Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Assembling The Team

Transféré par

Walter Jäckisch0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

105 vues51 pagesMost new ventures (rrlore thal1 two-thirds) are started by teams of entrepreneurs woiiing together. A growing number of employees is not necessarily a sign that a new venture is successful. Ssut working with others, like many. Aspects of life, has a "downside"

Description originale:

Titre original

Assembling the Team

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentMost new ventures (rrlore thal1 two-thirds) are started by teams of entrepreneurs woiiing together. A growing number of employees is not necessarily a sign that a new venture is successful. Ssut working with others, like many. Aspects of life, has a "downside"

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

105 vues51 pagesAssembling The Team

Transféré par

Walter JäckischMost new ventures (rrlore thal1 two-thirds) are started by teams of entrepreneurs woiiing together. A growing number of employees is not necessarily a sign that a new venture is successful. Ssut working with others, like many. Aspects of life, has a "downside"

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 51

o 6 jectiv e 5

Ma.c/itz-y- th-iJ e-h-apte-'1-, pou ;h-oulcl !Je u-6/e to:

1 Explain the difference between human capital and

social capital and indicate why the founding team of

new ventures should be high in both.

2 Explain why it is often better for entrepreneurs to

work with cofounders who have different experience,

training, and skills than they do, rather than cofounders

who are similar to themselves in these respects.

3 Describe a new venture's board of directors and

explain how this board can assist the founding team.

Describe other sources of help and guidance for the

founding team; be sure to include boards of advisers,

employees, investors, consultants, and government

programs.

4 Explain why a growing number of employees is not

necessarily a sign that a new venture is successful.

5 Explain why it is useful for cofounders to have clearly

defined roles in their new venture.

6 Define the self-serving bias and explain how it plays

an important role in perceived fairness.

7 Explain the difference between constructive and

destructive criticism.

8 Define stress and describe several techniques

entrepreneurs can use to reduce stress and its

adverse effects.

135

136 PA T l Assembling the Resources

. .

"fwo are better than one; . . . if they fall, the one will lift up his fellow: but woe to him

that is alone when he falleth; for he hath not another to help him up.

. . .

Do you agree? ls there really strength in partnership?

though-the popu_lar view of entrepreneurs suggests

theytend to be "ioners" who prefer to do things in their

. own unique way; the fact is that most new ventures

(rrlore thal1 two-thirds) are started by teams of entrepre-

neurs woii<ing together.

1

This finding is not surprising:

Cooperation and teamwork confer many benefits, often

. helping iridividuals to accomplish tasks they could not

complete alone. ut working with others, like many .

. . . . .

aspects of life, has a "downside" as weil as a potential

"upside;" lt can, irideed, help entrepreneurs to reach

their dreams by combining the talents, energy, and good

judgment of several individuals. But in other cases, it can

prove harmful-especially if the entrepreneurs in question

experience major disagreements or conflict.

2

So, the

question, "Are entrepreneurs better oft founding new

ventures alone or working with cofounders?" has no

simple answer. Rather, the outcomes depend on how

weil founders choose one another and how weil they

then work together.

Here's an example of the upside of having cofound-

ers. ln 1999, two bright, energetic people who had not

previously met were attending a conference on advances

in biotechnology. One was an M.D. who specialized in

treating cardiovascular diseases, while the other had a

Ph.D. in bioengineering and an MBA. When they met,

they quickly realized that they had both been thinking

about starting a biotech company of their own-a

company based ori new techniques for .. developing

effective Within a few short months, they had

formed a close working relationship and decided to

proceed. ln a sense, it was a partnership made in heaven.

The M.D. was a true expert in several diseases, espe

cially ones known as "orphan diseases"-illnesses that

-Hebrew Bible

are fairly rare and, because of this fact, are below the

radar of (arge drug companies, who don't believe it is

worth developing drugs to treat them. The Ph.D. in

bioengineering had expertise in the engineering .and

production aspects of biotechnology, and also, because .

of his business education, had a good understanding of

basic business principles and practices. They soon

formed a company known as Myomatrix-a company that

was so successful that just a few years later, it was

purchased by. a much !arger biotechnology company,

Cytopia, (see Rgure 5.1 ). The two founders of Myomatrix

continue to work together, now as highranking employ-

ees of the larger company. 8oth found the experience of

their collaboration so positive, that they are seriously

considering founding additional companies.

Figure 5.1 A "Dream" Founding Team

When Lawrence Zinsman, M.D., and Shreefal Mehta, Ph.D., MBA,

met, they soon realized that tagether they represented a valuable

array of skills, experience, and training-key ingredients in

founding a successful biotechnology company. They acted on this

belief. and soon founded Myomatrix, a company that made so

much rapid progress, it was soon purchased by a (arger biotech

company.

What does this example of a successful start-up company suggest? To us, the

key task facing entrepreneurs is not in deciding whether to start a new

venture alone or with several other cofounders; as we noted earlier, most

new ventures are actually started by founding teams-several individuals

who work tagether to launch a new venture. Rather, this example suggests

clearly that the key tasks entrepreneurs confront are actually the following:

(1) choosing cofounders wisely and weil, (2) securing the help and guidance

C HA PT ER 5 Assembling the Team: Acquiring and Utilizing Essential Human Capital 137

of others outside the founding tearn who can assist the new venture to attain

its goals (key ernployees, a board of directors, a board of advisers, etc.),

and (3) developing strong working relationships within the founding tearn

and between the founding tearn and other people. In other words, the success

of any new venture is strongly deterrnined by the quality of the human capital

it assernbles-the knowledge, skills, talents, abilities of its cofounders

and ernployees, and also the social capital these individuals possess-their

reputations, social networks, and relationships with others.

3

In this chapter,

we'll focus on issues relating to this key aspect of the entrepreneurial

process.

4

First, we'll exarnine the founding tearn focusing especially on aspects of

their e x ~ e r i e n c e and skills that allow thern to contribute to the new venture' s

success. In this context, we'll consider the question of whether founders

should be sirnilar to one another in background,. training, and knowledge, or

perhaps different. Second, we'Il exarnine the role of people outside the

founding tearn-rnernbers of the new cornpany's board of directors, advisers,

and key ernployees.

Third, we'Il consider the issue of establishing effective working relation-

ships between cofounders and new ernployees. This task requires such

prelirninary steps as establishing a clear division of roles and obligations, plus

careful attention to basic principles of fairness and effective comrnunication.

Good working relations arnong the founding tearn rnernbers and between the

founders and ernployees, the board of directors, advisers, and others provide

an irnportant foundation of any new venture's growth, so assuring that these

exist is a crucial task for entrepreneurs. Finally, we'll consider irnportant ways

'of protecting the new venture's rnost precious human resource--its found-

ers-from the potential ravages of sornething that can put them in serious

danger-extrernely high Ievels of stress. All too often, entrepreneurs seem to

assume that they are indestructible and that their health can absorb virtually

anything without harm. In fact, though, prolonged exposure to high Ievels of

stress can be truly dangeraus to almost anyone, so it's irnportant for

entrepreneurs to be aware of this fact and to take active steps to protect

themselves from its negative effects-not just for their own good, but for that

of their new ventures, too.

The New Venture Team:

Foundation for Success

The founding team of any new venturc is, in a sense, the key human resource

with which it begins. Ultimately, it is the skills, knowledge, energy,

judgment, and creativity of the new venh1re's founders that initiate and

underlie the entire entrepreneurial process. Because this resource is so

precious, it is important that it be as strong as possible. But what, specifically,

does this irnply? Research on the effects of founding teams on the success of

the companies they launch

6

has helped identify several factors that are

especially important-key ingredients in the success of alrnost any new

venture.

One of these factors is the prior experience of the founding tearn. Have they

worked in this industry or rnarket before? Have they ever started or run a

cornpany-in other words, do they have previous entrepreneurial experience?

The greater their relevant experience and knowledge, the rnore likely they

are to launch a successful new venture because they begin with a greater

understanding of the markets they will serve and the challenges they will face.

138 P , R. T l Assembling the Resources

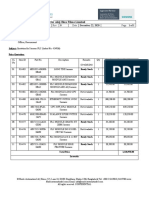

Figure 5.2

Sociaf Networks and

Entrepreneurial Success

Research findings indicate that

the greater the extent to which

entrepreneurs can draw upon social

sources of information (mentors,

informal industiy networks, people

they meet at professional Forums

such as conferences), the more

successful they ute ul rl!wgniLing

opportunities for new ventures.

Having a rrienlor

Having a broad,

i n f o ~ a l industry nelwork -

Parficirating in

conferences and

other professional forums

Source: Based on Ozgen & Baron, see note 8.

So, founding teams should, to the extent this is possible, have appropriate,

relevant experience. Venture capitalists look for such experience and often

require _ it before making an investment.

Similarly, because much of the information entrepreneurs need is

supplied primarily by other. people, another key factor for founders is

having a broad and well-established social network. Countless questions

arise quickly once a new venture is launched. Many of these issues cannot

be readily anticipated. For this reason, having a broad and strong social

network can be tremendously helpful to entrepreneurs, allowing them to

simply pick up the phone to obtain some of the information they want-or

at least, to identify ways of acquiring it. Research Eindings indicate that the

broader entrepreneurs' social networks, and the more they are "connected"

with other people in their field or industry, the more opportunities they

identify and the higher the quality of these opportunities.

7

For instance, in one

recent study, entrepreneurs who had recently founded information tech-

nology companies responded to a survey posted on an Internet site.

8

The

survey obtained information on the extent to which the entrepreneurs

had mentors (experienced individuals who had helped them in their

careers), the extent to Which they had an informal industry-based network

of social contacts that provided them with useful information, and the

extent to which they attended conferences and other professional forums. It

was predicted that the more entrepreneurs reported having-and using-

these three social sources of information, the better they would be at

recognizing opportunities for new ventures. As shown in Figure 5.2, this result is

precisely what was found. These and related findings

9

strongly suggest, to the

extent the members of a founding team of entrepreneurs are well-connected

or networked, the greater the chances that the new venture they launch

will succeed.

Additional factors of considerable importance relate to the specific skills

and characteristics of the founding team members. Every founding team needs

at least one good communicator-one member who can make a strong and

persuasive presentation to customers, venture capitalists, suppliers, and

others. And every founding team needs at least one person who is simply

"good with other people"-someone who possesses a high Ievel of what has

been described as social competence, or the ability to get along well with others

and form effective relationships with them.

10

Aside from these general skills and abilities, it is also useful for founding

team members to have a broad range of knowledge and a wide range of

more specific skills. For instance, as we'll notein a later chapter, someone on

the founding team should know about government programs designed to

assist new companies (see Chapter 4), and someone should have a basic

knowledge of legal and ethical issues relatP.d to dPaling with employees (see

Chapter 12).

Finally, of coursc, thc personal characteristics of founding team m.embers

are important. In this respect, growing evidence indicates that a set of character-

istics known as the Big Five dimensions of personality

are related to success in a wide range of contexts. Here is a

brief description of these dimensions:

1. Conscientiousness. The extent to which individuals

are organized, dependable and persevering rather

than disorganized, unreliable, and easil y

discouraged.

2. Agreeableness. The extent to which individuals

are cooperative, courteous, trusting, and agree-

able versus uncooperative, disagreeable, and

argumentative.

L

[

f

[

r

r

r

r

[

[

[

r

[

[

[

r

f

r

r

f

r

C HA PT ER ::: Assembling the Team: Acquiring and Utilizing Essential Human Capital 139

3. Openness to e:xperience. The extent to which indi-

viduals are creative, curious, and have wide-

ranging interests versus being practical and having

narrow interests.

4. Extraversion. The extent to which individuals are

friendly, sociable, and outgoing rather than

reserved, quiet, and shy.

5. Emotional stability. The extent to which individuals

are anxious, emotional, and insecure versus calm,

self-confident, and secure.

Research indicates that these five dimensions are

very basic ones; in fact, we can frequently teil where

others stand on each of these dimensions, often after

interacting with them for just a few minutes.U But

what do these dimensions have to do with the success

of new ventures? Growing evidence suggests a simple

answer: quite a Iot. For instance, the higher entrepre-

neurs are in conscientiousness (being organized, reliable, and persevering),

the more likely their new ventures are to survive.

12

Other findings indicate

that the higher entrepreneurs are in extraversion, the greater the financial

success of their companies and the Ionger these new ventures survive.

13

Finally, recent findings indicate that entrepreneurs tend to be higher in

conscientiousness, openness to experience, and emotional stability, but lower

in agreeableness, than managers.

14

In short, the personal characteristics of

founding team members do indeed matter and often play a role in the

success of the ventures they create. (Please see Figure 5.3 for an overview of

the factors discussed so far-factors that contribute to the strength of the

founding team and to its likelihood of success.)

ffUinJ:i)'t CUf?itd and 5odat CUf?dat: K:er;- ?Zewwtces

6p- the 7Mvn

Have you noticed an underlying theme in this discussion? If not, here it is,

stated explicitly: the founding team of a new venture serves as its store of

two precious resources: human capital (the new venture's starting "bank-

roll" of skills, knowledge, and abilities) and social capital (the ties founding

members have with others, the benefits they obtain from these relationships,

their reputations, and the social networks they bring to the new venture). In

other words, the founding team (and initial employees) is the source of whal

the new venture knows, and also, in a sense, who it knows. The broadcr and

rkher Ulls soun.:l:! uf bt!llt!r it is .fur the new venture. Existing

evidence indicates-and not surprisingly-that the higher the new venture's

human capital and the higher its social capital, the more likely it is to

succeed.

15

research findfug suggest that the higher the founding team' s social

capital, the more likely it is to discover potentially valuable opportunities and

to develop them.

16

So clearly, human capital and social capital are precious

resources entrepreneurs should seek to mcudmize. And that, in turn, raises a

key question: How should entrepreneurs go about doing this? More specif-

ically, how should they choose cofounders? Common sense offers the

following answer: "Choose partners similar to yourself-you will understand

them and get along with them better." Is this true? We'll now take a closer Iook at

this suggestion and the complex issues it raises in the Qualifying Common Sense

section on the next page.

Figure 5.3

The Founding Team: Some Key

Strengths

T o the extent the founding team

of a new venture possess these

characteristics, it may gain

important advantages in terms

of its future success.

learning 1

objective

Explain the difference

between human capital

and social capital and

indicate why the founding

team of new ventures

should be high in both.

learning

objective

2

Explain why it is often

better for entrepreneurs

to work with cofoun-

ders who have different

experience, training, and

skills than they do, rather

than cofounders who are

similar to themselves in

these respects.

140 Assembling the Resources

Colrtlii?Jh-

_ 7C'tzt/W a61/ut ['nt'l '),enettH -and trhat 'l1l 7Ze - Do 7C'tztJt!J

nlt's usually best to choose partners

similar to yourself .. "

lt is a basic fact of life that people feel most

comfortable with, and tend to like, others who

are similar to themselves in various ways. ln fact,

a !arge body of research evidence points to two

intriguing conclusions regarding the appeal of

similarity: (1) almost any kind of similarity will

do-similarity with respect to attitudes and

values, demographic factors such as age,

gender, occupation, or ethnic background,

shared interests-almost anything; and (2) such

effects are both general and strong. For in-

stance, research shows that similarity influ-

ences the outcomes of employment Interviews

and performance ratings: ln general, the more

similar job applicants are to those who interview

them, the more likely they are to be hired.

Correspondingly, the more similar employ-

ees are to their managers, the higher the

ratings they receive from them.

17

You can

probably guess why similarity is so appeal-

ing: When people are alike on various

dimensions, they are more comfortable in

each other's presence, feel that they know

each other better, and are more confident

that they will be able to predict each others'

future reactions and behavior. ln short, every-

thing else being equal, we tend to associate

with, choose as friends or cofounders, and

even marry people who are similar to ourselves

in many respects.

Entrepreneurs are definitely no exception

to this similarity-leads-to-liking rufe. ln fact,

most tend to select people whosc back-

ground, training, and experience are highly

similar to their own. This is far from surprising:

people from similar backgrounds "speak the

same language"-they can converse more

readily and smoothly than individuals from

distinctly different backgrounds; and often,

they already know one another because they

have attended the same schools or worked

for the same companies. The Overall result is

that many new ventures are started by teams

of entrepreneurs from the same fields or occu-

pations: Engineers tend to work with engineers;

entrepreneurs with a marketing or sales back-

gmund tend to work with others from these fields;

scientists tend to work with other scientists, and

so on (see Figure 5.4).

ln one sense, this tendency is an important

"plus": As we'll notein a later section, effective

communication is a key ingredient in good

working relations. So the fact that "birds of a

feather tend to flock together" in starting new

ventures offers obvious advantages. Further,

recent findings

16

indicate that in new ventures-

and especially ones that are truly doing some-

thing new and innovative-similarity between

team members can contribute to successful

performance.

On the debit side of the ledger, however,

the tendency for entrepreneurs to choose

Figure 5.4

Similarity in Founding Teams of Entrepreneurs

Because people find it more pleasant and comfortable

to work with others who are simi/ar to themse/ves,

teams of entrepreneurs often consist of individuals

with similar background, training, and experience.

This can be detrimental to the success of the new

ventures they found.

L

l

[

r

r

r

r

r

[

[

r

n

D

n

C HA f' TE R 5 Assembling the Team: Acquiririg and Utilizing Essential Human Capital 141

cofounders whose background and training are

highly similar to their own has several serious

drawbacks. The most important of these cen-

tersaraund redundancy: themore similar

people are, the greater the degree to which their

knowledge, training, skills, and aptitudes overlap.

For instance, consider a group of engineers who

start a company to develop a new product. All

have technical expertise, and this is extremely

useful in terms of designing a product that

actually works. But because they are all engi-

neers, they have little knowledge about market-

ing, legal matters, or regulations concerning

. employees' health and safety. Further, they may

know little about writing an effective business

plan which, as we'll see in Chapter 7, is offen

crucial for obtaining essential financial resources

and determining how to operate a company

effectively. Moreover, although all of them have

excellent quantitative skills, they are not proficient

at preparing written documents or in "selling"

their ideas; as is offen the case with individuals

from a or scientific background, they

are better with numbers than words. Further,

because all were trained in the same field (and

may even have studied at the same school), they

have overlapping social networks: They tend to

know the same people, and hence have a limited

range of contacts from whom they can obtain

needed resources-information, financial sup-

port, and so on.

ln contrast, recall Myomatrix, the biotech

start-up described in the opening to this chap-

ter. The cofounders came from different fields-

a branch of engineering and medicine. Also,

they had different career experience: One had

run a medical practice while the other had an

MBA and considerable business experience. So

afthough they shared an interest in biotechn.ol-

ogy, they came to it from different directions and

with different skills and knowfedge. The resuft

was a strong founding tearn that contributed in

many important ways to the new veriture's

success.

By now the main point shoufd be clear:

What any team of entrepreneurs needs fr

success is a wide range of inforrnation, skilis,

aptitudes, and abilities. And this variety is less

fikely to be present when all members of the

foundihg team are highly similar to one another in

important ways. ldeally, what one team member

Iacks one or more others can provide so that, as

the quotation affered at the start of this chapter

suggests, the whole is indeed greater than the

sum of its parts because the team can pool its

knowledge and expertise. Rule number one for

entrepreneurs in assembling their founding

teams, then, is the following:

Don 't yield to the temptation to work

solely with people whose background,

training, and experience are highly sim-

ilar to your own. Doing so will be easy

and pleasant in many ways, but it may

faif to provide the rich array of human

resources the new venture needs. Over-

all, it may often be better to choose

cofounders on the basis of complemen-

tarity-people who can provide what you

don't have, and vice versa.

142 f' '' f , ,. Assembling the Resources

learning 3

objective .

Describe a new venture's

board of directors and explain

how this board can a.ssist the

founding team. Describe other

sources of help and guidance

for the founding team; be sure

to include boards of.advisers,

employees, investors, consultants,

and government programs.

Beyond the Faunding Team:

Board of Directors, Key Employees,

Advisers

The founding team plays a crucial role in the launch of any new venture-how

could it be otherwise? But although it is important, the founding team is not

the entire story. Almost all new \'entures-and especially successful ones-

"import" \'aluable human resources that supplement those provided by the

founding team. Although these resources come from many different sources,

three of the most important are the board of directors, key employees, and

advisors and consultants. Savvy entrepreneurs draw on these added sources

of knowledge, expertise, and skills and use them to boost their companies into

the fast-growth pattern they seek.

13tJa'zd tJif

Any new venture that begins as a corporation (see Chapter 8 for a discussion

of the legal forms new companies can take) is required by law in many

countries to choose a board of directors-a group of individuals who are

elected by the shareholders in the corporation and have the task of overseeing

the management of the company. Although the duties of such boards vary

(e.g., they appoint officers of the corporation, declare dividends, provide

financial oversight), their main contribution, from the point of entrepreneurs,

is to provide advice and guidance. Wise entrepreneurs choose as board

members individuals who are knowledgeable and experienced in areas

relevant to thenew venture's operations. For instance, returning once again to

Myomatrix, the start-up biotech company, the founders chose for their board

of directors individuals \ovith a rich store of experience in the biotech field-for

instance, the CEO of a much !arger company. Other members of the board

held important positions in local banks or sei1ior positions in nearby

universities. The result? The board of directors could-and did-provide the

founding team with important advice and guidance, input that helped them

make their new venture a success.

In addition, because these well-respected individuals agreed to serve on

the board, Myomatrix gained something eise, too: lt gained reputation and a

sense of legitimacy. After all, why would such prominent people agree tobe

on the board of directors of a small unknown company unless they feit that it

had a promising future? Venture capitalists and other potential investors

certainly reached this conclusion, and the presence of these individuals on

Myomatrix's board helped it to gain the attention of the company that

ultimately purchased the young start-up.

Clearly, then, choosing an excellent board of directors is an important way

for new ventures to leverage their human capital-to add to the skills and

knowledge provided by the founding team in \vays that increase the chances

of success.

New ventures face serious obstacles \Vith respect to attracting outstanding

employees. As new companies, they are relatively unknown to potential

employees and cannot offer the legitimacy or security of established fim1s. Thus,

they enter the market for human resources with important disadvantages. Hmv

do start-up companies overcome these difficulties? Largely through the use of

social networks. In other words, they tend to hire people they know either

directly, from personal contact, or indirectly, through recommendations from

L

l

(

r

r

r

r

r

[

[

[

r

[

n

(HA PT ER S Assembling the Team: Acquiring and Utilizing Essential Human Capital 143.

people they do know and trust

19

(see Figure 5.5). This makes a Iot

of sense because unlike larger, established companies, start-up

ventures cannot readily train employees themselves; as a result,

they must obtain them from outside the new firm, and this they

usually accomplish by using their existing networks.Z

0

By hiring people they knw (often, family members, friends,

or individuals with whom they went to school or worked in the

past), entrepreneurs are able to acquire human resources quickly,

without the necessity for lang and costly searches. Second,

because they know the people they hire either directly or

indirectly, entrepreneurs can more easily convince these individ-

uals of the value of the opportunity they are pursuing. Third, new

ventures often lack clearly established rules or a well-defined

culture; having direct or indirect ties with new employees

simplifies the task of integrating them into this somewhat loose

and changing structure.

One important reason for hiring people entrepreneurs

already know, directly or indirectly, is that serious errors in

hiring can be devastating for new ventures. Start-up companies

generally have limited resources, and making a bad decision

wastes these limited assets. Moreover, firing employees who

don't work out is always difficult and raises complex legal issues.

This aspect is certainly one reason why entrepreneurs often prefer

to use their social networks for hires, at least initially.

One exception to this general rule occurs when new ventures grow !arge

enough to require highly experienced management, such as an experienced

CEO or CFO. Recruiting such people is difficult even for !arge companies, and

small ones face an even tougher task in this respect. For this reason, some

entrepreneurs turn to executive search firms that specialize in identifying and

recruiting top-level people. This approach is generally expensive, so it rarely

occurs until start-ups are no Ionger struggling to survive; rather, search firms

are more typically employed after the new venture has become profitable and

when it is growing rapidly.

How should entrepreneurs go about the tasks of recruiting, motivating,

and ultimately retaining excellent employees? We'll cover these topics in

Chapter 12, so here we merely call your attention to the importance of these

tasks that must be carried out successfully if a new venture is to flourish. We

should also mention, however, that a highly skilled workforce is especially

important to new ventures operating in highly dynamic (i.e., rapidly

changing) environments. In contrast, companies operating in more stable

environments or industries can benefit greatly from helping their ernployees

arquire the skills and knowledge they need. In other words, the human

resources practices new ventures adopt should-and often do-reflect thc

kind of industries in which they operateY

Two other issues relating to hiring employees are important and worthy of

mention: Is bigger always better? In other words, is a growing workforce

always a good sign that a new venture is succeeding? And should new

ventures hire temporary or permanent employees? We'll now consider both of

these questions briefly.

ls Bigger Always Better? Number of Employees As a Factor

in New Venture Growth

New ventures face many difficult questions as they grow and develop,

but among these, orte of the most complex concerns the number of ernployees

they should hire. Adding employees-expanding the new venture's human

resources-offers obvious advantages. New employees are a source of

information, skills, and energy; further, the more employees a new venture

Figure 5.5

Social Networks: A Major Source

of New Employees for New

Ventures

Entrepreneurs often rely on social

networks as a source of new

employees. The individua/s they

hire are anes they know or ones

recommended to them by people

they trust.

learning 4

objective

Explain why a growing

number of employees is

not necessarily a sign

that a new venture is

successful.

.,

..

a

..

.

~

~

c

0

;;;

>

144 PA R T 2 Assembling the Resources

has, the greater the number and !arger the size of the projects it can undertake.

As we noted earlier, there is little doubt that in many contexts, people working

tagether in a coordinated manner can accomplish far more than individuals

working alone. But adding employees to a new venture has an obvious

downside, too. Employees add to the new venture' s fixed expenses and raise

many complex issues relating to the health and safety of such individuals-

issues that must be carefully considered. In a sense, therefore, expanding t h ~

company' s workforce is a two-edged sword and the results of expanding the

nurnber of employees can truly be rnixed in nature.

Overall, however, existing evidence suggests that on balance, the benefits

of increasing the nurnber of employees outweigh the costs. New ventures that

_ start with more employees have a greater chance of surviving than ones that

begin with a smaller number.

22

Similarly, companies with more employees

have higher rates of growth.than ones with fewer employees.

23

Profitability,

too, is positively related to the size of new ventures. For example, the greater

the nurnber of employees, the !arger the earnings of new ventures, and the

greater the income generated by them for their founders.

24

We should quickly note that these findings are all correlational in nature:

They indicate that number of employees is related in a positive rnanner to

several measures of new ventures' success. They do not, however, indicate

that hiring new employees causes such success. In fact, both nurnber of

employees and various measures of financial success may stern from other,

underlying factors, such as the quality of the opportunity being developed,

commitrnent and talent of the founding team, and even general economic

conditions (it is often easier to hire good employees at reasonable cost when

the economy is weak than when it is strong). So the relationship between new

venture size (number of employees) and new venture success should be

approached with a degree- of caution. Still, it seerns clear that to the extent

human resources are a key ingredient in the success of start-up cornpanies, the

!arger their workforce, the greater their success is likely to be.

Temporary or Permanent Employees? Commitment Versus Cost

Achieving an appropriate balance between costs and numbers of new

employees is not the only issue facing new ventures where expanding their

workforces is concerned. In addition, they must determine whether new

employees should be hired on a temporary or permanent basis. Again, both

strategies offer advantages and disadvantages. Temporary employees reduce

fixed costs and provide for a great deal of flexibility; they can be hired and

released as the fortunes of the venture dictate. Further, hiring temporary

employees perrnits the new venture to secure specialized knowledge or skills

that may be required for a spedfic project. When the project is completed, the

temporary employees depart, thus reducing costs.

On the other hand, there are several ciisadvantages associated with

ternporary employees. First, they may Iack the commitrnent and motivation of

permanent employees. After all, they know that they have been hired on a

contract basis for a specified period of time (although this contract can often be

extended), so they have little feeling of commitrnent to the new venture: In a

sense, they are visitors, not permanent residents. Companies also face the real

risk that temporary employees will acquire valuable knowledge about the

company or its opportunity and then carry this information to potential

competitors. Permanent employees, in contrast, tend to be more strongly

- committed and motivated with respect to the new venture, and are less likely

to leave-especially if they gain an equity stake in the company. _

Overall, then, the choice between temporary and permanent employees is

a difficult one. Which is preferable seems to depend, to a !arge extent, on

specific conditions faced by a new venture, such as the industry in which it

operates or the opportunity it is attempting to exploit. In situations where

[

[

r

r

r

r

r

[

[

[

r

r

[j

0

r

l

,

'

C HA P' T F.. R 5 Assembling the Team: Acquiring and Utilizing Essential Human Capital 145

flexibility and speed of acquiring new sets of knowl-

edge and expertise are crucial (e.g., arnong software

start-up companies), temporary employees may be

beneficial.

25

In situations where employee commit-

ment and retention are more important (e.g., employ-

ees rapidly acquire skills and knowledge that increase

their value to the new venture), then focusing on a

permanent workforce may be preferable.

26

tJj acmiJ&v>-

Corporations are required to have boards of directors,

but no company is required to have a board of

advisers-a group of experts who are invited by a

company's managers to provide advice and input on a

regular basis (see Figure 5.6). Although not a legal

requirement, appointing a board of advisers is increas-

ingly popular among entrepreneurs. Why? Because doing so allows the new

venture and its founding tearn to draw upon the expertise and knowledge of

experienced individuals. Additionally, many experienced and prominent

people are more willing to serve in this relatively informal role than in the

more formal one specified by being on a board of directors.

Entrepreneurs interact with boards of advisers in different ways, but

typically, they rneet with thern several times a year to seek their advice and

guidance. Face-to-face rneetings are not always necessary; teleconferencing or

Internet connections can sometimes be sufficient. However they contact their

ad visers, the basic principle for entrepreneurs rernains the same: Choose

people for this role who can really help. In other words, select ones who have

experience in the industry or rnarket where the new venture operates, who

have specific skills the founding team Iacks, and who are well-respected in

their various cornmunities. How can new ventures attract the help of such

individuals? Generally, not by paying them in cash; the financial resources of

new ventures are usually too limited for this, and potential advisory board

rnernbers would often be very expensive if they were recruited in this manner.

Instead, such people agree to serve as advisers because they have intrinsic

interest in the business of the new cornpany, andin return for alternate forms

of compensation, such as shares in the new venture. However they are

recruited, their help can be invaluable and wise entrepreneurswill generally

seek it out.

atzet

In addition to help from a board of directors and a board of advisers,

entrepreneurs can also often benefit from input provided by several other

sources. First, of course, investors have a real stake in the start-up ventures

they finance: They want thern to succeed and are often willing to provide

advice, assist in hiring key ernployees, and assist entrepreneurs in rnaking

key business contacts. This is hardly surprising; After putting their money

fnto a new venture, investors often rnonitor it closely and require detailed

reports from the entrepreneurs. This often Ieads thern to recognize when

things are not going well, and to intervene in various ways to irnprove the

situation.

In addition, entrepreneurs can sornetirnes obtain help from consultants,

experts in various fields or areas whorn they hire for specific fees. For

instance, rather than hire their own accountants, entrepreneurs often prefer

to hire such help as needed. Similarly, they hire specia1ists in production or

engineering to help solve problerns relating to these areas. The same may

Figure 5.6

Boards of Advisers: Help from

the Experts

A growing number of new ventures

are appointing boards of advisers-

groups of peop/e with skil/s, knowl-

edge, and experience relevant to

the company's business. New ven-

tures are not /egally required to

appoint such boards, but many

entrepreneurs recognize their value

and are estab/ishing them in order

to benefit from the help these

boards can provide.

146

&,qrd of b l ~ o r s .

Board of:-A(kjsers

Einployt$

C6nsvltanfs

Investors

GOvetnment--

Programs

Figure 5.7

Assembling the Resources

even be true for marketing, at least initially. Consultants

aren't inexpensive, but if their services ultimately help a

new venture avoid making costly mistakes, it is capital

weil invested.

We should also note that consultants are some-

times provided through government programs and

agencies. For instance, SCORE, one such agency, has

volunteers-typically retired entrepreneurs or execu-

tives-who enjoy helping nev.r companies. Their

services are generally free, and they can be especially

helpful to entrepreneurs when hiring specialized

employees v.rould not be feasible.

In sum, as shown in Figure 5.7, entrepreneurs are

definitely not alone: They can obtain help from -a

number of sources, if they are wise enough to seek it.

Help ls Out There lf You Ask

for lt

No one-not even the most talented and experienced founding team-has all

the knowledge and skills needed to run a successful and rapidly growing new

venture. So clearly, entrepreneurs should seek help and put it to use in

developing the opportunities they have chosen to pursue. (Choosing

cofounders whose background and experience is heterogeneaus offers many

advantages, but it involves certain risks, too. Piease see the Danger! Fitfall

Ahead! section below for an explanation.)

Entrepreneurs can obtain he/p in

running their new ventures from

many different sources. Some of

the most important ones are

summarized here.

The Risks of Choosing Cofounders

You Don't Know-And How to

Reduce Them

Earlier, we recommended that in building their

founding teams, entrepreneurs should try to

avoid "cloning" themselves-working with

people who have the same mix of knowledge,

skills, training, and characteristics as they do.

The main reason for this recommendation is

clear: The founding team provides the basic

store of human capital on which the new

venture can draw, so the broader and more

diverse this supply of valuable resources, the

better. But there is another side to this issue,

one we don't want to overlook. This has to do

with the problems involved in working with

other people we don't know weil. Since we

don't have past experience with them, we have

to guess about what they actually bring to the

table. Do they have the skills and knowledge

they claim to have? Have they had the expe-

rience they describe to us? And what are they

like as individuals-is our first impression of

them accurate along key dimensions such as

their Ievel of conscientiousness (reliability,

dependability), extraversion (are they really

outgoing and friendly-or not?), and so on.

Obviously, it's important for entrepreneurs to

make accurate judgments in these respects,

because once the new venture is launched, it

is often very difficult to dissolve the business

relationships that have been formed without

damaging the company itself. So, a key ques-

tion arises: How can we assess other people

accurately? This topic has received decades of

attention in other fields (e.g., psychology), and

much has been learned about how it proceeds

and about how we can be more accurate at it.

Here, we'll simply offer a few generat pointers

!hat can help entrepreneurs make the correct

decisions.

1. Always check credentials-especially

crucial ones: lt doesn't mean that when

considering someone as a potential part-

ner you should hire a private investigator-

far from it. Rather, it simply means that a

few well-placed phone calls can readily

confirm information a potential partner is

L

[

r

f

r

f

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

[

[

r

L

r

l

l

r

r

CHAPTER 5

Assembling the Team: Acquiring and Utilizing Essential Human Capital 147

: .. -- .

. /

.. ,

__ .-

tion,- or dapartures -fromtruthfulncnn,

.. through to nonverbal cues-

expressions, body or

. rionverbai as-

pects'(?fspee.ch {hotrelated to the

-__ . '6hne Wtirds theyspeak..::for

... -- the tne of people

- - ; shbw -

. . '' .-

.. verbal for instancei fadal

are one chanhel, body. moveO,enti -

another.). These are be

qil:sic

.lm=<:l<>.rl'!<:l

. : . .

ofteri frequeritly revealed by certain

of eye .cnfact. People \fo/h are lying. often -.

blink ften and -show pupils that

mre dil?ted thari someone. who is telfing

. trth:: They rrtay also an unusually

_low leyel of eye contact or-surprisingly-.--an

\1nuiualiy high one, as they aftempt fo fake

being:honest by looking others right ir:r

-tt\eeye.

(contiriued)

148 PART l Assembling the Resources

... : _ ...

..:

-7-

. ..:.'

. ;,.:- ',.. ,.:-... . : ."' .

. .. :.

Figure 5.8 Recognizing Deception

By paying careful attention to the cues summarized here, it is

often possib/e to tel/ when others are not being entirely

truthful with us.

.---.. .. .. :<::. , .. -

'. _... :.-.-->:.: __. :--;'_:_. ....

Utilizing the New Venture's

Human Resaurces: Building Strang

Warking Relatianships Amang

the Faunding Team

Assembling the resources needed to perform a task is an essential first step;

indeed, there is no sense in starting unless the required resources are available

or easily obtained as the need arises. But gathering resources is only the

beginning; the task itself rnust then be performed. The same principle holds

L

f

r

r

r

r

r

[

r

r

r

r

[

u

n

11

n

I

r

C HA PT ER 5 Assembling the Team: Acquiring and Utilizing Essential Human Capital 149

true for new ventures: Assembling the necessary human capital-an

appropriate pool of knowledge, experience, skills, and abilities-is only

the beginning. The people who constitute the founding team must then

work tagether in an effective manner if the new venture is to succeed.

Unfortunately, this key point is often overlooked or given insufficient

attention by entrepreneurs. They are so focused on the opportunity they

identified and hope to develop that they pay scant attention to building

strong working relationships with one another-working relationships that

help the new venture to utilize its human capital to the fullest. Growing

evidence suggests that such relationships are an essential ingredient in new

ventures' success.

27

For instance, in one recent study of 70 new ventures,

higher Ievels of cohesion among thefounding team (positive feelings toward

one another) were stron&ly associated with superior financial performance

by these new ventures.Z In view of such evidence, a key question arises:

How can strong working relationships between founding team members be

encouraged? Although this question has no simple answer, three factors

appear to play a crucial role: a clear initial assignment of roles (responsibilities

and authority) for all founders and other team members; careful attention

to the basic issue of perceived fairness; and developing effective patterns

and styles of communication (especially with resped to feedback) among

team members.

A major source of conflict in many organizations is uncertainty concerning two

issues: responsibility and jurisdiction. Disagreements-sometimes harsh and

angry ones---often develop over the question of who is supposed to be

accountable for what (responsibility), and over the question of who has the

authority to make decisions and choose among alternative courses of action

(jurisdictlon).Z

9

One effective way of avoiding such problems is through a clear

definition of roles-the set of behaviors or actions that individuals occupying

specific positions within a group are expected to perform, and the authority or

jurisdiction they will wield. Once established, clear roles can be very useful.

For instance, consider once again the successful biotech company we

described earlier-Myomatrix. (We continue to refer to this company because

it illustrates so many principles we believe to be important.) The cofounders

had an almost perfect mix of skills and experience---one was an M.D. and the

other held a Ph.D. and an MBA. Seeking to build on this key advantage, they

negotiated clear and distinct roles for each to play. The physician ran the

laboratory and set the direction for many of the company's research projects;

after all, he had detailed knowledge of the diseases for which Myomatrix was

seeking new drugs and treatments. The other founder, in contrast, handled

many of the business-related aspects of the company-everything from

maintaining required records through seenring new capital. Both contributed

to the scientific and research activities of Myomatrix. Because these roles

were discussed arid arranged even before the company was launched, the

cofounders could truly work in a complementary manner, with each providing

valuable contributions for the company. This, we suggest, was one ingredient

in Myomatrix's success.

The lesson is clear: Once the founding team has come tagether to form the

new venture, its members should. divide key responsibilities and authority

between them in accordance with each founder' s expertise and knowledge.

Anything eise may weil prove costly and detract from the new venture's

success. This sounds very simple, but the factisthat many entrepreneurs are

highly energetic, capable people, used to "running the show'' in their own

lives. Unless they can learn to coordinate with their cofounders, though, they

may run the risk of seriously weakening their own companies.

learning 5

objective

Explain why it is useful

for 6ofounders to have

clearly defined roles in

their new venture.

150 ? ART 2. Assembling the Resources

learning

objective

6

Define the self-se_rving bias and

explain how it plays an impor-

tant role in perceived fairness.

A Note on Role Conflict

AB we just stated, it is important for entrepreneurs to establish clear-cut roles

for all cofounders in order to facilitate coordination between them and to

maximize the value of the new venture's human capital. But entrepreneurs,

like everyone eise, have roles outside their companies as well as within them.

For instance, they may be spouses, significant others, or parents; and they are

certainly sons and daughters to their own parent:S. A dassie finding in the field

of human resource management is that the roles all of us hold sometimes make

incompatible demands upon us. In other words, we experience role conflict-

contrasting expectations about behavior and responsibilities held by different

groups of individuals.

30

Spouses and significant others, for example, expect us to

be areund to fill their emotional needs at least some of the time; similarly, children

have legitimate expectations for their parents. So dealing with role conflict can be a

stressful task-and a difficult juggling act-for entrepreneurs who must devote so

much of their time to running their new ventures. Role conflict can be a serious

matter with important consequences; if the significant people in entrepreneurs'

lives cannot come to terms with the heavy demands on the entrepreneurs' time

and energies, serious interpersonal problems can result. These issues, in turn, can

add to entrepreneurs' stress and reduce their overall performance. Clearly, then,

getting one's spouse, significant others, children, and other family members "on

board" is a task no entrepreneur can afford to overlook.

P&tceived 'FaPzM5-5-: an ~ l u w e l3ut 85&liid

CtJtnpotWd

Try this simple exercise: Think back over your life and remernher a specific

occasion when you worked with others on some project. The context is

unimportant-it can be any kind of project you wish-but try to recall an

incident in which the outcome was positive and the project was a success.

Now, divide 100 points between yourself and your partners according to how

!arge a contribution each person made to the project. Next comes the key

question: How did you divide the points? If you are like most people, you

probably gave yourself more points than your partners. (For example, if you

had one partner, you took more than SO points; if you had three, you took

more than 33.3 points, and so on.)

Now, by way of contrast, try to recall another incident-one in which you

also worked with partners, but in which the outcome was negative and the

project failed. Once again divide 100 points between yourself and your partners

according to how large a contribution each person made to the project and its

outcome. In this case, you may weil have given others more points than yourself;

in other words, you held them, not yourself, responsible for the negative results.

If you showed this pattern, wekome to the dub: You are demonstrating a

powerful human tendency known as the self-serving bias. This is the tendency to

attribute successful outcomes largely to internal causes (our own efforts, talents,

or abilities) but unsuccessful ones Iargely to external causes (e.g., the failings or

negligence of others, factors beyend our control).

31

This bias has been found to

be a strong one, with serious implications for any situation in which people

work together to achieve important goals. Specifically, it often Ieads all those

involved to conclu.de that somehow they have not been treated fairly. Why?

Because each participant in the relationship tends to emphasize her or his own

contributions and minimize the contributions of others, so they conclude that

they are receiving less of the available rewards than is justified. Further,

because each person has the same perception, the result is often friction and

conflict between the individuals involved.

In other words, this tendency raises complex questions relating to

perceived fairness-a key issue for entrepreneurs. Because of the self-serving

f

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

lf

'r

r

I r

I

lf1

I

I

i r l '

I .

I r

r

I f

r

CHArTER 5 Assembling the Team: Acquiring and Utilizing Essential Human Capital 151

.:,:

Figure 5.9 The Self-Serving Bias and Perceived Unfaimess

Because most individuals have a strong tendency to perceive their contributions to any i:han they are, they also

tend to perceive that theyare receiving a smatler share of available rewards than is appropriate. tn oiher words, they conclude that they

are being treated unfair/y. This can be a serious problern for founding teams of entrepreneurs.

bias (plus other factors, too), we all have a tendency to assume that we are

receiving less than we deserve in alrnost any situatin. In other words, we

perceive that the balance between what we contribute and what we receive is ,

less favorable than it is for other persons. In specific terrns, we perceive that

the ratio between what we are receivin.g and what we are contributing is srnaller

than that for others. In general, we prefer that this ratio follow the general

principle of distributive justice (also known as equity), which suggests that the

larger any person's contributions, the larger her or his rewards. Most people

accept this principle as valid, but the self-serving bias Ieads us to cognitively

inflate our own contributions-and hence to conclude that in fact, we are not

being treated fairly (see Figure 5.9).

What do people do when they perceive that the distribution of rewards is

unfair? Generally, they react in a variety of ways, none of which are benefidal to a

new venture. The rnost obvious tactlc is to dernand a larger share; but if others do

not view these demands as legitirnate, conflict is the likely outcorne. Another

approach is to reduce one's contributions-to reduce effort or shirk responsibility.

This, too, can be very harmful to the success of a new venture. An even rnore

darnaging reaction is to withdraw-either physically or psychologically. Dis-

aifeeted cofounders sometirnes pull out of new ventures, taking their experience,

knowledge, and skills with them. If they are essential mernbers of the team, their

departure can mark the beginning of the end for the ventures in question.

All these possibilities are bad enough, but even worse is the fact that

people tend to focus relatively little attention on the issue of fairness when

things are going weil (e.g., they are getting along weil with their cofounders),

but they devote increasing attention to this issue when things begin to go

badly.

32

In short, when a new venture is succeeding and reaching its goals,

members of the founding team rnay show little concem over distributive justice.

If things go badly, however, they begin to focus increasing attention on this

issue-thus intensifying this source of interpersonal friction.

Given the existence of this cycle, it is truly crucial for the founding teams

of new ventures to consider the issue of perceived faimess very carefully. This

iinplies that they should discuss this issue regularly to assure that as roles,

responsibilities, and contributions to the new venture change (which they will

inevitably do over time), adjustments are made with respect to equity, status,

and other rewards in order to reflect these changes. This is a difficult task since

all members will tend to accentuate their own contributions (recall the powerful

self-serving bias). But since the alternative is the very real risk of tension and

conflict between the fotmding tearn rnernbers, and since conflict is often a major

waste of time and

it is certainly a task worth performing well-and one

that will help the new venture utilize its human resotirces to the fullest.

152 PART 2

Dilbert

Assembling the Resources

NOTICE THAT I

TOOK YOUR t-\ONEY

AND I'M GivtNG

YOU Alt-\OST

NOTHING IN

RETURN.

1ii

i:5

Ci!

E

"'

"0

..::

Source: United Feature Syndicate, December 29, 1999.

Figure 5.10 Fairness: An lmportant lssue for Entrepreneurs, Investors and Everyone Else

Do you think this exchange is fair? Probably not! Although Dogbert provides the executives shown here with something

(e.g., experience in being cheated), few people would view this situation as fair. in fact, perceived fairness is a key issue in virtua/ly

a/1 working relationships, including those between cofounders of new ventures, founders and employees, and the new venture

and its customers.

One more point: Issues of faimess arise not only between cofounders, but

also between investors and entrepreneurs, between founders of a new venture

and their employees, and in fact, in all working relationships. For instance,

take a look at the situation shown in Figure 5.10. In it, one character seems to

be taking unfair advantage of another, which, as you probably know from

your own experience, can set the stage for major problems.

Issues of fairness also arise when companies form business alliances.

As we'll note in Chapter 10, such alliances can often be extremely helpful

to new ventures, but in order to survive, they must be perceived as fair

and mutually beneficial by both sides. Here's one example of a successful

alliance. 8minuteDating is a cornpany with an idea that has taken the

matchmaking industry by storm. At 8minuteDating events, single men and

warnen gather at a restaurant, chat in couples for eight minutes, and then

move on to the next table, where they meet another person (see Figure 5.11).

Figure 5.11 Fairness: A Key Principle in Business Alliances

Business alliances can be highly beneficial to entrepreneurs, but in order to succeed, both sides must perceive them as fair and as yielding

real benefits. This is definitely the case for the alliance between BminuteDating and TP/, lnc. BminuteDating encourages people

pqrticipating in its dating events to check out the personal columns, and TPI promotes BminuteDating in the personal columns it

runs for 550

r

)

i

1 r

! -

}

r

r

r

r

Ir

I

I I

r r

r

r

r

11

C HA PT ER. 5 Assembling the Team: Acquiring and Utilizing Essential Human Capital 153

This format allows each person participating in the event to meet many

potential partners in one evening instead of just one, as is true in traditional

dating. After the event is over, couples who have expressed liking for each

other can meet again. Recently, 8minuteDating formed an alliance with Tele-

Publishing International (TPI)-a company that runs the personalad pages

for 550 newspapers in the United States. How did this alliance come about?

The faunder of 8minuteDating, Tom Jafee, learned that Adam Segal, an

executive with TPI, was having dinner with his mother at a restaurant where

an 8minuteDating event was being held. Jafee introduced hirnself and the

two entrepreneurs quickly realized that they could form a mutually

beneficial alliance: TPI would advertise 8minuteDating in its personal

columns, and 8minuteDating events would distribute free coupans and

sponsor other promotions to encourage its customers to try the personal ads.

The alliance worked like a charm, and both companies benefited consider-

ably. Both see it as fair, and as helping them to attain their major goals. As

Segal puts it, "The beauty of our alliance is that it can expand with

8minuteDating's growth. Every time they start events in a new city, TPI will

already be there with our personal ads in the newspapers. Talk about a

match made in heaven." So if you consider forming an alliance with another

company, please do devote careful attention to the question of fairness:

Alliances that are not perceived as meeting this essential criterion are

unlikely to survive.

~ t e c t i v e C()tnJnMiui.tMtt

Perceived unfairness is not the only cause of costly conflicts between members

oLa new venture' s founding team. Another major factor involves faulty styles

ofcommunication. Unfortunately, individuals often communicate with others

in a way that angers or annoys the recipients, even when it is not their

intention to do so. This situation arises in many different ways, but one of the

most common-and important-involves delivering feedback, especially

negative feedback, in an inappropriate manner. In essence, the only truly

rational reason for delivering negative feedback to another person is to help

this person improve. Yet, people often deliver negative feedback for other

reasons, such as to put the recipient in his or her "place," to cause this person

to lose face in front of others, to express anger and hostility, and so on. The

result of such negative feedback is that the recipient experiences anger or

humiliation, which can be the basis for smoldering resentrnent and Iang-

lasting grudges.

34

When negative feedback is delivered in an informal context,

rather than formally (e.g., as part of a written performance review), it is known

as criticism, and research findings suggest that such feedback can take two

distinct forms: constructive criticism, which is truly designed to help. the

recipient improve, and destructive criticism, which is perceived-rightly so-as

a form of hostility or attack.

What makes criticism constructive or destructive in nature? Key differ-

ences are outlined in Table 5.1. As you can see from this table, constructive

criticism is considerate of the recipient's feelings, does not contain threats, is

timely (occurs at an appropriate point in time), does not attribute blame to the

recipient, is spedfic in content, and offers concrete suggestions for improve-

ment. Destructive criticism, in cont;rast, is harsh, contains threats, is not timely,

blames the recipient for negative outcomes, is not specific in content, and offers

no concrete ideas for improvement. Table 5.1 also provides examples of each

type of criticism.

Research findings indicate that destructive criticism is truly destructive: It

generates strong negative reactions in recipients, and can initiate a vicious

cycle of anger, the desire for revenge, and subsequent conflict. In other words,

it tends to generate what is known as affective or emotional conflict-conflict

learning

objective

7

Explain the difference

between constructive

and destructive

criticism.

154 PART 2 Assembling the Resources

Tab(e 5.1 Constructive versus Destrcutive Criticism

As shown here, constructive criticism is negative feedback that can actuatly he(p the recipient improve. Destructive criticism, in contrast,

is far tess likety to produce such beneficiat effects.

Considerate-protects self-esteem

of recipients

Does not contain threats

limely-occurs as soon as possible

after the poor or inadequate

performance

Does not attribute poor

performance to intemaf causes

Specific-focuses on aspects of

performance that were inadequate

Focuses on performance,

not the recipient

Offers concrete suggestions

for improvement

lnconsiderate-harsh, sarcastic,

biting

Contains Ihreals

Not timely-occurs after an

inappropriate delay

Attributes poor performance

to intemal causes

General-a sweeping

condemnation of performance

Focuses on the recipient

Does not offer concrete

suggestions for improvement

Constructive: "I was disappointed in your performance."

Destructive: "What a rotten, lousy job!"

Constructive: "I !hink improvement is really important."

. Destructive: "lf you don't improve, you are history!"

Constructive: "You made several errors in today's report."

Destructive: "l've been meaning to tell about the errors

you made last year ... "

Constructive: "I know that a Iot of factors probably played a role

in your performance."

Destructive: "You failed because you just don't give a damn!"

Constructive: ''The main problern was that the project was Iaie."

Destructive: "You did a r ~ l l y tenibfe job."

Constructive: "Your performance was not what I expected."

Destructive: "You are a rotten performerl"

Constructive: "Here's how I think you can do better next

time areund . _ . "

Destructive: "You better work on doing better!"

that is based largely an negative emotions. Such conflict can be costly for any

working relationship and can truly disrupt relations between founding team

rnembers.

35

In contrast, another kind of conflict that is focused an rational

disagreernents over ideas or strategies-cognitive conflict-can actually be

beneficial, because it Ieads to careful discussion of points of disagreement.

Once again, the basic message for entrepreneurs is clear: Effective

comrnunication between cofounders is one essential ingredient in establish-

lng and maintaining effective working relationships. If it is lacking, serious

problerns may result. For instance, consider a new venture started by

partners who have divergent training and experience: one is an engineer and

the other has a background in marketing. Although the marketing cofounder

selected his partner carefully, he harbors negative feelings about engineers

(''They never think about people!"). As a result, he criticizes the engineer's

designs for new products very harshly. The engineer, offended by this

treatment, begins to make changes in the company's products without

informing the cofounder. Because the marketing entrepreneur doesn't know

about these changes, he can't get customer input before they are made. The

result? The cornpany's products "bomb" in the rnarketplace, and soon the new

venture is in deep trouble. This is just one example of how faulty comm'uni-

cation between mernbers of the founding tearn can produce disastraus effects.

The rnain point should be clear: Strang efforts to attain good, constructive

communication bctwccn co-fow1ders are very worthwhile.

One final point: Is all conflict between founding co-founders bad?

Absolutely not. Conflict between tearn rnernbers can, if it is focused on

specific issues rather than personalities, and is held within rational bounds, be

very useful. Such "rational" conflict can help to focus attention an important

issues, rnotivate both sides to understand each others' view more clearly, and

can, by encouraging both sides to carefully consider all assurnptions, lead to

better decisions.

36

In surn, conflict between founding team mernbers is not

necessariiy a bad thing. Rather, it-like all other aspects of the new venture's

opetations-should be carefully rnanaged so that benefits are rnaximized and

costs minimized. Overall, strong and effective working relationships between

founding mernbers are a powerful asset to any new venture, so efforts to foster

thern should be high an every founding team' s "Must Da" list.

l

l

r

f

r

r

r

[

r

r

[

n

11

i !

f'

~ !

l'

j .

.. ~ ..

.::..

204

tJ6 j-eclitJe5

c::ittn 'Madiny thi; c.hapte,, jMU ;l1t>uld 6e a61e tt>:

1 Describe the basic nature of a business plan and

explain why entrepreneurs should write one.

2 Explain how the process of persuasion plays a key

role in business plans and in the success of new

ventures.

3 Explain why the executive summary is an important

part of any business plan.

4 Describe the major sections of a business plan and

the type of information they should include.

5 Describe the "seven deadly sins" of business plans-

errors all entrepreneurs should avoid.

6 Explain how venture capitalists actually make their

decisions about whether to provide financial support

to new ventures.

7 Explain why the quality of a new venture's businessplan

is not always a good predictor of the new venture's

future success.

8 Describe the steps entrepreneurs should take to

make their verbal prcscntations to potential investors

truly excellent.

L

p

I I

l .l

i

1

,-,

I.

C HA PT ER 7 Writing an Effective Business Plan: Building a Roadmap to Success 205

There is a real magic in enthusiasm. lt spells the difference between

mediocrity and accomplishment.

Whether they realize it or not, most entrepreneurs accept

these words as true. They are convinced that because

they believe passionately in their ideas and their new

ventures, others will too. As a result, they are often

dismayed when their initial efforts to obtain financial

backing meet with lukewarm receptions {or worse!) from

venture capitalists, business angels, and others who can,

if they wish, provide the resources the entrepreneurs

need. "What's wrang with these people?" they wonder.

"Can't they recognize a great thing when they see it?"

The problem, of course, may not be a Iack of good

judgment on the part of potential investors. Rather, it may

have much more to do with the kind of job the

entrepreneur is doing in presenting her or his idea to