Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

FC MGT in East Asia

Transféré par

Gown Cha LizDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

FC MGT in East Asia

Transféré par

Gown Cha LizDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Franchise Management in East Asia Author(s): Peng S. Chan and Robert T. Justis Source: The Executive, Vol. 4, No.

2 (May, 1990), pp. 75-85 Published by: Academy of Management Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4164949 . Accessed: 23/08/2011 01:15

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Academy of Management is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Executive.

http://www.jstor.org

? Academy of Management Executive, 1990Vol. 4 No. 2

.............................................................................................................................................................................

Franchise East Asia

management in

Peng S. Chan, California State University, Fullerton RobertT. Justis,Louisiana State University Executive Overview

Franchising is the fastest growing method of doing business today. It is becoming a major catalyst for economic growth, employment, and development not only in the United States but also in the international marketplace. Franchising has moved from traditional product (trademark) areas such as automobiles, petroleum, and soft-drink bottlers to the standard industries of fast food, cosmetics, cleaning, convenience stores, computers, and financial services. In almost any area of business, franchising is a reality. We believe that it will surpass every method of doing business by the end of this century. The move toward international franchising is increasing as the U.S. domestic market becomes saturated and opportunities in foreign markets become apparent. We found that the economic growth of the Asian Pacific Rim in the last decade is presenting tremendous opportunities for U.S. franchisors. Several strategies for franchising in East Asia are presented in this article. Major considerations involved in franchising in this region-understanding the local culture and foreign regulation-are also discussed. Finally, the climate for franchising in Japan, the People's Republic of China, and other major East Asian countries are examined.

.............................................................................................................................................................................

Article

It is not necessarily news that a third of American retail dollars are spent through franchising stores. It is not unusual for a consumer to rise early in the morning to use automotive products, withdraw money from a bank, eat at a restaurant, visit a dentist or a doctor, buy drugs from a drug store, take clothes to the cleaners, visit a health club, and pick up food for the family before returning home at night-all done through franchised organizations. Franchising, which is the fastest growing method of doing business in the U.S., is changing not only our marketing system but also our way of life. It offers opportunities for entrepreneurs and ordinary people to own a business as well as to compete favorably with larger establishments. Although born in the U.S.A., franchising has spread abroad in recent years and is gaining widespread acceptance in international markets. Today there are over 350 franchising companies in the United States with more than 31,000 outlets operating in international markets including Canada, Australia, United Kingdom, Japan, and the rest of the world. 1 One of the areas in which it is growing rapidly is in East Asia. This growth has corresponded somewhat to the overall economic expansion of the Pacific Rim countries in the last decade.2 Japan, for example, has emerged as one of the largest franchising countries in the world and is runner-up only to the United States and Canada with respect to the total number of franchisors and franchisees established. The purpose of this article is to exalmine some strategies for franchising in East Asia and to survey the business and regulatory climate in this region, Japan alnd

75

Academy of Management Executive

China, in particular. After briefly defining what franchising consists of we examine strategies for franchising in East Asia. Next, the cultural aspects of managing franchising organizations in East Asia are discussed. We conclude with an assessment of the economic and regulatory climate in Japan and China, and several other major East Asian countries.

The Franchising Boom

According to a recent survey by the Department of Commerce, Japan continues to be the second largest market for United States' franchisors with a total of 7,366 units, of which 72 percent represent various food categories such as restaurants, ice cream stores, convenience food stores, and donut shops. China now accepts foreign franchisors into its country and has established a working relationship with some franchising organizations as it builds up hotels and food service businesses.

The franchisee has an opportunity to use proven methods of operation, large-scale, high-impact advertising, recognized brands or trademarks, and

continuing

The proliferation of franchising in foreign countries is due to several economic and demographic trends: (1) universal cultural trends, (2) increased disposable income, (3) improved international transportation and communication, (4) improving educational levels, (5) rising standards of living, (6) increasing number of women in the workforce, (7) smaller families with two or more incomes, (8) shorter work weeks, (9) younger generations willing to try out new products, and (10) demographic concentrations of people in urban areas. In addition, franchisees in foreign markets are realizing the same advantages that have attracted so many U.S. entrepreneurs to the idea. The franchisee has an opportunity to use proven methods of operation, large-scale, high-impact advertising, recognized brands or trademarks, and continuing management and technical assistance. Hence, franchising provides an opportunity for the franchisee to succeed as a small business owner because of the knowledge, methods, competitive experience, and advertising clout of the franchisor. Both the franchisor and franchisee bring their strengths to the business arrangement.

management and technical assistance.

There are five major starting strategies for franchising in East Asia: (1) the establishment of a master franchisee, (2)joint venture (doing business with foreign companies or individuals), (3) licensing, (4) direct investment, and (5) establishing a franchising agreement with the local government as franchisee.

Master Franchisee. The master franchisee may be an individual, business, or conglomerate corporation which assumes the rights and obligations to establish franchises throughout a particular country or region (see Figure 1). This is a very common strategy used by American firms to franchise into Asian countries. McDonald's and Kentucky Fried Chicken have successfully used this strategy in

Master Frmrchtsee

SLbfrcncisees Subfrmnchisees Stbfracfisees

Figure 1. Master Franchisee Organization

76

Chan and Justis

Asian markets. Normally, the franchisee sets up 1 or 2 stores during the first year of operation and expands to 25 or 30 stores within 5 to 10 years. Master franchisees have the option of developing sub-franchisees or opening all units by themselves. The master franchisee in the host country assumes the role and responsibilities of the franchisor. All royalty fees are paid by each sub-franchisee directly to the master franchisee; the master franchisee usually keeps up to 60 percent of these royalty payments and then submits the remaining 40 percent to the headquarters operation. Generally, all advertising fees are paid directly to the master franchisee, who then uses them for local (host nation) advertising.

Furthermore, the local

partner can handle all

language problems, cultural differences, and help develop local markets through appropriate means of advertising and promotion.

The International Franchise Association reported: "Master franchising is the method used by 57 percent of responding members franchising Individual contracts (licenses) are used by 19 percent of internationally.... respondents to the new survey, joint ventures by 12 percent, and foreign subsidiaries (direct investment) by 6 percent."3 Joint Venturing. With this strategy, the franchisor teams up with local citizens in establishing franchise units. Master franchising is actually a special form of joint venture, where the franchisee is given the right to sub-franchise or establish franchise units within a particular country or region. In a pure joint venture, the franchisee does not possess this right. There may be as many joint ventures as the franchisor may wish to enter within a particular country or region, whereas there can only be one master franchisee in a particular country or region. Both the master franchising and joint venture strategies share certain advantages. For example, they require investment from both the franchisor and the franchisee in the foreign business operations. This is an advantage because many countries require local equity injection as a requirement for obtaining government permission and also because other methods of franchising may not be allowed in the country. The local partner in a joint venture is seen as a "joint partner" rather than a franchisee. The Hilton Hotel system uses joint venture management contracts to manage its hotels throughout East Asia. Another advantage of master franchising and joint venturing is that the local partner understands the political and bureaucratic problems of his country far better than his foreign partner and is in a better position to negotiate with government agencies and private businesses. Furthermore, the local partner can handle all language problems, cultural differences, and help develop local markets through appropriate means of advertising and promotion. Both the master franchising and joint venture strategies provide native individuals or organizations the opportunity to develop and manage franchising systems. Many East Asian countries have regulations limiting expatriate visas. This means that the franchisor either has to manage an indigenous staff from thousands of miles away or rely on a joint venture partner. The government may also limit royalties and the transfer of funds. The master franchise or joint venture has the advantage of spreading the risk of investment and providing opportunities for local involvement and participation. Critical elements to remember in establishing a joint venture agreement with an East Asian investor are royalties, fees, capitalization, personnel, quality control, accounting, access to records, term, termination, and rights on termination. The right to retain the trademark may be limited to a five year contract by government agencies. In addition, the success or failure of joint ventures usually depends on selecting the right partner. Licensing. Another method of international franchising is for the franchisor (licensor) to develop an agreement with a local licensee (franchisee) and offer the right to use a product, good, service, trademark, trade secret, patent, or other valuable items in return for a royalty fee. The franchisee usually benefits from the 77

Academy of Management Executive

technical or business knowledge of the franchisor. In return, the franchisor is given the opportunity to enter a foreign market at little or no risk. Coca-Cola has entered most of its East Asian markets by licensing bottlers (technically, franchising bottlers) throughout East Asia and providing the syrup to produce the soft drink. Direct Investment. A fourth strategy for entering East Asian markets is through direct investment. The franchisor simply invests in company-owned stores or subsidiaries in foreign markets. This strategy is the direct opposite of the master franchisee, joint venture, or licensing agreement where the local franchisee controls the business. It is seldom used in East Asian countries because local governments generally do not allow foreign investors to own and control the entire business. Creating a company-owned store or wholly-owned subsidiary in a foreign country means that the foreign investor (franchisor) provides all the money necessary for starting up the local unit. The foreign investor is also responsible for the management and operation of that unit. This mode of franchising is opposed by many governments because there is a lack of local investment and management development involved. Since indigenous people do not have any equity in this mode of franchising and do not own the unit they can only be employees. The major problem with this strategy is the foreign investor's lack of familiarity with local conditions, which exposes the franchising organization to many business and political risks. This has caused the demise of direct investment franchises in many foreign countries. Government. The final strategy for franchising involves the foreign government as the local/master franchisee. This strategy is actually a variation of the master franchising and joint venture strategies in that the local partner is the government instead of a private individual or business. The foreign government can be a master franchisee or merely a joint venture partner, depending on the particular arrangement. This strategy is used primarily by foreign firms franchising into China. Kentucky Fried Chicken, for example, used this strategy when it entered the Chinese market recently. The company's operation in China is a joint venture with KFC International which contributes 60 percent of the investment, the remaining being shared between 2 Chinese government bodies. The Sheraton Great Wall Hotel in Beijing, China, is a joint venture with Sheraton Corporation as the franchisor and the Chinese government as the franchisee. The Chinese government appoints the managers and administrators needed to run the hotel. These people are then trained by the Sheraton staff.

2 Franchisor

~~~~~~~~~~Business

Foreign

Agreement

Goverrnment Partner

Control

Figure 2. Government-ControlledFranchise Organization|

78

Chan and Justis

There are several advantages in having the government as the local franchisee. First, the franchisor need not worry about compliance or non-compliance with the law. Second, financially the government is in a stronger position than a business or an individual and would have little difficulty providing the necessary capital to run the franchise. Third, general adherence to quality standards is more likely. Finally, payment of royalty fees is guaranteed unless otherwise stated in the franchise agreement. A disadvantage of this mode of franchising is that the government is generally less able to attract qualified managers and staff than a private business. Furthermore, as in the case of most bureaucracies, government workers suffer from a lack of motivation due to weak incentives. Loss of control is somewhat inevitable because governmental operations are so large. In addition, the restrictions imposed by the government on the franchisor may limit options and activities. For example, the government may require that the local unit be restricted to a certain area which may turn out to be a poor location.

Cultural Considerations

Managing franchising organizations in the international arena is similar to managing any other form of business in a foreign country: success depends in large part upon how well the franchisor understands the foreign market. And this requires, among other things, a good understanding of the society and culture. Den Fujita, the president of McDonald's Company in Japan notes, "American exporters should study the cultural aspects of Japan more carefully. You must send first-class Americans, experts, to Japan. Before you start production, you must learn Japanese culture and what Japanese are like. Then you can export in huge quantities."4 Indeed, McDonald's success abroad is due to its ability to introduce major cultural change. In Japan and other East Asian countries, McDonald's not only had to introduce the hamburger but also influence the local management culture. The company established a Hamburger University in Japan to train store managers how to run an American business Japanese-style. In a major departure from typical U.S. practice, the company in Japan avoided the suburban sites and instead focused on urban shopping centers where the customers tend to be. The company also made modifications, such as targeting all advertising to younger people, because the eating habits of older Japanese are very difficult to change. The company even went to the extent of changing the pronunciation of their name to "Makudonaldo" because the Japanese found it difficult to pronounce McDonald's. For the same reason, Donald McDonald replaced Ronald McDonald in Japan.5

Indeed, McDonald's success abroad is due to its ability to introduce major cultural change.

Translation and not pronunciation was a problem for Coca-Cola in China. When the world's largest soft-drink retailer entered the Chinese market in 1982, it needed to translate its trademark into the Chinese language. One of its first translations meant "bite the wax tadpole." After much professional consultation, the Chinese characters which the company now uses translate as "permit the mouth to rejoice."

Cultural Traits

Since an indepth study of Asian cultures is beyond the scope of this report, we focus on China and Japan-the two most important countries in terms of population and size of economy. Cultural traits that we think are useful in the management context are highlighted. There are many similarities in the cultures of the East Asian people. The cultures of the East Asian countries are deeply rooted in the teachings of the Chinese philosopher, Confucius. Futurologist Herman Kahn labels these cultures as "neo-Confucian." He suggests that Confucianism is to East Asia what the 79

Academy of Management Executive

Protestant ethic is to Western Europe. Kahn asserts that the East Asian countries have common cultural roots going far back into history, and that for the post 30 years this cultural heritage has given them a competitive advantage for success in business. 6 Confucianism consists of practical rules to guide daily life such as: (1) respect for the elders and tradition; (2) importance of acquiring education and skills; (3) importance of hard work, persistence, and patience; (4) importance of self-respect and dignity ("saving face") in the conduct of social relations; (5) thrift, and (6) the family's position as the threshold of all social organizations. The last teaching, in particular, has molded Asian society into its present form. A lot of Asian (especially Chinese) businesses are run by the family, which includes not only the immediate family, but all other blood ties as well. The Chinese and the Japanese do differ in this respect, however. Some evidence shows that the Chinese are more concerned for their family than the organization they work for. While it may be difficult for the Chinese to transfer their loyalty from the family to the workplace, the Japanese have little difficulty in doing that.7

.............................................................................................................................................................................

In dealing with the Chinese or Japanese, negotiations may take a long time, as many as three years for a licensing agreement. This problem is exacerbated in China because of the involvement of multiple parties. The Chinese and Japanese are tough negotiators, and they believe that patience is of particular value in negotiations.

In addition, it is advisable to go through a middleman or third party when negotiating. Promotion of one's products or services is usually more effectively done through a third party or documented literature. Choosing a good partner may be just as important as patience.8 In the classic film, "The Colonel Comes to Japan," shown by Kentucky Fried Chicken, Mitsubishi (the company's Japanese partner) kept iterating its position that a good partner is a patient partner. McDonald's partner in Japan was the most critical element to its success there. Normal cut-and-dry business relationships 'a'la American are insufficient to satisfy the Chinese or Japanese; these must be suplemented by a social relationship. In fact, it is often during the "entertaining phase" that business and political matters are completed. Both cultures place a lot of emphasis upon trust and mutual connections in business. The Chinese and Japanese come from "non-adversarial" cultures where problems are traditionally solved through mediation and compromise. They favor non-legalistic practices instead of more formal and legal ones. Insistence on highly legalistic documents may be viewed as mistrust. Preserving dignity and achieving accord and harmony are usually more important than achieving higher sales and profits. The Chinese and Japanese are more interested in long-range than short-range benefits. There is also emphasis on reciprocity in social and business relationships-in spirit, at least, if not in gifts.9 Franchising seems to fit well with the existing structure of most Asian businesses-it is an ideal form of a family-run business. Most franchise organizations in the United States originated as the "mom and pop" type and many remain family-run businesses today. In fact, McDonald's often brags about its ability to preserve a "family-like culture" when talking about its successes abroad. 80

Chan and Justis

Other long-standing Asian traditions, such as the master-apprentice relationship, are compatible with the franchisor-franchisee relationship, as opposed to the more distant seller/buyer relationship. The inherent inequality in the franchisor-franchisee relationship actually represents a very desirable state in Asian cultures. Asian qualities such as the work ethic, loyalty to the organization, and attraction to the West and Western products/services, also suggest that the franchising concept would work in these cultures. One negative aspect of franchising may be the termination clause which runs counter to the Japanese ideal of a lifetime career. This ideal, however, is beginning to change as we see the increasing use of placement counselors and job-search agencies in Japan.

Foreign Regulation

Although plentiful opportunities exist for franchising in East Asia, laws and regulatons imposed by local governments create problems. Today local governments throughout the region discriminate against franchising. It is particularly acute in developing countries where the efficient use of scarce resources and the importation of technological services and businesses are great concerns. Developing countries discriminate against franchising because it is viewed as a marketing system rather than as an economic contribution to the country. Franchising agreements that are technology-based, however, are highly favored by local governments because they provide an advanced technology or service needed by the developing country. Franchises for general industrial products are less favored. Franchises that involve mere usage of trademarks are probably the least favored among the East Asian governments. 10 Many Asian countries view franchise agreements (particularly trademarks) as instruments of exploitation. It is argued that trademarks cause prices to rise without a corresponding increase in the quality of the product/service. Persuasive advertising, as argued, will lead to resource misallocation and ultimately to an adverse balance of payments. This negative view, however, is beginning to change. Today, franchising plays a significant role in the economic development of Japan and the newly industralized countries of East Asia. It is providing business opportunities for local people and is expected to contribute to economic growth and increased employment in the East Asia region.

Climate and Prospects

Japan Japan is probably the strongest advocate of franchising in East Asia. The first U.S. franchises appeared in this country around 1965 with seven franchise establishments. This number has increased tenfold. Arby's, Budget Rent-A-Car, Dollar Rent-A-Car, Computerland, Holiday Inn, Pearle, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Dairy Queen, Denny's, International House of Pancake, Putt-Putt Golf, Century 21, Mrs. Field's, Steve's Ice Cream, and Dunkin' Donuts are just a small sample of franchises residing in Japan. McDonald's is the largest fast food business chain in Japan, with sales revenues of over $700 million a year. McDonald's, however, is facing increasing competition from both Japanese and other U.S. burger chains. In fact, despite the tripling of sales and the number of franchised units over the last decade, franchising still accounts for only 4 percent of total retail sales in Jalpan, as compared to 33 percent in the United States."l The regulaltory climate in Jaipan is conducive to franchising. Japan recently underwent mnajorchanges in foreign investment regulations. Prior to these

Academy of Management Executive

changes, notification to relevant ministries through the Bank of Japan was required to set up a wholy-owned subsidiary or joint venture operation.

.............................................................................................................................................................................

Today, Japan encourages foreign investors to develop business opportunities in Japan. Foreign franchisors can bypass a prescribed waiting period imposed by the government to develop franchising opportunities. Joint ventures are encouraged and have been the most successful type of operations in Japan.

It is now easy to remit fees or royalties back to the franchisor countries. Exchange control approval is not required. The profit tax imposed upon the joint venture or subsidiary is around 55 percent, by far the highest among all East Asian countries. Conversely, the 10 percent withholding tax imposed upon dividends and royalties payable to the U.S. franchisor is lower than that of most other East Asian countries.

China

With a population exceeding one billion, China represents a huge potential market for foreign investors. Since 1974, China has embarked on a program of economic modernization to improve its industries, defense, agriculture, and science and technology to world standards by the year 2000. In sharp contrast to Japan, franchising in China today is embryonic at best. China has only very recently opened its doors to foreign businesses. Hotel chains such as Holiday Inn and Sheraton Corporation were among the first franchises to make inroads into Chinese territory. More recently, fast-food businesses, which have already established themselves in other East Asian countries, are trying to get a slice of this huge market. Kentucky Fried Chicken established its first outlet in Beijing in 1987. It is now the world's largest KFC restaurant with unit sales of over 350,000 chickens per year. The company also plans to open more outlets in Beijing and expand into other major Chinese cities such as Canton and Shanghai. McDonald's has also indicated its plans to go into China, although its move will depend on the emergence of a Chinese middle class. The hamburger chain is already helping China improve its future foreign exchange in various ways. One of the major difficulties for franchising in this country is the plethora of laws and regulations governing foreign investment. 13 The Chinese government, through its agencies and officials, closely monitors all foreign businesses. In general, the Chinese government has a preference for foreign investment with equity being provided by both parties. Hence, joint ventures are rather common, with the Chinese government acting as the local franchisee. For joint ventures, approval is required from the foreign exchange control authority (called the State Administration for Exchange Control) for the expatriation of royalties, or fee payments. This is generally not a problem once a franchise is approved. The use of direct investment or a wholly-owned subsidiary has been effectively precluded in the past. Recent developments, however, have indicated that wholly-owned foreign operations are now encouraged. Multinationals, such as PepsiCo, have been able to establish 100-percent-owned operations in China. China has also begun to recognize the need to offer protection to foreign owners of trademarks. China imposes a 33 percent profit tax on the joint venture or subsidiary and a 10 percent withholding tax on royalties and dividends payable to the U.S. franchisor. 82

Chan and Justis

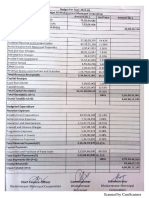

Another major stumbling block to foreign operations in China is the dearth of local management skills and knowledge. The overly centralized Chinese economic system does not foster these skills. The Chinese general manager is not required to do long-term planning, since the plan is made at the top. Since he has control over so few resources (most of which are defined and fixed in the annual plan) setting long-term goals and strategies is futile. In such an environment, management skills are not developed. In addition, the education level and technical expertise of top Chinese management are very low. Given this, it is not surprising that management usually adopts a satisfying-the-bureaucracy attitude and demonstrates a general lack of initiative. 14 In the past, the People's Republic of China has rejected Western management Table 1 Franchising in East Asia Country South Korea Regulations - Foreign investment * Exchange controls Status of Franchising

* Franchising not

Taxes

* 40%profittax on

New Developments

* In the

Singapore

* Approval required for

retailing and licensing by the Ministryof Trade and Industry

Hong Kong

* Limit on

encouraged * Jointventures possible if local franchises hold 50% * Held by large conglomerates * Foreign investors expected to pass on relevant experience, skills, & procedures to Singapore citizens.

* Generally

joint ventures withholding tax * 10.75% on royalties & dividends payable to U.S. franchisor.

* 40%profittax on

process of recognizing international trademarks, patents, tradenames & intellectual property

the foreign subsidiary of joint venture

16.5% profit tax on

*

the

freely open

Food service

Taiwan

repatriationof royalties while dividends can be paid back to franchisors. * Strictexchange control and foreign investment regulation * Foreign investment approval required for the repatriationof profitsor royalties

* Exchange

to foreign franchisors * No trade barriers * Franchising through a wholly-owned subsidiary not usually granted * joint ventures agreements * Few agreements extend beyond 5 years

* Wholly-owned

foreign subsidiary or joint venture * 1.65% withholding tax on royalties * 35%profittax on joint ventures * 35%tax on dividends * 20%tax on royalties

businesses & hotel franchisors are finding lucrative market.

* Recently opened

a Patent & Trademark consulting center

Malaysia

control

* minimal

* Recent

policies to boost

administered by the Central Bank on behalf of the Malaysian government. * Importcontrolgovernment

Thailand

* Exchange

subsidiary or joint venture

economic development have relaxed regulations

controls

* Joint ventures

* 20% Dividend

tax

* Thai-U.S.

Friendship

* Foreign investment

* Franchising with

* 25%Royalty tax

Indonesia

* Stringent foreign

investment laws Philippines

*

majorityforeign ownership- not approved. * Jointventures-only if they fall into the govt.'s prioritylist

* Jointventures

* 40%profittax

* 20-45% profittax on

Exchange controls * Foreign investment

* Agreements

limited to

5 years

a graduated scale * 20%tax on dividends & royalties * 35%profittax * 20%dividend tax * 25%royalty tax * 1-2% expatriation of royalties.

Treaty has made U.S. franchisors exempt from alien business control laws * Most franchises are rejected if theyfre not technology-related

83

Academy of Management Executive

systems for cultural, environmental, and ideological reasons. The situation has begun to change. Since 1978, several organizations have emerged that are promoting Western management education and the application of Western management techniques. Two notable organizations are the Chinese Research Association for Modern Management and the China Enterprise Management Association. More change seems to be in store. For example, in early 1988, the Chinese Parliament (the legislative arm of government) was considering passing a new enterprise law aimed at strengthening the manager's role and giving enterprises more control over assets. Under the new law, the local political party will still have a say in management, but its role will be reduced to "guaranteeing and supervising" to ensure that party policies are carried out. The intention of this law is to divorce ownership of state enterprises from their management. It will also give legal backing to the ongoing experiment of allowing individuals or groups to lease small businesses from the state. 15

Future Prospects: What Are We Waiting For?

Opportunities for franchising in East Asia are plenty. Regulations on foreign investment are being relaxed and franchising is acting as a catalyst for economic development in Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan. It is also transferring management skills and know-how to countries that needed them. Given these benefits, it is foreseeable that franchising will become increasingly accepted and encouraged in East Asia. The question then is not whether U.S. franchisors should move into East Asian markets; it is when.

.............................................................................................................................................................................

Appendix

Table 1 briefly describes the climate for franchising in some of the other East Asian countries. 16

Endnotes

l A. Kostecka, Franchising in the Economy 1986-1988 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce, January 1988),8-10. 2 For documentation on this, see, for example, "ThePacific Century,"Newsweek, February22, 1988;and L. Kraar, "Reheating Asia's Little Dragons," Fortune, May 26, 1986. 3 Franchising World, 1985, 17, 4. 4 Quoted in P. Harris and R. Moran, Managing Cultural Differences (Houston:Gulf Publishing Co., 1987),398. See, also, R. Blumm, "InOsaka, Do as the Osakans Do,"Far Eastern Economic Review, August 18, 1988,59-60.

5 For an account of McDonald's success in

There is a growing body of literature on Chinese and Japanese culture and business practices, including: Harris and Moran, Endnote 3; John Frankenstein, "Trendsin Chinese Business Practice: Changes in the Beijing Wind," California Management Review, 1986, 29, 148-160; Lucian Pye, "TheChina Trade: Making the Deal," HazvardBusiness Review, July-August 1986,74-80;Lawrence Tai, "Doing Business in the People's Republic of China:

Some Keys to Success," Management

other counries, see J. Love, McDonald's:Behind the Arches (New York:Bantam Books, 1986),and Business Week, October 13, 1986. "McWorld?," 6 Herman Kahn, WorldEconomic Development: 1979and Beyond (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1979).On how Confucianism has influenced economic success in East Asia, see G. Hofstede and M. Bond, "TheConfucius Connection: From Cultural Roots to Economic Growth,"Organizational Dynamics, Spring 1988, 16, 5-21. 7 See, for example, L. Hsu, lemoto: The Heart of Japan (Cambridge, Mass.: Schenkman Publishing Co.. 1985).

B See,

for example, P. Grub, "A Yen for Yuan:

Trading and Investing in the China Market." Business Horizons,July-August 1987, 16-24;and G. Bronson, "TheLong March,"Forbes, December 15, 1986, 182-185. 84

International Review, 1988,28, 5-9; M. Bond, The Psychology of the Chinese People (London: Oxford University Press, 1981); Saunders and J. T. Chong, "Tradewith China and Japan," Management Decision, 1986,24, 7-12;J. Abegglen and G. Stalk, Jr., KAISHA, The Japanese Corporation(New York:Basic Books, R. 1985); Pascale and A. Athos, The Art of Japanese Management (New York:Warner and Robert Christopher, The Books, 1981); Japanese Mind: The Goliath Explained (New York,Linden Press/Simon & Schuster, 1983). '? For a rather interesting discussion of discrimination against franchising in East Asia, see D. Shannon, "Franchising in East Asia," East Asian Executive Reports, December 1983, 9-22. 11An interesting case study of franchising in Japan is provided by P. Zeidman, International Franchising (Chicago: Commerce Clearing House, 1987). 12 There is a growing body of literature that

Chan and Justis

focuses on the economic development and modernization of China, including: "China Throws Open Its Seaboard," The Economist, March 12, 1988;"China's Economy,"The Economics, August 1, 1987;Joseph Battat, "China in 2010:Strategic Considerations," Business Horizons,July-August 1987,2-9;Heidi and Lawrence Wortzel, "The Vernon-Wortzel Emergence of Free MarketRetailing in the People's Republic of China: Promises and Consequences," California Management Review, 1987,29, 59-76;and Dori Yang, "The Next 'Asian Miracle' May Be Under Way-In China," Business Week, November 7, 1987, 144-145. 13 For a discussion of the general investment climate in China, see HarryHarding, "The Investment Climate in China," The Brookings Review, Spring 1987,37-42.

14 See Joseph Battat, Management in Post-Mao China: An Insider's View (Ann Arbor, Michigan: UNI Research Press, 1986);S. Andors, Workersand Workplaces in Revlutionary China (New York, N.E. Sharpe, Inc., 1977);and T. Comte, "China:An Overstated Opportunity," Management Review, January 1987, 16-17. 15See Ford Worthy, "WhyThere's Still Promise in China," Fortune, February 27, 1989, 95-101;"Tryingto Manage," The Economist, January 30, 1988, 26-27, and "No Speed Limit," The Economist, March 26, 1988, 30-31. 16 This section is compiled from numerous trade and industry sources, including: J. Douress (ed.), ExportersEncyclopedia (Baltimore, Maryland: Port City Press, 1988); Shannon, Endnote 10;and various issues of The Economist and Far Eastern Economic Review.

Aboutthe Authors

Peng S. Chan is assistant professor of strategic management in the School of Business Administration and Economics at California State University, Fullerton. He is also president of The Chan Group which specializes in international strategies, investments, joint ventures, and trading with the Pacific Rim countries. Dr. Chan received his LL.Bwith high honors from the University of Malaya, and his M.B.A. and Ph.D. in strategic management from the University of Texas at Austin. Robert T. Justis is professor of management in the College of Business Administration at Louisiana State University and director of the LSU Entrepreneurship Institute. He specializes in the development and start-up of franchising and entrepreneurial organizations. He actively trains and consults with managers in numerous organizations. Dr. Justis received his B.S. and M.B.A. from Brigham Young University, and his D.B.A. from Indiana University. He is the author of Managing Your Small Business (Prentice-Hall, Inc.). His latest book, with Richard Judd, is Franchising (Southwestern Publishing Co.).

85

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- HUD Settlement Statement - 221-1993Document4 pagesHUD Settlement Statement - 221-1993Paul GombergPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit Test 6 Market Leader Intermediate Unit 6 Test Answer Key in PDF Market Leader IntermediateDocument3 pagesUnit Test 6 Market Leader Intermediate Unit 6 Test Answer Key in PDF Market Leader IntermediateSonia Del Val CasasPas encore d'évaluation

- Partnership LiquidationDocument11 pagesPartnership LiquidationBimboy Romano100% (1)

- Decodifying The Labour Codes - 11-01-2022Document59 pagesDecodifying The Labour Codes - 11-01-2022Rizwan PathanPas encore d'évaluation

- NOTES On Power of Eminent Domain Section 9Document10 pagesNOTES On Power of Eminent Domain Section 9Ruby BucitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Use The Following Information For The Next 2 QuestionsDocument4 pagesUse The Following Information For The Next 2 QuestionsGlen JavellanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Quiz Akhir IntermicroDocument4 pagesQuiz Akhir IntermicroelgaavPas encore d'évaluation

- Reflection Paper About Global MigrationDocument5 pagesReflection Paper About Global MigrationRochelle Ann CunananPas encore d'évaluation

- Banking 18-4-2022Document17 pagesBanking 18-4-2022KAMLESH DEWANGANPas encore d'évaluation

- Banking Awareness October Set 2Document7 pagesBanking Awareness October Set 2Madhav MishraPas encore d'évaluation

- Quiz Ibm 530 (Ans 13-18) ZammilDocument5 pagesQuiz Ibm 530 (Ans 13-18) Zammilahmad zammilPas encore d'évaluation

- Financial SystemDocument13 pagesFinancial SystemIsha AggarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- Cost Classification ExerciseDocument3 pagesCost Classification ExerciseVikas MvPas encore d'évaluation

- Questions and AnswersDocument9 pagesQuestions and Answersjhela18Pas encore d'évaluation

- Working at WZR Property SDN BHD Company Profile and Information - JobStreet - Com MalaysiaDocument6 pagesWorking at WZR Property SDN BHD Company Profile and Information - JobStreet - Com MalaysiaSyakil YunusPas encore d'évaluation

- A WK5 Chp4Document69 pagesA WK5 Chp4Jocelyn LimPas encore d'évaluation

- Red Ink Flows MateriDocument15 pagesRed Ink Flows MateriVelia MonicaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2019 Edp Unit 2 PDFDocument19 pages2019 Edp Unit 2 PDFchiragPas encore d'évaluation

- Bus 5111 Discussion Assignment Unit 7Document3 pagesBus 5111 Discussion Assignment Unit 7Sheu Abdulkadir BasharuPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 1: University of Foreign Trade UniversityDocument11 pagesAssignment 1: University of Foreign Trade UniversityĐông ĐôngPas encore d'évaluation

- ERPDocument9 pagesERPWindadahri PuslitkaretPas encore d'évaluation

- Ocean ManufacturingDocument5 pagesOcean ManufacturingАриунбаясгалан НоминтуулPas encore d'évaluation

- B. Proportionate Sharing of Costs and Profit.: EngageDocument2 pagesB. Proportionate Sharing of Costs and Profit.: EngageOliver TalipPas encore d'évaluation

- Mpac522 GRP AssignmntDocument4 pagesMpac522 GRP AssignmntShadreck VanganaPas encore d'évaluation

- DISCOUNT (WWW - Freeupscmaterials.wordpress - Com)Document15 pagesDISCOUNT (WWW - Freeupscmaterials.wordpress - Com)k.palrajPas encore d'évaluation

- Budget 2019-20Document21 pagesBudget 2019-20Pranati RelePas encore d'évaluation

- EE40 Homework 1Document2 pagesEE40 Homework 1delacruzrae12Pas encore d'évaluation

- SAD 5 Feasiblity Analysis and System ProposalDocument10 pagesSAD 5 Feasiblity Analysis and System ProposalAakash1994sPas encore d'évaluation

- According To Decenzo and Robbins "HRM Is Concerned With The PeopleDocument75 pagesAccording To Decenzo and Robbins "HRM Is Concerned With The PeopleCaspian RoyPas encore d'évaluation

- MR Ryan Chen-CargillDocument10 pagesMR Ryan Chen-CargillTRC SalesPas encore d'évaluation