/dignity interest in making choice outweighs bad decision. b. History: Statutory + English law + Founders. 2. Competency to Waive: Same standard to stand trial, whether D has sufficient present ability to consult lawyer with a reasonable degree of rational understanding, and has a rational and factual understanding of the proceedings. 3. Standby Counsel: After waiver, appointed counsel remains available through trial to serve as Ds resource or to take over if D chooses. 4. Hybrid Representation: D represents self pro se + appointed counsel is co-counsel. a. McKaskle v. Wiggins (1984) Faretta does NOT require hybrid representation, but hybrid representation is constitutional. b. Standby/hybrid counsel does NOT violate Ds right to self-representation. c. Efficiency and efficacy are important (per Faretta dissent). d. Standby/hybrid counsel can violate Ds right to self-representation: Did D have a fair chance to present his case in his own way? i. Pro se D entitled to preserve actual control over the case he chooses to present to the jury. ii. Participation by standby counsel without Ds consent may not destroy the jurys perception that D is representing himself. iii. NO issue if appointed counsel never addresses jury or D in front of jury. 5. Judicial Discretion: Judges have right and power to deny Faretta motion if D intends to delay or disrupt trial. 6. Remedy for Faretta Violation: New trial, No harmless error review (cannot assess how D would have done with counsel). 7. Right to Represent Self on Appeal a. Martinez v. California (2000): Counsel required, no right to appeal pro se. 18

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

b.

8.

Jones v. Barnes (1983): Counsel determines which arguments are raised on appeal; Counsel does NOT have a constitutional duty to raise every nonfrivolous issue requested by D. c. Consistent with Faretta? Yes, trial level different because involuntary; Appeal invoked by D, so liberty interest less critical, turns on efficiency/efficacy invoked in Faretta dissent. d. Anders v. California (1967): If counsel finds no appealable issues, must file brief attesting she reviewed record and found no meritorious claims and request to be withdrawn from the case. i. BUT attorney should identify possible issues to assist appellate court. ii. Cannot file no appeal (duty of loyalty); Cannot file frivolous brief. e. Smith v. Robbins (2000): Narrows Anders. i. Shifts some burden to courts from attorneys. ii. Lawyer must summarize history of case, attest to review of record with client, and advise client of right to file supplemental brief, and ask court to review record. If D Chooses NOT to Proceed Pro Se: May only decide whether to accept plea agreement or go to trial and whether to testify.

X.

A.

DOUBLE JEOPARDY [14 A-D]: If D is (1) twice put in jeopardy for the (2) same offense, Gov't

cannot retry (or appeal). Points to Keep in Mind 1. Applies only to criminal cases (fuzzy when cases are in-between civil and criminal, such as in traffic court or mental issues). 2. When does Jeopardy attach? 3. Violation occurs when D prosecuted for same offense more than once, also protects D from being punished for the same offense twice. 5th Amendment: Nor shall anyone be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb. 1. Two parts: (1) same offense + (2) twice put in jeopardy. 2. Why DJ? Functional protection. If D had to defend case again and again, D would eventually lose. 3. Scope of 5th A. Protection: Bars retrial/appeal in some situations. Twice in Jeopardy 1. Pretrial: If before jury empaneled, charges are dismissed, but CAN be retried (Surfess). 2. Jeopardy Attaches: Once jury empaneled, or in bench trial when first W sworn. 3. Motion to Dismiss: If basis for dismissal is a. Unrelated to guilt/innocence (e.g., suppression): CAN be retried. b. Related to guilt/innocence: NO retrial (since like an acquittal). 4. Mistrial a. Upon Ds Request: CAN be retried UNLESS D can show that P goaded her into 19

B.

C.

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

5.

6.

7.

8.

9. D.

asking for mistrial (e.g., P sees case not going well and provokes D into asking for mistrial) (Kennedy). b. Not upon Ds request: CAN be retried IF judge finds manifest necessity for retrial) (Perez, Kennedy). Jury Acquittal: NO retrial AND P cannot appeal a jury acquittal (Fong Foo). a. Includes implied acquittals where D acquitted of lesser-included offense, it implies acquittal of greater offense (Reem). b. Doesnt matter how wrong the acquittal (unless judge sets aside jury verdict), because must protect JN. Jury Conviction: D can appeal and Ps appeal limited (e.g., lesser-included offenses). a. If trial judge sets aside verdict as matter of law: P can appeal the verdict. b. If D's appeal wins, DJ bars new trial IF grounds for reversal was insufficiency of the evidence (tantamount to acquittal) (Ball). Why Allow P to Retry D? a. Fear that appellate court would consider consequences of reversing conviction (acquittal) in decisions about procedural/substantive protections. b. Inconsistency due to result-oriented judging, and fewer pro-D rulings. Collateral Estoppel a. Ashe v. Swenson (1970): D acquitted, then P brings second set of charges involving different Vs from same factual situation. b. Why CE? Dont want courts/litigants to waste time re-litigating Qs of fact that are already decided by a fact-finder. c. Not exactly DJ, but DJ contains a CE doctrine implicitly that prevents P from retrying facts that have been found conclusively in an earlier case. d. Applies to sentencing enhancement part of trial. If D can show that judge was bribed, maybe prove that D was not actually in jeopardy, so DJ right never attached (but not definite rule).

Same offense 1. Why? a. So Govt can't split counts of same conduct into multiple trials to get around DJ. b. Protects Ds from having to keep defending against same charge, gives repose. c. Protects Ds from facing potential for increased punishment until P gets the sentence she wants. d. Law is complicated, in part because of plurality opinions, and rules dont seem to embrace a unified theory. 2. Blockburger v. United States (1932): When do two statutes constitute the same offense for DJ purposes? a. Does each provision require proof of fact that the other does not? b. E.g., Crime 1 requires proof of A, B, C; Crime 2 requires A, B, Z. NO DJ because C + Z are each not found in the other. c. Lesser-included offenses are NOT separate offenses: A, B vs. A, B, C are the same under Blockburger. 3. Ohio v. Brown (1977): D stole car on 11/29, car discovered on 12/8, D charged with joyriding on 11/29 and auto theft on 12/8. 20

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

a. b. 4.

5.

6.

7.

Same offense, so DJ attaches, even though indictment invokes different date. Leaves open problem where legislature makes crime on X date different from crime on Y date. Harris v. Oklahoma (1977): D convicted of felony murder that occurred during robbery, D brought to trial for robbery with a firearm based on same events. a. Same offense, so DJ attaches. Conviction for greater crime (felony murder) required conviction for lesser crime (robbery with a firearm). b. Blockburger issue since felony murder statute included a list (not robbery only). c. Listing Crimes: Crime with predicate that can be true of list of options (e.g., x murder, where x = felony, aggravated, etc.). d. If in order to prove felony murder P must prove a listed item, that item is a greater-included offense than the actual item on the list by itself. Super Crimes: Pattern with a list (e.g., RICO list offenses, but pattern is what makes the offense a super crime; pattern requires at least two acts). a. D can be charged with RICO and with list item itself IF pattern is different than proving actual underlying offense itself. Grady v. Corbin (1990): [Maybe overruled by Dixon] (DUI lab mixup): Crimes from same transaction cannot be retried under DJ. a. CE bars trial (not under BB since different elements in each) because conduct to be proven is the same. b. Court moves from looking at elements (as in BB) to D's conduct. c. Just result? Gov't operating under BB rule, Punishments very different, Not trying to get second bite at the apple. d. Good rule? Effect of same conduct rule forces P to bring any possible charge in indictment because could forfeit later if same transaction. e. Does it matter in world of PB? P wants to charge kitchen sink from the start, BUT impacts could hurt D. United States v. Dixon (1993): D charged with homicide, out on bail on condition that D not commit any more crimes. P brings drug charges at bail contempt hearing. a. No BB problem: Drug crime has different elements than contempt. b. But Grady would bar! Overrule Grady? c. 5 votes say yes, Grady should be overruled. d. BUT, 5 votes say that Dixon should win because still DJ (some of the overrule Grady justices see Ds case as a list crime problem like Harris). e. Complete Breakdown: Extremely difficult to predict where SCOTUS will go; no coherent theory underlying the rule.

XI.

A.

SENTENCING [13C]

Sentencing Considerations 1. Past Criminal Conduct a. YES, generally can be considered. b. United States v. Tucker (1972): BUT prior felony convictions where counsel was not appointed may NOT be considered. 21

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

c. 2. 3. 4. 5.

6.

7.

Nichols v. United States (1994): BUT prior misdemeanor convictions where D had no right to counsel may be considered at sentencing. Future Dangerousness: YES, psychiatric testimony about Ds future dangerousness may be considered at sentencing, even in death case. Barefoot v. Estelle (1983). False Testimony at Trial: YES, and does not place an unconstitutional burden on Ds right to testify at trial. Silence at Sentencing: NO, would violate Ds 5th A. privilege against selfincrimination, even if D pleaded guilty. Mitchell v. United States (1999). Racial Bias a. Barclay v. Florida (1983): Fact that D was motivated during offense, YES. b. Dawson v. Delaware (1992): Ds abstract beliefs, including membership in a racist group, NO because protected by 1st A. UNLESS directly relevant to the sentencing proceeding. Judicial Vindictiveness: Ds sentence may NOT be increased after retrial simply because D chose to challenge conviction by means of appeal, PCR or HC. a. North Carolina v. Pearce (1969): To protect D from judicial vindictiveness, trial judge who imposes harsher sentence at retrial must set forth on the record the legitimate reasons for doing so. i. Colten v. Kentucky (1972): Pearce NOT applicable to resentencing after a challenge to a misdemeanor conviction. ii. Chaffin v. Stynchcombe (1973): Pearce NOT applicable to resentencing by a second jury in a case involving jury sentencing. iii. Alabama v. Smith (1989): Pearce NOT applicable to resentencing by trial judge after vacation of a guilty plea. iv. Why? These circumstances don't warrant an inference of vindictiveness. b. Wasman v. United States (1984): Legit reasons could include info about Ds conduct at time of first sentencing hearing or other info not subject to judicial manipulation (e.g., D was later convicted on charges pending at first sentencing). Victim Impact Statements: YES, even in death cases, UNLESS statements are more prejudicial than probative under the evidence rules or unless violate DP Clause. a. Payne v. Tennessee (1991): In death case, VIS may NOT include opinions from survivors about whether D should receive the death penalty.

B.

Cruel and Unusual Punishment: Death penalty limited to intentional or felony murders; In non-death cases: Is sentence extreme in comparison to severity of crime (threshold analysis from Harmelin, but also see Solem factors)? 1. Capital Punishment: SCOTUS says that death penalty itself is not cruel and unusual, so bright line solves proportionality issue. a. Furman v. Georgia (1972): Open-ended discretion (where jury has little guidance on whether to impose death) is cruel and unusual since it tends to produce arbitrary, capricious and often discriminatory results. i. All pre-Furman death sentences reversed. ii. Post-Furman: Statutes guide death sentencing phase with lists of aggravating and mitigating circumstances. b. Lockett v. Ohio (1978): 8th A. requires all relevant mitigating E to be 22

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

2.

considered by a jury (not limited to statutory list). c. Coker v. Georgia (1977): No death penalty for rape. d. Tison v. Arizona (1977): Death penalty essentially limited to intentional or felony murders where D exhibited a reckless disregard for human life. e. Atkins v. Virginia (2002): No death penalty for Ds with intellectual disabilities. f. Roper v. Simmons (2005): No death penalty for juveniles. Non-Capital Punishment a. Graham v. Florida (2010): Life without parole too harsh for teenage Ds. b. Rummel v. Estelle (1980): D stole $120, two prior fraud convictions ($80,826), sentenced to life imprisonment. i. NOT cruel and unusual (5-4). ii. State's interest in recidivism justifies dealing with recidivists harshly. c. Hutto v. Davis (1982): Marijuana possession and distribution, no criminal history, sentenced to two consecutive 20-year terms. NOT cruel, unusual (6-3). d. Solem v. Helm (1983): D forged $100 check, six priors, sentenced to life without possibility of parole. i. Unconstitutional because cruel and unusual (5-4). ii. Cruel and unusual? Three factors: 1) Harshness of offense vs. Harshness of penalty. 2) Sentences imposed for other crimes in same jurisdiction. 3) Sentences imposed for same crime in other jurisdictions. e. Harmelin v. Michigan (1991): Possession of cocaine, no priors, sentenced to life without possibility of parole. i. NOT cruel and unusual (5 (2+3) - 4) (2 say no proportionality analysis). ii. TEST: Keep Solem proportionality test, but first factor is threshold. iii. Factors in favor of Gov't: Deference to legislature on sentences, Legislature checked by political process, Not Courts role to favor one theory of punishment (retribution, rehabilitation, deterrence, incapacitation). f. Ewing v. California (2003): Ds third strike from stealing golf clubs worth $1,200; Law allowed to charge D with either misdemeanor or felony, and court chose felony; Sentenced to 25 years to life. i. NOT cruel and unusual (5-4). ii. Defers to states interest in targeting recidivism. iii. TEST: Is sentence extreme in proportion to severity of crime (threshold analysis from Harmelin)? iv. Why? Deference to legislature, federalism (police power = state right). v. Outcome: Shifts proportionality analysis in favor of state. vi. Concurrence (Scalia): Proportionality analysis impossible. Court simply making policy decisions.

C.

Sentencing Regimes and Apprendi-Blakely: Post-Booker, the Guidelines are strongly advisory and therefore do not need to comply with Apprendi. 1. Constitutional Limitations on Sentencing Procedures a. Rights that Apply at Sentencing: Trial rights directed at ensuring a fair and 23

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

2.

balanced determination of the appropriate sentence. i. 6th A. Right to Counsel. ii. Disclosure of Exculpatory E (Brady). iii. 5th A. Privilege against Self-incrimination. b. Rights that DO NOT Apply at Sentencing: Special protection rights, those rights that are designed to give the D extra protections. i. Burden of proof BARD: Constitutional for state to prove facts by a preponderance of the E at sentencing. McMillan v. Pennsylvania (1986). ii. Confrontation Clause rights. iii. Double Jeopardy: DJ Clause does NOT prevent D from receiving a sentence that she has been acquitted of by initially receiving a lesser punishment. iv. Right to Jury. Sentencing Regimes a. Determinate vs. Indeterminate i. Indeterminate: Judge defines minimum and maximum sentence and actual sentence decided by parole board. ii. Determinate: Judge sets length of Ds incarceration at sentencing. iii. Large shift in 1970s toward determinate sentences. iv. Pre-Guidelines: Lots of disparity in sentencing. v. Sentencing Reform Act: Attempt to fix disparities in sentencing and factor in specific circumstances, crime seriousness, recidivism, etc. b. Guidelines: Attempt to eliminate all disparities by tying sentence to facts. i. Impossible to address all circumstances, so can have departures. ii. Some factors court CANNOT consider (e.g., wont be able to provide for family if imprisoned b/c single breadwinner in family). c. Apprendi v. New Jersey (2000): Fact that increases maximum sentence must be proven BARD to jury (EXCEPT fact of prior conviction). i. Winship (1970): Fact constituting guilt must be proved to jury BARD. ii. Almendarez-Torres (1998): Fact of prior conviction does NOT have to be proven BARD to a jury. d. Blakely v. Washington (2004): Lower range was the mandated statutory range, and to qualify for the exceptional sentence departure, the aggravating factors would need to be proven to jury BARD. e. DISSENT (Breyer): Impact of Apprendi/Blakely will: Force legislature to pass cure-determinative sentencing scheme (no min or max, but a single, rigid sentence), OR Eliminate Guidelines and push up statutory max and return to indeterminate sentencing range (too much disparity and discretion), OR Force P to charge all relevant facts necessary to be proven to jury in indictment (forcing jury to find aggravating factors at trial; harmful to Ds, even though intent of Apprendi rule was D-friendly). Only solution would be to have separate guilt/penalty trials. f. Other Apprendi Issues: How would D argue to a jury that she didnt sell drugs, but if she did the drugs were less than X amount? i. Jury must have some ultimate say in facts (goes to JN power). 24

Criminal Procedure II Fall 2011 Professor Yin Lewis & Clark Law

ii. iii. g.

h.

What import is JN in system where most cases are resolved at plea stage? P fix: In plea agreement, force D to either waive Apprendi/Blakely rights, or to admit certain facts underlying sentencing factors. iv. Takes power away from judges and pushes toward P in plea context. United States v. Booker (2005): Breyer Plurality makes Guidelines strongly advisory and changes Sentencing Reform Act. i. Calculation required, but only advisory, AND ii. Standard of review on appeal: If sentence within range it's presumptively valid; if outside range it's owed considerable discretion (i.e. cannot overturn unless unreasonable). Gall v. United States (2007): If sentence outside USSG range, it's owed considerable discretion = Appellate court cannot overturn unless unreasonable. i. Judge must calculate USSG range correctly (if incorrect, can reverse). ii. Judge can depart at her discretion: Reviewed with considerable discretion. iii. Theoretically tenuous: Guidelines not as strongly advisory cannot coexist with Apprendi; practical solution treats USSG as mandatory.

25

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Emanuel Outline - Criminal ProcedureDocument77 pagesEmanuel Outline - Criminal Procedureno contractPas encore d'évaluation

- Degroat Crim Adjudication OutlineDocument22 pagesDegroat Crim Adjudication OutlineSavana DegroatPas encore d'évaluation

- Anti-SLAPP Law Modernized: The Uniform Public Expression Protection ActD'EverandAnti-SLAPP Law Modernized: The Uniform Public Expression Protection ActPas encore d'évaluation

- Fourth Amendment: 1. Katz and Early CasesDocument29 pagesFourth Amendment: 1. Katz and Early CasesGabbie ByrnePas encore d'évaluation

- Outline Shell Midterm TortsDocument11 pagesOutline Shell Midterm Tortsexner2014Pas encore d'évaluation

- Outline-Civ.-pro II (Very Thorough)Document37 pagesOutline-Civ.-pro II (Very Thorough)adamPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil-Procedure Outline Greiner BlueberryDocument55 pagesCivil-Procedure Outline Greiner BlueberryIsaac GelbfishPas encore d'évaluation

- Cybcr OutlineDocument28 pagesCybcr Outlinedesey9Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bar Review TortDocument2 pagesBar Review Tortchristell CaseyPas encore d'évaluation

- Parties. ALIENAGE If One Party Is Citizen of Foreign State, Alienage Jdx. Satisfied, Except WhenDocument2 pagesParties. ALIENAGE If One Party Is Citizen of Foreign State, Alienage Jdx. Satisfied, Except WhenCory BakerPas encore d'évaluation

- Federal Civil Procedure OutlineDocument10 pagesFederal Civil Procedure OutlinefredtvPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence OutlineDocument17 pagesEvidence OutlineJosh PortmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Condensed Equity OutlineDocument5 pagesCondensed Equity Outlinecaribelita100% (1)

- CivPro Outline MartinDocument80 pagesCivPro Outline MartinVince DePalmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Crim OutlineDocument62 pagesCrim Outlinegialight100% (1)

- Property Outline Final-3Document35 pagesProperty Outline Final-3Santosh Reddy Somi ReddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Davis EvidenceDocument101 pagesDavis EvidenceKaren DulaPas encore d'évaluation

- Crim OutlineDocument21 pagesCrim OutlineslavichorsePas encore d'évaluation

- Real Crim Law OutlineDocument68 pagesReal Crim Law OutlineCALICLPas encore d'évaluation

- Civ Pro Outline Spring 2010Document42 pagesCiv Pro Outline Spring 2010magdalengPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Procedure - HLS - DS - Visiting ProfDocument22 pagesCivil Procedure - HLS - DS - Visiting ProfSarah EunJu LeePas encore d'évaluation

- Charging Documents Aryeh CohenDocument5 pagesCharging Documents Aryeh CohenTC JewfolkPas encore d'évaluation

- Criminal Procedure OutlineDocument45 pagesCriminal Procedure OutlineAntonio CaulaPas encore d'évaluation

- Criminal Law Outline FinalDocument39 pagesCriminal Law Outline FinalsedditPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence CapraDocument87 pagesEvidence CapraGuillermo FrênePas encore d'évaluation

- Due Process: A) Mathews Test: What Procedure Is Required?Document7 pagesDue Process: A) Mathews Test: What Procedure Is Required?Leah GaydosPas encore d'évaluation

- Civ Pro Vocab ListDocument6 pagesCiv Pro Vocab ListMolly Eno100% (1)

- Family Law - Stein Fall 2011 Outline FINALDocument93 pagesFamily Law - Stein Fall 2011 Outline FINALbiglank99Pas encore d'évaluation

- Criminal Law OutlineDocument25 pagesCriminal Law OutlinechristiandemePas encore d'évaluation

- LSE Key Concepts: Criminal Law W I C B ? M R - I: Martin v. State VariationsDocument7 pagesLSE Key Concepts: Criminal Law W I C B ? M R - I: Martin v. State VariationsLeisa R RockeleinPas encore d'évaluation

- Crim Pro BriefsDocument110 pagesCrim Pro BriefstdowgPas encore d'évaluation

- Criminal Procedure Checklist: Long DetentionDocument6 pagesCriminal Procedure Checklist: Long DetentionBree SavagePas encore d'évaluation

- Crim Pro OutlineDocument97 pagesCrim Pro Outlinejessyka109Pas encore d'évaluation

- Commencing Rep, Any Changes Should Be CommunicatedDocument8 pagesCommencing Rep, Any Changes Should Be CommunicatedHarry Kastenbaum100% (1)

- Bar Secrets: I. 3 Elements of All TortsDocument19 pagesBar Secrets: I. 3 Elements of All Tortssdcohen23Pas encore d'évaluation

- In Personam: First Question To Ask: Does The Statute (LONG ARM) Grant Jurisdiction?Document12 pagesIn Personam: First Question To Ask: Does The Statute (LONG ARM) Grant Jurisdiction?Aaron WashingtonPas encore d'évaluation

- Civ Pro II - Outline (Bahadur)Document8 pagesCiv Pro II - Outline (Bahadur)KayceePas encore d'évaluation

- Initial Contact With The Criminal Justice SystemDocument11 pagesInitial Contact With The Criminal Justice SystemAnne Ausente BerjaPas encore d'évaluation

- Admissible:Inadmissible Character EvidenceDocument7 pagesAdmissible:Inadmissible Character Evidencemdean10Pas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence Attack OutlineDocument2 pagesEvidence Attack OutlinePaulStaplesPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Procedure Cheat Sheet: by ViaDocument3 pagesCivil Procedure Cheat Sheet: by ViaMartin LaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence Outline Goodno (Spring 2013) : Exam: We Do NOT Need To Know Rule Numbers or Case Names I.PDocument36 pagesEvidence Outline Goodno (Spring 2013) : Exam: We Do NOT Need To Know Rule Numbers or Case Names I.PzeebrooklynPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Contracts OutlineDocument29 pagesFinal Contracts Outlineblondimofo100% (1)

- Crim OutlineDocument4 pagesCrim OutlineAaron FlemingPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Procedure SkeletonDocument8 pagesCivil Procedure SkeletonTOny AwadallaPas encore d'évaluation

- Professional Responsibility - MODEL RULES CHARTDocument14 pagesProfessional Responsibility - MODEL RULES CHARTGabbyPas encore d'évaluation

- Crim Pro Outline - Prof. Bandes UMiami or U of ChicagoDocument91 pagesCrim Pro Outline - Prof. Bandes UMiami or U of ChicagoEM2486Pas encore d'évaluation

- Freer NotesDocument2 pagesFreer NotesRishabh Agny100% (1)

- AnimalLaw Wagman spr04Document25 pagesAnimalLaw Wagman spr04Katie SperawPas encore d'évaluation

- Scope/Purpose/Appeals/Preliminary Questions FRE 101: Scope:: ErrorDocument15 pagesScope/Purpose/Appeals/Preliminary Questions FRE 101: Scope:: ErrorJon WhitePas encore d'évaluation

- Civ Pro OutlineDocument8 pagesCiv Pro Outlinedurangokid22Pas encore d'évaluation

- Crim Pro Outline Kroeber Summer 2009 FINALDocument13 pagesCrim Pro Outline Kroeber Summer 2009 FINALNeel VakhariaPas encore d'évaluation

- Domestic Relations - OutlineDocument15 pagesDomestic Relations - Outlinejsara1180Pas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction: 33 Questions: Federal Judicial Authority (5 Questions)Document39 pagesIntroduction: 33 Questions: Federal Judicial Authority (5 Questions)tPas encore d'évaluation

- Revisiting Asbestos Plaintiff and Fact Witness DepositionsDocument4 pagesRevisiting Asbestos Plaintiff and Fact Witness DepositionsJim DedmanPas encore d'évaluation

- MPRE Unpacked: Professional Responsibility Explained & Applied for Multistate Professional Responsibility ExamD'EverandMPRE Unpacked: Professional Responsibility Explained & Applied for Multistate Professional Responsibility ExamPas encore d'évaluation

- Divorce in Idaho: The Legal Process, Your Rights, and What to ExpectD'EverandDivorce in Idaho: The Legal Process, Your Rights, and What to ExpectPas encore d'évaluation

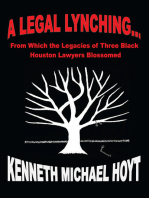

- A Legal Lynching...: From Which the Legacies of Three Black Houston Lawyers BlossomedD'EverandA Legal Lynching...: From Which the Legacies of Three Black Houston Lawyers BlossomedPas encore d'évaluation

- Outline 2018: Cultivating Professionals With Knowledge and Humanity, Thereby Contributing To People S Well-BeingDocument34 pagesOutline 2018: Cultivating Professionals With Knowledge and Humanity, Thereby Contributing To People S Well-BeingDd KPas encore d'évaluation

- Pangan v. RamosDocument2 pagesPangan v. RamossuizyyyPas encore d'évaluation

- Big Enabler Solutions ProfileDocument6 pagesBig Enabler Solutions ProfileTecbind UniversityPas encore d'évaluation

- 35 Affirmations That Will Change Your LifeDocument6 pages35 Affirmations That Will Change Your LifeAmina Km100% (1)

- Schonsee Square Brochure - July 11, 2017Document4 pagesSchonsee Square Brochure - July 11, 2017Scott MydanPas encore d'évaluation

- As Built - X-Section - 160+700 To 1660+825Document5 pagesAs Built - X-Section - 160+700 To 1660+825Md Mukul MiahPas encore d'évaluation

- Java Heritage Hotel ReportDocument11 pagesJava Heritage Hotel ReportنصرالحكمالغزلىPas encore d'évaluation

- Statistik API Development - 080117 AHiADocument6 pagesStatistik API Development - 080117 AHiAApdev OptionPas encore d'évaluation

- Ky Yeu Hoi ThaoHVTC Quyen 1Document1 348 pagesKy Yeu Hoi ThaoHVTC Quyen 1mmmanhtran2012Pas encore d'évaluation

- سلفات بحري كومنز PDFDocument8 pagesسلفات بحري كومنز PDFSami KahtaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Price Controls and Quotas: Meddling With MarketsDocument53 pagesPrice Controls and Quotas: Meddling With MarketsMarie-Anne RabetafikaPas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. Patulot - Case DigestDocument5 pagesPeople vs. Patulot - Case DigestGendale Am-isPas encore d'évaluation

- Mazda Hutapea ComplaintDocument13 pagesMazda Hutapea ComplaintKING 5 NewsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ltma Lu DissertationDocument5 pagesLtma Lu DissertationPayToWriteMyPaperUK100% (1)

- Quiz 5Document5 pagesQuiz 5asaad5299Pas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 113899. October 13, 1999. Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp., Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and Medarda V. Leuterio, RespondentsDocument12 pagesG.R. No. 113899. October 13, 1999. Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp., Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and Medarda V. Leuterio, RespondentsdanexrainierPas encore d'évaluation

- JRR Tolkein On The Problem of EvilDocument14 pagesJRR Tolkein On The Problem of EvilmarkworthingPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature - Short Stories Test 2Document22 pagesLiterature - Short Stories Test 2cosme.fulanitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Public Perceptionon Print MediaDocument8 pagesPublic Perceptionon Print MediaSeyram MayvisPas encore d'évaluation

- Progress Test 2Document5 pagesProgress Test 2Marcin PiechotaPas encore d'évaluation

- Name: Joselle A. Gaco Btled-He3A: THE 303-School Foodservice ManagementDocument3 pagesName: Joselle A. Gaco Btled-He3A: THE 303-School Foodservice ManagementJoselle GacoPas encore d'évaluation

- OneSumX IFRS9 ECL Impairments Produc SheetDocument2 pagesOneSumX IFRS9 ECL Impairments Produc SheetRaju KaliperumalPas encore d'évaluation

- Gladys Ruiz, ResumeDocument2 pagesGladys Ruiz, Resumeapi-284904141Pas encore d'évaluation

- Problem 1246 Dan 1247Document2 pagesProblem 1246 Dan 1247Gilang Anwar HakimPas encore d'évaluation

- Outpatient ClaimDocument1 pageOutpatient Claimtajuddin8Pas encore d'évaluation