Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Descartes' Rationalism: Rational Intuition

Transféré par

Trung TungDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Descartes' Rationalism: Rational Intuition

Transféré par

Trung TungDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Michael Lacewing

Descar tes r ationalism

Rationalists claim that we have a priori knowledge of synthetic propositions, i.e. knowledge of matters of fact that does not depend upon sense experience. They argue that there are two key ways in which we gain such knowledge: 1. we know certain truths innately, e.g. as part of our rational nature; and/or 2. we have a form of rational intuition or insight which enables us to grasp certain truths intellectually. Descartes is a rationalist in both these ways. Many rationalists add that the synthetic a priori knowledge we gain through reason or innately cannot be arrived at in any other way. They may also argue that is superior, for example by being more certain, to the knowledge or beliefs we gain through the senses. Descartes agrees with this, too. RATIONAL INTUITION Descartes theory of clear and distinct ideas is his account of rational intuition. At the heart of the idea of rational intuition is the view that you can discover the truth of a claim just by thinking about it. The first claim Descartes defends this way is the cogito. He arrives at the cogito by pure reasoning, and we are supposed to recognise that it is true just by considering it. Descartes then goes on to argue that he, as a mind, can exist without having a body. It is therefore possible for minds to exist without bodies. This is a second claim Descartes believes he can establish by a priori reasoning. How do we know about bodies, physical objects? First, how do we know what physical objects are, i.e. what are we talking about? We might say we discover their nature through sense experience. But in the wax argument, Descartes argues that sense experience gives us only a confused idea of physical objects. In fact, we discover what physical objects are by analysing our concept of a physical object. In this way, and not through the senses, we discover that the essential nature of a physical object is to be extended, i.e. to exist in space, with a size, shape and location. Knowing the external world exists Second, how do we know whether bodies do physical objects exist? They cause our experiences, we reply. But using the method of doubt, Descartes first argues that we dont know what causes our experiences it could be a demon. So Descartes must work to once again secure our knowledge of the external world. The argument spans the whole of the Meditations, and takes in arguments about the understanding and the senses, the existence of God, the doctrine of clear and distinct ideas, and human nature. In the handout on The essential natures of mind and body, we discussed Descartes wax example. On its own, this doesnt show that physical objects really are extended. But in Meditation V, Descartes asserts the principle that we can know that what we can clearly

and distinctly conceive is true. So physical objects really are extended, if they exist at all. In Meditation VI, Descartes argues that they do exist, and he seeks to establish that we can and do have knowledge of the physical world, including of course, our own bodies. He first considers whether we can know bodies exist from our imagination. Unlike operations of the intellect, imagination uses images that it has apparently derived from the senses or created for itself, and it requires effort. Both of these features could be explained if we have bodies. So we probably have bodies, but this is hardly a proof. He turns, then, to consider perception. We have experiences which appear, very forcefully, to be experiences of a world external to our minds, whether they are experiences of our own body or of other bodies. These experiences produce ideas without our contribution, i.e. they are involuntary. Among our perceptual experiences are sensations and feelings. We notice that we perceive we have bodies, and that our bodies can be affected in many beneficial and harmful ways, which we experience through our bodily appetites, feelings and emotions. Our faculties of feeling and sensation would seem to be dependent on our having bodies. But, again, this is not a proof. So Descartes considers the matter from another angle. These experiences are involuntary, and if they were caused by our own minds, they would be voluntary. Because we know our own minds, we would know if they were voluntary. So they are not caused by ourselves. They must therefore have some cause which is sufficient to cause them. The options are: a real external world or God. If the cause was God, this would mean that God was a deceiver because He would have created us with a very strong tendency to believe something false. But we know that God is not a deceiver. So there must really be an external world. So what can we know about the external world, having demonstrated that it exists? Descartes argues that God has set us up to learn from nature. Nature teaches us through sensation that we have bodies, and through perception that there are other bodies. This cant simply be the abstract truth that a physical world exists. It must the stronger claim that, in many of our experiences, we are actually confronted with physical objects. Our senses, then, will not be set up so that, with careful employment and the search for clarity and distinctness, they would systematically lead to error. This doesnt mean that any particular belief based on our senses is certain we can still make mistakes. But unless perceptual experience was generally reliable, when we do what we can to avoid error, it would be difficult for Descartes to defend that we can trust what we learn from nature. Descartes offers two arguments, both a priori, for the existence of God one is the Trademark argument and the other is the ontological argument. Since he believes he has demonstrated that God exists, he concludes that we know the external world of physical objects exists. Not because sense experience shows us that it does, but through a priori intuition and reasoning. KNOWING ABOUT THE EXTERNAL WORLD This does not, however, mean that that world is just as perception represents it. First, Descartes does not claim that the external world is as we commonly think it is. His argument has established that the physical world exists and is an extended world. But the

wax argument established that extension and changeability is all that is of the essence of the physical world. Descartes representative realist theory of perception argues that all other properties, of colour, smell, heat, and so on, arent actually properties of physical objects at all, at least not considered on their own. Rather, all I have reason to believe is that there is something in [the external body] which excites in me these feelings (161). We shouldnt think that the something is itself colour, smell, and so on. The external world is a world of geometry, as physical objects only have spatial properties (e.g. size, shape, motion). It is on the basis of its spatial properties that we judge, as in the wax example, that some physical object is in fact present. But we must accept that our particular perceptions of the world are often confused. Gods assurance doesnt mean we are always able to avoid error: because the necessities of action often oblige us to make a decision before we have had the leisure to examine things carefully, it must be admitted that the life of man is very often subject to error in particular cases (168-9). Furthermore, even with caution and recourse to clear and distinct ideas, we can still make mistakes since our nature is fallible. Poor conditions of perception, such as bad light, confused thinking, prejudice, and other factors means that we can make mistakes; this does not make God a deceiver, because these are mistakes we must take responsibility for. INNATE IDEAS In the arguments regarding physical objects and God, Descartes takes the concepts, or ideas, of PHYSICAL OBJECT and GOD for granted. (When referring to a concept, I put the word in capital letters.) Where do these concepts come from? In his Trademark argument for the existence of God, he says there are three possible sources for a concept: that we have invented it (it is fictitious), that it derives from something outside the mind (it is adventitious), or that it is innate. By innate, he doesnt mean we have it from the birth in the sense that a baby can think using this concept. It would be very strange in babies could think about God but didnt yet have a concept of power or reality or love! Innate ideas are ideas that the mind has certain capacities to use, and which cant be explained by our experience. To defend his claim that these ideas (of GOD and PHYSICAL OBJECT) are innate, Descartes needs to show that they cannot be explained by sense experience. And this is what his arguments try to do. Sense experience cannot tell us the essential nature of physical objects; it is an idea that we must use the intellect to analyse. How did it come to be part of the intellect? It is innate. Likewise with GOD. ASSESSING DESCARTES RATIONALISM As we have seen, there are many objections to Descartes arguments. But what do such objections show about Descartes rationalism? Is his method of doing philosophy wrong? Descartes has done his best find what he thinks, using reasoning, is certain. His arguments are supposed to be deductive, and his premises established by rational intuition. But philosophers have still been able to point out unjustified assumptions and inferences. If intuition and deductive reasoning do not give us knowledge, then his rationalism is in trouble. Before we become sceptical about intuition and reasoning, we should ask this: how have philosophers come up with objections to Descartes? It certainly isnt by using sense

experience! So the objections themselves use the same kind of reasoning as Descartes. Only better reasoning, we hope. The objections cannot be objections to the way Descartes reasoned, only objections to the conclusions he drew. But this is too generous, we can argue. Certainly, there is nothing wrong with using deductive reasoning; and we can use it to show that Descartes arguments are faulty. But that doesnt mean we should also accept that there is such a thing as rational intuition or that Descartes theory of clear and distinct ideas is correct. Someone like Hume would argue that we can only perceive the truth of a claim just by thinking about it when that claim is analytic. Our ability to tell that it is truth is not about insight; it is simply because the claim is made true by the meanings of the words it contains. On this view, one reason Descartes arguments fail is because many of his clear and distinct ideas are not analytic, but contain some hidden assumption, and so can be challenged. The certainty Descartes is after can only be found in analytic truths, not through rational intuition. This can all be debated. Do Descartes arguments fail or can he meet the objections? We will have to see. Is he wrong about rational insight? Can we not use a priori reason to discover the truth of (some) synthetic propositions, or is a priori reason limited to analytic truths? Are there any innate ideas?

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Theories of Human RightsDocument3 pagesTheories of Human RightsNazra NoorPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 2 - Recognizing ArgumentsDocument75 pagesChapter 2 - Recognizing ArgumentsPhạm Châu Thuý KiềuPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes on Logic and Critical ThinkingDocument2 pagesNotes on Logic and Critical ThinkingAkif JamalPas encore d'évaluation

- Appraising Analogical ArgumentsDocument23 pagesAppraising Analogical Argumentskisses_dearPas encore d'évaluation

- Special Types of Syllogism ExplainedDocument26 pagesSpecial Types of Syllogism ExplainedLiuricPas encore d'évaluation

- HPHILOGDocument7 pagesHPHILOGHarumiJanePas encore d'évaluation

- Socrates PhilosophyDocument5 pagesSocrates Philosophyapi-232928244Pas encore d'évaluation

- Meta Ethics (Dept Notes)Document11 pagesMeta Ethics (Dept Notes)Julie SucháPas encore d'évaluation

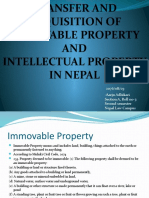

- Transfer and Acquisition of Immovable Property AND Intellectual Property in NepalDocument32 pagesTransfer and Acquisition of Immovable Property AND Intellectual Property in NepalBinita SubediPas encore d'évaluation

- Logic FullDocument6 pagesLogic FullAna EliasPas encore d'évaluation

- The Natural LAW: Amparo, Mercy Cadevida, Ana Morados, Imari Varon, Jessica Villarin, AprilDocument32 pagesThe Natural LAW: Amparo, Mercy Cadevida, Ana Morados, Imari Varon, Jessica Villarin, Aprilmyka.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Vaughn Living Philosophy3e PPT Ch01Document16 pagesVaughn Living Philosophy3e PPT Ch01Edgar Martínez100% (1)

- EthicsDocument31 pagesEthicsALI KAMRANPas encore d'évaluation

- Santos UtilitarianismDocument11 pagesSantos UtilitarianismKyo AmiPas encore d'évaluation

- Symbolic LogicDocument16 pagesSymbolic LogicAnji JoguilonPas encore d'évaluation

- FallacyDocument38 pagesFallacystuartcamensonPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter Four - Critical ThinkingDocument9 pagesChapter Four - Critical Thinkingshumet tadelePas encore d'évaluation

- Truth and Knowledge HandoutDocument6 pagesTruth and Knowledge HandoutMatthew ChenPas encore d'évaluation

- What is Philosophy? Lesson 1Document7 pagesWhat is Philosophy? Lesson 1Erich MagsisiPas encore d'évaluation

- Logic Chapter 3Document15 pagesLogic Chapter 3Hawi Berhanu100% (1)

- Relational HypothesisDocument2 pagesRelational HypothesisFour100% (1)

- LOGIC OF LANGUAGEDocument12 pagesLOGIC OF LANGUAGEZed P. EstalillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reflection Paper: AristotleDocument3 pagesReflection Paper: AristotleJhonmark TemonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Methods of Philosophizing Wk4Document59 pagesMethods of Philosophizing Wk4Lylanie Cadacio Aure100% (1)

- GES 102 Summary-1Document11 pagesGES 102 Summary-1Adachukwu Chioma100% (1)

- Propositions and SyllogismsDocument50 pagesPropositions and Syllogismsviper83% (6)

- Logic Chapter 3Document11 pagesLogic Chapter 3Muhammad OwaisPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter Three: Logic and LanguageDocument16 pagesChapter Three: Logic and LanguageTagayPas encore d'évaluation

- Anselm's Ontological Argument ExplainedDocument8 pagesAnselm's Ontological Argument ExplainedCharles NunezPas encore d'évaluation

- Handout Philo Ancient&Contemporary 07192019Document1 pageHandout Philo Ancient&Contemporary 07192019Harold Lumiguid ArindugaPas encore d'évaluation

- How understanding altruism can boost human kindnessDocument6 pagesHow understanding altruism can boost human kindnessVictoria VioaraPas encore d'évaluation

- AristotleDocument19 pagesAristotleGarland HaneyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Philosophy of Rene DescartesDocument8 pagesThe Philosophy of Rene DescartesSaher Sebay100% (1)

- A. J. Ayer - The Elimination of MetaphysicsDocument1 pageA. J. Ayer - The Elimination of MetaphysicsSyed Zafar ImamPas encore d'évaluation

- Aristotle: Father of Logic and Scientific MethodDocument16 pagesAristotle: Father of Logic and Scientific MethodFarooq RahPas encore d'évaluation

- Laws of NatureDocument4 pagesLaws of NatureLo WeinPas encore d'évaluation

- ADJEI v. FORIWAADocument7 pagesADJEI v. FORIWAANaa Odoley Oddoye100% (1)

- Really Distinguishing Essence From EsseDocument55 pagesReally Distinguishing Essence From Essetinman2009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Possible World SemanticsDocument3 pagesPossible World SemanticsTiffany DavisPas encore d'évaluation

- Logical FallaciesDocument28 pagesLogical FallaciesTrisha Anne Aica RiveraPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is The Value of LifeDocument3 pagesWhat Is The Value of LifeJoi PreconesPas encore d'évaluation

- Empiricism - The Origin of Knowledge Through ExperienceDocument23 pagesEmpiricism - The Origin of Knowledge Through ExperienceFil IlaganPas encore d'évaluation

- On The Euthyphro DIlemmaDocument2 pagesOn The Euthyphro DIlemmaCharles St PierrePas encore d'évaluation

- Meta EthicsDocument11 pagesMeta EthicsiscaPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes On Introduction To LogicDocument1 pageNotes On Introduction To LogicFrancisJosefTomotorgoGoingo100% (1)

- Theories and Strategies of Good Decision Making PDFDocument4 pagesTheories and Strategies of Good Decision Making PDFAbera MulugetaPas encore d'évaluation

- Child Labour AssignmentDocument6 pagesChild Labour AssignmentYazhlini TholgappianPas encore d'évaluation

- Descartes 1 - The Method of DoubtDocument4 pagesDescartes 1 - The Method of Doubtaexb123Pas encore d'évaluation

- Deontological EthicsDocument8 pagesDeontological EthicsDarwin Agustin LomibaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Logic 1 BriefDocument30 pagesLogic 1 BriefPratima KamblePas encore d'évaluation

- Discussion 2 The Philosophical SelfDocument23 pagesDiscussion 2 The Philosophical SelfEthan Manuel Del VallePas encore d'évaluation

- Reflecting On Descarte MeditationsDocument12 pagesReflecting On Descarte MeditationsSeanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Embodied SubjectDocument44 pagesThe Embodied SubjectChris Jean OrbitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Plato's Doctrine of Forms ExplainedDocument9 pagesPlato's Doctrine of Forms ExplainedpreformanPas encore d'évaluation

- Plato's Theory of FormsDocument2 pagesPlato's Theory of FormsSkyler Lee100% (1)

- Descartes Meditations Notes SummaryDocument8 pagesDescartes Meditations Notes SummaryNavid JMPas encore d'évaluation

- 17th & 18th Century Philosophy Exam 1 Study GuideDocument7 pages17th & 18th Century Philosophy Exam 1 Study GuidecailincounihanPas encore d'évaluation

- Descartes Meditations OutlineDocument6 pagesDescartes Meditations OutlineJae AkiPas encore d'évaluation

- Midterm 1Document6 pagesMidterm 1JACK TPas encore d'évaluation

- Attari and Raza (2012)Document15 pagesAttari and Raza (2012)Trung TungPas encore d'évaluation

- Barine (2012)Document23 pagesBarine (2012)Trung TungPas encore d'évaluation

- 327 Group 6 PresentationDocument13 pages327 Group 6 PresentationluzanelPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Analytics For Supply Chaina Dynamic-Capabilities FrameworkDocument18 pagesBusiness Analytics For Supply Chaina Dynamic-Capabilities FrameworkTrung TungPas encore d'évaluation

- Bhattacharya (2013)Document22 pagesBhattacharya (2013)Trung TungPas encore d'évaluation

- Panel Data Analysis: Fixed & Random Effects (Using Stata 10.x)Document40 pagesPanel Data Analysis: Fixed & Random Effects (Using Stata 10.x)CESAR MO0% (1)

- Impact of Concentrated Ownership On Firm Performance (Evidence From Karachi Stock Exchange)Document10 pagesImpact of Concentrated Ownership On Firm Performance (Evidence From Karachi Stock Exchange)Trung TungPas encore d'évaluation

- 03app - 2012 Financial Performance of SMEs Impact of Ownership Structure and Board CompositionDocument21 pages03app - 2012 Financial Performance of SMEs Impact of Ownership Structure and Board CompositionTrung TungPas encore d'évaluation

- Relationships Between Inventory, Sales and Service in A Retail Chain Store OperationDocument13 pagesRelationships Between Inventory, Sales and Service in A Retail Chain Store OperationTrung TungPas encore d'évaluation

- 01app - 2012 Board Characteristics and The Financial Performance of Nigerian Quoted FirmsDocument19 pages01app - 2012 Board Characteristics and The Financial Performance of Nigerian Quoted FirmsTrung TungPas encore d'évaluation

- Morality and Ethic DifferenceDocument3 pagesMorality and Ethic Differenceঅদ্ভুত ছেলেPas encore d'évaluation

- Wing-Cheuk Chan - Mou Zongsan's Transformation of Kant's PhilosophyDocument15 pagesWing-Cheuk Chan - Mou Zongsan's Transformation of Kant's PhilosophyAni LupascuPas encore d'évaluation

- Tales of The Mighty Dead - R Brandom - Harvard UP - 2002Document221 pagesTales of The Mighty Dead - R Brandom - Harvard UP - 2002Guada NoiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Course Name (Course Code)Document9 pagesCourse Name (Course Code)Norhafiza RoslanPas encore d'évaluation

- Russell, Bertrand - Am I An Atheist or An Agnostic PDFDocument5 pagesRussell, Bertrand - Am I An Atheist or An Agnostic PDFToño JVPas encore d'évaluation

- Avicenna and The Resurrection of The BodyDocument410 pagesAvicenna and The Resurrection of The BodyRasoul.NamaziPas encore d'évaluation

- Logical AnalysisDocument28 pagesLogical AnalysisVirginia FernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Wishful ThinkingDocument2 pagesWishful Thinkingjamie_xiPas encore d'évaluation

- Is Revelation Necessary in The Modern and Post-Modern Times?Document27 pagesIs Revelation Necessary in The Modern and Post-Modern Times?Dominic M NjugunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Atomic Theory in Indian PhilosophyDocument5 pagesAtomic Theory in Indian PhilosophyShyam MishraPas encore d'évaluation

- Phenomenology and ReligionDocument340 pagesPhenomenology and Religionmatteosettura100% (5)

- Peternson Michael. L. - God and EvilDocument145 pagesPeternson Michael. L. - God and EvilAlisson MauriloPas encore d'évaluation

- 1982 LandauDocument7 pages1982 LandaucentralparkersPas encore d'évaluation

- Exploring Free Will and DeterminismDocument4 pagesExploring Free Will and DeterminismアダムPas encore d'évaluation

- Eng 102 Appendix FallaciesDocument23 pagesEng 102 Appendix FallaciesjeanninestankoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Real You Doesnt Have CancerDocument3 pagesThe Real You Doesnt Have CancerjubeshPas encore d'évaluation

- Relativism in Contemporary American Philosophy - Continuum Studies in American PhilosophyDocument201 pagesRelativism in Contemporary American Philosophy - Continuum Studies in American PhilosophyIury Florindo100% (1)

- Rational Action - Carl HempelDocument20 pagesRational Action - Carl HempelMarcelaPas encore d'évaluation

- David Hume - Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779)Document276 pagesDavid Hume - Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779)WaterwindPas encore d'évaluation

- Analytic PhilosophyDocument8 pagesAnalytic PhilosophyJerald M JimenezPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophical FoundationsDocument14 pagesPhilosophical FoundationsMyla Capellan OgayaPas encore d'évaluation

- PHILOSOPHY and Its Conflict With ISLAMDocument4 pagesPHILOSOPHY and Its Conflict With ISLAMIbn SadiqPas encore d'évaluation

- Standpoint Theory PDFDocument26 pagesStandpoint Theory PDFEwerton M. LunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Phil 102 Personal Identity HumeDocument32 pagesPhil 102 Personal Identity Humerhye999Pas encore d'évaluation

- Consciousness, Function, and Representation: Collected PapersDocument5 pagesConsciousness, Function, and Representation: Collected PapersDiego Wendell da SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical analysis of Hindu beliefs in an afterlifeDocument1 pageCritical analysis of Hindu beliefs in an afterlifeJackieCressPas encore d'évaluation

- Scandinavian Realist V American RealistDocument13 pagesScandinavian Realist V American RealistSudhakarMishraPas encore d'évaluation

- Immanance Self Experience and TranscendenceDocument28 pagesImmanance Self Experience and Transcendencewww.alhassanain.org.english100% (1)

- Is There Intuitive Knowledge. Moritz SchlickDocument9 pagesIs There Intuitive Knowledge. Moritz Schlickxtra_ostPas encore d'évaluation

- Medieval Philosophy Essential Readings With Commentary KlimaDocument402 pagesMedieval Philosophy Essential Readings With Commentary KlimaLiliana Mg100% (2)