Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Abram Trosky, Integrative Summary of War, Torture, and Terror

Transféré par

PhDJDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Abram Trosky, Integrative Summary of War, Torture, and Terror

Transféré par

PhDJDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

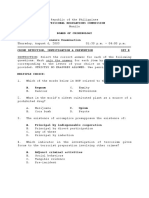

Integrative Summary for Definitions of War, Torture, and Terrorism Abram Trosky

War, terrorism, and torture can each be thought of as forms of political violence violence used as a means to achieve some group endbut with different conceptions of what that end permits. In contrast to the indiscriminate or symbolic violence of terror, war has traditionally been between national militaries on delimited fields of battle. In theory, the violence that characterizes modern military warfare is similarly bounded, tactical, and directed. However, insufficient international regulation of weapons-as-aid from developed into developing countries and recirculation of Cold War munitions stockpiles on the black market have contributed to a dangerous decentralization of force. Asymmetric conflicts involving militias and other non-state actors in Afghanistan to Colombia, and the Congo can often be bloodier and more protracted than conventional warfare, with higher levels of civilian displacement and death. Despite the periodic romanticization of both kinds of warfare, survivors tell horror stories of wanton pain, suffering, and death that belie the awful, inertial power of organized violence. These tales testify to how easily the line between the supposedly instrumental violence of war, and more callous killing of terror is blurred in wars fog. Repeated failures in the tactical use of torturethe supposedly controlled application of physical or psychological force to individualsgive similar testimony of the difficulty in domesticating violence. While no one celebrates cruelty, cultures of all kinds manage to recreate conditions in which sanctioned group violence spirals into something more sadistic.

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

However paradoxically, the fact that statespersons regularly euphemize violence to morally justify its use demonstrates the power that public opinion carries: cynical leaders still feel required to speak the language of legitimacy when presenting the case for war. The recurrence of common themes in these appeals indicates the persistence of some shared morality regarding violence, even in a postmodern age (Walzer, 2006, p. xxi). Although torture is relatively morally unambiguous, wars of words are still being fought over whether there are authentic justifications for war and terror; hence the importance of this chapter cataloguing definitions of these concepts from around the world. First, we present integrative definitions of each.

War The moral and legal status of states use of force has long been debated in the context of political expediency: when, if ever, do political endsthe projected good of some privileged majority or minorityjustify war and its attendant risks? Are there times when leaders are permitted to trade the life of a few to save many? Soldiers are unique in that their oath of enlistment places their lives in the absolute service of these decisionmakers as the primary currency of such cost/benefit analyses. But how to identify the institutions and rationales that demand these risks unnecessarily, hiding underlying atavistic motives in the resort to war? Machiavelli thought that the unquestioning allegiance of citizen-soldiers, where countrymen would fight for ideas, not merely survival, was the principal virtue of a republic. Lenin thought that this was the nations main liability. Kant proposed that with the rise of republics, warmongering would be self-

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

regulated. Citizens everywhere would resist hostilities, which interrupted commerce, and protest the increased taxes needed to fund standing armies. All three scenarios suggest governmental pressure to convince national populations of the necessity of sacrifice is a constant (though not always disingenuous). Because national motives are nearly always mixed and even democratic states nonunitary actors, an example of a just war seems as elusive or irrelevant as a Platonic Form. This elusiveness leads most respondents to our Personal and Institutional Rights to Aggression and Peace Survey (PAIRTAPS) to one of two conclusions regarding war: general condemnation and the pacifistic hope of its elimination on the one hand; on the other, the realist recognition that the permanence of wars threat is strong reason to eliminate sentimental moral considerations in the struggle for survival. In the absence of a pure case, this polarization may be an example of the perfect becoming enemy to the good in the relationship of public opinion to international ethics. However, neither historys sordid chronicling of one war after another, nor wars projected persistence obviate the question of how humans should fight, to which precise definitions of proscribed tactics, such as torture and terror, remain extremely relevant.

Terrorism Because government officials are prone not only to national aggrandizement, but self-aggrandizement as well, citizens opposing antidemocratic leaders also grapple with questions regarding the morality of violence. Although the state is defined by its monopoly on violence (Weber, 2004, 29) (or more precisely, on the legitimate use of force), the law recognizes certain justified uses of lethal force by individuals and nations

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

against each other, most commonly in self-defense. There is longstanding debate in political theory over the threshold of injustice that warrants forceful resistance (McMahan, 2005). Does a threat need to be existential to be intolerable? Does the immorality of a law or government ever justify the use of violence against it? That people can resist is the premise of civil disobedience, and is relatively uncontroversial; how they resist is crucial in answering these questions. If laws systematically deprive a group of the very rights upon which that laws authority is based (life, liberty, property), that group might be justified in foregoing attempts at peaceful resistance and use targeted force against the system of law itself (Locke, 1980, vii). As activist and author of Disobedience and Democracy Howard Zinn (2001) points out, such a focused act of violence may not be lawful, but it still can be just. Terrorism is defined by the use of tactics that cross this line. Its object is not limited to the system itself, but extends to citizens, who are seen as complicit in injustice by virtue of their silent consent. They are seen as guilty of inaction. However, the morally relativistic refrain, one groups terrorist is anothers freedom fighter misses the fact that terrorism is not merely a label that groups in power use to smear their opponents; it has a real-world referentthe callous killing of noncombatantsof which either side may be guilty. No causenot freedom nor the end of war itselfcan morally justify the intentional sacrifice of innocents against their will; this much is self-evident (Etzioni, 2010). Without some universal standard like the respect for human rights that now animates international law, justice devolves to the right of the stronger. Recognition of a common legal, if not moral, framework raises another timely question about the norms of domestic and international politics and the relationship of

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

war to terror: If a citizens movement resists an oppressive government justly (that is, without resorting to terror), but revolutionary conditions deteriorate, thereby threatening civil war or state failure, do neighboring countries and/or other members of the international community have a right or duty to intervene? The opinion of the United Nations on this issue has evolved over the last decade, positing (2001, 2005) and reaffirming (2006, 2009) a Responsibility to Protect (R2P) that justifies multilateral intervention in four extreme cases: genocide, ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity, and war crimes (United Nations, 2005). In these cases, it could be said that the offending government is itself guilty of terrorism against its own people, who are justified in defending themselves as others are in coming to their aid. However, R2P exhausts neither the possible definitions of state terror, nor the possible justifications for intervention. Between headings on Use of force under the Charter and Peacekeeping, the same document that formalizes R2P features a separate section strongly condemning terrorism. Naming it as one of the most serious threats to international peace and security, the UN affirms as part of its mission, To maintain international peace and security, and to that end: to take effective collective measures for the prevention and removal of threats to the peace, and for the suppression of acts of aggression or other breaches of the peace, and to bring about by peaceful means, and in conformity with the principles of justice and international law, adjustment or settlement of international disputes or situations which might lead to a breach of the peace (UN, 2005) Central among these principles is respect for that venerable cornerstone of international law, national sovereignty. This clause serves as a warning to intervening nations, especially those doing so unilaterally and with lethal force, that they too can easily present a threat to peace.

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

Although human rights activists rightly bemoan the euphemization of unintentional but foreseeable civilian deaths incurred during wartime operations as collateral damage, these do not represent war crimes. However, if soldiers of the invading nation incur avoidable/nonessential civilian casualties, even under the pretense of aiding oppressed others, the legal distinction between them and the aggressors against whom they are ostensibly fighting begins to break down. When such deaths are systematic, repeated, and reckless, the intervening nation may also be guilty of state terror, or aggression, the supreme international crime (Jackson, 1949). Fighting terror is not an exemption from the prohibition against terror. The violation of national sovereignty is, under certain circumstances, legally and morally permissible; the violation of international humanitarian law is not. In the terminology of the just war tradition, legitimacy in permission to go to war (jus ad bellum) does not provide blanket immunity for illegitimacy in its execution (jus in bello). This distinction is captured in the following paragraph from the 2005 UN World Summit under the heading Terrorism: We recognize that international cooperation to fight terrorism must be conducted in conformity with international law, including the Charter and relevant international conventions and protocols. States must ensure that any measures taken to combat terrorism comply with their obligations under international law, in particular human rights law, refugee law and international humanitarian law (UN, 2005). Although this document does not mention torture, a resolution by the UN Security Council the next year, Reaffirms also its condemnation in the strongest terms of all acts of violence or abuses committed against civilians in situations of armed conflict in violation of applicable international obligations with respect in particular to (i) torture and other prohibited treatment (UN, 2006).

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

This UN resolution on state violence provides an opportunity to elaborate on international humanitarian law prohibiting torture in the context of two recent international conflictsthe U.S.-led invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan. The opening of these two fronts in the so-called War on Terror, and the debate over the definition of torture and its use in these conflicts, were relatively recent when our team administered the PAIRTAPS, and were therefore referenced frequently in qualitative responses.

Torture If terrorism is characterized by the death of innocents, can torture, which normally inflicts harm short of death on suspects presumed to be guilty, be considered a terror tactic? Torture inflicted by suspected terrorists and authoritarian dictatorships conforms to historical uses of pain to elicit confessions (Murphy, 2012). It is also used punitively to inflict mutilations or disfigurement that deter dissent and inspire fear in the populace, as in the notorious South American disappearances, Robert Mugabes systematic intimidation campaign during the 2008 elections in Zimbabwe (Godwin, 2011), or the Assad regimes atrocities against captured protestors in Syria. These varieties of torture are obvious transgressions; even if a captive is guilty of the capital offense of treason, making an example of them to would-be rebels by protracting this process through torture transgresses criminal and moral law by treating an individual as a means rather than an end in themselves (Kant, 1993, 36). By this reasoning, governments condoning the use of torture may be guilty of state terror, if not a crime against humanity, but as with the prosecution of other atrocities, it is unclear how far up the chain of command guilt reaches (Crawford, 2007).

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

The world lost a chance to locate responsibility in the case of the U.S. governments use of enhanced, severe, or aggressive interrogation techniques against two Al Qaeda operatives when, in 2005, the chief of the CIAs National Clandestine Service destroyed hundreds of hours of videotaped interrogations (Gorman & Evans, 2009). This step was supposedly taken as a precaution to protect lower-level officers who were just following orders, but may as likely have been to protect the identities of higher-level visitors who were giving the orders (Engelhardt, 2007). Could blame extend all the way to a citizenry that tolerates or even advocates their governments use of torture to keep them safe? An affirmative answer borders dangerously on the terrorists rationale for random acts of violence against the public for the sake of political expediency. Several PAIRTAPS respondents did defend the use of torture, provided it yielded information that contributed to saving lives. However, torturing a suspect to find and defuse a ticking bomb is largely the stuff of fiction; the connection and calculus between lives saved and lives damaged through advanced interrogation techniques is far more tenuous in their common application of general intelligence gathering. Mathew Alexander, the lead interrogator responsible for gathering intelligence used to track down Al-Qaeda leaders in Iraq such as Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, eschewed harsh interrogation techniques, calling them a euphemism for abuse, if not torture (Alexander, 2011). He estimates that the incentive-based, cooperative strategies his team used had an 80% success rate, but laments that these milder techniques were not widely adopted by old school interrogators (Gross & Miller, 2011). A recently declassified U.S. government document (Declassified document 000353, 2002, p. 2) corroborates his

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

methodological choice, noting The application of extreme physical and/or psychological duress (torture) has some serious operational deficits, most notably, the potential to result in unreliable information. The document goes on: This is not to say that the manipulation of the subject's environment in an effort to dislocate their expectations and induce emotional responses is not effective. On the contrary, systematic manipulation of the subject's environment is likely to result in a subject that can be exploited for intelligence information and other national strategic concerns. (Declassified document 000353, 2002, p. 2) Manipulation of the subjects environment is troublingly vague, conceivably justifying unethical privations that are elsewhere classed as psychological torture. This class includes the severe emotional abuse of no-touch torturethe sleep, exercise, and communication deprivation characteristic of solitary confinement. Despite its mention in the declassified document, the U.S. government continues to deny this or any other use of torture, calling the conditions in single occupancy cells standard for Level One military prisons such as the Marine Corps Brig at Quantico, or the Guantanamo Bay detention facility. Hostile interrogations, including those of U.S. citizens, have also taken place off American soil, during extraordinary renditions to secret prisons (so-called black sites), and, notoriously, at the U.S. prison at Abu Ghraib. Under former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, enhanced interrogation techniques previously limited to Army Special Access Programs were extended to common soldiers and national guardsmen and women. The cornerstone of enhancement in this theatre was tailored to what were seen as the specific vulnerabilities of Arabic males: coercive force coupled with sexual humiliation. This atmosphere of permissiveness vis--vis racial discrimination and religious bigotry led to

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

10

widespread abuse. The ghastly images leaked from Abu Ghraib confirmed what psychologists have known for some time: official authorization and/or belief in the sanctity of ones cause facilitates the dehumanization of victims (Milgram, 1974; Zimbardo, 1991; Bandura, 1999). Even if they had not resulted in death and maiming of subjects, these acts would normally have been prohibited by international humanitarian lawunder the third and fifth articles of the UN Declaration of Human Rights (1948)and the UN Convention Against Torture (1984). Whereas the official line has been to dismiss abuses like those at Abu Ghraib as aberrationsthe depraved acts of a few, deviant individualspsychiatrist and historian R.J. Lifton (2004) has argued that war regularly produces conditions favorable to criminal violations, with wars of counterinsurgency particularly prone to such atrocity-producing situations.

Torture, Terrorism, and War in the context of International Humanitarian Law Wars of aggression are prosecutable under the 1928 Kellogg Briand Pact (The General Treaty for the Renunciation of War), which was used as the basis for the crimes against peace prosecuted by the Nuremberg Tribunal, as well as under article two of the United Nations Charter. Wars of defense, by contrast, are protected under the UN Charters article 51 (1945), which states, Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security. In practice, because nations retain the prerogative to determine what constitutes their vital interests and to define threats to that

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

11

interest, the legality of defensive war has provided a loophole for preemptive, even preventative war-making invoked, for instance, in the Iraq and Vietnam Wars (McMahan, 2005). Critics of these wars argue that their prolonged timetables and high civilian casualties make them functionally indistinct from wars of aggression (Burke, 2004). In neither of these conflicts, nor the one in Afghanistan, has war officially been declared, each having the characteristics of counter-insurgency rather than a series of battles against a national foe that could be decisively defeated. The U.S. has portrayed the violations of national sovereignty in Afghanistan and Iraq as multilateral decisions in an attempt to legitimate them. Despite UN Security Council backing being named as a sine qua non by a majority of Americans polled for the invasion of Iraq (Benedetto, 2003), only the coalition effort in Afghanistan had this designation. Failure on this front in Iraq runs afoul of just war principles such as reasonable chance of success and authorization by legitimate authority. Revelations since the invasion point to the violation of the more fundamental just war criteria of just cause and last resort (Wilson, 2003; McMahan, 2005). Afghanistan and Iraq are seen as fronts in the War on Terror waged by the U.S. military and intelligence apparatuses, the prosecution of which raises questions in international humanitarian law. The Bush administrations unilateral declaration that suspected members of international terrorist organizations like Al Qaeda would be considered illegal combatants attempted to void their protection under the Geneva Conventions. However, low-intensity counter-insurgency warfare is covered under international humanitarian law (IHL): The third and fourth articles of the Third Geneva Convention of 1929, relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, deal expressly with

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

12

armed conflict not of an international character, mentioning torture among its prohibitions several times, as well as outrages upon personal dignity, in particular, humiliating and degrading treatment, for all category of belligerent: crew-members or laborers, correspondents or contractors, paramilitary or militia, sick or wounded (International Committee of the Red Cross, 1949). The Fourth Convention, relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, outlaws terrorist tactics such as hostage-taking, mutilation, and murder (International Committee of the Red Cross, 1949). Even though civilians and captured soldiers are accorded similar rights under these articles, the viability of IHL depends on an active distinction between these groups on the part of all involved: soldiers cannot hide among civilians and civilians cannot behave like soldiers. Members of organized resistance movements, belonging to a Party to the conflict and operating in or outside their own territory, even if this territory is occupied are also covered by the Conventions, provided they meet four conditions: (a) that of being commanded by a person responsible for his subordinates; (b) that of having a fixed distinctive sign recognizable at a distance; (c) that of carrying arms openly; (d) that of conducting their operations in accordance with the laws and customs of war (International Committee of the Red Cross, 1949). Decentralized and covert, terrorist tactics purposefully conform to none of these. However, under the same body of law, apprehended and detained terror suspects are afforded the protection against mutilation and murder that they deprived of their victims.

Conclusions

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

13

Even when respondents do not expressly invoke international law or ethics, their definitions of war, torture, and terror are drawn from one of three basic conceptions regarding the permissibility of political violence: 1) these acts and activities are unqualifiedly immoral and therefore impermissible (the position of the pacifist), 2) qualifiedly moral and permissible (the middle territory that the just war tradition is meant to navigate), or 3) amoral (the position of the foreign policy realist). In the last case, an acts permissibility is unrelated to its putative morality, and is only related to its legality insofar as it is enforceablea largely post hoc consideration in anarchic international relations. Because the validity of desperate means depends on the specific conditions under which they are deployed, as in the second and third cases, neither international law nor absolutist moral law seem adaptable enough to be useful. As undesirable as it is, war seems to admit of exception. War may be hell, but it nonetheless continues to strike citizens of disparate dispositions as occasionally necessary, albeit for different reasons. As De Mercurio et al point out in their chapter, competing conceptions of what constitutes vital national security interests range from stopping an immanent threat, to finding dragons to slay. Because of the short leap from the genuine attempt to promote global justice to governments confusing their good intention for just cause, national interests must be kept in check through citizens vigilance and participation. The findings presented in this book imply that once statespersons convince themselves of their nations stake in a particular conflict, public opinion is dangerously malleable. This is especially true when members of the media cease to be vigilant. Peacetime, therefore, ought not be considered merely the period between inevitable wars, but the time in which populaces steel themselves against

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

14

spurious official rationales for conflict, building bridges between themselves and the potential other. Misleading as the War on Terror is in naming an abstraction as a belligerent, the psychology and sociology behind the resort to terror, often by affluent and educated individuals, is a pressing area of further study. While many individuals intuitions about political rights align with the consensus in international ethics, addressing the twin scourges of aggressive war and terrorism requires continuing public education or reeducation regarding its particular moral and legal requirements. These intuitions can be overpowered by socialization into either the debilitating cultural relativism that has become prevalent in higher education, or the jingoistic ethnocentrism or militant nationalism that often characterizes populist appeals to the less well-educated. Without authentic deliberation about just reconciliation of difference, these forces threaten to undermine both the conviction behind international resolutions like the Responsibility to Protect, and the skepticism necessary to keep individual governments in check, in and out of wartime. By demanding national governments adhere to the standards set out in the UN Charter, conform to international humanitarian law, and accept the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court and International Court of Justice, citizens take collective responsibility for shaping the vaunted opinion of [hu]mankind (Walzer, 2006). Voting is too slow a mechanism to elicit such accountability; these entities and ideas must permeate political discourse about foreign affairs and electoral platforms, as well as dinnertime and work conversations. Informed opinion includes knowing, rather than guessing, what others around the world think. Thus, public opinion presented through

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

15

survey data like those that appear in this chapter, is highly relevant in progressing debate over the normative status of political violence. It is only through the negotiation of a more precise understanding of concepts like torture and terror, in their colloquial, legal, and historical uses, that we can clarify and refine the standards by which humanity defines humanity.

References

Alexander, M. (2011). Kill or capture. New York: St. Martins Press Amnesty International general information leaflet. (2005, November 1). Torture and ill treatment in the 'war on terror. Retrieved from http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/ACT40/014/2005/en Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review. [Special Issue on Evil and Violence]. 3, 193-209. Benedetto, R. (2003, March 16). Most back war but want U.N. Support. USA Today. Retrieved from http://www.usatoday.com/news/world/iraq/2003-03-16-poll-iraq_x.htm Burke, A. (2004). Just war or ethical peace? Moral discourses of strategic violence after 9/11. International Affairs. 80(2), 329-353. Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. (1949, August 12). Geneva. Retrieved from http://www.icrc.org/ihl.nsf/FULL/375?OpenDocument Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. (1949, August 12). Geneva. Retrieved from http://www.icrc.org/ihl.nsf/FULL/380?OpenDocument Crawford, N. (2007). Individual and collective moral responsibility for systemic military atrocity. The Journal of Political Philosophy. 15(2), 187-212. Joint Personnel Recovery Agency document 000353 (2002). Operational issues pertaining to the use of physical/psychological coercion in interrogation: an overview. Declassified document 000353, HG JPRACC/25 Jul 02/DSN 654-2509. Retrieved from: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/nation/pdf/JPRAMemo_042409.pdf Elsea, J.K. (2004, March 15). Detention of US citizens as enemy combatants. Congressional Research Service Report for Congress. Retrieved from http://www.fas.org/irp/crs/RL31724.pdf Engelhardt, T. (2007). Introduction. In Grandin, G. The unholy trinity: death squads, disappearances, & torturefrom Latin America to Iraq. Retrieved from http://www.coldtype.net/Assets.08/pdfs/0108.Grandin.pdf Etzioni, A. (2010). The normativity of human rights is self-evident. Human Rights Quarterly 32, 187-197.

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

16

Godwin, P. (2011). The Fear: Robert Mugabe and the martyrdom of Zimbabwe. New York: Little, Brown, & Co. Gorman, S. & Perez, E. (2009, March 3). Justice says CIA destroyed 92 tapes. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123600509352009745.html Gross, T. & Miller, D. (Co-Executive Producers). (2011, February 14). One man says no to harsh interrogation techniques. Fresh air [Radio Broadcast]. Philadelphia, PA: WHYY Studios. Hersh, S. (2004). The gray zone. The New Yorker online. Retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2004/05/24/040524fa_fact?currentPage=3 Jackson, R. H. (Chief Prosecutor) (1949, September 30). The common plan or conspiracy and aggressive war. Nuremberg trial proceedings. 22, (270) section 426. Retrieved from http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/0930-46.asp Kant, I. (1993). Grounding for the metaphysics of morals (3rd ed.). (J.W. Ellington, Trans.). Indianapolis: Hackett. (Original work published 1785). Kaplan, R. (1994). The coming anarchy. The Atlantic, Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1994/02/the-coming-anarchy/4670/ Locke, J. (1980). Second treatise of government. Indianapolis: Hackett. (Original work published 1690). McMahan, J. (2005). Just cause for war. Ethics and International Affairs, 19:3, 1-21 Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: an experimental view. London: Tavistock Publications. Murphy, C. (2012). The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Musen, K. & Zimbardo, P. G. (1991). Quiet rage: The Stanford prison study. [Videorecording]. Palo Alto, CA: Psychology Dept., Stanford University. Peterson, T. (2004). The environment creates the atrocity. Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved from http://www.businessweek.com/bwdaily/dnflash/may2004/nf20040518_9951_db028.htm Soldz, S. (2010). Experiments in torture: evidence of human subject research and experimentation in the enhanced interrogation program. Physicians for Human Rights White Paper. Retrieved from http://www.soros.org/initiatives/usprograms/focus/security/articles_publications/publications/phr-torturereport-20100607/phr-torture-report-20100607.pdf Soldz S. (2011, March 23). Public lecture. Courage to resist: Bradley Manning. Boston University Chapter, Amnesty International. Charter of the United Nations, (1945, June 26). United Nations Conference on International Organization. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/documents/charter/chapter1.shtml United Nations General Assembly. (2005, September 15). Paragraphs 138 & 139. Responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethinic cleansing, and crimes against humanity. 2005 World Summit outcome. United Nation Security Council. (2006, April 26). Resolution 1674. Retrieved from http://protection.unsudanig.org/data/sg_reports/S-Res1674%20on%20protection%20civilians%20in%20armed%20conflict%20(28Apr06).pdf

INTEGRATIVE SUMMARY DEFINITIONS

Walzer. M. (2006). In Just and unjust wars (4th ed.). New York: Basic Books. (Original work published 1977). Wilson, J. (2003, July 6). What I didnt find in Africa. The New York Times. Weber, M. (2004). Politics as a vocation. In D.S. Owen & T.B. Strong (Eds.), The Vocation Lectures. Indianapolis: Hackett. Zinn, H. (2001). A just cause, not a just war. The Progressive. Retrieved from http://www.progressive.org/0901/zinn1101.html

17

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Culture of War (2008)Document503 pagesThe Culture of War (2008)PhDJ100% (8)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Boardgame Escape From ColditzDocument3 pagesBoardgame Escape From ColditzRon Van 't VeerPas encore d'évaluation

- Cohesive Devices Exercise OdetteDocument4 pagesCohesive Devices Exercise OdetteJeanetta Jonathan100% (2)

- Social Contract Theory ExplainedDocument12 pagesSocial Contract Theory ExplainedPhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- Washington's Newburgh AddressDocument3 pagesWashington's Newburgh AddressPhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- FCE RephraseDocument9 pagesFCE RephrasePetrePas encore d'évaluation

- Reviseu Penal Coue of the Philippines Book Two Aiticles 114-S67Document66 pagesReviseu Penal Coue of the Philippines Book Two Aiticles 114-S67allukazoldyckPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs FitzgeraldDocument2 pagesPeople Vs FitzgeraldWILHELMINA CUYUGANPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Contract Theory (Locke)Document6 pagesSocial Contract Theory (Locke)PhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- The Dem-Mil Gap - An Examination of Partisanship and The ProfessionDocument39 pagesThe Dem-Mil Gap - An Examination of Partisanship and The ProfessionPhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Contract Theory (Locke)Document6 pagesSocial Contract Theory (Locke)PhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- Cultural Relativism As IdeologyDocument11 pagesCultural Relativism As IdeologyPhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- Writing in Social StudiesDocument26 pagesWriting in Social StudiesPhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- The Dem-Mil Gap - An Examination of Partisanship and The ProfessionDocument349 pagesThe Dem-Mil Gap - An Examination of Partisanship and The ProfessionPhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To The AntifederalistsDocument5 pagesIntroduction To The AntifederalistsPhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- Developments in IR TheoryDocument65 pagesDevelopments in IR TheoryPhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- The Islamic Commercial Crisis:: Institutional Roots of Economic Underdevelopment in The Middle EastDocument50 pagesThe Islamic Commercial Crisis:: Institutional Roots of Economic Underdevelopment in The Middle EastHüseyın GamtürkPas encore d'évaluation

- Supreme CommandDocument7 pagesSupreme CommandPhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- Holistic View of Human BehaviourDocument203 pagesHolistic View of Human BehaviourPhDJ100% (1)

- UPenn CONFEDERATION BibliographyDocument3 pagesUPenn CONFEDERATION BibliographyPhDJ100% (1)

- Elie Wiesel, Why I Love IsaacDocument1 pageElie Wiesel, Why I Love IsaacPhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- Ch.11 - Integrative Summary For Definitions of WTT, at Edits 2-15-12Document39 pagesCh.11 - Integrative Summary For Definitions of WTT, at Edits 2-15-12PhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- Tirman On Civilian CasualtiesDocument2 pagesTirman On Civilian CasualtiesPhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- Coexistentialism, The Philosophy of A. Nagraj SharmaDocument28 pagesCoexistentialism, The Philosophy of A. Nagraj SharmaPhDJPas encore d'évaluation

- Michael Sandel On JusticeDocument3 pagesMichael Sandel On JusticePhDJ0% (1)

- Informative EssayDocument8 pagesInformative EssayDebora Muñoz ÑurindaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cossijurah CasaeDocument15 pagesCossijurah CasaeDevansh Dubey0% (1)

- Too DearDocument4 pagesToo DearhiriyuronePas encore d'évaluation

- 331 Test 1Document4 pages331 Test 1ginny_candy100% (1)

- Incorporating The Into National Prison Legislation: Nelson Mandela RulesDocument105 pagesIncorporating The Into National Prison Legislation: Nelson Mandela RulesA SPas encore d'évaluation

- Cee C1 RB TB R4Document16 pagesCee C1 RB TB R4Javier AmatePas encore d'évaluation

- Preiser v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 475 (1973)Document38 pagesPreiser v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 475 (1973)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Custody Conditions - 23 March 2018Document2 pagesCustody Conditions - 23 March 2018Maurice John KirkPas encore d'évaluation

- SURJ Volume 13Document108 pagesSURJ Volume 13Catherine DongPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Law 5103 OF OFFENCESDocument34 pages5 Law 5103 OF OFFENCESzin minPas encore d'évaluation

- Bureau of Prisons Update 2011 Oregon Federal DefenderDocument40 pagesBureau of Prisons Update 2011 Oregon Federal Defendermary engPas encore d'évaluation

- 12-07-01 Imprisoned Court Watcher David Schied - The Judicial House of Cards and How It Is Falling Down at The Expense of The PeopleDocument5 pages12-07-01 Imprisoned Court Watcher David Schied - The Judicial House of Cards and How It Is Falling Down at The Expense of The PeopleHuman Rights Alert - NGO (RA)Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Special Powers Act 1974Document22 pagesThe Special Powers Act 1974Meena RajaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rep PayeeDocument12 pagesRep Payeermckane100% (1)

- CRIDIP 2003 With Answers OkDocument16 pagesCRIDIP 2003 With Answers OkQueen Vi BenedictoPas encore d'évaluation

- Recursos Educativos Villaeduca®: WWW - Villaeduca.Cl Consultas@Villaeduca - CLDocument1 pageRecursos Educativos Villaeduca®: WWW - Villaeduca.Cl Consultas@Villaeduca - CLKaly Araya CerdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Parole and FurloughDocument2 pagesParole and FurloughthebookclubonnPas encore d'évaluation

- History of PrisonDocument4 pagesHistory of PrisonShaira ErpePas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. McBrayer, 10th Cir. (2013)Document4 pagesUnited States v. McBrayer, 10th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument19 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Preface: Google Mahatma Gandhi's Assassination - A ROTHSCHILD ConspiracyDocument8 pagesPreface: Google Mahatma Gandhi's Assassination - A ROTHSCHILD Conspiracyhindu.nationPas encore d'évaluation

- DELHI PUBLIC SCHOOL CLASS XII ENGLISH ASSIGNMENT CYCLE 7Document4 pagesDELHI PUBLIC SCHOOL CLASS XII ENGLISH ASSIGNMENT CYCLE 7Swayam PatelPas encore d'évaluation

- John Donne Collected PoemsDocument187 pagesJohn Donne Collected PoemsEricAlanWeinsteinPas encore d'évaluation

- LOGIC CH 1 L 6Document5 pagesLOGIC CH 1 L 6amcf1992Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Anti-Cattle Rustling Law of 1974Document16 pagesThe Anti-Cattle Rustling Law of 1974cryxx jdnPas encore d'évaluation