Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Allison Diss Writing

Transféré par

VioletalauraDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Allison Diss Writing

Transféré par

VioletalauraDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

f!'.

Pergamon

English for Specific Purposes, Vol. 17, No.2, pp. 199-217, 1998 1998 The American University. Published by Elsevier Science Ltd All rights reserved. Printed in Great Britain 0889-4906/98 $19.00+0.00

PH: 80889-4906(97)00011-2

Dissertation Writing in Action: The

Development of a Dissertation Writing

Support Program for ESL Graduate

Research Students

Desmond Allison, Linda Cooley, Jo Lewkowicz and David Nunan

Abstract-Despite an explosion in the number of students writing graduate

theses in a language other than their first, there are very few accounts, either of research into the difficulties encountered by these students, or of writing programs designed to help such students present dissertations written to an acceptable standard. This article describes and evaluates a program developed within the English Centre at the University of Hong Kong to assist students who are required to present dissertations in English. The program was based on data collected from detailed interviews with graduate supervisors and a survey of graduate students, as well as an analysis of extended pieces of graduate writing. 1997 The American University. Published by Elsevier Science Ltd

Introduction

There is a growing awareness in academic circles that graduate students whose first language is not English, but who, nonetheless, are studying in English, may not only need assistance and guidance in designing and carry ing out their research, but may also need assistance with the presentation of their research in an acceptable standard ofEnglish. The Question remains, however, as to who should provide such assistance and what form it should take. Brown (1994), for example, argues that it is the responsibility of supervisors to "deliberately manage" students' writing since, by doing so, they not only encourage completion, but also help to ensure that the writing is lucid. Such management may be sufficient for those students whose difficultiesare cognitive or organizational but not all graduate students have the language and other interpersonal skills to activate advice from their supervisors. In addition, not all supervisors have the knowledge and skills needed to identify exactly what it is that needs to be done in order to

Address correspondence to: Desmond Allison, Department of English Language and literature, National University of Singapore, 10 Kent Ridge Crescent, Singapore.

200

D. Allison et al.

Dissertation Writing in Action

201

improve the comprehensibility of a given piece of writing. The problem is compounded when the supervisors are themselves second language speak ers of the language in question. In response to apparent needs, a number of universities have developed graduate writing programs taught by applied linguists to supplement the support that the individual supervisors can give in this area. To be effective, such programs must clearly enjoy the confidence and cooperation of super visors as well as students. (See Belcher 1994 on the importance and com plexity of relations between graduate students and their advisers.) They must also be cost-effective and comply with university regulations. Hence programs offered vary considerably according to the educational context for which they are designed. This paper describes one such innovative program which was developed at the University of Hong Kong (UHK) to help ESL graduate students already working on their dissertation. The paper looks at how the program was developed, implemented and subsequently revised on the basis of feed back from students. It offers some insights into what is currently expected of graduate students writing in a second language context and some positive solutions to the problems encountered in developing such a multidisciplinary course in this context Although the situation in Hong Kong is specific in that graduate students do not follow any taught courses, the approach adopted by the course developers should be of relevance to a wider audience. Many writing problems ESL graduate students have to grapple with are similar regardless of the situation they are studying in, hence we believe the approach we detail can be applied in a variety of situations. Before addressing these issues, however, we briefly review the main approaches to graduate writing that have been described in the literature.

!~

fil';

Existing Approaches to Graduate Writing Programs

In a situation in which graduate studies involve taught courses leading to a dissertation, as is commonly the case in the United States, the writing program often reflects the type of writing tasks required in the content classes. At the University of Michigan, for example, writing courses for graduate students cover topics such as general-specific texts, problem-solu tion texts, data commentaries, summary writing, writing critiques and con structing a research paper (Swales 1995). These categories match well with those reported by Casanave and Hubbard (1992) in a survey seeking information from faculty on the type ofwriting assignments given to doctoral students in their content courses at Stanford University. The categories reported include problem solving, analytical writing, critical summaries, noncritical summaries, literature reviews, lab reports, long research papers and brief research papers. The writing programs in this context are clearly intended to assist students with the types of writing that they need to master to succeed in their content classes. In Academic Writing for Graduate Students, Swales and Feak (1994a, 1994b) cover several of the types of

writing mentioned above. The research paper in particular seems to be a focus of attention, as in Swales' earlier work with graduate students which focuses mainly on the research paper as a prestigious and valued artefact (Swales 1987, 1990). Other programs in the United States have been described in Benson and Heidish (1995), Casanave and Hubbard (1992), Frodesen (1995), Johns (1993), Richards (1988), and Silva et al. (1994). Of these, however, only Richards (1988) deals with dissertation writing itself. She describes an ESP course that she designed and ran as a departmentally required course for students of range science (the biological study of range lands). Although her course differed from the program at the UHK to be discussed below, in that ours was voluntary and cross-disciplinary, a notable similarity is her emphasis on the size and scope of the writing task. The task, as Trimble (1985) notes, is an instance of total discourse, requiring different pedagogical treatment from the production of shorter texts. The situation of graduate research students following the British system, as is the case for students in Hong Kong, differs from that of students in the United States in that Ph.D. and M.Phi!. research degrees do not include a taught course component Some students may previously have completed a taught master's degree program, but once registered for a research degree, a student works alone on a dissertation topic in consultation with a super visor. The dissertation and an associated oral examination will normally comprise the only examinable outcomes. It follows that certain forms of academic writing, such as the writing of summaries and lab reports, that may be targeted in other programs, would have no obvious relevance in a writing program in a university following this system. It is probably also desirable that writing programs in such a context be introduced fairly early in a student's studies as it is likely to be the only contact that the student will have with a teacher apart from his/her supervisor. It may, therefore, be the only opportunity that the student has to receive input on writing skills and, depending on the type of program, feedback on the writing produced. The absence of a taught course component also means that any writing program introduced has to be on a voluntary basis, although some uni versities require students to attend a presessional course which covers the whole range of study skills necessary in an academic context This may be the only course students attend during their graduate studies, but growing concern with language difficulties is leading many universities to introduce other courses. Dudley-Evans (1995) describes a program at the University of Birmingham which is designed to raise awareness amongst research students of the rhetorical and linguistic conventions in journal articles and theses.

Issues Specific to Graduate Writing

A fundamental difference between undergraduate and graduate writing is the scale of the writing task (Torrence & Thomas 1994). Whereas most undergraduate writing is completed within weeks, possibly months, a gradu

202

Dissertation Writing in Action D. Allison et al.

203

ate dissertation will take 3-5 years and is likely to be in the region of 80 000 words plus. The nature of such a task places particular demands on the graduate writer, namely the need to sustain an argument over an extended piece of discourse and the need to review and revise what may have been written many months earlier. Yet, the issue of what this involves and how students can be helped to meet such demands has not been extensively addressed in the literature. Another difference between undergraduate and graduate writing arises from the expected audience for the writing. For undergraduates the situation is clear; the audience is the teacher. However, for the graduate writer the audience appears to be less clear. Shaw (1991), in investigating non-native speaker (NNS) science research students' dissertation composing processes at the University of Newcastle (UK), found a considerable amount of con fusion amongst the students in relation to the audience for whom they were writing. In answer to a question on the type of reader the students' envisaged, the two most common responses were: "the non-specialist with background knowledge" and "the subject-specialist" (Shaw 1991: 193). Shaw attributed this confusion partly to rather vague advice from supervisors and partly to the "pseudo-communicative nature of this task" (p, 194) which requires students to explain research to an already expert audience whilst at the same time "pretending to inform the sophisticated non-specialist" (p. 194). The issue of the expected audience for a dissertation is clearly one that needs to be recognized and addressed when working with graduate writers.

The Origins of the UHK Program

Universities in Asia are currently confronting a phenomenon which many Western tertiary educational systems have been dealing with for some time. This is the rapidly growing number of graduate students. The shift in focus that this growth has necessitated has placed pressure on resources, administration and, most particularly, upon supervisors. In Hong Kong, as elsewhere, the pressure has been increased by government requirements that completion rates be adhered to, and that students submit their dis sertations for examination within the maximum times specified by higher degree boards. Additionaltension arises in UHKfrom the fact that it is an English-medium university in a non-English speaking culture. In practical terms, this means that supervisors, approximately 50% of whom are themselves NNS of Eng lish, are required to supervise students who may be experiencing difficulty in communicating in written English in academic contexts. (Of the approxi mately 1500 graduate students at the University, over 70% are Cantonese speakers who have studied for their first degree in English, but a growing number each year are from mainland China.)

In a survey of 105 supervisors (20% of the total number) across all nine faculties in the university, it was found that 88% considered one or more of their students to have language problems; however, only 57% saw it as their responsibility to help students with these problems (Cooley & Lewkowicz 1995b).Virtually all the supervisors surveyed thought their students should be offered some form of assistance, such as through writing programs similar to those offered at universities in other parts of the world. The need for assistance was further underlined by findings from a survey of research students (362 questionnaire returns): 47% of respondents rated themselves as having moderate to severe writing difficulties (Cooley & Lewkowicz 1995a, 1995b). The university's association of graduate students had also expressed interest in the area of thesis writing and writing support, inviting speakers to give talks on this aspect of the research degree experience. In response to this situation, the School of Research Studies at UHK requested the English Centre to devise an instrument to assess graduate students' writing problems and put in place remediation measures. The writing specialists in the Centre decided that the assessment instrument should not take the form of a test, as this was inappropriate for graduate students in the UHK context. It should rather take the form of a profile that could give a student or supervisor information on the student's areas of difficulty (for details see Nunan et aI., in press). In order to establish this instrument, one obvious requirement was to identify what it was in the writing of research students that caused com prehension problems for readers, and whether these problems were com mon across different academic discipline areas. This was done through a detailed analysis of extended samples of student writing from a range of academic disciplines within the university. The analysis was also informed by the comments of writing consultants, including the authors, who had worked with UHKgraduate students on a one-to-onebasis. This also involved consulting with supervisors to ensure that we understood the research issues and the supervisors' own expectations as readers. The results of the discoursal analysis were synthesized with the results of a questionnaire on graduate students' self-perceptions of their own writing difficulties and data from interviews with supervisors on their perceptions of their students' writing problems. (See Cooley & Lewkowicz 1995a, 1995b for further details). This process resulted in the identification of four main problem areas in graduate students' writing, each divided into several sub-categories. These categories showed considerable similarity to the three areas of "com municative damage" identified by James (1984) in his study of graduate writers in the physical sciences, pure!applied sciences and social sciences at the University of Manchester (UK). The categories we identified were built into a framework, which we have termed the Diagnostic Assessment Profile (DAP). The profile, which is described below, was then used as a mechanism for commenting on a student's strengths and weaknesses in writing extended discourse. It was also used as a basis for developing a writing program to assist students.

204

D. Allison et aI.

Dissertation Writing in Action

205

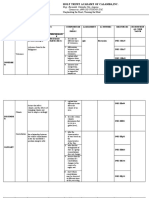

The Diagnostic Assessment Profile Although the sub-eategories are not discrete, for ease of reference when giving feedback, each sub-category was assigned to only one of the major sections of the framework, which move from larger, macro, to more detailed, micro, levels of analysis. (The framework itself is reproduced as Figure 1. A sample of a completed profile is given in Appendix A)

I. Overall Communicative Success

[] Purpose

[ 1Audience (explicitness)

[ ) Organization

[ ) Consistency of argument

[] Balance

II. Substantiation [How well own assertions are substantiated (through argument and/or evidence) and how supporting material is incorporated into the work) [ ) Use of sources

[ ) Status of claims

[ ) Citations

III. Discourse Elements/Features [How information is distributed and relationships between concepts and entities are introduced, developed and tracked] [ ] Signposting [ ] Topic development [ ) Clause structure [) Cohesion [ ] Grammatical choices [ ] Lexis IV. Editing [ ) Local grammatical forms [ ] Spelling [ ) Punctuation [ ) Word forms [ ) Bibliography Comments:

Comments:

Comments:

Comments:

Figure 1: The Diagnostic Assessment Profile The first section (I) provides an analysis of the overall communicative success of the piece of writing, and assesses it in terms of the clarity of purpose, the extent to which the audience is addressed, the extent to which the overall organization of the dissertation, chapter, or sub-section of chapter facilitates understanding for the reader, the consistency of the argument, and the overall balance of content. This is by far the most important section of the framework, when it comes to the effective communication of meaning. In most instances, when confronted with a piece of writing where the mean ing was unclear, the reason had to do with lack of overall organization, lack of clarity of purpose, lack of explicitness of audience or inconsistency of argument. The second section (II) focuses on substantiation. Here the focus is on how convincingly the writer has created a research "space" from an analysis of the literature (Swales 1990). At this level, we are also concerned with

I,

" I

how the writer's own assertions are substantiated, through argument and evidence, and how supporting material is incorporated into the work. Section three (III) is concerned with how information is distributed, and how relationships between concepts and entities are introduced, related to one another, developed, and tracked through the discourse. Here, the con cern is with the effectiveness with which the writer has dealt with discourse features and elements such as topic development, cohesion, signposting, clause structure, grammatical choices, and lexis. The final section (IV) deals with editing, and is concerned with local grammatical forms, spelling, punctuation, bibliographical references and so on. Interestingly, it seems that while errors and problems at this level are the first to come to the attention of the reader, and are frequently irritating, they rarely obscure meaning, a point which was mentioned by several of the supervisors in the survey. Once the assessment instrument had been devised and the scale of the required measures became apparent, it was clear that the English Centre had to augment its existing Writing Support Service, intended for one-to-one student consultations on a voluntary basis or upon referral by a supervisor. A writing program needed to be devised which would provide cost-effective assistance on a wider scale, since a one-to-one service could not possibly offer assistance to all the graduate students with writing difficulties. At first, it was felt that an existing program could be adapted for use within the University. However, existing programs tend to require students to complete short writing tasks unrelated to their research. They thus fail to provide insights into what it is that causes communication problems in the extended writing required to produce an entire thesis and also do not allow students the opportunity to focus on problems in their own writing. For research students there is a constant tension between progressing with their research and taking time out to improve their writing skills. Writing programs therefore need to assist students with the writing they are already doing, rather than requiring them to carry out additional writing tasks which they may perceive as irrelevant to their needs. Such considerations led to the conclusion that adaptation of an existing model would not provide a suitable writing program for the graduates at UHK The program to be devised would need to offer assistance to graduate students working in a wide range of disciplines from medicine to education, from dentistry to law. It would also need to provide a way of focusing on the students' own writing and to raise awareness of the communication demands peculiar to an extended piece of academic writing. At the same time, it had to be recognized that the progam could only be offered on a voluntary basis and that students registering for the course would be at varying stages of writing their own dissertation and of varying competence in written English.

The Program in Action

Having concluded that existing programs were unsuitable as the basis for our graduate students' writing program, the writing consultants at the Eng

206

D. Allison et aI.

Dissertation Writing in Action

207

lish Centre decided that the DAP would form an appropriate framework for a program because it had been developed from an analysis of those areas which caused the greatest problems for dissertation writers. Raising aware ness of important issues in dissertation writing was, therefore, taken as the overall aim of the program. The program consisted of five three-hour workshops, during which stu dents were introduced to the main areas of concern in dissertation writing, through the DAP. They were also introduced to the idea of using the framework to analyze their own writing. Each workshop was made up of a lecture followed by a tutorial. In the lectures, the key elements in the Profile were introduced and exemplified. Then, in the tutorials, students had an opportunity to engage in tasks based on writing samples provided, as well as to analyze and discuss their own writing with other members of the group, focusing on how successful their writing was in terms of the DAP. In the first workshop, students were introduced to the DAP and to unfam iliar terminology, The second workshop concentrated on the Overall Com municative Success component of the DAP. Here we placed considerable emphasis on making research questions and findings intelligible in general terms to non-specialist readers. On this issue, evidence suggests that there is a variety of opinion amongst both research students and supervisors (Shaw 1991). Some supervisors advise their students to write for an expert in a parallel area, whilst others recommend writing for a non-specialist with background knowledge and students are, naturally, influenced by this advice. Our team is of the opinion that articulating the goals and value of a research study is an important aspect of any academic communication if researchers wish a wide audience to benefit from their findings. We see this concern for intelligibility as compatible with the need to ensure that research content is also addressed convincingly to an insider audience. A clear example of the importance of making the purpose and significance of the research clear was presented and discussed during the workshop tutorials. The example came from a civil engineering doctoral study (now successfully completed) in which the research question had concerned the safety of steep slopes, a conspicuous feature of the Hong Kong landscape. IThe aim of the research had been to improve on earlier mathematical modelling of factors associated with the collapse of steep slopes. The aim, however, had been quite deeply buried in a wealth of background infor mation with the writer giving no indication of research direction for 18 pages. Earlier and more prominent presentation of the purpose and import of the research had therefore been recommended in comments on the draft land was endorsed by the supervisor on seeing the student's revised work. is did not imply any expectation on our part that the actual complexities ofthe mathematical modelling should be made intelligible to people without !therelevant mathematical background, which would not have been realistic. The remaining three workshops covered the sections of the DAP involving more detailed appraisal of specific aspects of the overall message, although e did not followthe exact sequence ofthe stages in the DAP (substantiation,

discourse elements/features, editing). Instead, we spent two sessions on discourse features, one concentrating on signposting and topic development, the other on lexical, grammatical and cohesive choices. These were related to the consistency and development of the argument or treatment of material in extended writing. Important questions of strength and justification of claims, often a problematic area for students and others at all levels of academic writing (Allison1995;Hyland 1994;Johns 1993; Myers 1985, 1989; Skelton 1988; Swales 1987, 1990) were covered in the last session along with the use of sources and editing. Care was always taken to stress that, as many of these features are discipline-specific, extensive reading in the discipline area was essential in order for students to become sufficiently familiar with accepted conventions. The initial series of workshops took place over a period of four months. The reasons for this prolonged period were two-fold. As participants in the workshops had been asked in advance to bring extended samples of writing to the first session and it was anticipated that these samples would be lengthy and often extremely complex for the non-specialist to understand, it was considered that tutors would need several weeks between sessions to assess the work and to make arrangements for providing feedback to stud ents. It was also felt that spacing out the workshops would allow the students to digest the input sessions, and to produce more writing, or to redraft earlier versions in light of peer and tutor feedback.

Evaluating the Program

The end of course evaluation data provided by those participants who completed the course was highly positive. Quantitative responses to the relevance of the course objectives and whether these were met are set out in Table 1. Students were also invited to list up to three aspects of the workshops which they found most useful and three they found least useful. Not sur prisingly the 21 respondents came up with a wide range of responses. But what is worthy of note is that, whereas most respondents noted two or three aspects of the workshops which they found most useful, the total number of responses being 49, there were only 15 responses under the least useful category, that is less than one aspect noted per respondent. Despite the generally positive feedback from the participants who com pleted the first series of workshops, there were a number of evident prob lems and difficulties. Many of these problems appeared to arise from the organization of the workshops and it is to a review of these that we now

tum.

Organizational Problems

One of the major causes of concern was the high attrition rate; only 21 of the original 105 students registered completed the series of workshops. This

208

D. Allison et al.

Dissertation Writing in Action

209

TABLE 1 Quantitative Responses Regarding the Relevance of Objectives and the Extent to Which These Were Met

Objectives;

Were they met? (l =not at all; 4=fully) 1 2 1 3 9 14 4 11 6

Were they relevant? (l=not at all; 4=fully) 1 2 3 11 2 11 4

10

NR

Raise awareness of good thesis writing practice Show how overall communicative success is achieved Demonstrate the need for sign posting in written texts Demonstrate how topics are developed in academic English Raise awareness of factors affecting grammatical choice Explain which features of text contribute to its cohesion Raise awareness of the importance of vocabulary choices Raise awareness of the need for and methods of substantiation Raise awareness of the need for and methods of editing 1

12 2 16

9 3

1 4

9 13

11 4

-'l

11

3 6

13

2 7 1

5

3

10 13

4 4

11

10

10

and critique the writing of others. Some students, particularly those who were at an early stage of their research, had not begun to write, and many of those who had were reluctant to share their writing with others, possibly due to lack of confidence. Although there are good arguments for having students work on their own writing, the diversity of the writing samples that students brought to the tutorials, if they brought anything at all, made this extremely difficult, and in a number of respects, those tutorials which were organized around a common body of material were the more successful ones. In the second and subsequent series of workshops, we have provided texts, either extracts from students' writing or from published journal articles, for discussion by small groups and this has proved to be a more successful format. Using a core of writing samples seems to have allowed for more productive dis cussion among students and exposed students to a range of points illustrated in the input sessions. It has also, perhaps, reinforced the idea of the import ance of making one's writing clear to a non-expert but interested reader. One more organizational problem related to the size of the original group. With 105 students present, it was necessary to adopt a lecture format for the input sessions. But tutors felt that the consequent lack of immediate interaction on points covered weakened the impact of the ensuing discussions. In subsequent workshops, numbers have been limited to a maximum of 40 and the three hour blocks are divided into two sections, each consisting of a short input session followed by small group discussions of texts illustrating the points introduced, with two or three teachers team teaching. This format has been positively evaluated by course participants.

10

The Use of the DAP as a Basis of Organization

The use of the framework as a basis for organizing the workshops helped focus students on those organizational and textual aspects of a dissertation that need to be taken account ofin order to produce work that is linguistically acceptable. Using the framework as the basis of the workshop gave a coher ence to the course that it may otherwise have lacked. It enabled tutors (and hopefully students) to make connections among different kinds of writer choice, such as the thematic, the grammatical and the lexical, and enabled links to be drawn between these and more general issues of topic devel opment and audience awareness. In all the series of workshops run so far, the vast majority of students have evaluated the use of the DAP as an organizing principle to be moderately useful to very useful. However, the extent to which students are able to use the framework by themselves to analyze samples of their own writing remains uncertain. It may be worth while developing a "user's guide" to the framework. This would serve the dual purpose of glossing the key terms and concepts in the framework, as well as providing the user or potential user with a set of operational pro cedures for evaluating their writing against the framework. A guide would also be necessary for supervisors if they were to use the framework without

N=21.

high rate appears to have been the result of spacing the sessions out over a four-month period. Responses to a questionnaire sent out to those who did not complete suggest that students found it difficult to commit themselves to specific dates so far in advance and were unable to complete the course when their plans had to be changed unexpectedly. The five contact sessions had been spaced out with the intention of enabling students to put into practice the points raised, and insights generated during the lectures and tutorials. Later workshops run in more intensive mode (once a week, twice a week, or on six consecutive days) showed very low attrition rates of between 4% and 17%. This seems to suggest that for this type of awareness raising program, the intensive mode for fewer participants is preferable. A further problem during the first series of workshops was the fact that students were at very different stages in their research. Some had almost completed their dissertations, while others were just beginning their research. This created numerous difficultieswhen it came to tutorials, which were designed for participants to work on their own writing, and to review

210

D. Allison et al.

Dissertation Writing in Action

211

any formal introduction to it. A set of evaluative questions have already been developed for the first level of the framework (I) which could be used by students working alone to assess the overall success of their writing. (These evaluative questions are reproduced as Appendix B.)

Final Reflections

The program made considerable demands on the tutors. In the first place, they were required to read and develop a working understanding of lengthy extracts from students' dissertations. The dissertations were from a wide variety of disciplines, from civil and structural engineering to psychiatry. Having to respond critically to lengthy extracts from theses in a wide range of disciplinary areas was extremely demanding. The nexus between language and content also underlined the dilemma for EAP teachers who are not subject specialists. An additional, although related, problem was that different discipline areas appear to have different evaluative criteria, make different assumptions, and impose different demands on their students. Tutors, bringing the evaluative criteria of applied linguistics and language education to engineering or architecture ran the risk of being either too stringent or too lax in their approach. This became apparent in a session in which the tutors addressed the issue of audience, and suggested that a thesis ought to be written in a way which made its main concerns accessible to reasonably well-informed non-specialists. The justification for this claim derives from an increasing recognition on the part of research communities that research should be made more widely intelligible, in outline, in the interest of accountability. (See also Belcher 1995 on the importance given to wider audiences in critical reviewing.) This view, however, was disputed by a minority of students on the course, particularly some from engineering and science who believed that their readers would be specialists in their field of study and hence that clarification and exemplification would be unnecessary. These students were reluctant to accept that they themselves would become the expert and that even their examiners might appreciate, or even need, help and guidance through the text (see also Benson & Heidish 1995on the ESL technical expert). This, as has been alluded to earlier, may be partly a result of supervisors' expec tations, but it may also be a difference between academic writing in English and Chinese. Shaw (1991) notes the observation of one of his Chinese graduate students that "in China the dissertation is intended for an expert, so not much explanation is necessary" (p. 194). Silvaet al. (1994), discussing an obligatory taught course for a small number of graduate writers identified as most in need of writing instruction, report comparable reactions among their students to assignments on writing research proposals. In the final analysis it is for students to decide whether to accept wider intelligibility as appropriate for their dissertation writing. While we are conscious of the difficulties that EAP teachers face as "lay" readers of specialist writing, an issue much discussed after Spack (1988),

we would not want to distance ourselves from the content domains in which graduate researchers are seeking to master academic writing in English. We find that EAP teachers can still offer useful commentaries as informed outsiders, who are familiar with a range of academic writing and able to articulate reader reactions to such writing. It is the students themselves who, in seeking our responses to their writing, authenticate our role as one audience for this writing and either accept our comments or take issue with them. In such a context, we see no danger of EAP teachers "appropriating" what students write (see Reid 1994 and Hall 1995 for discussion of this issue): tutors' comments, and comments by other students, offer writers some feedback to consider. We would accept that "the judging of discipline based writing by nonmembers of the discipline remains problematic" (Hamp-Lyons 1991: 144). However, we see this as far less prejudicial when these judgements are not being exercised as part of formal procedures of assessment, but are part of an on-going dialogue between the graduate student and language consultant in a situation where the student is in a position to accept or reject the advice given. The issue of how accessible a specialist text should be to a lay reader is probably most usefully explored in the workshops through reference to actual examples of highly specialised content in which the research questions and rhetorical intent remain access ible to lay readers. Tutors and other students were often able to identify and comment on such instances. A moral dilemma which tutors had to confront had to do with the fact that some research proposals were marred by poor research design. In a number of instances it did not require detailed content knowledge to see that there were threats to the reliability and validity of the research proposals. As tutors had no mandate to comment on substantive and procedural issues to do with the research process itself, they had to proceed with great care. It was not desirable either to leave students to proceed with faulty research designs, or risk major conflicts with faculties which would have jeopardized the entire writing program. At most, a tutor might seek some clarification concerning the statement of goals and the direction of the research, or concerning apparent inconsistencies in presentation, thereby incidentally pointing a student towards associated issues of substance. Peer discussion in the homogeneous groups also sometimes addressed more substantive issues in what appeared to be valuable exchanges on research design. Consideration must also be given to the advisability of running discipline/ faculty specific workshops in future. The original decision not to do so was founded not only on practical considerations of funding for small groups (although this is, of course, important) but on the finding that the same type of writing problems seemed to be common across disciplines. However, the evaluation forms at the end of each series of workshops suggest that the science students, although relating positively to the workshops, find the objectives less relevant to their own writing needs than students in the other faculties. The results for the first four series of workshops show that 27% of the science students regarded the objectives to be "very relevant" and 73%

212

D. Allison et aI.

Dissertation Writing in Action

213

"moderately relevant" as compared to 88% of arts students who considered the objectives "very relevant" and 12% "moderately relevant". The reasons for this were not readily apparent from other responses on the questionnaires and clearly further research into this area is necessary.

already been implemented in subsequent workshops at UHK and research is continuing into ways in which students can be assisted further with the challenging task of writing a dissertation in a second or foreign language. Yet we believe that the focus on extended texts and the macro-level of writing as emphasized in this paper are essential if students are to go beyond improving their writing at the sentence level and actually enhance the quality of their dissertation writing.

Conclusion

Research amongst supervisors and graduate students at UHK, the num bers of students registering for the writing program that was introduced, students' positive reactions to the program and the growing number of graduate students attending the English Centre's one-to-one Writing Support Service have combined to show that there is clearly a need for a writing program to become a regular feature of graduate life at the university. In this paper, we have described the development of a program to help NNS research students develop skills in planning, drafting, and revising their theses. The program evolved from a grounded investigation into the problems encountered by students in their struggle to produce a thesis in a language other than their own. Data for this investigation came from inter views with supervisors, students' questionnaires and an analysis of student writing. The initial study, as indicated above, revealed shortcomings in four main areas which can be summarized as follows: 1. a failure to organize and structure the thesis in a way which made the objectives, purpose and outcomes of the research transparent to the reader, and a failure to create a "research space"; 2. a failure to substantiate arguments with evidence from the literature and a tendency to make claims for own research findings which were too strong or overgeneralized; 3. an inability to organize information at the level of the paragraph, to show relationships and to develop texts in functionally appropriate ways; 4. "local" problems to do with editing, spelling, grammar and bib liographical referencing. While, at first sight, local errors were the most evident, by far the greatest number of communication problems occurred at the macro-level of audience, purpose and overall structuring. Hence the diagnostic framework and the resultant writing program were designed to focus primarily on these macro level problems. A limitation of the work that has been reported here is its situation-specific nature-although this is in some ways a strength. While we have expressed a degree of confidence that the approach we have described will be appli cable in work with NNS research students in other situations, we are sure that adaptations will prove to be necessary. Indeed, some changes have

(Revised version received December 1996)

REFERENCES

Allison, D. M. (1995). Assertions and alternatives: Helping ESL under graduates extend their choices in academic writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 4, 1-15. Belcher, D. (1994). The apprenticeship approach to advanced academic literacy: Graduate students and their mentors. English for Specific Purposes, 13, 23-34. Belcher, D. (1995). Writing critically across the curriculum. In D. Belcher & G. Braine (Eds.) , Academic writing in a second language (pp. 135-154). Norwood, N]: Ablex. Benson, P., & Heidish, P. (1995). The ESL technical expert: Writing pro cesses and classroom practices. In D. Belcher & G. Braine (Eds.), Aca demic writingin a second language (pp. 313-330). Norwood, N]: Ablex. Brown, R. (1994). The "Big Picture" about managing writing. In O. Zuber Skerritt & Y. Ryan (Eds.), Quality in graduate education (pp. 90-109). London: Kogan Page. Casanave, C. P., & Hubbard, P. (1992). The writing assignments and writing problems of doctoral students: Faculty perceptions, pedagogical issues, and needed research. English for Specific Purposes, 11, 33-49. Cooley, L., & Lewkowicz, J. (1995a). Graduate students' writing needs and difficulties. Unpublished report (20 pp.), School of Research Studies, Uni versity of Hong Kong. Cooley, L., & Lewkowicz, J. (1995). The writing needs of graduate students' at the University of Hong Kong: A project report. Hong Kong Papers in Linguistics and Language Teaching, 18, 121-123. Dudley-Evans, T. (1995). Common-core and specific approaches to the teach ing of academic writing. In D. Belcher & G. Braine (Eds.), Academic writing in a second language (pp. 293-312). Norwood, N]: Ablex. Frodesen,]. (1995). Negotiating the syllabus: A learning-centered, inter active approach to ESL graduate writing course design. In D. Belcher & G. Braine (Eds.), Academic writing in a second language (pp. 331-350). Norwood, N]: Ablex.

i~

214

. D. Allison et al.

Dissertation Writing in Action

215

Hall, C. (1995). Comments on Joy Reid's responding to ESL students' texts: The myth of appropriation. TESOL Quarterly, 29, 159-163. Hamp-Lyons, L. (1991). Reconstructing "academic writing proficiency". In L. Hamp-Lyons (Ed.), Assessing second language writing in academic con texts (pp. 127-153). Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Hyland, K. (1994). Hedging in academic writing and EAP textbooks. English for Specific Purposes, 13, 239-256. James, K. (1984). The writing of theses by speakers of English as a Foreign Language: The results of a case study. In R. Williams (Ed.), Common ground: Shared interests in ESP and communication studies (ELT Docu ments 117). Oxford: Pergamon. Johns, A M. (1993). Written argumentation for real audiences: Suggestions for teacher research and classroom practice. TESOL Quarterly, 27, 75 90. Myers, G. (1985). Texts as knowledge claims: The social construction of two biology articles. SocialStudies of Science, 15, 593-630. Myers, G. (1989).The pragmatics of politeness in scientific articles. Applied Linguistics, 10, 1-35. Nunan, D., Lewkowicz, ]., & Cooley, L. (in press). Evaluating graduate students' writing. In E. Lee & G. James (Eds.), Proceedings of the 1995 Testing and Evalustion of Second Language in Education Conference. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Reid, ]. (1994). Responding to ESL students' texts: The myths of appro priation. TESOL Quarterly, 28, 273-292. Richards, R. (1988). Thesis/dissertation writing for EFL students: An ESP course design. English for Specific Purposes, 7, 171-180. Shaw, P. (1991). Science research students' composing processes. English for Specific Purposes, 10, 189-206. Silva, T., Reichelt, M., & Lax-Farr, I. (1994). Writing instruction for ESL graduates: Examining issues and raising questions. ELTJournal,48, 197 204. Skelton,]' (1988). The care and maintenance of hedges. ELT Journal, 42, 37-43. Spack, R. (1988). Initiating ESL students into the academic discourse com munity: How far should we go? TESOL Quarterly, 22,29-51. Swales,]' M. (1987). Utilizing the literatures in teaching the research paper. TESOL Quarterly, 21,41-68. Swales, ]. M. (1990). Genre analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Swales, ]. M. (1995). The role of the text book in EAP writing research. English for Specific Purposes, 14, 3-18. Swales.I. M., & Feak, C. B. (1994a).Academicwritingforgraduatestudents: A course for nonnativespeakers ofEnglish. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Swales, J. M., & Feak, C. B. (1994b). Academic uiritingforgraduatestudents: Commentary. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Torrence, M. S., & Thomas, G. V. (1994). The development of writing skills in doctoral research students. In R. G. Burgess (Ed.), Postgraduate education and training in the social sciences. London: Jessica Kingsley Publications. Trimble, L. (1985). English for Science and Technology: A discourse approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Appendix A

A sample of a completed Diagnostic Assessment Profile

I. Overall Communicative Success [X 1Purpose [ X 1Audience (explicitness) [ X 1Organization [ X 1Consistency of argument [n.a] Balance

Comments:

What is being studied seems at first clear,

but why is not stated and gradually what

becomes unclear.

Audience not clear. No sense of logical

development. No consistency of argument.

II. Substantiation [How well own assertions are substantiated (through argument and/or evidence) and how supporting material is incorporated into the work] [ X 1Use of sources [ X 1Status of claims [ X 1Citations

Comments:

No assessment of sources. Quotations

seem to be taken out of context.

III. Discourse Elements/Features (How information is distributed and relationships between concepts and entities are introduced, developed and tracked) [ X 1Signposting [ X ] Topic development [ .; 1Clause structure [ X 1Cohesion [ .; ] Grammatical choices [X 1Lexis

Comments:

Vocabulary and style informal and

journalistic. No indications given of

organization, nor relationship between

parts. Topic frequently changes within one

paragraph. Connections between sentences

not clear.

IV. Editing [ .; ] Local grammatical forms [.; 1Spelling [ .; 1Punctuation [ .; 1Word forms [ X ] Bibliography

Comments: References confusing. Not clear which are journals and which are books, nor which are first names and which are surnames. Many articles missing.

216

D. Allison et aI.

Dissertation Writing in Action

217

AppendixB

Determining the Overall Communicative Success (I)

Purpose: Is the purpose of the research clearly stated at the outset? Are central constructs adequately defined? Has the need for this research been clearly established? Are the research questions explicitly stated? Are the questions answerable? Are they appropriate for MPhil/PhD? Does the researcher create, contest or apply a theoretical model appropriate to the research domain in question? Audience: Is the general purpose and justification for the research clear to the non-specialist? Does the work assume knowledge which would only be accessible to someone with a PhD in the area concerned?

and programme evaluation, as well as questions of academic writing, par ticularly at the postgraduate dissertation level.

1

t

"

David Nunan is Professor ofApplied linguistics and Director ofthe English Centre at the University of Hong Kong. Prior to this, he was Director of Research and Development, NCELTR, and Coordinator of Postgraduate Programs in Linguistics at Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia. Pro fessor Nunan has published over 100 books and articles in the areas of curriculum and materials development, classroom-based research, and dis course analysis.

Organization:

How is the text organized? Is the organization consistent with the overall purpose of the research? Is the organization of the dissertation, chapter or section signalled in the introduction? Are "facts" synthesized and related to theoretical constructs/models?

Consistency of argument: Are central concepts and constructs underlying the research operationally defined? Is their deployment in the writing consistent with the way in which they have been operationalized? Is there consistency in the research outcomes on which the research is based? If not, does the writer evaluate and adjudicate on conflicting findings? Are the arguments of the writer consistently presented? Balance: Is the relative weighting and emphasis given to points, issues, subsections, etc. appropriate, given the overall purpose of the research? Are threats to internal and external reliability and validity of the research acknowledged?

Desmond Allison is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of English lan guage and Literature, National University of Singapore. Previously he was Academic Coordinator of the English Centre, the University of Hong Kong. His interests include comprehension studies, discourse and genre analysis (especially academic writing) and language programme evaluation.

linda Cooley is a Language Instructor in the English Centre at the Uni versity of Hong Kong. She has previously taught English in Tunisia, Yemen and Korea. Her interests include genre analysis, coherence and cohesion in academic writing, particularly in the area of postgraduate thesis writing, and oral presentation skills.

Jo Lewkowicz is a Lecturer in the English Centre at the University of Hong Kong. Prior to taking up her present appointment, she worked in China, Kenya, Egypt and Poland. Her research interests include language testing

1!~;'

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Field Study Course DescriptionDocument75 pagesField Study Course DescriptionErna Vie ChavezPas encore d'évaluation

- AUC Conversation CourseDocument3 pagesAUC Conversation CourseRashad M. El-Etreby100% (1)

- A Positive Behavior Intervention-S Effect On Student Tardiness ToDocument32 pagesA Positive Behavior Intervention-S Effect On Student Tardiness ToPJ PoliranPas encore d'évaluation

- Female Reproductive System LessonDocument26 pagesFemale Reproductive System LessonMarivic AmperPas encore d'évaluation

- Maguinao ES Science Class on EnergyDocument4 pagesMaguinao ES Science Class on EnergyCherry Cervantes HernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Holy Triniy Acadamy of Calamba, Inc.: Shepherding The Heart, Training The MindDocument3 pagesHoly Triniy Acadamy of Calamba, Inc.: Shepherding The Heart, Training The MindChristine Ainah Pahilagao SalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Work Motivation Lesson PlanDocument1 pageWork Motivation Lesson PlanDorothy Kay ClayPas encore d'évaluation

- The Benefits of HandsDocument2 pagesThe Benefits of HandsMark Anthony ORAAPas encore d'évaluation

- Google Classroom Formative Assessment ReportDocument9 pagesGoogle Classroom Formative Assessment Reportchs076 Maria AlkiftiahPas encore d'évaluation

- Common Behavior Problems in The ClassroomDocument2 pagesCommon Behavior Problems in The ClassroomJaycel Abrasado DaganganPas encore d'évaluation

- Artificial Adaptive Agents in Economic TheoryDocument7 pagesArtificial Adaptive Agents in Economic TheoryBen JamesPas encore d'évaluation

- Grade 9 lesson on "While the Auto WaitsDocument2 pagesGrade 9 lesson on "While the Auto WaitsMire-chan BaconPas encore d'évaluation

- Asca Lesson Plan - Stress Management 2Document4 pagesAsca Lesson Plan - Stress Management 2api-284032620Pas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Social Innovation and ChangeDocument4 pagesUnderstanding Social Innovation and ChangeWeeraboon WisartsakulPas encore d'évaluation

- Service Design Toolkit Process TemplatesDocument19 pagesService Design Toolkit Process TemplatesSebastian Betancourt100% (6)

- BOSCH INTERNSHIP REPORT Part 3Document5 pagesBOSCH INTERNSHIP REPORT Part 3Badrinath illurPas encore d'évaluation

- Synthesis Definition PsychologyDocument8 pagesSynthesis Definition Psychologyafbteuawc100% (1)

- Thesis 2Document37 pagesThesis 2Charmaine Dela CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- RPHDocument3 pagesRPHLau Su EngPas encore d'évaluation

- Differences Between L1 and L2 AcquisitionDocument2 pagesDifferences Between L1 and L2 AcquisitionYazid YahyaPas encore d'évaluation

- School Board PresentationDocument18 pagesSchool Board PresentationMicheleGrayBodinePas encore d'évaluation

- A Teachers Dozen-Fourteen General Research-BasedDocument10 pagesA Teachers Dozen-Fourteen General Research-BasedeltcanPas encore d'évaluation

- Gifted and TalentedDocument2 pagesGifted and Talentedapi-242345831Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edtpa Assessment CommentaryDocument7 pagesEdtpa Assessment Commentaryapi-303432640Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sti CollegeDocument9 pagesSti Collegejayson asencionPas encore d'évaluation

- Annual Implementation Plan 2023-2024Document15 pagesAnnual Implementation Plan 2023-2024ArmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Improving Speaking Accuracy Through AwarenessDocument7 pagesImproving Speaking Accuracy Through AwarenessJosé Henríquez GalánPas encore d'évaluation

- Prior Knowledge MathsDocument3 pagesPrior Knowledge Mathsapi-518728602Pas encore d'évaluation

- Coping with Stress and Maintaining Mental HealthDocument5 pagesCoping with Stress and Maintaining Mental HealthMavelle FamorcanPas encore d'évaluation

- Practise Unit 2 2.1Document15 pagesPractise Unit 2 2.1Leader KidzPas encore d'évaluation