Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Backup of Obligations Finals Outline-RHILL (2012)

Transféré par

roneekahDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Backup of Obligations Finals Outline-RHILL (2012)

Transféré par

roneekahDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

General Principles of Obligations/Sources of Obligations Art. 1756.

definition Obligations; An obligation is a legal relationship whereby a person, called the obligor, is bound to render a performance in favor of another, called the obligee. Performance may consist of giving, doing, or not doing something. Sources of Obligations arise from contracts and other declarations of will. They also arise directly from the law, regardless of a declaration of will, in instances such as wrongful acts, the management of the affairs of another, unjust enrichment and other acts or facts. A. An obligation may give the obligee the right to: (1) Enforce the performance that the obligor is bound to render; (2) Enforce performance by causing it to be rendered by another at the obligor's expense; (3) Recover damages for the obligor's failure to perform, or his defective or delayed performance. B. An obligation may give the obligor the right to: (1) Obtain the proper discharge when he has performed in full; (2) Contest the obligee's actions when the obligation has been extinguished or modified by a legal cause. Art. 1759. Good faith Good faith shall govern the conduct of the obligor and the obligee in whatever pertains to the obligation.

Art. 1757. obligations

Art. 1758. General effects

Art. 1760. Moral duties that A natural obligation arises from circumstances in which the may give rise to a natural law implies a particular moral duty to render a performance. obligation Art. 1786. Several, joint, and When an obligation binds more than one obligor to one obligee, or binds one obligor to more than one obligee, or solidary obligations binds more than one obligor to more than one obligee, the obligation may be several, joint, or solidary. Art. 1787. Several When each of different obligors owes a separate performance

obligations; effects

to one obligee, the obligation is several for the obligors. When one obligor owes a separate performance to each of different obligees, the obligation is several for the obligees. A several obligation produces the same effects as a separate obligation owed to each obligee by an obligor or by each obligor to an obligee.

Art. 1788. Joint obligations When different obligors owe together just one performance to one obligee, but neither is bound for the whole, the for obligors or obligees obligation is joint for the obligors. When one obligor owes just one performance intended for the common benefit of different obligees, neither of whom is entitled to the whole performance, the obligation is joint for the obligees. Art. 1789. Divisible and When a joint obligation is divisible, each joint obligor is bound to perform, and each joint obligee is entitled to indivisible joint obligation receive, only his portion. When a joint obligation is indivisible, joint obligors or obligees are subject to the rules governing solidary obligors or solidary obligees. Art. 1971. Freedom of parties Art. 1972. Possible impossible object Parties are free to contract for any object that is lawful, possible, and determined or determinable.

or A contractual object is possible or impossible according to its own nature and not according to the parties' ability to perform.

NOTE---2315? Art. 3182. Debtor's general Whoever has bound himself personally, is obliged to fulfill his engagements out of all his property, movable and liability. immovable, present and future. Art. 3183. Debtor's property common pledge of creditors; exceptions to pro rata distribution. General Principles The property of the debtor is the common pledge of his creditors, and the proceeds of its sale must be distributed among them ratably, unless there exist among the creditors some lawful causes of preference.

Sources of Obligations

Every obligation contains a duty, as a necessary element, but not every duty amounts to an obligation There is in every obligation an active subject, the creditor or oblige, to whom the right to demand performance belongs, and a passive subject, the debtor or obligor, who is under the duty to perform Classifications of Obligations o obligation to give obligor binds himself to transfer to the oblige the ownership of a thing o obligation to do obligor binds himself to carry out or execute an act o obligation not to do obligor binds himself to abstain from undertaking a certain course of action insert real rights credit rights, etc

4 Sources of Obligations o Contracts, quasi-contracts, delcits, and quasi-delicts o Contracts Willful and lawful acts whereby persons agree to bind themselves by obligations o Quasi-contracts Willful and lawful acts also Give rise to obligations without the concurrence of wills without the agreement of the persons involved that is necessary for the formation of a contract o Delicts and Quasi-Delicts Unlawful acts that cause damage Harrison v. Gore o When a student is molested and sexually harassed by a former coach and the alleged act occurred 8 years before the institution of a suit, the nature of the duty breached determines whether the action is in tort or in contract. If in tort, a one year prescriptive period applies and 10 years if in contract

Capacity Art. 1918. General All persons have capacity to contract, except unemancipated minors, interdicts, and persons deprived of reason at the time of statement of capacity contracting. Art. 1919. Right to plead A contract made by a person without legal capacity is relatively null and may be rescinded only at the request of that person or his rescission legal representative. Art. 1920. Right to require Immediately after discovering the incapacity, a party, who at the confirmation or rescission time of contracting was ignorant of the incapacity of the other

of the contract

party, may require from that party, if the incapacity has ceased, or from the legal representative if it has not, that the contract be confirmed or rescinded.

Art. 1921. Rescission of Upon rescission of a contract on the ground of incapacity, each party or his legal representative shall restore to the other what he contract for incapacity has received thereunder. When restoration is impossible or impracticable, the court may award compensation to the party to whom restoration cannot be made. Art. 1922. emancipated minor Fully A fully emancipated minor has full contractual capacity.

Art. 1923. Incapacity of A contract by an unemancipated minor may be rescinded on unemancipated minor; grounds of incapacity except when made for the purpose of providing the minor with something necessary for his support or exceptions education, or for a purpose related to his business. Art. 1924. Mere The mere representation of majority by an unemancipated minor representation of majority; does not preclude an action for rescission of the contract. When the other party reasonably relies on the minor's representation of reliance majority, the contract may not be rescinded. Art. 1925. Noninterdicted person deprived of reason; protection of innocent contracting party by onerous title A noninterdicted person, who was deprived of reason at the time of contracting, may obtain rescission of an onerous contract upon the ground of incapacity only upon showing that the other party knew or should have known that person's incapacity.

Art. 1926. Attack on A contract made by a noninterdicted person deprived of reason at noninterdicted decedent's the time of contracting may be attacked after his death, on the ground of incapacity, only when the contract is gratuitous, or it contracts evidences lack of understanding, or was made within thirty days of his death, or when application for interdiction was filed before his death.

General Principles Four Fundamental Prerequisites for the existence of a contract o Capacity

o Cause o Consent o Object Contractual Capacity o The ability to exercise certain rights and duties Insert Rabin case pg. 19

Consent Union of Parties Will Art. 1927. Consent A contract is formed by the consent of the parties established through offer and acceptance. Unless the law prescribes a certain formality for the intended contract, offer and acceptance may be made orally, in writing, or by action or inaction that under the circumstances is clearly indicative of consent. Unless otherwise specified in the offer, there need not be conformity between the manner in which the offer is made and the manner in which the acceptance is made. Art. 1936. Reasonableness A medium or a manner of acceptance is reasonable if it is the of manner and medium of one used in making the offer or one customary in similar transactions at the time and place the offer is received, unless acceptance circumstances known to the offeree indicate otherwise. Art. 1939. Acceptance by When an offeror invites an offeree to accept by performance and, according to usage or the nature or the terms of the performance contract, it is contemplated that the performance will be completed if commenced, a contract is formed when the offeree begins the requested performance.

Belgard v. Collins

Expressing Consent Art. 1942. Acceptance by silence When, because of special circumstances, the offeree's silence leads the offeror reasonably to believe that a contract has been formed, the offer is deemed accepted.

Art. 2687. Damage caused by The lessee is liable for damage to the thing caused by his

fault

fault or that of a person who, with his consent, is on the premises or uses the thing.

Art. 2688. Obligation to inform The lessee is bound to notify the lessor without delay when the thing has been damaged or requires repair, or when his lessor possession has been disturbed by a third person. The lessor is entitled to damages sustained as a result of the lessee's failure to perform this obligation. Art. 2689. Payment of taxes and The lessor is bound to pay all taxes, assessments, and other charges that burden the thing, except those that arise from other charges the use of the thing by the lessee. North Louisiana Milk Producers Assoc. v. Southland Corporation Illinois Central Gulf Railroad Company v. International Harvester Company Marine Insurance Company Limited of London, England v. Rehm Cashio v. Amco Transmissions

The offer/Duration of the offer Art. 1928. Irrevocable offer An offer that specifies a period of time for acceptance is irrevocable during that time.

When the offeror manifests an intent to give the offeree a delay within which to accept, without specifying a time, the offer is irrevocable for a reasonable time. Art. 1929. Expiration of irrevocable offer An irrevocable offer expires if not accepted within the time prescribed in the preceding for lack of acceptance Article. Art. 1930. Revocable offer An offer not irrevocable under Civil Code Article 1928 may be revoked before it is accepted. A revocable offer expires if not accepted within a reasonable time.

Art. 1931. Expiration of revocable offer

Art. 1932. Expiration of offer by death or An offer expires by the death or incapacity of the offeror or the offeree before it has incapacity of either party been accepted. Offer o A unilateral declaration of will that a person-the offeror- addresses to another- the offeree- whereby the former proposes to the latter the conclusion of a contract

The offerors will must be declared- projected outward- otherwise the offeree would not be apprised of the offerors intent The declaration must be addressed to the person with whom the offeror intends to contract Must be sufficiently precise and complete so that the intended contract can be concluded by the offerees expression of his own assent If a lease- the offer must be sufficiently precise concerning the thing which is the contractural object o An offer may be made to any one person in particular or to several persons o An offer may also be made to the public at large through proper means of communication o An offer may be made by words spoken Offers to the public, Advertisements, and Invitations to Negotiate o A true offer is accompanined by the offerors intent to bind himself upon the offerees acceptance o An offer made by advertisement is not a true offer but an invitation to make offers o In the absence of special circumstances, ad proposing a contract such as the announcement that certain goods are for sale at a certain price shoueld be regarded in LA as an invitation to negotiate rather than a true offer Johnson v Capital City Ford Co. Inc. o When a car dealer places a newspaper advertisement to lure customers onto his lot and the wording used in the advertisement is specific to the offer; the offeror is bound by the obligation previously offered by him in exchange for the act which the obligee has performed in response to the offer. North Central Utilities, Inc. v Walker Comm Water System, Inc. o Requests for bids are considered only as invitations to others to make offers. For a proposal to constitute an offer, it must firmly reflect the intent of the author to enter into a contract

Duration of the Offer Duration o Proposition to enter into a contract is not intended to remain open indefinitely or for an unreasonably long period of time o When no period of time has been named then if the parties are at a distance the minimum reasonable period intended for the duration of the offer is the time necessary for the message that contains it to reach the offeree plus the time necessary for the offerees reply to get back to the offeror Schulingkamp v. Aicklen o When an offeror manifests intent to give the offeree a delay within which to accept his offer, without specifying a time, the offer is irrevocable for a reasonable time Meyers v. Burger King Corporation

o When an offer is said to last at least 45 days the court says that that is not a specified period of time and the court will determine a reasonable time which may be beyond that noted period. W.M. Heroman & Co. Inc v. Saia Electric Inc o When a custom prevails in the bldg trade to the effect that a subcontractors bid to a general contractor, in the absence of a provision to the contrary, may be considered irrevocable after it has been used in preparation of the general contractors bid to the owner, and has been accepted by the owner prior to the attempted revocation by the subcontractor.

Irrevocable Offer An offer that specifies a period of time for acceptance is irrevocable during that time In the case where the offeror has manifested an intention to give the offeree a delay within which to accept, though without specifying a time An offeror is bound not to revoke an irrievocable offer but only from he time that offer comes to the knowledge of the offereee which means that before the offeree acquires such knowledge the offeror may revoke his irrevocable offer if he succeeds in overtaking it by revocation sent by a faster means In the other hand, nothing prevents an offeror from qualifying an offer that specifies a times for acceptance by stating that in spite of that specification, the offer is subject to revocation at any time

Revocable Offer An offer may be revoked before it is accepted o When the offeror does not specify aperiod of time for acceptance o When the offeror does ont manifest an intent to give the offeree a delay within which to accept

Liability for Revocation of an Irrevocable Offer When an offer was intended to remain open for either a certain or reasonable period of time, its revocation before that has expired renders the offeror liable without need for the offeree to show the offerors fault, although subject to the latters right to prove the absence of any fault

Offer of Reward to the Public (a) Communication to Offeree An offer of reward made to the public is binding on the offeror regardless of whether the person who performs the requested act knows of the offer. (b) Revocability of Reward Offers An offer of reward made to the public is revocable before completion of performance but can be revoked only by the same or equal means used for the offer.

(c) Performance by more than one person If more than one person has performed the requested act, the reward goes to that person who first gave notice to the offeror of the completion of the performance.

Options Contracts and Rights of First Refusal Art. 1933. Option contracts An option is a contract whereby the parties agree that the offeror is bound by his offer for a specified period of time and that the offeree may accept within that time. An option to buy, or an option to sell, is a contract whereby a party gives to another the right to accept an offer to sell, or to buy, a thing within a stipulated time. An option must set forth the thing and the price, and meet the formal requirements of the sale it contemplates. Art. 2625. Right of first refusal A party may agree that he will not sell a certain thing without first offering it to a certain person. The right given to the latter in such a case is a right of first refusal that may be enforced by specific performance.

Art. 2620. Option to buy or sell

Art. 2626. Terms of offered The grantor of a right of first refusal may not sell to another person unless he has offered to sell the thing to the holder of sale the right on the same terms, or on those specified when the right was granted if the parties have so agreed Art. 2627. Right of first refusal, Unless otherwise agreed, an offer to sell the thing to the holder of a right of first refusal must be accepted within ten time for acceptance days from the time it is received if the thing is movable, and within thirty days from that time if the thing is immovable. Unless the grantor concludes a final sale, or a contract to sell, with a third person within six months, the right of first refusal subsists in the grantee who failed to exercise it when an offer was made to him.

How do options contracts and irrevocable offers differ? (a) Option Contracts o is a contract

o does not expire at death o can be assigned (b) Irrevocable offer o is not a contract o expires at death of either the offeror or the offeree o cannot be assigned Glover v. Abney o says , when alive, created an option contract to sell land within 5 years. If it was an irrevocable offer then there is no agreement (thus no option), only a unilateral declaration of will. To be valid as an option, the instrument must be supported by a valuable consideration. The instrument does not recite a consideration and evidence showed there was no consideration, thus merely a naked promise to sell

Right of First Refusal Movable (Ro1stR)- 10 days to respond to proposal Immovable (Ro1stR)- 30 days to respond to proposal o An option or right cannot be granted for a term longer than ten years o However if an option or right of first refusal may be granted in connection with a contract that provides for continuous or periodic performances such as 20 year lease contract that also provides the lessee with a right of first refusal to purchase the property at the end of the leas, then the option or right may be granted for as long a period of time as required for the performance of the lease Youngblood v. Rosedale Development, LLC

Consent Communciation of Acceptance and Time of Formation Art. 1927. Consent A contract is formed by the consent of the parties established through offer and acceptance. Unless the law prescribes a certain formality for the intended contract, offer and acceptance may be made orally, in writing, or by action or inaction that under the circumstances is clearly indicative of consent. Unless otherwise specified in the offer, there need not be conformity between the manner in which the offer is made and the manner in which the acceptance is made. Art. 1934. Time when acceptance of An acceptance of an irrevocable offer is effective when an irrevocable offer is effective received by the offeror. Art. 1935. Time when acceptance of Unless otherwise specified by the offer or the law, an

a revocable offer is effective

acceptance of a revocable offer, made in a manner and by a medium suggested by the offer or in a reasonable manner and by a reasonable medium, is effective when transmitted by the offeree.

Art. 1936. Reasonableness of manner A medium or a manner of acceptance is reasonable if it is the one used in making the offer or one customary in and medium of acceptance similar transactions at the time and place the offer is received, unless circumstances known to the offeree indicate otherwise. Art. 1937. Time when revocation is A revocation of a revocable offer is effective when effective received by the offeree prior to acceptance. Art. 1938. Reception of revocation, A written revocation, rejection, or acceptance is received when it comes into the possession of the addressee or of a rejection, or acceptance person authorized by him to receive it, or when it is deposited in a place the addressee has indicated as the place for this or similar communications to be deposited for him. Art. 1939. performance Acceptance by When an offeror invites an offeree to accept by performance and, according to usage or the nature or the terms of the contract, it is contemplated that the performance will be completed if commenced, a contract is formed when the offeree begins the requested performance.

Art. 1940. Acceptance only by When, according to usage or the nature of the contract, or its own terms, an offer made to a particular offeree can be completed performance accepted only by rendering a completed performance, the offeror cannot revoke the offer, once the offeree has begun to perform, for the reasonable time necessary to complete the performance. The offeree, however, is not bound to complete the performance he has begun. The offeror's duty of performance is conditional on completion or tender of the requested performance. Art. 1941. Notice of commencement When commencement of the performance either constitutes acceptance or makes the offer irrevocable, the of performance offeree must give prompt notice of that commencement unless the offeror knows or should know that the offeree has begun to perform. An offeree who fails to give the

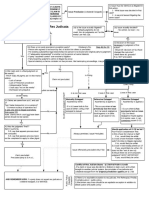

notice is liable for damages. Communciation of Acceptance and Time of Formation Insert chart on mailbox rule Overtaking the Acceptance With a Rejection Should the offeror receive an acceptance and a rejection at the same time it behooves him to check the date of each message in order to ascertain the latest intent of the offeree in compliance with the ovveridding obligation of good faith If the offer is revocable the situation is quite different since the acceptance is then effective upon transmission which means that any later rejection could become effective only after the acceptance has become effective

Overtaking of a Rejection by an Acceptance The solution is the same whether the offer is irrevocable or revocable Irrevocable o Both acceptance and rejection are effective upon receipt by the offeror Revocable o The acceptance is effective upon transmissioun o Rejection is effective only upon receipt Ryder v. Frost Cardinal Wholesale Supply, Inc. v. Chaisson Ambrose v. M & M Dodge, Inc. Evertite Roofing Corporation v. Green National Co. v. Navarro

Acceptance & Terms of Offer Art. 1943. Acceptance not in accordance An acceptance not in accordance with the terms of the offer is deemed to be a with offer counteroffer. Counteroffer A new offer address by an offeree toteh offeror of an original offer involving the same matter and proposing terms that are different from those contained in the original offer

Rejection An expression of the offerees intention not to accept the offer made to him and is effective when received by the offeror

Rodrigue v. Gebhardt

Form Art. 1927. Consent A contract is formed by the consent of the parties established through offer and acceptance. Unless the law prescribes a certain formality for the intended contract, offer and acceptance may be made orally, in writing, or by action or inaction that under the circumstances is clearly indicative of consent. Unless otherwise specified in the offer, there need not be conformity between the manner in which the offer is made and the manner in which the acceptance is made. Art. 1947. Form contemplated When, in the absence of a legal requirement, the parties have contemplated a certain form, it is presumed that they do not by parties intend to be bound until the contract is executed in that form.

Cause

Breaux Brothers Construction Company v. Associated Contractors, Inc. Barchus v. Johnson

Art. 1966. No obligation An obligation cannot exist Ex.- a pre-existing duty (pg. 137) without cause without a lawful cause. -cause may be partially absent; in the case of perishing goodsa party may free himself of the obligation or may accept a reduced obligation Art. 1967. Cause defined; Cause is the reason why a The consideration or motive for detrimental reliance party obligates himself. making a contract A party may be obligated by a promise when he knew or should have known that the promise would induce the other party to rely on it to his detriment and the other party was reasonable in so relying.

Recovery may be limited to the expenses incurred or the damages suffered as a result of the promisee's reliance on the promise. Reliance on a gratuitous promise made without required formalities is not reasonable. Art. 1968. Unlawful cause The cause of an obligation is unlawful when the enforcement of the obligation would produce a result prohibited by law or against public policy. -immoral cause-when the cause runs counter to the moral standards of the community -it is against public policy when it is contrary to values recognized as paramount by the community

Art. 1969. expressed

Cause

not An obligation may be valid even though its cause is not expressed.

Art. 1970. Untrue expression When the expression of a cause in a contractual of cause obligation is untrue, the obligation is still effective if a valid cause can be shown.

Cause as a Criterion for Classification of Contracts Art. 1906. contract Definition of A contract is an agreement by two or more parties whereby obligations are created, modified, or extinguished.

Art. 1907. contracts

Unilateral A contract is unilateral when the party who accepts the obligation of the other does not assume a reciprocal obligation. or A contract is bilateral, or synallagmatic, when the parties obligate themselves

Art. 1908. Bilateral synallagmatic contracts

reciprocally, so that the obligation of each party is correlative to the obligation of the other. Art. 1909. Onerous contracts A contract is onerous when each of the parties obtains an advantage in exchange for his obligation. -an act which as a donation is invalid for the lack of proper form may be however a valid onerous contract -charitable subscription considered to be onerous contractinvalid if not under authentic act Art. 1910. contracts Gratuitous A contract is gratuitous when one party obligates himself towards another for the benefit of the latter, without obtaining any advantage in return. Commutative A contract is commutative when the performance of the obligation of each party is correlative to the performance of the other. A contract is aleatory when, because of its nature or according to the parties' intent, the performance of either party's obligation, or the extent of the performance, depends on an uncertain event.

Art. 1911. contracts

Art. 1912. Aleatory contracts

Art. 1913. Principal accessory contracts

and A contract is accessory when it is made to provide security for the performance of an obligation. Suretyship, mortgage, pledge, and other types of security agreements are examples of such a contract. When the secured obligation arises from a contract, either between the same or other parties, that contract is the

principal contract. Art. 1914. Nominate and Nominate contracts are those given a special designation innominate contracts such as sale, lease, loan, or insurance. Innominate contracts are those with no special designation Art. 1915. Rules applicable to All contracts, nominate and innominate, are subject to the all contracts rules of this title Art. 1916. Rules applicable to Nominate contracts are subject to the special rules of the nominate contracts respective titles when those rules modify, complement, or depart from the rules of this title. Art. 1917. Rules applicable to The rules of this title are applicable also to obligations all kinds of obligations that arise from sources other than contract to the extent that those rules are compatible with the nature of those obligations. Art. 1526. Onerous donation The rules peculiar to donations inter vivos do not apply to a donation that is burdened with an obligation imposed on the donee that results in a material advantage to the donor, unless at the time of the donation the cost of performing the obligation is less than twothirds of the value of the thing donated.

Art. 1527. donations

Remunerative The rules peculiar to donations inter vivos do not apply to a donation that is made to recompense for services rendered that are susceptible of being measured in money unless at the time of the

donation the value of the services is less than two-thirds of the value of the thing donated. Art. 1528. Charges or The donor may impose on the donee any charges or conditions imposed by donor conditions he pleases, provided they contain nothing contrary to law or good morals. Art. 1529. Donation of future A donation inter vivos can have as its object only present property; nullity property of the donor. If it includes future property, it shall be null with regard to that property. Art. 1530. Donation A donation inter vivos is null conditional on will of donor; when it is made on a condition the fulfillment of which nullity depends solely on the will of the donor. Art. 1531. Donation conditional on payment of future or unexpressed debts and charges; nullity A donation is also null if it is burdened with an obligation imposed on the donee to pay debts and charges other than those that exist at the time of the donation, unless the debts and charges are expressed in the act of donation.

Art. 1532. Stipulation for The donor may stipulate the right of return of the thing right of return to donor given, either in the case of his surviving the donee only, or in the case of his surviving the donee and the descendants of the donee. The right may be stipulated only for the advantage of the donor.

Art. 1533. Right of return; The effect of the right of return is that the thing donated effect returns to the donor free of any alienation, lease, or encumbrance made by the donee or his successors after the donation. The right of return shall not apply, however, to a good faith transferee for value of the thing donated. In such a case, the donee and his successors by gratuitous title are, nevertheless, accountable for the loss sustained by the donor. Art. 1467. Methods of Property can neither be acquiring or disposing acquired nor disposed of gratuitously except by gratuitously donations inter vivos or mortis causa, made in one of the forms hereafter established. Art. 1468. Donations inter A donation inter vivos is a contract by which a person, vivos; definition called the donor, gratuitously divests himself, at present and irrevocably, of the thing given in favor of another, called the donee, who accepts it. Art. 1469. Donation mortis A donation mortis causa is an act to take effect at the death causa; definition of the donor by which he disposes of the whole or a part of his property. A donation mortis causa is revocable during the lifetime of the donor. Art. 1493. Forced heirs; A. Forced heirs are representation of forced heirs descendants of the first degree who, at the time of the death of the decedent, are twenty-three years of age or younger or

descendants of the first degree of any age who, because of mental incapacity or physical infirmity, are permanently incapable of taking care of their persons or administering their estates at the time of the death of the decedent. B. When a descendant of the first degree predeceases the decedent, representation takes place for purposes of forced heirship only if the descendant of the first degree would have been twenty-three years of age or younger at the time of the decedent's death. C. However, when a descendant of the first degree predeceases the decedent, representation takes place in favor of any child of the descendant of the first degree, if the child of the descendant of the first degree, because of mental incapacity or physical infirmity, is permanently incapable of taking care of his or her person or administering his or her estate at the time of the decedent's death, regardless of the age of the descendant of the first degree at the time of the decedent's death. D. For purposes Article, a person is three years of age or until he attains the twenty-four years. of this twentyyounger age of

E. For purposes of this Article "permanently incapable of taking care of their persons or

administering their estates at the time of the death of the decedent" shall include descendants who, at the time of death of the decedent, have, according to medical documentation, an inherited, incurable disease or condition that may render them incapable of caring for their persons or administering their estates in the future. Art. 1494. Forced heir A forced heir may not be entitled to legitime; exception deprived of the portion of the decedent's estate reserved to him by law, called the legitime, unless the decedent has just cause to disinherit him. Art. 1570. Testaments; form A disposition mortis causa may be made only in the form of a testament authorized by law.

Art. 1571. Testaments with A testament may not be others or by others prohibited executed by a mandatary for the testator. Nor may more than one person execute a testament in the same instrument. Art. 2891. definition Loan for use; The loan for use is a gratuitous contract by which a person, the lender, delivers a nonconsumable thing to another, the borrower, for him to use and return.

Art. 2892. Applicability of In all matters for which no the rules governing special provision is made in this Title, the contract of loan obligations for use is governed by the Titles of "Obligations in

General" and "Conventional Obligations or Contracts". Art. 2893. Things that may be Any nonconsumable thing that is susceptible of ownership lent may be the object of a loan for use. Art. 2894. Preservation and The borrower is bound to keep, preserve, and use the limited use thing lent as a prudent administrator. He may use it only according to its nature or as provided in the contract. Art. 2926. Deposit; definition A deposit is a contract by which a person, the depositor, delivers a movable thing to another person, the depositary, for safekeeping under the obligation of returning it to the depositor upon demand.

Art. 2929. Formation of the The formation of a contract of deposit requires, besides an contract; delivery agreement, the delivery of the thing to the depositary. Art. 2995. Incidental, The mandatary may perform necessary, or professional acts all acts that are incidental to or necessary for the performance of the mandate. The authority granted to a mandatary to perform an act that is an ordinary part of his profession or calling, or an act that follows from the nature of his profession or calling, need not be specified. Art. 2992. Onerous gratuitous contract or The contract of mandate may be either onerous or gratuitous. It is gratuitous in the absence

of contrary agreement.

Invalid Gratuitous Contract but Valid Onerous Contract o an act which, as a donation, is invalid for the lack of proper form may be however, a valid onerous contract. o If a manual gist is made of a promissory note signed by the donor, the donation is invalid because, the note is an incorporeal thing, a donation thereof must be made by authentic act. o If note was not given with donative intent but as recompense for services rendered in the past by the one to whose order the note is made, or in fulfillment of a natural obligation, then the giving of the promissory note, though an invalid donation, is classified as a valid onerous contract. o Charitable subscriptions are gratuitous acts and therefore invalid if made by writing under private signature rather than by an authentic act. Nevertheless, since the satisfaction of some interest such as the promotion of the arts or education can be the reason that prompts one to make a charitable subscription, this will suffice to conclude that a charitable subscription not made in authentic form is an enforceable onerous contract. Invalid Onerous Contract but Valid Gratuitous Contract o If no price in a sale is paid, because the parties never intended for the price to be paid, that onerous contract is invalid for the lack of one of its requirements. o If an intention to donate immovable property results from the circumstances, and the invalid sale was made by authentic act, the invalid onerous contract is a valid donation. Invalid Onerous Contract and Invalid Gratuitous Contract An apparently onerous contract that is invalid for a lack of cause in the obligation on one party may not be a valid gratuitous contract, in spite of the existence of a donative intent, if the requirement of form has not been met. o When a promissory note is given for an alleged loan but it is proved such loan was never made and that the maker of the note actually intended to make a gift to the alleged lender, no valid donation can be found if the act was not made by an authentic act. Donations Inter Vivos donations given while one is living o 1) Types of donations inter vivos (a) Purely gratuitous made without conditions, merely from liberality (b) Onerous burdened with charges imposed on the donee; NOT a real donation, if the value of the object give does not manifestly exceed that of the charges impose on the donee, because then you are not bestowing a liberality. o (c) Remunerative to recompense for services rendered;

NOT a real donation, if the value of the services to be recompensed thereby being appreciated in money, should be little inferior to that of the gift; Remunerative donations usually involve familial or close relationships whereas natural obligations, such as fulfillment of past debts do not. Onerous and remunerative donations are not subject to the rules and peculiar to donations inter vivos, except when the value of the object given exceeds by that of the charges or of the services Spanier v DeVoe Donation of immovable property Instead of having a notary and 2 witnesses, had the commissioner sign as a private person. A price which is out of all proportion with the value of the thing sold invalidates the sale, and that such a contract is a donation improperly called a sale. An act under private signature, though acknowledged, cannot substitute for an authentic act when the law prescribes such an act. The only exception to authentic form for donations is the donations of incorporeal movables such as negotiable instruments (savings certificates and stock transfers) Succession of Lawrence - When a nephew has helped his uncle for 35 years doing various acts of manual labor and they are very close and the uncle desires to leave his money to his nephew and manifests his intent to donate by opening a joint bank account and the testament which he had notarized indicating simply and without elaboration that he wanted his nephew to have his property, the gift of the money constituted a donation inter vivos remunerative and onerous donations since the value of the bank accounts at the time of the uncles death did not exceed by that of the services rendered by the nephew and the charges imposed upon him during the uncles lifetime.

The Manual Gift Article 1539 Money, automobiles, stuffed teddy bear No formality other than delivery is required to make a valid manual gift Indirect Manual Gift Delivery of a sum of money to a third person to acquire property for the donee

Perry v. Perry Theilman v. Gahlman Louisiana College v. Keller (charitable subscriptions) Baptist Hospital v. Cappel Flood v. Thomas (debt of another party)

DOrgenoy v. Droz

Absence of Cause Art. 1966. No obligation An obligation cannot exist If a party binds himself in return for a promise without cause without a lawful cause. the other party was already under a legal duty to perform, the contract is invalid since a promise to perform a pre-existing legal duty which is neither doubtful nor the subject to an honest dispute is not consideration United States Fidelity & Guaranty Co. v. Crais

Failure of Cause 1) 2) A cause may exist at the inception of an obligation and then fail, thus the obligation ceases to exist A cause may fail only in part.

Carpenter v. Williams o (Mention the Ds know. of the cause in prop) Loseco v. Gregory o When a party contracts to purchase all of the oranges a farmers trees are to produce for two years, and an unexpected freeze occurs then the seller is bound to reimburse the purchases because a contract is said to be without cause when the consideration for making it was something which in the contemplation of the parties was thereafter expected to exist or take place, and which did not take place or exist, and, If during the lease the thing be totally destroyed by an unforeseen event the lease is at an end.

Unlawful Cause Art. 11. Meaning of words The words of a law must be given their generally prevailing meaning. Words of art and technical terms must be given their technical meaning when the law involves a technical matter.

Art. 12. Ambiguous words

When the words of a law are ambiguous, their meaning must be sought by examining the context in which they occur and the text of the law as a whole. A contract is absolutely null when it violates a rule of public order, as when the object of a contract is illicit or immoral. A contract that is absolutely null may not be confirmed. Absolute nullity may be invoked by any person or may be declared by the court on its own initiative.

Art. 2030. Absolute nullity of contracts

Art. 2033. Effects

An absolutely null contract, or a relatively null contract that has been declared null by the court, is deemed never to have existed. The parties must be restored to the situation that existed before the contract was made. If it is impossible or impracticable to make restoration in kind, it may be made through an award of damages. Nevertheless, a performance rendered under a contract that is absolutely null because its object or its cause is illicit or immoral may not be recovered by a party who knew or should have known of the defect that makes the contract null. The performance may be recovered, however, when that party invokes the nullity to withdraw from the contract before its purpose is achieved and also in exceptional situations when, in the discretion of the court, that recovery would further the interest of justice. Absolute nullity may be raised as a defense even by a party who, at the time the contract was made, knew or should have known of the defect that makes the contract null.

Art. 2983. Actions for payment of gaming The law grants no action for the payment of what has been won at gaming or by a bet,

debts and bets.

except for games tending to promote skill in the use of arms, such as the exercise of the gun and foot, horse and chariot racing.

Art. 2984. Actions for recovery of In all cases in which the law refuses an action to the winner, it also refuses to payments made on gaming debts and bets. suffer the loser to reclaim what he has voluntarily paid, unless there has been, on the part of the winner, fraud, deceit, or swindling. Unlawful Cause An obligation must not only have a cause, but that cause must be lawful, that is, neither illegal nor immoral, not contrary to public policy. (a) illegal forbidden by law (b) immoral runs counter to the moral standard of the community (c) against public policy contrary to values recognized as paramount by the community Lamy v. Will o When a party knowingly loans another money to pay a gambling debt, the borrower reneges on his promise to repay, then no civil action may be filed for recovery because, the law grants no action for the payment of what has been won at gaming or by bet except for games tending to promote skill in the use of arms, such as the exercise of the gun and foot, horse, and chariot racing, and an obligation without cause or with a false or unlawful cause can have no effect. Lauer v. Catalnotto TeleRecovery of Louisiana, Inc. v. Major o When a party is lended a sum of casino chips by two casinos and by his own volition gambles himself into debt, and is thereby unable to reimburse the lender, then in such a case the casino is warranted in collecting the funds from the lendee, because while, the law grants no action for the payment of what has been won at gaming or by a bet, the party did not have to gamble with the chips. McMahon v. Hardin Graviers Curator v. Carrabys Executor Cahn v. Baccich & De Montluzin o When parties are bidding for a piece of property, and one party actually wins the auction but the parties agree to flip a coin to see which party will actually acquire the property, if the party theyve agreed to allow to have the land defaults, then the party whose name is actually on the deed of sale is still bound to pay the seller because the plaintiffs had no part in the

agreement between the parties and the consideration was the $2500 of stock the plaintiff promised to deliver

Detrimental Reliance Art. 1967. reliance Cause defined; detrimental Cause is the reason why a party obligates himself. A party may be obligated by a promise when he knew or should have known that the promise would induce the other party to rely on it to his detriment and the other party was reasonable in so relying. Recovery may be limited to the expenses incurred or the damages suffered as a result of the promisee's reliance on the promise. Reliance on a gratuitous promise made without required formalities is not reasonable. Damages are measured by the loss sustained by the obligee and the profit of which he has been deprived

Art. 1995. Measure of damages

Detrimental Reliance If the promise was a gratuitous one made without required formalities, then the promisees reliance is deemed not reasonable. Recovery under this doctrine is discretionary with the court. The court can limit recovery to either the expenses incurred or the damages suffered by the promise. In Louisiana, there are three (3) elements of detrimental reliance: o a representation by conduct or word o justifiable reliance o a change in ones position to ones detriment Unreasonable Reliance o Reliance is unreasonable when placed on the kind of gratuitous promise for the validity of which a formality is required and the promise has been made only informally o Reliance on a gratuitous donation not made in authentic form is not reasonable Herbert v. Mcguire o When a doctor agrees to inform a patients insurance company of her claim, and fails to do so until after her account is past due and she is no longer able to file such a claim, then the doctor is only entitled to recover the percentage that the insurance company would not have paid, because

the plaintiff reasonable relied upon the doctors assertion and estoppel is not applicable. Edinburgh v. Edinburgh o When parties make an agreement that a couple will make repairs on a home and pay the mortgage until the owners death with the owners promise to leave the home to them in her will, and the couple divorces upon death of the owner, and the owner only lists one parties name in the will, then both parties are still entitled to their portion of the home because the other party relied upon that promise while performing repairs on the home. Kethley v. Draughon Business College, Inc. o When a party agrees to teach an extra class at a college and assumes that he will be compensated for such and is not, then the party is entitled to additional compensation, because it is reasonable to believe that an additional duty would accompany additional compensation. Martin v. Schluntz o When a tenant and a landlord are contracted by a month to month lease, and the tenant gives notice that he would like to take advantage of a lowered rental rate and in essence extend his lease, but the reduction of this agreement was never reduced to written form, and the landlord incurs 3 months of charges for lack of a tenant and necessary repairs, then the landlord may not recover any damages for such as no real agreement existed. Correct this- the guy promised to stay long term, changed nubdm det rel is enf because the lessor lent the property for a lesser price with the thinking that he would stay Barnett v. Bd. Of Trustees for State Colleges and Universities o When a party is promised that he will be made athletic director but no such agreement was properly submitted, then any damages suffered by him for reliance upon such a promise was unreasonable because the party knew that that Board approval was necessary to appoint him athletic director.

Applying the Theory of Cause Natural Obligations Art. 1760. Moral duties A natural obligation arises from circumstances in which the that may give rise to a law implies a particular moral duty to render a performance. natural obligation Art. 1761. Effects of a A natural obligation is not enforceable by judicial action. Nevertheless, whatever has been freely performed in natural obligation compliance with a natural obligation may not be reclaimed. A contract made for the performance of a natural obligation

is onerous. Art. 1762. Examples of Examples of circumstances giving rise to a natural circumstances giving rise to obligation are: a natural obligation (1) When a civil obligation has been extinguished by prescription or discharged in bankruptcy. (2) When an obligation has been incurred by a person who, although endowed with discernment, lacks legal capacity. (3) When the universal successors are not bound by a civil obligation to execute the donations and other dispositions made by a deceased person that are null for want of form. Art. 1888. Express or tacit A remission of debt by an obligee extinguishes the remission obligation. That remission may be express or tacit. Art. 1889. Presumption of An obligee's voluntary surrender to the obligor of the instrument evidencing the obligation gives rise to a remission presumption that the obligee intended to remit the debt. Art. 1890. Remission A remission of debt is effective when the obligor receives effective when the communication from the obligee. Acceptance of a communication is received remission is always presumed unless the obligor rejects the by the obligor remission within a reasonable time.

Natural Obligations 1) No form is required for natural obligations 2) A natural obligation operates as a cause of an obligation. 3) When a person feels a moral duty that is so strong toward another person, that duty becomes an element of a clearly identifiable relation called a natural obligation. 4) A natural obligation is not enforceable by judicial action. Nevertheless, whatever has been freely performed in compliance with a natural obligation may not be reclaimed. A contract made for the performance of a natural obligation is onerous.

Turning a Moral Duty into a Natural Obligation

1) the moral duty must be felts towards a particular person and not towards all person in general 2) special circumstances must exist that allow the inference that the person immersed in them feels so strongly about his moral duty that his conscience would not be placated unless that duty fulfilled, or in other words, that the person involved truly feels that he owes a debt. 3) the duty must be such that it can be fulfilled through rendering a performance whose object is of pecuniary value 4) a recognition of the obligation by the person who regards himself as obligor which may be made either by performing the obligation or by promising to perform it must occura recognition that brings the natural obligation into existence and simultaneously makes it into a civil one 5) fulfillment of the moral duty must not impair the public order Thomas v. Bryant o When a stepfather makes a promise and drafts a promissory note to pay of his stepsons rehab costs, then the promise is a moral duty that rises to the level of a natural oligation because, The moral duty felt was towards a particular person, not all persons in general; The person involved felt so strongly about the moral duty that he truly felt he owed a debt; The duty can be fulfilled through rendering a performance whose object is of pecuniary value; A recognition of the obligation by the obligor must occur, either by performing the obligation or by promising to perform; and the fulfillment of the moral duty must not impair the public order. Wortmann v. French o When a former husband transfers the deed to a house to his former wife by private act and for the purported consideration of $10, then the husband has created a natural obligation enforceable at law because a spouses desire to have a quick and clean divorce could be considered legitimate cause.

Performance not Recoverable A natural obligation is not enforceable by judicial action, but whatever has been freely performed in compliance with a natural obligation may not be reclaimed o Must be performed without duress, or under fraud, etc.

Promise to Perform- onerous contract According to Louisiana jurisprudence, to be enforceable, a debtors promise to perform his natural obligation must be clear, distinct and unequivocal, though no particular words need to be used. Where the cause is unlawful, the civil obligation will have no effect. When the necessary requirements are present, the contract that results from the debtors promise to perform his natural obligation is onerous. (the debtors intent is not to make a gift to the oblige but that he rather intends to pay a debt he feels he owes. He is not promising to give something w/o receiving anything in return, in which case the contract he makes would be a donation, and therefore gratuitous, but

he is promising something to compensate the oblige for something else from him received in the past, which suffices to make the contract onerous). Therefore, if the obligor intends to perform his natural obligation by making the kind of onerous contract for which a formality is exceptionally required, like the transfer of immovable property for example, the resulting onerous contract must be made in that form. Service Finance Co. of Baton Rouge Inc. v. Daigle o When a party declares bankruptcy prior to simply mentioning the existence of a debt, then such does not revive a debt, because, In order to revive a liability on a debt discharged in bankruptcy or to create a new enforceable obligation, there must be an express promise to pay the specific debt, made to the creditor or his agent, and while no particular form of language is necessary, to constitute such a new promise there must be a clear, distinct, and unequivocal recognition and renewal of the debt as a binding obligation, anything short thereof being insufficient, as, for example, the mere acknowledgment of the discharged debt, or the expression of hope, desire, expectation, or intention to pay or revive the same. Stoll v. Goodnight Corporation o When a bank employee accepts a hot check for $778.75 and in response to her employers comment that it would be to her advantage to repay the money, she does so and is later terminated, then she is not entitled to receive the reimbursement back in return, because, A natural obligation cannot be enforced by judicial action, but once a debtor recognizes and freely performs in response to a natural obligation, she cannot recover or reclaim what she has done or paid.

Remission of Debt The voluntary abandonment or renunciation of his right by the creditor in favor of his debtor Remission may be either: o Express may be made orally or in writing o Tacit when the creditor speaks no words, as when he destroys the instrument that evidences the obligation in the presence of the debtor; when it is the natural result of other words of the creditor, as when he gives the debtor a receipt for the full amount owed w/o having received payment; when he returns to the debtor the instrument that evidences the obligation after writing on the back thereof that the debt was canceled for services rendered that the creditor acknowledged as the equivalent of cash. Presumption of Remission Release of Real Security Contractual in nature, presumption of acceptance Gratituous or Onerous Inter vivos, No formality Required

Mortis Causa, Testament Required Hicks v. Hicks o When a mother sells a plantation to her son by authentic act for $10,000, payable in 20 annual payments of $500, and the son made the first 3 payments, and then the mother returned the other notes marked, cancelled for services rendered to me, which I acknowledge as the equivalent of cash, then the debt was remitted when she returned the notes because the remission of appellants debt on notes was complete and irrevocable when his mother surrendered the notes to him. Hurley v. Hurley o When a father agrees to turn over a certain piece of land to his son with the exception that the son take care of him in his old age, and the son complies for a period of time but later curses at the father, and threatens his life, and other acts of ingratitude, then the father may revoke the promise to transfer the land, because, "Donations inter vivos are liable to be revoked or dissolved on account of: (1) The ingratitude of the donee. (2) The nonfulfillment of the eventual conditions, which suspend their consummation. (3) The nonperformance of the conditions imposed on the donee," and the sons actions could be considered such ingratitude

Compromise Art. 3071. definition Compromise; A compromise is a contract whereby the parties, through concessions made by one or more of them, settle a dispute or an uncertainty concerning an obligation or other legal relationship.

Art. 3072. Formal A compromise shall be made in writing or recited in open court, in which case the recitation shall be susceptible of being transcribed requirements; effects from the record of the proceedings. Art. 3073. form Capacity and When a compromise effects a transfer or renunciation of rights, the parties shall have the capacity, and the contract shall meet the requirement of form, prescribed for the transfer or renunciation. The civil consequences of an unlawful act giving rise to a criminal action may be the object of a compromise, but the criminal action itself shall not be extinguished by the compromise. A compromise may relate to the patrimonial effects of a person's civil status, but that civil status cannot be changed by the compromise. Art. 3075. Relative effect A compromise entered into by one of multiple persons with an interest in the same matter does not bind the others, nor can it be raised by them as a defense, unless the matter compromised is a solidary obligation.

Art. 3074. Lawful object

Art. 3076. Scope of the act

A compromise settles only those differences that the parties clearly intended to settle, including the necessary consequences of what they express.

Art. 3078. After-acquired A compromise does not affect rights subsequently acquired by a rights party, unless those rights are expressly included in the agreement. Art. 3079. Tender and A compromise is also made when the claimant of a disputed or acceptance of less than the unliquidated claim, regardless of the extent of his claim, accepts a payment that the other party tenders with the clearly expressed amount of the claim written condition that acceptance of the payment will extinguish the obligation. Art. 3080. Preclusive effect A compromise precludes the parties from bringing a subsequent of compromise action based upon the matter that was compromised. Art. 3081. novation Effect on A compromise does not effect a novation of the antecedent obligation. When a party fails to perform a compromise, the other party may act either to enforce the compromise or to dissolve it and enforce his original claim. A compromise may be rescinded for error, fraud, and other grounds for the annulment of contracts. Nevertheless, a compromise cannot be rescinded on grounds of error of law or lesion.

Art. 3082. Rescission

Art. 3083. Compromise A compromise entered into prior to filing suit suspends the running of prescription of the claims settled in the compromise. If the suspends prescription compromise is rescinded or dissolved, prescription on the settled claims begins to run again from the time of rescission or dissolution.

Transaction or Compromise o An agreement whereby the parties put an end to litigation or prevent litigation form taking place(needs to be in writing). o Requirements: Existence of litigation The intention of putting an end to it Reciprocal concessions of the parties A dispute as to the amount due Nature of a Compromise o Onerous, synallagmatic, and consensual contract o Onerous

As the sacrifice each the parties makes of his rights or expectations is made in view of a reciprocal concession fo the other o Synallagmatic As both parties are obligated under the contract, each of them in view of the obligation contracted by the other o Consensual As consequence of which the formality of a writing is not required as a solemnity but for evidentiary purpose alone Cause in Transaction or Compromise o An end that each of the parties pursue individually and o Another end that both of them pursue in common o Elements: A claim liquidated or unliquidated An intention to put it to an end And reciprocal concessions of the parties Accord and Satisfaction o 1) an unliquidated or disputed claim o 2) a tender by the debtor o 3) an acceptance of the tender by the creditor Robert v. Carroll o When a party is involved in a car accident, and is examined by insurance company physicians prior to settling her claim, and after settling discovers that she is more severely injured that originally suspected, then she may not rescind the settlement upon such a finding, because, The subsequent discovery by a claimant that an injury was more serious than initially believed does not entitle the claimant to rescind the settlement and release agreement. Jamison v. Ludlow o When a party enters into a compromise to pay half of an existing debt and then the debtees feel that said compromise was made under fraudulent pretenses, then the compromise is invalid because, Fraud vitiates all contracts, and a contract induced by fraud, is, in fact, no contract, if the injured party chooses to repudiate it, because it wants the essential element of consent. Meyers v. Acme Homestead Assn RTL Corporation v. Manufacturers Enterprises, Inc. o When a party contracts to rent construction equipment, and there is a dispute as to the amount owed for such rentals, and the debtor renders a check for less than the amount the debtee feels is owing, then once the parties enter dispute as to the amount that is still owed and the debtee remains silent any compromise between the parties is considered to have been withdrawn because under circumstances as this silence can reasonably act as assent to the terms of an agreement.

Vices of Consent Art. 1942. Acceptance by When, because of special circumstances, the offeree's

silence

silence leads the offeror reasonably to believe that a contract has been formed, the offer is deemed accepted.

Art. 1943. Acceptance not An acceptance not in accordance with the terms of the in accordance with offer offer is deemed to be a counteroffer. Art. 1944. Offer of reward An offer of a reward made to the public is binding upon the offeror even if the one who performs the requested made to the public act does not know of the offer. Art. 1945. Revocation of An offer of reward made to the public may be revoked an offer of reward made to before completion of the requested act, provided the revocation is made by the same or an equally effective the public means as the offer. Art. 1946. Performance by Unless otherwise stipulated in the offer made to the public, or otherwise implied from the nature of the act, several persons when several persons have performed the requested act, the reward belongs to the first one giving notice of his completion of performance to the offeror. Art. 1947. Form When, in the absence of a legal requirement, the parties have contemplated a certain form, it is presumed that contemplated by parties they do not intend to be bound until the contract is executed in that form. Art. 1948. Vitiated consent Art. 1949. consent Consent may be vitiated by error, fraud, or duress.

Error vitiates Error vitiates consent only when it concerns a cause without which the obligation would not have been incurred and that cause was known or should have been known to the other party. that Error may concern a cause when it bears on the nature of the contract, or the thing that is the contractual object or a substantial quality of that thing, or the person or the qualities of the other party, or the law, or any other circumstance that the parties regarded, or should in good faith have regarded, as a cause of the obligation.

Art. 1950. Error concerns cause

Art. 1951. Other party A party may not avail himself of his error if the other party is willing to perform the contract as intended by willing to perform the party in error.

Art. 1953. Fraud may result Fraud is a misrepresentation or a suppression of the truth from misrepresentation or made with the intention either to obtain an unjust advantage for one party or to cause a loss or inconvenience to the other. from silence Fraud may also result from silence or inaction. Art. 1954. Confidence Fraud does not vitiate consent when the party against whom the fraud was directed could have ascertained the truth between the parties without difficulty, inconvenience, or special skill. This exception does not apply when a relation of confidence has reasonably induced a party to rely on the other's assertions or representations. Art. 1955. Error induced by Error induced by fraud need not concern the cause of the obligation to vitiate consent, but it must concern a fraud circumstance that has substantially influenced that consent. Art. 1956. Fraud Fraud committed by a third person vitiates the consent of a committed by a third person contracting party if the other party knew or should have known of the fraud. Art. 1957. Proof Art. 1958. Damages Art. 1959. Nature Fraud need only be proved by a preponderance of the evidence and may be established by circumstantial evidence. The party against whom rescission is granted because of fraud is liable for damages and attorney fees. Consent is vitiated when it has been obtained by duress of such a nature as to cause a reasonable fear of unjust and considerable injury to a party's person, property, or reputation. Age, health, disposition, and other personal circumstances of a party must be taken into account in determining reasonableness of the fear. (can arise from distressing circumstances( Error (Subjective) o Types of Error Bilateral error consent is vitiated if both parties are in error; in the alternative, the parties may reform the instrument to reflect their true mutual intent Unilateral error where only one party is in error, error will vitiate that partys consent if:

o it concerns a cause w/o which the obligation would not have been incurred, i.e., the error concerns the principle cause; and o this cause was known or should have been known to the other party Problems with Unilateral Error o Error concerns a cause when it bears on: (i) the nature of the contract (ii) the contractual object or a substantial quality of that object (iii) the person or the qualities of the other party (iv) anything the parties regarded or should have regarded in good faith as a cause; or (v) the law when a party has drawn erroneous conclusions of law and entered into a binding contract based on them The Principal Cause Requirement o ensures parties do not invoke error to get out of contracts on insignificant grounds. Thus, a party can rescind on the basis of error only if that party would not have bound himself if he had not suffered from this error. If the party would have entered into the contract despite the error, there is no vice of consent. The Knowledge Requirement o an attempt to treat the other party fairly. If the other party neither knew nor should have known that the party in error was binding himself because of this erroneous belief, then there is no vice of consent. Note that the requirement is that the other party knew or should have known of the cause. There is no requirement that the other party knew of the error, or that the other party held the same erroneous belief. Bordelon v. Kopicki o When parties enter negotiations to purchase to a house and mention to the sellers that their main objective in purchasing the house is finding one of suitable size that they can turn into a 4 bedroom home, without prior mentioning that the project would need to extend further onto the sidewalk, then the parties may not later claim that there was an error regarding their contracting to purchase the home, because, In order to invalidate a contract due to error, the error must relate to the principal cause for making the contract and the other party must either know or be presumed to know of this principal cause under La. Civ. Code Ann. art. 1949, and their prinicipal cause for purchase conflicting with the

Fraud Griffing v. Atkins o When a party invites another to have a ring appraised, and he and the other expert jewelers lead the owner to believe the ring was only worth $100 when it was actually valued at $1200, and allow the ring to be sold, then such constitutes fraud and misrepresentation, and the owner of the ring can rescind the sale if desired because, By disclosing only a part of which

you may say to be the truth and suppressing the remainder, that is fraud and vitiates a contract. Orr v. Walker o When a party conveys to another party that they are purchasing a tract of land for themselves, and the other party 76 years old and easily taken, reasonably relies on such conveyance, and the property was actually bought in favor of another, then the plaintiff is at liberty to discharge the sale because she constitutes fraud as the acts were misrepresentations presented as truth that caused inconvenience to the plaintiff. Overby v. Beach o When a party is in negotiations fro the sale of a set of apartments and the sellers convey a certain price acceptable to set the rent of the apartments at and, the purchaser fails to verify the accuracy of this information when doing so would be of no major inconvenience, then the purchaser may not claim that the purchase was made under fraud, because, No difficult or inconvenient operation was required of this plaintiff to discover the truth or falsity of the assertions charged to the Babins respecting the revenue production of the apartments, and she thereby could have avoided the sale she considered to be under misrepresentation.

Duress Couder v. Oteri o When a party is signs 3 mortgage notes, after being threatened to be killed, and the threats were made my someone through his counsel of legal proceedings which he had a right to use, then such does not amount to duress that would vitiate the contract, because Art. 1856 of the Civil Code, which provides that violence, used as a legal constraint, or threats of what the party had the legal right to do, cannot invalidate a contract. Wilson v. Aetna Cas. & Sur. CO. o When a 66 year old, illiterate man is involved in a serious automobile accident, and is hospitalized for 140 days, and his doctor suggests that he take a settlement due to his escalating medical bills, then he may not later rescind the acceptance of the settlement because, a contract entered into under duress that would cause fear of great injury to person, reputation, or fortune is invalid, even if the person favored by the contract did not exercise the violence or make the threats and was unaware of the duress. Adams v. Adams o When a party is entering divorce proceedings and chooses not to get her own attorney but to rely upon the legal counsel of her soon to be exhusbands brother who was her husbands representing attorney, and the husband threatens to file bankruptcy if she does not accept the settlement they agreed upon, and shakes her physically but never hits her, then such does not amount to duress that would vitiate a contract because, a threat if doing a lawful act or a threat of exercising a right does not constitute duress.

Object Art. 1971. Freedom of parties Parties are free to contract for any object that is lawful, possible, and determined or determinable. A contractual object is possible or impossible according to its own nature and not according to the parties' ability to perform. The object of a contract must determined at least as to its kind. be

Art. 1972. Possible or impossible object

Art. 1973. Object determined as to kind

The quantity of a contractual object may be undetermined, provided it is determinable. Art. 2450. Sale of future things A future thing may be the object of a contract of sale. In such a case the coming into existence of the thing is a condition that suspends the effects of the sale. A party who, through his fault, prevents the coming into existence of the thing is liable for damages. A hope may be the object of a contract of sale. Thus, a fisherman may sell a haul of his net before he throws it. In that case the buyer is entitled to whatever is caught in the net, according to the parties' expectations, and even if nothing is caught the sale is valid.

Art. 2451. Sale of a hope

Commerce Ins. Agency Inc. v. Hogue o When a party seeks to purchase a Book of Business from another party, and both parties know full well what this sale is to entail and that they were to receive CIAs accounts current list for the preceding 12 months, then the fact the description of such was not detailed in the contract does not cause the contract to be void due to absence of a specific object, because the quantity of a contractual object may be undetermined as long as it is determinable State v. Lewis o When an inmate charged with a felony is offered a plea bargain and he thinks that acceptance of the agreement will immune him from prosecution in other states, and the officer has no authority to make such a promise and the officer making the plea bargain is under the impression that the inmate will provide him with information regarding a crime that he in fact has no knowledge of the other crime, then the contract is void

for failure of cause because while a, plea bargain is a contract between the state an one accused of a crime, in this case both parties contracted for something other than what they could actually get. Henry R. Liles v. Bourgeois o When an the compensation agreed to be paid to an attorney is contigent upon the death of another party, then the conrtact is unenforceable because, Future things may be the object of an obligation. One cannot, however, renounce the succession of an estate not yet devolved, nor can any stipulation be made with regard to such a succession, even with the consent of him whose succession is in question.

Stipulation Pour Autrui or Third Party Beneficiary

Art. 1973. Object determined as to kind The object of a contract must be determined at least as to its kind. The quantity of a contractual object may be undetermined, provided it is determinable. Determination by third If the determination of the quantity of the object has been left to the discretion of a third person, the quantity of an object is determinable. If the parties fail to name a person, or if the person named is unable or unwilling to make the determination, the quantity may be determined by the court. Art. 1975. Output or requirements The quantity of a contractual object may be determined by the output of one party or the requirements of the other. In such a case, output or requirements must be measured in good faith. Art. 1976. Future things Future things may be the object of a contract.

Art. 1974. person

The succession of a living person may not be the object of a contract other than an antenuptial agreement. Such a succession may not be renounced. Art. 1977. Obligation or performance The object of a contract may be that a third person will incur an obligation or

by a third person

render a performance. The party who promised that obligation or performance is liable for damages if the third person does not bind himself or does not perform.

Art. 1978. Stipulation for a third party

A contracting party may stipulate a benefit for a third person called a third party beneficiary. Once the third party has manifested his intention to avail himself of the benefit, the parties may not dissolve the contract by mutual consent without the beneficiary's agreement. The stipulation may be revoked only by the stipulator and only before the third party has manifested his intention of availing himself of the benefit. If the promisor has an interest in performing, however, the stipulation may not be revoked without his consent. In case of revocation or refusal of the stipulation, the promisor shall render performance to the stipulator.

Art. 1979. Revocation

Art. 1980. Revocation or refusal

Art. 1981. Rights of beneficiary and The stipulation gives the third party stipulator beneficiary the right to demand performance from the promisor. Also the stipulator, for the benefit of the third party, may demand performance from the promisor. The promisor may raise against the beneficiary such defenses based on the contract as he may have raised against the stipulator.

Art. 1982. Defenses of the promisor