Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Article 2

Transféré par

Jennifer HaleyDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Article 2

Transféré par

Jennifer HaleyDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

10.5464.AMBPP.2011.150.

ETHICAL LEADERSHIP AND MOTIVATION: EXAMINING PROMOTION AND PREVENTION REGULATORY FOCI PING SHAO College of Business Administration California State University, Sacramento Sacramento, CA 95819 CHRISTIAN J. RESICK Drexel University JOHN M. SCHAUBROECK Michigan State University ABSTRACT Drawing upon regulatory focus theory, we propose the construct of ethical regulatory focus to study ethics-related motivation, and examine its relationships with ethics-based leadership and ethical/unethical conduct. We propose that ethical leadership (EL) induces an ethical prevention focus and an ethical promotion focus in employees, and that charismatic ethical leadership (CEL) moderates the relationship between EL and employee ethical promotion focus. We also expect that ethical prevention focus motivates the avoidance of unethical conduct, whereas ethical promotion focus motivates ethical conduct. We collected data from employees and their immediate supervisors at two time-points. Results indicated that EL was positively related to both employee ethical prevention and promotion focus, and that CEL moderated the EL-to-ethical promotion focus relationship. In turn, ethical promotion focus mediated the relationship between EL and employee altruism behavior; while ethical prevention focus mediated the relationship between EL and employee deviance. INTRODUCTION Leadership is an important contextual factor that shapes employees ethical conduct in the workplace (e.g., Grojean, Resick, Dickson, & Smith, 2004). A growing body of research demonstrates empirical support for the positive impact of ethical leadership on employee behavior and beliefs (e.g., Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes, & Salvador, 2009; Walumbwa & Schaubroeck, 2009). However, there is a dearth of research on the psychological mechanisms through which ethical leaders motivate the engagement in ethical conduct or avoidance of unethical conduct. In addition, much of the prior research has examined ethical leadership using Brown, Trevio and Harrisons (2005) measure of ethical leadership which primarily uses a transactional approach to leadership (Brown & Trevio, 2006a). Others have suggest that, in addition to the transactions elements, ethical leadership has a motivational component (e.g., Resick, Mitchelson, Dickson, & Hanges, 2009) and that socialized charismatic leadership is an ethical form of leadership (e.g., Brown & Trevio, 2006b). Research is needed to determine the extent to which motivational elements of ethical leadership interact with transactional elements.

10.5464.AMBPP.2011.150.a

The purpose of the current study is two-fold. First, we propose the construct of ethical regulatory focus to study ethical motivation. We examine its relationships with forms of ethicsbased leadership, and employee ethical and unethical conduct. Rests (1986) four stage model, including moral or ethical awareness, judgment, intention/motivation, and behavior has provided a conceptual framework guiding much of ethical decision-making and behavior research. Building on this model, Trevio, Weaver, and Reynolds (2006) proposed that research is needed to better understand the cognitive and affective motivational bases of ethical (and unethical) behavior. As such, we draw upon regulatory focus theory and the approach and avoidance motivation paradigm (Higgins, 1997) to propose that ethical regulatory focus acts as a motivational mechanism linking ethical leadership and employee ethical conduct. Second, we seek to extend the understanding of dimensions of ethical leadership by proposing the construct of charismatic ethical leadership (CEL), which reflects employees perceptions of the extent to which their leaders are inspirational figures who convey ethical values, are other centered rather than self-centered, and who role model ethical conduct (Brown & Trevio, 2006b: 955). THEORETICAL OVERVIEW AND HYPOTHESES Regulatory Focus and Ethical Motivation Higgins (1997) proposed that there are two basic self-regulatory systems. The promotion focused system regulates behavior toward achievement striving and realizing the ideal self, while the prevention focused system regulates behavior toward avoidance of failure and realizing the ought self. Accordingly, we define an ethical promotion focus as a psychological state that focuses on achieving moral ideals that are desired but not necessarily mandatory or required. Conversely, ethical prevention focus is a psychological state that focuses doing what one ethical ought to do or ought not to do (e.g., obeying laws, rules and regulations). Ethics-Based Leadership Prior research has demonstrated that leader behavior can prime employees situational self-regulatory focus (e.g., Neubert, Kacmar, Carlson, & Chonko, 2008). Ethical leaders are salient organizational members who provide cues that impact employees ethical decision making. Taking a social learning perspective, Brown and colleagues (2005) defined ethical leadership as the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making (p. 120). We propose that ethical leadership induces an ethical promotion focus and an ethical prevention focus in employees. In addition, we propose that CEL moderates the relationship between ethical leadership and ethical promotion focus such that ethical leadership has a stronger effect on ethical promotion focus when the leader also demonstrates high (as opposed to low) levels of CEL. Ethical Regulatory Focus and Ethical/Unethical Behavior An activated regulatory focus (promotion-focused or prevention-focused) is a strong predictor of judgments, thoughts, and behaviors (e.g., Friedman & Forster, 2001). A prevention focus regulates pain and punishment avoidance and emphasized meeting basic safety and

10.5464.AMBPP.2011.150.a

security needs. Unethical behaviors violate rules and regulations. We expect that employees with an activated ethical prevention focus will avoid engaging in unethical behaviors. Further, we predict that ethical prevention focus mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and employee unethical conduct. In contrast, a promotion focus involves striving to reduce the discrepancy between the actual self and the ideal self. We expect that an activated ethical promotion focus will manifest in behaviors that are beneficial to others, that reflect moral ideals, and which exceed minimum normative expectations (virtuous-ethical behavior), such as whistleblowing and altruistic behavior. Therefore, we expect that ethical promotion focus provides a motivational basis for virtuous-ethical behavior. We also predict that ethical promotion focus mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and employee virtuous-ethical behavior. METHOD We developed an ethical regulatory focus measure and examined its factor structure among a sample of 218 employed individuals in the U.S. that were contacted through the StudyResponse Project. The final scale includes six items measuring ethical promotion focus and six items measuring ethical prevention focus. Acceptable internal consistency reliabilities were found for the ethical promotion ( = .91) and ethical prevention focus ( = .86) dimensions. To test the proposed relationships, data were collected from 167 supervisor-employee dyads using the StudyResponse project. Participants were U.S. citizens who were employed fulltime; employee participants received two $7.00 gift cards and supervisor participants received one $7 gift card. Data were collected in two-waves. At Time 1, employees completed measures of control variables (positive affect, = .88; negative affect, = .92; chronic promotion focus, = .88; and chronic prevention focus, = .90), ethical leadership (Brown et al., 2005, = .90), and CEL (adapting items from the MLQ, Bass & Avolio, 2000, = .95). Also at Time 1, supervisors completed measures of employee altruistic behavior (Podsakoff, Ahearne, & Mackenzie, 1997, = .94), reporting behavior (adapting items from Brown et al., 2005, = .85), and interpersonal ( = .96) and organizational ( = .97) deviance (Bennett and Robinson, 2000). At Time 2 (three weeks later), employees completed measures of ethical promotion focus ( = .90) and ethical prevention focus ( = .86). RESULTS Data were analyzed using hierarchical multiple regression. Results indicate that ethical leadership is positively related to both ethical prevention focus ( = .24, p < .01) and ethical promotion focus ( = .22, p < .01). In addition, CEL moderated the relationship between ethical leadership and ethical promotion focus ( = -.11, p < .05). In general, the trend between ethical leadership and ethical promotion focus was positive regardless as to whether employees rated their supervisors high or low in CEL. However, the trend was unexpectedly stronger among employees who rated their supervisor low on CEL. That is, ethical leadership has the strongest effect in inducing employees ethical promotion focus when CEL was low. In turn, ethical prevention focus was negatively related to supervisor-rated organizational deviance ( = -.18, p < .05) and interpersonal deviance ( = -.17, p < .05); whereas ethical promotion focus was positively related to supervisor-rated altruistic behavior ( = .44, p < .01) but not related to reporting behavior ( = .20, ns).

10.5464.AMBPP.2011.150.a

To determine the significance of indirect effects we conducted bias-corrected bootstrapping analyses using a macro developed by Preacher and Hayes (2008). The results of the bootstrapping analyses demonstrated that ethical leadership has a significant indirect effect on supervisor-rated employee interpersonal deviance (point estimate = -.08, 95% CI [-.1950, .0146]) and supervisor-rated employee organizational deviance (point estimate = -.08, 95% CI [.1904. -.0192]) through ethical prevention focus. In addition, results indicated that ethical leadership has a significant indirect effect on supervisor-rated employee altruistic behavior (point estimate = .2123, 95% CI [.0573, .4676]) through ethical promotion focus. DISCUSSION Implications for Theory and Research The current study has several implications for theory and research. First, this study proposes the ethical regulatory focus construct and presents a measure that captures the regulation of ethical conduct in the workplace. This construct and measure differs from Lockwood, Jordan and Kundas (2002) measure which focuses on a chronic promotion and prevention regulatory focus. In addition, the ethical regulatory focus measures explained incremental variance in ethical and unethical conduct beyond the effects of chronic regulatory foci. Research has demonstrated that self-related concepts serve as powerful determinants of peoples motivation and behavior (Markus & Wurf, 1987). We found a number of relationships between ethical regulatory foci and employees ethical/unethical behavior. As such, findings of this study provide evidence of the utility of the ethical regulatory focus construct for understanding the motivational bases of ethics-related behavior. Second, this study contributes to behavioral ethics literatures by indicating that people develop a form of ethics-focused cognitive motivation. In turn, this type of motivation serves as a basis for regulating the engagement in ethical behavior or avoidance of unethical behavior. Third, this study provides evidence of the importance of examined both transactional and motivational approaches to ethical leadership. As expected, ethical leadership was positively related to employee ethical promotion focus regardless as to whether the supervisor also demonstrated high or low levels of CEL. Interestingly, and unexpectedly, the strongest effects were found when the supervisor demonstrated low as opposed to high levels of CEL. This is, transactional-based approaches to ethical leadership may have their strongest effects in the absence of motivational-based approaches to ethical leadership. In addition, employees who worked for a supervisor who demonstrated lower levels of ethical leadership reported higher levels of ethical promotion focus if they worked for a supervisor who demonstrated high as opposed to low levels of CEL. That is, high CEL may compensate for lower levels of ethical leadership. This finding should be examined further in future research. Managerial Implications The current study also has implications for managers and organizations. The findings provide evidence that distinct regulatory focus mechanism provide a motivational basis for

10.5464.AMBPP.2011.150.a

understanding employees avoidance of unethical conduct and engagement in virtuous-ethical behavior. Training programs and codes of conduct are likely to impact both ethical promotion and prevent focus mindsets. More importantly, selecting and developing ethics-driven leaders will provide roles models of appropriate conduct who establish clear ethical expectations and hold themselves and others accountable. These individuals are likely to have a substantial impact on levels of ethical and unethical behavior by impacting how employees regulate the promotion and prevention of ethics-related behavior. Conclusions Aristotle once noted: The spirit of morality is awakened in the individual only through the witness and conduct of a moral person (Aristotle, 1941). The current study highlights the role of ethics-based leadership in arousing ethics-related motivation in their employees and establishing the tone for moral conduct in the workplace. REFERENCES Aristotle. 1941. Nichomachean ethics (W. D. Ross, Trans.). Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. 2000. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. 2000. Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85: 349-360. Brown, M. E. & Trevio, L. K. 2006a. Ethical leadership: a review and future directions. Leadership Quarterly, 17: 595-616. Brown, M. E. & Trevio, L. K. 2006b. Socialized Charismatic Leadership, Values Congruence, and Deviance in Work Groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91: 954 962 Brown, M. E., Trevio, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. 2005. Ethical leadership : A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97: 117-134. Friedman, R.S., & Forster, J. 2001. The effects of promotion and prevention cues on creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81: 1001-1013. Grojean, M. W., Resick, C. J., Dickson, M.W. & Smith, D. B. 2004. Leaders, Values, and Organizational Climate: Examining Leadership Strategies for Establishing an Organizational Climate Regarding Ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 55: 223241. Higgins, E. T. 1997. Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52: 1280 1300. Lockwood, P., Jordan, C., & Kunda, Z. 2002. Motivation by positive or negative role models: regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83: 854864. Markus, H., & Wurf, E. 1987. The dynamic self-concept: A social psychological perspective.

10.5464.AMBPP.2011.150.a

Annual Review of Psychology, 38: 299337. Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. 2009. How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108: 1-13. Neubert, M. J., Kacmar, K. M., Carlson, D. S. & Chonko, L. B. 2008. Regulatory focus as a mediator of the influence of initiating structure and servant leadership on employee behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93: 12201233. Podsakoff, P. M., Ahearne, M., & MacKenzie, S. B. 1997. Organizational citizenship behavior and the quantity and quality of work group performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82: 262270. Preacher, K. J., Hayes, A. F. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40: 879891. Resick, C. J., Mitchelson, J. K., Dickson, M. W., & Hanges, P. J. 2009. Culture, corruption, and the endorsement of ethical leadership. In W. Mobley, Y. Wang, & M. Li (Eds.), Advances in Global Leadership, V: 113-144. Rest, J. R. 1986. Moral development: Advances in research and theory. Trevio, L. K., Weaver, G. R. & Reynolds, S. J. 2006. Behavioral ethics in organizations: a review. Journal of Management, 32: 951-990 Walumbwa, F. O. & Schaubroeck, J. M. 2009. Leader Personality Traits and Employee Voice Behavior: Mediating Roles of Ethical Leadership and Work Group Psychological Safety. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94: 1275-1286.

Copyright of Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings is the property of Academy of Management and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The First Return To The PhilippinesDocument28 pagesThe First Return To The PhilippinesDianne T. De JesusPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Brunei Empire and DeclineDocument4 pagesHistory of Brunei Empire and Declineたつき タイトーPas encore d'évaluation

- This Content Downloaded From 181.65.56.6 On Mon, 12 Oct 2020 21:09:21 UTCDocument23 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 181.65.56.6 On Mon, 12 Oct 2020 21:09:21 UTCDennys VirhuezPas encore d'évaluation

- Approvalsand Notificationsfor Authorisersand RequisitionersDocument15 pagesApprovalsand Notificationsfor Authorisersand RequisitionersSharif AshaPas encore d'évaluation

- VisitBit - Free Bitcoin! Instant Payments!Document14 pagesVisitBit - Free Bitcoin! Instant Payments!Saf Bes100% (3)

- Pennycook Plagiarims PresentationDocument15 pagesPennycook Plagiarims Presentationtsara90Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 2Document16 pagesChapter 2golfwomann100% (1)

- Anthropology Paper 1 Pyq AnalysisDocument6 pagesAnthropology Paper 1 Pyq AnalysisRimita Saha100% (1)

- Export-Import Fertilizer ContractDocument36 pagesExport-Import Fertilizer ContractNga LaPas encore d'évaluation

- English For Informatics EngineeringDocument32 pagesEnglish For Informatics EngineeringDiana Urian100% (1)

- AXIOLOGY PowerpointpresntationDocument16 pagesAXIOLOGY Powerpointpresntationrahmanilham100% (1)

- Chapter 1: Solving Problems and ContextDocument2 pagesChapter 1: Solving Problems and ContextJohn Carlo RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Corporate Surety BondsDocument9 pagesCorporate Surety BondsmissyaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Varifuel2 300-190 30.45.300-190D: Technical Reference Material Created by DateDocument1 pageVarifuel2 300-190 30.45.300-190D: Technical Reference Material Created by DateRIGOBERTO LOZANO MOLINAPas encore d'évaluation

- Qualities of Officiating OfficialsDocument3 pagesQualities of Officiating OfficialsMark Anthony Estoque Dusal75% (4)

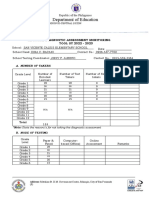

- Regional Diagnostic Assessment Report SY 2022-2023Document3 pagesRegional Diagnostic Assessment Report SY 2022-2023Dina BacaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Electrical Energy Audit and SafetyDocument13 pagesElectrical Energy Audit and SafetyRam Kapur100% (1)

- Reading Literature and Writing Argument 6th Edition Ebook PDFDocument33 pagesReading Literature and Writing Argument 6th Edition Ebook PDFsamantha.ryan702100% (33)

- Cover Letter - EyDocument1 pageCover Letter - Eyapi-279602880Pas encore d'évaluation

- 55850bos45243cp2 PDFDocument58 pages55850bos45243cp2 PDFHarshal JainPas encore d'évaluation

- Liberal Arts Reading ListDocument2 pagesLiberal Arts Reading ListAnonymous 7uD3SBhPas encore d'évaluation

- Swiis Statement of PurposeDocument12 pagesSwiis Statement of PurposeIonaDavisPas encore d'évaluation

- Macn000000315+111 (USAA) Universal Sovereign Original Indigenous Natural Divine Affidavit Ov Written Innitial Unniversal Commercial Code 1 Phinansinge Statement LienDocument5 pagesMacn000000315+111 (USAA) Universal Sovereign Original Indigenous Natural Divine Affidavit Ov Written Innitial Unniversal Commercial Code 1 Phinansinge Statement Liencarolyn linda wiggins el all rights exercised and retained at all timesPas encore d'évaluation

- Variety July 19 2017Document130 pagesVariety July 19 2017jcramirezfigueroaPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary of EcclesiastesDocument6 pagesSummary of EcclesiastesDavePas encore d'évaluation

- Arvind Goyal Final ProjectDocument78 pagesArvind Goyal Final ProjectSingh GurpreetPas encore d'évaluation

- Dissertation 1984 OrwellDocument6 pagesDissertation 1984 OrwellCanSomeoneWriteMyPaperForMeMadison100% (1)

- Symptomatic-Asymptomatic - MedlinePlus Medical EncyclopediaDocument4 pagesSymptomatic-Asymptomatic - MedlinePlus Medical EncyclopediaNISAR_786Pas encore d'évaluation

- Green BuildingDocument25 pagesGreen BuildingLAksh MAdaan100% (1)

- Dinie Zulkernain: Marketing Executive / Project ManagerDocument2 pagesDinie Zulkernain: Marketing Executive / Project ManagerZakri YusofPas encore d'évaluation