Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Building Corporate Brands

Transféré par

wana77Description originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Building Corporate Brands

Transféré par

wana77Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal of Marketing Communications Vol. 12, No.

4, 309320, December 2006

Case study

Building Corporate Brands through Community Involvement: Is it Exportable? The Case of the Ronald McDonald House in Norway

PEGGY SIMCIC BRNN

Norwegian School of Management, Oslo, Norway

ABSTRACT Community involvement is recognized as part of an organizations attempts to build good will in the local community and as such can be thought of as part of corporate social responsibility. The argument has been made that there is a need for more examination of the content of CSR activities, in particular for firms operating in diverse domestic and foreign contexts (Gardberg and Fombrun, 2004, Academy of Management Review, 31(2), pp. 329 346). This paper explores some of these issues by presenting an in-depth look at McDonalds community involvement initiative in Norway, where the attempts to build a Ronald McDonald House met much resistance and many barriers, many of them from political parties, doctors and academics. KEY WORDS: Community involvement, corporate social responsibility, cause related marketing, globalization, reputation

Introduction It can be argued that McDonalds record of corporate responsibility is one of the longest among US businesses. From the start of its franchise offerings in the 1950s, community involvement has been a requirement for participation. This is most evident through its Ronald McDonald Houses, a home away from home for families with critically ill children. McDonalds, through its community outreach charity, has actively used this concept of corporate social responsibility in at least 32 countries outside of the US resulting in the building of 217 Ronald McDonald Houses by

Correspondence Address: Peggy Simcic Brnn, Norwegian School of Management, Nydalsvn. 37, 0442 Oslo, Norway; Tel.: +47 46 41 06 70. Email: peggy.bronn@bi.no 1352-7266 Print/1466-4445 Online/06/04030912 # 2006 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/13527260600950643

310

P. S. Brnn

2003. The question that this article addresses is whether this concept, which is so successful in the US, can be exported into other countries. Multinationals in their attempt to think globally and act locally are advised to be more sensitive to local customs when it comes to adapting community involvement activities (Gardberg and Fombrun, 2004). We explore this by looking at the case of Norway, where the attempts to build a Ronald McDonald House met much resistance and many barriers, many of them from political parties, doctors and academics. First presented to the Norwegian government in 1998 and approved in 1999, the Norwegian Ronald McDonald House is scheduled for completion in 2007. Community Involvement Community involvement is all about a companys interaction with its immediate environment. Carroll and Buchholtz (2000) speak of community in terms of the immediate locale to a company the town, city or state in which a firm operates. Cannon (1994), alternativley, seems to equate the state with the community. Similar to Carroll and Buchholtz, he acknowledges that community has been broadened sometimes to include the region, the nation and even the world. Carroll and Buchholtz (2000) believe firms have a positive impact on the community in two ways: (1) donating the time and talents of its managers and employees; and (2) making financial contributions. In early work by Grunig and Hunt (1984), a firms community activities were defined as either expressive or instrumental. An expressive activity is one that a firm uses to promote themselves and to show goodwill. An instrumental activity is one that is designed to improve the community or make it easier to work there. Wheeler and Sillanpaa (1997) describe at least four categories of firms approaches to building community relations. One is the paternalism of the industrial era with magnates distributing wealth in the form of wages and direct investments. Extremely large firms become what the authors refer to as de facto component parts of the local arena. Another approach is community investment where headquarters of large firms distribute funds to community, cultural or sporting groups. A consultation approach is used by highrisk operations that use formal communication channels and information to influence community opinion. Lastly is the mutual development approach, where firms see the benefit to both their employees and the community of community volunteerism. A community is often the headquarters of the firm, and it provides the labor force, suppliers of other resources, utilities, and infrastructure and regulates the activities of the organization. Community involvement can be beneficial to both the firm and the community. Carroll and Buchholtz (2000) list a number of benefits to firms, including indirect benefits such as a healthier community and improved public image; employee benefits such as improved morale and attracting better employees; and bottom-line benefits such as increased employee productivity and the facilitation of achievement of goals. There are also numerous examples of the negative impact that firms have on communities. These may include pollution, heavily trafficked roads, noise, trash, and layoffs in bad times. The case of Wal-Mart in the US illustrates the backlash to some types of businesses. The website Wal-Mart Watch (walmartwatch.com/) accuses the

Building Corporate Brands through Community Involvement

311

store of having an impact on local poverty rates and of seizing private property in order to build their super stores. Wal-Mart Watch has teamed up with Sprawl Busters to go to battle to stop Wal-Mart from taking over communities. Americas Union Movement accuses big box stores such as Wal-Mart of destroying local communities sense of pride and place because of their unimaginative architecture and huge paved parking lots. Finally, Reclaim Democracy.org (http:// reclaimdemocracy.org/walmart/) assists communities in resisting the power of WalMart. They offer a complete source of information on the firm and its community practices. Evidence of the recognition of community involvement for reputation building is its appearance in corporate reputation rankings instruments such as the Reputation Quotient, which includes community responsibility as part of its overall social responsibility measurement. Fortunes Most Admired Firms in the US survey also ranks firms on Responsibility to the Environment and Community. Some large organizations also have special communication departments to deal specifically with community relations. Argenti and Forman (2002) cite a Conference Board report on senior communications executives activities in hundreds of Americas largest firms. More than 60% list community relations as part of their responsibilities. A study by Business in the Community/Research International (UK) Ltd found that nearly three-fourths of marketing and community affairs directors devote at least part of their budgets to cause related marketing, i.e. forming alliances with typically nonprofit agencies to market an image, product or service for mutual benefit (Adkins, 2000, p. xviii). This includes community involvement activities. There are many books and articles outlining good practices and benchmarking when it comes to carrying out community involvement activities, many written in the public relations field (cf Wilcox and Cameron, 2006, Lattimore et al., 2004). Adkins (2000) provides a comprehensive selection of different types of surveys of what she refers to as cause related marketing, which includes community involvement activities. However, there appears to be little empirical research specifically addressing different dimensions of community involvement. Keller and Aaker (1998) performed one of the few studies attempting to correlate corporate marketing of community involvement activities to consumer perceptions of (1) corporate likeability and trustworthiness; (2) quality of brand extension; and (3) purchase likelihood for the brand extension. The researchers argued that community involvement should have similar effects as perceived environmental concerns, an area that has received more attention (cf. Mohr et al., 1998). While Keller and Aaker found acceptance for their first hypothesis, community involvements positive correlation with likeability and trustworthiness, they found that firms corporate marketing of their community involvement had a lesser effect than marketing activities that demonstrated product innovation and environmental concern. However, the authors note that while community involvement has little impact when it comes to brand extensions, it may have more impact on consumers when it comes to existing brands and products. In another study of the relationship between the success of small businesses and their level of social responsibility, Besser (1999) focused on commitment to and support for the community. His results show that older businesses and those with more employees are significantly more likely to be committed to and provide support

312

P. S. Brnn

and leadership to the community (p. 25). He additionally found strong support that community support is good for business, at least in small town settings. Adapting Community Involvement Globally Community involvement is an international activity, i.e. it is not peculiar to any one country or part of the world (cf. Carroll and Buchholtz, 2000; Adkins, 2000; Cannon, 1998). As McIntosh et al. (1998) note, companies once based their headquarters in a single city or town and concentrated their community involvement exclusively in that headquarters location. Many firms today have multiple bases or headquarters, and even if they are not physically located in a country, their products may be there. This begs the question of whether community involvement activities accepted in one country or culture are accepted in others. This is of particular interest for large multinationals practicing corporate social responsibility in the form of community involvement activities. They need to consider if they should (1) do the same things in all the countries in which they operate or sell products; or (2) consider accommodating local norms and practices. Gardberg and Fombrun (2006) suggest that firms operate in diverse foreign contexts and that the model of corporate citizenship they employ should acknowledge this. They further state that appropriateness of the activities to the local conditions determines the effectiveness of the CSR initiative. The researchers define appropriateness as the degree to which the companys citizenship profile falls within the range of acceptability defined by local institutional conditions (p. 336). According to Gardberg and Fombrun (2006), two factors influence expectations by local stakeholders of what constitutes acceptable citizenship activities national and industry factors. The philosophical, cultural and economic features of national systems will greatly influence what local groups believe is the role of global companies in the local community (Gardberg and Fombrun, 2006). The authors cite examples of national differences such as legally mandated laws on minimum age of employment, the level of corruption and economic development in different countries, and values, beliefs, norms and assumptions held about human nature and behavior. The authors conceptualize a firms range of acceptability based on their home countrys level of expectation and the level of citizenship activities they are expected to carry out in a host country (see Figure 1). Four situations are illustrated ranging from Quadrant I with low expectations for both home and host markets to Quadrant 4 with high expectations from both the home and host country. Here the firm is viewed as an expansionist, doing even more than what is expected in their home country. The authors use as an example Japanese firms adapting their citizenship activities to the North American market in order to gain legitimacy. The point is that failure to recognize the differences between home and host country environments can result in citizenship efforts not being accepted by the host country. This in turns leads to an inability to build reputation value from the efforts. Hill (2004) also suggests a number of other issues that arise from a global CSR strategy. These include whether or not the concept adds to a firms reputation in a way that leads to local advantage, the characteristics of countries where the concept is most effective, the firms attitudes toward the countries in question, and whether

Building Corporate Brands through Community Involvement

313

Figure 1. Citizenship expectations, the range of acceptability and customization (Gardberg and Fombrun, 2006)

the strategy has helped the firm facilitate globalization. Obviously, as noted by Gardberg and Fombrun (2006), there is a need for further examination of the content of CSR activities, in particular for firms operating in diverse domestic and foreign contexts. This paper explores some of the issues above by presenting an in-depth look at the case of McDonalds in Norway, where the attempts to build a Ronald McDonald House met much resistance and many barriers, many of them, as stated previously, from political parties, doctors and academics. The case is introduced with information on McDonalds corporate social responsibility efforts through community involvement and the Ronald McDonald House. This is followed by a review of the history of McDonalds in Norway and the story of the long struggle of McDonalds to establish the concept in Oslo, Norway. McDonalds and the Ronald McDonald House It can be argued that McDonalds record of corporate responsibility is one of the longest among US businesses. From the start of its franchise offerings in the 1950s, community involvement has been a requirement for ownership. As noted by McDonalds founder Ray Kroc, We have an obligation to give back to the communities that give us so much (www.mcdonalds.com). Owners and operators must have intimate knowledge of the communities where they operate. This sense of community means that restaurants optimally should be locally owned and operated, use local suppliers and employ local residents. Tom Feltenstein, founder of the Neighborhood Marketing Institute, credits Ray Croc for giving him the religion of

314

P. S. Brnn

neighborhood marketing (2003), a concept where each restaurant is part of the local business community. One lesson he learned while working for the McDonalds corporation and Kroc was the importance of community involvement. Advertising agencies were required to have field executives who, according to Feltenstein, worked on the ground, meaning they did the dirty work of birthday parties, grand openings, etc. A symbol of this community involvement is the organizations Ronald McDonald House. Started in 1974 in cooperation with the American football team the Philadelphia Eagles, the concept is designed to give families with critically ill children a place to stay in a home environment while their children undergo treatment at a local hospital. Today, the effort is coordinated through the Ronald McDonald House Charities, which has awarded more than USD 320 million in grants worldwide. More than 200 Ronald McDonald Houses have been established in 32 countries around the world. McDonalds and the Ronald McDonald House in Norway McDonalds opened its first restaurant in Norway in the capital city Oslo on 18 November 1983. Not only did the Mayor of Oslo attend the party the day before the grand opening, but also the US ambassador to Norway was there. The crowds were so great in the first few days that the restaurant often had to turn people away. The firm has continued its popularity, experiencing growth nearly every year since its beginnings, in 2003 enjoying a turnover of over 1 billion NOK, or about USD 145 million, a 6% increase from the year before. Today, this turnover is spread over 64 restaurants throughout the country, most owned as franchises through McDonalds Norway AS, which is 50% owned by a single individual, Theo Holm. The history of McDonalds in Norway has not always been so rosy. They were affected by the criticism of Sting in 1989, that they contributed to the destruction of the rain forest (later recanted by the singer). In 1989, guests and employees were barricaded in the Oslo restaurant for several hours while youth from a local activist group demonstrated against the company. They have experienced at least one food poisoning case (never proven) and were criticized for a McAfrica campaign as being insensitive to the plight of the third world. The restaurants are regularly cited in a negative context as representing undesirable values and unhealthy food. These types of comments regularly surface in the media in Norway, but it hit new heights when the Norwegian Ministry of Social and Health Services in 1999 said yes to the Norwegian Ronald McDonald Childrens Funds request to build a Ronald McDonald House in cooperation with the then National Hospital (it is now a regional university hospital). Approval was needed from the Norwegian government, as the health system in Norway is a public good administered by the National Ministry for Health. While the management of the hospital was positive to the concept (in fact Sverre O. Lie, a professor from the hospital, initiated the effort), the minister of health had problems with a large commercial company being seen as a sponsor of a public institution. The consent from the Health Ministry was one of the rare times the government approved sponsorship of a public health organization by an actor from the private sector, representing a landmark in Norwegian history. The reason for approving the

Building Corporate Brands through Community Involvement

315

project was stated as follows by Idar Magne Holme from the Norwegian Health Ministry, The goal of the project is so positive that we have given the National Hospital permission to negotiate further with the Ronald McDonald Childrens Fund. He went on to emphasize that an extremely important factor was providing families with sick children a good living arrangement. With the condition that the government has full control of the project and that the Ronald McDonald Childrens Fund can not be involved in the running of the facilities, added Holme. The decision by the governments to allow this alliance and the fact that the company was McDonalds caused an outpouring of sentiment, mostly negative. The principal Norwegian arguments against the alliance were two-fold: one is that the private sector should stay out of the business of the public sector and two that McDonalds is the worst example of a firm with which a public hospital should have an alliance. An additional issue affecting the firm is advertising to children, something that is not allowed in Norway. The first argument is rooted in Norwegian social democracy where there are clear lines between what the social sector provides and where the private sector should be involved. No area has received so much attention as the health sector and today there are few private offerings in this sector, but they are growing. Storting representatives from the Center Left party were quick to attack McDonalds proposition for the Ronald McDonald House for this reason (NRK P2, 1999). They believe that by being public and avoiding too close ties to private actors (including pharmaceuticals) the health system maintains a higher integrity. The discussion (TV2, 2004) of developing a Norwegian version of the US Extreme Makeover TV show spotlighted this argument, as many plastic surgeons have left the public health sector in favor of private clinics. A young female Storting member argued on a TV talk show that the backlog of women waiting for reconstructive breast surgery in the public health system could be blamed on the drain of doctors to the more lucrative private sector. The private sector blames the backlog on the governments under funding of hospitals. The second argument has to do with the products offered by McDonalds and the fact that it is American. The restaurants products have been criticized for contributing to an overweight population, particularly youth. This is a relatively new phenomenon in Norway and is linked to their national identity. Part of this national identity is the enjoyment of nature and outdoor life and of how this enjoyment contributes to maintaining good health. A local saying goes something like, There is no such thing as bad weather, just bad clothing. McDonalds is associated with fast food, overweight children, and poor exercise habits, all part of the American identity, according to Norwegians. Media documentaries (TV Norge, 2004) on the matpakke phenomenon have added to this discussion. A staple part of the Norwegian diet is the typical homemade lunch eaten by many Norwegians at work. This usually consists of at least two open-faced sandwiches of multi-grained bread with some sort of spread, often goats cheese (brun ost). Professor Hylland Eriksen (1996), a Norwegian expert in multicultural identity, notes As in other countries, mass culture in Norway is nearly synonymous with American culture: pop and rock, jeans and t-shirts, American films, TV series such as Baywatch, burgers and cola. The perception in Norway is that this influence has lessened the national identity so closely associated with exercise and good health.

316

P. S. Brnn

Hylland Eriksen feels that the fact that American hamburger chains have become common in the country has added to the renewed interest in the countrys national identity. This has perhaps contributed to the spotlight on McDonalds. The third issue is advertising to children. Protecting young children from the pressures of commercial messages is a role of the Norwegian government and a special part of Norwegian identity. Special initiatives are continuously drafted to educate children on consumerism, to teach them how to recognize advertising versus other types of messages, or to strengthen current laws preventing commercial messages to children in a wide range of media (Odin, Press release No. 02023: 25.04.02). The governments primary argument banning advertising to children is that it can easily have a great effect on them. Many of the arguments are based on advertisings impact on childrens self-perception, which, for example, might lead to eating disorders in adolescents. Advertising is seen as directly appealing to children if:

N N N N

A product or service is of particular interest to children It is broadcast at a time where children are more likely to watch It directly influences children under 13 It uses animation or other presentation forms that particularly appeal to children. (Odin, 2001)

Part of the governments concerns also has to do with advertising in the offentlig rom, directly translated as public space, for example a hospital (Odin, 20052006). They argue that people should have some space where they are not bombarded with commercial messages. This has included sports competition and training camps where the countrys largest milk producer has been criticized for sponsoring childrens sports programs. The McDonalds Happy Meal obviously is a product with an appeal to children and the Ronald McDonalds character is directly linked to children. In both cases, the firm is prevented from advertising directly to children in the media, including their webpage. McDonalds 20022003 As noted, the Storting gave the green light for the Ronald McDonald House in 1999, but the project immediately ran into a number of hindrances in addition to the initial reactions described above. First, the hospital moved to a new location, which itself was delayed several times. There was then disagreement on the site of the house and the purchase of the piece of land where it was to be located. Finally, in 2002 the hospitals board approved the Ronald McDonald House project and authorized management to complete negotiations with the Ronald McDonald Childrens Fund. As in 1999, this started a flurry of reactions in the media. Horrible! was the response from nutrition professor and obesity expert Tore Henriksen in the media (Thoresen, 2002). This is horrible and is not appropriate for a public institution or for the countrys health policy. His position was that the alliance with McDonalds signals that hamburgers, cola and French-fried potatoes are good food. He concluded his remarks with the comment that unfortunately rich food companies could now promote themselves through such projects. In the same article, Roald Bahr, professor and assistant director of the governments council for nutrition and physical activity, said the problem with overweight children in Norway

Building Corporate Brands through Community Involvement

317

is a ticking bomb. He sees this development as a beginning of a pattern that is fully developed in the US, where he contends it is normal to be overweight. While not directly criticizing McDonalds, his implication is clear. A newspaper in Bergen on the west coast (Bergens Tidende, 2002) reported skepticism to firms that support non-profit organizations, specifically drawing in doubt McDonalds project with the hospital in Oslo. Trond Blindheim, a sociologist and marketing professor, sarcastically viewed the Ronald McDonald House as having great advertising value for the restaurant (NRK P2, 2002). I think it is incredible that doctors behave like idiots running the marketers errands. McDonalds is trying to improve their reputation and increase the attractiveness of their own firm with this project because their products will no longer be associated with something that makes us sick and unhealthy, but something that is associated with good health. Over time this is meant to create associations with something that is healthy and of greater social value, according to Blindheim. The Center Left politician Olav Gunnar Ballo agrees that McDonalds is not doing this out of idealism. This is pure marketing for a brand. He believes the money should come from public budgets through the government. It is the public sectors job to run hospitals in Norway and their responsibility to promote togetherness between children and parents. Hospitals should be an advertising-free zone. A letter to the editor lamented the inability to get away from American products in Norway and views the Ronald McDonald House as the last straw, forcing him to flee Oslo for the comfort of the forest and her traditional Norwegian chocolate bar (Loretzen, 2003): No country in Europe is more Americanized than Norway. My PC is from IBM with Microsoft programs. I have Post It Notes, marking pens and even colleagues with titles like marketing director and coach. And McDonalds, 20 years after they opened their first restaurant in Oslo, now sell burgers for more than NOK 900 million per year. And now the company has started building a Ronald McDonald House for children. There is nothing left to do but to leave the city with a red nisselue (wool cap) pulled down over my ears. On a tree stump in the forest I can sit down and pull out a Freia Melkesjokolade a little piece of Norway. But when I unfold the wrapper I spot five letters on the backside, KRAFT. (Authors note: The US firm Kraft Foods currently owns Norways most traditional chocolate manufacturer Freia.) The criticism was compounded during this time by a letter written by 50 Norwegian doctors and academics criticizing a McDonalds UNICEF project for World Childrens Day (Thoresen, 2002). The letter writers believe that UNICEF undermines its work with childrens health issues by associating with the fast food restaurant. McDonalds is a leader in the global marketing of junk food that creates sky high numbers of overweight children and type 2 diabetes and destroys traditional ways to make food in families and cultures. While the management of the hospital is very favorable to the project, and was a real champion for it through one of their senior researchers and doctors, they feel

318

P. S. Brnn

that they must tread carefully. As noted by a director of the hospital, Since this is the only way to get such a facility in these difficult hard times, and the project is well known in other countries, we are satisfied, but we would prefer a sponsor with a better fit. We also have similar issues with pharmaceutical companies, so we are working to develop good ethical policies that we can use for such situations (interview, 2003). Health authorities have similar feelings. They are skeptical to sponsorship of health services, but accept the agreement between the hospital and McDonalds. They will be watching how the restaurant profiles itself when it comes to the gift, meaning their cause related marketing tactics. There are a number of supporters for the Ronald McDonalds concept, primarily from non-profit organizations work with sick children. These include the Norwegian Cancer Society and their Support Organization for Children with Cancer and the Organization for Children with Heart Disease. McDonalds has also been successful in raising parts of the funds for building the house from customers, and one Norwegian motorcycle enthusiast is dedicating his two-year around the world tour on two wheels to raising money for the Ronald McDonald House. The Norway house was originally scheduled for completion in 2006. As of summer 2006, the date for starting construction was changed to December 2006, with completion November 2007. As noted by a McDonalds communication consultant, We are crossing our fingers that this will now be a reality. The Ronald McDonalds Childrens Fund in Norway still has a way to go to raise the approximately NOK 30 million it is expected to cost. As of May 2006, they had reached about 12 million with a number of fund raising initiatives planned for the coming year. Most of the funding, about 1 million Kroner per year, comes from regular customers who donate money through the collection boxes on the counters in the restaurants. Several initiatives are designed to help build public awareness, which will be key, as the awareness of the Ronald McDonald House concept in Norway has stayed steady at around 25%; about half of that in Sweden and Denmark (see Table 1). Initiatives include a McHappy Day/World Childrens Day and a Ronald McDonald Charity Golf Cup. Further, the firm has enlisted three well known Norwegians as Ronald McDonald House ambassadors, the pro golfer Suzann Pettersen, Olympic alpine gold medal winner Kjetil Andre Aamodt and actor Thoralv Maurstad. Another fund raising tactic will be sponsorship of 250,000 kroner from suppliers and partners of rooms and leaves for a tree of life. A challenge here of course will be finding firms that fit the profile desired by the hospital and who are willing to be

Table 1. Awareness of Ronald McDonald House in Norway, Sweden and Denmark (Fast Track data furnished by McDonalds Norway.) Q3 2004 23 63 38 Q4 2004 24 67 40 Q1 2005 28 43 42 Q2 2005 22 46 43 Q3 2005 25 49 46 Q4 2005 26 46 49

RMHC awareness Norway Sweden Denmark

Building Corporate Brands through Community Involvement

319

associated with McDonalds. This may be more difficult than all of the other tactics. Conclusion The director of communications of McDonalds Norway (an American) is quoted as believing that Norway is comparable to the United States (Eriksen, 2003). The journalist immediately attacked this statement by reminding her that these two countries are not obviously comparable. (She later stated that she had been misquoted.) However, her statement raises the point of this case it is not obvious that the Ronald McDonald House is going to be a success in Norway just because it is in the US, or even other European countries. Obviously, the families with ill children will be more than grateful to have access to the accommodations, and the hospital is able to offer something that is of significant value and necessity. Key is how McDonalds will measure success. If it is in the form of return to their image, they might be disappointed. Except for the health organizations working with children there is no evidence that the Ronald McDonald House is achieving very much positive attention from consumers in general. This may change of course as the restaurants public relations agency starts their campaigns, but they have a number of challenges: overcoming the American versus Norwegian identity issue and the fact that the Ronald McDonald House may be just too American for most Norwegians to swallow. Obviously, it will be interesting to follow the campaigns and to continue research on the project as it nears completion. The awareness numbers will clearly have to increase but they will have to be accompanied by equally high likeability scores. This case raises a number of interesting issues, but primarily it encourages reflection about conceptions of corporate social responsibility from a national point of view. The acceptance of initiatives in one country doesnt necessarily mean acceptance in all countries. Multinationals need to address these issues and not just assume their own national norms are the accepted ones. Put another way, a homogeneous internationalization policy may not be possible for companies practicing CSR, at least not through community involvement. Clearly, more research is necessary to explore these issues. This paper was only meant to illustrate the difficulties of one multinational firm in its efforts to do something good for a local community outside of its home country. It is interesting to note that some of Wal-Marts issues with local communities have followed them to Europe as trade unions sent them the message in 2003 Not in our country, not in our neighborhood (www.union-network.org). Arguably, the attacks on McDonalds both internationally and in Norway have some basis for legitimacy, and in 2003 it looked like perhaps this negative attention was going to finally cause significant damage to the firm as it experienced a substantial decrease in sales and the closing of a number of outlets around the world. However, the firm rallied back. Through upgrading their menu, hiring nutritionists, offering consumer education through their webpage, they are now acknowledged as making an effort answering the call for more responsibility in their offerings and behavior. Perhaps Norwegians will interpret this as an attempt to meet their national identity of good health and exercise.

320

P. S. Brnn

References

Adkins, S. (2000) Cause Related Marketing, Who Cares Wins (Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann). Argenti, P. A. & Forman, J. (2002) The Power of Corporate Communication (New York: McGraw Hill). Bergens Tidende (2002) 17 November. Besser, T. L. (1999) Community involvement and the perception of success among small business operators in small towns, Journal of Small Business Management, July, pp. 1929. Cannon, T. (1994) Corporate Responsibility (London: Pitman Publishing). Carroll, A. B. & Buchholtz, A. K. (2000) Business and Society, Ethics and Stakeholder Management (Cinn, OH: South-Western College Publishing). Dagbladet (2002) 9 October, available at: www.dagbladet.no/dinside/2002/09/10/348403.html. Eriksen, T. G. (2003) Sponset sykehus, Dagbladet, 25 November. Gardberg, N. A. & Fombrun, C. J. (2006) Corporate citizenship. creating intangible assets across institutional environments, Academy of Management Review, 31(2), pp. 329346. Grunig, J. E. & Hunt, T. (1984) Managing Public Relations (Orlando, FL: Holt, Rinehart and Winston). Hill, J. S. (2004) Globalization, Strategy and Analysis (South-Western College Publications). Hylland Eriksen, T. (1996) Globalisation and Norwegian identity, Nytt fra Norge, Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Keller, K. L. & Aaker, D. A. (1998) The impact of corporate marketing on a companys brand extensions, Corporate Reputation Review, 1(4), pp. 356378. Loretzen, T. (2003) 12 timer utenfor Bushen, Verdens Gang, 15 February. Lattimore, D. et al. (2004) Public Relations the Profession and the Practice (NY: McGraw Hill). Mohr, L. A. et al. (1998) The development and testing of a measure of skepticism toward environment claims in the marketers communications, Journal of Consumer Affairs, 32(1), pp. 3055. McIntosh, M. et al. (1998) Corporate Citizenship, Successful strategies for responsible companies (London: Pitman Publishing). NRK P2 (2003) Dagsnytt, Debattt om McDonalds sykehushotell. 25 November. Odin (2001) NOU 2001:6, Rettslige rammevilkar for markedsfring, 15 February. Odin (20052006) st.prp.nr.1. Available at: www.odin.no Thoresen, J. (2002) McDonalds pa Rikshospitalet, Dagbladet, 10 September. Wheeler, D. & Sillanpaa, M. (1997) The stakeholder corporation (London: Pitman Publishing). Wilcox, D. L. & Cameron, G. T. (2006) Public Relations Strategies and Tactics, (8th ed.) (Boston: Pearson Education).

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Dell Compellent Sc4020 Deploy GuideDocument184 pagesDell Compellent Sc4020 Deploy Guidetar_py100% (1)

- Financial Analysis of Wipro LTDDocument101 pagesFinancial Analysis of Wipro LTDashwinchaudhary89% (18)

- Form Active Structure TypesDocument5 pagesForm Active Structure TypesShivanshu singh100% (1)

- Mpu 2312Document15 pagesMpu 2312Sherly TanPas encore d'évaluation

- Rubric 5th GradeDocument2 pagesRubric 5th GradeAlbert SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Prlude No BWV in C MinorDocument3 pagesPrlude No BWV in C MinorFrédéric LemairePas encore d'évaluation

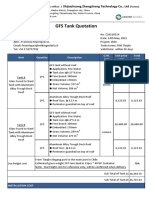

- GFS Tank Quotation C20210514Document4 pagesGFS Tank Quotation C20210514Francisco ManriquezPas encore d'évaluation

- Paradigms of ManagementDocument2 pagesParadigms of ManagementLaura TicoiuPas encore d'évaluation

- CFO TagsDocument95 pagesCFO Tagssatyagodfather0% (1)

- Learning Activity Sheet: 3 Quarter Week 1 Mathematics 2Document8 pagesLearning Activity Sheet: 3 Quarter Week 1 Mathematics 2Dom MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- Problem Set SolutionsDocument16 pagesProblem Set SolutionsKunal SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mutual Fund PDFDocument22 pagesMutual Fund PDFRajPas encore d'évaluation

- MQC Lab Manual 2021-2022-AutonomyDocument39 pagesMQC Lab Manual 2021-2022-AutonomyAniket YadavPas encore d'évaluation

- Key Fact Sheet (HBL FreedomAccount) - July 2019 PDFDocument1 pageKey Fact Sheet (HBL FreedomAccount) - July 2019 PDFBaD cHaUhDrYPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment - Final TestDocument3 pagesAssignment - Final TestbahilashPas encore d'évaluation

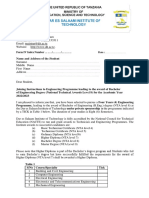

- Joining Instruction 4 Years 22 23Document11 pagesJoining Instruction 4 Years 22 23Salmini ShamtePas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 4 DeterminantsDocument3 pagesChapter 4 Determinantssraj68Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anti Jamming of CdmaDocument10 pagesAnti Jamming of CdmaVishnupriya_Ma_4804Pas encore d'évaluation

- Brochure en 2014 Web Canyon Bikes How ToDocument36 pagesBrochure en 2014 Web Canyon Bikes How ToRadivizija PortalPas encore d'évaluation

- Guia de Usuario GPS Spectra SP80 PDFDocument118 pagesGuia de Usuario GPS Spectra SP80 PDFAlbrichs BennettPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumers ' Usage and Adoption of E-Pharmacy in India: Mallika SrivastavaDocument16 pagesConsumers ' Usage and Adoption of E-Pharmacy in India: Mallika SrivastavaSundaravel ElangovanPas encore d'évaluation

- WWW - Commonsensemedia - OrgDocument3 pagesWWW - Commonsensemedia - Orgkbeik001Pas encore d'évaluation

- eHMI tool download and install guideDocument19 pageseHMI tool download and install guideNam Vũ0% (1)

- ArDocument26 pagesArSegunda ManoPas encore d'évaluation

- Excess AirDocument10 pagesExcess AirjkaunoPas encore d'évaluation

- Masteringphys 14Document20 pagesMasteringphys 14CarlosGomez0% (3)

- Chapter 19 - 20 Continuous Change - Transorganizational ChangeDocument12 pagesChapter 19 - 20 Continuous Change - Transorganizational ChangeGreen AvatarPas encore d'évaluation

- Crystallizers: Chapter 16 Cost Accounting and Capital Cost EstimationDocument1 pageCrystallizers: Chapter 16 Cost Accounting and Capital Cost EstimationDeiver Enrique SampayoPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Service Exam Clerical Operations QuestionsDocument5 pagesCivil Service Exam Clerical Operations QuestionsJeniGatelaGatillo100% (3)

- Training Customer CareDocument6 pagesTraining Customer Careyahya sabilPas encore d'évaluation