Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Neurología: Stendhal Syndrome: Origin, Characteristics and Presentation in A Group of Neurologists

Transféré par

Srđan RadojčićDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Neurología: Stendhal Syndrome: Origin, Characteristics and Presentation in A Group of Neurologists

Transféré par

Srđan RadojčićDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Neurologa.

2010;25(6):349-356

ISSN: 0213-4853

NEUROLOGA

NEUROLOGA

www.elsevier.es/neurologia

Publicacin Oficial de la Sociedad Espaola de Neurologa

Volumen 25 Nmero 1 Enero-Febrero 2010

Incluida en Index Medicus-MEDLINE, Excerpta Medica/EMBASE, ISI Web of Science, Sciencie Citation Index Expanded, ISI Alerting Services y Neuroscience Citation Index

25 aos

www.elsevier.es/neurologia

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Stendhal syndrome: origin, characteristics and presentation in a group of neurologists

A.L. Guerrero a,*, A. Barcel Rossell b and D. Ezpeleta c

Servicio de Neurologa, Hospital Clnico Universitario de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain Fundaci per lAvan de les Neurocinces, Palma de Mallorca, Spain c Servicio de Neurologa, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Maran, Madrid, Spain

a b

Received on 23rd February 2010; accepted on 25th February 2010

KEYWORDS

Stendhal syndrome; Artistic fruition; Neuroesthetics; Panic attacks; Thought disorders; Affects disorders

Abstract Introduction: Travelling, when searching for knowledge and emotion, can cause psychic discomfort that occasionally leads the traveller to seek medical attention. The psychiatrist Graziella Magherini described, in tourists visiting Florence, acute attacks including disorders of thought and affects, and even including, anxiety attack. She named it the Stendhal syndrome (SS) remembering the experience of the writer when visiting the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence. Methods: We attempt to investigate the incidence of SS or isolated symptoms related to it, in a homogeneous group of travellers. We review other artists who experienced emotion sickness during their trips throughout history. Results: At the end of the III Neurohistory Meeting (Spanish Neurology Society, Italy, February, 2008) a questionnaire was handed out to the participant neurologists, in order to evaluate if during the practical workshops included in the meeting they had experienced symptoms as those described in SS. A total of 48 questionnaires were completed. The mean age was 509 years and the male/female ratio 1.7/1. Twenty-ve percent of the subjects considered they had experienced a partial SS. No panic attacks or thought disorders were identied, but they did suffer artistic effects, mainly in pleasure (83%) and emotion (62%). Conclusions: No SS case was identied among neurologists attending this Neurohistory meeting, but most of them experienced mild disorders of affects and one out of four recognized they have had a partial form of the syndrome. 2010 Sociedad Espaola de Neurologa. Published by Elsevier Espaa, S.L. All rights reserved.

*Corresponding author. E-mail: gueneurol@gmail.com (A.L. Guerrero).

0213-4853X/$ - see front matter 2010 Sociedad Espaola de Neurologa. Published by Elsevier Espaa, S.L. All rights reserved.

350 PALABRAS CLAVE

Sndrome de Stendhal; Fruicin esttica; Neuroesttica; Crisis de pnico; Trastornos del pensamiento; Trastornos de los afectos

A.L. Guerrero et al Sndrome de Stendhal: origen, naturaleza y presentacin en un grupo de neurlogos Resumen Introduccin: El viaje, en su bsqueda de conocimiento y emocin, puede causar malestar psquico que ocasionalmente lleva al viajero a solicitar atencin mdica. La psiquiatra Graziella Magherini describi en turistas que visitaban Florencia un cuadro caracterizado por trastornos del pensamiento, los afectos e incluso crisis de pnico. Lo denomin sndrome de Stendhal (SS) en recuerdo de la experiencia del escritor cuando visit la iglesia de la Santa Croce de Florencia. Mtodos: Investigar la incidencia de SS o sntomas aislados en un grupo homogneo de viajeros. Revisar las experiencias de creadores enfermos de emocin durante sus viajes a lo largo de la historia. Resultados: Al nalizar el III Curso de Neurohistoria de la Sociedad Espaola de Neurologa (SEN) (Italia, febrero de 2008), se entreg a los neurlogos participantes una encuesta para evaluar si durante los talleres prcticos del curso haban experimentado sntomas compatibles con los descritos en el SS. Se cumplimentaron 48 encuestas. Media de edad, 50 9 aos. Proporcin varones/mujeres, 1,7/1. El 25% de los encuestados consider que haba experimentado una forma parcial de SS. No se identicaron crisis de pnico ni alteraciones del pensamiento, pero fue frecuente la inuencia del arte en los afectos, principalmente en el placer (83%) y la emocin (62%). Conclusiones: No hubo ningn caso de SS entre los neurlogos asistentes al III Curso de Neurohistoria de la SEN, pero un signicativo nmero de ellos experiment alteraciones parciales del afecto y uno de cada cuatro reconoci haber presentado una forma parcial del sndrome. 2010 Sociedad Espaola de Neurologa. Publicado por Elsevier Espaa, S.L. Todos los derechos reservados.

Introduction

Psychiatrist Graziella Magherini had the opportunity to study, from the privileged observatory of Santa Maria Nuova Hospital in the centre of Florence, the cases of psychic discomfort aficting patients in her care, usually foreign visitors to this beautiful Italian city. All were brief cases, with an unexpected and acute onset, associated with the visit to a city of art; however, by analysing the biography of each patient in detail, the trip was integrated as a link in a chain of personal events.1 Dr. Magherini distinguished three types of syndrome:1 in 66% of patients, she identied dominant thought disorders; in 29%, dominant affection disorders; and in 5%, panic attacks or somatic projections of anxiety. This study seeks to evaluate the impact of this condition, as well as its symptoms and potential triggering factors, in a homogeneous group of travellers in touch with art objects during a learning trip to Italy.

were no strangers to this syndrome, given that a few days previously and within the theoretical program of the course, Dr. Graziella Magherini had given a lecture about it. The survey was anonymous. After collecting the relevant demographic data, the travellers were asked about their sensitivity to visual arts, their state of mind and their degree of melancholy or anxiety. The survey also inquired about the preparation and pre-trip expectations and the prior level of knowledge about each of the cities visited. Each neurologist was interrogated about the presence of symptoms indicative of SS, either in the form of pleasant sensations (aesthetic pleasure, excitement, euphoria, feeling omnipotent) or negative sensations (changes in perception, feelings of guilt, insecurity or inadequacy, unpleasant somatic symptoms). Finally, all respondents were asked if they thought they had suffered SS or at least a partial form of it. We determined the relationship between having suffered SS and the other variables studied through the 2 test.

Objective

Upon completion of the 3rd Course in Neurohistory of the Spanish Society of Neurology (SEN) (Italy, February 2008), participating neurologists were given a survey. The survey inquired about whether, during the course of the workshops (imparted in the cities of Rome, Florence, Padua and Venice), they had experienced symptoms compatible with those described in Stendhal syndrome (SS). Respondents

Results

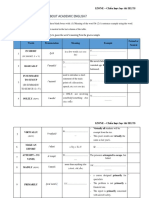

Sixty-four surveys were distributed and 48 (75%) were completed. The averageSD age of respondents was 509 (range, 27-67) years. The male/female ratio among the neurologists was 1.7/1. The states and moods of the subjects are presented in table 1. Between 17 and 13% of respondents confessed to suffering a high degree of melancholy and anxiety, respectively, at

Stendhal syndrome: origin, characteristics and presentation in a group of neurologists

Table 1 States and moods of the subjects studied State of mind Stability Change Uncertainty Mood Tranquillity Restlessness Anxiety Respondents, % 64 14 22 73 21 6

351

Discussion

In describing SS, Dr. Magherini distinguished three types of syndromes:1 in 66% of patients, she identied predominant disorders of thought, within which were included alteration in the perception of sounds or colours, feelings of persecution or guilt and anxiety. In 29% of patients assessed, she observed predominant disorders of affect, so that these individuals associated in varying degrees depressive anxiety, feelings of inferiority and inadequacy, precariousness or feelings of superiority such as euphoria, exaltation, omnipotent thoughts or absence of criticism of their own reality. Finally, 5% of the patients suffered panic attacks or somatic projections of anxiety including chest pain, sweating, dizziness, tachycardia or digestive discomfort. Over 50% of cases in the series presented a psychiatric history. Repressed sexual drives, fatigue, insufcient sleep or the end of the trip were identied as potentially triggering factors, something that also occurred with Stendhal, as will be mentioned later. Some of the patients were living through vital moments of uncertainty or change, but most of those who later presented SS left their homes in a state of psychological well-being. Dr. Magherini sought to determine the possible predisposing factors of SS by comparing demographic and socio-cultural characteristics of patients and other tourists who were not affected. Patients had an older mean age and were less educated. There was a higher percentage of singles, students and unemployed individuals. Among those affected there was a lower percentage of managers, businessmen and freelance professionals than among healthy tourists. Most patients, especially women, were individual tourists (note the gure of single patients) and travelling in a non-organised trip.1 Although it is not easy to compare these results with those presented in our group of neurologists, given the different designs used, the high percentage of respondents (25%) who felt they presented a partial form of SS is striking, as is the frequency of superiority disorders in the affected. Equally notable is the presence, although in a slight degree and in a low percentage of those surveyed, of thought disorders, inferiority alterations and unpleasant somatic symptoms. The difference between the inuence of age on the onset of SS between the Magherini series (age as a predisposing factor) and ours (age as a protective factor) may be resolved in future studies.

Table 2 Distribution of the positive and negative feelings within the sample attributable to the aesthetic experience Sensation Aesthetic pleasure Emotion Euphoria Omnipotent thoughts Slight alterations of perception Slight feeling of guilt Slight sensation of precariousness Slight feeling of inadequacy Slight unpleasant somatic symptoms Respondents, % 83 62 33 8 10 4 4 10 6

the time of travel. Of the respondents, 40% said that the trip had been prepared with readings. As far as prior expectations, 58% of neurologists were seeking to disconnect; 21%, to rest; all the respondents wanted to enjoy; and 96%, to learn. With respect to the pleasant feelings that might fall under a case of SS, 83% of travellers admitted to having experienced signicant aesthetic pleasure; 62%, feelings of excitement; 33%, of euphoria; and 8%, omnipotent thoughts. Within the negative feelings, 10% thought that they had suffered slight alterations in perception; 4%, a certain sense of guilt; 4%, a sensation of precariousness; 10% experienced a slight feeling of inadequacy; and 6% suffered unpleasant somatic symptoms, also to a slight degree. No panic attacks or abnormal thoughts were identied (table 2). Of the respondents, 25% admitted to having presented a partial form of SS. This fact was correlated with having slept poorly during the trip (p=0.035; odds ratio [OR]=3.6; 95% condence interval [CI], from 1.1 to 11.3) and with having felt anxiety previously (p=0.03; OR=5.8; 95% CI, from 1.2 to 27.9). The variables concerning the states and moods that were most related with the presentation of a partial form of SS were the feelings of emotion (p=0.04) and euphoria (p<0.001). The mean age of travellers with a partial form of SS was 44 years, while that of those who claimed not to have suffered it was 52.2 years (p=0.006). According to these data, being over 50 years could be a protective factor against SS.

The trip, the trips

The feelings of pleasure and discomfort associated with discovery have been described in all types of travel throughout history, and change according to the cultural or artistic characteristics of the era in which these trips took place. The traveller/pilgrim of the ancient and medieval world took to the road mainly for religious reasons and travelled by land, but longed to see the sky. The traveller sought relics and shrines and was fascinated, rather than by beauty, by the religious signicance of the monuments or the spiritual benets that the visit offered. Among the few examples we have of this period, the twelfth-century monk

352 Master Gregory, in his Narracio de mirabilibus urbis Romae, tells us how fascinated and dwarfed he felt by the vision of Rome, where there must have necessarily been, according to him, a divine intervention, transforming it into a sort of Civitatis Dei agustiniana.1 Renaissance travellers undertook secular and scholarly trips in search of humanistic sources. The humanist was interested in emotion, but elaborated on it mentally, making it into notion and knowledge. The Renaissance man, therefore, directed his enthusiasm and turned it into culture.1 In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there arose the idea of the romantic journey. Regardless of the object of the visit, the trip was a thrill in itself, a search for pleasure and harmony. Of course, every good emotion could be accompanied by a crisis and all this had to be collected in literary work. The diary therefore appeared. Besides describing places, landscapes and monuments, it reected the authors emotions, who also dwelled on them and, nally, on himself. Thus originated the sentimental journey, using the phrase coined by Laurence Sterne. Italy classical, beautiful, complex and the birthplace of great men is a common denominator in this tourism of the soul. Examples of this new approach are the Italian Journey by Goethe, with its long-awaited process of rapprochement to Rome and, above all, the diaries of trips to Italy written by HenryMarie Beyle, Stendhal. The twentieth century, with the terms tourism and tourist, framed a new individual, who enjoyed a certain degree of prosperity and was emancipated in looking for a personal space in which to enjoy himself. Diaries became guides. Risks did not seem to diminish, as the hustle and the desire for enjoyment and knowledge that accompanied the contemporary journey, not always covered by the necessary pause and reection, could increase the likelihood of psychological discomfort.1 The twenty-rst century only stretches the boundaries without changing the frame; the word tourism becomes associated with other concepts such as adventure, or even spatial.

A.L. Guerrero et al January 1817, in his now famous visit to the Santa Croce (g. 1), the impression of being in the presence of the graves of such great and outstanding men as Aleri, Machiavelli, Galileo and Michelangelo (g. 2), among many others, mixed with the beauty of the Voltairean frescoes, caused him a strong emotion that he described as being close to the place where heavenly sensations reside. When going out into the street, he described the following: a pounding heart, accompanied by the feeling that life had disappeared, walking with a sensation of falling. He therefore looked for a treatment; Stendhal protected himself from these emotions by sitting down and sharing these feelings with a friend, helped by some verses by the poet Foscolo, which described the feelings he had just experienced.1 But Stendhal is not the only traveller to have been fascinated by the various works of art admired in the places visited or by the actual places themselves. The list of creators who fell ill from beauty is endless. Think, for instance, of the painter Paul Gauguin in Tahiti or the fascinating Venice of musicians such as Richard Wagner and Igor Stravinsky, so much in love with this city that they were, at the end of their days, buried there by their own express wish. To delimit what would be a very extensive review, and due to having incorporated in their work not necessarily diaries the semiology of this syndrome of artistic enjoyment of the traveller, we will briey review some experiences of literary creators who fell ill from travel, art, landscape, beauty and emotion. Some of them changed their place of residence for that which aroused such emotions, and they lived and died at the location where they, inevitably, felt they were tied Thus, Lafcadio Hearn, a sort of cursed writer, arrived in Japan in the late nineteenth century, and there he stayed until the end of his life, producing most of his literary work: fantastic, almost terrifying texts and, especially, tales based on Japanese tradition, such as the tender The Boy Who Drew Cats.7 Another similar case is that of the now-forgotten Pearl S. Buck, who lived in early twentieth-century China, as reected in the popular novel East Wind: West Wind.8 The Rafes Hotel in Singapore was witness to the exotic, cosmopolitan life experiences and aesthetics of the writers Somerset Maugham,9 Josef Conrad10 and playwright Nol Coward, who were subsequently joined by Chaplin and Galsworthy. Vzquez Montalbn pays tribute to them in his latest novel, Milenio Carvalho.11 Another example is the path of the Durrell brothers, between Alexandria and the Greek islands, in particular Corfu and Crete, places present in their existences until death. A similar experience is that of Gustav Flaubert and his friends Alfred Le Poittevin and Maxime Du Camp, in their repeated trips to Tunisia, which are reected in the work of Flaubert Salamb12 (the precedent of the historical genre, so popular nowadays). Furthermore, Flaubert himself relates that every time he went to Tunisia he was spared from the seizures that embittered his life, thus attributing antiepileptic therapeutic virtues to this land. Another example in North Africa is the couple formed by Paul and Jane Bowles in Tangier.13 The provocative Bowles was consistent to the end with the city that welcomed him in

Stendhal and other fascinated travellers

Henri-Marie Beyle has been a cultural gure whose signicance has gone beyond his wide-spread, popular nickname: Stendhal. His writing has transcended his personality; the analysis of his gure shows the social fabric of Romantic Europe at the beginning of the nineteenth century, when he lived. He was a politician and a diplomat (in the worldly sense that this label represented at the time), but all that was blurred by the passion he poured into his work as a writer: Stendhal was and remains chemically pure, unbridled and invasive passion.2-6 Focusing on the origin of our story, Stendhal the traveller toured Italy involved in complex emotions. His trip represented a certain initiation because, observing the monuments, he contemplated a part of himself with clarity. Although Florence is the city most gloried in his writings, it was probably Milan that was his favourite city, where he claimed to have felt dead tired, with exhausted organs that had lost their ability to enjoy. When he arrived in Florence in

Stendhal syndrome: origin, characteristics and presentation in a group of neurologists

353

Figure 1

Church of Santa Croce in Florence, anked by the statue of the poet Dante Alighieri.

the difcult moments after the war, when many citizens were wandering around looking for lost roots. Spain has also provoked these passions in renowned scholars. The paradigm is Washington Irving, who always kept Granada present in his native North America.14 Another good example is Gerald Brenan: Don Geraldo, as he was

called in La Alpujarra, a British writer and Hispanist, author of The Spanish Labyrinth,15 who could not bear his nostalgia for Granada at the London nursing home where he was conned. Such was his desire to return that he was repatriated to Spain through the efforts of fans and the national and Andalusian governments. He now rests,

Figure 2

Tomb of Michelangelo in Santa Croce, Florence.

354 together with his wife Gamel Woosley, also a writer, in the Anglican Cemetery of Malaga. Islands are often places of fascination and Spain has several examples, especially in Ibiza and Mallorca. However, the experience of the most famous couple, that formed by George Sand and Frdric Chopin, should be framed within torments. Both had to leave Mallorca, with a very sick Chopin who suffered frequent haemoptoic episodes. George Sand, in her book A Winter in Mallorca,16 reviews with some malice in the form of satirical commentaries that reected the xenophobia of the time, how the locals spent their time being cruel to the couple who were canonically unmarried, to the musician who spat blood, a victim of tuberculosis, and to the writer, a single mother, who walked around the place wearing trousers and smoking from a long pipe. Of those who lived in Mallorca, the most enduring case is that of English writer Robert Graves. His work, essays, ction and poetry, was produced in his retirement at Dei, a wonderful village off the coast of Miramar.17 Graves recognised that the precedent to his discovery of the Majorcan paradise was the reading of Die Balearen, a work by Archduke Luis Salvador who lived most of his life in the palace of Miramar a spot that contains a collection of experiences, observations, routes and customs that may be considered as the best example of the ethnological genre ever written.18

A.L. Guerrero et al

Neuropsychology of art: from psychoanalysis to neuroaesthetics

The rst approach to this problem is offered by psychoanalysis, from which the term artistic enjoyment is proposed. This is also known as a complex of psychological responses generated in an observer by a work of art, with no other interests than the purely artistic. Magherini proposes a model-equation of artistic enjoyment that includes three variables and one constant.19 The rst variable would be the primary aesthetic experience, which would ow, according to the foundations of psychoanalysis, from a primitive mother-child aesthetic experience and which would be established, at least in part, with the personality structure, built with all the interpersonal relationships created from the beginning of life itself. The second variable would be the strangeness, corresponding to the Freudian repressed element, which returns in certain circumstances. The observation of a work of art could thus bring back, under certain circumstances, remote experiences, which could be remembered even without being codied. The third variable would be the selected fact; according to this, there comes a time in the perception of the art object that can largely modulate the reaction generated in the observer. Finally, the constant of this equation would be the artistic value; that is, the art object with its own characteristics, its content or symbolism. The relative importance of these factors in the equation can change for each individual or in the same individual at different times his life.

Figure 3 David by Michelangelo, Galleria dellAccademia in Florence. Source: Magherini G19. Photo by Luciana Majoni, with permission.

In her latest book, Dr. Magherini has changed the focus of her research in response not to patient characteristics as in her rst work,1 but to the constant of the equation of artistic enjoyment; that is, the work of art itself, with all its symbolisms and visual formulas.19 Following this rationale, what better and more characteristic work of art in Florence than David by Michelangelo? (g. 3) David is the spectacular sculptural portrait of a young man expressing the high concentration of physical and emotional energy prior to the transcendental moment of hurling the fatal stone against Goliath, thus symbolizing the civic virtues of heroism, freedom and primacy of intelligence over force. In David we can appreciate a special relationship between movement and posture, between anatomical arrangement and mental attitude, which gives the work an emotional and psychological charge although without losing, especially when contemplating the statue from below, an unexpected sensuality and delicacy, which represent the appearance of a child chosen to free and save his people. Michelangelo crafted this statue, which from the outset his peers considered unique, from a mythical useless block of marble called the giant, on which other artists before him had failed. Its placement was also full of symbolism, as a guardian of the palace where political power resided at the time.20 In her research, Dr. Magherini reviewed entries in the guestbook which the Academy Gallery in Florence made

Stendhal syndrome: origin, characteristics and presentation in a group of neurologists available to visitors during the celebration of the ve hundredth anniversary of the famous sculpture. Many of the travellers noted the anatomical harmony, the perfection, the power of the statue, although some pointed to the imperfection of its proportions. Not a few visitors expressed positive feelings about the work of art, highlighting the movement, the feeling of life in the work; some travellers were fascinated, magnetically attracted, even in love with the statue, despite acknowledging its condition of inanimate object. Finally, some people expressed negative feelings, concerns about the experience, painful emotions; sometimes, the work led to hostility, competitiveness, the desire to be Goliath and correct the course of history, or even to attack the statue.19 During the years after the description of SS, several researchers have observed similar responses in other populations of subjects and locations. Stendhal syndrome has been identied in cities with similar characteristics, such as Venice or Rome, in remote places like India or in locations like Jerusalem, where religious and mystical connotations are joined.19,21 Freud himself, for example, lived a peculiar artistic experience in the Acropolis of Athens, where he felt emotions and memories of his childhood arising. Freud described how the ideas of the Acropolis and classical Greek civilisation were etched in his unconscious during his childhood, and how the vision of the extraordinary monument made him feel enthusiasm initially, and then later a gave him a feeling of alienation and depersonalisation.19 But why do these disorders occur in the presence of a work of art or places of singular aesthetic or spiritual beauty? In 1952, Ernst Kris described how certain issues related to an individuals fantasy life are ubiquitous in the history of art; that is, that often impulses and conicts result in artistic language. A work of art would promote the emergence of feelings that would lead us to recall our personal conicts. Artistic expression, in short, would allow us to evoke emotional intensities that would otherwise not come to light; art provides an opportunity, socially sanctioned and tolerated, of expressing and experiencing intense emotional reactions; the observer moves from an active status to a passive one when recreating the work of art. If the distance between the subject and the object is very small, the emotions are, surely, much more intense.19 The discovery of mirror neurons has brought a new approach to the study of the neurobiological basis of aesthetic enjoyment.22,23 In 1996, it was found in primates that certain neurons in the frontal premotor cortex were activated both when an action was executed as well as when its execution by another individual was observed.24 This empathy is dened as the ability to put oneself in the place of another and has a defensive purpose, as we are informed and prepared for the future actions of those who surround us, actions that are, therefore, the basis of social behaviour.25 Exploring the facilities that empathy provide us, it seems clear that it can be felt when observing a work of art, a fact that had already been observed from the late nineteenth century.19,26 Friedrich Nietzsche envisioned a biological substrate when stating that: empathy with other souls is not moral, but a physiological susceptibility

355

manifested by suggestion.27 Freedberg and Gallese presented a theory of empathic responses to works of art that was not purely introspective, intuitive or metaphysical, but rather had precise and denable materials in the brain. In this form, artistic observation stimulates the mechanisms that mimic and embody emotions, actions or bodily sensations, and these mechanisms are universal because we all have such neurons.28 In this approach to the problem, we also consider historical, social, cultural or personal factors. However, unlike the psychoanalytic approach, the factors are only considered as modulating the artistic perception.28 All the questions aimed at knowing or understanding what art is, present in all human societies throughout history, have failed to obtain satisfactory answers because they have not referred to the brain, the location where art is conceived, executed, received and appreciated.29 The term neuroaesthetics is therefore coined; a concept based on the fact that, just as there is a visual brain that enables an approach to explain artistic creation,30,31 there is also an artistic brain that acts as an extension of the visual brain. Semir Zeki, the originator of this discipline, maintains that all artistic works, both in their conception and in their perception, are expressed in the brain, so that any aesthetic characteristics are necessarily neuroaesthetic. He considers that artists are neurologists who study the visual brain using special techniques, and encourages neurobiologist researchers to take advantage of art as a useful eld in investigating and understanding how the brain works.19,32-34 However, all these researchers and art lovers, despite this proposal of reductionism and no doubt because of it are not able to explain many of the ineffable emotions experienced by those who face beauty in any of its forms.

Conclusions

The data from this work, collected in a single sample of travelling neurologists, modestly complements the limited information currently available about the nature and triggering factors of SS. We have conducted a brief tour on the design of the journey along the history and the experiences of Stendhal himself and of other travellers fascinated by art objects and places of unique beauty. Finally, after approaching the explanations of psychoanalysts, biologists and reductionists of artistic perception, we have tried to arouse the curiosity of the reader. If we know the response of our brains to art, we can better understand its inner workings.

Presentations

Partially presented as a poster at the LX Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology, Barcelona, November 2008.

Conict of interests

The authors declare no conict of interests.

356

A.L. Guerrero et al

16. Sand G. Un hiver Majorque. Palma de Mallorca: Ingrama; 1966. 17. Graves R. Memorias. Palma de Mallorca: Olaeta; 1998. 18. Archiduque Luis Salvador. Die Balearen. Edicin facsmil: Consell de Mallorca; 1996. 19. Magherini G. Ive fallen in love with a statue Beyond the Stendhal syndrome. Firenze: Nicomp; 2007. 20. Zllner F, Thoenes C, Ppper T. Miguel ngel. Obra completa. Taschen; 2008. 21. Bar-El C. The Jerusalem syndrome, Convegno FirenzeGerusalemme: bellezza e storia. Il turismo nelle cita darte. Firenze; 1994. 22. Gallese V, Keysers C, Rizzolatti G. A unifying view of the basis of social cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8:396-403. 23. Gallese V. The shared manifold hypothesis. Journal of Consciousness Studies. 2001;8:33-50. 24. Gallese V, Fadiga I, Fogassi I, Rizzolatti G. Action recognition in the premotor cortex. Brain. 1996;119:593-609. 25. De Vignemont F, Singer T. The empathic brain: how, when and why?. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10:435-41. 26. Koss J. On the limits of empathy. Art Bulletin. 2006;88:139-57. 27. Nietzsche F. En torno a la voluntad de poder. Barcelona: Planeta-De Agostini; 1986. p. 427-8. 28. Freedberg D, Gallese V. Motion, emotion and empathy in esthetic experience. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:197-203. 29. Zeki S. Neural concept formation and art. Dante, Michelangelo, Wagner. Journal of Consciousness Studies. 2002;9:53-76. 30. Livingstone M. Vision and art: the biology of seeing. New York: Abrams; 2002. 31. Kemp M. The science of art. Optical themes in western art from Brunelleschi to Seurat. New Haven and London: Yale University Press; 1996. 32. Zeki S, Lamb M. The neurology of kinetic art. Brain. 1994;117: 607-36. 33. Zeki S. Inner vision. An exploration of art and the brain. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. 34. Onians J. Neuroarthistory. New Haven and London: Yale University Press; 2007.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the organisers and all the attendees of the 3rd Course in Neurohistory of SEN.

References

1. Magherini G. El sndrome de Stendhal. Madrid: Espasa Calpe; 1990. 2. Abry E, Audic C, Crouzet P. Histoire illustre de la littrature franaise. Paris: H. Didier; 1922. p. 551-4. 3. Stendhal. Le rouge et le noir. Le Livre de Poche, Srie Classique. Paris: Librairie Gnrale Franaise; 1972. 4. Ortega y Gasset J. Amor en Stendhal. Estudios sobre el amor. Coleccin Crisol. Edicin especial. Madrid: Editorial Aguilar; 1950. 5. Sebastin Lpez JL. Felicidad y erotismo en la literatura francesa. Barcelona: Icaria; 1992. 6. Stendhal. Recuerdos de egotismo. Madrid: Cabaret Voltaire; 2008. 7. Hearn L. El nio que dibujaba gatos. Madrid: Viento del Sur; 2005. 8. Buck PS. Viento del este, viento del oeste. Coleccin Reno. Barcelona: Editorial Plaza & Jans; 1954. 9. Somerset Maugham W. El lo de la navaja. Mxico: Porra; 1998. 10. Conrad J. El corazn de las tinieblas. Madrid: Alianza; 1992. 11. Vzquez Montalbn M. Milenio Carvalho. Barcelona: Booket; 2004. 12. Flaubert G. Salamb. Le Livre de Poche Classique. Paris: Librairie Gnrale Franaise; 1964. 13. Bowles J. Out in the world. California: Black Sparrow Press; 1995. 14. Irving W. Cuentos de la Alhambra. Coleccin Austral. Buenos Aires: Espasa Calpe; 1947. 15. Brenan G. El laberinto espaol. Paris: Ruedo Ibrico; 1966.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Neuropsychology of EmotionDocument532 pagesThe Neuropsychology of EmotionLarisa Ev-a Elena95% (44)

- Chapter 1: Introduction To Coaching: Confidential Page 1 of 52 5/1/2009Document52 pagesChapter 1: Introduction To Coaching: Confidential Page 1 of 52 5/1/2009James ZacharyPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychiatric Disorders Associated With EpilepsyDocument18 pagesPsychiatric Disorders Associated With EpilepsyAllan DiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Functional Syndrome in NeurologyDocument11 pagesFunctional Syndrome in Neurologyidno1008Pas encore d'évaluation

- CRANE SIGNAL PERSON TRAINING SlidesDocument73 pagesCRANE SIGNAL PERSON TRAINING SlidesAayush Agrawal100% (1)

- Lesson 2 Prepare Cereal and StarchDocument25 pagesLesson 2 Prepare Cereal and StarchLieybeem Vergara50% (2)

- The Investigation and Differential Diagnosis of Asperger Syndrome in AdultsDocument9 pagesThe Investigation and Differential Diagnosis of Asperger Syndrome in AdultsamarillonoexpectaPas encore d'évaluation

- DLM JOY Bread Maker Recipe BookDocument35 pagesDLM JOY Bread Maker Recipe BookmimaPas encore d'évaluation

- Excerpt From Treating Trauma-Related DissociationDocument14 pagesExcerpt From Treating Trauma-Related DissociationNortonMentalHealth100% (3)

- Kosadinos E, Who Is Afraid of Atypical Depression, Dubrovnik 2008Document17 pagesKosadinos E, Who Is Afraid of Atypical Depression, Dubrovnik 2008Emmanuel Manolis KosadinosPas encore d'évaluation

- Somatoform and Other Psychosomatic Disorders: A Dialogue Between Contemporary Psychodynamic Psychotherapy and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy PerspectivesD'EverandSomatoform and Other Psychosomatic Disorders: A Dialogue Between Contemporary Psychodynamic Psychotherapy and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy PerspectivesChristos CharisPas encore d'évaluation

- Toolbox Talk 9: Critical Risks - ExcavationsDocument2 pagesToolbox Talk 9: Critical Risks - ExcavationsPravin GowardunPas encore d'évaluation

- Excerpts From IEEE Standard 510-1983Document3 pagesExcerpts From IEEE Standard 510-1983VitalyPas encore d'évaluation

- Altered States ConsciousnessDocument30 pagesAltered States ConsciousnessNick JudsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Stendhal SyndromeDocument8 pagesStendhal SyndromeGianpiero VincenzoPas encore d'évaluation

- Hazops Should Be Fun - The Stream-Based HazopDocument77 pagesHazops Should Be Fun - The Stream-Based HazopHector Tejeda100% (1)

- 3-PHAP vs. Secretary of Health (Domer)Document5 pages3-PHAP vs. Secretary of Health (Domer)Arnel ManalastasPas encore d'évaluation

- Intellectual Disability and Psychotic Disorders of Adult EpilepsyDocument0 pageIntellectual Disability and Psychotic Disorders of Adult EpilepsyRevathi SelvapandianPas encore d'évaluation

- The Association Between Anomalous Self-E PDFDocument5 pagesThe Association Between Anomalous Self-E PDFferny zabatierraPas encore d'évaluation

- Swinkels PscychopathologieDocument16 pagesSwinkels PscychopathologiesezalwickPas encore d'évaluation

- Suicide Attempts in Hospital-Treated Epilepsy Patients: Radmila Buljan and Ana Marija ŠantićDocument6 pagesSuicide Attempts in Hospital-Treated Epilepsy Patients: Radmila Buljan and Ana Marija Šantićprodaja47Pas encore d'évaluation

- Genetics, Cognition, and Neurobiology of Schizotypal Personality: A Review of The Overlap With SchizophreniaDocument16 pagesGenetics, Cognition, and Neurobiology of Schizotypal Personality: A Review of The Overlap With SchizophreniaDewi NofiantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Asian Journal of Psychiatry: Sureshkumar Ramasamy, Srikala BharathDocument3 pagesAsian Journal of Psychiatry: Sureshkumar Ramasamy, Srikala BharathazedaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Seizure: Vladimir V. Kalinin, Dmitriy A. PolyanskiyDocument4 pagesSeizure: Vladimir V. Kalinin, Dmitriy A. PolyanskiyDuane BrooksPas encore d'évaluation

- Affective Disorders in Cultural Context: Laurence Kirmayer, and Danielle Groleau, PHDDocument14 pagesAffective Disorders in Cultural Context: Laurence Kirmayer, and Danielle Groleau, PHDvarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Epilepsy & Behavior: A B B C D D D D A e A e A e FDocument9 pagesEpilepsy & Behavior: A B B C D D D D A e A e A e FKamel BourasPas encore d'évaluation

- SeizureDocument6 pagesSeizureerikafebriyanarPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 4 - Mental Health Across The Lifespan: Disaster and Mental Health/ Compiled By: Minera Laiza C. AcostaDocument5 pagesLesson 4 - Mental Health Across The Lifespan: Disaster and Mental Health/ Compiled By: Minera Laiza C. AcostaCala WritesPas encore d'évaluation

- Becker 2007Document6 pagesBecker 2007Stroe EmmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Report Session EngDocument22 pagesCase Report Session EngrifkyramadhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Anxiety and Mood Disorders in Narcolepsy: A Case - Control StudyDocument8 pagesAnxiety and Mood Disorders in Narcolepsy: A Case - Control StudyDesyifa Annisa MursalinPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 1007@BF02191557Document10 pages10 1007@BF02191557Sol LakosPas encore d'évaluation

- Adachi Et Al. (2002) - Psychoses and Epilepsy, Are Interictal and Postictal Psychoses Distinct Clinical EntitiesDocument9 pagesAdachi Et Al. (2002) - Psychoses and Epilepsy, Are Interictal and Postictal Psychoses Distinct Clinical Entitieshsanches21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Schizophrenia Revealed To Be 8 Genetically Distinct DisordersDocument3 pagesSchizophrenia Revealed To Be 8 Genetically Distinct DisordersNataliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Schizophr Bull 2011 Simonsen 73 83Document11 pagesSchizophr Bull 2011 Simonsen 73 83Tara WandhitaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Neuropsychology of EmotionDocument532 pagesThe Neuropsychology of EmotionparameswarannirushanPas encore d'évaluation

- Postictal Psychosis, A Cause of Secondary Affective Psychosis: A Clinical Description Study of 77 PatientsDocument19 pagesPostictal Psychosis, A Cause of Secondary Affective Psychosis: A Clinical Description Study of 77 PatientsShadrackPas encore d'évaluation

- Trastornos Neurocognitivos en La EsquizofreniaDocument9 pagesTrastornos Neurocognitivos en La EsquizofreniaMatias Ignacio Ulloa ValdiviaPas encore d'évaluation

- Author 'S Accepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.psym.2016.05.005Document40 pagesAuthor 'S Accepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.psym.2016.05.005jose luisPas encore d'évaluation

- Public Opinions of SchizophreniaDocument53 pagesPublic Opinions of SchizophreniaLaura VaľovskáPas encore d'évaluation

- La Fibromialgia - ¿Un Síndrome Somático Funcional o Una Nueva Conseptualización de La Histeria - AnáliDocument11 pagesLa Fibromialgia - ¿Un Síndrome Somático Funcional o Una Nueva Conseptualización de La Histeria - Análikenny.illanesPas encore d'évaluation

- 2020 Nemeroff - DeP ReviewDocument15 pages2020 Nemeroff - DeP Reviewnermal93Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lehtinen 1994Document4 pagesLehtinen 1994HARINI KPas encore d'évaluation

- Psoriasis, Mental Disorders and Stress: Darko Biljan, Davor Laufer, Pavo Filakovi), Mirna (Itum and Tomo Brataljenovi)Document4 pagesPsoriasis, Mental Disorders and Stress: Darko Biljan, Davor Laufer, Pavo Filakovi), Mirna (Itum and Tomo Brataljenovi)galuh muftiPas encore d'évaluation

- EpilepsieDocument19 pagesEpilepsieFlorin Calin LungPas encore d'évaluation

- JournalDocument11 pagesJournalAdi SyazwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychosurgery, Epilepsy Surgery, or Surgical Psychiatry: The Tangled Web of Epilepsy and Psychiatry As Revealed by Surgical OutcomesDocument2 pagesPsychosurgery, Epilepsy Surgery, or Surgical Psychiatry: The Tangled Web of Epilepsy and Psychiatry As Revealed by Surgical Outcomesximena sanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychiatric Presentations/Manifestations of Medical IllnessesDocument12 pagesPsychiatric Presentations/Manifestations of Medical IllnessesJagdishVankarPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychotic Symptoms As A Continuum Between Normality and PathologyDocument12 pagesPsychotic Symptoms As A Continuum Between Normality and PathologyOana OrosPas encore d'évaluation

- Alexithymia and Chronic Diseases The State of TheDocument7 pagesAlexithymia and Chronic Diseases The State of TheRene GallardoPas encore d'évaluation

- Conversion Disorder: Etiology/ Causal FactorsDocument4 pagesConversion Disorder: Etiology/ Causal FactorsSrishti GaurPas encore d'évaluation

- Handbook of Medical Neuropsychology: Applications of Cognitive NeuroscienceD'EverandHandbook of Medical Neuropsychology: Applications of Cognitive NeurosciencePas encore d'évaluation

- TX. Neurocognitivos EQZDocument10 pagesTX. Neurocognitivos EQZJennie VargasPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychopharmacology in Autism: UKE SAIDocument15 pagesPsychopharmacology in Autism: UKE SAIPablo Antonio AntonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Horowitz 1997Document9 pagesHorowitz 1997Alexandra OanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cognition of Schizophrenic Inpatients and Healthy Individuals: Casual-Comparative StudyDocument6 pagesCognition of Schizophrenic Inpatients and Healthy Individuals: Casual-Comparative StudyAsti DwiningsihPas encore d'évaluation

- Untreated Initial Psychosis: Relation To Cognitive Deficits and Brain Morphology in First-Episode SchizophreniaDocument7 pagesUntreated Initial Psychosis: Relation To Cognitive Deficits and Brain Morphology in First-Episode SchizophreniaelvinegunawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Evaluación de Funciones Cognitivas: Atención y Memoria en Pacientes Con Trastorno de PánicoDocument8 pagesEvaluación de Funciones Cognitivas: Atención y Memoria en Pacientes Con Trastorno de PánicoHazel QuintoPas encore d'évaluation

- Animal Models of Neuropsychiatric DisordersDocument9 pagesAnimal Models of Neuropsychiatric DisordersCarlos Eduardo RodríguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Luria & Zeigarnik - 1977 - On The Use of Psychological Tests in Clinical PracticeDocument12 pagesLuria & Zeigarnik - 1977 - On The Use of Psychological Tests in Clinical PracticeHansel SotoPas encore d'évaluation

- Final EPQDocument19 pagesFinal EPQtanishasen4Pas encore d'évaluation

- 3rd International CongressDocument158 pages3rd International CongressPaladiciuc DanielPas encore d'évaluation

- Neuropsychiatric Sequelae of Nipah Virus Encephalitis: MethodsDocument5 pagesNeuropsychiatric Sequelae of Nipah Virus Encephalitis: MethodsTryas YulithaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 s2.0 S0028393217302877 MainDocument17 pages1 s2.0 S0028393217302877 MainClara Iulia BoncuPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 - Ijaims - Psychiatric Comorbidities in Patients With EpilepsyDocument5 pages2017 - Ijaims - Psychiatric Comorbidities in Patients With EpilepsySantosh KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- HisteriaDocument6 pagesHisteriaAna MoraisPas encore d'évaluation

- A CONCISE REVIEW ON DEPRESSION AND ALTERNATIVE THERAPIESD'EverandA CONCISE REVIEW ON DEPRESSION AND ALTERNATIVE THERAPIESPas encore d'évaluation

- A Beauty 671-680Document29 pagesA Beauty 671-680YollyPas encore d'évaluation

- Estimated Supplies Needed For 6 MonthsDocument2 pagesEstimated Supplies Needed For 6 MonthsShielo Marie CabañeroPas encore d'évaluation

- EffectiveTeaching Full ManualDocument340 pagesEffectiveTeaching Full ManualHabtamu AdimasuPas encore d'évaluation

- Questionnaire For Stress Management in An OrganizationDocument8 pagesQuestionnaire For Stress Management in An OrganizationTapassya Giri33% (3)

- Illiteracy in IndiaDocument11 pagesIlliteracy in Indiaprajapati1983Pas encore d'évaluation

- IZONE Academic WordlistDocument59 pagesIZONE Academic WordlistTrung KiênPas encore d'évaluation

- Mosh RoomDocument21 pagesMosh RoomBrandon DishmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Synopsis - Anu Varghese and Dr. M H Salim, 2015 - Handloom Industry in Kerala A Study of The Problems and ChallengesDocument8 pagesSynopsis - Anu Varghese and Dr. M H Salim, 2015 - Handloom Industry in Kerala A Study of The Problems and ChallengesNandhini IshvariyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Harga Prolanis (Data Dari Apotek Online)Document74 pagesHarga Prolanis (Data Dari Apotek Online)Orin Tri WulanPas encore d'évaluation

- CLC - Good Copy Capstone ProposalDocument6 pagesCLC - Good Copy Capstone Proposalapi-549337583Pas encore d'évaluation

- Recall GuidelinesDocument31 pagesRecall GuidelinesSandy PiccoloPas encore d'évaluation

- Group Activity 1 - BAFF MatrixDocument1 pageGroup Activity 1 - BAFF MatrixGreechiane LongoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- REFERENCES in APA Style 7th EditionDocument2 pagesREFERENCES in APA Style 7th EditionReabels FranciscoPas encore d'évaluation

- 9401-Article Text-17650-1-10-20200718Document5 pages9401-Article Text-17650-1-10-20200718agail balanagPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.3.1 The Autopsy-1Document4 pages1.3.1 The Autopsy-1Alyssa robertsPas encore d'évaluation

- Karakteristik Penderita Mioma Uteri Di Rsup Prof. Dr. R.D. Kandou ManadoDocument6 pagesKarakteristik Penderita Mioma Uteri Di Rsup Prof. Dr. R.D. Kandou ManadoIsma RotinPas encore d'évaluation

- 9 13 23NCM 111 Nursing Research 1 AY 2023 2024Document19 pages9 13 23NCM 111 Nursing Research 1 AY 2023 2024bhazferrer2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Interview Marsha SarverDocument3 pagesInterview Marsha Sarverapi-326930615Pas encore d'évaluation

- Arora 2009Document6 pagesArora 2009ece142Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nursing Skills FairDocument4 pagesNursing Skills Fairstuffednurse100% (1)

- Tinetti Assessment BalanceDocument2 pagesTinetti Assessment Balancesathish Lakshmanan100% (1)