Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Competitive Intelligence: Paul Gray

Transféré par

Satyendra PandeyDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Competitive Intelligence: Paul Gray

Transféré par

Satyendra PandeyDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

CoMPETITIvE InTELLIGEnCE

Competitive Intelligence

Paul Gray Abstract

Competitive intelligence (CI) is the gathering and use of knowledge about the external environment in which firms operate. This article explains what CI is, the CI process, how to obtain the needed data, the available techniques, and how CI is used. After describing the generic CI cycle, we elaborate on what is actually done. Competitive intelligence is a process that increases marketplace competitiveness by analyzing the capabilities and potential actions of individual competitors as well as the overall competitive situation of the firm in its industry and in the economy. This article considers the need for counterintelligence to reduce a firms vulnerabilities, as well as the ethical context in which competitive intelligence work is done.

Paul Gray is Professor Emeritus of Information Science at Claremont Graduate university and the author of Managers Guide to Making Decisions About Information Systems (John Wiley & Sons, 2005). paul.gray@cgu.edu

Introduction

Strategy, marketing, financein fact, any aspect of planning and decision-makinginvolves considering the competition. What are they doing? What are they likely to do? How do the economy, laws, and government actions affect themand us? Most business intelligence focuses on fact-based decision making that is based principally on understanding and using internal factors. Competitive intelligence is concerned with the external factors that affect the companyin other words, what goes on outside the companys walls. Some firms use simplistic external inputs such as executive gut feel, reading trade journals, or gossip from sales people. In sophisticated firms, competitive intelligence (CI) is the responsibility of a separate staff. We will present an overview of CI, explain what CI is, the CI process, how to obtain the needed data, the available techniques, how CI is used, where it fits in the organization, and its ethics. We will begin by describing the CI cycle and then elaborate on what is actually done.

BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE Journal vol. 15, no. 4

31

CoMPETITIvE InTELLIGEnCE

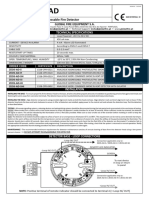

Collect internal

Data Compile Collect external

Information Analyze

Knowledge

Intelligence Apply

Decision Act and observe

Results

Select and communicate

Figure 1. The competitive intelligence process

overview

Competitive intelligence is a process that enhances marketplace competitiveness by understanding individual competitors as well as the overall competitive situation of the firm in its industry. This is not spy versus spy. You can use whatever you find in the public domain:

A more formal definition comes from the Society of Competitive Information Professionals (www.scip.org): CI is a systematic and ethical program for gathering, analyzing, and managing external information that can affect your companys plans, decisions, and operations.

Government information Web pages and advertisements Online databases Journals and newspapers Interviews and surveys Financial reports Trade shows Executive speeches Competitors, suppliers, distributors, and customers

How Competitive Intelligence is Used

The role of CI analysts is to distill, analyze, and present the information gathered so it is in an actionable form for management. CI supplies the inputs that tell managers what they need to know about current and future competition, including their own organizations strengths and weaknesses, financials, major clients, what detailed inspection reveals about existing products in the marketplace, what new technologies (particularly disruptive technologies) are on the horizon, how competitors responded to your previous initiatives, competitor strengths and weaknesses, and more. The objective is to obtain an edge on your competitors and to defend your firm against their efforts. The operating principle is be forewarned so you are forearmed.

What you cant do is take your binoculars and look into your competitors plant in the middle of the night, or pay a competitors employee to funnel internal documents or specifications to you. It turns out that the problem is not that information is lacking, but that there is too much information. Companies (including your own) use Web pages, press releases, and whatever other means of publicity they can afford to make their products visible and to inflate their stock prices. In other words, they brag and they blab, often when they shouldnt. Sometimes they lie. In CI, the task is to gather all of this information and assemble it into a coherent whole so that senior managers in your firm can understand what competitors are doing and planning. Remember that CI is a two-sided game; you can be sure that your competitors are gathering and analyzing data about your firm, too.

The CI Process

Figure 1 shows the CI process and how it is related to both business intelligence (BI) and knowledge management (KM). Business intelligence is used to find and analyze data about the firm from its various data sources and repositories. That data is mostly internal and about firm operations. Knowledge management involves collecting, codifying, and disseminating the intellectual capital of the firm. Knowledge is both explicit (e.g., facts you can record such as a competitors reported revenue) and tacit,

32

BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE Journal vol. 15, no. 4

CoMPETITIvE InTELLIGEnCE

but only explicit knowledge can be dealt with routinely in knowledge management. BI and KM (see the first three steps in Figure 1) are both inputs to competitive intelligence. Competitive intelligence adds collecting and analyzing external data, selecting knowledge, and then communicating it to decision makers. The decision makers, in turn, act and observe the results. Figure 1 does not show the feedback that can occur along the way, such as decision makers going back to the CI analysts to obtain more data or more knowledge.

Competitor intelligence is much narrower than competitive intelligence. It applies to analyses of individual firms. Here you want to know what each of your competitors is doing and to use that information to compete with them. The typical approach is to create individual competitor profiles to examine their strengths and weaknesses and identify your opportunities and threats (see SWOT Analysis below). J. Robert Oppenheimers insight applies: The real secrets are not the facts of nature but the intentions of men. That is, in a stable situation, you are as interested (perhaps even more interested) in what competitors will do in the future than what they are doing now. You need to learn about their strategies, their current and forthcoming products, their finances, their alliances (joint ventures, mergers, acquisitions), and their people. Simple things help here. For example:

Competitive Intelligence versus Competitor Intelligence

CI can be divided into two classes: competitive intelligence and competitor intelligence. Competitive intelligence involves finding out about the state of the world as it affects your firm. Some examples include:

Monitor a competitors personnel ads to find out if they are trying to hire people with different skills than those possessed by their current staff, possibly so they can enter your markets or employ new technologies. Do what the auto industry does: Buy one each of a competitors products and tear them down to see where they produce equivalent parts at lower costs than you incur. Visit competitors booths at trade shows, read press releases, trade press interviews with their key people, and look at their product ads to gain information about their forthcoming products.

Are new technologies emerging that will be disruptive for your present and future products? Are consumer/customer tastes changing, and what does that mean for your offerings? Are new markets (e.g., market segments, countries) opening up in which your firms product can and should compete? Are the demographics in your sales areas shifting favorably or unfavorably? How will pending legislation, regulations, or taxes change your revenue streams?

CI Techniques

Several techniques are available for developing competitive knowledge, including:

Note that many of the answers to these questions apply to your industry competitors as well as to your own firm. However, relying on your industry association for answers is not enough, because associations supply the same information to all their members. Your management wants to know how your firm will be affected.

SWOT Competitor profiles Environmental scanning Modeling, PEST Industry analysis Financial analysis Win/loss analysis

BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE Journal vol. 15, no. 4

33

CoMPETITIvE InTELLIGEnCE

Scenarios War gaming

We will briefly discuss each of these approaches. SWOT Analysis The simplest form of competitor analysis, called SWOT, involves evaluating an individual competitor. SWOT is an acronym that stands for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Taught widely in business schools, SWOT is a sequence of steps taken to analyze a competitor. The idea is to start with an environmental scan (described below) in which you find out (or take what you know) about a competitor and go through the four analysis steps listed. You evaluate the competitors strengths (e.g., brand, distribution, sales) and weaknesses (e.g., high cost structure, weak Internet presence) and use that information to find opportunities for your firm in the marketplace and to recognize threats posed by the competitors capabilities. For many firms, particularly those without CI capabilities, SWOT analysis is the sum total of their competitor intelligence. The SWOT format is also a useful way to present results to non-quantitative managers, even when you use much more sophisticated analyses. Competitor Profiles The input to SWOT analysis is a competitor profile, that is, a current dossier about the competitor. Much of this information, such as the mission statement, can be obtained from the competitors Web site and, if it is a public company, from its 10K filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission. There are other details that may not be as public and require research on your part. What are their patents, trademarks, and brand? What products do they offer, and what is the product quality, level of after-sale service, and method of distribution? What is the measure of their customer loyalty? In what locations do they dominate or lag? How do they source and outsource? Who are their managers, and how do they make decisions? What are their financial strengths and weaknesses?

Profiles need to be kept up to date and should include firms that are potential competitors even if they are not currently in your space. As you profile competitors, be sure to honestly assess their success factors and compare them to your enterprises strengths and weaknesses. Environmental Scanning No, environmental scanning does not refer to determining whether the surroundings are green enough. Unlike SWOT, which deals with individual competitors, environmental scanning is about understanding what is going on in the world both inside and outside your industry. It is best performed continually. Environmental scans study the macro environment, including the economy, government actions and finances, the impact of legal decisions, demographics and attitudes, labor supplies and materials sources, and the impacts of internal and external stakeholders. Perhaps the most widely used environmental scanning model is PEST.

Modeling and PeST/STeePLeD

PEST (political, economic, social, technological) analysis models macro-environmental factors. PEST is often extended to include combinations of legal, environmental, education, and demographic factors, in which case the acronym is extended. If all are used, the acronym becomes STEEPLED. The choice of factors depends on the skill set of the firm, its environment, and the funds available for the analysis. PEST is not the only modeling technique. Some firms use Porters Five Forces model (Porter, 1998); others (particularly in marketing) use conjoint analysis models. The latter is a statistical technique for determining how people value different features that make up an individual product or service. The objective of conjoint analysis is to determine the trade-offs in what combination of a limited number of attributes is most influential on respondent choice or decision making. Software is available from SAS (http://support.sas.com/resources/ papers/tnote/tnote_marketresearch.html). Industry Analysis Industry analysis is a form of environmental scanning but is limited to studies of individual industries. For

34

BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE Journal vol. 15, no. 4

CoMPETITIvE InTELLIGEnCE

most industries, detailed reports are available for a fee from consulting firms. These are usually much more cost-effective than trying to do the whole job yourself. Keeping up with the trade press is also useful. Financial Analysis Financial analysis is part of environmental scanning and industry analysis. The goal is to assess competitors past and future performance, financial stability, and potential bankruptcy. Because it requires finance skills, competitor financial analysis should be done by the accounting or finance departments as part of their routine duties. Win/Loss Analysis Win/loss analysis is a postmortem performed after a major potential business-to-business or business-togovernment sale is won or lost. The objective is to find out why the particular result occurred. It involves assessment of the winners offering (e.g., lower in price? higher in quality?) compared to your own and/or that of others. Such analyses must be brutally honest if you are to learn. There are (expensive) third-party consultants specializing in such analyses who often can find out what really happenedrather than the courteous but uninformative answers you often get from potential clients. Scenarios Scenarios are stories about the implications of alternative choices. They provide a way to communicate with managers and non-experts. Scenarios are used to describe consequences for the firm and its competitors based on choices the organization and/or its competitors can make. For example, after the Sarbanes-Oxley act was passed by the U.S., foreign companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges had several choices, including:

The scenario approach is a useful tool to investigate possibilities. Although scenarios are not predictions of what will be, they do describe some of the situations that might evolve. To create a scenario:

Select the key variables of interest and estimate their values and probabilities for you and your competitors under different sets of assumptions. The assumptions (e.g., level of GNP growth, timing of technological developments, competitor response) form a scenario space. The output of CI analysis can be used to generate scenarios. Each scenario must be possible, plausible, and internally consistent.

Scenarios provide the basis for determining the mismatches between current policy and anticipated (future) situations and point to options that guard against undesirable outcomes. War Gaming Whereas scenarios produce alternative futures based on changes in assumptions, war games are multi-player simulations in which members of the firm form several teams, each representing a particular role. For example, one team represents (or is) the firms management. Other teams represent main competitors, stakeholders, and the market. One team starts the simulation by introducing a change in the status quo (e.g., a new product or a merger). The other teams respond to the change; some take counter-actions; others accept the change. The game typically involves multiple rounds of action and reaction. War games are used to understand threats from current and future competitors, changes in the external environment, and disruptive technologies. They also bring insight into the long-term effects of a particular decision, including strategic opportunities.

Retrofit their information systems to comply with the new regulations. Gradually move their stocks to other exchanges. (The decision to move had to take into account the financial impact of doing so and the possibility that nonU.S. stock exchanges would follow the SarbanesOxley model.)

Protecting yourself: Counter Intelligence

Just as you perform competitive intelligence about other firms, they will perform competitive intelligence about you. Just as they have a need to advertise and market themselves, you need to get the word out about what you

BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE Journal vol. 15, no. 4

35

CoMPETITIvE InTELLIGEnCE

do and what you can do. You must not disclose too much; restrict information flow wherever possible. If you are a public company, there is a minimum of information that you must divulge in your 10K reports to the government. However, you are under no obligation to do more. The more you divulge, the more your competitors can find out about you. Oppenheimers advice abovethat your real secrets are your intentionsalso applies here. Avoid talking about what you plan in internal publications; they can get to the public. Make it a standard for your employees to decline to answer unexpected questions. Indoctrinate managers and your senior employees that bragging and blabbing are forbidden. Even if youre not a government contractor required to maintain security, remember the World War II slogan, the walls have ears. Because information is squirreled away on your firms computers, keep information about your plans and intentions as safe as, if not safer than, your customer data. What the software industry calls vaporware can be used as a way to deflect the competition. Vaporware is the public announcement of future products that you intend (or dont intend) to market in the near term. Observing competitive responses can help you understand whether investing in the vaporwares ideas is worthwhile. Finally, studying yourself as you would competitors will help you identify what competitors will look for and hence what you need to protect.

Ethics

The nature of competitive intelligence exposes CI analysts to ethical dilemmas, both in the work they do and in tasks assigned to them. An ethical code is prescribed by their professional organization, the Society for Competitive Intelligence Professionals (www.scip.org). Analysts must, of course, comply with applicable laws such as the Uniform Trade Secrets Act (approved by 46 states) and the U.S. Espionage Act of 1996, and must respect their own firms proprietary rules about information. They should tell the truth, use their own names and affiliations when making inquiries or interviewing, and do fact checking. Hacking, dumpster diving, physical intrusion of a competitors facilities, and bribery may be tempting but are not ethical and are almost always illegal.

Uses and Examples

Competitive intelligence is used for marketing and sales, public relations and customer management, and making strategic decisions. The decision to alter strategy, for example, requires CI input when there are changes in the business environment, proposals for mergers or acquisitions, or new competitors. Although companies and governments are secretive about their competitive intelligence activities, some consulting firms (many in the UK) do publish case examples on the Web, some only in capsule form. As you would expect, these cases, being advertising for the firms, all show positive results and are concerned with specific competitor intelligence. Here are a few examples. A Credit Union A credit union with high operating costs was facing stiff competition from local banks with lower operating costs. The staff ran CI on their local competitors to find a competitive strategy. They developed an intelligence database that included, among other things, competitive data that was known by their own employees; third-party interviews with competitors; want ads that appeared regularly in the local newspaper; competitor 10K forms; results of satisfaction surveys (run on their own and their competitors depositors); purchased industry, marketing, and forecasting data; and demographic forecasts from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Staffing

CI groups are most often found in large (e.g., Fortune 500) firms. However, for some small firms, a single individual may be charged with the CI task, or it may be assigned to BI analysts. There are estimates that CI is performed at some level by 80 percent to 90 percent of firms, either through in-house groups, outsourcing, or consulting firms hired for specific tasks. The required skills include being able to find competitive information, to analyze what is found, and to communicate findingsthat is, the ability to convert results into a form that can be understood by managers. A comprehensive discussion of starting a CI group is found in Sawka and Hohhof (2008; References).

36

BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE Journal vol. 15, no. 4

CoMPETITIvE InTELLIGEnCE

From their analysis, the credit union concluded that its competitors depositors were disgruntled by the way the banks were treating them. They hired marketers and advertised their alternative service philosophy and the personal services they provided. As a result, membership grew and economies of scale helped to reduce operating costs (http://www.burkhardtresearch.com/ci_study.html). Johnson & Johnson Decades ago in 1975, Johnson & Johnson used competitive intelligence to defend Tylenol against a new competitor. This case occurred before the Tylenol crisis in 1982 when six people died of cyanide-laden capsules. Tylenol, which had fewer side effects than competing aspirin products, charged a premium. In 1975, Bristol-Myers introduced an equivalent product, Datril, which was to be marketed as just as good as Tylenol, but cheaper. The company received early warning of the competition when a manager visiting a printing plant found a Datril marketing brochure being produced. He recognized the importance of the find and notified the Tylenol marketing managers. Through their CI group they knew that Bristol-Myers tested all new products in Peoria, IL, and Albany, NY. They sent multiple observers into the test markets and identified Datrils market penetration strategy, approaches, and timing. They cut the Tylenol price by 30 percent, and warned Bristol-Myers and the media that Datril could not claim a price advantage. Datril didnt make it as a competitor. This example is considered a landmark of the blockmarketing strategy. Its success was due in part to Bristol-Myers not having a counterintelligence strategy at the time. Although the price reduction cut short-term profits by millions, Tylenol gained long-term market share (http://onlinembastudy.blogspot.com/2010/05/johnsonjohnson-successful-competitive.html). Consultancies A UK consultancy was hired to find out the launch date of a competitors product. They determined the date by interviewing journalists, the competitors PR and advertising agencies, packaging suppliers, and

retailers who sell the competitors products (http://www. marketing-intelligence.co.uk/pubs/cases/case1.htm). To find out about a competitors capacity and capabilities at a regional warehouse, a different UK consultancy spoke with the warehouse workers on a Sunday morning without identifying themselves (an approach considered unethical in the U.S.). They found that the competitors warehouse capacity could not supply demand in the region. The firm expanded its own warehouse to fill the gap (http://www.marketing-intelligence.co.uk/pubs/cases/ case3.htm).

Summary

The role of competitive intelligence is to support management in the decision-making process. CI, when done ethically, is the process of ensuring marketplace competitiveness through legal means. It requires understanding both the overall external competitive environment and individual competitors. It also involves protecting your own firm against your competitors CI. In performing CI, you can use whatever you find in the public domain, your own internal data, purchased data, and analyses. The goal is to make sure that you are not surprised by existing competitors, potential competitors, or disruptive technologies. Many analysis techniques are available, such as those described in this paper. Although in many aspects the work is similar to what is done in business intelligence, CI concentrates on what is going on outside the firm.

References

Porter, Michael E. [1998]. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, New York, NY: Free Press. Sawka, Kenneth, and B. Hohhof, eds. [2008]. Starting a Competitive Analysis Function, Alexandria, VA: Competitive Intelligence Foundation.

BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE Journal vol. 15, no. 4

37

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- CIDocument11 pagesCImehdi androidPas encore d'évaluation

- Term Paper Competitive Intelligence (CI)Document5 pagesTerm Paper Competitive Intelligence (CI)Joseph FawzyPas encore d'évaluation

- Competitive IntelligenceDocument56 pagesCompetitive IntelligenceYannickEkaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Competitive Intelligence 2Document5 pagesCompetitive Intelligence 2Monil JainPas encore d'évaluation

- Definition of Competitive IntelligenceDocument3 pagesDefinition of Competitive IntelligenceSAYMON ISABELO SARMIENTOPas encore d'évaluation

- Competitive Intelligence - An Overview: What Is Ci?Document14 pagesCompetitive Intelligence - An Overview: What Is Ci?Hector OliverPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Intelligence in MNCsDocument11 pagesMarketing Intelligence in MNCsSasikala DayalanPas encore d'évaluation

- Competitive Intelligence (BUSINESS ETHICS)Document8 pagesCompetitive Intelligence (BUSINESS ETHICS)Meghan CrossPas encore d'évaluation

- Competitive IntelligenceDocument18 pagesCompetitive IntelligenceAjay GhaiPas encore d'évaluation

- CI - Final Exam - Radwa Mohamed Fayez - Fall21 CI 04Document5 pagesCI - Final Exam - Radwa Mohamed Fayez - Fall21 CI 04wafaa mustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing IntelligenceDocument8 pagesMarketing Intelligenceram talrejaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ci JugaDocument12 pagesCi Jugadanang widodoPas encore d'évaluation

- Competitor AnalysisDocument12 pagesCompetitor AnalysiskiranaishaPas encore d'évaluation

- Analytics An Imperative For Sustaining and DifferentiatingDocument23 pagesAnalytics An Imperative For Sustaining and Differentiatingsffr28Pas encore d'évaluation

- Entrepreneurship Unit 03Document13 pagesEntrepreneurship Unit 03SurajPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Gather Market IntelligenceDocument23 pagesHow To Gather Market IntelligencemuhammadshoaibarifPas encore d'évaluation

- Market IntelligenceDocument16 pagesMarket IntelligencePopa AlinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic MarketingDocument52 pagesStrategic MarketingAnkit Sharma 028Pas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Burger KingDocument26 pagesMarketing Burger KingWaqar Javed100% (1)

- Marketing Intelligence: Types of Intelligence SourcesDocument5 pagesMarketing Intelligence: Types of Intelligence Sourceskanij fatema tinniPas encore d'évaluation

- ESLSCA MBA G40 CI Term Paper Mostafa Omar AzmyDocument6 pagesESLSCA MBA G40 CI Term Paper Mostafa Omar Azmymostafaazmy0% (1)

- CERIAS Tech Report 2011-10 Industrial Espionage or Competitive Intelligence: Two Sides of The Same CoinDocument14 pagesCERIAS Tech Report 2011-10 Industrial Espionage or Competitive Intelligence: Two Sides of The Same CoinMargarita NardoPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Essential Steps For A Successful Strategic Marketing ProcessDocument18 pages5 Essential Steps For A Successful Strategic Marketing ProcessJack 123Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson TopicDocument33 pagesLesson Topicrocky thakurPas encore d'évaluation

- ANK B2B CInt 16 12 10Document44 pagesANK B2B CInt 16 12 10Alok SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Excellence in Financial ManagementDocument36 pagesExcellence in Financial Managementمهنوش جوادی پورفرPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 5Document20 pagesChapter 5Ahmed HonestPas encore d'évaluation

- EtopDocument7 pagesEtopAnilBahugunaPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is A Situation AnalysisDocument4 pagesWhat Is A Situation AnalysisalvinPas encore d'évaluation

- SWOT AnalysisDocument6 pagesSWOT AnalysisJPIA Scholastica DLSPPas encore d'évaluation

- SWOT AnalysisDocument6 pagesSWOT AnalysisJPIA Scholastica DLSPPas encore d'évaluation

- BPL - Unit 03 - Market Research and Competitve LandscapeDocument10 pagesBPL - Unit 03 - Market Research and Competitve LandscapeSuresh SubramaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Swot: Project Guidelines: Dev Shroff Std-12 Div.-D Roll No.Document36 pagesSwot: Project Guidelines: Dev Shroff Std-12 Div.-D Roll No.rgembkfmvkrevm jrogj gygrgnhughn rn njh gklhglutrPas encore d'évaluation

- Sony (Fob)Document8 pagesSony (Fob)N. QuỳnhPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Essential Steps For A Successful Strategic Marketing ProcessDocument26 pages5 Essential Steps For A Successful Strategic Marketing ProcessKARTHICK SPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Market Research? Definition and Types - Emeritus IndiaDocument13 pagesWhat Is Market Research? Definition and Types - Emeritus IndiaKiandra MaynardPas encore d'évaluation

- Create An Intelligence Program For Current and Future Business NeedsDocument8 pagesCreate An Intelligence Program For Current and Future Business NeedsWallacyyyPas encore d'évaluation

- International Marketing Research - DocDocument19 pagesInternational Marketing Research - DocSachitChawla100% (1)

- Psda 2 CiDocument11 pagesPsda 2 Cimittal anuragPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Essential Steps For A Successful Strategic Marketing ProcessDocument26 pages5 Essential Steps For A Successful Strategic Marketing ProcessKARTHICK SPas encore d'évaluation

- The Market Driven Organization: Understanding, Attracting, and Keeping Valuable CustomersD'EverandThe Market Driven Organization: Understanding, Attracting, and Keeping Valuable CustomersPas encore d'évaluation

- Social EntrepreneurDocument24 pagesSocial Entrepreneurkent aro doromalPas encore d'évaluation

- External Assessment-Strategic Management.Document3 pagesExternal Assessment-Strategic Management.Dominic E. BoticarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Competitive IntelligenceDocument69 pagesCompetitive IntelligencekaranPas encore d'évaluation

- BUS7B64 Assignment (1) - Edit ItDocument7 pagesBUS7B64 Assignment (1) - Edit ItGrammarianPas encore d'évaluation

- Final RP 2 Draft BBA-HonsDocument29 pagesFinal RP 2 Draft BBA-HonsAnonymous 0JNjBIPas encore d'évaluation

- Tailoring Competitive Intelligence To Executives' NeedsDocument26 pagesTailoring Competitive Intelligence To Executives' Needsanon_137707045Pas encore d'évaluation

- Getting The Best Out of Your CustomersDocument24 pagesGetting The Best Out of Your Customersadedoyin123Pas encore d'évaluation

- Business Environment - Surf Excel - ShaheeraDocument19 pagesBusiness Environment - Surf Excel - ShaheeraShaheera100% (1)

- Chapter 3Document12 pagesChapter 3Kaleab TessemaPas encore d'évaluation

- Scanning The Business EnvironmentDocument40 pagesScanning The Business EnvironmentReiner MagdadaroPas encore d'évaluation

- Competitive Advantage and Internal Organizational AssessmentDocument12 pagesCompetitive Advantage and Internal Organizational AssessmentVish VicPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit-3 Media Audience and Consumer Opinion Data: Segementation Engagement Mesasging MeasurementDocument7 pagesUnit-3 Media Audience and Consumer Opinion Data: Segementation Engagement Mesasging MeasurementApoorv GoelPas encore d'évaluation

- Course12 2 PDFDocument36 pagesCourse12 2 PDFYony LaurentePas encore d'évaluation

- Competitor AnalysisDocument3 pagesCompetitor AnalysisJef De VeraPas encore d'évaluation

- Corporate Public Relations StrategyDocument2 pagesCorporate Public Relations StrategyKanishka GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Competitive Intelligence PSDA-3Document8 pagesCompetitive Intelligence PSDA-3Divisha AgarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Analytics: 7 Easy Steps to Master Marketing Metrics, Data Analysis, Consumer Insights & Forecasting ModelingD'EverandMarketing Analytics: 7 Easy Steps to Master Marketing Metrics, Data Analysis, Consumer Insights & Forecasting ModelingPas encore d'évaluation

- Competitor-Intelligence - Dec07 PDFDocument3 pagesCompetitor-Intelligence - Dec07 PDFdestria87Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3. External AssessmentDocument26 pagesChapter 3. External AssessmentLouciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Employment Under Dubai Electricity & Water AuthorityDocument6 pagesEmployment Under Dubai Electricity & Water AuthorityMominur Rahman ShohagPas encore d'évaluation

- API RP 1102 SpreadsheetDocument5 pagesAPI RP 1102 Spreadsheetdrramsay100% (4)

- Stearic Acid MSDSDocument6 pagesStearic Acid MSDSJay LakhaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Jastram Rudder Feedback UnitDocument21 pagesJastram Rudder Feedback UnitGary Gouveia100% (3)

- 1 final-LESSON-1-U1-Humanities-and-Arts-in-the-Western-Concept-dallyDocument10 pages1 final-LESSON-1-U1-Humanities-and-Arts-in-the-Western-Concept-dallyVilla JibbPas encore d'évaluation

- A Microscope For Christmas: Simple and Differential Stains: Definition and ExamplesDocument4 pagesA Microscope For Christmas: Simple and Differential Stains: Definition and ExamplesGwendolyn CalatravaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mbeya University of Science and TecnologyDocument8 pagesMbeya University of Science and TecnologyVuluwa GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Heat ExchangerDocument5 pagesHeat Exchangersara smithPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis and Design of Cantilever Slab Analysis and Design of Cantilever SlabDocument3 pagesAnalysis and Design of Cantilever Slab Analysis and Design of Cantilever SlabMesfinPas encore d'évaluation

- (Dust of Snow) & 2 (Fire and Ice) - NotesDocument3 pages(Dust of Snow) & 2 (Fire and Ice) - NotesdakshPas encore d'évaluation

- Lifestyle Mentor. Sally & SusieDocument2 pagesLifestyle Mentor. Sally & SusieLIYAN SHENPas encore d'évaluation

- Module-2: SolidificationDocument16 pagesModule-2: SolidificationSachin AgnihotriPas encore d'évaluation

- Teacher Empowerment As An Important Component of Job Satisfaction A Comparative Study of Teachers Perspectives in Al Farwaniya District KuwaitDocument24 pagesTeacher Empowerment As An Important Component of Job Satisfaction A Comparative Study of Teachers Perspectives in Al Farwaniya District KuwaitAtique RahmanPas encore d'évaluation

- DOPE Personality TestDocument8 pagesDOPE Personality TestMohammed Hisham100% (1)

- Conventional and Box-Shaped Piled RaftsDocument6 pagesConventional and Box-Shaped Piled RaftsAdrian VechiuPas encore d'évaluation

- SAGC Compliance Awareness-Grid UsersDocument66 pagesSAGC Compliance Awareness-Grid Userskamal_khan85Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nguyen Ngoc-Phu's ResumeDocument2 pagesNguyen Ngoc-Phu's ResumeNgoc Phu NguyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature 101 Assignment: Step 1: Graphic OrganizerDocument2 pagesLiterature 101 Assignment: Step 1: Graphic OrganizercatarinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Job No. 25800: Quebrada Blanca Fase 2Document1 pageJob No. 25800: Quebrada Blanca Fase 2Benjamín Muñoz MuñozPas encore d'évaluation

- 01 Gyramatic-Operator Manual V2-4-1Document30 pages01 Gyramatic-Operator Manual V2-4-1gytoman100% (2)

- A Research Paper On DormitoriesDocument5 pagesA Research Paper On DormitoriesNicholas Ivy EscaloPas encore d'évaluation

- ZEOS-AS ManualDocument2 pagesZEOS-AS Manualrss1311Pas encore d'évaluation

- 688 (I) Hunter-Killer - User ManualDocument115 pages688 (I) Hunter-Killer - User ManualAndrea Rossi Patria100% (2)

- Literature Review Is The Backbone of ResearchDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Is The Backbone of Researchafmzweybsyajeq100% (1)

- Vernacular in Andhra PradeshDocument1 pageVernacular in Andhra PradeshNandyala Rajarajeswari DeviPas encore d'évaluation

- Symptoms and DiseasesDocument8 pagesSymptoms and Diseaseschristy maePas encore d'évaluation

- Mechatronics Course PlanDocument3 pagesMechatronics Course PlanMohammad Faraz AkhterPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Resource Development Multiple Choice Question (GuruKpo)Document4 pagesHuman Resource Development Multiple Choice Question (GuruKpo)GuruKPO90% (20)

- 33392-01 Finegayan Water Tank KORANDO PDFDocument3 pages33392-01 Finegayan Water Tank KORANDO PDFShady RainPas encore d'évaluation

- Disconnect Cause CodesDocument2 pagesDisconnect Cause Codesdungnt84Pas encore d'évaluation