Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Macroeconomic Relationships and the Aggregate Expenditures Model

Transféré par

Md ShohagDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Macroeconomic Relationships and the Aggregate Expenditures Model

Transféré par

Md ShohagDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Chapters 9 and 10: Macroeconomic Relationships and the Aggregate Expenditures Model

Bring a copy of these outlines (notes) to highlight and draw the graphs as go thru them in class.] Note: We construct Aggregate Expenditures and the multipliers by assuming that general price level does not change. We will later relax this assumption and derive the aggregate demand curve by changing the price level and/or the interest rate. If prices are fixed, then aggregate demand determines the aggregate quantity of goods and services sold, which equals real GDP. Aggregate Expenditures = planned consumption expenditures + planned investment + planned government expenditures on goods and services + planned net exports. In the short run, all of these are assumed to be fixed, except the consumption function. So, if any of these fixed expenditures (acting as independent variables or acting as autonomous components) change, consumption changes and the changes in consumption affect output in return. We will show that using the Keynesian cross (the aggregate expenditure/aggregate income (GDP) relationship. Actual Expenditure, Planned Expenditure, and Real GDP Actual expenditure is always equals to Real GDP, but planned expenditure may not be equal to Real GDP. Why, firms (in aggregate) may end up with more inventories or with less inventories. If planned expenditures equal to real GDP, then, actual aggregate expenditure equals Real GDP and the economy is in equilibrium. Changes in autonomous changes in Investment, Government spending, taxes, imports and exports would change the economy thru the multiplier process. When an autonomous component of Aggregate Demand changes, equilibrium output will change. The change in output will be even larger than the initial change in Aggregate Demand. This result for the change in Y to be greater than the initial change in Aggregate Demand is known as the multiplier effect. The consumption and saving functions: The Consumption Function illustrates, a consumption function shows the relationship between total consumer expenditures and total disposable income, holding all other determinants of consumption constant. No other factors are considered. The consumption function also assumes the relationship between consumption and disposable income is linear. The equation for the consumption function is:

C = a + MPC (DI ),

where C is total consumption; a is autonomous consumption, MPC is the marginal propensity to consume, and DI is disposable income.

Autonomous consumption (a) is the portion of disposable income that is independent of income. In other words, when disposable income changes, autonomous consumption does not change. The value for autonomous consumption is shown on the graph where the consumption function intersects the vertical axis. Not too much should be made of this value. It is primarily a "statistical leftover." We fit the best possible line between consumption and disposable income, and the line has to cross the vertical axis somewhere. The point where it crosses the axis is the value for a. Consumption + Saving = Disposable Income. Something that is left from taxes and not spent is saved and that is not saved must have spent. So, the marginal propensity to consume (MPC), which is change in consumption duet to a fraction of change in disposable income, and the marginal propensity of save (MPS), which the change in saving brought about by a fraction of change in disposable income must sum one. That is, MPC = MPS =1. Draw the consumption and DI relationship about here.

None-income Determinants of Consumption and Saving: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Wealth Real interest rates Expectations household debt Taxation

All of the above shift the curve up or down!

Draw the Aggregate expenditure model (only C on the vertical axis and DI on the horizontal axis) about here.

Determining Investment in the Income-Expenditure Model Investment Investment is the most volatile component of GDP. It accounts for approximately 17% of GDP. Investment is determined by interest rates, business confidence, taxes, and capacity utilization. If interest rates rise, other things equal, investment falls. Why? Investment typically requires large amounts of upfront expenditures. Businesses must either borrow the resources externally or divert resources internally to the investment project. The cost of borrowing these funds is the interest rate. When interest rates are high, it is more expensive to borrow funds, so less investment is demanded. When interest rates are low, it is cheaper to borrow funds so more investment is demanded. The figure titled "Investment Demand Curve" plots the interest rate on the vertical axis and the quantity of investment on the horizontal axis. It is downward-sloping. Business Confidence (expectations) plays a large role, perhaps the most significant role, in determining investment. Investment means borrowing now to generate income flows in the future. If projections of income in the future are high, investment now seems to be worthwhile. Future projections of income are often good guesses at best. Uncertainty in future conditions makes investment risky and volatile. Sudden changes in expectations result in sudden changes in the level of investment. Taxes also impact investment. The return on investment depends on how heavily investment income is taxed (for example, the capital gains tax). Other things equal, higher taxes result in lower investment. Technological Change- innovation, the development of new products, improvements in existing products and the creation of new machinery and production process-stimulates investment Capacity Utilization is the percentage of the existing plant and equipment that is being utilized. If capacity utilization rates are low, then the existing plant has room to expand and investment in the future will be lower. Conversely, if the utilization rates are high, then a firm might have to invest immediately to accommodate future growth. In our simplified model, we assume that interest rates are already determined, and we assume that all other determinants of investment (such as business confidence) remain unchanged. Given a particular interest rate, we can determine the level of investment that will take place in the economy. For example, suppose that the interest rate is 8.0 percent, and that rate corresponds to $600 of investment. We plot the level of investment in the figure titled "Investment Level." Aggregate expenditures go on the vertical axis while the level of income or GDP (Y) goes on the

horizontal axis. The investment line is simply a horizontal line at $600. It has a slope of zero because we assume that investment does not vary with the level of income in the economy.

(Draw the Investment schedule about here)

Draw the Aggregate expenditure model: GDP = C + Ig with only C and I about here! Differentiate the economys investment schedule, Ig , which is the amount of investment forthcoming at each level of GDP and investment demand, ID in relation to interest rates.

Government Spending and Taxes Government spending, G is assumed to be autonomous. An increase in G raises consumption, then income, then consumption, them income, etc. (in this fashion) by multiple factors.

For the time being, we assume taxes being lump-sum. A lump-sum tax is a tax that is a constant amount (the tax revenue for the government is the same) at all levels of GDP. Taxes affect consumption (and hence GDP or income) in the opposite direction of government spending, G.

Draw the AE and Real GDP relationships here, beginning with consumption, and adding I, G, T,

For example, if the MPC is .80 and autonomous investment increases by $200, equilibrium output will ultimately change by $1,000, not $200! The simple output multiplier = 1/(1-MPC). Calculating the Size of the Multiplier Effect The size of the multiplier effect is given by: Change in Output = (output multiplier) x initial change in AD where the (simple) output multiplier is defined as 1/(1-MPC). For example, with an MPC of 0.80, the simple output multiplier is 1/(1-.80) = 5, so the $200 initial increase in investment ultimately increases output by 5 x $200 = $1,000. The simple output multiplier assumes that there are no proportional taxes, that all expenditures are for domestically produced goods and services, and that the price level is fixed. Derive all Simple Multipliers and show that: Income-induced consumption is the key to understanding the output multiplier! a. b. The simple spending multiplier = 1/(1-MPC). The simple investment spending multiplier = 1/(1-MPC).

c. d.

The simple tax multiplier = -MPC/(1-MPC) the simple balanced budget multiplier = 1

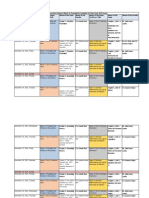

How and Why the Multiplier Works Consumption is based primarily on disposable income. According to the consumption function, C = a + b(Y-T), where "a" is a constant (the intercept of the consumption function) and b is the MPC. Thus, higher income causes higher consumption. When G rises, it increases income, then consumption, further raises consumption, which further raises income, which further raises consumption, and so on. When consumption rises, Aggregate Demand also rises. When Aggregate Demand rises, output and hence income rise. The rise in income allows people to consume more goods and services. This is called "income-induced" consumption and it raises Aggregate Demand even more. Let's work through an example. Suppose the MPC is 0.80. A University decides to build a new residence hall worth $100 million. Construction workers earn $100 million in income, and they spend 80 percent--or $80 million--dining out, going to the movies, shopping, and buying new cars. The increased spending of $80 million becomes income to the owners and employees of the restaurants, movie theatres, shopping malls, and car dealers. In turn, these people spend 80 percent of the new $80 million, or $64 million, on other goods and services. The $64 million becomes income to others in the community, and the process continues. Table 1 shows the impact of the multiplier through various rounds. When all the effects are totaled up, output will increase by $500 million because the value of the output multiplier is equal to 1/(1-.2) = 5. Remember that the initial increase in Aggregate Demand for the new residence hall was just $100 million. Initial change in Govt. exp. 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 Change in Output 100.00 80.00 64.00 51.20 40.96 32.77 26.21 20.97 16.78 67.11 500 Change in Consumption 80.00 64.00 51.20 40.96 32.77 26.21 20.97 16.78 67.11 400

Round 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 to infinity Totals

The above table can be summarized as follows and introduces you to the multiplier process. Initial change in Government purchases = G (which is equal to 100 above) First change in consumption MPC x G

Second change in consumption = MPC2 x G Third change in consumption = MPC3 x G Fourth change in consumption = MPC4 x G . . . . . . . . Y = (1 + MPC + MPC2 + MPC3 + MPC4 +..) G So that the government-purchase multiplier is Y/ G = 1 + MPC + MPC2 + MPC2 + . This expression is in the form of an infinite geometric series, and with 0 < MPC <1, it can be written as Y/ G = 1/(1-MPC)1.

The Multiplier Effect and a Permanent Change in Aggregate Demand If the government (or any other private investor) funds an on-going project like financing a school, the impact is much larger than that of a temporary increase. Suppose for simplicity that the government spends $100 to construct a new school and then spends $100 each year to operate the school. So the government is injecting $100 into the economy permanently.

Derive the AD curve by changing the price level about here (see, pp. 270-71).

1 Mathematical note: The geometric series can be proved as follows: Let z = 1 +x + x2 + . Multiply both sides of the equation by x: zx = x + x2 +x3 + . Subtract the second equation from the first: z-zx =1, or z(1-x) =1, or z = 1/(1-x). This completes the proof.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- HOW To Use Jmeter To Load Test T24Document27 pagesHOW To Use Jmeter To Load Test T24Hiếu KoolPas encore d'évaluation

- CH 28 Expenditure Multipliers The Keynesian ModelDocument58 pagesCH 28 Expenditure Multipliers The Keynesian Modelanamshirjeel100% (2)

- ATLAS CYLINDER LUBRICATOR MANUALDocument36 pagesATLAS CYLINDER LUBRICATOR MANUALKaleb Z king webPas encore d'évaluation

- Viscosity IA - CHEMDocument4 pagesViscosity IA - CHEMMatthew Cole50% (2)

- Expenditure Multipliers: ("Notes 7" - Comes After Chapter 6)Document57 pagesExpenditure Multipliers: ("Notes 7" - Comes After Chapter 6)hongphakdeyPas encore d'évaluation

- FoE Unit IVDocument31 pagesFoE Unit IVDr Gampala PrabhakarPas encore d'évaluation

- Economic Module 15Document20 pagesEconomic Module 15PatrickPas encore d'évaluation

- The Multiplier Model ExplainedDocument35 pagesThe Multiplier Model ExplainedannsaralondePas encore d'évaluation

- How the Multiplier Model Explains Changes in OutputDocument35 pagesHow the Multiplier Model Explains Changes in OutputannsaralondePas encore d'évaluation

- Lect 10Document24 pagesLect 10api-3857552Pas encore d'évaluation

- What Exactly Is The Multiplier Model?Document32 pagesWhat Exactly Is The Multiplier Model?annsaralondePas encore d'évaluation

- University of The Philippines School of Economics: Study Guide No. 2Document5 pagesUniversity of The Philippines School of Economics: Study Guide No. 2Djj TrongcoPas encore d'évaluation

- Expenditure Multipliers: The Keynesian Model: Economics 102 Jack WuDocument25 pagesExpenditure Multipliers: The Keynesian Model: Economics 102 Jack WuhongphakdeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Parkinmacro11 1300Document19 pagesParkinmacro11 1300Mr. JahirPas encore d'évaluation

- Income, Consumption, Savings & InvestmentDocument23 pagesIncome, Consumption, Savings & InvestmentAurongo NasirPas encore d'évaluation

- Lec 4 (Expenditure Multipliers and Keynesian Model - CH 28)Document58 pagesLec 4 (Expenditure Multipliers and Keynesian Model - CH 28)AbdulPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumption Function and MultiplierDocument24 pagesConsumption Function and MultiplierVikku AgarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- ECON 1002 NOTES ON CHAPTERS 15-17Document52 pagesECON 1002 NOTES ON CHAPTERS 15-17sashawoody167Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 8 Notes Aggregate Expenditure ModelDocument14 pagesChapter 8 Notes Aggregate Expenditure ModelBeatriz CanchilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Macroeconomics 13th Edition Parkin Solutions ManualDocument19 pagesMacroeconomics 13th Edition Parkin Solutions Manualdencuongpow5100% (25)

- Macro Note CardsDocument18 pagesMacro Note CardsSankar AdhikariPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 10 Review Questions and AnswersDocument18 pagesChapter 10 Review Questions and Answersshygirl7646617100% (1)

- Kynes Multiplier1Document22 pagesKynes Multiplier1the superstarPas encore d'évaluation

- National Income and Price DeterminationDocument104 pagesNational Income and Price Determinationhassankazimi23Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Multiplier Describes The Response of Output (GDP) To An Autonomous Change in SpendingDocument7 pagesThe Multiplier Describes The Response of Output (GDP) To An Autonomous Change in SpendingNathan Cedric TankusPas encore d'évaluation

- 2.4. National IncomeDocument9 pages2.4. National Incomevikshit45Pas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Consumption and Aggregate SupplyDocument9 pagesUnderstanding Consumption and Aggregate SupplySamia AfrinPas encore d'évaluation

- What Determines The Demand ForDocument25 pagesWhat Determines The Demand ForSuruchi SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- ChapterDocument42 pagesChapterIf'idatur rosyidahPas encore d'évaluation

- The Income Consumption / Income Saving RelationshipDocument13 pagesThe Income Consumption / Income Saving Relationshipkam_bruisterPas encore d'évaluation

- B.eco Assignment SolutioinDocument6 pagesB.eco Assignment SolutioinShankarkumarPas encore d'évaluation

- MultiplierDocument16 pagesMultiplierNaman LadhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Multiplier EffectDocument8 pagesMultiplier EffectCamille LaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture Note #3Document4 pagesLecture Note #3spadha reddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter Three Aggregate DemandDocument19 pagesChapter Three Aggregate DemandLee HailuPas encore d'évaluation

- Aggregate Expenditure and Equilibrium OutputDocument69 pagesAggregate Expenditure and Equilibrium OutputhongphakdeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Q. 1 Construct A Simplified Model of An Economic System and Explain The Circular Flow of Income. AnsDocument17 pagesQ. 1 Construct A Simplified Model of An Economic System and Explain The Circular Flow of Income. AnsMuhammad NomanPas encore d'évaluation

- Economics AssianmentDocument5 pagesEconomics Assianmentsultana nasirPas encore d'évaluation

- Circular Flow of EconomyDocument19 pagesCircular Flow of EconomyAbhijeet GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of Reduced Consumer ConfidenceDocument8 pagesEffects of Reduced Consumer Confidencewen niPas encore d'évaluation

- Total Cost in The Long-Run and The Isocost LineDocument11 pagesTotal Cost in The Long-Run and The Isocost LineSamia AfrinPas encore d'évaluation

- AE Model Explained: Calculating Equilibrium IncomeDocument23 pagesAE Model Explained: Calculating Equilibrium IncomeHerrika Red Gullon Rosete0% (1)

- EconomicsDocument17 pagesEconomicschiaraghezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Three Basic Macroeconomics RelationshipDocument5 pagesThe Three Basic Macroeconomics RelationshipNicole Echanes0% (1)

- Chapter 8Document11 pagesChapter 8Neelabh KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Expenditure Multipliers: The Keynesian Model : Key ConceptsDocument15 pagesExpenditure Multipliers: The Keynesian Model : Key ConceptsTiffany SmithPas encore d'évaluation

- Topic 5 - Output and The Exchange Rate in The Short RunDocument17 pagesTopic 5 - Output and The Exchange Rate in The Short Runrayyan Al shiblyPas encore d'évaluation

- Review Questions - Chapter 18Document6 pagesReview Questions - Chapter 18Thabiso NgcoboPas encore d'évaluation

- Macroeconomics - Keynesian ModelsDocument22 pagesMacroeconomics - Keynesian ModelsAlfa RydesterPas encore d'évaluation

- A2 - The Circular Flow of IncomeDocument7 pagesA2 - The Circular Flow of IncomeDamion BrusselPas encore d'évaluation

- Determination of GDP in The Short RunDocument38 pagesDetermination of GDP in The Short Runhhhhhhhuuuuuyyuyyyyy0% (1)

- © 2010 Pearson Addison-WesleyDocument52 pages© 2010 Pearson Addison-WesleyhongphakdeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Solution Manual Macroeconomics Robert J Gordon The Answers From The Book On Both The Questions and The Problems Chapter 3Document6 pagesSolution Manual Macroeconomics Robert J Gordon The Answers From The Book On Both The Questions and The Problems Chapter 3Eng Hinji RudgePas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture - 3 - 4 - Determination of Economic ActivityDocument61 pagesLecture - 3 - 4 - Determination of Economic ActivityAnil KingPas encore d'évaluation

- Parkinmacro11 (28) 1200Document19 pagesParkinmacro11 (28) 1200nikowawa100% (1)

- The Simple Keynesian Model of Income Determination ExplainedDocument60 pagesThe Simple Keynesian Model of Income Determination ExplainedRakesh Seela100% (2)

- Macro-Economics Assignments Provide Insights into Circular Flow and Multiplier ConceptsDocument23 pagesMacro-Economics Assignments Provide Insights into Circular Flow and Multiplier ConceptsMoh'ed A. KhalafPas encore d'évaluation

- Economics and Personal TatementDocument7 pagesEconomics and Personal Tatementsultana nasirPas encore d'évaluation

- Task M2Document3 pagesTask M2bendermacherrickPas encore d'évaluation

- Eco202 Exam ReviewDocument5 pagesEco202 Exam Reviewaoi.ishigaki101Pas encore d'évaluation

- Module 14 A Simple Model of Income DeterminationDocument6 pagesModule 14 A Simple Model of Income DeterminationPatrickPas encore d'évaluation

- Definitions: Consumption FunctionDocument10 pagesDefinitions: Consumption FunctionparnasabariPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Economics: Business Strategy & Competitive AdvantageD'EverandBusiness Economics: Business Strategy & Competitive AdvantagePas encore d'évaluation

- Abaro Himu Humayun AhmedDocument39 pagesAbaro Himu Humayun AhmedKhaled Hassan100% (4)

- ACCAReloaded ACCA Syllabus Changes PDFDocument14 pagesACCAReloaded ACCA Syllabus Changes PDFpiyalhassan0% (1)

- 52ef78554261c-ICC World T20 Bangladesh 2014 Ticketing Policy - FAQ Phase 2Document8 pages52ef78554261c-ICC World T20 Bangladesh 2014 Ticketing Policy - FAQ Phase 2Md ShohagPas encore d'évaluation

- 52ef78554261c-ICC World T20 Bangladesh 2014 Ticketing Policy - FAQ Phase 2Document8 pages52ef78554261c-ICC World T20 Bangladesh 2014 Ticketing Policy - FAQ Phase 2Md ShohagPas encore d'évaluation

- F7 NoteDocument3 pagesF7 NoteMd ShohagPas encore d'évaluation

- LatterDocument1 pageLatterMd ShohagPas encore d'évaluation

- Sa Mar11 F6uk OverseasDocument5 pagesSa Mar11 F6uk OverseasPawan_Vaswani_9863Pas encore d'évaluation

- Xbox Accessories en ZH Ja Ko - CN Si TW HK JP KoDocument64 pagesXbox Accessories en ZH Ja Ko - CN Si TW HK JP KoM RyuPas encore d'évaluation

- GooglepreviewDocument69 pagesGooglepreviewtarunchatPas encore d'évaluation

- 236b3 Esquema Electrico Mini Cargador CatDocument29 pages236b3 Esquema Electrico Mini Cargador Cathenry laviera100% (2)

- Mobile-Friendly Cooperative WebDocument7 pagesMobile-Friendly Cooperative WebWahyu PPas encore d'évaluation

- TG KPWKPDocument8 pagesTG KPWKPDanmar CamilotPas encore d'évaluation

- Advisory Circular: Aircraft Maintenance Engineer Licence - Examination Subject 2 Aircraft Engineering KnowledgeDocument44 pagesAdvisory Circular: Aircraft Maintenance Engineer Licence - Examination Subject 2 Aircraft Engineering KnowledgejashkahhPas encore d'évaluation

- Rustia V Cfi BatangasDocument2 pagesRustia V Cfi BatangasAllen GrajoPas encore d'évaluation

- Upper Six 2013 STPM Physics 2 Trial ExamDocument11 pagesUpper Six 2013 STPM Physics 2 Trial ExamOw Yu Zen100% (2)

- 2000 T.R. Higgins Award Paper - A Practical Look at Frame Analysis, Stability and Leaning ColumnsDocument15 pages2000 T.R. Higgins Award Paper - A Practical Look at Frame Analysis, Stability and Leaning ColumnsSamuel PintoPas encore d'évaluation

- Communication & Collaboration: Lucy Borrego Leidy Hinojosa Scarlett DragustinovisDocument44 pagesCommunication & Collaboration: Lucy Borrego Leidy Hinojosa Scarlett DragustinovisTeacherlucy BorregoPas encore d'évaluation

- Learner's Activity Sheet: English (Quarter 4 - Week 5)Document5 pagesLearner's Activity Sheet: English (Quarter 4 - Week 5)Rufaidah AboPas encore d'évaluation

- Demo TeachingDocument22 pagesDemo TeachingCrissy Alison NonPas encore d'évaluation

- French Revolution ChoiceDocument3 pagesFrench Revolution Choiceapi-483679267Pas encore d'évaluation

- Specification: F.V/Tim e 3min 5min 8min 10MIN 15MIN 20MIN 30MIN 60MIN 90MIN 1.60V 1.67V 1.70V 1.75V 1.80V 1.85VDocument2 pagesSpecification: F.V/Tim e 3min 5min 8min 10MIN 15MIN 20MIN 30MIN 60MIN 90MIN 1.60V 1.67V 1.70V 1.75V 1.80V 1.85VJavierPas encore d'évaluation

- Nurses Week Program InvitationDocument2 pagesNurses Week Program InvitationBenilda TuanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Acl Data Analytics EbookDocument14 pagesAcl Data Analytics Ebookcassiemanok01Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1-2-Chemical Indicator of GeopolymerDocument4 pages1-2-Chemical Indicator of GeopolymerYazmin Alejandra Holguin CardonaPas encore d'évaluation

- Macbeth Introduction0Document40 pagesMacbeth Introduction0MohammedelaminePas encore d'évaluation

- New Wordpad DocumentDocument6 pagesNew Wordpad DocumentJonelle D'melloPas encore d'évaluation

- MATH 8 QUARTER 3 WEEK 1 & 2 MODULEDocument10 pagesMATH 8 QUARTER 3 WEEK 1 & 2 MODULECandy CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Starting an NGO - A Guide to the Key StepsDocument22 pagesStarting an NGO - A Guide to the Key StepsBadam SinduriPas encore d'évaluation

- ATB Farmacología 2Document194 pagesATB Farmacología 2Ligia CappuzzelloPas encore d'évaluation

- Harajuku: Rebels On The BridgeDocument31 pagesHarajuku: Rebels On The BridgeChristian Perry100% (41)

- Limit Switch 1LX7001-J AZBILDocument8 pagesLimit Switch 1LX7001-J AZBILHoàng Sơn PhạmPas encore d'évaluation

- Eco 301 Final Exam ReviewDocument14 pagesEco 301 Final Exam ReviewCảnh DươngPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1-The Indian Contract Act, 1872, Unit 1-Nature of ContractsDocument10 pagesChapter 1-The Indian Contract Act, 1872, Unit 1-Nature of ContractsALANKRIT TRIPATHIPas encore d'évaluation