Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Theatre Arts

Transféré par

Jae Mary LeysonDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Theatre Arts

Transféré par

Jae Mary LeysonDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

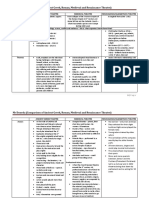

Ancient Greek Theatre Playwrights Aeschylus Aristophanes Euripides Sophocles

y y y y y

The Greek theatre history began with festivals honoring their gods. A god, Dionysus, was honored with a festival called by "City Dionysia". In Athens, during this festival, men used to perform songs to welcome Dionysus. Plays were only presented at City Dionysia festival. Athens was the main center for these theatrical traditions. Athenians spread these festivals to its numerous allies in order to promote a common identity. At the early Greek festivals, the actors, directors, and dramatists were all the same person. After some time, only three actors were allowed to perform in each play. Later few non-speaking roles were allowed to perform on-stage. Due to limited number of actors allowed on-stage, the chorus evolved into a very active part of Greek theatre. Music was often played during the chorus' delivery of its lines.

Tragedy, comedy, and satyr plays were the theatrical forms. Tragedy and comedy were viewed as completely separate genres. Satyr plays dealt with the mythological subject in comic manner. Aristotle's Poetics sets out a thesis about the perfect structure for tragedy. Tragedy plays Thespis is considered to be the first Greek "actor" and originator of tragedy (which means "goat song", perhaps referring to goats sacrificed to Dionysus before performances, or to goat-skins worn by the performers.) However, his importance is disputed, and Thespis is sometimes listed as late as sixteenth in the chronological order of Greek tragedians. Aristotle's Poetics contain the earliest known theory about the origins of Greek theatre. He says that tragedy evolved from dithyrambs, songs sung in praise of Dionysus at the Dionysia each year. The dithyrambs may have begun as frenzied improvisations but in the 600s BC, the poet Arion is credited with developing the dithyramb into a formalized narrative sung by a chorus. Three well-known Greek tragedy playwrights of the fifth century are Sophocles, Euripides and Aeschylus. Comedy plays Comedy was also an important part of ancient Greek theatre. Comedy plays were derived from imitation; there are no traces of its origin. Aristophanes wrote most of the comedy plays. Out of these 11 plays survived - Lysistrata, a humorous tale about a strong woman who leads a female coalition to end war in Greece. Greek Theatre Theatre buildings were called a theatron. The theaters were large, open-air structures constructed on the slopes of hills. They consisted of three main elements: the orchestra, the skene, and the audience. Orchestra: A large circular or rectangular area at the center part of the theatre, where the play, dance, religious rites, acting used to take place. Skene: A large rectangular building situated behind the orchestra, used as a backstage. Actors could change their costumes and masks. Earlier the skene was a tent or hut, later it became a permanent stone structure. These structures were sometimes painted to serve as backdrops. Rising from the circle of the orchestra was the audience. The theatres were originally built on a very large scale to accommodate the large number of people on stage, as well as the large number of people in the audience, up to fourteen thousand.

Acting The cast of a Greek play in the Dionysia was comprised of amateurs, not professionals (all male). Ancient Greek actors had to gesture grandly so that the entire audience could see and hear the story. However most Greek theatres were cleverly constructed to transmit even the smallest sound to any seat. Costumes and Masks The actors were so far away from the audience that without the aid of exaggerated costumes and masks. The masks were made of linen or cork, so none have survived. Tragic masks carried mournful or pained expressions, while comic masks were smiling or leering. The shape of the mask amplified the actor's voice, making his words easier for the audience to hear. The characteristics of Roman to those of the earlier Greek theatres due in large part to its influence on the Roman triumvir Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus. Much of the architectural influence on the Romans came from the Greeks, and theatre structural design was no different from other buildings. However, Roman theatres have specific differences, such as being built upon their own foundations instead of earthen works or a hillside and being completely enclosed on all sides. Roman theatres derive their basic design from the Theatre of Pompey, the first permanent Roman theatre. Theatre structure Roman theatres were built in all areas of the empire from medieval-day Spain, to the Middle East. Because of the Romans' ability to influence local architecture, we see numerous theatres around the world with uniquely Roman attributes.[1] There exist similarities between the theatres and amphitheatres of ancient Rome/Italy. They were constructed out of the same material, Roman concrete, and provided a place for the public to go and see numerous events throughout the Empire. However, they are two entirely different structures, with specific layouts that lend to the different events they held. Amphitheatres did not need superior acoustics, unlike those provided by the structure of a Roman theatre. While amphitheatres would feature races and gladiatorial events, theatres hosted events such as plays, pantomimes, choral events, and orations. Their design, with its semicircular form, enhances the natural acoustics, unlike Roman amphitheatres constructed in the round.[1] These buildings were semi-circular and possessed certain inherent architectural structures, with minor differences depending on the region in which they were constructed. The scaenae frons was a high back wall of the stage floor, supported by columns. The proscaenium was a wall that supported the front edge of the stage with ornately decorated niches off to the sides. The Hellenistic influence is seen through the use of the proscaenium. The Roman theatre also had a podium, which sometimes supported the columns of the scaenae frons. The scaenae was originally not part of the building itself, constructed only to provide sufficient background for the actors. Eventually, it became a part of the edifice itself, made out of concrete. The theatre itself was divided into the stage (orchestra) and the seating section (auditorium). Vomitoria or entrances and exits were made available to the audience.[2] The auditorium, the area in which people gathered, was sometimes constructed on a small hill or slope in which stacked seating could be easily made in the tradition of the Greek Theatres. The central part of the auditorium was hollowed out of a hill or slope, while the outer radian seats required structural support and solid retaining walls. This was of course not always the case as Romans tended to build their theatres regardless of the availability of hillsides. All theatres built within the city of Rome were completely man-made without the use of earthworks. The auditorium was not roofed; rather, awnings (vela) could be pulled overhead to provide shelter from rain or sunlight.[3] Some Roman theatres, constructed of wood, were torn down after the festival for which they were erected concluded. This practice was due to a moratorium on permanent theatre structures that lasted until 55 BC when the Theatre of Pompey was built with the addition of a temple to avoid the law. Some Roman theatres show signs of never having been completed in the first place.[4] Inside Rome, few theatres have survived the centuries following their construction, providing little evidence about the specific theatres. Arausio, the theatre in modern-day Orange, France, is a good example of a classic Roman theatre, with an indented scaenae frons, reminiscent of Western Roman theatre designs, however missing the more ornamental structure. The Arausio is still standing today and, with its amazing structural acoustics and having had its seating reconstructed, can be seen to be a marvel of Roman architecture

History of Drama Ancient Drama The origins of Western drama can be traced to the celebratory music of 6th-century BC Attica, the Greek region centered on Athens. Although accounts of this period are inadequate, it appears that the poet Thespis developed a new musical form in which he impersonated a single character and engaged a chorus of singer-dancers in dialogue. As the first composer and soloist in this new form, which came to be known as tragedy, Thespis can be considered both the first dramatist and the first actor. Of the hundreds of works produced by Greek tragic playwrights, only 32 plays by the three major innovators in this new art form survive. Aeschylus created the possibility of developing conflict between characters by introducing a second actor into the format. His seven surviving plays, three of which constitute the only extant trilogy are richly ambiguous inquiries into the paradoxical relationship between humans and the cosmos, in which people are made answerable for their acts, yet recognize that these acts are determined by the gods. Restoration And 18th-Century Drama The theaters established in the wake of Charles II's return from exile in France and the Restoration of the monarchy in England (1660) were intended primarily to serve the needs of a socially, politically, and aesthetically homogeneous class. At first they relied on the pre-Civil War repertoire; before long, however, they felt called upon to bring these plays into line with their more "refined," French-influenced sensibilities. The themes, language, and dramaturgy of Shakespeare's plays were now considered out of date, so that during the next two centuries the works of England's greatest dramatist were never produced intact. Owing much to Moliere, the English comedy of manners was typically a witty, brittle satire of current mores, especially of relations between the sexes. Among its leading examples were She Would if She Could (1668) and The Man of Mode (1676) by Sir George Etherege; The Country Wife (1675) by William Wycherley; The Way of the World (1700) by William Congreve; and The Recruiting Officer (1706) and The Beaux' Stratagem (1707) by George Farquhar. The resurgence of Puritanism, especially after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, had a profound effect on 18th-century drama. Playwrights, retreating from the free-spirited licentiousness of the Restoration, turned towards ofter, sentimental comedy and moralizing domestic tragedy. The London Merchant (1731) by George Lillo consolidated this trend.A prose tragedy of the lower middle class, and thus an important step on the road to realism, it illustrated the moral that a woman of easy virtue can lead an industrious young man to the gates of hell. Satire enjoyed a brief revival with Henry Fielding and with John Gay, whose The Beggar's Opera (1728) met with phenomenal success. Their wit, however, was too sharp for the government, which retaliated by imposing strict censorship laws in 1737. For the next 150 years, few substantial English authors bothered with the drama. 19th Century Drama and The Romantic Rebellion In its purest form, Romanticism concentrated on the spiritual, which would allow humankind to transcend the limitations of the physical world and body and find an ideal truth. Subject matter was drawn from nature and "natural man" (such as the supposedly untouched Native American). Perhaps one of the best examples of Romantic drama is Faust (Part I, 1808; Part II, 1832) by the German playwright Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Based on the classic legend of the man who sells his soul to the devil, this play of epic proportions depicts humankind's attempt to master all knowledge and power in its constant struggle with the universe. The Romantics focused on emotion rather than rationality, drew their examples from a study of the real world rather than the ideal, and glorified the idea of the artist as a mad genius unfettered by rules. Romanticism thus gave rise to a vast array of dramatic literature and production that was often undisciplined and that often substituted emotional manipulation for substantial ideas. Romanticism first appeared in Germany, a country with little native theatre other than rustic farces before the 18th century. By the 1820s Romanticism dominated the theatre of most of Europe. Many of the ideas and practices of Romanticism were evident in the late 18th-century Sturm und Drang movement of Germany led by Goethe and the dramatist Friedrich Schiller. These plays had no single style but were generally strongly emotional, and, in their experimentation with form, laid the groundwork for the rejection of Neo-Classicism. The plays of the French playwright Ren Charles Guilbert de Pixrcourt paved the way for French Romanticism, which had previously been known only in the acting of Franois Joseph Talma in the first decades of the 19th century. Victor Hugo's Hernani (1830) is considered the first French Romantic drama. The Modern Drama From the time of the Renaissance on, theatre seemed to be striving for total realism, or at least for the illusion of reality. As it reached that goal in the late 19th century, a multifaceted, antirealistic reaction erupted. Avant-garde Precursors of Modern Theatre Many movements generally lumped together as the avant-garde, attempted to suggest alternatives to the realistic drama and production. The various theoreticians felt that Naturalism presented only superficial and thus limited or surface reality-that a greater truth or reality could be found in the spiritual or the unconscious. Others felt that theatre had lost touch with its origins and had no meaning for modern society other than as a form of entertainment. Paralleling modern art movements, they turned to symbol,

abstraction, and ritual in an attempt to revitalize the theatre. Although realism continues to be dominant in contemporary theatre, television and film now better serve its earlier functions. The originator of many antirealist ideas was the German opera composer Richard Wagner. He believed that the job of the playwright/composer was to create myths. In so doing, Wagner felt, the creator of drama was portraying an ideal world in which the audience shared a communal experience, perhaps as the ancients had done. He sought to depict the "soul state", or inner being, of characters rather than their superficial, realistic aspects. Furthermore, Wagner was unhappy with the lack of unity among the individual arts that constituted the drama. He proposed the Gesamtkunstwerk, the "total art work", in which all dramatic elements are unified, preferably under the control of a single artistic creator. Wagner was also responsible for reforming theatre architecture and dramatic presentation with his Festival Theatre at Bayreuth, Germany, completed in 1876. The stage of this theatre was similar to other 19th-century stages even if better equipped, but in the auditorium Wagner removed the boxes and balconies and put in a fan-shaped seating area on a sloped floor, giving an equal view of the stage to all spectators. Just before a performance the auditorium lights dimmed to total darkness-then a radical innovation. Symbolist Drama The Symbolist movement in France in the 1880s first adopted Wagner's ideas. The Symbolists called for "detheatricalizing" the theatre, meaning stripping away all the technological and scenic encumbrances of the 19th century and replacing them with a spirituality that was to come from the text and the acting. The texts were laden with symbolic imagery not easily construed-rather they were suggestive. The general mood of the plays was slow and dream-like. The intention was to evoke an unconscious response rather than an intellectual one and to depict the nonrational aspects of characters and events. The Symbolist plays of Maurice Maeterlinck of Belgium and Paul Claudel of France, popular in the 1890s and early 20th century, are seldom performed today. Strong Symbolist elements can be found, however, in the plays of Chekhov and the late works of Ibsen and Strindberg. Symbolist influences are also evident in the works of such later playwrights as the Americans Eugene O'Neill and Tennessee Williams and the Englishman Harold Pinter, propounder of "theatre of silence". Also influenced by Wagner and the Symbolists were the Swiss scenic theorist Adolphe Appia and theEnglish designer Edward Henry Gordon Craig, whose turn-of-the-century innovations shaped much of 20th-century scenic and lighting design. They both reacted against the realistic painted settings of the day, proposing instead suggestive or abstract settings that would create, through light and scenic elements, more of a mood or feeling than an illusion of a real place. In 1896 a Symbolist theatre in Paris produced Alfred Jarry's Ubu roi, for its time a shocking, bizarre play. Modelled vaguely on Macbeth, the play depicts puppet-like characters in a world devoid of decency. The play is filled with scatological humor and language. It was perhaps most significant for its shock value and its destruction of virtually allcontemporaneous theatrical norms and taboos. Ubu roi freed the theatre for exploration in any direction the author wished to go. It also served as the model and inspiration for future avant-garde dramatic movements and the absurdist drama of the 1950s. Expressionist Drama The Expressionist movement was popular in the 1910s and 1920s, largely in Germany. It explored the more violent, grotesque aspects of the human psyche, creating a nightmare world onstage. Scenographically, distortion and exaggeration and a suggestive use of light and shadow typify Expressionism. Stock types replaced individualized characters or allegorical figures, much as in the morality plays, and plots often revolved around the salvation of humankind. Other movements of the first half of the century, such as Futurism, Dada, and Surrealism, sought to bring new artistic and scientific ideas into theatre. Ensemble Theatre Perhaps the most significant development influenced by Artaud was the ensemble theatre movement of the 1960s. Exemplified by the Polish Laboratory Theatre of Jerzy Grotowski, Peter Brook's Theatre of Cruelty Workshop, Thtre du Soleil, the French workers' cooperative formed by Ariane Mnouchkine, and the Open Theatre, led by Joseph Chaikin, ensemble theatres abandoned the written text in favor of productions created by an ensemble of actors.The productions, which generally evolved out of months of work, relied heavily on physical movement, nonspecific language and sound, and often-unusual arrangements of space . Absurdist Theatre The most popular and influential nonrealistic genre of the 20th century was absurdism. Absurdist dramatists saw, in the words of the Romanian-French playwright Eugne Ionesco, "man as lost in the world, all his actions become senseless, absurd, useless. Absurdist drama tends to eliminate much of the cause-and-effect relationship among incidents, reduce language to a game and minimize its communicative power, reduce characters to archetypes, make place nonspecific, and view the world as alienating and incomprehensible. Absurdism was at its peak in the 1950s, but continued to influence drama through the 1970s. The American playwright Edward Albee's early dramas were classified as absurd because of the seemingly illogical or irrational elements that defined his characters' world of actions. Pinter was also classed with the absurdists. His plays, such as The Homecoming (1964), seem dark, impenetrable, and absurd. Pinter explained, however, that they are realistic because they resemble the everyday world in which only fragments of unexplained activity and dialogue are seen and heard.

Contemporary Drama Although pure Naturalism was never very popular after World War I, drama in a realist style continued to dominate the commercial theatre, especially in the United States. Even there, however, psychological realism seemed to be the goal, and nonrealistic scenic and dramatic devices were employed to achieve this end. The plays of Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams, for instance, use memory scenes, dream sequences, purely symbolic characters, projections, and the like. Even O'Neill's later works-ostensibly realistic plays such as Long Day's Journey into Night (produced 1956)-incorporate poetic dialogue and a carefully orchestrated background of sounds to soften the hard-edged realism. Scenery was almost always suggestive rather than realistic. European drama was not much influenced by psychological realism but was more concerned with plays of ideas, as evidenced in the works of the Italian dramatist Luigi Pirandello, the French playwrights Jean Anouilh and Jean Giraudoux, and the Belgian playwright Michel de Ghelderode. In England in the 1950s John Osborne's Look Back in Anger (1956) became a rallying point for the postwar "angry young men"; a Vietnam trilogy of the early 1970s, by the American playwright David Rabe, expressed the anger and frustration of many towards the war in Vietnam. Under he influence of Brecht, many postwar German playwrights wrote documentary dramas that, based on historical incidents, explored the moral obligations of individuals to themselves and to society. An example is The Deputy (1963), by Rolf Hochhuth, which deals with Pope Pius XII's silence during World War II. Many playwrights of the 1960s and 1970s-Sam Shepard in the United States, Peter Handke in Austria, Tom Stoppard in Englandbuilt plays around language: language as a game, language as sound, language as a barrier, language as a reflection of society. In their plays, dialogue frequently cannot be read simply as a rational exchange of information. Many playwrights also mirrored society's frustration with a seemingly uncontrollable, self-destructive world. In Europe in the 1970s, new playwriting was largely overshadowed by theatricalist productions, which generally took classical plays and reinterpreted them, often in bold new scenographic spectacles, expressing ideas more through action and the use of space than through language. In the late 1970s a return to Naturalism in drama paralleled the art movement known as Photorealism. Typified by such plays as American Buffalo (1976) by David Mamet, little action occurs, the focus is on mundane characters and events, and language is fragmentary-much like everyday conversation. The settings are indistinguishable from reality. The intense focus on seemingly meaningless fragments of reality creates an absurdist, nightmarish quality: similar traits can be found in writers such as Stephen Poliakoff. A gritty social realism combined with very dark humour has also been popular; it can be seen in the very different work of Alan Ayckbourn, Mike Leigh, Michael Frayn, Alan Bleasdale, and Dennis Potter. In all lands where the drama flourishes, the only constant factor today is what has always been constant: change. The most significant writers are still those who seek to redefine the basic premises of the art of drama. Medieval theatre refers to the theatre of Europe between the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century A.D. and the beginning of the Renaissance in approximately the 15th century A.D. Medieval theatre covers all drama produced in Europe over that thousand year period and refers to a variety of genres, including liturgical drama, mystery plays, morality plays, farces and masques. Beginning with Hrosvitha of Gandersheim in the 10th century, Medieval drama was for the most part very religious and moral in its themes, staging and traditions. The most famous examples of medieval plays are the English cycle dramas, the York Mystery Plays, the Chester Mystery Plays, the Wakefield Mystery Plays and the N-Town Plays, as well as the morality play, Everyman. Due to a lack of surviving records and texts, a low literacy rate of the general population, and the opposition of the clergy to some types of performance, there are few surviving sources on medieval drama of the early and high medieval periods. However, by the late period, drama and theatre began to become more secularized and a larger number of records survive documenting plays and performances. Transition from Rome, 500-900 A.D. As the Western Roman Empire fell into decay through the 4th and 5th centuries A.D., the seat of Roman power shifted to Constantinople and the Eastern Roman Empire, today called the Byzantine Empire. While surviving evidence about Byzantine theatre is slight, existing records show that mime, pantomime, scenes or recitations from tragedies and comedies, dances, and other entertainments were very popular. Constantinople had two theatres that were in use as late as the 5th century A.D. However, the true importance of the Byzantines in theatrical history is their preservation of many classical Greek texts and the compilation of a massive encyclopedia called the Suda, from which is derived a large amount of contemporary information on Greek theatre.[1] In the 6th century, the Emporer Justinian finally closed down all theatres for good. According to the binary thinking of the Church's early followers, everything that did not belong to God belonged to the Devil; thus all nonChristian gods and religions were satanic. Efforts were made in many countries through this period to not only convert Jews, pagans and Muslims but to destroy pre-Christian institutions and influences. Works of Greek and Roman literature were burnt, the thousand-year-old Platonic Academy was closed, the Olympic games were banned and all theatres were shut down. The theatre itself was viewed as a diabolical threat to Christianity because of its continued popularity in Rome even among new converts. Church fathers such as Tatian, Tertullian and Augustine characterized the stage as instruments in the devil's fiendish plot to corrupt men's souls, while acting was considered sinful because of it's cruel mockery of God's creation.[2]

Under these influences, the Church set about trying to suppress theatrical spectacles by passing laws prohibiting and excluding Roman actors. They were forbidden to have contact with Christian women, own slaves, or wear gold. They were officially excommunicated, denied the sacraments, including marriage and burial, and were defamed and debased throughout Europe. For many centuries thereafter, clerics were cautioned to not allow these suddenly homeless, travelling actors to perform in their jurisdictions. [2] From the 5th century, Western Europe was plunged into a period of general disorder that lasted (with a brief period of stability under the Carolingian Empire in the 9th century) until the 10th century A.D. As such, most organized theatrical activities disappeared in Western Europe. While it seems that small nomadic bands traveled around Europe throughout the period, performing wherever they could find an audience, there is no evidence that they produced anything but crude scenes.[3] Early Medieval Period Faced with the problem of explaining a new religion to a largely illiterate population, churches in the early Middle Ages began staging dramatized versions of particular biblical events on specific days of the year. These dramatizations were included in order to vivify annual celebrations. [4] Symbolic objects and actions - vestments, altars, censers, and pantomime performed by priests - recalled the events which Christian ritual celebrates. These were extensive sets of visual signs that could be used to communicate with a largely illiterate audience. These performances developed into liturgical dramas, the earliest of which is the Whom do you Seek (Quem-Quaeritis) Easter trope, dating from ca. 925.[5] Liturgical drama was sung responsively by two groups and did not involve actors impersonating characters. However, sometime between 965 and 975, thelwold of Winchester composed the Regularis Concordia (Monastic Agreement) which contains a playlet complete with directions for performance.[6] Hrosvitha (c.935-973), an aristocratic canoness and historian in northern Germany, wrote six plays modeled on Terence's comedies but using religious subjects in the 10th century A.D. Terence's comedies had long been used in monastery schools as examples of spoken Latin but are full of clever, alluring courtesans and ordinary human pursuits such as sex, love and marriage. In order to preempt criticism from the Church, Hrosvitha prefaced her collection by stating that her moral purpose to save Christians from the guilt they must feel when reading Classical literature. Her declared solution was to imitate the "laudable" deeds of women in Terence's plays and discard the "shameless" ones.[7] These six plays are the first known plays composed by a female dramatist and the first identifiable Western dramatic works of the post-classical era.[6] They were first published in 1501 and had considerable influence on religious and didactic plays of the sixteenth century. Hrosvitha was followed by Hildegard of Bingen (d. 1179), a Benedictine abbess, who wrote a Latin musical drama called Ordo Virtutum in 1155. The anonymous pagan play "Querolus", written c.420, was adapted in the 12th century by Vitalis of Blois. Other secular Latin plays were also written in the 12th century, mainly in France but also in England ("Babio"). There certainly existed some other performances that were not fully fledged theatre; they may have been carryovers from the original pagan cultures (as is known from records written by the clergy disapproving of such festivals). It is also known that mimes, minstrels, bards, storytellers, and jugglers traveled in search of new audiences and financial support. Not much is known about these performers' repertoire and few written texts survive. One of the most famous of the secular plays is the musical "Le Jeu de Robin et Marion", written by Adam de la Halle in the 13th century, which is fully laid out in the original manuscript with lines, musical notation, and illuminations in the margins depicting the actors in motion. Adam also wrote another secular play, "Jeu de la Fueillee" in Arras, a French town in which theatre was thriving in the late 12th and 13th centuries. Perhaps the finest play surviving from Arras, is the "Jeu de saint Nicolas" by Jean Bodel (c.1200). High and Late Medieval Theatre As the Viking invasions ceased in the middle of the 11th century A.D., liturgical drama had spread from Russia to Scandinavia to Italy. Only in Muslim-occupied Spain were liturgical dramas not presented at all. Despite the large number of liturgical dramas that have survived from the period, many churches would have only performed one or two per year and a larger number never performed any at all. [8] The Feast of Fools was especially important in the development of comedy. The festival inverted the status of the lesser clergy and allowed them to ridicule their superiors and the routine of church life. Sometimes plays were staged as part of the occasion and a certain amount of burlesque and comedy crept into these performances. Although comic episodes had to truly wait until the separation of drama from the liturgy, the Feast of Fools undoubtedly had a profound effect on the development of comedy in both religious and secular plays. [9] Performance of religious plays outside of the church began sometime in the 12th century through a traditionally accepted process of merging shorter liturgical dramas into longer plays which were then translated into vernacular and performed by laymen. The Mystery of Adam (1150) gives credence to this theory as its detailed stage direction suggest that it was staged outdoors. A number of other plays from the period survive, including La Seinte Resurrection (Norman), The Play of the Magi Kings (Spanish), and Sponsus (French). The importance of the High Middle Ages in the development of theatre was the economic and political changes that led to the formation of guilds and the growth of towns. This would lead to significant changes in the Late Middle Ages. In the British Isles, plays were produced in some 127 different towns during the Middle Ages. These vernacular Mystery plays were written in cycles of a large number of plays: York (48 plays), Chester (24), Wakefield (32) and Unknown (42). A larger number of plays survive from France and Germany in this period and some type of religious dramas were performed in nearly every European country in the Late Middle Ages. Many of these plays contained comedy, devils, villains and clowns.[10]

The majority of actors in these plays were drawn from the local population. For example, at Valenciennes in 1547, more than 100 roles were assigned to 72 actors.[11] Plays were staged on pageant wagon stages, which were platforms mounted on wheels used to move scenery. Often providing their own costumes, amateur performers in England were exclusively male, but other countries had female performers. The platform stage, which was an unidentified space and not a specific locale, allowed for abrupt changes in location. Morality plays emerged as a distinct dramatic form around 1400 and flourished until 1550. The most interesting morality play is The Castle of Perseverance which depicts mankind's progress from birth to death. However, the most famous morality play and perhaps best known medieval drama is Everyman. Everyman receives Death's summons, struggles to escape and finally resigns himself to necessity. Along the way, he is deserted by Kindred, Goods, and Fellowship - only Good Deeds goes with him to the grave. There were also a number of secular performances staged in the Middle Ages, the earliest of which is The Play of the Greenwood by Adam de la Halle in 1276. It contains satirical scenes and folk material such as faeries and other supernatural occurrences. Farces also rose dramatically in popularity after the 13th century. The majority of these plays come from France and Germany and are similar in tone and form, emphasizing sex and bodily excretions.[12] The best known playwright of farces is Hans Sachs (1494-1576) who wrote 198 dramatic works. In England, the The Second Shepherds' Play of the Wakefield Cycle is the best known early farce. However, farce did not appear independently in England until the 16th century with the work of John Heywood (1497-1580). A significant forerunner of the development of Elizabethan drama was the Chambers of Rhetoric in the Low Countries.[13] These societies were concerned with poetry, music and drama and held contests to see which society could compose the best drama in relation to a question posed. At the end of the Late Middle Ages, professional actors began to appear in England and Europe. Richard III and Henry VII both maintained small companies of professional actors. Their plays were performed in the Great Hall of a nobleman's residence, often with a raised platform at one end for the audience and a "screen" at the other for the actors. Also important were Mummers' plays, performed during the Christmas season, and court masques. These masques were especially popular during the reign of Henry VIII who had a House of Revels built and an Office of Revels established in 1545.[14] Staging Depending on the area of the performances, the plays were performed in the middle of the street, on pageant wagons in the streets of great cities (this was inconvenient for the actors because the small stage size made stage movement impossible), in the halls of nobility, or in the round in amphitheatres, as suggested by current archaeology in Cornwall and the southwest of England. All medieval stage production was temporary and expected to be removed upon the completion of the performances. Actors, predominantly male, typically wore long, dark robes. Medieval plays such as the Wakefield cycle, or the Digby Magdalene featured lively interplay between two distinct areas, the wider spaces in front of the raised staging areas, and the elevated areas themselves (called, respectively, the locus and the platea).[15] Typically too, actors would move between these locations in order to suggest scene changes, rather than remain stationary and have the scene change around them as is typically done in modern theater. [edit] Decline and Change Its death was due mostly to changing political and economic factors. First, the Protestant Reformation targeted the theatre, especially in England, in an effort to stamp out allegiance to Rome. In Wakefield, for example, the local mystery cycle text shows signs of Protestant editing, with references to the pope crossed out and two plays completely eliminated because they were too Catholic. However, it was not just the Protestants who attacked the theatre of the time. The Council of Trent banned religious plays in an attempt to rein in the extrabiblical material that the Protestants frequently lampooned. A revival of interest in ancient Roman and Greek culture changed the tastes of the learned classes in the performing arts. Greek and Roman plays were performed and new plays were written that were heavily influenced by the classical style. This led to the creation of Commedia dell'arte and other forms of Renaissance theatre. A change of patronage also caused drastic changes to the theatre. In England the monarch and nobility started to support professional theatre troupes (including Shakespeare's Lord Chamberlain's Men and King's Men), which catered to their upper class patron's tastes. These patrons desired to be entertained, not preached to, and as time passed the plays became more secular and refined. In time these same tastes would filter down to the lower classes. Finally, the construction of permanent theaters, such as the Blackfriars Theatre signaled a major turning point from reliance on church facilities, touring groups, and inns as stages. Permanent theaters allowed for more sophisticated staging and storytelling. Moreover, professional troupes that owned their own theatre had more resources with which to prepare their productions, which changed the theatre from a mostly amateur or traveling art form to a professional one with different practices and standards. English Renaissance theatre, also known as early modern English theatre, refers to the theatre of England, largely based in London, which occurred between the Reformation and the closure of the theatres in 1642. It includes the drama of William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe and many other famous playwrights.

Contents [show]

Background Renaissance theatre derived from medieval theatre traditions, such as the mystery plays that formed a part of religious festivals in England and other parts of Europe during the Middle Ages. The mystery plays were complex retellings of legends based on biblical themes, originally performed in Cathedrals, but later becoming more linked to the secular celebrations that grew up around religious festivals. Other sources include the morality plays and the "University drama" that attempted to recreate Greek tragedy. The Italian tradition of commedia dell'arte as well as the elaborate masques frequently presented at court also contributed to the shaping of public theatre. Companies of players attached to households of leading noblemen and performing seasonally in various locations existed before the reign of Elizabeth I. These became the foundation for the professional players that performed on the Elizabethan stage. The tours of these players gradually replaced the performances of the mystery and morality plays by local players, and a 1572 law eliminated the remaining companies lacking formal patronage by labeling them vagabonds. The performance of masques at court by courtiers and other amateurs came to be replaced by the professional companies with noble patrons, who grew in number and quality during Elizabeth's reign. The City of London authorities were generally hostile to public performances, but its hostility was overmatched by the Queen's taste for plays and the Privy Council's support. Theatres sprang up in suburbs, especially in the liberty of Southwark, accessible across the Thames to city dwellers, but beyond the authority's control. The companies maintained the pretence that their public performances were mere rehearsals for the frequent performances before the Queen, but while the latter did grant prestige, the former were the real source of the income professional players required. Along with the economics of the profession, the character of the drama changed toward the end of the period. Under Elizabeth, the drama was a unified expression as far as social class was concerned: the Court watched the same plays the commoners saw in the public playhouses. With the development of the private theatres, drama became more oriented toward the tastes and values of an upper-class audience. By the later part of the reign of Charles I, few new plays were being written for the public theatres, which sustained themselves on the accumulated works of the previous decades.[1] Theatres The establishment of large and profitable public theatres was an essential enabling factor in the success of English Renaissance drama. Once they were in operation, drama could become a fixed and permanent rather than a transitory phenomenon. Their construction was prompted when the Mayor and Corporation of London first banned plays in 1572 as a measure against the plague, and then formally expelled all players from the city in 1575.[2] This prompted the construction of permanent playhouses outside the jurisdiction of London, in the liberties of Halliwell/Holywell in Shoreditch and later the Clink, and at Newington Butts near the established entertainment district of St. George's Fields in rural Surrey.[2] The Theatre was constructed in Shoreditch in 1576 by James Burbage with his brother-in-law John Brayne (the owner of the unsuccessful Red Lion playhouse of 1567)[3] and the Newington Butts playhouse was set up, probably by Jerome Savage, some time between 1575[4] and 1577.[5] The Theatre was rapidly followed by the nearby Curtain Theatre (1577), the Rose (1587), the Swan (1595), the Globe (1599), the Fortune (1600), and the Red Bull (1604).[6] Archaeological excavations on the foundations of the Rose and the Globe in the late twentieth century showed that all the London theatres had individual differences; yet their common function necessitated a similar general plan.[7] The public theatres were three stories high, and built around an open space at the centre. Usually polygonal in plan to give an overall rounded effect (though the Red Bull and the first Fortune were square), the three levels of inward-facing galleries overlooked the open center, into which jutted the stageessentially a platform surrounded on three sides by the audience, only the rear being restricted for the entrances and exits of the actors and seating for the musicians. The upper level behind the stage could be used as a balcony, as in Romeo and Juliet or Antony and Cleopatra, or as a position from which an actor could harangue a crowd, as in Julius Caesar.[citation needed] Usually built of timber, lath and plaster and with thatched roofs, the early theatres were vulnerable to fire, and were replaced (when necessary) with stronger structures. When the Globe burned down in June 1613, it was rebuilt with a tile roof; when the Fortune burned down in December 1621, it was rebuilt in brick (and apparently was no longer square).[citation needed] A different model was developed with the Blackfriars Theatre, which came into regular use on a long-term basis in 1599.[8] The Blackfriars was small in comparison to the earlier theatres and roofed rather than open to the sky; it resembled a modern theatre in ways that its predecessors did not. Other small enclosed theatres followed, notably the Whitefriars (1608) and the Cockpit (1617). With the building of the Salisbury Court Theatre in 1629 near the site of the defunct Whitefriars, the London audience had six theatres to choose from: three surviving large open-air "public" theatres, the Globe, the Fortune, and the Red Bull, and three smaller enclosed "private" theatres, the Blackfriars, the Cockpit, and the Salisbury Court.[9] Audiences of the 1630s benefited from a half-century of vigorous dramaturgical development; the plays of Marlowe and Shakespeare and their contemporaries were still being performed on a regular basis (mostly at the public theatres), while the newest works of the newest playwrights were abundant as well (mainly at the private theatres).[citation needed]

Around 1580, when both the Theatre and the Curtain were full on summer days, the total theatre capacity of London was about 5000 spectators. With the building of new theatre facilities and the formation of new companies, the capital's total theatre capacity exceeded 10,000 after 1610.[10] In 1580, the poorest citizens could purchase admittance to the Curtain or the Theatre for a penny; in 1640, their counterparts could gain admittance to the Globe, the Cockpit, or the Red Bullfor exactly the same price.[citation needed] (Ticket prices at the private theatres were five or six times higher).[citation needed] Performances The acting companies functioned on a repertory system; unlike modern productions that can run for months or years on end, the troupes of this era rarely acted the same play two days in a row. Thomas Middleton's A Game at Chess ran for nine straight performances in August 1624 before it was closed by the authoritiesbut this was due to the political content of the play and was a unique, unprecedented, and unrepeatable phenomenon. Consider the 1592 season of Lord Strange's Men at the Rose Theatre as far more representative: between Feb. 19 and June 23 the company played six days a week, minus Good Friday and two other days. They performed 23 different plays, some only once, and their most popular play of the season, The First Part of Hieronimo, (based on Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy), 15 times. They never played the same play two days in a row, and rarely the same play twice in a week.[11] The workload on the actors, especially the leading performers like Edward Alleyn, must have been tremendous. One distinctive feature of the companies was that they included only males. Until the reign of Charles II, female parts were played by adolescent boy players in women's costume. Costumes Costumes were often bright in color and visually entrancing. Costumes were expensive, however, so usually players wore contemporary clothing regardless of the time period of the play. Occasionally, a lead character would wear a conventionalized version of more historically accurate garb, but secondary characters would nonetheless remain in contemporary clothing. Playwrights The growing population of London, the growing wealth of its people, and their fondness for spectacle produced a dramatic literature of remarkable variety, quality, and extent. Although most of the plays written for the Elizabethan stage have been lost, over 600 remain. The men (no women were professional dramatists in this era) who wrote these plays were primarily self-made men from modest backgrounds.[12] Some of them were educated at either Oxford or Cambridge, but many were not. Although William Shakespeare and Ben Jonson were actors, the majority do not seem to have been performers, and no major author who came on to the scene after 1600 is known to have supplemented his income by acting. Not all of the playwrights fit modern images of poets or intellectuals. Christopher Marlowe was killed in an apparent tavern brawl, while Ben Jonson killed an actor in a duel. Several probably were soldiers. Playwrights were normally paid in increments during the writing process, and if their play was accepted, they would also receive the proceeds from one day's performance. However, they had no ownership of the plays they wrote. Once a play was sold to a company, the company owned it, and the playwright had no control over casting, performance, revision or publication. The profession of dramatist was challenging and far from lucrative.[13] Entries in Philip Henslowe's Diary show that in the years around 1600 Henslowe paid as little as 6 or 7 per play. This was probably at the low end of the range, though even the best writers could not demand too much more. A playwright, working alone, could generally produce two plays a year at most; in the 1630s Richard Brome signed a contract with the Salisbury Court Theatre to supply three plays a year, but found himself unable to meet the workload. Shakespeare produced fewer than 40 solo plays in a career that spanned more than two decades; he was financially successful because he was an actor and, most importantly, a shareholder in the company for which he acted and in the theatres they used. Ben Jonson achieved success as a purveyor of Court masques, and was talented at playing the patronage game that was an important part of the social and economic life of the era. Those who were playwrights pure and simple fared far less well; the biographies of early figures like George Peele and Robert Greene, and later ones like Brome and Philip Massinger, are marked by financial uncertainty, struggle, and poverty. Playwrights dealt with the natural limitation on their productivity by combining into teams of two, three, four, and even five to generate play texts; the majority of plays written in this era were collaborations, and the solo artists who generally eschewed collaborative efforts, like Jonson and Shakespeare, were the exceptions to the rule. Dividing the work, of course, meant dividing the income; but the arrangement seems to have functioned well enough to have made it worthwhile. (The truism that says, diversify your investments, may have worked for the Elizabethan play market as for the modern stock market.) Of the 70-plus known works in the canon of Thomas Dekker, roughly 50 are collaborations; in a single year, 1598, Dekker worked on 16 collaborations for impresario Philip Henslowe, and earned 30, or a little under 12 shillings per weekroughly twice as much as the average artisan's income of 1s. per day.[14] At the end of his career, Thomas Heywood would famously claim to have had "an entire hand, or at least a main finger" in the authorship of some 220 plays. A solo artist usually needed months to write a play (though Jonson is said to have done Volpone in five weeks); Henslowe's Diary indicates that a team of four or five writers could produce a play in as little as two weeks. Admittedly, though, the Diary also shows that teams of Henslowe's house dramatistsAnthony Munday, Robert Wilson, Richard Hathwaye, Henry Chettle, and the others, even including a young John Webstercould start a project, and accept advances on it, yet fail to

produce anything stageworthy. (Modern understanding of collaboration in this era is biased by the fact that the failures have generally disappeared with barely a trace; for one exception to this rule, see: Sir Thomas More.)[15]. Most playwrights, like Shakespeare for example, wrote in verse. Genres Genres of the period included the history play, which depicted English or European history. Shakespeare's plays about the lives of kings, such as Richard III and Henry V, belong to this category, as do Christopher Marlowe's Edward II and George Peele's Famous Chronicle of King Edward the First. History plays dealt with more recent events, like A Larum for London which dramatizes the sack of Antwerp in 1576. Tragedy was a popular genre. Marlowe's tragedies were exceptionally popular, such as Dr. Faustus and The Jew of Malta. The audiences particularly liked revenge dramas, such as Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy. The four tragedies considered to be Shakespeare's greatest (Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth) were composed during this period, as well as many others (see Shakespearean tragedy). Comedies were common, too. A sub-genre developed in this period was the city comedy, which deals satirically with life in London after the fashion of Roman New Comedy. Examples are Thomas Dekker's The Shoemaker's Holiday and Thomas Middleton's A Chaste Maid in Cheapside. Though marginalised, the older genres like pastoral (The Faithful Shepherdess, 1608), and even the morality play (Four Plays in One, ca. 160813) could exert influences. After about 1610, the new hybrid sub-genre of the tragicomedy enjoyed an efflorescence, as did the masque throughout the reigns of the first two Stuart kings, James I and Charle

Elizabethan Theatre Elizabethan theatre and the name of William Shakespeare are inextricably bound together, yet there were others writing plays at the same time as the bard of Avon. One of the most successful was Christopher Marlowe, who many contemporaries considered Shakespeare's superior. Marlowe's career, however, was cut short at a comparatively young age when he died in a tavern fight in Deptford, the victim of a knife in the eye. Theatre had an unsavory reputation. London authorities refused to allow plays within the city, so theatres opened across the Thames in Southwark, outside the authority of the city administration. The first proper theatre as we know it was the Theatre, built at Shoreditch in 1576. Before this time plays were performed in the courtyard of inns, or sometimes, in the houses of noblemen. A noble had to be careful about which play he allowed to be performed within his home, however. Anything that was controversial or political was likely to get him in trouble with the crown! After the Theatre, further open air playhouses opened in the London area, including the Rose (1587), and the Hope (1613). The most famous playhouse was the Globe (1599) built by the company in which Shakespeare had a stake. The Globe was only in use until 1613, when a canon fired during a performance of Henry VIII caught the roof on fire and the building burned to the ground. The site of the theatre was rediscovered in the 20th century and a reconstruction built near the spot.

Shakespeare

These theatres could hold several thousand people, most standing in the open pit before the stage, though rich nobles could watch the play from a chair set on the side of the stage itself. Theatre performances were held in the afternoon, because, of course, there was no artificial lighting. Women attended plays, though often the prosperous woman would wear a mask to disguise her identity. Further, no women performed in the plays. Female roles were generally performed by young boys.

18th century theatre Rationalism Restoration comedy, an aristocratic and seemingly amoral form of theatre, declined, at least in part because of the rise of a conservative Protestant (Puritan) middle class.

Such works as Jeremy Colliers 1698 A Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage helped lead popular sentiment against the Restoration theatre. During the 1700s, the concept of Rationalism (The Age of Reason), faith in reason, began to take over from faith in God Rationalism begins to lead away from the strict rules of Neoclassicism. This comes from a faith in man. Part of this led to the movement of Sentimentalism in the theatre. asserted that each person was essentially good. Sentimentalism Sentimentalism: characterized by an over-emphasis on arousing sympathetic responses to misfortune. Begins in England, 1690s to 1730s. Resulted in Sentimental Comedies / tearful comedies: more conservative, middle-class, sentimental, moralistic. Sir Richard Steele (1672-1729) sought to arouse noble sentimentswanted a "pleasure too exquisite for laughter." The Conscious Lovers (1722) sentimental comedy with protagonists drawn from the middle class. The heroine, Indiana, after many trials, is discovered to be the daughter of a rich merchant so she can marry, and thus a happy resolution. Servants have some funny scenes. The 18th century view held that people are good; their instincts let them retain goodness. People could retain virtue by appealing to virtuous human feelings. Oliver Goldsmith (1731-1774) -- wrote "laughing comedies" sentimental comedies intended to make people laugh ?? She Stoops to Conquer (1773) mistaken identities, benign trickery, keep two lovers apart. Richard Sheridan The Rivals (1775 Mrs. Malaprop was a character). School for Scandal (1777) Serious Drama in the 18th Century: Joseph Addison (1672-1719) Cato (1713) is considered a masterpiece. Heroic Tragedy: Written in "heroic verse," which used "couplets," verses of iambic pentameter that are rhymed; it was an attempt to reproduce the French "Alexandrine" verse, which used 12 syllables per line and has no equivalent in English. Dealt with conflicts between love and honor or duty, contained violent action, were melodramatic (the heroes were flawless and the heroines chaste). These eventually declined in public favor they were easily ridiculed and parodied. Became replaced with more Neoclassical plays, such as: John Dryden (1631-1700) All for Love a reworking of Shakespeares Antony and Cleopatra, with neoclassical ideals. Other 18th Century Forms: Ballad Opera sections of dialog alternating with lyrics set to popular tunes. John Gays The Beggars Opera (1728) satirized British politics, using Georg Frederick Handels Messiah and other tunes,

A precursor to musical comedy. Farce was also popular. Henry Fielding was popular in the 1730s. Pantomimes became popular by 1715 combined dancing, mime (silent mimicry), done to music, with elaborate scenery and special effects done as an afterpiece after plays. They combined commedia, farce, mythology. The Harlequin came from these pantomimes with his magic wand, the scenery would change. Primarily visual and aural entertainment. Because the scenery was commissioned, there was often innovative scenery.

Staging in the 18th Century Theatre Generally Italianate, but English theatres used a forestage the apron. Two doors were in the proscenium opening on to the apron. Most of the acting was done on the forestage. The apron had been as large as the stage space, but by 1750, it was back to being as small as in Italy and France. Theatres increased in size: from seating 650 people during the Restoration to 1500 people by 1750. The stage jutted out into the pit, there were still galleries and boxes (private galleries). Grooves were installed in the rakes stages. Usually stock sets were used, lit by candle-light, costumes were elaborate and contemporary.

Most Revolutionary Change!!: Women on stage! Acting companies used women for all female parts except witched and old women. It was common for "lines of business" to emerge: the kind of role one would play and seldom stray from. Many companies used "possession of parts": an agreement that when an actor joins a company he "owns" a particular role. This led to traditionalism and conservatism. Vocal power and versatility seemed to be essential. "Playing for points" was common: getting applause and doing an encore after particular speeches; as you can imagine, this wasnt very realistic. Some acting companies shared salaries, playing "benefits" to earn up to a years salary (the opposite of what a "benefit" is today). The "repertory" system was common: rotating a large number of plays.

Nineteenth-century theatre describes a wide range of movements in the theatrical culture of Europe and the United States in the 19th century. In the West, they include Romanticism, melodrama, the well-made plays of Scribe and Sardou, the farces of Feydeau, the problem plays of Naturalism and Realism, Several important technical innovations were introduced between 1875 and 1914. First gas lighting and then electric lights, introduced in London's Savoy Theatre in 1881, replaced candlelight. The elevator stage was first installed in the Budapest Opera House in 1884. This allowed entire sections of the stage to be raised, lowered, or tilted to give depth and levels to the scene. The revolving stage was introduced to Europe by Karl Lautenschlger at the Residenz Theatre, Munich in 1896. Beginning in France after the theatre monopolies were abolished in 1791 during the French Revolution, melodrama became the most popular theatrical form. Although monopolies and subsidies were reinstated under Napoleon, it continued to be extremely popular and brought in larger audiences than the state-sponsored drama and operas. Although melodrama can can be traced back to classical Greece, the term mlodrame did not appear until 1766 and only became popular after 1800. August von Kotzebue's Misanthropy and Repentance (1789) is often considered the first melodramatic play. The plays of Kotzebue and Ren Charles Guilbert de Pixrcourt established melodrama as the dominant dramatic form of the early 19th century.[2] David Grimsted, in his book Melodrama Unveiled (1968), argues that: Its conventions were false, its language stilted and commonplace, its characters stereotypes, and its morality and theology gross simplifications. Yet its appeal was great and understandable. It took the lives of common people seriously and paid much respect to their superior purity and wisdom. [...] And its moral parable struggled to reconcile social fears and life's awesomeness with the period's confidence in absolute moral standards, man's upward progress, and a benevolent providence that insured the triumph of the pure.[3] In Paris, the 19th century saw a flourishing of melodrama in the many theatres that were located on the popular Boulevard du Crime, especially in the Gat. All this was to come to an end, however, when most of these theatres were demolished during the rebuilding of Paris by Baron Haussmann in 1862.[4] By the end of the 19th century, the term melodrama had nearly exclusively narrowed down to a specific genre of salon entertainment: more or less rhythmically spoken words (often poetry)not sung, sometimes more or less enacted, at least with some dramatic structure or plot synchronized to an accompaniment of music (usually piano). It was looked down on as a genre for authors and composers of lesser stature (probably also the reason why virtually no realisations of the genre are still remembered). Realism began earlier in the 19th century in Russia than elsewhere in Europe and took a more uncompromising form.[14] Beginning with the plays of Ivan Turgenev (who used "domestic detail to reveal inner turmoil"), Aleksandr Ostrovsky (who was Russia's first professional playwright), Aleksey Pisemsky (whose A Bitter Fate (1859) anticipated Naturalism), and Leo Tolstoy (whose The Power of Darkness (1886) is "one of the most effective of naturalistic plays"), a tradition of psychological realism in Russia culminated with the establishment of the Moscow Art Theatre by Constantin Stanislavski and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko.[15] Ostrovsky is often credited with creating a peculiarly Russian drama. His plays Enough Stupidity in Every Wise Man (1868) and The Storm (1859) draw on the life that he knew best, that of the middle class. Other important Russian playwrights of the 19th century include Alexander Sukhovo-Kobylin and Mikhail Saltikov-Shchedrin.. Naturalism, a theatrical movement born out of Charles Darwin's The Origin of Species (1859) and contemporary political and economic conditions, found its main proponent in mile Zola. His essay "Naturalism in the Theatre" (1881) argued that poetry is everywhere instead of in the past or abstraction: "There is more poetry in the little apartment of a bourgeois than in all the empty worm-eaten palaces of history." The realisation of Zola's ideas was hindered by a lack of capable dramatists writing naturalist drama. Andr Antoine emerged in the 1880s with his Thtre Libre that was only open to members and therefore was exempt from censorship. He quickly won the approval of Zola and began to stage Naturalistic works and other foreign realistic pieces. Antoine was unique in his set design as he built sets with the "fourth wall" intact, only deciding which wall to remove later. The most important French playwrights of this period were given first hearing by Antoine including Georges Porto-Riche, Franois de Curel, and Eugne Brieux.[16] The work of Henry Arthur Jones and Arthur Wing Pinero initiated a new direction on the English stage. While their work paved the way, the development of more significant drama owes itself most to the playwright Henrik Ibsen. Ibsen was born in Norway in 1828. He wrote twenty-five plays, the most famous of which are A Doll's House (1879), Ghosts (1881), The Wild Duck (1884), and Hedda Gabler (1890). A Doll's House and Ghosts shocked conservatives: Nora's departure in A Doll's House was viewed as an attack on family and home, while the allusions to venereal disease and sexual misconduct in Ghosts were considered deeply offensive to standards of public decency. Ibsen refined Scribe's well-made play formula to make it more fitting to the realistic style. He provided a model for writers of the realistic school. In addition, his works Rosmersholm (1886) and When We Dead Awaken (1899) evoke a sense of mysterious forces at work in human destiny, which was the be a major theme of symbolism and the so-called "Theatre of the Absurd". After Ibsen, British theatre experienced revitalization with the work of George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, John Galsworthy, William Butler Yeats, and Harley Granville Barker. Unlike most of the gloomy and intensely serious work of their contemporaries, Shaw and Wilde wrote primarily in the comic form.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Medieval TheatreDocument12 pagesMedieval TheatreNati DurePas encore d'évaluation

- French FarceDocument13 pagesFrench FarceJames-Michael Evatt100% (1)

- Theatre HistoryDocument27 pagesTheatre Historyj_winter2Pas encore d'évaluation

- 4th ARTS 9 18 19Document12 pages4th ARTS 9 18 19Konoha MaruPas encore d'évaluation

- Medieval TheatreDocument28 pagesMedieval TheatreAngelly V Velasco100% (1)

- History of Medieval DramaDocument9 pagesHistory of Medieval DramaManoj KanthPas encore d'évaluation

- Emergency Lesson Plan Medieval TheatreDocument4 pagesEmergency Lesson Plan Medieval TheatreAnonymous AtJitx3W100% (1)

- Comparison Greek Medieval Renaissance2Document14 pagesComparison Greek Medieval Renaissance2hazePas encore d'évaluation

- A Brief History of Theatre Architecture and StageDocument53 pagesA Brief History of Theatre Architecture and StageAnca Hatiegan0% (1)

- History and Development of DramaDocument63 pagesHistory and Development of DramaMahi Mughal100% (2)

- Medieval DramaDocument10 pagesMedieval DramaJason DiGiulioPas encore d'évaluation

- Arts9 q4 Mod1 TheatricalForms v4Document24 pagesArts9 q4 Mod1 TheatricalForms v4lj balinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Theatre of The 20th Century and BeyondDocument7 pagesTheatre of The 20th Century and BeyondGilda MoPas encore d'évaluation

- Murakami I 112005Document445 pagesMurakami I 112005Jazmin-ArabePas encore d'évaluation

- Medieval Theatre: History of Theatre 900-1500 ADDocument26 pagesMedieval Theatre: History of Theatre 900-1500 ADRexPas encore d'évaluation

- Arts9 Q4 M1-4Document12 pagesArts9 Q4 M1-4Radleigh Vesarius RiegoPas encore d'évaluation

- Theatre History Fall 2020 SyllabusDocument9 pagesTheatre History Fall 2020 SyllabusCelinna Abigail RiordanPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Theater. Eng 119 Enrichment Module 6Document17 pagesHistory of Theater. Eng 119 Enrichment Module 6Lianne Grace Basa BelicanoPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 - Introduction To English DramaDocument9 pages7 - Introduction To English Dramarawan samiPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL Week 1 Arts 9 4TH QuarterDocument5 pagesDLL Week 1 Arts 9 4TH QuarterAdhing ManolisPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - The History and Rise of Professional TheatreDocument6 pages1 - The History and Rise of Professional TheatreIvanPas encore d'évaluation

- Medieval TheatreDocument31 pagesMedieval TheatreLea nessa OrnedoPas encore d'évaluation

- Medieval Drama Harsh 2016 Eng CIADocument3 pagesMedieval Drama Harsh 2016 Eng CIAHarsh BohraPas encore d'évaluation

- Gallo 2017, Jesuit TheaterDocument28 pagesGallo 2017, Jesuit TheaterfusonegroPas encore d'évaluation

- Development of TheaterDocument36 pagesDevelopment of TheaterYhesa PagadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Circular TMA 103 NoteDocument7 pagesCircular TMA 103 NoteSodunke Samuel100% (1)

- Day 1 Theatrical Forms From Different Art Periods. (Day 1&2Document38 pagesDay 1 Theatrical Forms From Different Art Periods. (Day 1&2bonitdanilo1968Pas encore d'évaluation

- Arts9 q4 Mod1 Theatricalforms v5Document30 pagesArts9 q4 Mod1 Theatricalforms v5Harold RicafortPas encore d'évaluation

- Theater Arts 1Document39 pagesTheater Arts 1Sabria Franzielle MallariPas encore d'évaluation

- Medieval DramaDocument5 pagesMedieval Dramaarek52Pas encore d'évaluation