Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Organization As Design

Transféré par

chouvDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Organization As Design

Transféré par

chouvDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Making

Difference:

as Organization Design

A. GeorgesL. Romme

Box 90153, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Tilburg University, PRO. 5000 LE Tilburg, The Netherlands a. g. 1. romme@uvt.nl

Abstract

Mainstream researchis based on science and organizational the humanities. Science helps us to understand organizedsystems, from an outsider position, as empiricalobjects. The humanities contribute understanding, criticallyreflectto and the humanexperienceof actorsinside organized ing on, practices. Thispaperarguesthat,in view of the persistent relevance studies should gap betweentheoryand practice,organization be broadened includedesign as one of its primary to modesof engagingin research.Design is characterized its emphasis by on solutionfinding,guidedby broader purposesand ideal target systems.Moreover, design develops,and drawson, design propositionsthat are tested in pragmaticexperimentsand in science.This studyfirstexploresthe grounded organization main differencesand synergiesbetween science and design, and explores how and why the design disciplinehas largely movedawayfromacademia othersites in the economy.The to then turnsto the genealogyof designmethodologies argument in organizationand managementstudies. Subsequently, this that serves to paperexploresthe circulardesign methodology illustratethe natureof design research,that is, the pragmatic focus on actionable knowledgeas well as the key role of ideal targetsystemsin designprocesses.Finally,the author proposes a frameworkfor communication and collaboration between the science and design modes, and argues that scholars in studies can guide humanbeings in the process organization of designingand developingtheir organizations towardmore and futures.In this respect, humane,participative, productive the organization disciplinecan makea difference.

(Design; Pragmatism;OrganizationScience; Design Propositions;Design Rules; Epistemology)

Introduction

Organizational research is currently based on the sciences and humanities, which are its main role models. Science helps to understand organized systems by uncovering the laws and forces that determine their characteristics, functioning, and outcomes. Science itself is based on a representationalview of knowledge, in which organizational phenomena are approached as empirical objects with descriptive properties (Donaldson 1985, 1996; Mohr 1982). The descriptive and analytic nature of science helps to explain any existing or emerging organizational phenomena, but cannot account for qualitative novelty (Bunge 1979, Ziman 2000). In this respect, the notion of causality underpinning science is the study of variance among variables, the linkage of a known empirical phenomenon into a wider network of data and concepts; science tends to focus on testing propositions derived from general theories. Organizational research that draws on the humanities as its main role model assumes knowledge to be constructivist and narrative in nature (e.g., Denzin 1983, Gergen 1992, Parker 1995, Zald 1993). This implies that all knowledge arises from what actors think and say about the world (Gergen 1992). The nature of thinking and reasoning in the humanities is critical and reflexive (Boland 1989). Thus, research focuses on trying to understand, interpret, and portray the human experience and discourse in organized practices. In this way, the goal of appreciatingcomplexity is given precedence over the goal of achieving generality. Building on Herbert Simon's (1996) writings, this paper argues for a design approach to organization studies. The idea of design involves inquiry into systems that do not yet exist-either complete new systems or new states of existing systems. The main question thus becomes, "Will it work?" rather than, "Is it valid or true?" Design is based on pragmatism as the underlying epistemological notion. Moreover, design research draws on "design causality" to produce knowledge that is both actionable and open to validation. An important characteristic of design is the use of ideal target systems when defining the initial situation.

1047-7039/03/1405/0558

the Design... is the principalmarkthat distinguishes professions from the sciences. Schools of engineering,as well as schoolsof architecture, business,education, andmedicine, law, are all centrallyconcernedwith the processof design (Simon 1996, p. 111). Thereexists a designerlyway of thinkingand communicating thatis both differentfrom the scientificand scholarlyways of and thinkingand communicating, is as powerfulas the scientific andscholarlymethodsof enquiry, whenappliedto its own kinds of problems(Archer1984, p. 348).

ORGANIZATION SCIENCE ? 2003 INFORMS Vol. 14, No. 5, September-October 2003, pp. 558-573

526-5455electronicISSN

as A. GEORGESL. ROMME Organization Design

The main argumentin this paper is that the study needs a design mode, as much as sciof organization ence and humanitiesmodes, of engaging in research. In this respect, science and humanitiesuse and study the creations of human design. The notion of design may therefore contributeto solving the fundamental weakness of organizationand managementtheorythe so-calledrelevancegap betweentheoryandpractice. and management That is, organization theory tends to or relevantto practitioners be not obvious (e.g., Beyer

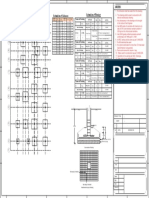

andTrice1982, Hambrick 1994, Huff2000, Miner1997, Priemand Rosenstein2000). Table 1 providesa conceptualframework defines that the main differencesand complementarities science, of humanities,and design as three ideal-typicalmodes of engaging in organizationalresearch. This framework of providesthe settingfor the remainder this paper. This paperwill focus on the differencesand synergies between organizationscience and design; referenceto the humanitiesperspectivewill be made merely in the

Table 1 Three Ideal-TypicalModes of Engaging in OrganizationalResearch Science Purpose: Humanities Design Produce systems that do not yet exist-that is, change existing organizational systems and situationsinto desired ones. Design and engineering(e.g., aeronautical architecture, engineering, computerscience).

Understandorganizational understand,and critically phenomena, Portray, on the basis of consensual objectivity, reflecton the humanexperience of actors inside organized by uncoveringgeneral patternsand forces that explainthese practices. phenomena. Naturalsciences (e.g., physics) and other disciplines that have adopted the science approach (e.g., economics). Our Representational: knowledge the worldas it is; nature represents of thinkingis descriptiveand analytic. Morespecifically,science is characterizedby (a) a search for general and valid knowledge and in (b) "tinkering" hypothesis formulation testing. and Humanities (e.g., aesthetics, ethics, hermeneutics,history,cultural studies, literature, philosophy).

Role Model:

Viewof Knowledge:

Natureof Objects:

Organizational phenomena as empiricalobjects, withdescriptive and well-definedproperties, that can be effectivelystudied froman outsider position.

Constructivist narrative: and All Pragmatic: Knowledgein the arises fromwhat actors service of action; natureof knowledge thinkand say about the world; and thinkingis normative natureof thinkingis critical synthetic. and reflexive. Morespecifically,design assumes each situationis uniqueand it draws on purposes and ideal solutions,systems thinking, and limitedinformation. Moreover, it emphasizes participation, discourse as mediumfor and intervention, pragmatic experimentation. Discourse that actors and issues and systems Organizational researchersengage in;appreciatas artificial objects withdescriptive as well as imperative(ill-defined) ing the complexityof a particular discourse is given precedence nonroutine properties,requiring over the goal of achieving action by agents in insider general knowledge. positions. Imperative properties also draw on broaderpurposes and ideal target systems. Does an integratedset of design Key question is whethera certain humanexperience(s) propositionsworkin a certain (category of) in an organizational ill-defined(problem)situation? setting is etc. The design and developmentof "good,""fair," new (states of existing) artifacts tends to move outside boundaries of initial definition the situation. of

Focus of Theory Discoveryof general causal Development: relationships among variables (expressed in hypothetical statements):Is the hypothesis valid? Conclusionsstay withinthe boundariesof the analysis.

ORGANIZATION SCIENCE/Vo1. 14, No. 5,

2003 September-October

559

A. GEORGESL. ROMME Organization Design as

context of its criticism on science. This is not to say that the humanitiesare only important the sciencefor humanitiesdebatein organization studies.As is evident from Table 1, the humanitiesserve as one of threekey modes of engaging in organizational research;each of these threemodes is essentialto the pluralistic natureof the field of organization studies.The futuredevelopment of organizational researchlargely dependson building interfacesfor communication collaboration and between these threemodes. This paper focuses on the science-designinterface becausethe relevancegap betweentheoryandpracticeis most likely to be bridgedby discussingdifferencesand between the mainstreamscience's complementarities and (practitioner's) design mode. Moreover,the debate betweenthe science and (postmodern) humanities camps appears to have turned our attentionaway from the issue of researchobjectivesand our commitimportant ments as scholars.In this respect,the pragmatism the of mode has also been describedas the common design sense-on which science ground-in an epistemological andhumanities meet (Argyriset al. 1985,Wicksand can Freeman1998). The frameworkin Table 1 also suggests some differences in terminology.When discussing the science mode, I will refer to organizational systems as empirical objects with descriptiveand well-definedproperand ties, whereasartificialobjectswith both descriptive serveas objectsof designresearch. imperative properties That is, science and design may focus on the same kind of objects,but do so fromdifferentepistemological positions. The argument organizedas follows. First,I explore is science from the representational organization perspective as well as from more recently developed underI standingsof the practiceof science. Subsequently, discuss and developthe notionof design moreextensively; in this section I also explore how and why the design disciplineshave largely moved away from academiato other sites in the economy.The first and thirdcolumns in Table 1 anticipate summarize argument and the about science and design to this point in the paper. The argument then turnsto the genealogy of design and studies. methodologiesin organization management servesto illustrate Next, the circular designmethodology the latest generationof design approaches organizain tion studies.Finally,I explorethe implications organiof zationalresearchat the interfaceof science and design, and proposea framework developingresearchat this for interface(see Table2 for a preview).

560

Organization Science as Ideal-Typical Mode of Research

Purpose Science develops knowledge about what already is, by discoveringand analyzing existing objects (Simon 1996). It is based on several key values, particularly disinterestednessand consensual objectivity. Disinterestedness implies that scientistsare constrained to protectthe production scientific knowledgefrom of bias and other subjectiveinfluences (Merton personal can 1973, Ziman 2000). Because researchers never be cleansed of individualand other interests, completely science thereforestrives to attainconsensualobjectivity, that is, a high degree of agreementbetween peers (Pfeffer 1993, Ziman2000). This implies that organization science,in its ideal-typical form,strivesfor consensualobjectivity researching understanding in and general patternsand forces thatexplainthe organizedworld. Role Model and View of Knowledge Mainstream "science"is based on the idea organization that the methodology of the natural sciences should and can be the methodologyof organizationscience. This approach assertsthatknowledgeis representational in nature (Donaldson 1985, 1996), and assumes that our knowledgerepresentsthe world as it is. The key researchquestionis thus whetheror not generalknowledge claims are valid. As a result, the natureof thinkscience tends to be descriptiveand ing in organization analytical. Nature of Objects pheKnowledgeclaimsin sciencereferto organizational nomena as empirical objects with descriptiveproperties. Organization science assumesorganizational order to be empiricallymanifestedas a set of stable regularities that can be expressedin the form of hypothetical statements.These statementsare usually conceived as namely as a set revealingthe natureof organizations, of objective mechanismsunderlyingdiverse organizational realities(Donaldson1985, 1996). This approach can (implicitly)assumesthese objectivemechanisms be most effectively studied from an unbiased "outsider" position. Focus of Theory Development science tends to focus on the discovery Organization of generalcausal relationships among variables.These causalities can be rather simple ("If x and y, then z"). Because variationsin effects may be due to other causes than those expressed in a given proposition,

ORGANIZATION 2003 14, SCIENCE/Vol. No. 5, September-October

A. GEORGES L. ROMME

Organization as Design

the actualoperationsof scientificinquiryare construcand tive ratherthanrepresentational, are embeddedin a social process of negotiationratherthan following the (individual)logic of hypothesis formulationand testing (Latour and Woolgar 1979, Knorr-Cetina1981). Knorr-Cetina (1981) suggeststhe conceptof "tinkering" to describe and understand what she observed in the naturalsciences: Tinkerersare "awareof the material opportunities they encounterat a given place, and they exploit themto achievetheirprojects.At the same time, they recognize what is feasible, and adjustor develop their projects accordingly.While doing this, they are some constantlyengaged in producingand reproducing kind of workableobject which successfully meets the settledon" (Knorr-Cetina purposethey have temporarily 1981, p. 34; see also Knorr1979). More recently, work by Gibbons et al. (1994) has motivateda numberof authorsto advocatethat organization and management studies should be repositioned from researchthat is discipline based, universitycentered, and focused on abstractknowledge toward socalled Mode 2 research(Huff 2000, Starkeyand Madan 2001, Tranfieldand Starkey 1998). Mode 2 research, which appearsto be characteristic a numberof discito plines in the appliedsciences and engineering,focuses on producingknowledgein the context of application and is transdisciplinary: Potentialsolutions arise from the integration different of skillsin a framework appliof cation and action, which normallygoes beyond that of any single contributing discipline(Gibbonset al. 1994, Tranfieldand Starkey 1998). Mode 2 researchis heterogeneousin terms of the skills and experiencepeoand ple bringto it. In addition, accountability sensitivity to the impact of the researchis built in from the start Criticism of Science as Exclusive (Ziman 2000). In this respect, Mode 2 researchdraws Mode of Research some writersexplicitlycriti- on the humanitiesto built reflexivityinto the research Drawingon the humanities, cize the representational natureof science-basedinquiry process (Gibbonset al. 1994, Nowotnyet al. 2001). The proposalfor Mode 2 researchhas been debated (e.g., Gergen 1992, Tsoukas 1998). Others express severe doubts about whether the representational and in a special issue of the BritishJournalof Management constructivist view arereallyincompatible (Czarniawska (e.g., Grey 2001, Hatchuel 2001, Hodgkinsonet al. Elsbachet al. 1999, Tsoukas2000, Weiss 2000). 2001, Huff and Huff 2001, Weick 2001). For example, 1998, This debate on the natureof knowledgehas primarily Hatchuel(2001) suggeststhatMode 2 researchrequires of addressedepistemologicalissues and has turnedatten- two essentialconditions:(1) a clarification the scientific object of management researchand (2) the design tion away from the issue of researchobjectives, that of partnerships academicsandpracresearchers of research-oriented is, from our commitmentsas organization titioners.Weick (2001) arguesthat the "relevance" gap (Wicksand Freeman1998). is as much a productof practitioners studiesof how researchis actuallydone in being wedded to Moreover, the naturalsciences have been undermining science as gurusandfads as it is the resultof academics being wedthe (exclusive) role model for organizational research. ded to science.He suggeststhatthis gap persistsbecause egopractitioners forget that the world is idiosyncratic, Anthropologicalstudies of how research in some of the naturalsciences actually comes about suggest that centric,and uniqueto each personand organization. causal inferencesare usually expressedin probabilistic equationsor expressions(e.g., "X is negativelyrelated to y"). This concept of causalityhelps to explain any but observableorganizational phenomena, in itself cannot accountfor qualitative novelty (Bunge 1979, Ziman therefore Conclusionsand any recommendations 2000). of have to stay withinthe boundaries the analysis. The following researchmethodsare frequentlyused in organization science: The controlled experiment, field study,mathematical simulationmodeling,and case In controlledexperiments, researchsettingis the study. of fromthe constraints disturbances the and safeguarded practicesetting,andthus a limitednumberof conditions can be variedin orderto discoverhow these variations affect dependent variables (e.g., Sarbaugh-Thompson and Feldman 1998). In the field study, also known as the naturalexperiment,the researcher gathersobservations regardinga numberof practicesettings, measuring in each case the values of relevant (quantitative or qualitative) the variables;subsequently data are analyzed to test whether the values of certain variables are determinedby the values of other variables(e.g., Eisenhardtand Schoonhoven 1996, Kraatz and Zajac modelsimulation 2001, Wageman 2001). Mathematical involvesthe study of complex cause-effectrelationing of ships over time;this requiresthe translation narrative to enablethe researcher to a mathematical model, theory to develop a deep understanding complex interacof tions amongmanyvariables overtime (e.g., Rudolph and case the single or comparative Repenning 2002). Finally, to of studyhelpsresearchers graspholisticpatterns orgain real settings(Numagami1998). nizational phenomena

ORGANIZATION 2003 14, SCIENCE/Vol1. No. 5, September-October 561

as A. GEORGESL. ROMME Organization Design

is research betTheseideas suggestthatorganizational ter capturedand guided by more pluralisticand sensitive methodologiesthan by exclusive images of how In science shouldbe or is actuallypracticed. this respect, no discipline or method of inquiry has a monopoly on wisdom in the social sciences, because there is no way to determinewhat constitutes "better"forms of or meaningcreation,in eitherthe epistemological moral sense (Fabian2000, Heller 2001, Wicks and Freeman 1998, Ziman 2000). Moreover,knowledge acquisition a to withregard broadandcomplexissues requires close, between the variety of issues isomorphicrelationship researched,and a requisite variety of researchmodes to engage with them (Heller 2001). Thus, I suggest the studiesincludes at core of organization epistemological modes of researchthat least threedifferentideal-typical cannotreadilybe reducedto a single privilegedculture of inquiry(see Table 1).1 In the following sections, we respondto the need for Mode 2 researchby means of a separateideal-typical"design"mode of engaging in the research,ratherthan by compromising ideal-typical notionof science.

Design as Ideal-Typical Mode of Research

This section describesthe natureof design research,in comparisonwith science, and also describeshow and why the design disciplineshave moved away from the academiccommunityto othersites in the economy. Purpose In The Sciences of the ArtificialHerbertSimon (1996) argues that science develops knowledge about what alreadyis, whereasdesign involveshumanbeings using knowledgeto createwhat shouldbe, things that do not yet exist. Design, as the activity of changingexisting situationsinto desiredones, thereforeappearsto be the core competenceof all professionalactivities. Role Model says Simon (1996), the Historicallyand traditionally, and sciencesresearch teachaboutnatural things,andthe with artificial things,includdisciplinesdeal engineering ing how to designfor a specifiedpurposeandhow to creThe social ate artifactsthat have the desiredproperties. viewed the naturalsciences sciences have traditionally as their main referencepoint. However,Simon argues that engineersare not the only professionaldesigners, because"everyone designswho devisescoursesof action ones. into aimedat changingexistingsituations preferred The intellectualactivitythat producesmaterialartifacts

562

from the one that preis no differentfundamentally scribesremediesfor a sick patientor the one thatdevises a new sales planfor a companyor a social welfarepolicy for a state"(Simon 1996, p. 111). Simon (1996) also describeshow the naturalsciences almost drove the sciences of the artificialfrom proin fessional school curricula-particularly engineering, business,and medicine-in the first20 to 30 years after factordrivingthis process WorldWarII. An important schoolsin businessandotherfields was thatprofessional when design approaches cravedacademicrespectability, were still largely "intuitive,informaland cookbooky" (Simon 1996, p. 112). In addition,the enormousgrowth of the higher education industry after World War II of createdlargepopulations scientistsandengineerswho the economy and took over jobs fordispersedthrough merly held by techniciansand otherswithoutacademic degrees(Gibbonset al. 1994). This meantthatthe numworkin the areasof design ber of sites wherecompetent and engineeringwas being performedincreasedenorthe mously,whichin turnundermined exclusiveposition of universitiesas knowledge producersin these areas (Gibbons et al. 1994). Another force that contributed to design being (almost) removed from professional of was school curricula the development capitalmarkets offering large, direct rewardsto value-creatingenterprises(BaldwinandClark2000). In otherwords,design and in the technicalas well as managerial social domains moved from professionalschools to a growing number of sites in the economy where it was viewed as and morerespectable whereit could expect largerdirect economicrewards. View of Knowledge Design is based on pragmatism as the underlying epistemological notion. That is, design research develops knowledge in the service of action; the and natureof designthinkingis thusnormative synthetic in nature--directedtowarddesired situationsand systems and toward synthesis in the form of actual actions. The pragmatismof design research can be expressed in more detail by exploring the normative ideas and values characterizing good practice in professions such as architecture, organization development, and communitydevelopment.These ideas and values are defined here; several ideas described by Nadler and Hibino (1990) have been adaptedand extendedon the basis of the work of others; three additionalvalues and ideas-regarding participation, discourse, and experimentation-have been defined on the basis of other sources, includingmy own work. The first three values and ideas definethe contentdimensionof design

ORGANIZATION 14, SCIENCE/Vo1. No. 5, September-October 2003

as A. GEORGESL. ROMME Organization Design

Participation and Involvement in Decision Making inquiry: (1) each situation is unique; (2) focus on Those who carryout the solution purposes and ideal solutions; and (3) apply systems and Implementation. should be involved in its developmentfrom the beginthinking. Involvementin makingdecisions about solutions Each Situation is Unique. This assumptionimplies ning. and theirimplementation leads to acceptanceand comthat no two situationsare alike; each problemsituation mitment (Vennix 1996). Moreover,getting everybody in is uniqueandis embedded a uniquecontextof related involved is the best strategy if one wants long-term problems,requiringa unique approach(Checklandand and community (Endenburg1998, Scholes 1990, NadlerandHibino 1990). The uniqueand dignity, meaning, Weisbord1989). In some cases, the benefitsof particiembeddednatureof each situationmakes it ill defined, in than solutionscan be more important or wicked, which means that there is insufficientinfor- pation creating the solutionitself (Romme 1995, 2003). mationavailableto enablethe designerto arriveat solutions by transforming, the Discourse as Medium for Intervention. For design optimizing,or superimposing given information (Archer1984). professionals, languageis not a mediumfor representing in the world,but for intervening it (Argyriset al. 1985). Focus on Purposesand Ideal Solutions. Focusingon Thus, the design process should initiate and involve purposeshelps "stripaway"nonessentialaspectsof the dialogue and discourse aimed at defining and assessproblem situation. It opens the door to the creative ing changes in organizationalsystems and practices emergenceof largerpurposesand expandedthinking.It and Scholes 1990, Warfieldand Cardenas also leads to an increase in consideringpossible solu- (Checkland tions, and guides long-termdevelopmentand evolution 1994). et Pragmatic Experimentation. Finally, pragmatic exper(Banathy1996, Nadlerand Hibino 1990, Tranfield al. 2000). If an ideal targetsolution can be identifiedand imentationis essential for designing and developing agreed upon, this solution puts a time frame on the new artifacts,and for preservingthe vitality of artiearlier(Argyris1993, solutions,and facts developedand implemented systemto be developed,guides near-term infuses them with larger purposes."Even if the ideal Banathy 1996). Pragmaticexperimentation emphasizes of with new ways of orgalong-termsolutioncannotbe implemented immediately, the importance experimenting certainelements are usable today"(Nadlerand Hibino nizing and searchingfor alternative more-liberating and forms of discourse(Argyriset al. 1985, Romme 2003, 1990, p. 140). WicksandFreeman1998).This approach necessary is to Apply Systems Thinking.Systems thinking helps conventional wisdomandask questionsabout "challenge that every unique problem is designers to understand own 'what if?' but it is temperedby the pragmatist's embeddedin a largersystemof problems(Argyriset al. commitmentto finding alternatives which are useful" 1985, Checklandand Scholes 1990, Vennix 1996). It (Wicksand Freeman1998, p. 130). helps them to see "not only relationshipsof elements Some of these ideas are familiarto otherapproaches. and theirinterdependencies, most importantly, but, pro- For example, the notion of discourse is shared with vides the best assuranceof includingall necessaryele(Gergen 1992), althoughthe lattermay ments,thatis, not overlookingsome essentials"(Nadler postmodernism not supportthe underlyingnotion of pragmatism (see and Hibino 1990, p. 168). Table 1). The importanceof participation involveand Fourotherideas definethe values and ideas regarding ment is also emphasizedin the literature participaon the processof design:(1) limitedinformation; partic(2) tive management empowerment and (Romme1995).The ipationand involvementin decision makingand imple- notion of is also centralto laboratory experimentation and mentation; discourseas mediumfor intervention; (3) experimentsin the naturalsciences and (some partsof experimentation. (4) pragmatic the) social sciences;however,experiments designers by LimitedInformation.The availableinformation about in organizational settings are best understood as action situation(or system)is by definitionlimited; experiments (Argyris et al. 1985), rather than as conthe current in the contextof a design project,this awareness guards trolled experiments in a laboratory setting. In response to the need for more relevant and actionagainst excessive data gatheringthat may participants make them expertswith regardto the existing artifacts, able knowledge, organization researchers tend to adopt whereasthey should become expertsin designing new action research methods to justify a range of research ones. Too muchfocus on the existingsituationmay pre- methods and outputs. Action research has been, and still vent people fromrecognizingnew ideas and seeing new is, not well accepted on the grounds that it is not normal science (Eden and Huxham 1996, Heron and Reason ways to solve the problem(Nadlerand Hibino 1990). 2003 ORGANIZATION 14, SCIENCE/Vol1.No. 5, September-October 563

A. GEORGESL. ROMME Organization Design as

1997, Tranfieldand Starkey 1998). Action researchers have been greatly concernedwith methodsto improve the rigor and validityof theirresearch,in orderto gain in actionresearchers this academiccredibility. Moreover, area have emphasizedretrospective problemdiagnosis morethanfindingand creatingsolutions(e.g., Eden and Huxham1996).Design research severalkey incorporates ideas from action research,but is also fundamentally differentin its future-oriented focus on solutionfinding. Nature of Objects issues and systems Design focuses on organizational as artificialobjects with descriptiveas well as imperative properties,requiringnonroutineaction by agents also in insiderpositions.The imperative properties draw on broader purposesand ideal targetsystems.The pragmaticfocus on changingand/orcreatingartificial objects ratherthan analysis and diagnosis of existing objects makes design very differentfrom science. The novelty of the desired (situationof the) system as well as the natureof the actions to be takenimply that nonroutine the objectof design inquiryis ratherill defined. Focus of Theory Development The key questionin design projectsis whethera particuin lar design"works" a certainsetting.Sucha designcan be based on implicitideas (cf. the way we plan most of in ourdaily activities).However, case of ill-definedorganizationalissues with a huge impact, a systematicand disciplinedapproachis required(Boland 1978). A systematic and disciplinedapproachinvolves the development and applicationof propositions,in the form of a coherent set of related design propositions.Design propositionsare depicted,for example, as follows: "In situationS, to achieve consequenceC, do A" (Argyris 1993, Argyriset al. 1985). and In case of an ill-definedcurrent desiredsituation, a design approachis requiredthat cannot and should not stay within the boundariesof the initial definition of the situation.Archer(1984, p. 348) describesan illas definedproblemas "one in which the requirements, do not containsufficientinformation enablethe to given, designerto arriveat a means of meetingthose requirements simply by transforming, reducing,optimizing,or the alone."Ill-defined superimposing given information issues are, for example,lack of communication coland laboration betweenteam membersor differentorganizaas tional units; nonparticipation the typical responseof programsinitiatedby manemployees to participation agement;and the securityof commercialairlineflights with regard to new forms of terrorism.By contrast, well-definedproblemsare, for example,determining the

564

level for a particular business;selectoptimalinventory from a pool of applicants the on ing the best candidate basis of an explicit list of requirements; computing and a regressionanalysisof a certaindependentvariableon a set of independent controlvariables(Newell and and Simon 1972). When facedwith ill-definedsituations challenges, and a solution-focusedapproach.They designers employ begin generatingsolution concepts very early in the design process,because an ill-definedproblemis never going to be completelyunderstoodwithout relatingit to an ideal targetsolutionthat brings novel values and purposesinto the design process (Banathy1996, Cross 1984). Accordingto Banathy(1996), focusing on the system in which the problem situation is embedded tendsto lock designersinto the current system,although design solutionslie outside of the existing system: "If solutions could be offered within the existing system, therewould be no need to design. Thus designershave the to transcend existing system. Theirtask is to create a differentsystem or devise a new one. That is why designerssay they can trulydefine the problemonly in light of the solution.The solution informsthem as to what the real problemis" (Banathy1996, p. 20).

Since the mid-1970s design methodologieshave been developing.The firsteditionof Simon'sTheSciences of in the Artificial,published 1969 (Simon 1996), was parinfluential the development systematic in and of ticularly formalizeddesign methodologiesin architecture, engiscience medicine,andcomputer neering,urban planning, (e.g., BaldwinandClark2000, Cross 1984, Jacksonand Keys 1984, Klir 1981, Long and Dowell 1989, Warfield 1990). with these disciplines,the notionof design Compared is less establishedin the currentstate of the art of organization theory.This has not always been the case. In this respect,three generations design methodoloof for organizationand managementcan be distingies guished.The firstgeneration developedin the late 1800s and early 1900s and culminatedin the work of the engineerFrederick Taylor(1911), whose work was initially publishedand discussedonly in engineering journals (Barleyand Kunda1992). Knownas the "scientific arose movement,these design approaches management" from attempts by managers with engineering backgroundsto applythe principlesof theirdisciplineto the of The organization production. core of these approaches involved specific schemes and practicesfor improving

Genealogy of Design Methodology in Organization Studies

ORGANIZATION 2003 SCIENCE/Vol. No. 5, September-October 14,

as A. GEORGESL. ROMME Organization Design

in controland coordination, particularly the managerial controlsysareaof cost accountingsystems,production tems, andwage payment plans(BarleyandKunda1992). The second generationof design methodologiesin organizationand managementfocused on regulatory such as sociotechnical systems,functionalist approaches and humanrelations(Checkland1981, systems theory, Drucker 1954, Emery and Trist 1972, Jaques 1962). Similar to the first generationof design approaches, the primaryconcern of the second generationwas to seek universaldictumsthat managerscould employ in the course of their work (Burrell and Morgan 1979). However, unlike their predecessors,the new design approachesdescribed and codified general processes thanspecifictools and practices-for example,in rather the areaof setting objectives,planning,and forecasting (Barleyand Kunda1992). of Morerecently,a thirdgeneration design thinkingis is This categoryof design approaches increasemerging. ingly groundedin explicitly stated philosophicaland theoretical by positions,characterized a co-evolutionary, Examvalue-laden,and ethics-basedsystems approach. educafor ples includedesignmethodologies organizing tion (Banathy1996, 1999; Romme 2003; SchOn1987), for groupmodel building(Vennix 1996), and for teamwork in business organizations(Tranfieldet al. 1998, (1998) has pioneeredthe 2000). In Europe,Endenburg for of a system'sdesign methodology orgadevelopment nizations (see also, Romme 1999). The latter design methodologywill be exploredin more detail in the next section. have developeda well-known Argyrisand co-authors in the area of organizational learndesign methodology ing and defensive behavior (e.g., Argyris et al. 1985, Argyris and Schbn 1978). This methodology "begins with a conception of human beings as designers of action"(Argyriset al. 1985, p. 80) and involves a tool for interventionin so-called limited learning systems. A model of effective learningsystems guides interventions in these limited learningsystems. The model of effective learning systems guides the researcheras an interventionist-that is, he intends to produce action the consistentwith this model to interrupt counterproductive features of the limited learning system (e.g., Argyris 1993, Argyris and Kaplan 1994, Argyris and Sch5n 1978, Argyriset al. 1985, Schwarz1994). of as Particularly a resultof the firstgeneration design methodologies,the conceptof design is easily misinterconcept used preted as being a technical,instrumental under by managerstrying to bring their organizations rationalcontrol.This oldernotionof design is no longer in useful and relevant.In the second, and particularly

ORGANIZATION 14, SCIENCE/Vol1. No. 5, September-October 2003

of are the thirdgeneration designthinking,managers not Their viewed as all-powerful architects organizations: of is assumedto be influenceon organizational processes in limited,becausethey are not the only participants the discursiveandcollaborative thatshapeorganiprocesses zationalsystems (Banathy1996, Endenburg 1998).

This section describesthe developmentand application I of the circulardesign methodology. have selected this because it is groundedin explicit theoretical example frameworks and has been tested in a large numberof organizations. The circular organizationaldesign, pioneered by Gerard Endenburg,aims at the creation of learning ability by active participationat the organizational level as well as at the group and individual levels. started developthis design approach the to in Endenburg early 1970s, when he was CEO of an electrotechnical In companyin The Netherlands. this company,he was confronted with problemssuch as the functioning the of workscouncil thatdid not appearto provideany opportunitiesfor effective consultation between management and employees, but instead, frequentlygeneratedconflicts. Inspiredby the notion of circularityfrom systems theory as well as the idea of consensus decision making practicedin Quakerorganizations, Endenburg startedexperimenting with a so-calledcirculardesign to solve the problemof employeeparticipation involveand ment (Endenburg1998, Romme 1999). At this early and stage, the notionsof circularity consensusservedas ratherbroadand ill-definedideal targetsthat helped to define the currentsituationregarding employee particiand pation;thatis, the prevailingauthority powerstructureas well as decision-making practicein the company were perceivedas roadblocks any attempt increase to to participation. In the firstfew years,experiments were set up in collaborationwith other managersand employees within the company;later outsidersstartedparticipating the in further of the circular andits impledevelopment design mentationprocess. This has led to a well-developed approach,which essentially implies that the organization's abilityfor effective learningand decision making at all levels is increasedby addinga so-called circular to structure the existing (usually) hierarchical structure (Romme 1999). This design approachinvolves a numberof design rules, defining how decisions should be made, how different decision-makingunits are to be linked, and

565

The Case of Designing Circular Organizations

A. GEORGESL. ROMME Organization Design as

so forth.2These rules are formulatedin terms of, "to achieve A in situationS, do D." For example,one of the rules is as follows: To achieveeffectiveimplementation of and commitment decisionsaboutpolicy issues to in a groupof people authorized do so, decisions are to taken on the basis of consent (defined as "no argued that objection"); is, a decision is madeif and only if all participants consent(Endenburg give 1998). These rules are laid down in the company'sstatutes, as a set of permanentrules safeguardingthe parat ticipation of all stakeholdersand shareholders the boardlevel and managersand employeesat otherlevels in the organization.The circular design method also includes tools in the area of setting objectives, organizing and managing work, performanceassessment, and performance-based at compensation the individual, levels (Endenburg 1998). Case group,andorganizational studiesof severalfirmsthat have redesignedtheirorganization on the basis of the circular model suggest that decision makingand learningproceedsmore easily and effectively with ratherthan without this redesign (Romme 1999, VanVlissingen 1991). in own comSince the firstexperiments Endenburg's in the early 1970s, the circular model now pany appears to have progressedbeyond the experimental stage. It is currentlybeing used in about 30 organithe zations throughout world includingBrazil, Canada, The Netherlands, the United States (Romme 1999, and RommeandReijmer1997, VanVlissingen1991). Dutch firms, requiredby law to install one or more work if councils, are exempted from this requirement they have implementedthe circularmodel (Romme 1999). solutionhas Thus, the circulardesign as an ideal-target been tested in an increasingnumberof organizational practices.Elsewhere,the details of the circulardesign in have been describedand grounded systems approach Romme 1995) and organiza1998, theory (Endenburg tion theory(Romme 1997, 1999). The way in which the circularmodel serves as an ideal-targetsystem in the design process can be illustrated as follows. Very early in the design process in an organization,typically with help of external conuses the circulardesign rules sultants,the organization to define the nature of problems and challenges it is facing (Romme and Reijmer 1997). For example, in a first session with the executive team of a large catering services firm, the imperativesfor and direction of organizational change were explored.The executives initially defined these imperativesin terms of low commitmentto and involvementof their employin ees andmiddlemanagement servicequalityprograms,

566

which had been set up to improvethe firm's competitive position. The consultantthen introducedthe circular system as an ideal-targetsolution, and invited the executives to frame and understand problems the were facing in terms of this ideal-typicalsystem. they The executives subsequently reframedthe existing situation in their organization terms of a lack of susin tained opportunities participation, well as their for as to own mistrustin delegatingauthority local managers. In this respect,their initial problemdefinitionwas perbut ceived to be not "wrong," incompleteand superficial. The executive team subsequentlystarteda longterm effort to develop a tailor-madesolution, drawing on the design rules that constitutecircularorganizsystem, to decentralizedecision ing as an ideal-target making to the people closest to the customerand at the lowest level possible in view of the decision issue (RommeandReijmer1997). These and othercases suggest that the circularmodel as an ideal-targetsystem the serves to define and understand existing organizational situationfroma moresystemicpoint of view, and focus on symptoms broadenand deepenthe managerial Romme 1999, Rommeand andevents(Endenburg 1998, Reijmer1997, VanVlissingen 1991). The development and application of the circular design illustratessome of the key elementsand characteristicsof the design mode of engagingorganizational research.The circularmethodologyacknowledgesthe ill-definedand embeddednatureof organizational probsolutions, lems, and uses broaderpurposes,ideal-target and systems thinking(combinedin an ideal-target sysdevelopment. tem), to guide long-term organizational In the early stages of developingthe methodology,the ideal-targetsystem was itself ill defined-in terms of broadconcepts such as circularity. means of a variBy ety of pragmaticexperimentsin which these concepts were specified,applied,and tested, a detailedand codified methodology graduallyarose. this methodologyappears focus on findto Moreover, ratherthan on extensive analysis of the ing solutions, currentsituation.It also emphasizesand enablesparticipationby people involved.In this paper,I will not deal with the (scientific)questionof whetheror not circular betterthanothers.At this pointit is sufdesignsperform to ficientto observethatcircular designsappear "work," that is, producesatisfactory outcomes for a population of professionalsother than the pioneers (e.g., Romme 2003, RommeandReijmer1997, VanVlissingen 1991). The focus on solutions, envisioned with help of broader purposesand ideal-target systems,characterizes the circular Mainstream sciencein the area methodology.

ORGANIZATION 14, SCIENCE/Vol1. No. 5, September-October 2003

A. GEORGES L. ROMME

Organization as Design

studies would suggest a focus on anaof organization which in the andunderstanding existingsituation, lyzing itself would not lead to any changesin the directionof a novel situationor system.

is integration not desirablebecauseno mode of research has a monopolyon wisdom.

Toward an Interface Between Design and Science If design and science need to co-exist as important modes of engaging in organizationalresearch, any the Design-Science Interface to Developing attempt reducethe relevancegap betweenmainstream This section explores the implicationsof positioning theories and the world of practice (see Introduction) researchat the interfaceof science and startswith developingan interfacebetween design and organizational for and describesa framework developingthis science. A key element of the interfaceproposedhere design, interface(see Table2). involvesthe notion of design propositions. Design propositions,as the core of design knowlTwo Concepts of Causality edge, are similarto knowledgeclaims in science-based science is the research, irrespectiveof differences in epistemology The concept of causality underpinning of varianceamongvariablesacrosstime or space, and notions of causality.These design propositions can study that is, the linkage of a known empiricalphenomenon provide a sharedfocus for dialogue and collaboration into a wider networkof data and concepts. Thus scibetween design and science. In this respect,Van Aken derivedfrom (2004) argues that a design science for management ence tendsto focus on testingpropositions of generaltheories(Markusand Robey 1988, Mohr 1982, researchshouldfocus on the development tested and Ziman2000). groundedrules. Drawing on Bunge (1967), he argues between science and design Design draws on what Argyris (1993, p. 266) calls that effective partnerships design causality to produce knowledge that is both in the technical domain lead to tested technological actionableand open to validation.The notion of design rules groundedin scientific knowledge-for example, and straight- the design rules for airplane wings being tested in causality appearsto be less transparent forward than the concept of causality underpinning engineeringpractice as well as groundedin the laws and science-involving the study of variance among and empiricalfindingsof aerodynamics mechanics variables(see Table2). This is becauseof two character- (VanAken 2004). VanAken (2001) recommends sima istics of design causality. First,design causalityexplains ilar approachto testing and groundingdesign rules in how patternsof varianceamong variablesarise in the managementresearch. He argues that testing should firstplace, and in addition,why changeswithinthe pat- involve both alpha and beta testing, notions adopted tern are not likely to lead to any fundamental changes from softwaredevelopment.Alpha testing involves the For example,both the hierarchical com- initial development of a design proposition, and is (Argyris1993). mand structureand the circular structure(see previ- done by the researchers themselvesthrougha series of in ous section) model a certaincategory of structures cases. Subsequently, beta testing is a kind of replicaare which organizational processesand patterns embed- tion researchdone by third partiesto get more objecded. Each structuredefines a relatively invariantpat- tive evidence as well as to counteractany blind spots not tern of values, action strategies,group dynamics, and or flaws in the designpropositions acknowledged by outcomes. the researchers Aken 2001). (Van This suggeststhatresearchat the design-scienceinterSecond, when awarenessof a certainideal-target system (e.g., the circulardesign) has been created,design face should focus on design propositions developed contextsas well as grounding causality implies ways to change the causal patterns. through testingin practical That is, ideal-target can inspire, motivate,and in the empiricalfindingsof organization science. This systems enable agents to develop new organizational of researchwouldenablecollaboration betweenthe processes type and systems.Both Argyris(1993) andEndenburg and science mode, while it would also respect (1998) design differencesbetweenthe two emphasize,however,thatthe causalityof the old andthe some of the methodological or modes. Table 2 outlines how design propositionsare new structure co-exist, long aftera new program will structure been introduced. has redefinedinto hypothesesthat can be empiricallytested in the science mode, and vice versa-how hypotheses These two characteristics design causalitytend to of in in and complicatethe development testingof designpropo- grounded empiricalevidenceare translated prelimsitions as hypothesesin science. A full integrationof inarydesign propositions. At the interfacebetween science and design, some the design and science modes is thus not feasible; this made earlierin this paperthat research methods appear to be more effective than reinforcesthe argument

ORGANIZATION 14, SCIENCE/Vo1. No. 5, September-October 2003 567

A. GEORGES L. ROMME

Organization as Design

Table 2 Frameworkfor Creating Synergy and Collaboration Between Design and Science Design Mode CausalityConcept Design causality:Study of how relatively invariant patternsarise, and of ways to change these patterns,to produce knowledge that is actionable as well as open to validation, Design propositionsreferto variablesas well as,relativelyinvariant patterns(with descriptiveas well as imperativeproperties), for example: "In to achieve O, do A." S, Several design propositionstend to be part of a coherent set. Science Mode Variancecausality:Studyof cause-effect relationshipsby analyzingvarianceamong variablesover time and/or space, to produce knowledgethat is general and consensually objective in nature. to Propositions/hypotheses, referring variables withdescriptiveproperties,are typically formulated follows. "Ifx, then y" or "x is as neg/pos relatedto y." Each hypothesis is tested on the basis of data regardingthe relevant(includingcontrol) variablesmeasured.

InterfaceBetween Design and Science

Empirical findings obtained for hypotheses in the science mode are reformulated (preliminary) into design propositionsas follows. * If necessary, redefine descriptive(properties of) variables into imperativeones (e.g., actions to be taken). * Redefinethe probabilistic natureof a hypothesis into an action-oriented design proposition. * Add any missing context-specificconditions and variables (drawingon other researchfindings obtained in science or design mode). * In case of any interdependenciesbetween formulatea set of hypotheses/propositions, propositions.

Propositionsdeveloped and tested in the design mode can be reformulated hypotheses as into follows. * Redefine imperative (propertiesof) variables into descriptiveones. * Redefineaction-oriented design propositions statements (if necessary, on a into probabilistic more aggregate level). * Add any variablesthat are implicitin the insiders'perspective (e.g., by drawingon previousresearch). Forexample, the design proposition,"In to S, as achieve O, do A,"can be rewritten follows: "For agents intendingto achieve O in S, action A is positivelyrelatedto resultR." Ifdesign as propositionsare formulated a set of related propositions,then science testing should aim at both each individual hypothesis and the set as a whole.

Research Methods at the Interface: (1) Alphaand beta testing of design propositionsby means of action experimentsand comparativecase studies (both based on experimentalreplication logic) (2) Simulation by modelingof the currentand ideal target system, particularly means of methods (e.g., system dynamics modeling) integratedsimulation (3) Incase of (1) and (2), but also when other methods are applied, a combined insider-outsider approach facilitatesdevelopmentof design propositionsgrounded in organization science and tested in professionalpractice.

others. The nature of alpha and beta testing of design propositions by means of action experiments is highly

similar to the replicationlogic recommended comfor case studies(Eisenhardt 1989, Numagami1998, parative

Yin 1984). Thus, the collaboration between researchers

in insider roles (e.g., internal consultants) who adopt the method of action experiments and academic researchers in outsider roles employing a comparative case method is less likely to suffer from differences in, for example, notions of causality between design and science.

568

ORGANIZATION 14, SCIENCE/Vol1. No. 5, September-October 2003

A. GEORGES L. ROMME

Organization as Design

Another research method that may be effectively employed at the design-scienceinterfaceis simulation simulationmethods involving modeling. In particular, simulationand both conceptualmodels (mathematical to be very promisinglearning laboratories)appear such a methodis, for example, system dynamicsmod2001, Maaniand Cavana2000, Oliva eling (Akkermans and Sterman modeling 2001). In this respect,simulation allows people to build and test models describingthe currentand desired (states of the) system, which helps of them to move outsidethe mentalboundaries the current situation. In general,the collaboration betweeninsidersandoutsiders with regardto the organizational systems under study appearsto increasethe effectivenessof research projects at the design-scienceinterface.Bartunekand Louis (1996) have developed guidelines for building insider-outsiderconfigurationsin organizational research. With a few exceptions,design inquiryis left to practitionerssuch as organization developmentprofessionals and managementconsultants,with the result that the body of design knowledge is rather fragmented and dispersedover many different sites. Because the design mode of engaging with organizational phenomena has moved away from the academic community to other sites in the economy and society, a persistent gap betweenorganization theoryandpracticeexists. research must therefore be redirectedtoward Design more rigorousresearchto producedesign propositions that can be groundedin empiricalresearchas well as tested, learned,and appliedby "reflective practitioners" (Schin 1987) in organizationand management.The form of such propositionsand rules-as the core of design knowledge-is very similarto knowledgeclaims in science. This similarityis an important conditionfor and collaboration between design and science, dialogue can to the extentthatthese propositions providea shared focal point.A morerigorousapproach design inquiry to will facilitatecollaboration dialoguewith organizaand tion science. In this respect,recent studies of design as an empirical object have adopted co-evolutionaryperspectives on organizational systems (e.g., Galunicand Eisenhardt Lewin and Volberda1999, Victor et al. 2000, 2001, Wageman2001) that are congruentwith the ideas put forward here. For example, Wageman (2001) examines the relativeeffects of design choices and hands-on coaching on the effectivenessof self-managingteams. Wageman's findings show that only design activity and that affectsteamtaskperformance, in addition, welldesigned teams are helped more than poorly designed

ORGANIZATION 14, SCIENCE/Vol. No. 5, September-October 2003

teamsby hands-on 2001). Although coaching(Wageman are and Wageman's propositions descriptive explanatory in nature, canbe rewritten a set of (preliminary) into they design propositions concerningthe design and coaching of teams-as objects with descriptiveas well as imperative properties. In general, the synergy between science and design can be summarizedas follows. First, the body of knowledge and researchmethods of organizationscience can serve to groundpreliminarydesign propositions in empiricalfindings,suggest ill-definedareas to and which the design mode can effectively contribute, build a cumulativebody of knowledgeaboutorganization theoryandpractice.In turn,the design mode serves to translateempiricalfindingsinto design propositions for furtherpragmaticdevelopmentand testing; it can suggest research areas (e.g., with emerging design in thatneed empiricalgrounding organizapropositions tion science)to which science can effectivelycontribute; and, finally, design researchcan reduce the relevance gap betweenscience and the world of practice.

After enjoyinga certaindegree of paradigmatic consistency andunityin the firsthalf of the 20th century, organizationalresearchhas become increasinglypluralistic in nature(Pfeffer 1993, Weiss 2000). In the years since Burrell and Morgan's(1979) presentationof multiple the approaches, attentionof the communityof organization scholarshas been turningaway from the important issue of researchobjectivesand our commitments as researchers. In this respect, science and the humanitieshelp to understand existing organizational systems, ratherthan to actuallycreatenew organizational artifacts. This suggests that organizationstudies must be reconfigured as an academic enterprisethat is explicitly based on science, humanities,and design. With a few exceptions in the academiccommunity,design inquiry into and organizingis currentlylargely left to organization such as organization practitioners developmentprofessionals and managementconsultants.As a result, the body of design knowledge appearsto be fragmented and dispersed,in any case more so than science- and humanities-based knowledge of organization.Design be towardmorerigresearchshouldtherefore redirected orous research,to produceoutcomesthat are characterized by high externalvaliditybut thatare also teachable, Collaboration learnable,and actionableby practitioners. and exchangebetween science and design can only be is effective if a commonframework availablethatfacilbetween the two. and communication itates interaction

569

Concluding Remarks

A. GEORGES L. ROMME

Organization as Design

The argumentin this paperinvolved a modest attempt to definethe main conditions,differences,and synergies research of three modes of engaging in organizational the Table 1). Subsequently, natureand contribution (see in of the design mode was exploredandillustrated more for detail. Finally,a framework exploitingthe potential science and design was synergiesbetween organization Table2). proposed(see This paper has focused on the interface between design and science, which points to the fact that the design-humanitiesinterface is a promising area for futurework.For example,the role of valuesin design-such as in the areaof participation-was discussed,but needs to be studied more extensively: Do these key values actually affect the design process, and if so, with standards how? Is it possible to define measurable of regardto the implementation these values? Another example is the aesthetic dimension of design. Challenging the familiarimages of scientific management, Guill6n (1997) shows that this early design approach had and still has a strong aestheticinfluenceon architecture and the building industry.This suggests that researchers operatingin the areaof design organization should acknowledgeand study the often implicit aesof thetic aspectsandimplications theirwork.In general, deliberateethical and aestheticchoices, design requires with respect to the broaderpurposes and particularly the systems that help to understand existing ideal-target situationandto motivatethe designprocess.Criticaland theorizingmay thereforeserve to study the postmodern role of these ethical and aestheticelements of design, for example, to explore to what extent new organizain are tionalartifacts liberating natureandto whatextent and areaffectedby ideologicalmanipulation control they Parker1995, Vince 2001). (cf. patterns Complexitytheory,the studyof macroscopic in collections of interactingelements, has been reditowardnotions of emergence,corecting the literature evolution, and complex adaptivesystems (e.g., Lewin and Volberda1999, McKelvey 1997). Evidently,design proprojectsare embeddedin a networkof interacting cesses, agents, and systems. However,there is hardly the any researchthat approaches notion of design from the perspectiveof complexitytheory.3The application of complexitytheoryto the co-evolutionof design processes and objects is therefore a promising area for futurework. The need to broaden organizationstudies toward design has majorimplicationsfor the doctoral,master, whichorganization andundergraduate through programs scholarsand professionalsin spe are trainedand socialthe ized. Currently, only optionavailablefor newcomers

570

in the field of organization studiesis to choose between a loyal memberof either "mainstream" scibecoming The ence or the humanities subculture. science approach to a large extent continues to prevail in organization studies, in part because most Ph.D. trainingprograms tend to focus on it. In addition, the liberal arts tralevel in the United States dition at the undergraduate and elsewhereis entirelybased on science and humanities subjects.As a result,design tends to be perceived and positionedas an applied discipline, with a minor with the "big three" role (if any) in educationcompared disciplines: naturalsciences, social sciences, and the humanities(Bloom 1987, Ziman 2000). If organization scholarswouldlike theirdisciplineto play a constructive role in society,the trainingand socializationof students andjuniorscholarsis the firstplace to start. In this respect,the humanrace has been profoundly of changing the parameters the evolutionaryprocess, between the as particularly a resultof the collaboration naturalsciences and the design and engineeringdisciplines. Our capacity for learning,producingknowlcomplexsystemshas edge, anddesigningandorganizing often unintended, an extraordinary, impacton although societal evolution.The key questionfor scholarsin our is: field therefore For whatpurposesare we going to use our scholarlycapacityfor learningand creating?Drawthis ing on designresearch, capacitycan be used to guide humanbeings in the processof shapingand developing towardmore humane,participative, their organizations futures.This is a complex and challengand productive ing task that requiresintensive collaborationbetween science and design. Here we can make a organization difference. Acknowledgments

An earlier draft of this paper was presented at the workshop "A New Agenda for OrganizationTheory in the 21st Century"(EuropeanInstitute for Advanced Studies in Management) in Brussels, February7-8, 2002, organizedby HamidBouchikhi,Anne Huff, and Marc de Rond. The authoris gratefulto the workshoporganizersand participantsfor helpful comments. Useful feedback and suggestions by GerardEndenburg,Frank Heller, RobertMacIntosh,David Tranfield,Editor KimberlyElsbach, and three reviewers are also gratefully acknowledged.

Endnotes

'Moreover,Nowotnyet al. (2001) arguethat too much focus on its

epistemological core is likely to constrain the potential of science and "could be taken to imply that ultimate and absolute truth is still attain-

avoid the position able"(Nowotny2001, p. 200). I also deliberately of "paradigm 1998,Donaldson incommensurability" Czarniawska (cf.

1998). In this respect, the thesis of "paradigm incommensurability" appears to stem from a misreading of Thomas Kuhn's (1962) famous The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (e.g., Hacking 1986, Wilber

1998).

2003 ORGANIZATION SCIENCE/Vol. No. 5, September-October 14,

A. GEORGES L. ROMME

Organization as Design Checkland, P. 1981. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. Wiley,

refersto a preliminary 2In this paper,the term "designproposition" "rule,"whereas "design rule" refers to design propositions design that have been successfullytested in practice(i.e., by way of pragin as maticexperimentation) well as thosethataregrounded empirical evidence. 3An exception is the conditionedemergenceframework developed and implies organiby MacIntosh MacLean(1999). This framework can zationaltransformation be viewed as an emergentprocess that can be accessedand influencedthroughthreeinteracting gatewaysand order generating"design"rules, far-from-equilibrium, positive feedback.

New York.

, J. Scholes. 1990. Soft Systems Methodology. Wiley, New York. Cross, N., ed. 1984. Developments in Design Methodology. Wiley,

New York. B. Czarniawska, 1998. Who is afraidof incommensurability? Organ. 5 273-275. interactionism. Morgan, ed. G. Denzin, N. K. 1983. Interpretive

Beyond Method: Strategies for Social Research. Sage, Beverly

Hills, CA, 129-146.

Donaldson, L. 1985. In Defense of Organization Theory: A Reply to

References

Akkermans,H. 2001. Renga: A systems approachto facilitating networkdevelopment.System Dynam. Rev. interorganizational 17 179-193. Archer, L. B. 1984. Whatever became of design methodology.

N. Cross, ed. Developments in Design Methodology. Wiley, New York, 347-350. Argyris, C. 1993. Knowledge for Action: A Guide to Overcoming Barriers to Organizational Change. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco,

U.K. the Critics.Cambridge UniversityPress,Cambridge,

1996. For Positivist Organization Theory: Proving the Hard

Core. Sage, London,U.K. in . 1998. The myth of paradigm incommensurability management studies:Comments an integrationist. Organ.5 267-272. by

Drucker, P. E 1954. The Practice of Management. Harper and Row,

New York. Eden, C., C. Huxham.1996. Action researchfor the study of orgaW. nizations.S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, R. Nord,eds. Handbook of

Organization Studies. Sage, London, U.K., 526-542.

~,

-, -

CA. R. S. Kaplan.1994. Implementing new knowledge:The case of activity-based Horizons8(3) 83-105. costing.Accounting

D. A. Sch6n. 1978. Organizational Learning. Addison-Wesley,

K. Eisenhardt, M. 1989. Buildingtheoriesfrom case studyresearch.

Acad. Management Rev. 14 532-550.

-,

Reading,PA.

, R. Putnam, D. McLain Smith. 1985. Action Science: Concepts, Methods, and Skills for Research and Intervention. Jossey-Bass,

C. B. Schoonhoven.1996. Resource-based view of strategic allianceformation: and Strategic social effects in entrepreneurial

firms. Organ. Sci. 7 136-150.

CA. San Francisco,

Baldwin, C. Y., K. B. Clark. 2000. Design Rules, Vol. 1: The Power

MIT Press,Cambridge, MA. of Modularity.

Banathy, B. H. 1996. Designing Social Systems in a Changing World.

U.K. Plenum,New York/London, -. 1999. Systems thinkingin highereducation:Learningcomes

to focus. Systems Res. Behavioral Sci. 16 133-145.

on Elsbach,K. D., R. I. Sutton,D. A. Whetten.1999. Perspectives developingmanagement theory,circa 1999: Moving from shrill monologuesto (relatively)tame dialogues.Acad. Management Rev.24 627-633. a Emery,F. E., E. L. Trist. 1972. Towards Social Ecology.Penguin, U.K. Harmondsworth,

Endenburg, G. 1998. Sociocracy as Social Design. Eburon, Delft, The

Barley,S. R., G. Kunda.1992. Design and devotion:Surgesof rational and normative discourse. ideologiesof controlin managerial

Admin. Sci. Quart. 37 363-399. Bartunek, J. M., M. R. Louis. 1996. Insider/Outsider Team Research.

Oaks,CA. Sage, Thousand J. M., H. M. Trice. 1982. The utilizationprocess:A concepBeyer, and tual framework synthesisof empiricalfindings.Admin.Sci. Quart.27 591-622.

Bloom, A. 1987. The Closing of the American Mind. Simon &

Netherlands. to Fabian,F H. 2000. Keepingthe tension:Pressures keep the conRev. troversyin the management discipline.Acad. Management 25 350-371. and 2001. Architectural innovation Galunic,D. C., K. M. Eisenhardt. modular forms.Acad. Management 44 1229-1249. J. corporate Gergen, K. 1992. Organizationtheory in the post-modernera.

M. Reed, M. Hughes, eds. Rethinking Organization. Sage,

London,U.K., 207-226. P. Gibbons,M., C. Limoges, H. Nowotny,S. Schwartzman, Scott,

M. Trow. 1994. The New Production of Knowledge. Sage,

Schuster,New York. Boland, R. J. 1978. The process and product of system design.

Management Sci. 24 887-898.

London,U.K. relevance:A responseto Starkeyand Grey, C. 2001. Re-imagining

Madan. British J. Management 12 27-32.

of of -. 1989.The experience systemdesign:A hermeneutic organizational action. Scandinavian J. Management 5 87-104. Bunge, M. 1967. Scientific Research II: The Search for Truth.

lost ArchitecGuill6n,M. F. 1997. Scientificmanagement's aesthetic: and ture, organization, the taylorizedbeauty of the mechanical.

Admin. Sci. Quart. 42 682-715.

Berlin,Germany. Springer,

1979. Causality and Modern Science, 3rd rev. ed. Dover

New York. Publications,

Burrell, G., G. Morgan. 1979. Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis. Heinemann, London, U.K.

Rev.Books Hacking,I. 1986. Science turnedupsidedown.New York 33(3). D. Acad. Hambrick, C. 1994.Whatif the academyactuallymattered?

Management Rev. 19 11-16.

ORGANIZATION 14, SCIENCE/Vol1. No. 5, September-October 2003

571

A. GEORGES L. ROMME

Organization as Design Mohr, L. B. 1982. Explaining Organizational Behavior: The Limits and Possibilities of Theory and Research. Jossey-Bass, San Fran-

research. Hatchuel,A. 2001. The two pillars of new management

British J. Management 12 33-39.

Heller, F. 2001. On the integrationof the social sciences. Human

Relations 54 49-56.

Heron,J., P. Reason. 1997. A participatory Qualiinquiryparadigm.

tative Inquiry 3 274-294.

cisco, CA. Prima,Rocklin, Nadler,G., S. Hibino. 1990. Breakthrough Thinking. CA. Newell, A., H. Simon. 1972. HumanProblemSolving.PrenticeHall, EnglewoodCliffs, NJ. Science: Nowotny, H., P. Scott, M. Gibbons. 2001. Re-Thinking

Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainty. Polity,

Hodgkinson,G. P., P. Herriot,N. Anderson.2001. Re-aligningthe stakeholders management in research:Lessons from industrial, work and organizational psychology. British J. Management 12 41-48. Huff, A. S. 2000. Changesin organizational knowledgeproduction.

Acad. Management Rev. 25 288-293.

-,

J. O. Huff. 2001. Re-focusing the business school agenda.

British J. Management 12 49-54.

U.K. Cambridge, laws in manageNumagami,T. 1998. The infeasibilityof invariant ment studies:A reflectivedialoguein defense of case studies.

Organ. Sci. 9 2-15.

a Jackson,M. C., P. Keys. 1984. Towards systemof systemsmethodologies. J. Oper Res. Soc. 35 473-486. Jaques, E. 1962. Measurement of Responsibility. Tavistock Publica-

Oliva, R., J. D. Sterman.2001. Cuttingcornersand workingovertime: Qualityerosion in the service industry. Sci. Management 47 894-914. and M. Parker, 1995. Critiquein the name of what?Postmodernism to criticalapproaches organization. Organ.Stud.16 553-564. science: Pfeffer,J. 1993. Barriersto the advanceof organizational Acad. Managevariable. as Paradigm development a dependent

ment Rev. 18 599-620.

tions, London,U.K. Klir, G. 1981. Systems methodology: From youthful to useful.

G. Lasker, ed. Applied Systems and Cybernetics. Pergamon,

New York,931-938. towardsuccess:Preludeto a theoryof Knorr,K. D. 1979. Tinkering scientificpractice.TheorySoc. 8 347-376.

Knorr-Cetina, K. D. 1981. The Manufacture of Knowledge: An Essay on the Constructivist and Contextual Nature of Science.

Priem, R. L., J. Rosenstein.2000. Is organization theory obvious A to practitioners? test of one establishedtheory. Organ. Sci. 11 509-524. and Romme, A. G. L. 1995. Non-participation system dynamics.

System Dynam. Rev. 11 311-319.

Oxford,U.K. Pergamon, resources affectstrateM. Kraatz, S., E. J. Zajac.2001. Organizational in environments: Theory gic change and performance turbulent and evidence.Organ.Sci. 12 632-657.

Kuhn, T. 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 2nd ed.

_. _.

and 1997. Organizational learning,circularity, doublelinking.

Management Learning 28 149-160.

Universityof ChicagoPress,Chicago,IL.

Latour, B., S. Woolgar. 1979. Laboratory Life: The Social Construction of Scientific Facts. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA.

and 1999. Domination, self-determination, circularorganizing.

Organ. Stud. 20 801-832.

education drawing organization on studies. _. 2003. Organizing by

Organ. Stud. 24 697-720.

on Lewin, A. Y., H. W. Volberda.1999. Prolegomena coevolution: A framework researchon strategyand new organizational for forms. Organ.Sci. 10 519-534. of Long,J., J. Dowell. 1989.Conceptions the disciplineof HCI:Craft, applied science, and engineering.A. Sutcliffe, L. Macaulay,

eds. People and Computers V. Cambridge University Press,

-,

en J. M. Reijmer. 1997. Kringorganiseren het dilemma voor tussencentralesturingen zelforganisatie. M&O,Tijdschrift

Management en Organisatie 51(6) 43-59.

Rudolph,J. W., N. P. Repenning.2002. Disasterdynamics:Undercollapse.Admin. standingthe role of quantityin organizational

Sci. Quart. 47 1-30.

U.K., 9-32. Cambridge,

Maani, K. E., R. Y. Cavana. 2000. Systems Thinking and Modelling: Understanding Change and Complexity. Prentice Hall, Auckland.

M., Sarbaugh-Thompson, M. S. Feldman.1998. Electronicmail and communication: Does saying "hi"really matter? organizational

Organ. Sci. 9 685-698. Sch6n, D. A. 1987. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Towards a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions.

A emergence: dissiMacintosh,R., D. MacLean.1999. Conditioned to StrategicManagepative structures approach transformation. mentJ. 20 297-316. Markus,M. L., D. Robey. 1988. Information technologyand organiin zationalchange:Causalstructure theoryand research.Management Sci. 34 583-598.

CA. Jossey-Bass,San Francisco,

Schwarz, R. M. 1994. The Skilled Facilitator: Practical Wisdom for Developing Effective Groups. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco,

science. Organ.Sci. McKelvey,B. 1997. Quasi-natural organization 8 352-380. of Merton,R. K. 1973. TheSociologyof Science.University Chicago Press,Chicago,IL. in Miner,J. B. 1997. Participating profound change.Acad. Management J. 40 1420-1428.

CA.

Simon, H. A. 1996. The Sciences of the Artificial, 3rd ed. MIT Press,

MA. Cambridge, K., P. Madan.2001. Bridgingthe relevancegap: Aligning Starkey, in research.British J. stakeholders the future of management

Management 12 3-26.

572

ORGANIZATION 14, SCIENCE/Vol1. No. 5, September-October 2003

as A. GEORGESL. ROMME Organization Design Management. Harper, Taylor, W. 1911. ThePrinciplesof Scientific E New York. and D., Tranfield, K. Starkey.1998. The nature,social organization research:Towardspolicy. BritishJ. promotionof management 9 Management 341-353. S. Wilson, S. Smith, M. Foster. 1998. Teamworked I. Parry, -, organisational Gettingthe most out of teamworking. engineering: Decision 36 378-384. Management S. Smith, M. Foster,S. Wilson, I. Parry.2000. Strategiesfor -, managingthe teamworking agenda:Developinga methodology for team-basedorganisation. Internat.J. ProductionEconom. 65 33-42. Tsoukas,H. 1998. The word and the world:A critiqueof represenin tationalism management research.Internat.J. Public Admin. 21 781-817. -. 2000. Falsedilemmasin organization theory:Realismor social 7 constructivism? Organization 531-535. Van Aken, J. E. 2001. Improving the relevance of management researchby developingtested and groundedtechnological rules. Workingpaper 1.19, EindhovenUniversityof Technology, Departmentof Technology Management,Eindhoven, The Netherlands. . 2004. Management researchbased on the paradigmof the design sciences:The questfor testedandgrounded technological rules.J. Management Stud.Forthcoming. VanVlissingen,R. F. 1991. A management systembasedon consent. HumanSystemsManagement 149-154. 10 Vennix, J. A. M. 1996. GroupModel Building:FacilitatingTeam U.K. LearningUsingSystemDynamics.Wiley,Chichester, 2000. The effective Victor, B., A. Boynton, T. Stephens-Jahng. Organ.Sci. 11 design of work undertotal qualitymanagement. 102-117. Human Vince,R. 2001. Powerandemotionin organizational learning. Relations54 1325-1351. team effecWageman,R. 2001. How leaders foster self-managing tiveness:Design choices versushands-oncoaching.Organ.Sci. 12 559-577. Warfield, J. 1990. A Science of General Design. Intersystems Publishers, Salinas,CA. R. Cardenas.1994. A Handbookof Interactive , Management. Iowa StateUniversityPress,Ames, IA. Weick, K. E. 2001. Gappingthe relevancebridge: Fashions meet in fundamentals management research.British J. Management 12 71-75. Weisbord,M. 1989. ProductiveWorkplaces: Organizingand ManBerrett-Koehler, aging for Dignity, Meaning, and Community. San Francisco,CA. science:How Weiss, R. M. 2000. Takingscience out of organization would postmodernism reconstruct analysisof organizations? the Organ.Sci. 11 709-731. studies and the Wicks, A. C., R. E. Freeman.1998. Organization new pragmatism: and Positivism,anti-positivism, the searchfor ethics. Organ.Sci. 9 123-140. Wilber,K. 1998. The Marriageof Sense and Soul. RandomHouse, New York. Yin, R. K. 1984. Case StudyResearch:Design and Methods.Sage, BeverlyHills, CA. studiesas a scientificandhumanistic Zald,M. N. 1993. Organization Towarda reconceptualization the foundations of of enterprise: the field. Organ.Sci. 4 513-528. Ziman, J. 2000. Real Science: What It Is, and What It Means. U.K. Press,Cambridge, Cambridge University

ORGANIZATION SCIENCE/Vol1.14, No. 5, September-October 2003

573

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)