Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Perspectives Issue 1

Transféré par

Tuah SujanaDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Perspectives Issue 1

Transféré par

Tuah SujanaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Perspectives Teaching Islamic Studies in higher education

Issue 1 November 2010

Perspectives

Perspectives is the magazine of the Higher Education Academys Islamic Studies Network. The Islamic Studies Network brings together those working in Islamic Studies from a wide range of disciplines to enhance teaching and learning in higher education by: hosting events and workshops; providing grants to develop teaching and learning; and encouraging the sharing of resources and good practice. For information on all our activities, visit www.heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies. Perspectives is a forum for those involved in teaching Islamic Studies in higher education to share practice and resources. As well as updates on Islamic Studies Network activity, Perspectives publishes articles on a wide range of topics related to Islamic Studies in higher education. If you would like to submit an article, highlight a set of teaching resources you have used or developed, or write a review of a book, film or other media, please contact the Academic Co-ordinator for the network, Lisa Bernasek, at l.bernasek@soton.ac.uk. Perspectives is distributed free of charge to members of the Islamic Studies Network and is available online at www.heacademy.ac.uk/ islamicstudies. To join the network, please visit our website or email islamicstudies@heacademy.ac.uk.

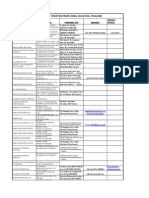

Perspectives Teaching Islamic Studies in higher education

2 3 News Welcome News from the Islamic Studies Network News from the subject centres Teaching and researching Islam in the UK: some contemporary challenges JISC digital resources for Islamic Studies Islamic Studies: discipline or specialist field? Implications for curriculum development Perspectives on Islamic Studies in higher education She who disputes: the challenges of translating the views and lived realities of those who have been otherised into policies and the curriculum Islamic law curriculum project takes the sharia challenge Designing modules for researchbased teaching in Islamic Studies Four Lions Events calendar Ron Geaves Lisa Bernasek

4 6

News Feature

11

Resources

Alastair Dunning

12

Feature

Carool Kersten

18

Report

Lisa Bernasek and Gary Bunt

24

Feature

Haleh Afshar

30

Resources

Shaheen Mansoor

32

Feature

Ayla Gl

38 40

Review

Maxim Farrar

Perspectives

Welcome

Lisa Bernasek Academic Co-ordinator, Islamic Studies Network Welcome to the first issue of Perspectives: Teaching Islamic Studies in higher education. Perspectives is the magazine of the Higher Education Academys Islamic Studies Network, and is a forum for those involved in teaching Islamic Studies to share practice and resources. Along with updates on Islamic Studies Network activity, Perspectives publishes articles related to Islamic Studies in higher education on a wide range of topics. For the first issue we have a number of pieces that will hopefully pique your interest and perhaps cause some debate. Professor Ron Geaves provides a thought-provoking article based on his many years of experience teaching and researching Islam in the UK, with a particular focus on the contemporary context and political climate. Professor the Baroness Haleh Afshar calls for interdisciplinarity as a way to bring more attention to womens voices and experiences within mainstream Islamic Studies. Both authors raise some of the ethical issues and other considerations involved when individual research interests and government policy agendas coincide. In articles focused more closely on teaching practice, Dr Carool Kersten and Dr Ayla Gl share their experiences. Dr Kersten reflects on the state of Islamic Studies as an academic field, and explores the conceptualisation of curriculum development and its implications for Islamic Studies. Dr Gl provides a rich account of the process of designing

two modules for Islamic Studies within an International Politics department, and argues for the importance of a research-based and studentcentred approach to teaching. We also have a report on some of the discussions that took place at the Islamic Studies Networks inaugural event in May 2010, and we highlight resources for Islamic Studies teaching and research that are available from JISC and from the UK Centre for Legal Education. We hope you enjoy the first edition of Perspectives. If you would like to contribute to a future issue by writing an article or case study, reviewing a book, film, or other media, or by reporting on a set of teaching resources you have used or developed, please get in touch. l.bernasek@soton.ac.uk

heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies

News from the Islamic Studies Network

Recent activity The inaugural event for the Islamic Studies Network was held on 2526 May 2010 in Birmingham. The event attracted 62 participants with a wide range of disciplinary interests, who generated interesting discussions over the two days. Papers from two of the three keynote speakers can be found on pages 6 and 24. The full event report can be downloaded from the Resources tab of our website: www. heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies. There are now over 200 people subscribed to the networks JISCmail list (ISNetwork@jiscmail.ac.uk). The list is used to send out updates on network and sector-wide activity, and is a discussion base for issues relating to Islamic Studies in higher education. Activity updates and information on funding opportunities, recent publications and resources are also provided in our quarterly online newsletter. If you would like to be added to the JISCmail list or receive the newsletter, please email: islamicstudies@heacademy.ac.uk.

Forthcoming activity The network is organising four regional workshops in 201011, the first of which was held at the University of Edinburgh on 22 October. The workshops are an opportunity for Islamic Studies practitioners to network, gain a sense of the different ways Islamic Studies is taught in a regional context, and discuss region-specific issues. The events are open to both specialists and non-specialists who teach on modules related to Islam. Future workshops dates and venues are: 10 December 2010, University of Oxford; 9 March 2011, University of Wales Trinity Saint David (Lampeter); and 26 May 2011, University of Leeds. We are also organising a two-day workshop for PhD students in Islamic Studies on 1617 February 2011 in Birmingham. This event will be an opportunity for postgraduates to network, discuss their research and teaching activities, and address issues related to life as a postgraduate and beyond. If you are interested in attending any of the workshops, please email us at: islamicstudies@ heacademy.ac.uk. The network has issued two calls for project funding this year, with two projects being funded in the first round: Dr Mark Van Hoorebeek (Lecturer in Law, University of Bradford) is developing teaching materials in the area of sharia-compliant financial instruments and intellectual property; and Dr Alison Scott-Baumann (Reader Emeritus, University of Gloucestershire) and Dr Sariya Contractor (Muslim Chaplain, University of Gloucestershire) are investigating how to encourage Muslim women into higher education through partnerships and collaborative pathways. Further information about these projects can be found on the Projects tab of our website (www.heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies). The successful projects from the second funding call will be announced in January 2011.

Perspectives

News from the subject centres

Along with contributing to cross-disciplinary network activity, colleagues from the Higher Education Academy subject centres are developing subject-specific activities for the academic year 201011. Below are some of the highlights for further information, please consult the Islamic Studies Network website (www. heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies) or the website of the relevant subject centre. In addition to the five subject centres below, the History Subject Centre (www.historysubjectcentre. ac.uk) is supporting the network and will contribute to specific activities as appropriate. Business, Management, Accountancy and Finance Network (BMAF) BMAF will hold the first meeting of its Special Interest Group for Islamic Studies on 23 March 2011 at the University of Northampton. Colleagues with an interest in any aspect of Islamic banking, finance, management and related areas are welcome to attend. This workshop will follow on from discussions held at the Islamic Studies Network inaugural event in May 2010 and will be an opportunity for participants to discuss approaches and share materials. Please register via the BMAF website. www.heacademy.ac.uk/business Subject Centre for Languages, Linguistics and Area Studies (LLAS) LLAS led on a data collection project carried out from May to August 2009 that identified over 1,000 modules in Islamic Studies and related disciplines taught at UK higher education institutions. The data gathered was analysed for a report published by HEFCE in February 2010. As follow-up to this project, LLAS is coordinating making the data collected available to the public. This database, which will be of use to students, prospective students and lecturers, will be made accessible to the public in the coming months. www.llas.ac.uk

Subject Centre for Philosophical and Religious Studies (PRS) PRS will be organising discipline-specific sessions at the Islamic Studies Networks postgraduate student event in February 2011. Colleagues at PRS are also developing two publications on Islam in Religious Studies a student guide and an edited volume on teaching Islam in Religious Studies. These publications will be valuable resources for students and lecturers working on issues related to Islam in a Religious Studies context. www.prs.heacademy.ac.uk Subject Network for Sociology, Anthropology, Politics (C-SAP) C-SAP carried out a call for case studies on teaching relating to Islam within the social sciences in the Spring and Summer of 2010. A set of ten case studies and a report that draws out the implications for teaching, learning and curriculum development on Islam within the social sciences are available at: http://stores.lulu. com/csappublications. A second call for case studies looking at the ways in which issues relating to Islam might appear in Sociology, Anthropology, Criminology or Politics courses at undergraduate or postgraduate level is now open. The case studies will be showcased at a C-SAP symposium to be held in June/July 2011. If you are interested in submitting a case study, please contact Dr Malcolm Todd at: m.j.todd@shu.ac.uk. www.c-sap.bham.ac.uk UK Centre for Legal Education (UKCLE) UKCLE has produced a set of resources related to teaching Islamic law (see Islamic law curriculum project takes the sharia challenge on page 30), which can be found on their website at: www.ukcle. ac.uk/resources/teaching-and-learning-strategies/ islamiclaw. These resources will be further developed and disseminated in 201011 through workshops for new lecturers and non-lawyers. UKCLE is also developing a Special Interest Group for Islamic law, building on the AHRC/ESRC-funded Network of British Researchers and Practitioners of Islamic Law. The first meeting of this Special Interest Group was held on 10 November 2010. www.ukcle.ac.uk

heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies

Perspectives

Teaching and researching Islam in the UK: some contemporary challenges1

Professor Ron Geaves Director of the Centre for the Applied Study of Muslims and Islam in Britain and Professor of the Comparative Study of Religion, Liverpool Hope University1 As a scholar of religion I am essentially interested in religious questions and I came to the Muslim presence in Britain through the questions: What happens to a religion when it moves from one location to another through migration? and How far can a religion be transformed by major social upheaval before it loses something so integral to itself that it ceases to be itself?2 Phrased another way, what is core to a religion and what is peripheral, what can be changed and what cannot? It was this question that brought me to the University of Leeds in 1988 to do an MA in Religious Studies under the auspices of the newly established Community Religions Project. The project, under the direction of Kim Knott, was beginning to explore the presence of religions that had arrived in Britain through migration and, as we know, radically transformed the landscape of British religious life. The Community Religions Project was groundbreaking because it was an attempt to engage Religious Studies in the academic study of migration. The literature on British Muslims was small and outside of Anthropology and Sociology very few scholars in the study of religion were researching lived religions. There was Francis Robinsons small pamphlet on the diversity of South Asian Islam, which introduced Deobandis, Barelwis, Tablighi Jamaat, Jamaati Islami, and Ahl i Hadith (Robinson 1988); Barbara Metcalfs work on South Asian Islam and its religious diversity (Metcalf

The ideas expressed in this article were first presented in The Role of Higher Education in the Integration of British Muslims, my inaugural lecture at Liverpool Hope University delivered on 12 March 2008. I had originally been inspired to ask these questions after reading the novel by David Lodge How Far Can You Go (1978), which explored the transformations in British Catholicism after World War II and particularly after Vatican II.

1982); and Roger and Catherine Ballards study of Sikhs in Leeds, which posited the well-known, four-stage development of South Asian migration into Britain (Ballard and Ballard 1977). Alison Shaw had produced work on Pakistanis in Oxford (Shaw 1988). Philip Lewis had raised the issue of what people actually did in the world of popular religion as opposed to the textual focus on historic orthodoxies in his small booklet on Pakistani shrine traditions, and paved the way for the study of Muslims as opposed to Islamic Studies (Lewis 1985). The Muslims in Britain Research Network created by Jorgen Nielson existed in its infancy. However, two events changed everything for my career. The first was the publication of Salman Rushdies The Satanic Verses. It not only transformed the Muslim communities in Britain, but it also placed an obscure area of academic study into the centre of political controversies and introduced a number of complexities in the study of Islam and Muslims in Britain. The second was more personal but still significant for the discipline. I had done my first fieldwork in 1989; working on the Ballards thesis I decided to explore the early Muslim arrivals in Leeds, testing the first stage of the development of South Asian migrant communities, that is, the early pioneers. I wanted to establish how these pioneering figures impacted upon the way that the Muslim community in Leeds organised itself religiously. It was to become my first published paper and led to a passion for fieldwork. I still grapple with the challenge of what fieldwork means for the scholar of religion as opposed to the anthropologist or the sociologist; however, in this instance I discovered painfully that working with living people is full of ethical pitfalls for the unwary. I had unwittingly got myself caught in historic divisions in the Leeds Muslim community between settlers of Pakistani and Bengali origin. My Pakistani informants had neglected to mention that a significant figure in the development of the early Leeds Muslim presence had originated from Bengal. Consequently his pioneering efforts and remarkable story did not appear in the published paper. He was upset and complained to the department. As a solution we organised an event at the City Hall in which the Mayor honoured his achievements and I spoke of his contribution to the development of Muslim religious institutions in the city. It was an important lesson that taught me that research ethics are more than fulfilling legal obligations but must be

heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies

rooted in the sensitivities of living people. We are all too familiar with the political crises that followed in the next two decades: the Gulf Wars, 9/11, 7/7, Glasgow, the War on Terror, the emphasis on radicalisation, the Governments Prevent programme, and the identification of Islamic Studies as a strategically important subject. Looking at the current situation, it would seem to me that I now gaze on a subject area that has become increasingly complex to study. In the rest of this paper I discuss two concerns that both arise out of the securitisation of the subject. They are significant for the study of religion at a wider level, and not disconnected. The first is an issue of methodology and approaches to the study of religion and concerns what has been labelled the engaged approach to the study of religion; the second is an issue of value and raises a Nietzschean dilemma. Since the events of 7/7 and subsequent religious acts of violence in Glasgow and London, the previous British Government turned its attention to the role of higher education in either preventing extremism or promoting integration. Academics have been asked to monitor students for signs of extremism and the Siddiqui Report assessed the role of departments that teach Islamic Studies in promoting integration and challenging

extremism (Siddiqui 2007). Attention turned to the education of British imams, the role of theology to counter the jihadist version of Islam and the public role of Muslim women. Those of us who study Muslims in Britain were drawn into the maelstrom of this political gaze upon our area of study. As intensely as we want to find out about the reality of Muslim experience in Britain as scholars, so too do intelligence services, police officers and Government departments. A panel organised at the 2007 European Association for the Study of Religions conference in Bremen clearly demonstrated this transformation as scholars of Islam in Europe from several European nations told how they were now in demand from intelligence agencies, Government bodies, policy makers and the media. The involvement of academics in political concerns has always been open to controversy and I am not positing answers here but posing some of the issues that I see unfolding for us as scholars when we are asked to engage with both communities and policy makers. The dangers here are several. They include the use of academic experts in a new form of McCarthyism; the use of polemical or even distorted information for policymaking bodies and courts; and, perhaps more worryingly, the labelling process involved with

Perspectives

highly charged emotive terms such as terrorist, radical, fundamentalist, or jihad. The previous Governments Prevent programme raised issues in that it generated considerable suspicion among British Muslims who regarded it as an intelligencegathering operation. It also created disquiet around who represented the Muslim communities in Britain when certain players were in receipt of large sums of Government money. For the scholar asked to act an adviser it raised a number of concerns around academic independence and the maintenance of confidence in the communities that we research. In parallel with these issues, I began to search for an alternative to the world religion tokenism that so often marks the terrain of the teaching of other religions in departments of Theology and Religious Studies, but an alternative that is also freed from the orientalist history of Islamic Studies so often critiqued by British Muslims. That prompted me to say in 2007 that the Religious Studies scholar should be considering whether the issues that we deal with and study do not allow us to sit on the fence of neutral objectivity, and that we need to squarely address the issue of advocacy (Geaves 2007). Religion has not disappeared as some secularisation theorists would have had us believe at one time but is now highly visible in the realm of crisis management, conflict resolution and violence. For me then, it is the idea of engaged religious studies that beckons but I am only too aware of the pitfalls that were highlighted by the highly publicised events that were to overtake the climate scientists of the University of East Anglia. It was around this time that I discovered the work of the anthropologist Rowena Robinson and began to consider her statement that: We may surmise that everyday life can become the terrain for the acting out of an activist politics by individuals who believe in something beyond the mundane and in the possibility of transformation and who opt to initiate the work of change in their own environments, neighbourhoods or communities. Robinson 2005, 202 Robinsons emphasis on those who believe in something beyond the mundane and in the possibility of transformation is highly relevant to the

study of religion. It is here that the phenomenological approach that has so influenced the academic study of religion can lead the way for those struggling to engage with new realities in the study of Islam. James Cox (2006), rightly identifying phenomenology as a method of studying religion that utilises empathy (seeing the world from the believers viewpoint) and epoch (no judgement is expressed through a process of bracketing out the truth claims of a religion), refers to the fact that scholars of religion are increasingly being asked to advise government and state officials or to engage in applied research activities that may involve partnerships with religious professionals and organisations. Cox argues that scholars of religion who acknowledge the significance of something beyond the mundane may find themselves natural partners with activists and links this idea of engaged religious studies to the empathetic position of the early phenomenologists. Cox is uneasy with the idea of being drawn into such alliances as it may compromise the critical scholarship involved in pure research. I would disagree. First, the issues involved in religious violence, for example, are too important for scholars of religion to remain remote. Anthropologists, sociologists and psychologists already have a track record of engagement with policy makers, religious organisations and governments that has not always been beyond reproach; for example, the history of academic involvement in the Vietnam War, Iraq and the War on Terror. It would seem to me that this complicity with the more questionable areas of state activity would alone warrant the involvement of those to whom empathy is a natural part of their personal world view and scholarly approach. Engagement does not necessarily involve the suspension or jeopardisation of critical thinking. In stating so categorically that it does, Cox returns us to an earlier paradigm where the etic and the emic are clearly demarcated, a position I believe to be negated by our human condition of subjectivity. The shift from phenomenology to engagement will require considerable reflexive skills, but the relationship of allies can also be that of critical friend. As scholars engaged in fieldwork we often talk about empowering communities that we study. We are indebted to them for much of our livelihood. If they were unwilling to co-operate with the academics who study them, our knowledge would be significantly poorer and so would our career

heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies

profiles. As researchers, we gain prestige and indeed our livelihood from our study of them. Many of the communities we study undertake to speak to our students, enable them to undertake fieldwork, and act as unpaid providers of information for student assignments. However, all the time we need to be aware of community sensitivities and the dangers of essentialising and objectifying. It is also appropriate that scholars and students of religion should put something back into these communities and offer some reciprocal benefit. One minimal expectation is that we should not remain in a universitys ivory towers, but disseminate our knowledge to improve peoples understanding and to inform public debate. As a scholar studying a western Muslim minority in a post-colonial context, I need to think about academic freedom, responsibility and what Gayatri Spivak describes as the impersonal economy of responsibility (Spivak 1992, 7). I agree with her that when we consider academic freedom we need to rethink freedom as the freedom to acknowledge insertion into responsibility (ibid.). Spivak argues that it is intrinsically impossible to choose not to be responsible (ibid., 24). However, we need to go further. Spivak appears to argue for a responsibility that is more or less based on a shared notion of common ethnic, national or community origins. Rowena Robinson does go this step further and suggests a frame of responsibility that transcends such commonalities and moves beyond an impersonal responsibility with its acknowledgment of distance: In the sphere of equal intimacy, the intimacy of love and friendship, responsibility may be a privilege more than an obligation; one is permitted responsibility, one does not merely assume it. Robinson 2005, 15 There are interesting and challenging implications resulting from these recent developments, as many second- and third-generation Muslims in Britain in the present post-9/11 and 7/7 climate feel a degree of suspicion towards the state and its motives. The British model of multiculturalism is under threat and many Muslims are not convinced that the dominant narrative of integration does not actually signify assimilation. I am often asked why a British university would involve itself in programmes that appear to be aiding the Muslim communities. I am

even asked to identify my own faith position: Am I a Christian? Am I a Muslim? Why do I not convert? Recently I was identified as a Muslim choosing to maintain taqyyah, the dispensation allowing believers to conceal their faith when under threat, compulsion or persecution. This labelling process is significant as it reveals much about the prevailing zeitgeist among British Muslims. If I am helping the Muslim community and my motives are beyond reproach then I must be a closet Muslim. If labels are essential I would prefer a friend of Muslims, with the acceptance that sometimes I will operate as a critical friend. Orientalism need not always be perceived with suspicion. It can be a quest for a deeper personal knowledge of the other, and it may take a path where the other disappears to reveal a kindred world. However, since that time two years ago I have further reflected on the situation that has arisen and will continue to arise as religion shifts from the periphery of public life to a more central concern. All too frequently academic research in the study of religion has focused purely on the creation of an academic text, useful only to debates within the subject, focusing on the analytical. Such research lauds the analytical but avoids the critical, where there is an opportunity for creating change (Zahir 2003, 203). Yet the challenge of moving from the analytical to the critical raises a crucial dilemma for us posited in the Nietzschean dichotomy of truth values and life values. Nietzsche raises the problem of the value of truth, and asks why do we not prefer untruth? Why insist on the truth? (Nietzsche 1998, 5, 13). Nietzsche believed that what he called the will to truth that is, the unquestioning faith that truth is the highest value, and the pursuit of truth at all costs drains the value out of life. This challenge lies before us as scholars. It is raised by Sophie Gilliat-Ray in her essay on deconstructing the myth of the first mosque in Cardiff (Gilliat-Ray 2010). Here we have a classic case of the collision between truth values and life values. Her research teams discovery that the Cardiff mosque was not the first in Britain added to academic truth but undermined the life value of such a truth to the Cardiff Muslim community. Muslim partners may attempt to categorise academics working alongside them in ways that pit their common ethnic, national or community origins against those of the academic. The relationship of otherness is thus perpetuated and suspicion remains.

10

Perspectives

Or they may seek ways to bridge the divide and include the academic partner in a shared economy of responsibility. Christians may be included as fellow monotheists; Jews as a fellow religious minority. Others may be included as part of a shared economy of pain. I am enough anthropologist to recognise that as a first-world, white, middle-class male it is not critical reflection or empathy, or even responsibility that separates me from the communities that I study, but security. As stated by Beatriz Manz: the inconsistency between the experience of a researcher in the field and life in the academy, the disconnection as far as security not just personal safety but material security is so great for so many anthropologists. Manz 1995, 269 I would go one step further and include psychological security. In joining with Muslim partners, forming collaborative links, helping to establish training programmes and to professionalise their various institutions and bodies, working as equals in a spirit of friendship I also enter into a partnership where I share such insecurity. References Ballard, R. and Ballard, C. (1977) The Sikhs: the development of South Asian settlements in Britain. In: Watson, J. (ed.) Between Two Cultures: Migrants and Minorities in Britain. Oxford: Blackwell. Cox, J. (2006) A Guide to the Phenomenology of Religion. London: Continuum. Geaves, R.A. (2007) Twenty years of fieldwork: reflections on reflexivity in the study of British Muslims. Inaugural Lecture. Chester: Chester Academic Press. Gilliat-Ray, S. (2010) The first registered mosque in the UK, Cardiff, 1860: the evolution of a myth. Contemporary Islam. 4 (2), 179193. Lewis, P. (1985) Pirs, Shrines and Pakistani Islam. Rawalpindi: Christian Study Centre. Lodge, D. (1978) How Far Can You Go. Harmondsworth: Penguin Manz, B. (1995) Reflections on an antropologia comprometida. In: Nordstrom, C. and Robben, A. (eds.) Fieldwork under Fire: Contemporary Studies of Violence and Survival. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, pp. 261274.

Metcalf, B.D. (1982) Islamic Revival in British India: Deoband, 18601900. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Nietzsche, F. (1998) (orig. 1885) Beyond Good and Evil. Faber, M. trans. Oxford: Oxford Worlds Classics. Robinson, F. (1988) Varieties of South Asian Islam. Research papers in Ethnic Relations. Warwick: University of Warwick Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations Robinson, R. (2005) Tremors of Violence. New Delhi: Sage Publications. Shaw, A. (1988) A Pakistani Community in Britain. Oxford: Blackwell. Siddiqui, A. (2007) Islam at Universities in England. Report submitted to the Minister of State for Lifelong Learning, Further and Higher Education. Available from: www.bis.gov.uk/assets/ biscore/corporate/migratedd/publications/d/ drsiddiquireport.pdf [18 August 2010]. Spivak, G. (1992) Thinking academic freedom in gendered post-coloniality: T.B Davie academic freedom lecture. Capetown: University of Capetown. Zahir, S. (2003) Changing views: theory and practice in a participatory community arts project. In: Puwar, N. and Raghuram, P. (eds.) South Asian Women in the Diaspora. Oxford: Berg. Bibliography Eck, D. (1993) Encountering God: A Spiritual Journey from Bozeman to Banaras. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. El-Awaisi, A. and Nye, M. (2006) Time for Change: The Future of the Study of Islam and Muslims in Universities and College in Multicultural Britain. Dundee: Al-Maktoum Institute. HEFCE (2007) Islamic Studies: current status and future prospects. Bristol: HEFCE. Available from: www.hefce.ac.uk/AboutUs/sis/islamic [18 August 2010]. Heller, A. (1984) Everyday Life. London: Routledge. Heller, A. (1990) Can Modernity Survive? Cambridge: Polity Press. Malik, I. (2007) Islamic Studies and South Asian Studies: stalemated disciplines. In: Islamic Studies: Current Status and Future Prospects. Bristol: HEFCE. Available from: www.hefce.ac.uk/ AboutUs/sis/islamic [18 August 2010]. Mason, H. (1982) Foreword to the English edition. In: Massignon, L. The Passion of Al-Hallaj Vol. 1. nceton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

11

heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies

JISC digital resources for Islamic Studies

Alastair Dunning Digitisation Programme Manager, Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) www.jisc.ac.uk/islamdigi Although much excellent work has been done in the UK to digitise medieval manuscripts like psalters, books of hours and bestiaries, Middle Eastern manuscript culture has received less attention. Such material is often hard to transliterate and study, yet UK organisations hold rich and valuable collections and there is increasing demand for access to them. The Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) has supported a number of projects to try and address this, with several UK institutions utilising JISC funding to digitise catalogue and manuscript materials relevant to Islamic Studies. As part of its Virtual Manuscript Room the University of Birmingham has made available online 71 manuscripts from its Mingana Collection, including Islamic Arabic, Syriac, Persian and Christian Arabic manuscripts. The website, which will also host materials related to the New Testament and medieval vernacular texts, is available at: www.vmr.bham.ac.uk.

Three other projects are ongoing, the fruits of which should be available in early Spring 2011. The Wellcome Trust is working with the Bibliotheca Alexandrina to digitise over 500 of the Wellcomes Islamic manuscripts, chiefly related to medicine. Kings College London are providing additional input, developing a digital catalogue tool that will be usable by similar projects in the future. The material dates from the 14th to the 20th century and comes from all over the Islamic world, stretching from Syria to South-east Asia. http://library.wellcome.ac.uk/arabicproject.html Many of the 10,000 or so Islamic texts held by the libraries of the universities of Cambridge and Oxford only have cursory descriptions on card catalogues. JISC funding is allowing the creation of fuller descriptions of their Islamic manuscripts and also ensuring they are easily searchable via their online systems. The project team is also developing a standard, using the Text Encoding Initiative, for the fuller description of Islamic manuscripts, and it is anticipated this will be adopted by other projects internationally. www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/bodley/library/ specialcollections/projects/ocimco Finally, the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) has built up a partnership with Yale University Library to digitise over 20,000 pages of Islamic manuscripts drawn from the collections of the two libraries. The digitised manuscripts will also be accompanied by the catalogues, language dictionaries and research apparatus that scholars will need to work on this often complex and demanding material. www.soas.ac.uk/ysimg

12

Perspectives

Islamic Studies: discipline or specialist field? Implications for curriculum development

Dr Carool Kersten Lecturer in Islamic Studies, Kings College London The present examination of curriculum development in Islamic Studies is informed by my research on the study of Islam as a field of scholarly investigation and my initial experiences as a lecturer in Islamic Studies in the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Kings College London, where I am responsible for offering undergraduate course modules for existing programmes and the conceptualisation, design and implementation of new modules and courses at postgraduate level1. Since the undergraduate modules are intended for non-specialists, i.e. students with little or no prior knowledge of Islam as a religious tradition and not majoring in Islamic Studies, the teaching is designed to provide a survey of key aspects of Islam as a religion and the Muslim world as a civilisation, so as to provide a holistic and multifaceted introduction to the Islamic tradition. Key considerations regarding the future development of postgraduate modules are to enrich existing programmes by offering additional elective ones, while the main incentive for the new taught MA is identifying an appropriate niche market. Consequently, the focus of the curriculum is very much content-driven. Geared towards imparting information with data as a product to be delivered, the onus for its development rests mainly on the pertaining faculty member. A complicating factor is that Islamic Studies, as a scholarly field, has been the subject of both outside scrutiny and introspection by practitioners. This has raised some generic concerns regarding the status of the field. In relation to curriculum development this raises the question whether Islamic Studies must be considered an academic discipline in its own right or a specialist field open to interdisciplinary treatment. This article is intended as a reflection on the crucial issue of a well-informed approach to curriculum development. After establishing what we mean by curriculum

development and briefly sketching the current state of affairs in the teaching of Islamic Studies as a subject of scholarly specialisation, I will relate these findings to some earlier contributions towards conceptualising curriculum development and the exploratory accounts of academic practice by fellow Islamicists. My expansion of the consequences for curriculum development is guided by Becher and Trowlers (2001) seminal study on academic cultures. Curriculum: understanding, conceptualisations, definitions When discussing the issues of curriculum design, development and change in a generic sense, Barnett et al. (2001, 435436) and Fraser and Bosanquet (2006, 269270) have noted that academics tend to be rather cavalier in the use of the term curriculum. Drawing on their common understanding, curriculum is actually used quite randomly to refer to three levels on which teaching and learning can be considered: 1. 2. 3. course/module/teaching unit; concrete study programmes or degree courses; the generic fashioning of transmitting knowledge in a given academic specialisation, which also accounts for underlying questions of epistemology and power structures.

Such understanding from the perspective of the academic providing the teaching is entirely contentdriven. In their phenomenographical examination of curriculum understandings Fraser and Bosanquet expand the research so as to also include the other stakeholder the student. This gives them four slightly different categories of curriculum (2006, 272): A. B. C. D. the structure and content of a unit (subject); the structure and content of a programme of study; the students experience of learning; a dynamic and interactive process of teaching and learning.

Kings College London, Department of Theology and Religious Studies, Undergraduate Degrees: www.kcl.ac.uk/schools/humanities/depts/trs/ug/.

In the context of an examination of the relationship between a content-driven approach to the teaching of Islam and the state of affairs in the field of Islamic Studies, I suggest that here curriculum is understood on a generic level (level 3), with an emphasis on safeguarding the integrity of structure and content on both the programme and unit level (categories A and B).

13

heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies

Islamic Studies: a field in flux With the current intense media scrutiny of Islam and Muslims, the concern with Islamic Studies as an academic specialisation within British universities has intensified, claiming the attention of specialists working in the field and those involved in higher education administration. Since 2005 no less than seven conferences and workshops have addressed Islamic Studies as a subject in tertiary education, including two consultations initiated by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), the main funding body of this field in England2. However, scholars of Islam have reflected for much longer on the state of affairs in their field. This occurred especially in the wake of Edward Saids 1978 bombshell publication, Orientalism, a scathing critique of the political agenda underlying classical orientalist scholarship and its propensity to essentialise Islam through its historical-philological approach. On closer inspection, however, it becomes evident that self-critical reflections by Islamicists on their field of specialisation actually pre-date this ideologically charged critique (Abdel Malek 1963, Adams 1967, Irwin 2006, Varisco 2005). As part of my own postgraduate research, I examined Islamic Studies in relation to other relevant specialisations such as the (generic) study of religions and area studies programmes, characterising these liaisons as awkward a reference to the troublesome mnage trois between Islamic Studies, area studies programmes and the generic field of religious studies (Kersten 2009, 244). My research concluded that in order

to adapt its approaches to both research and teaching in a rapidly changing environment, Islamic Studies must become more promiscuous to extend the conjugal metaphor a bit further as it can no longer stay faithful to the centuries-old marriage with its historical-philological partner. This means opening itself up to interdisciplinary approaches developed in other fields of religious studies as well as to a more global approach, transcending the area studies framework in which Islamic Studies is often confined to and labelled as Middle Eastern Studies. Positioning Islamic Studies in the context of cultures of academic disciplines The now classic study of Academic Tribes and Territories by Becher and Trowler (2001) provides some helpful guidance in translating developments in Islamic Studies in relation to curriculum development. The books concern with disciplinary epistemology and the phenomenology of knowledge resonates with my own research, and its contention that academic engagement and narratives with specific topics constitute important structural factors in the formulation of disciplinary cultures, has direct implications for curriculum development and change (Becher and Trowler 2001, 23). The expansion of scholarly knowledge into an increasing number of disciplines is reflected in three interconnected processes: subject parturition (new fields evolving from older ones and gradually gaining independence); subject dispersion (growth of disciplinary areas to cover more ground); and subject decline (Becher and Trowler 2001, 1415). In spite of these forces of specialisation, Becher and Trowler nevertheless see a meshing of specialisms leading towards a collective comprehensiveness of interlocking cultural communities (ibid., 1617). Consequently disciplines in higher education acquire a borderless character (ibid., 3). To my mind, Islamic Studies is also affected by such trends, refashioning academic fields in ways that must be taken into account when rethinking the curriculum. This shifting of borders evinces that the concept of an academic discipline is not altogether straightforward (ibid., 42). Although mutable and at times engaging in friendly relations with others, disciplines exhibit a degree of continuity through recognizable identities and particular cultural attributes (ibid., 44).

Islam in Higher Education conference (Subject Centre for Philosophical and Religious Studies and Association of Muslim Social Scientists, 2005); The State of Arabic and Islamic Studies in Western Universities conference (School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), 2006); Islam on Campus conference (University of Edinburgh, 2006); Roundtable meeting at Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies (2007); Islamic studies: current status and future prospects seminar (HEFCE, 2007); Islamic studies: the way forward in the UK seminar, (HEFCE, 2008); Perspectives on Islamic Studies in Higher Education conference (Islamic Studies Network, 2010).

14

Perspectives

Elaborating the complexity of such developments in a chapter called Overlaps, Boundaries and Specialisms, Becher and Trowler show that even if disciplinary classifications are not cast in stone, some borders are so strongly defended as to be virtually impenetrable; others are weakly guarded and open to incoming and outgoing traffic (ibid., 59). Demarcations of one disciplinary perspective from another can be governed by distinctions in style or emphasis, for example History versus Philosophy; a mutually agreed division of spoils such as between Physics and Chemistry; or the distinctive conceptual frameworks of sociologists and anthropologists respectively. Given that generally a considerable amount of poaching goes on across all disciplines (ibid., 59), such sharing of the ground can also lead to a convergence rather than a separation of interests (ibid., 60). Here we can think of scholars of modern languages as an example of academics who are hospitable to itinerant theories from psychology, sociology or structural anthropology or an anthropologist of religion such as the late Clifford Geertz, who identified a shift in culture and reconfiguration of social thought bringing humanities and social sciences closer together in their intellectual kinship (ibid., 62). Rather than merely recognising such developments, other educationists have pointed to active interventions to resolve counterproductive differences (Barry 1981) or to close the large gaps between disciplines (Wax 1969). For example, in an attempt to do away with disciplinaryand departmentally based structures rife with tribalism, centrifugal attitudes and artificial alienation and distance that can mar knowledge production and transmission in academia, Donald T. Campbell introduced the notion of a comprehensive, integrated multiscience or omniscience, arguing with Wax that the true basic unit of intellectual organization is the specialist field, where the closest contact is achieved between human understanding and the realm of epistemological reality it seeks to explore (Becher and Trowler 2001, 64). Along with Campbells (2005) introduction of a fish-scale model of omniscience, other characterisations for this specialism-oriented approach are Polanyis networks of overlapping neighbourhoods (1962), and Cranes honeycomb structure of interlocking fields (1972).

Islamic Studies or study of Islam? Discipline or specialism? The realisation of interdisciplinarity as the hallmark of what, I suggest, is best regarded as a field of specialisation rather than a distinct discipline, did not take hold in Islamic Studies until the 1960s. Until then, Islamicists were scholars of oriental languages with a solid grounding in historical philology. There was little interest or expertise in what was then variously called history of religions, comparative religion or phenomenology of religion, but which has since developed into the generic field of religious studies or the study of religions. This was due to mutual misconceptions regarding each others field: Islamicists regarded the religionists as students of small tribal or archaic religions whose theoretical models had nothing to offer to Islamicists, whereas religionists often felt intimidated by the linguistic aptitude and preoccupations of Islamicists, which left little time for theorising (Waardenburg 1995). In spite of the interventions of Adams (1967), Martin (1985) or Waardenburg (1995), a quick glance at the studies of Suleiman and Shihadeh (2007), Izzi Dien (2007) or Bernasek and Canning (2009) evinces the persistence of the orientalist approach, as Islamic Studies remains grounded in a firm knowledge of Arabic. This particular linguistic focus has also resulted in a geographical concentration on Middle Eastern and North African countries. Aside from the question of whether Islamic Studies should remain an orientalist field or be better integrated into the study of religions/religious studies, this also raises the issue of the relationship between Islamic Studies and area studies programmes. Due to this linguistic focus, Islamicists tend to be predominantly associated with Middle Eastern Studies and to a much lesser extent with South and South-east Asian Studies, notwithstanding the fact that one in five Muslims resides in Indonesia and that more than a quarter of a billion live in the Indian subcontinent. While area studies programmes as non-disciplinary specialist fields usually place a high value on interdisciplinarity, concerns have been raised that Middle East specialists are in danger of falling through the cracks; not recognised as full peers by either orientalists or scholars from established disciplines such as Political Science, Anthropology, Sociology, or History (Binder 1976).

15

heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies

Aside from all these differences of opinion among specialists working in the field, the issue of finding satisfactory ways of teaching Islam within the framework of meshing multidisciplinary approaches is exacerbated by an endemic lack of faculty. Here the US provides some telling figures3. In Teaching Islam, Wheeler (2003a) noted that there are an estimated 1,000 undergraduate departments and programmes in Religious Studies, many of which offer courses on Islam. However there are only roughly 100 scholars with joint specialisations in Islamic Studies and Religious Studies. In fact, specialist positions in Islamic Studies in 2003 did not nearly approximate the positions in Jewish Studies and in most Religious Studies departments there is only one token Islamicist (Wheeler 2003a, vvi). Implications for curriculum development in Islamic Studies Distinguishing between hard natural sciences and soft humanities and social sciences specialisms, Islamic Studies fits with Becher and Trowlers characterisation of the latter as reiterative; holistic (organic/river-like); value-laden and personal; concerned with particularities and complications; subject to dispute over criteria for knowledge verification and geared towards interpretation rather than explanation (Becher and Trowler 2001, 36). As for the knowledge it produces, Islamic Studies can be conceived as producing both pure and applied knowledge (the latter not only by social science projects but also by the publication of critical text editions or translations of primary material). While the orientalist approach to Islamic Studies rendered it a convergent discipline with its own methodological history grounded in philology, advocates of interdisciplinarity would qualify it as a divergent specialist field. Moreover, the study of Islam also shares with history a catholicity of coverage and relative absence of theoretical divisions (Becher and Trowler 2001, 190).

A discussion document Islamic Studies: current status and future prospects issued by HEFCE contains details on student numbers but not on faculty (HEFCE 2007, 1622).

Shifting to the conceptual approach to curriculum change inspired by the postmodernist theoretician Lyotards idea of performativity, Barnett et al. have suggested that a properly designed curriculum balances three interlocking domains: knowledge, action and self. As a specialism located in the field of the human sciences the study of Islam will privilege discipline-specific competence categorised under the rubric knowledge, while there will be only limited integration with the action domain (Barnett et al. 2001, 438). A much more contentious issue in the case of a specialism dealing with religious subjects is the impact of learning on the self. If we take Paul Tillichs definition of religion as dealing with matters of ultimate concern, it becomes understandable that the teaching of religion can potentially impact on perceptions of self and identity. Not surprisingly then, issues such as the insider/outsider perspective (McCutcheon 1999) or the place of faith in the classroom (Barbour 2009) are recurring themes in reflective writings on the teaching of religion. On a more concrete level, even when the idea of fields of academic specialisation is recognised as a more suitable taxonomy than disciplines, when it comes to curriculum design there is still the inherent multi-dimensionality of subject-based, method-based, and theory-based specialisms to be reckoned with. Here Mark C. Taylor, a theorist of religion with a generic interest in higher education, provides some useful pointers. His advocacy of deregulating and restructuring goes even a step further than re-coining academic disciplines into specialist fields. Based on the premise that responsible teaching and scholarship must become cross-disciplinary and cross-cultural, he declares separate departments obsolete and proposes instead a curriculum structured like a web or complex adaptive network (Taylor 2009). While appreciative of Fraser and Bosanquets (2006) stress on the interaction between instructor and student, Barnett et al.s (2001) use of the concept of performativity, and Taylors (2009) signalling of the interfaces between acquiring knowledge, attaining capabilities, and personal development, for the type of introductory survey courses on offer in Theology and Religious Studies programmes, the focus in the curriculum is almost unavoidably on the product, putting the onus for its development predominantly on faculty.

16

Perspectives

The findings of Teaching Islam also support such an orientation. While using explanations developed in the study of religion to contribute to our understanding of Islam, Wheeler identifies four different institutions that must be included in introductory courses on Islam: prophethood, canon and law, ritual, and society and culture (Wheeler 2003b, 34). His colleague Reinharts matrix of the Quran, the figure of Muhammad, and a historical narrative combating phenomenal and geographical essentialism has a similar point of departure and direction (2003, 2335)4. This approach does not go unchallenged; because of the transience of our technological age, Tazim Kassam has observed that what is old, ancient, and in the past has lost its cultural cach [sic] and hold over the imagination and teachers have to work harder at restoring a sense and love of history (Kassam 2003, 197). However, that does not mean a total disregard for the student perspective. On the contrary, curriculum change in the form of fine-tuning the modules on offer is very much driven by the structured student end of course feedback exercises in all Theology and Religious Studies modules. Tutorials and feedback on completed coursework can also help improve the generic objectives of modules regarding transferable skills and in imparting applied knowledge. Wheeler also argues for a pedagogical awareness in designing module content: To make the content of my course dependent upon my objective in teaching the course is to make the content justified not from a historical or factual but rather from a pedagogical perspective. This means that I want to know first not what I am teaching but why: not what facts I need to impart but what skills I am helping students develop as part of their liberal arts education. Wheeler 2003b, 14

Conclusion In view of both the above considerations and the teaching brief I have received from my institution (providing undergraduate modules on Islam as electives in existing degree courses offered by the Department of Theology and Religious Studies), I have developed my own adapted understanding of curriculum, using it as a reference to: a set of modules on Islam introducing students to Islam as a religious tradition, surveying aspects of its history, doctrines and wider cultural heritage from its inception until the present day. Together with the conceptualisations derived from the literature discussed above, it constitutes the foundation in which my own approach to curriculum design, development and change is grounded. References Abdel-Malek, A. (1963) Lorientalisme en crise. Diogne. 44, 109142. Adams, C.J. (1967) The history of religions and the study of Islam. In: Kitagawa, J. and Eliade, M. (eds.) The History of Religions: Essays on the Problems of Understanding. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 177193. Barbour, J.D. (2009) The place of personal faith in the classroom. Religious Studies News. March 2009, 21. Barnett, R. et al. (2001) Conceptualising curriculum change. Teaching in Higher Education. 6 (4), 435449. Barry, B. (1981) Do neighbours make good fences?: political theory and the territorial imperative. Political Theory. 9 (3), 293301. Becher, T. and Trowler, P.R. (2001) Academic Tribes and Territories: Intellectual Inquiry and the Culture of Disciplines. 2nd ed. Buckingham: SRHE/Open University Press. Bernasek, L. and Canning, J. (2009) Influences on the teaching of Arabic and Islamic Studies in UK higher education. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education. 8 (3), 259275. Binder, L. (1976) The Study of the Middle East: Research and Scholarship in the Humanities and Social Sciences. New York: John Wiley and Sons. Campbell, D.T. (2005) Ethnocentrism of disciplines and the fish-scale model of omniscience. In: Derry, S.J. et al. (eds.) Interdisciplinary Collaboration: An Emerging Cognitive Science. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbraum, pp. 321.

The course must be carried, I think, by some kind of narrative, and in the effort to de-essentialize the teaching of Islam, I have found a historical narrative to work best (Reinhart 2003, 26).

17

heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies

Crane, D. (1972) Invisible Colleges: Diffusion of Knowledge in Scientific Communities. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Fraser, S.P. and Bosanquet, A. (2006) The curriculum? Thats just a unit outline, isnt it? Studies in Higher Education. 31 (3), 269284. HEFCE (2007) Islamic Studies: current status and future prospects. Bristol: HEFCE. Available from: www. hefce.ac.uk/aboutus/sis/islamic/ [18 August 2010]. Irwin, R. (2006) Dangerous Knowledge: Orientalism and its Discontents. New York: Overlook Press. Izzi Dien, M. (2007) Islamic Studies or the study of Islam?: from Parker to Rammell. Journal of Beliefs & Values. 28 (3), 243255. Kassam, T. (2003) Teaching religion in the twentyfirst century. In: Wheeler, B.M. (ed.) Teaching Islam. New York and London: Oxford University Press, pp. 191215. Kersten, K.P.L.G. (2009) Occupants of the Third Space: New Muslim Intellectuals and the Study of Islam (Nurcholish Madjid, Hasan Hanafi, Mohammed Arkoun). Ph.D. Thesis, School of Oriental and African Studies. Martin, R.C. (ed.) (1985) Approaches to Islam in Religious Studies. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. McCutcheon, R.T. (ed.) (1999) The Insider/Outsider Problem in the Study of Religion: A Reader. London and New York: Cassell. Polanyi, M. (1962) The republic of science. Minerva. 1 (1), 5473. Reinhart, A.K. (2003) On The Introduction of Islam. In: Wheeler, B.M. (ed.) Teaching Islam. New York and London: Oxford University Press, pp. 2245. Said, E.W. (1995 [1978]) Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient. 2nd ed. London: Penguin. Suleiman, Y. and Shihadeh, A. (2007) Islam on Campus: teaching Islamic Studies at Higher Education Institutions in the UK, Report of a conference held at the University of Edinburgh, 4 December 2006. Journal of Beliefs & Values. 28 (3), 309329. Taylor, M.C. (2009) End the university as we know it. The New York Times. 27 April, p. A23. Available from: www.nytimes.com/2009/04/27/ opinion/27taylor.html [25 August 2010]. Varisco, D.M. (2005) Islam Obscured: The Rhetoric of Anthropological Representation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Waardenburg, J. (ed.) (1995) Scholarly Approaches to Religion, Interreligious Perceptions, and Islam. Bern: Peter Lang.

Wax, M.L. (1969) Myth and interrelationship in social science. In: Sherif, M. and Sherif, C. (eds.) Interdisciplinary Relationships in the Social Sciences. Chicago, IL: Aldine. Wheeler, B.M. (ed.) (2003a) Teaching Islam. New York and London: Oxford University Press. Wheeler, B.M. (2003b) What cant be left out: the essentials of teaching Islam as a religion. In: Wheeler, B.M. (ed.) Teaching Islam. New York and London: Oxford University Press, pp. 321. Bibliography Nanji, A. (ed.) (1997) Mapping Islamic Studies: Genealogy, Continuity and Change. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Saeed, A. (1999) Towards religious tolerance through reform in Islamic education: the case of the State Institute for Islamic Studies in Indonesia. Indonesia and the Malay World. 27 (79), 178191. Siddiqui, A. (2007) Islam at Universities in England. Report submitted to the Minister of State for Lifelong Learning, Further and Higher Education. Available from: www.bis.gov.uk/assets/ biscore/corporate/migratedd/publications/d/ drsiddiquireport.pdf [18 August 2010].

18

Perspectives

Perspectives on Islamic Studies in higher education

Dr Lisa Bernasek Academic Co-ordinator, Islamic Studies Network Dr Gary Bunt Subject Co-ordinator, Subject Centre for Philosophical and Religious Studies and Senior Lecturer in Islamic Studies, University of Wales Trinity Saint David With contributions from the Islamic Studies Network project team The Islamic Studies Network held its inaugural event, Perspectives on Islamic Studies in higher education, on 2526 May 2010. During the event participants attended two workshop sessions to discuss their personal perspectives on issues in teaching Islamic Studies in higher education. The first set of workshops were organised around a disciplinary theme, with participants choosing to attend groups based on their departmental or disciplinary interests. Six workshops ran in parallel, each chaired by an academic who opened the session with some reflections on teaching Islamic Studies from a particular disciplinary perspective. Participants then shared their own experiences, discussing matters ranging from textbooks to student expectations to the influence of lecturers experience on their teaching. As full reports on all the discussions would run to several thousand words, this article presents key themes discussed in each workshop. Areas of interest identified for further discussion and development within the Network can be found in boxes on the following pages. All points are anonymous, and are not placed in any specific order of preference. Full subject-specific reports may be published by individual subject centres in due course.

Parallel session 1: Theology and Religious Studies Chair: Professor Hugh Goddard (University of Edinburgh) Many Theology and Religious Studies departments have solo Islamic Studies lecturers, with the majority of their students aiming to progress into teaching in the primary and secondary sectors. Academics in these departments often lack the support of language studies and are required to teach across the discipline rather than specialising in one topic within Islamic Studies. The cohort of students has changed over the years, and it can be problematic balancing the expectations of increasingly diverse students. The differences within student constituencies (including diverse cultural and belief perspectives) mean that there are issues in the ways in which students are assessed and benchmarks set. For example, preexisting understandings of Islam may vary from very detailed and within a particular faith perspective, through to no knowledge. Questions relating to the difficulties of teaching introductions to Islam were also raised. How can the subject be taught compatibly with the standards and expectations of UK higher education and without becoming orientalist? How can stereotypes be broken while conveying the idea that Islam is different from Christian theology? Can we challenge the type of Islam that is being taught? How can Islam be introduced to students without using well-known paradigms and familiar narrative histories? Can academics provide students with an interrogative framework and encourage them to be inquisitive in their approach Islam? Can this be achieved through university lectures and seminars?

The breadth of participant interests was both surprising and interesting.

The discussions and workshops and exchanges of views were the best aspects of the event.

It was all just degrees of excellence a thoroughly stimulating event.

19

heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies

Parallel session 2: Languages, Linguistics and Area Studies Chair: Dr Barbara Zollner (Birkbeck College) There is an overall domination of Middle Eastern Studies in Area Studies programmes related to Islam. This means that other areas of the Muslim world (e.g. South Asia) or issues related to Muslims in Europe or North America are marginalised. Although Area Studies departments should provide a space for interdisciplinary work and reflection, Islamic Studies specialists in these departments often tend to identify with their individual disciplines (e.g. Religious Studies, History, Politics) rather than Area Studies more generally. This situation is exacerbated by the distinction between the social sciences and the humanities, as specialists in Islam are often separated by this structural division. In some social science contexts there is an attempt to avoid questions of religion and to frame discussions around culture. The study of Islam in language-oriented degree courses (e.g. Arabic or Arabic and Islamic Studies) presents a tendency to focus on Arabic when studying Islam, resulting in the marginalisation of other relevant languages. Because the study of languages is not facilitated in the UK educational system, students pursuing these degrees may be faced with difficulties as starting language programmes ab initio implies devoting a significant amount of time to language training. In consequence of this it can be difficult to find the balance between teaching content (including coverage of Islam) and language.

Parallel session 3: History Chair: Dr Anna Akasoy (University of Oxford) As with many disciplines related to Islamic Studies, historians may be located in a History department or within an Area Studies context. These contexts will entail different expectations in relation to modules delivered and student backgrounds. Issues in teaching Islamic history to students without a background in Islam were raised. This type of module can easily centre on teaching facts and events rather than using thematic approaches or exploring current research in the field. Participants discussed approaches to teaching Islam within History as well as the development of bibliographical resources, including the upcoming publication of a section of the Oxford Bibliographies Online (OBO) devoted to Islamic Studies1.

Reisz, M. (2010) Research intelligence: Thats your reading sorted. Times Higher Education, 27 May. Available from: www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/ story.asp?sectioncode=26&storycode=411727 &c=2 [25 August 2010]. Oxford Bibliographies Online: www.oxfordbibliographiesonline.com/

20

Perspectives

Parallel session 4: Sociology, Anthropology and Politics Chairs: Dr Sophie Gilliat-Ray (Cardiff University), Dr Sen McLoughlin (University of Leeds) Those present working in Religious Studies departments approach their research and teaching using sociological or anthropological methods, but have found these departments less likely to be interested in the sociology/anthropology of religion. According to the group, sociology of religion is not generally valued within Sociology departments; it also has little contact with the sociology of race. There was some discussion in the workshop of whether there is a sociology of Islam, and what this might look like. Within Politics, there was some discussion of the limitation of traditional teaching methods in relation to Islam. In a module on Political Islam, for example, it is often necessary to provide students with an introduction to Islam, but a cursory overview may actually reinforce their stereotypes. Participants also noted that Politics modules related to Islam are popular options within degree courses. One challenge common to all these disciplines is that students need to develop methodological skills (qualitative research, research design, etc.) and need to understand the history, diversity, and institutions related to Muslim communities in the UK and elsewhere. Students are driven by contemporary social issues, so discussion of Islam in context, related to other aspects of society, works well. However, it was also noted that lecturers often have to dispel students myths about Islam or parts of the Muslim world when teaching. There was some discussion of the need for further interdisciplinary work, and the need to adjust university structures so that this type of work can take place. There was also discussion of the term Islamic Studies what does this entail in relation to the social sciences?

Parallel session 5: Business, Management and Finance Chair: Mr Osama Khan (University of Surrey) Islamic banking, finance and economics were found to be the main focus of teaching in these disciplinary areas, although one case study of supply chain management in relation to Islamic Studies was discussed. There was a general interest in investigating further provision in this area, and in other areas like management, marketing, and human resources. In general Islamic finance, banking and management are being taught as an alternative to models discussed in the core Business curriculum. The aim is to expose students to the wide range of ideas related to these topics, not to question particular ideas or rulings. These topics may be offered as modules in their own right or through sub-modular provision. It was pointed out that often lecturers are the sole person working on Islamic finance at their universities. This raises the need for further collaboration between people at different universities. In addition, research work is taking place in Business schools but also in other departments, so there is a need for dissemination of research across disciplines, and for the development of learning and teaching materials related to this research.

21

heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies

Parallel session 6: Law Chair: Professor Shaheen Sirdar Ali (University of Warwick) Teaching Islamic Law is generally done from a comparative perspective, with the idea of the Western legal system as the benchmark against which scholars compare elements of Islamic law. Islamic legal methodology can cause dilemmas as the diversity and complexity of the different schools of legal thought (madhhabs) can be confusing for students. There is great diversity not only in the opinions of different schools but also between Sunni and Shiite approaches, and between classical and modern scholars. There are challenges in explaining how the same sources can be interpreted very differently. In addition, legal terminology is often challenging to understand. This is related to questions of translation; the translation of documents was generally agreed to be useful; however, it must be borne in mind that there can be different interpretations of the same word that may not be reflected in a translation. It was agreed that certain terms and concepts carry cultural baggage. Therefore the syllabus needs to be practical and diverse in order to help students understand the terminology. There was also an interest in understanding the application of Islamic law in contemporary society, and looking at Islamic law scholarship in the UK and beyond. There was some discussion of the development of Islamic law in mainland Europe in comparison to the UK. It was also suggested that investigating how Islamic Law courses are being taught in Muslim institutions both here and outside the UK would be useful for the cross-fertilisation of ideas.

Parallel workshops: cross-disciplinary issues In the second set of workshops, participants attended three parallel sessions to discuss cross-disciplinary issues that may arise in teaching Islamic Studies. Members of the Islamic Studies Network project team introduced the network and the Higher Education Academys previous work related to Islamic Studies. Participants were given an overview of the networks upcoming activity and how they could get involved2. Participants were then asked to discuss a selection of cross-disciplinary issues in small groups. These topics included: teaching introductory courses; resource sharing and curriculum development, including online resources; student recruitment and employability; teaching in relation to political issues and current events; collaboration (between disciplines or institutions) in teaching; diversity of Islamic Studies programmes and academic expectations; dialogue with Muslim communities and institutions.

In the discussion groups a number of general issues arose, as well as suggestions for future work the network could help to facilitate. Some of the main issues are presented below. Defining Islamic Studies The definition of Islamic Studies was discussed in the workshops and over the course of the event. In one workshop participants discussed whether the Islamic Studies Network was engaging in the creation or construction of Islamic Studies as a discipline, and if the network was in danger of becoming a selfselecting shaper of that discipline. There was some concern at the possibly exclusionary implications of this, and the potential for creating a core and periphery of knowledge and practices.

See PowerPoint presentation available at: www.heacademy.ac.uk/events/detail/2010/ academyevents/25-26_May_2010_Islamic_ Studies_Network_Event.

22

Perspectives

This point was raised in the final summing-up session of the conference as well, with participants wondering exactly who was or should be included in the definition of an Islamic Studies academic. It was emphasised that the network was meant to be as inclusive as possible, and that a special effort should be made to draw in participants who are teaching only a small amount of content related to Islam. This could be done through training events and resources specifically for those who do not see themselves as specialists in Islam, but who are involved in teaching subjects related to Islam and Muslims. Student backgrounds and expectations Issues related to student backgrounds and expectations, as well as employability issues, arose in all three parallel sessions. There was discussion of the varieties of student knowledge, and how introductory courses might relate to this knowledge as well as to different disciplinary frameworks. Although many students come into Islamic Studies with an interest in academia or teaching, there are other career paths as well, including in Islamic finance, chaplaincy, and as family law solicitors or expert witnesses. Regarding student expectations, there was some discussion of the dangers of student disappointment with academic study. Institutions expect that Islamic Studies be treated in the same way as any other subject (in relation to quality assurance, etc.), and students must take an academic approach. It was suggested that this approach might cause disappointment by bringing uncertainty to some Muslim students understanding of Islam. However, it was also suggested that this process was not limited to the Islamic faith but might be confronted by students of many faiths, and that researching and learning new approaches was part of the experience of higher education. Interaction and dialogue with Muslim communities and institutions The issue of interaction and dialogue with Muslim communities and institutions was raised in all three parallel sessions, emphasising the importance of future work in this area. Various models of interaction were discussed. For example, universities may offer evening and extension courses to local communities. This can be a positive way to create dialogue, but participants had had differing experiences

related to this. Universities also have a role to play in accreditation and validation of programmes at Muslim institutions. It was agreed that an investigation of practice and educational techniques in faith-based institutions compared with universities would be fruitful for both sides. Participants also discussed what the place of such institutions is in relation to the network. Are such institutions properly able to be part of the network? Are they potential partners or stakeholders? To what extent is it the networks role to build dialogue and encourage practice-sharing? It was acknowledged that this dialogue can be difficult for funding bodies to sponsor or carry out. Resources and methods There was discussion of resource sharing in all the workshops, with participants mentioning current projects that can be used and discussing the potential for future resource sharing through the Islamic Studies Network. HumBox, an open educational resources project developed by the humanities subject centres, is one possibility for sharing teaching resources, e.g. PowerPoint slides, lecture notes, handouts, film clips, etc. used in teaching. Users can also create profiles with teaching and research interests3. Another project that has already developed extensive teaching resources is the UKCLE Islamic law curriculum project. Teaching manuals, a bibliography and a glossary have been developed and are available online4. Concluding comment The workshops generated a great deal of discussion, some of which continued outside of the conference rooms, and demonstrated that those working in the fields associated with the study of Islam have a dynamic and passionate interest in how their subject is taught across a variety of institutions. It is anticipated that the points presented above from the sessions will inform wider debates on Islamic Studies, as well as the future activities of the network.

3 4

HumBox: www.humbox.ac.uk UKCLE, Developing an Islamic law curriculum: Resources: www.ukcle.ac.ukresources/teachingand-learning-strategies/islamiclaw.

23

heacademy.ac.uk/islamicstudies

Areas of future work