Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

2568 8998 1 PB

Transféré par

tracker1234Description originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

2568 8998 1 PB

Transféré par

tracker1234Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Editorial

Community Psychiatry in a Sri Lankan setting: Should we rush to push the boundaries?

Rajiv Weerasundera

Summary

Sri Lanka is preparing to introduce new mental health laws incorporating aspects of community care amidst global acceptance of Community Psychiatry as the ideal model of service delivery in mental health. However, this model needs to be reviewed not only because of the high financial and human resources

it requires but also in light of recent reports that it has not yielded expected results in some developing countries. A more practical framework, incorporating the many specific factors of the milieu in which it operates, is advocated especially for a country such as Sri Lanka with its distinctive advantages and limitations. SL J Psychiatry 2010; 1 (2):27-28

The parameters of service delivery in mental health are subject to constant review and change. This is more so in the current Sri Lankan setting as the country gears itself to provide care under a new Mental Health Act. In this context, there appears to be a consensus that there is a need for Community Psychiatry, indicating a preference for a shift from hospital based care (1, 2). The concept of formalized Community Psychiatry originated not because of evidence that it was a superior method of treatment but due to a social need to destigmatise the mentally ill and offer them a humane form of care(3). Since then, developed countries have stayed with, evolved and enhanced that model albeit with proportionate improvements in the infrastructure and human resources involved. With this sea-change in the method of service delivery in mental health care in the developed world, there has been a global trend to accept it as the ideal to aspire for. Even in the region, countries such as India and Pakistan have embraced it with few reservations (4). In Sri Lanka, poised as it is to implement drastic changes to archaic mental health legislation, this is an opportune moment to pause and take stock. That is not only because of the changing social milieu in a country in the midst of post-war transformation but also because of the growing concerns about ideal community based mental health care not yielding expected returns in developing countries (5). Such a model envisages certain pre-requisites: services provided on the basis of a geographical area, a comprehensive care package delivered through a multidisciplinary team and liaison with hospital services at the discretion of the team, rather than the service user (6). Obviously, such a model uses up vast resources, both in personnel and in infrastructure. Some drawbacks that could crop up in a Sri Lankan setting can be readily foreseen. There are likely to be limitations on the required infrastructure. This could lead to wide disparities in the services offered in the different regions.

Trained personnel have always been in short supply and will not be available in adequate numbers in the near future. Even more daunting will be the prospect of imposing a tightly controlled referral system on a population used to seeing a specialist as the first point of contact. How the system of a structured and formal system of care will fare in a culture that is steeped not only in an indigenous system of medicine but also in a belief system that heavily incorporates the supernatural into mental health problems is also a pertinent issue. Given these concerns, it is proposed that the Sri Lankas particular attributes be taken into consideration in developing a satisfactory model of mental health care: a geographically small country which makes most areas accessible to regional centres, a free health service, an established and efficient primary care network, a literate population and a communication network that appears to be growing exponentially. If all these factors are taken due advantage of, it could still be possible to provide reasonable mental health care to the majority, if not the entire population but it is a task that must be undertaken judiciously, with much planning and with careful attention to detail. A key issue in this exercise would be in identifying the primary service provider of psychiatric services. The use of the term psychiatric services, rather than mental health service is deliberate; it is suggested that given the frailties of the Sri Lankan health care system which makes it vulnerable for exploitation by many, the psychiatric service provider would play a pivotal role in the success (or failure!) of any mental health care model. At present, such services are provided by a network of a few dozen psychiatrists, about one hundred diplomates trained in the specialty for one year and a few hundred medical officers who are unfortunately not positioned in a manner that suggests an equitable distribution of human resources (7).

Sri Lanka Journal of Psychiatry Vol 1(2) Dec 2010

27

Weerasundera A more co-ordinated, rather than ad-hoc, placement of these scarce human resources is undoubtedly called for. At least at the trained medical officer level, it is suggested that they should also utilise the existing health care infrastructure as much as it is feasible. By so doing, they may not be locating themselves in a specially designated mental health facility, but they would still be in the community which would arguably be more acceptable to those sections of the population who are wary of seeking mental health care. A comment is also relevant on the recent clamour for community psychiatrists. This is indeed a concept to strive for in a country which boasts of a lesser number of specialists in Psychiatry than in most other specialties, but that does not make a case to abdicate that role to others, when, the world over, this is a position served primarily by psychiatrists. A more practical model-at least in the short term-would be for psychiatrists to divide their time between their hospitals and the communities that those facilities serve. Certainly, the provision of specialists in other sub-specialties such as Forensic Psychiatry and Child Psychiatry must take precedence. In the recent past there has been a growing body of evidence accumulating against the strategy of importing the Community Psychiatry model as it is practiced in developed countries and implanting it in less affluent nations (8). With the benefit of such hindsight, it should be possible to devise a model of care although evidence based medicine and randomized controlled trials may not reveal what that model is. It needs to be a system that not only incorporates the benefits of a community care system but is also able to seamlessly integrate into the specific social, cultural and health needs of a given society, taking into account especially the limitations that it is likely to encounter. Such a structure may not constitute Community Psychiatry as many know it. It may not even be located in the community. Instead, it would be a model of mental health care that serves the community that it operates in. That could be the new paradigm for Community Psychiatry for developing nations.

Declaration of interest

None

Rajiv Weerasundera, MBBS, MD(Psych), Senior Lecturer, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Sri Jayawardenepura, Sri Lanka E mail: rajivweerasundera@yahoo.com

References

1. 2. Tyrer P. Cost-effective or profligate community psychiatry? Br J Psychiatry 1998; 172: 1-3. Health.gov.lk[home page on the internet].Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka. Available at: http://www.health. gov.lk/mental_health_act.html (Accessed November 2010) Farooq S, Minhas FA. Community psychiatry in developing countries-a misnomer? The Psychiatrist 2001; 25: 226-7. Goldberg, D. Psychiatry and primary care. World Psychiatry 2003; 2(3): 153157. Jacob KS. Community care for people with mental disorders in developing countries. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178: 296-298. Brown DB, Goldman CR, Thompson KS, Cutler DL. Training residents for community psychiatric practice: guidelines for curriculum development. Community Mental Health J 1993; 3: 271-283. De Silva V, Hanwella R. Mental health in Sri Lanka. The Lancet 2010; 376: 88-9. Law SF. Are western community psychiatric models suitable for China? An examination of cultural and socio-economic foundations of western community psychiatry models using assertive community treatment as an example. International J of Culture and Mental Health 2008; 1: 134-154.

3. 4. 5. 6.

7. 8.

28

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- 2016 Anger Management FlyerDocument1 page2016 Anger Management Flyertracker1234Pas encore d'évaluation

- Medical Ordinance IN SRILANKADocument27 pagesMedical Ordinance IN SRILANKAtracker1234Pas encore d'évaluation

- Psychological Disturbances in Obstetrics: (Part I)Document3 pagesPsychological Disturbances in Obstetrics: (Part I)tracker1234Pas encore d'évaluation

- Councelling-Mental HealthDocument3 pagesCouncelling-Mental Healthtracker1234Pas encore d'évaluation

- Whithier Mankind - EditedDocument7 pagesWhithier Mankind - Editedtracker1234Pas encore d'évaluation

- Do Rituals Violate The Rights of The Mentally Ill Patient?: G.S.S.R. Dias & Induwara GooneratneDocument3 pagesDo Rituals Violate The Rights of The Mentally Ill Patient?: G.S.S.R. Dias & Induwara Gooneratnetracker1234Pas encore d'évaluation

- Finallist 2012Document147 pagesFinallist 2012tracker1234Pas encore d'évaluation

- 06 2006 (E)Document34 pages06 2006 (E)tracker1234100% (2)

- Kesel WagawaDocument4 pagesKesel WagawaRavindra Kumara75% (8)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Public International Law Green Notes 2015Document34 pagesPublic International Law Green Notes 2015KrisLarr100% (1)

- ESU Mauritius Newsletter Dec 2014Document8 pagesESU Mauritius Newsletter Dec 2014Ashesh RamjeeawonPas encore d'évaluation

- Pentecostal HealingDocument28 pagesPentecostal Healinggodlvr100% (1)

- My ResumeDocument2 pagesMy ResumeWan NaqimPas encore d'évaluation

- Producto Académico #2: Inglés Profesional 2Document2 pagesProducto Académico #2: Inglés Profesional 2fredy carpioPas encore d'évaluation

- Great Is Thy Faithfulness - Gibc Orch - 06 - Horn (F)Document2 pagesGreat Is Thy Faithfulness - Gibc Orch - 06 - Horn (F)Luth ClariñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing PlanDocument41 pagesMarketing PlanMark AbainzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Writing - Hidden Curriculum v2 EditedDocument6 pagesWriting - Hidden Curriculum v2 EditedwhighfilPas encore d'évaluation

- Lite Touch. Completo PDFDocument206 pagesLite Touch. Completo PDFkerlystefaniaPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Export: 1) Establishing An OrganisationDocument5 pagesHow To Export: 1) Establishing An Organisationarpit85Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sino-Japanese Haikai PDFDocument240 pagesSino-Japanese Haikai PDFAlina Diana BratosinPas encore d'évaluation

- Long 1988Document4 pagesLong 1988Ovirus OviPas encore d'évaluation

- RubricsDocument1 pageRubricsBeaMaeAntoniPas encore d'évaluation

- Is 13779 1999 PDFDocument46 pagesIs 13779 1999 PDFchandranmuthuswamyPas encore d'évaluation

- IBM System X UPS Guide v1.4.0Document71 pagesIBM System X UPS Guide v1.4.0Phil JonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Calendar of Cases (May 3, 2018)Document4 pagesCalendar of Cases (May 3, 2018)Roy BacaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Bfhi Poster A2Document1 pageBfhi Poster A2api-423864945Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Preparedness of The Data Center College of The Philippines To The Flexible Learning Amidst Covid-19 PandemicDocument16 pagesThe Preparedness of The Data Center College of The Philippines To The Flexible Learning Amidst Covid-19 PandemicInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyPas encore d'évaluation

- In Mein KampfDocument3 pagesIn Mein KampfAnonymous t5XUqBPas encore d'évaluation

- Sodium Borate: What Is Boron?Document2 pagesSodium Borate: What Is Boron?Gary WhitePas encore d'évaluation

- Star QuizDocument3 pagesStar Quizapi-254428474Pas encore d'évaluation

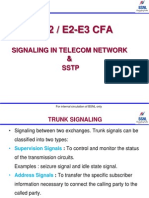

- Signalling in Telecom Network &SSTPDocument39 pagesSignalling in Telecom Network &SSTPDilan TuderPas encore d'évaluation

- Dispersion Compensation FibreDocument16 pagesDispersion Compensation FibreGyana Ranjan MatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Hercules Industries Inc. v. Secretary of Labor (1992)Document1 pageHercules Industries Inc. v. Secretary of Labor (1992)Vianca MiguelPas encore d'évaluation

- Large Span Structure: MMBC-VDocument20 pagesLarge Span Structure: MMBC-VASHFAQPas encore d'évaluation

- Re CrystallizationDocument25 pagesRe CrystallizationMarol CerdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Insomnii, Hipersomnii, ParasomniiDocument26 pagesInsomnii, Hipersomnii, ParasomniiSorina TatuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Mahatma Gandhi in The Freedom Movement of IndiaDocument11 pagesThe Role of Mahatma Gandhi in The Freedom Movement of IndiaSwathi Prasad100% (6)

- Lista Verbelor Regulate - EnglezaDocument5 pagesLista Verbelor Regulate - Englezaflopalan100% (1)

- Anindya Anticipatory BailDocument9 pagesAnindya Anticipatory BailYedlaPas encore d'évaluation