Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The Age of Andrew Jackson

Transféré par

Jeff SerenoCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Age of Andrew Jackson

Transféré par

Jeff SerenoDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Jeff Sereno January 3, 2012 A.P. Government Mrs.

Geovanis

The Age of Jackson When Congress assembled on Dec. 7, 1829, Andrew Jackson generated a great deal of attention with his first annual address. Meeting his old friend General Robert Armstrong the next day, Jackson said, Well, Bob, what do the people say of my message? They say, replied Armstrong, that it is first-rate, but nobody believes that you wrote it. Well, said Old Hickory good-naturedly, don't I deserve just as much credit for picking out the man who could write it? One of Jacksons most celebrated abilities as president was his ability to identify pragmatic solutions to the most complex problems of the day. Throughout his presidency, Andrew Jackson confronted conflicts involving territorial expansion, entrenched political forces and public demands for increased economic opportunity, and he consistently forged effective solutions. Jacksons leadership laid the foundation for public expectations of the nations chief executive that still endure today and he left an indelible mark on American political culture. When measured against a set of seven key criteria developed by political philosopher David Gergen, (character, purpose, capacity to persuade, working with Congress, strong start, prudent advisers and a bold legacy), Jacksons presidency clearly merits the definition of great. When Andrew Jackson entered the office of president in 1828, he was known primarily as a military hero for his role as a general during the War of 1812 and his

successful leadership during the first and second Seminole Indian Wars. Jacksons campaign for president capitalized on his enviable military record and his ability to unify the nation. A fellow officer once spoke of his determination: As a general, he tended to do necessary things with great expedition and to inquire afterward into their legality (Alfred, 1356). Jacksons bold tactics in battle and undeniable ambition for higher office provided opportunities for his political opponents to publicly mischaracterize his military achievements and portray him as irrationally prone to violence (Schlesinger, 57). Despite such efforts to undermine his integrity, Jackson was held in high esteem and enjoyed widespread respect among the electorate for his achievements. Taken together with his personal character, Jacksons elegant white hair and sharp commanding eyes contributed to his public persona as a noble, impressive figure capable of leading the nation (Cheathem, 283). Jackson was known for possessing firm opinions, yet when he was convinced of his error, he politely accepted. Thomas Benton, a close friend and adviser once said, No man knew better the difference between firmness and obstinacy (Cheathem, 276). In fact, Jackson had so much respect for men who differed from him that he appointed several cabinet members who held radically different opinions to foster debate. Martin Van Buren once observed Jackson ranting about an issue in front of a group of visitors and wrote later, This is one of numerous instances...in which I observed a similar contradiction between his apparent undue excitement and his real coolness and selfpossession (Schlesinger, 38). Jacksons strong external character and his personal integritykey measures of greatness according to Gergenprovided Jackson with the widespread respect he needed to accomplish his goals.

From Jacksons first day in office, his leadership and confidence gained steadily, and again, according to Gergen, one sure sign of a successful presidency is the ability to achieve a smooth and effective start. Coming into office with widespread respect as a military hero, the public yearned for a strong leader and a sense of assurance that the country was moving in the right direction. Early on, Jackson convinced the public that he needed to restructure the bureaucracy because the old governing class had maintained control for far too long. He dismissed nearly one-fifth of all federal employees and replaced them with political appointees from his own party (Lindsey, 73). Today, political patronage today is known as the spoils system, and is viewed as corrupt because the job appointment process does not foster competitive hiring practices. In addition, such patronage appointments often result in under-qualified individuals gaining high-level positions with inadequate experience. However, in Jacksons time, the opposite was true and at the time of his election, the federal government was frequently characterized by incompetence and a lack of accountability. Jackson encouraged the growth of the spoils system because he feared that without rotations in office, bureaucratic corruption would continue to spread (Schlesinger, 92). In addition, he saw his individual appointees as not only loyal, but better attuned to the expectations of the electorate and thus likely to be more productive in office. This decision strengthened the Democratic Party and increased the scope of the executive branch. For his cabinet, Jackson selected a number of notable advisers to assist him in addressing the most critical issues facing the nation. For his running-mate, he chose John Calhoun from North Carolina. Calhoun began his term as vice president with a predilection for a strong national government and protective tariffs, but by the end of his term, he transitioned to a position against tariffs and in support of greater states rights (Lindsey,

165). As Calhouns views evolved, his positions were increasingly at odds with Jackson, who eventually dismissed him and sought a new running mate for his second term in office. Martin Van Buren was originally appointed secretary of state, but after Calhouns dismissal, he became vice president (Schlesinger, 56). Throughout their shared time in office, Jackson and Van Buren developed a close and lasting alliance. Van Buren once said of his friend, I have never known a man to whose statements I would more readily trust my own interests, speaking on the issues of the tariff, states rights to nullify federal law and the bank war (Schlesinger, 57). In an attempt to foster diversity of opinion among his advisers, Jackson appointed Edward Livingston as secretary of state after Van Buren. However, Livingston was neither interested in the broad social questions of the time nor did he relish controversy. Jackson remarked, he is a polished scholar, an able writer and a most excellent manbut he knows nothing of mankind (Schlesinger, 82). Livingston was among several Jackson appointees that ultimately proved poorly suited for their jobs, yet the fact that Jackson was willing to accept political and intellectual diversity only underscores his exceptional leadership. Consistent with Gergens identification of strong and prudent advisers as a sign of presidential greatness, as his term progressed, Jackson recognized the need for additional advice on how best to expand economic opportunities for the nations burgeoning population. Sen. Thomas Benton was just the man Jackson needed. Benton was considered one of the best constitutional lawyers in the country and lauded for his extraordinary intellectual abilities (Schlesinger 60) . Benton was a staunch supporter of Jacksons attitude regarding the Bank of the United States. Despite an early disagreement and bar scene brawl over a military appointment by Jackson that prevented Benton from serving on the front

lines of a battle, Benton and Jackson agreed completely on the need to rein in the power of some of the nations leading bankers (Schlesinger 60). While Benton and Jackson were able to set aside their early conflicts and work together to advance the nations interests, other members of Jacksons cabinet were not always able to achieve unity. Marked by petty quarrels and the inability to reach basic agreements, Jacksons first cabinet proved to be an ineffective instrument of executive power (Cole, 106). Recognizing the shortcomings of the federal agency structure, Jackson formed a confidential council known as the Kitchen Cabinet to serve as a group of unofficial advisers. Many believed that Jacksons secret cabinet was filled with the nations brightest scholars; however the two most influential members of the Kitchen Cabinet were journalists. Amos Kendall and Francis Preston Blair were both newspaper editors from The Globe, a national publication (Schlesinger, 74). In addition to benefiting from their knowledge of key issues, Jackson was able to leverage their connections with other media sources to build a powerful propaganda machine and increase his popularity among the general public. This ability to gain the publics endorsement, among the benchmarks Gergen sets forth to define presidential greatness, also enabled Jackson to more effectively secure support for his legislative agenda in Congress. Roger B. Taney, a future Supreme Court judge, was also a member of the Kitchen Cabinet while he served as the secretary of Treasury for Jackson (Schlesinger, 58). Taneys most famous decision as part of the Jackson administration was to order an end to the deposit of federal money in the Second Bank of the United States, which killed the institution (Schlesinger, 58). The development of the revolutionary Kitchen Cabinet, in addition to Jacksons effective use of other capable

advisers, served as a key behind-the-scenes mechanism to ensure a smooth and successful presidency. As Andrew Jacksons administration advanced, three towering national issues emerged: The Bank War, The Nullification Crisis and Native American Removal. Each of these conflicts challenged the leadership of the executive branch and, in retrospect, served as a scale to measure the presidents capacity to persuade Congress. The Bank War in particular was a conflict that solidified the core of the Democratic Party and redefined the powers of the president. The origins of Andrew Jacksons animosity toward the Second Bank of the United States extend back to the period before his first election. During his campaign, Jackson focused significant attention on the need to make the government system more democratic for the working-class male. Coming from a working-class background himself, Jackson feared that any position of power could be easily corrupted unless constraints were set in place to limit that power (Vincent, 133). This personal conviction contributed to Jacksons concerns about the operations of the Second Bank of the United States. Since the government had issued its charter in 1916, the bank had established a virtual monopoly over the currency and complete control over credit and price levels (Lindsey, 197). The bank could neither be taxed by the states, nor could Congress charter any other competing banks. In the eyes of many, the bank was an independent corporation at the level of the state (Schlesinger, 227) Jacksons view was that such a powerful financial institution should not remain independent of the electoral process; it was a disaster waiting to happen. The charter of the Second Bank of the United States was set to expire in 1836, four

years after the next election. Nicholas Biddle, president of the bank, sought to make the conflict an election issue, so that Jackson would have no choice but to support the issue if he wanted to win re-election. Jackson however, had another card to play. While seeming to retreat from the issue, he turned to his confidential Kitchen Cabinet and reached out to sympathetic members of the news media to portray the war against the bank as a war of the common man against the governing elite. Jackson was able to gain sufficient public support on the issue and to Biddles surprise, Jackson retained the presidency for a second term. While Jackson was able to gain support from the people, Congress was not entirely supportive of his intentions. Shortly after Jacksons second election, Congress passed legislation that would extend the charter of the bank, in direct opposition to the presidents stance. By exercising his veto powers, his clear prerogative within the system and an indication of his strength according to Gergen, Jackson declared the bank unconstitutional for a number of reasons: it concentrated the nations financial strength into a single institution, it exposed the government to control by foreign interests and it exercised too much power over members of Congress (Lindsey, 101). The president felt that the bank was intrinsically flawed to the point that it did not merit reform; it was too dangerous and must be destroyed. After Jackson vetoed the extension, he received widespread criticism from both parties as well as from the business community that still remained as a large portion of his constituency. Tocqueville noted, I have practically acquired proof that all enlightened classes are opposed to General Jackson (Schlesinger, 23) Yet once several of Biddles corrupt bribes to public officials were exposed, the bank lost many supporters. In addition, Jackson convened his Kitchen Cabinet and called on Benton in the Senate in an effort to generate support among his colleagues for Jacksons

economic policy. Knowing that they had gained a majority, Treasury Secretary Taney proposed legislation that would prohibit all funds from going to the bank. Thus, Jackson again proved his ability to work with Congress, and in 1834, The Second Bank of the United States was dead (Cheathem, 288). Democrats in Congress rallied behind their leader and resolutions were quickly passed. Without the banks grasp over the economy, Jackson was able to gradually pay off the entire national debt by 1835, making significant progress toward his goal of improving economic opportunity( Schlesinger, 94). In the end, Jacksons war on the bank left three indelible marks on the executive branch. His actions firmly established that the heads of all departments of the government were direct agents responsible to the president, in effect becoming the nations first true chief executive officer. Secondly, Jacksons ability to constructively wield his authority secured the power of the executive branch as equal to that of Congress. Finally, Jackson expanded the presidents influence over the citizenry as a single, nationally elected spokesman (Wall, 196). Through the Bank War, Jackson brought together diverse factions and transformed them into a unified base for the Democratic Party, thus establishing a powerful governing authority for the next decade. While the Bank War still raged, the Nullification Crises erupted in South Carolina. The conflict began in 1828 when Congress passed a protective tax designed to safeguard industry in the United States. Northern manufacturers wanted a protective tax to ensure exclusive access to the domestic market (Boucher, 28). Many Americans favored the idea because it would strengthen the American economy while limiting the U.S. market share of England, still a hostile country at the time. However, some Americans were strongly opposed to the measure as well. Since the major portion of the Souths crops was exported,

the Souths economic livelihood was dependent on foreign markets for products such as cotton, tobacco and rice (Houston, 6). Southern development interests centered on the ability to sell crops for top dollar in foreign markets, then buy manufactured goods from Europe for as cheaply as possible. The tariff put such a high tax on British imports that Southerners were forced to buy more expensive products from the North. In addition, the tariff made it difficult for the British to pay for the cotton they imported from the South. The tariff devastated the Southern economy because it forced the South to sell its commodities at lower prices, while at the same time, pay more for manufactured goods. In response, South Carolina nullified the tariff, calling it unconstitutional. Jackson was put into a difficult position on the tariff issue. While he remained a strong supporter of liberty and of states rights, he also was obligated to preserve the union and enforce the laws. Instead of siding with one argument, Jackson successfully straddled the issue for nearly two years, and remained silent whenever he was able to do so. When pressed with the question, Jackson would often use vague language to avoid a direct response, yet still maintain public support. He once said, The Union, next to state sovereignty must always be preserved (Boucher 171). However, in 1832, the issue of nullification demanded a more specific response from the president as violence was drawing near. Jackson issued a proclamation to South Carolina, considered one of the greatest state papers produced by any American president. In the proclamation, Jackson expressed sympathy with Southerners fears, interests and pride, yet also rejected nullification and state secession by writing, to say that any State may at pleasure secede from the Union is to say the United States is not a nation (Houston, 140). Jacksons proclamation evoked patriotic support from all parts of the country, yet

South Carolina nullifiers showed no sign of weakening. Jackson had no other choice but to propose the Force Bill, which authorized the use of military force to suppress the resistance laws (Houston, 159). At the same time Henry Clay, one of Jacksons political opponents, created a peaceful resolution that would gradually reduce the protection tax annually until it reached the level of 20 percent (David, 277). After Congressional approval for both bills, Jackson signed thema move that not only preserved the union but also served his purpose of protecting the interests of working-class farmers. When the South Carolina convention reconvened, the delegation repealed its nullification ordinance on the tariff but nullified the Force Bill, a meaningless gesture made to maintain the face of state sovereignty (Lindsey, 138). In practical terms, the nullifiers had achieved their goal: to get the protective tariff reduced. Yet on the larger issues, Jackson had prevailed. He had preserved the Union and put in place measures to ensure that federal laws would be obeyed by people in all of the states. Politically, Jackson secured greater control for the Democratic Party throughout government and won followers thanks to his appeals to patriotism. Today, Andrew Jackson often is portrayed as an admirable president due to his tremendous military success, his success in reining in the arrogant bankers and his ability to preserve the United States in the midst of threats of secession. Yet, in analyzing Jacksons legacy from a modern perspective, it is impossible to overlook the tragic impact of his Indian Removal Policy. Among Jacksons own contemporaries, the forced relocation of Native Americans living in the Oklahoma region was considered a necessary and successful effort to ensure greater economic opportunity for white settlers along the nations western frontier. At the time, the president welcomed the support and encouragement of the public as well as Congress to remove Indians from their historic lands. In todays terms however,

Jacksons policies amounted to genocide due to the mass deaths resulting from disease and starvation. Any modern assessment of Jacksons legacy must take into account these conflicting perspectives. As a result of Jacksons policies, the Union was strengthened once again and the push for territorial expansion gained new momentum. The Indians, as the original occupiers of the land, were viewed by most Americans in the early nineteenth century as uncivilized savages who stood in the way of American progress. Most Indians in the south central territorial region were still nomadic hunters and fishers and farming played a very small role in their lives (Cave, 1342). In contrast, most Americans considered farming one of the greatest pursuits of man; therefore a failure to work the land to achieve its potential was considered wasteful. The general conviction was that Indians stood as an obstacle to progress on the American frontier and they needed to go. For his part, Jackson considered the practice of dealing with Indian tribes as independent nations foolish and unrealistic. John C. Calhoun proposed policies that would persuade Eastern Indians to move to lands west of the Mississippi since this land was thought to be unfit for agriculture; and appropriate for Indian occupation (Cave, 1351). A year after Jackson was elected to his first term as president; he made a statement to Congress regarding Indian Removal: This emigration should be voluntary, for it would be as cruel as unjust to compel the aborigines to abandon the graves of their fathers and seek a home in a distant land. But they should be distinctly informed that if they remain within the limits of the States they must be subject to their laws. In return for their obedience as

individuals they will without doubt be protected in the enjoyment of those possessions which they have improved by their industry (Remini, 45). Yet Jackson was pressured by campaign promises to the South for territorial expansion as well as his primary concern for the safety and integrity of the American people. After encountering hostile Indian tribes and the frontier wars on the borders, Jackson came to the conclusion that conflict was inevitable unless a removal policy was passed. To formulate such a policy, Jackson appointed John Eaton of Tennessee as secretary of war, and John Berrien of Georgia as attorney general (Schlesinger, 65). These two men, familiar with Indian tribes in their home regions, drafted the Indian Removal Act, which passed Congress in 1830. The act authorized the president to negotiate treaties and to buy tribal lands in the east in exchange for promised lands west of the Mississippi. In principle, this act offered security to Native Americans that they would have been unlikely to receive otherwise. In practice however, the actual removals resulted in numerous horrors, known today as the Trail of Tears. While some Indian tribes gladly accepted money in exchange for relocation, other tribes did not (Cheatham, 266). The Indian Removal Act explicitly stated that emigration should be voluntary, so if a tribe did not consent to a mass departure, they were not required to leave. Yet as more settlers started to find gold in Indian Territory, Jackson received more demands to remove Indians from their land quickly. Unfortunately, the results ultimately included bribery, military force and an abandonment of nearly every portion of the Indian Removal Act that may have been supportive of the tribes. To cite one example, when Jacksons representatives in Georgia were negotiating with the Cherokee Indians, a group of Indians agreed to the Treaty of New Echota. However, these Indian were not recognized as tribal leaders of the Cherokee Nation

and therefore the treaty was rejected by most Cherokees as illegitimate. The Cherokees then signed a petition of protest to the removal, but it never made its way to the president or Congress. Jackson authorized military force for the removal and it resulted in the deaths of more than 4,000 Cherokee Indians (Lindesy, 142). When Jackson left office, he honestly believed that he had found a safe haven for thousands of Indians to live west of the Mississippi. Today, Jacksons actions are considered to be the epitome of Americas hostility to Native Americans. Yet many people like Jackson supported removal as the most humanitarian means of preserving life and culture, and realistically, no other policy would have been feasible to protect the Native Americans given the white settlers growing firepower (Wall, 191). At the time, Jackson completed precisely what he promised to accomplish in his presidency: territorial expansion and new economic opportunity. While the forced removal policies helped secured Jacksons positive legacy in his day, as generations have passed and morals have changed, Americans have altered the way they look at Jacksons presidency. Andrew Jackson was one of the most influential presidents of the 19th century and had a profound impact on American life and political culture. Through his policies related to territorial expansion, his ability to overcome entrenched and corrupt political powers of the day and his contributions to broadening the economic opportunities for average citizens, Jackson strengthened the role of the executive branch and solidified the base of the Democratic Party. After a careful analysis of seven key criteria, and a thorough review of some troubling aspects of his legacy, the Jackson presidency merits the definition of great.

Works Cited 1. Boucher, Chauncey Samuel. The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina,. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 1916. Print. 2. Cave, Alfred A. "Abuse Of Power: Andrew Jackson And The Indian Removal Act Of 1830." The Historian 65.6 (2003): 1330-353. 3. Cheathem, Mark Renfred. ""The High Minded Honourable Man": Honor, Kinship, and Conflict in the Life of Andrew Jackson Donelson." Journal of the Early Republic 27.2 (2007): 265-92. 4. Cole, Donald B. Vindicating Andrew Jackson: The 1828 Election and the Rise of the Twoparty System. Lawrence: University of Kansas, 2009. Print. 5. Houston, David Franklin. Critical Study of Nullification in South Carolina. London: Cambridge Harvard UP, 2009. Print. 6. Lindsey, David. Andrew Jackson & John C. Calhoun. Woodbury, NY: Barron's Educational Series, 1973. Print. 7. Remini, Robert Vincent. The Legacy of Andrew Jackson: Essays on Democracy, Indian Removal, and Slavery. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1988. Print. 8. Schlesinger Jr., Arthur M. The Age of Jackson. Boston: Little, Brown and, 1945. Print. 9. Wall, David. "Andrew Jackson Downing and the Tyranny of Taste." American Nineteenth Century History 8.2 (2007): 187-203.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Static GK in EnglishDocument39 pagesStatic GK in EnglishAarav Singh100% (2)

- 09 Constitutional Development 1949-56Document17 pages09 Constitutional Development 1949-56asiya raniPas encore d'évaluation

- Format of The MemorialDocument3 pagesFormat of The MemorialJohnPaulRomeroPas encore d'évaluation

- Majority Rule and Minority ProtectionDocument6 pagesMajority Rule and Minority ProtectionSargam KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Notice To Members: European ParliamentDocument2 pagesNotice To Members: European Parliamentdjsonja07Pas encore d'évaluation

- NCGR Vol I-1Document347 pagesNCGR Vol I-1Atta U LlahPas encore d'évaluation

- Tanada vs. AngaraDocument3 pagesTanada vs. AngaraKGTorresPas encore d'évaluation

- 03-17-10 Doc 53 - Motion For Stay Pending AppealDocument15 pages03-17-10 Doc 53 - Motion For Stay Pending AppealWashington ExaminerPas encore d'évaluation

- Spls For Bar 2019Document23 pagesSpls For Bar 2019Mitchi BarrancoPas encore d'évaluation

- Kabwum Elites Meeting1 - 13Document3 pagesKabwum Elites Meeting1 - 13ddpion2511Pas encore d'évaluation

- San Miguel Vs San MiguelDocument3 pagesSan Miguel Vs San MiguelRZ ZamoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Legal Method MidtermsDocument24 pagesLegal Method MidtermsAngel Valencia EspejoPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter - 05 Political Science Panchayati RajDocument1 pageChapter - 05 Political Science Panchayati RajSwapnil ChaudhariPas encore d'évaluation

- Iim Rohtak Model United Nations 2020: All India Political Parties MeetDocument21 pagesIim Rohtak Model United Nations 2020: All India Political Parties MeetANKUR PUROHITPas encore d'évaluation

- Tobias Vs Abalos 239 SCRA 106Document3 pagesTobias Vs Abalos 239 SCRA 106Aiyla AnonasPas encore d'évaluation

- Ibps Clerks Prelims 1 2022Document12 pagesIbps Clerks Prelims 1 2022NavyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Force Jan. 27, 1980.: Vienna Convention On The Law of Treaties, 1155 U.N.T.S. 331, 8 I.L.M. 679, Entered IntoDocument39 pagesForce Jan. 27, 1980.: Vienna Convention On The Law of Treaties, 1155 U.N.T.S. 331, 8 I.L.M. 679, Entered IntoPrince Joyous LisingPas encore d'évaluation

- IPRA Law - Case DigestDocument1 pageIPRA Law - Case DigestVicelle QuilantangPas encore d'évaluation

- Facts:: Sed Lex. The Law May Be Harsh But That Is The Law. ThereforeDocument12 pagesFacts:: Sed Lex. The Law May Be Harsh But That Is The Law. ThereforeAnne DerramasPas encore d'évaluation

- Titles To PropertyDocument17 pagesTitles To PropertyjpesPas encore d'évaluation

- Kenya Supreme Court Justice Njoki Ndung'u's Dissenting VerdictDocument4 pagesKenya Supreme Court Justice Njoki Ndung'u's Dissenting VerdictThe Independent MagazinePas encore d'évaluation

- Korea 1950Document297 pagesKorea 1950Bob Andrepont100% (6)

- His Majesty's Declaration of Abdication Act 1936Document3 pagesHis Majesty's Declaration of Abdication Act 1936HRPas encore d'évaluation

- Abroginal Land RightsDocument11 pagesAbroginal Land RightsScott SheppardPas encore d'évaluation

- A. Parliamentary Government and Presidential GovernmentDocument18 pagesA. Parliamentary Government and Presidential GovernmentDeadly ChillerPas encore d'évaluation

- Persuasive Essay Draft 1Document11 pagesPersuasive Essay Draft 1mstreeter1124Pas encore d'évaluation

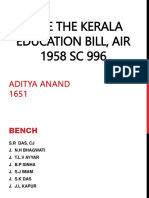

- In Re The Kerala Education Bill, Air 1958 SC 996: Aditya Anand 1651Document11 pagesIn Re The Kerala Education Bill, Air 1958 SC 996: Aditya Anand 1651Aditya AnandPas encore d'évaluation

- Ap Virginia Plan Give To Much Power..Document2 pagesAp Virginia Plan Give To Much Power..maxterofsoccerPas encore d'évaluation

- Meteoro V Creative CreaturesDocument2 pagesMeteoro V Creative CreaturesCastle Castellano100% (2)

- 15 Republic Vs ReyesDocument3 pages15 Republic Vs ReyesEAPas encore d'évaluation