Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Building A Research Agenda For Indigenous Epistemologies and Education

Transféré par

Charlie EstevezDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Building A Research Agenda For Indigenous Epistemologies and Education

Transféré par

Charlie EstevezDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Building a Research Agenda for Indigenous Epistemologies and Education

LINDA TUHIWAI S MITH University of Auckland One emergent issue in relation to research on Indigenous epistemologies and education concerns the extent to which Indigenous epistemologies lead to new kinds of educational experiences and outcomes and pose new research questions. This commentary responds to the sense of limits and possibilities for Indigenous education that are raised by the research in this theme issue, and suggests that there are indeed new questions to be asked and answered through research. [Indigenous education, Indigenous epistemologies, Indigenous schooling, research on Indigenous peoples] As an Indigenous researcher in education, what interests me most about this theme issue is that each paper in some way addresses educational concerns that are shared in Indigenous contexts around the world. Each of the ve feature articles raises interesting questions about the possibilities and the limits of Indigenous epistemologies, Indigenous language, Indigenous communities and Indigenous educators, researchers, and resource people to inform educational and schooling systems and practices. The articles address these questions through research that examines alternative systems and conceptions of education that draw entirely on Indigenous epistemologies, public school attempts to teach culture, tribally based schooling, and language- and culture-based education. As someone who has been involved in system-wide educational reform, the development of alternative educational options from early childhood to higher education, and the development of Indigenous initiatives in the mainstream system, it excites me to see the range of research being conducted by Indigenous educational researchers. It is important to build the evidence on Indigenous education for reasons that are both educational and political. In her recent essay in Educational Researcher, Norma Gonz lez (2004) reminds us a that the anthropology of education has been concerned with more than what occurs in formal schooling systems, as anthropology privileges and seeks to understand the wider dynamics of cultural systems in which learning, teaching, socialization, and cultural transformation occur. The study of education in other cultures and the study of other cultures in education seem to be very separate areas of educational research, with the former approach seeking descriptions of worldviews, cultural patterns of socialization, and development in non-Western cultures and societies, and the latter approach more concerned with issues of diversity, pluralism, and multiculturalism in Western societies. In Gonz lez analysis, these two approaches a address in some way anthropological concerns about cultural continuity or discontinuity. The feature articles in this theme issue do not t easily into the study of education in other cultures or the study of other cultures in education. Although these articles grapple with a range of educational issues that confront Indigenous communities, documenting different responses and solutions to those issues, they seem to collapse or speak back to the ways in which the cultures of the other and formal or informal systems of education have been studied. The speaking back is achieved in these articles with a certain amount of practical ease: The signicance of the questions each author addresses draws from the very practical problems that have

Anthropology and Education Quarterly, Vol. 36, Issue 1, pp. 9395, ISSN 0161-7761, electronic ISSN 15481492. C 2005 by the American Anthropological Association. All rights reserved. Please direct all requests for permission to photocopy or reproduce article content through the University of California Presss Rights and Permissions website, at http://www.ucpress.edu/journals/rights.htm.

93

94

Anthropology & Education Quarterly

Volume 36, 2005

been identied by Indigenous communities and researchers rather than from traditional disciplinary concerns; the writers eschew decit or deprivation views of culture and are fully aware of the colonial histories of schooling for Indigenous communities; the essays give voice to Indigenous knowledge, culture, and community in multiple ways without romanticizing the issues, cultures, or educational responses. The research presented in these articles illustrates different attempts to make education and schooling systemswhether at structural, curricular, or pedagogical levelswork better for students and teachers, and for communities and their cultural worldviews, practices, and contemporary realities. There are some emergent theoretical issues that arise from a reading of these articles and indeed from other writings in the area of Indigenous knowledge, culture, and education. From a mainstream educational perspective and from any survey of educational research that concerns Indigenous and ethnic minorities, the overwhelming educational concern is underachievement in public schooling systems. The problem of educational underachievement has been studied from different disciplinary and theoretical perspectives and seems now to be more frequently dened as being about the quality of teaching and learning. Questions of Indigenous knowledge, language, and culture have usually been viewed as potential solutions to make classrooms, the curricula, and teachers more responsive and inclusive, with the students more engaged in schooling and therefore more likely to achieve. Although the research generally asks deep questions of structure, of systems and policies, an underlying assumption of much research is that schooling is inherently good for Indigenous children and their communities and the greater challenge is about how to get the best match, how to make it work betterhow to t students, parents, the curriculum, and teacher practices into a system that will work for all. Indigenous communities often have a quite different set of questions that frames the key educational issue as being primarily about epistemic self-determination that includes language and culture and the challenges of generating schooling approaches from a different epistemological basis. These are at least two quite different ways to think about Indigenous education and the agenda for educational research. In my view, both approaches and indeed other approaches need to be conducted simultaneously because we are not dealing with a unitary, simple, or static set of conditions. There are, however, major gaps in the research that explores the interface of Indigenous epistemology and education and schooling for the 21st century. Reconceptualizing education from an Indigenous perspective is innovative and presents a great opportunity to consider a wide range of educational issues from a different basis. In the same way that challenges about the relationships between schooling and the economy have been dealt with, as well as the de-schooling of society, or the potential of liberatory pedagogies to make a difference for learners in classrooms, Indigenous frameworks for thinking about schooling present new and different ways to think through the purpose, practices, and outcomes of schooling systems. In the case of New Zealands alternative Maori language schools, known as Kura Kaupapa Maori, the evidence of their efforts is only just now appearing in major studies such as the National Educational Monitoring Project (NEMP), funded by the Ministry of Education. One major problem with such studies is that minorities become almost invisible in the research and much of the assessment is conducted in the dominant language rather than the language of the children or the schools medium of instruction. The NEMP has attempted to address both issues through inclusion of a specially constituted sample of students from Kura Kaupapa Maori and with researchers and interviews that can be conducted in the Maori language. The evidence to date continues to highlight major achievement disparities between Maori, Pacic Islands students, and the dominant population group; however, it also raises interesting differencesfor example, between the attitudes of Maori children in conventional mainstream schools who may also be in bilingual classrooms and Maori children who attend the Kura Kaupapa Maori. Kura Kaupapa Maori began in the mid-1980s with a very explicit vision of building a schooling option grounded in Maori philosophies and taught through Maori

Smith

Indigenous Education and Epistemologies

95

language immersion. Kura Kaupapa Maori have always resisted labels that described them as simply Maori-language schools or bilingual schools because the philosophy was integral to the conception of education. As one example of a difference that has emerged in the NEMP (NEMP 2004), Maori children in Kura Kaupapa Maori are said to have more positive attitudes toward some curriculum subjects than Maori children in the mainstream schools. We can dismiss this nding as too little too soon, or we could ponder over the difference and think about how to explore it further. Certainly in Indigenous education having students engaged in the curriculum and expressing positive attitudes is a small triumph against the grim picture of educational disengagement. The difference from my perspective hints at a possibility, slight as it may be, that Indigenous epistemologies rather than, say, pedagogical styles, can lead to a different schooling experience and produce a different kind of learner. Possibilities such as this open up new vistas in educational research that relate to Indigenous epistemologies and schooling, but we have to recognize them amidst the usual concerns raised by educational research and evaluation. New epistemologies that inform schooling will produce new questions and raise new challenges for research. The educational initiatives in the research presented in this issue raise many important questions to ponder and think through in relation to a broader agenda of Indigenous educational research. It is extremely important to build rich ethnographic accounts of Indigenous education because these accounts document innovative solutions, telling the stories of Indigenous engagement with education and highlighting issues to be debated or further researched. This theme issue in its entirety provides a valuable resource for educators who work in Indigenous education, and for all concerned with educational equity and justice.

Linda Tuhiwai Smith is professor and joint director of Nga Pae o te Maramatanga (Horizons of Insight), National Institute of Research Excellence in Maori Development and Advancement, University of Auckland (lt.smith@auckland.ac.nz).

References Cited

National Educational Monitoring Project (NEMP) 2004 Electronic document, www.nemp.otago.ac.nz, accessed November 30. Gonz lez, Norma a 2004 Disciplining the Discipline: Anthropology and the Pursuit of Quality Education. Educational Researcher (33)5:1725.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Black Socio-Cultural Cognitive Learning Style HandbookD'EverandThe Black Socio-Cultural Cognitive Learning Style HandbookPas encore d'évaluation

- Pendekatan Pengajaran MCE-tulis IniDocument19 pagesPendekatan Pengajaran MCE-tulis Initalibupsi1Pas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Culturally Responsive TeachingDocument10 pagesWhat Is Culturally Responsive TeachingKaviyasan Udayakumar100% (1)

- Making Connections To The Past and PresentDocument37 pagesMaking Connections To The Past and Presentapi-496629376Pas encore d'évaluation

- Biculturalism in New Zealand Secondary Schools Carolyn StirlingDocument10 pagesBiculturalism in New Zealand Secondary Schools Carolyn StirlingKhemHuangPas encore d'évaluation

- Examples of Current Issues in The Multicultural ClassroomDocument5 pagesExamples of Current Issues in The Multicultural ClassroomFardani ArfianPas encore d'évaluation

- Annotated BibliographyDocument13 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-295669671Pas encore d'évaluation

- CBE Relationship To Student OutcomesDocument30 pagesCBE Relationship To Student OutcomesEde SzaboPas encore d'évaluation

- Identity Community and Diversity Retheorizing Multicultural Curriculum For The Postmodern EraDocument13 pagesIdentity Community and Diversity Retheorizing Multicultural Curriculum For The Postmodern EraDiana VillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal 13 PDFDocument14 pagesJurnal 13 PDFMuhammad BasoriPas encore d'évaluation

- Under Construction The Development of Mu PDFDocument22 pagesUnder Construction The Development of Mu PDFlancelotdellagoPas encore d'évaluation

- Diversity, Multiculturalism, Gender, and Exceptionality in The SocStud ClassroomDocument43 pagesDiversity, Multiculturalism, Gender, and Exceptionality in The SocStud ClassroomJazel May PontePas encore d'évaluation

- Culturally Relevant Teaching in ApplicationDocument13 pagesCulturally Relevant Teaching in Applicationyankumi07100% (1)

- Funds of Knowledge and Discourses and Hybrid SpaceDocument10 pagesFunds of Knowledge and Discourses and Hybrid SpaceCris Leona100% (1)

- Chapter 1-3 - RangelDocument17 pagesChapter 1-3 - Rangelraisy jane senocPas encore d'évaluation

- Culturally Responsive Final PaperDocument7 pagesCulturally Responsive Final Paperirenealarcon7Pas encore d'évaluation

- Diversity BriefDocument16 pagesDiversity Briefapi-253748903Pas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper Topics For Multicultural EducationDocument4 pagesResearch Paper Topics For Multicultural EducationyquyxsundPas encore d'évaluation

- A2 Research On Culture-Cultural DiversityDocument2 pagesA2 Research On Culture-Cultural DiversityNorielyn RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Norton and Toohey (2004) Critical - Pedagogies - and - Language - Learning 2004Document10 pagesNorton and Toohey (2004) Critical - Pedagogies - and - Language - Learning 2004Verenice ZCPas encore d'évaluation

- Hall 2005 Cha5Document19 pagesHall 2005 Cha5Shawn Lee BryanPas encore d'évaluation

- Pedagogical Conditions For The Formation of Gender Equality Thinking in StudentsDocument4 pagesPedagogical Conditions For The Formation of Gender Equality Thinking in StudentsAcademic JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- A Reflection On 5 Dimensions of Multicultural EducationDocument6 pagesA Reflection On 5 Dimensions of Multicultural EducationNicole Damian BorromeoPas encore d'évaluation

- rtl2 Assignment 2 19025777Document14 pagesrtl2 Assignment 2 19025777api-431932152Pas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching To and Through Cutural Diversity PDFDocument23 pagesTeaching To and Through Cutural Diversity PDFYarella EspinozaPas encore d'évaluation

- CultureDocument20 pagesCultureSsewa AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Deconstructing Power Privilege and SilenDocument18 pagesDeconstructing Power Privilege and SilenPj InudomPas encore d'évaluation

- Exploring Nature of Criticality in High School Science Teaching: Sociopolitical Consciousness in Multicultural Science EducationDocument13 pagesExploring Nature of Criticality in High School Science Teaching: Sociopolitical Consciousness in Multicultural Science EducationYULY ALEJANDRA ACUÑA LARAPas encore d'évaluation

- Kyla Mccartney Final PaperDocument31 pagesKyla Mccartney Final Paperapi-487885607Pas encore d'évaluation

- Multicultural EducationDocument11 pagesMulticultural EducationGrace PatunobPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Values Taught in ClassroomsDocument4 pagesHidden Values Taught in ClassroomsMike McDPas encore d'évaluation

- Article ReadingDocument7 pagesArticle Readingapi-289249800Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ethnic Studies With K - 12 Students, Families, and Communities: The Role of Teacher Education in Preparing Educators To Serve The PeopleDocument15 pagesEthnic Studies With K - 12 Students, Families, and Communities: The Role of Teacher Education in Preparing Educators To Serve The PeopleMaria SantanaPas encore d'évaluation

- My Strategy PlanDocument8 pagesMy Strategy PlanPrincess Marquez TayongtongPas encore d'évaluation

- Overcoming Challenges in Multicultural ClassroomsDocument12 pagesOvercoming Challenges in Multicultural ClassroomsMuhammad HilmiPas encore d'évaluation

- Sowden, C - Culture and The Good TeacherDocument7 pagesSowden, C - Culture and The Good Teacherhellojobpagoda100% (3)

- Multicultural Education Refers To Any Form of Education or Teaching That IncorporatesDocument5 pagesMulticultural Education Refers To Any Form of Education or Teaching That IncorporatesurlPas encore d'évaluation

- tarman_ilknur_bulentDocument21 pagestarman_ilknur_bulentbadreddine-tabbiPas encore d'évaluation

- 2classroom Culture - Understanding Language - University of SouthamptonDocument4 pages2classroom Culture - Understanding Language - University of SouthamptonBlooming TreePas encore d'évaluation

- Culture and LearningDocument5 pagesCulture and LearningCalvi JamesPas encore d'évaluation

- Williams 606 Reflection PointDocument5 pagesWilliams 606 Reflection Pointapi-357266639Pas encore d'évaluation

- Escasinas Rhegee Educ 101 Midterm Exam 2021Document6 pagesEscasinas Rhegee Educ 101 Midterm Exam 2021Rhegee EscasinasPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper Multicultural EducationDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Multicultural Educationiiaxjkwgf100% (1)

- Romberg (2004), DefinesDocument7 pagesRomberg (2004), DefinesWashington NyamandePas encore d'évaluation

- Aboriginal Education - Assessment 1Document6 pagesAboriginal Education - Assessment 1Rayanne HamzePas encore d'évaluation

- Teacher Education For Inclusion International Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesTeacher Education For Inclusion International Literature ReviewwoeatlrifPas encore d'évaluation

- Addressing Literacy Needs in Culturally and LinguisticallyDocument28 pagesAddressing Literacy Needs in Culturally and LinguisticallyPerry Arcilla SerapioPas encore d'évaluation

- Concept NoteDocument3 pagesConcept NoteYatin BehlPas encore d'évaluation

- Making A Case For A Multicultural Approach For Learning 412 1Document8 pagesMaking A Case For A Multicultural Approach For Learning 412 1api-384483769Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Dimensions of Multicultural EducationDocument6 pagesThe Dimensions of Multicultural EducationERWIN MORGIAPas encore d'évaluation

- 155-Article Text-153-1-10-20100319Document14 pages155-Article Text-153-1-10-20100319Choko G.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Melting Pot Influences On Secondary English CurricDocument12 pagesMelting Pot Influences On Secondary English CurricrewgwrgwPas encore d'évaluation

- LS III Midterm 1stDocument11 pagesLS III Midterm 1stJohn Nathan FranciscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Chartock's Strategies and Lessons For Culturally Responsive TeachingDocument8 pagesReview of Chartock's Strategies and Lessons For Culturally Responsive TeachingEric WellsPas encore d'évaluation

- Multicultural Education in Malaysian Perspective: Instruction and Assessment Sharifah Norsana Syed Abdullah, Mohamed Najib Abdul Ghaffar, PHD, P - Najib@Utm - My University Technology of MalaysiaDocument10 pagesMulticultural Education in Malaysian Perspective: Instruction and Assessment Sharifah Norsana Syed Abdullah, Mohamed Najib Abdul Ghaffar, PHD, P - Najib@Utm - My University Technology of Malaysiakitai123Pas encore d'évaluation

- CLR Book Report Assignment 5600 PDFDocument6 pagesCLR Book Report Assignment 5600 PDFRedemptah Mutheu Mutua50% (2)

- Multiculturalism Project 2Document10 pagesMulticulturalism Project 2api-247283121Pas encore d'évaluation

- Contoh Kajian EtnografiDocument32 pagesContoh Kajian EtnografiNayo SafwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Term Paper Multicultural EducationDocument6 pagesTerm Paper Multicultural Educationafdtebpyg100% (1)

- Does Multicultural Education Really Benefit Various CulturesDocument16 pagesDoes Multicultural Education Really Benefit Various CulturesYek Yee LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Media Influence & Potential SolutionsDocument5 pagesMedia Influence & Potential SolutionsHìnhxămNơigóckhuấtTimAnhPas encore d'évaluation

- Frame CorrectionDocument32 pagesFrame CorrectionsahayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Division of Las Pinas Golden Acres National High School: I. ObjectivesDocument2 pagesDivision of Las Pinas Golden Acres National High School: I. ObjectivesARVEE DAVE GIPA100% (1)

- Science-Dll-Week-6-Quarter 1Document7 pagesScience-Dll-Week-6-Quarter 1Ma. Joan Mae MagnoPas encore d'évaluation

- AI-Enhanced MIS ProjectDocument96 pagesAI-Enhanced MIS ProjectRomali Keerthisinghe100% (1)

- A Feasibility Study On Establishing A Dance Studio "EmotionDocument12 pagesA Feasibility Study On Establishing A Dance Studio "EmotionJenny GalayPas encore d'évaluation

- Of Studies (Analysis)Document3 pagesOf Studies (Analysis)Ble Sea Nah0% (1)

- CII Recognition: of Prior LearningDocument3 pagesCII Recognition: of Prior LearningShanmuganathan RamanathanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Line Manager in Managing PerformanceDocument20 pagesThe Role of Line Manager in Managing PerformanceOrbind B. Shaikat100% (2)

- Frei Universitat PDFDocument167 pagesFrei Universitat PDFalnaturamilkaPas encore d'évaluation

- Resume of MD - Rayhanur Rahman Khan: ObjectiveDocument3 pagesResume of MD - Rayhanur Rahman Khan: ObjectiveRayhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Principles of Curriculum DevelopmentDocument19 pagesPrinciples of Curriculum DevelopmentMichelleManguaMironPas encore d'évaluation

- Cambridge English Exams Paper-Based Vs Computer-BasedDocument4 pagesCambridge English Exams Paper-Based Vs Computer-BasedjusendqPas encore d'évaluation

- NH Màn Hình 2024-03-03 Lúc 15.45.39Document1 pageNH Màn Hình 2024-03-03 Lúc 15.45.39hiutrunn1635Pas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of Peer Pressure on Academic Performance (40Document6 pagesEffects of Peer Pressure on Academic Performance (40MaynardMiranoPas encore d'évaluation

- International Programmes in Germany 2016 Public Art and New Artistic Strategies - Bauhaus-Universität Weimar - WeimarDocument7 pagesInternational Programmes in Germany 2016 Public Art and New Artistic Strategies - Bauhaus-Universität Weimar - WeimarJhon WilsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Ph.D. Enrolment Register As On 22.11.2016Document35 pagesPh.D. Enrolment Register As On 22.11.2016ragvshahPas encore d'évaluation

- E3 ESOL Reading Assessor Guidance and Markscheme PPBDocument8 pagesE3 ESOL Reading Assessor Guidance and Markscheme PPBPatrick MolloyPas encore d'évaluation

- Isph-Gs PesDocument13 pagesIsph-Gs PesJeremiash Noblesala Dela CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Holy Child Catholic School v. Hon. Patricia Sto. TomasDocument10 pagesHoly Child Catholic School v. Hon. Patricia Sto. TomasEmir MendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson-Plan-Voc Adjs Appearance Adjs PersonalityDocument2 pagesLesson-Plan-Voc Adjs Appearance Adjs PersonalityHamza MolyPas encore d'évaluation

- Mapeh 10 Week 1 Week 2Document12 pagesMapeh 10 Week 1 Week 2Christian Paul YusiPas encore d'évaluation

- Trifles DiscussionDocument11 pagesTrifles Discussionapi-242602081Pas encore d'évaluation

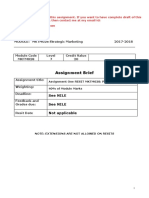

- MKTM028 2017 18 As1 MasterDocument9 pagesMKTM028 2017 18 As1 Masterprojectwork185Pas encore d'évaluation

- 002 Careers-Personality-And-Adult-Socialization-Becker-and-StraussDocument12 pages002 Careers-Personality-And-Adult-Socialization-Becker-and-StraussEmiliano EnriquePas encore d'évaluation

- Cultivating Critical Thinking SkillsDocument20 pagesCultivating Critical Thinking SkillsAdditional File StoragePas encore d'évaluation

- Drama Games For Acting ClassesDocument12 pagesDrama Games For Acting ClassesAnirban Banik75% (4)

- Researcher Development Framework RDF Planner Overview Vitae 2012Document2 pagesResearcher Development Framework RDF Planner Overview Vitae 2012Daniel GiesPas encore d'évaluation

- Reflection of Good Governance in Sustainable Development: The Bangladesh ContextDocument16 pagesReflection of Good Governance in Sustainable Development: The Bangladesh ContextSk ByPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum 2016Document594 pagesCurriculum 2016Brijesh UkeyPas encore d'évaluation