Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Why Women Live Longer Than Men

Transféré par

Kavitha Bahu ReddyDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Why Women Live Longer Than Men

Transféré par

Kavitha Bahu ReddyDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Why Women Live Longer than Men

By William J. Cromie Gazette Staff Studying people who live 100 years and more leads Harvard researchers to conclude that menopause is a major determinant of the life spans of both women and men. Women's life span depends on the balance of two forces, according to Thomas Perls, a geriatrician at Harvard Medical School. One is the evolutionary drive to pass on her genes, the other is the need to stay healthy enough to rear as many children as possible. "Menopause draws the line between the two," Perls says. It protects older women from the risks of bearing children late in life, and lets them live long enough to take care of their children and grandchildren. As for men, Perls believes "their purpose is simply to carry genes that ensure longevity and pass them on to their daughters. Thus, female longevity becomes the force that determines the natural life span of both men and women." "Most animals do not undergo menopause," adds Ruth Fretts, an obstetriciangynecologist at Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. "It seems that menopause evolved in part as a response to the amount of time that the young remain dependent on adults to ensure their survival." Pilot whales, for example, suckle their young until age 14, and they, along with humans, are two of the few species that menstruate. Human females eventually become so frail that bearing children involves a high risk of death. Earlier in evolution, that was as young as 35 to 40 years old. "Anyone who developed a genetic alteration that caused infertility, i.e., menopause, obtained a survival advantage over females who continued to be fertile and died bearing children," Perls says. The Gender Gap This reasoning, however, does not explain why women live so much longer than men. "In all developed countries and most undeveloped ones, women outlive men, sometimes by a margin of 10 years," Perls and Fretts note. "In the U.S., average life expectancy at birth is about 79 years for women and about 72 years for men." The gender gap is most pronounced in those who live 100 years or more. Among centenarians worldwide, women outnumber males nine to one. Perls and Fretts are

studying all centenarians from eight cities and towns around Boston, 100 people in all. Eighty-five are women. The mortality gap varies during other stages of life. Between ages 15 and 24 years, men are four to five times more likely to die than women. This time frame coincides with the onset of puberty and an increase in reckless and violent behavior in males. Researchers refer to it as a "testosterone storm." Most deaths in this male group come from motor vehicle accidents, followed by homicide, suicide, cancer, and drownings. After age 24, the difference between male and female mortality narrows until late middle age. In the 55- to 64-year-old range, more men than women die, due mainly to heart disease, suicide, car accidents, and illnesses related to smoking and alcohol use. Heart disease kills five of every 1,000 men in this age group. "It seems likely that women have been outliving men for centuries and perhaps longer," say Perls and Fretts. Even with the sizable risk conferred by childbirth, women have outsurvived men at least since the 1500s. Although, in the United States between 1900 and the 1930s, the death risk for women of childbearing age was as high as that for men. Since then, improved health care, particularly in childbirth, has put women ahead of men again in the survival struggle, as well as raising life expectancy for both sexes. A longer life doesn't necessarily mean a healthier life, however. While men succumb to fatal illnesses like heart disease, stroke, and cancer, women live on with non-fatal conditions such as arthritis, osteoporosis, and diabetes. "While men die from their diseases, women live with them," Perls comments. One contributor to the gender difference in life span is the influence of sex hormones. The male hormone testosterone not only increases aggressive and competitive behavior in young men, it increases levels of harmful cholesterol (lowdensity lipoprotein), raising a male's chances of getting heart disease or stroke. On the other hand, the female hormone estrogen lowers harmful cholesterol and raises "good" cholesterol (high-density lipoprotein). Emerging evidence suggests estrogen treatment after menopause reduces the risk of dying from heart disease and stroke, as well as of dying in general. Perls and Fretts believe that longer life means survival of the fittest, and women, evolutionarily speaking, are more fit than men. The longer a woman lives and the more slowly she ages, the more offspring she can produce and rear to adulthood. Therefore, evolution would naturally select the genes of such women over those who die young.

Long-lived men would also have an evolutionary advantage over their shorterlived brethren. However, says Perls, "studies of chimps, gorillas, and other species closely related to humans suggest that a male's reproductive capacity is actually limited more by access to females than by life span. And because men have not been involved in child care as much as females, survival of a man's offspring, and thus his genes, depended not so much on how long he lived, but on how long the mother of his children lived." In their studies of centenarians, Perls and Fretts found that a surprising number of women who lived to be 100 or more gave birth in their forties. These 100-year-old women were four times as likely to have given birth in their forties as women born in the same year who died at age 73. A study of centenarians in Europe by the Max Planck Institute of Demography in Germany found the same relationship between longevity and fecundity. This does not mean that having a child in middle age makes a woman live longer. Rather, Perls says, "the factors that allow certain older women to bear children -- a slow rate of aging and decreased susceptibility to disease -- also improve a woman's chances of living a long time. Extending that idea, we argue that the driving force of human life span is maximizing the time during which woman can bear children. The age at which menopause eliminates the threat of female survival by ending further reproduction may therefore be the determinant of subsequent life span." Closing the Gap If this is true, then the genes of female centenarians hold the secrets of a longer, healthier life. And these are no ordinary genes. Whether the average person drinks, smokes, exercises, or eats her vegetables adds or subtracts five to ten years to or from her life. But to live an additional 30 years requires the kind of genes that slow down aging and reduce susceptibility to conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, stroke, heart disease, and cancer. Clues about what those genes are and how they work could come from studying those who survive 100 years or more, Perls believes. The New England Centenarian Study he runs is the only scientific investigation of the oldest oldsters being done in the United States. He has now expanded it to include all centenarians in the city of Boston, about 100 more people. "We think that centenarians are a tremendous resource for the discovery of genes responsible for aging and the ways in which aging occurs," says Perls. "Finding these genes could lead to testing people and determining who might be disposed to accelerated aging via diseases such as Alzheimer's, cancer, heart disease, and stroke. Such individuals might eventually be treated to extend the prospect of their living longer."

The oldest person for which reliable records exist was a woman who recently died in France at the age of 123. "Reaching such an age is like winning the lottery," Perls comments. "The odds are about one in 6 billion. From a practical point of view, we can consider 100 years as the average maximum of human life. We're not there yet, of course. At present, average life expectancy for those born after 1960 is about 85 years." Although women can expect to live longer than men, the gap is closing. Death rates have begun to converge in the past 20 years. Some researchers attribute the convergence to women taking on the behaviors and stresses formerly considered the domain of males -- smoking, drinking, and working outside the home. For example, Perls and Fretts point out that deaths from lung cancer have almost tripled in women in the past 20 years. One study concluded that, on average, middle-aged female smokers live no longer than male smokers. "Smoking," Perls and Fretts conclude, "seems to be the 'great equalizer.'"

If there are any men left who still believe that women are the weaker sex, it is long past time for them to think again. With respect to that most essential proof of robustnessthe power to stay alivewomen are tougher than men from birth through to extreme old age. The average man may run a 100-meter race faster than the average woman and lift heavier weights. But nowadays women outlive men by about five to six years. By age 85 there are roughly six women to every four men. At age 100 the ratio is more than two to one. And by age 122the current world record for human longevitythe score stands at one-nil in favor of women. So why do women live longer than men? One idea is that men drive themselves to an early grave with all the hardship and stress of their working lives. If this were so, however, then in these days of greater gender equality, you might expect the mortality gap would vanish or at least diminish. Yet there is little evidence that this is happening. Women today still outlive men by about as much as their stay-at-home mothers outlived their office-going fathers a generation ago. Furthermore, who truly believes that mens work lives back then were so much more damaging to their health than womens home lives? Just think about the stresses and strains that have always existed in the traditional roles of women: a womans life in a typical household can be just as hard as a mans. Indeed, statistically speaking, men get a much better deal out of marriage than their wives married men tend to live many years longer than single men, whereas married women live only a little bit longer than single women. So who actually has the easier life? It might be that women live longer because they develop healthier habits than menfor example, smoking and drinking less and choosing a better diet. But the number of women who smoke is growing and plenty of others drink and eat unhealthy foods. In any case, if women are so healthy, why is it that despite their longer lives, women spend more years of old age in poor health than men do? The lifestyle argument therefore does not answer the question either. As an experimental gerontologist, I approach this issue from a wider biological perspective, by looking at other animals. It turns out that the

females of most species live longer than the males. This phenomenon suggests that the explanation for the difference within humans might lie deep in our biology. Many scientists believe that the aging process is caused by the gradual buildup of a huge number of individually tiny faultssome damage to a DNA strand here, a deranged protein molecule there, and so on. This degenerative buildup means that the length of our lives is regulated by the balance between how fast new damage strikes our cells and how efficiently this damage is corrected. The bodys mechanisms to maintain and repair our cells are wonderfully effectivewhich is why we live as long as we do but these mechanisms are not perfect. Some of the damage passes unrepaired and accumulates as the days, months and years pass by. We age because our bodies keep making mistakes. We might well ask why our bodies do not repair themselves better. Actually we probably could fix damage better than we do already. In theory at least, we might even do it well enough to live forever. The reason we do not, I believe, is because it would have cost more energy than it was worth when our aging process evolved long ago, when our hunter-gatherer ancestors faced a constant struggle against hunger. Under the pressure of natural selection to make the best use of scarce energy supplies, our species gave higher priority to growing and reproducing than to living forever. Our genes treated the body as a short-term vehicle, to be maintained well enough to grow and reproduce, but not worth a greater investment in durability when the chance of dying an accidental death was so great. In other words, genes are immortal, but the bodywhat the Greeks called somais disposable.

It is well known that women live longer than men throughout the entire world. Some reasons deal with how a womans heart can be more active during some common conditions. These are all reasons that deal with a persons biological age and can show some great differences in biological aging between men and women. One of the most common reasons as towhy women live longer than men is because of how a womans heart can become more active. A major part of onesbiological age is that of ones heart activity in that when the heart is more active and healthier a persons biological age can be reduced because of how the heart is still working in a proper way. A womans heart tends to be more active primarily because of how the menstruation process causes the heart to exercise and to work at a greater level. What happens in menstruation that causes a womans heart to become active is that the estradiol hormone is released in the womans body during the process. Estradiol will work to give the womans heart a greater amount of energy because this is an especially powerful form of estrogen that can cause her heart to be more active. It is more powerful than other types of estrogen that can be found in a womans body. Because of the workout that is given to the heart during the menstruation period the heart will be able to work at a better rate and as a result to help with getting ones biological age reduced.

Another factor on why women live longer than men deals with the hormones that are produced in a womans body. Estrogen works differently than the testosterone that

is produced in a mans body. Testosterone can cause a man to engage in some more aggressive types of behavior that can be especially risky over time. Also, testosterone can increase LDL cholesterol levels in a mans body. Estrogen does not have as much of a cholesterol risk at testosterone does. Some reports even suggest that estrogen can help to increase HDL cholesterol levels in a womans body. HDL cholesterol is considered to be good cholesterol and can be very helpful with improving ones biological age. Of course general behaviors that women partake in that can impact ones biological age can be a major factor as well. Men are generally found to be more likely to smoke or drink alcohol than women. These activities are ones that are going to

increase ones biological age over time. The fact that women do not develop especially risky behaviors through estrogen production like men do with testosterone production is another factor to consider. These are all good reasons to consider as to why women live longer than men. These reasons deal with factors like the increased heart activity that a woman experiences during menstruation or how estrogen does not create higher LDL cholesterol levels in a womans body. All of these are factors that impact thebiological ages of men and women. In conclusion it's worth to mention that it is recommended to monitor your biological age for both men and women. Monitoring biological age with such tools as Health Reviser's Biological Age test will help to optimize anti-ageing programs, improve health, reveal hidden health issues early.

Across the industrialized world, women still live 5 to 10 years longer than men. Among people over 100 years old, 85% are women, according to Tom Perls, founder of the New England Centenarian Study at Boston University and creator of the website LivingTo100.com. Time.com asks him why. Q: Why do women live longer than men? A: One important reason is the big delay and advantage women have over men in terms of cardiovascular disease, like heart attack and stroke. Women develop these problems usually in their 70s and 80s, about 10 years later than men, who develop them in their 50s and 60s. For a long time, doctors thought the difference was due to estrogen. But studies have shown that this may not be the case, and now we know thatgiving estrogen to women post-menopause can actually be bad for them. One reason for that delay in onset of cardiovascular disease could be that women are relatively irondeficient compared to men especially younger women, those in their late teens and early 20s because of menstruation. Iron plays a very important part in the reactions in our cells that produce damaging free radicals, which glom onto cell membranes and DNA, and may translate into aging the cell. In fact, in our diets, red meat is the main source of iron, and lack of iron is probably one major reason that being vegetarian is healthy for you. There was a very good study looking at the intake of red meat and heart disease in Leiden in the Netherlands: in regions where people didn't eat red meat, those populations had half the rate of heart attack and stroke compared to the populations that did eat red meat. Another more complicated possibility [for women's longevity] is that women have two X chromosomes, while men have one. (Men have an X and a Y.) When cells go through aging and damage, they have a choice in terms of genes either on one X chromosome or the other. Consider it this way: you have a population of cells, all aging together. In some cells, the genes on one X chromosome are active; in other cells, by chance, the same set of genes, with different variations, are active on the other X chromosome. Don't forget, we all have the same genes the reason we differ is because we express different variations of those genes, like different colors of a car. Now, if one set of variations provides a survival advantage for the cells versus another, then the cells with the advantage will persist while the other ones will die off, leaving behind more cells with the genes on the more advantageous X chromosome. So, in women, cells can perhaps be protected by a slightly better variation of a gene on the second X chromosome. Men don't have this luxury and don't get this choice. It's very unclear [how big an effect that could have]. I've seen men who have done horrendous damage to themselves over time with smoking and drinking and who still get to 100 and older though that's very, very rare. They might have the right combination of some really special genetic variations that we call "longevity enabling genes" which we're on the mad hunt for. Meanwhile other individuals may do everything right and only make it into their 80s. That may be because they have what we call "disease genes," some genetic variations that are relatively bad for them. Now some of these [disease genes] may be on the X chromosome, [meaning that women who have the second X chromosome with which to compensate, would have an advantage]. But it's really still a very complicated puzzle to tease out. [There are a few other reasons that men die earlier in life more often than women.] Men in their late teens and 20s go through something called "testosterone storm." The levels of the hormone can be quite high and changeable, and that can induce some pretty dangerous behavior among young men. They don't wear their seatbelts; they drink too much alcohol; they can be aggressive with weapons and so on and so forth. These behaviors lead to a higher death rate. Another area where we see higher death rates among men is among the depressed especially older men. If they attempt suicide, they are more likely to succeed than women. Overall, about 70% of the variation around average life expectancy [just over 80 for women and just over 75 for men in the U.S.] is probably attributable to environmental factors your behaviors and your exposures. Probably only 30% is due to genetics. And that's very, very good news. There's so much we can do. Most of us should be able to get into our late 80s. What's more, to get to older ages, like the centenarians, you are necessarily compressing the time you're sick to the end of your life. It's not a case where the older you get, the sicker you get. It's very much the case that the older you get, the healthier you've been. But, in general, there are maybe three things men do worse than women. They smoke a lot more. (That gender gap is fortunately shrinking, since men are smoking less and less.) They eat more food that leads to high cholesterol. And, perhaps related to that, men tend not to deal with their stress as well as women. They may be more prone to internalizing that stress rather than letting go though that's a fairly controversial point. Nonetheless, stress plays a very important role in cardiovascular disease.

Why Women Live Longer than Men Women around the world have a survival advantage over men--sometimes by as much as 10 years. What gives them the upper hand? by Thomas T. Perls, M.D., M.P.H Harvard Medical School Ruth C. Fretts, M.D., M.P.H. Harvard Medical School

It is a fact of life that men enjoy certain physical advantages over women. On average, men are stronger, taller, faster and less likely to be overweight. But none of these attributes seem to matter over the long haul. For whatever the physical virtues of maleness, longevity is not among them. Women, as a group, live longer than men. In all developed countries and most undeveloped ones, women outlive men, sometimes by a margin of as much as 10 years. In the U.S., life expectancy at birth is about 79 years for women and about 72 years for men. The gender discrepancy is most pronounced in the very old: amongcentenarians worldwide, women outnumber men nine to one. The gender gap has widened in this century as gains in female life expectancy have exceeded those for males. The death rates for women are lower than those for men at all ages-even before birth. Although boys start life with some numerical leverage--about 115 males are conceived for every 100 females--their numbers are preferentially whittled down thereafter. Just 104 boys are born for every 100 girls because of the disproportionate rate of spontaneous abortions, stillbirths and miscarriages of male fetuses. More boys than girls die in infancy. And during each subsequent

year of life, mortality rates for males exceed those for females, so that by age 25 women are in the majority. For us, these statistics raise two questions: Why do men die so young? And why do women die so old? From the outset we would like to admit that we have no definitive answers to these questions. But the available evidence implicates behavioral as well as biological differences between the sexes, differences in the effects of medical technology, as well as social and psychological factors. Ultimately, our investigation of the gender gap in life span has led us to posit an evolutionary explanation, one that suggests that female longevity is more essential, from a Darwinian perspective, than the prolonged survival of males. The good news is that in spite of this evolutionary imperative, the gap between male and female life expectancy may now be narrowing. The bad news is that some of this convergence may be the result of women suffering more from what used to be considered "male" diseases. Toxic Testosterone Comparison of the death rates for men and women in the U.S. at various ages reveals gender differences in mortality patterns. Although death rates are higher for males than females at all ages, the difference between the sexes is more pronounced at certain stages of life. Between 15 and 24 years, for example, the male-tofemale mortality ratio peaks because of a sudden surge in male deaths with the onset of puberty. During this period, men are three times more likely to die than women, and most of the male fatalities are caused by reckless behavior or violence. Motor vehicle accidents are the most common cause of death for males in this age group, followed by homicide, suicide, cancer and drowning. Interestingly, a surge in male mortality has been observed in other primates at a similar stage in life: in young adult male macaques, for example, rates of death and "disappearance" are high compared with those of female macaques. The difference between male and female mortality declines until late middle age, when the mortality ratio plateaus. In the 55- to 64-yearold age group, behavior-related fatalities are still among the most common causes of death for men and are still much higher in men than in women. Men of this age are more than twice as likely as women to die in car accidents, for example, and almost four times as likely to take their own lives. Illnesses related to smoking and alcohol consumption also kill more

men than women in this age group. But heart disease is the main cause of the gender gap here. Men experience an exponential rise in the risk of heart disease beginning in their 40s; in contrast, women's risk of dying from heart disease does not begin to increase until after menopause, and it approaches the male risk only in extreme old age. Although the gender gap in this age group is smaller than the one described for young adults, the number of people affected by it is far greater. Whereas accidents claim the lives of 45 of every 100,000 young adult males annually, heart disease--the leading cause of death in men and women alike--kills 500 of every 100,000 men between the ages of 55 and 64 every year. Experts suspect that gender differences in mortality patterns may be influenced at least in part by sex hormones, namely the male hormone testosterone and the female hormone estrogen. The conspicuous peak in the sex-mortality ratio at puberty, for example, coincides with increased testosterone production in men. Because the male hormone has been linked with aggression and competitiveness as well as libido, some researchers ascribe this spike in male mortality to "testosterone toxicity." Later in life, testosterone puts men at risk biologically as well as behaviorally. It increases blood levels of the bad cholesterol (known as LDL, for lowdensity lipoprotein) and decreases levels of the good one (HDL, for high-density lipoprotein), putting men at greater risk of heart disease and stroke. Estrogen, on the other hand, has beneficial effects on cardiovascular health, lowering LDL cholesterol and increasing HDL cholesterol. A recent study at the University of Washington suggests that estrogen may exert these effects by regulating the activity of liver enzymes involved in cholesterol metabolism. Estrogen is also an antioxidant--that is, it neutralizes certain naturally occurring, highly reactive chemicals, called oxygen radicals, that have been implicated in neural and vascular damage and aging. Emerging evidence suggests that treatment with estrogen after menopause reduces a woman's risk of dying from heart disease and stroke, as well as her risk of dying in general. Estrogen therapy has also been shown in some studies to delay the onset of Alzheimer's disease. It is important to note that with the exception of this evidence regarding estrogen therapy, the relation between sex hormones and mortality patterns is still speculative. Furthermore, any attempt to

explain mortality patterns must include the recognition that these trends are relatively recent. As the graph shows, the two divergences we have been discussing did not emerge until the middle of the century. Before that time, the sex-mortality ratio was constant across age groups for which data are available. The recent changes can probably be accounted for by two societal factors: improvements in obstetrical care, which have dramatically reduced women's risks of dying in childbirth, and an increased availability of guns and cars, which has contributed to more accidental and violent deaths in young males. Historical Advantage Although the reasons women live longer than men may change with time, it seems likely that women have been outliving men for centuries and perhaps longer. Even with the sizable risk conferred by childbirth, women lived longer than men in 1900, and it appears that women have out survived men at least since the 1500s, when the first reliable mortality data were kept. Sweden was the first country to collect data on death rates nationally; in that country's earliest records, between 1751 and 1790, the average life expectancy at birth was 36.6 years for women and 33.7 years for men. Death rates in less developed countries, whose citizens have limited access to cars, guns and maternal care, also provide a measure of mortality before modernity. At present, the only countries in which male life expectancy exceeds that for females are those with longstanding sexual discrimination--including Bangladesh, India and Pakistan--where social pressures and practices such as female infanticide and bride-burning result in unique "losses" of females. The fact that women live longer than men does not, however, mean that they necessarily enjoy better health. It could be that women live with their diseases, while men die from them. Indeed, there is a difference between the sexes in disease patterns, with women having more chronic nonfatal conditions--such as arthritis, osteoporosis and autoimmune disorders--and men having more fatal conditions, such as heart disease and cancer. {Here was one of the two graph referred to in the article, unfortunately it was not in gif or jpeg format. It showed that as of 1970 the gap between men an woman increased}

Survival of the Fittest To understand better the forces that control human aging and longevity, we have tried to determine whether the longer life span of females might be part of some grand Darwinian scheme. Gender differences in longevity have been observed in other members of the animal kingdom: in fact, in almost all species that have been observed in the wild, females tend to live longer than males. Female macaques live an average of eight years longer than males, for example, and female sperm whales outlive their male counterparts by an average of 30 years. It seems that a species' life span is roughly correlated with the length of time that its young remain dependent on adults. We have come to believe that when a significant, long-term investment of energy is required to ensure the survival of offspring, evolution favors longevity--in particular, female longevity. Indeed, we believe that the necessity for female longevity in the human reproductive cycle has determined the length of the human life span. We start with the assumption that the longer a woman lives and the more slowly she ages, the more offspring she can produce and rear to adulthood. Long-lived women therefore have a selective advantage over women who die young. Long-lived men would also have an evolutionary advantage over their shorter-lived peers. But primate studies suggest that men's reproductive capacity is actually limited more by their access to females than by life span. Hence, the advantage of longevity for men would not be nearly as significant as it is for women. And because males historically are not as involved in child care as females, in the not so distant evolutionary past the survival of a man's offspring depended not so much on how long he lived as on how long the children's mother lived. One might think that the existence of menopause halts the transmission of a woman's genes and thus contravenes the evolutionary argument for female longevity. We think just the opposite: menopause confers a selective advantage and promotes longer life by protecting females from the increased mortality risk associated with childbirth at advanced age. Even today thisincrease in risk is considerable: a woman in her 40s is four to five times more likely to die in childbirth than a 20-year-old. When menopause evolved, maternal mortality would have been much greater. If offspring require a significant maternal investment of time and energy to survive--which human children most certainly do--then

there probably comes a point in a woman's life when it is more efficient to pass on her genes by caring for the children and grandchildren she already has than by producing and nurturing more children, risking death and the death of her existing children in the bargain. The argument that menopause is an evolutionary adaptation was first developed in 1957 by George C. Williams, now at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and recent anthropological studies have supported it. Because human children are dependent for such a long time, continued health and longevity may enhance older women's contribution to the gene pool even when they can no longer reproduce. In our own studies of centenarians, we have found that a surprising proportion of women who lived to be 100 or more gave birth in their 40s. One of our subjects had even had a child at the age of 53. We found that, overall, 100-year-old women were four times as likely to have given birth in their 40s as a control group of women, born in the same year, who died at the age of 73. This observation reinforces our suspicion that longevity is linked with fecundity at an advanced age. Of course, we do not mean that having a baby in middle age makes a woman live longer. Rather, it seems that the factors that allow certain older women naturally to conceive and bear children--a slow rate of aging and perhaps also a decreased susceptibility to the diseases associated with aging--also improve these women's chances of living a long time. We propose that women's longevity edge over men may simply be a by-product of genetic forces that maximized the length of time during which women could bear and raise children and perhaps assist with grandchildren as well. Moreover, male longevity may simply be a function of the fact that men must carry the genes that ensure longevity to pass them on to their daughters. Thus, the necessity of female longevity in the human species may be the force that has determined the natural life span for both men and women. The Secret to Living Longer If female longevity is the product of evolutionary forces, then one might wonder what physiological mechanisms have evolved to support the preferential survival of women over men. As we have mentioned, sex hormones are thought to be important factors in determining the relative susceptibilities of the genders to aging and disease. Less obvious is the contribution that menstruation might make to longevity. Because of the monthly shedding of the uterine

lining, premenopausal women typically have 20 percent less blood in their bodies than men and a correspondingly lower iron load. Because iron ions are essential for the formation of oxygen radicals, a lower iron load could lead to a lower rate of aging, cardiovascular disease and other age-related diseases in which oxygen radicals play a role. Indirect support for this theory comes from studies at the University of Kuopio in Finland and the University of Minnesota Medical School. In these studies, male volunteers who made frequent blood donations had less oxidation of LDL cholesterol--a key step in the development of atherosclerosis and heart disease. Women also have a slower metabolism than men--a distinction that makes them more prone to obesity. But there may also be an inverse relation between metabolic rate and life span. Evidence of this link comes from animal studies of food restriction, which slows metabolic processes: in experiments sponsored by the National Institute on Aging, monkeys that ate 30 percent less of the same diet as their free-feeding peers seemed to age more slowly. Studies of so-called clock genes in microscopic worms have also demonstrated the connection between metabolic rate and life span. Siegfried Hekimi of McGill University has observed that worms with particular mutations in these genes live five times as long as normal animals and have much slower physiological functions. Although it is still not known why men's metabolism rates are faster than women's, it is becoming clear that this difference is present almost from the moment of conception, when male embryos divide faster than female ones. The faster metabolic rate may make men's cells more vulnerable to breakdown, or it may simply mean that the male life cycle is completed more promptly than the female one. Finally, chromosomal differences between men and women may also affect their mortality rates. The sex-determining chromosomescan carry genetic mutations that cause a number of life-threatening diseases, including muscular dystrophy and hemophilia. Because women have two X chromosomes, a female with an abnormal gene on one of her X chromosomes can use the normal gene on the other and thereby avoid the expression of disease (although she is still a carrier of the defect). Men, in contrast, have one X chromosome and one Y chromosome, and so they cannot rely on an alternative chromosome if a gene on one of the sex chromosomes is defective. This disadvantage became more ominous when, in 1985, researchers at Stanford University reported the discovery on the X chromosome

of a gene critical to DNA repair. If a man has a defect in this gene, his body's ability to repair the mutations that arise during cell division could be severely compromised. The accumulation of such mutations is thought to contribute to aging and disease. There is also increasing interest in women's second X chromosome as a longevity factor in and of itself. Although one of the two Xs is randomly inactivated early in life, the second X seems to become more active with increasing age. It may be that genes on the second X "kick in" and compensate for genes on the first X that have been lost or damaged with age. This compensation could have a sizable influence, as it appears that roughly 5 percent of the human genome may reside on the X chromosome. In recent years the X chromosome has also become the focus of the search for genes that might directly determine human life span. {The second graph would go here it shows the gradual increase in % of women as they age.}

Closing the Gender Gap Men and women alike have seen profound gains in life expectancy in this century. Since 1900, the average national increase in life expectancy in developed countries has been 71 percent for women and 66 percent for men. This increase cannot be explained by physiological or evolutionary theories. Rather, swift changes in knowledge of health and disease, changes in lifestyle and behavior, and advances in medical technology have greatly improved the chances of both sexes' living to old age. In the past two decades, however, there has been a notable deceleration in the extension of life expectancy in women. The reasons for this decline are still being debated. Some researchers feel that women in developed countries are close to reaching the natural limits of human life span, and so their gains in life expectancy must inevitably diminish. But some sociologists have discounted this reasoning, pointing instead to women's changing roles in society. As more women have taken on behaviors and stresses that were formerly confined to men-smoking, drinking and working outside the home--they have become more likely to suffer from diseases that were traditionally considered "masculine." Mortality from lung cancer, for example, has almost

tripled in women in the past two decades. Smoking seems to be the "great equalizer" for men and women: current actuarial data from Bragg Associates in Atlanta show that on average middle-aged female smokers live no longer than male smokers do. In part because of these factors, men's and women's death rates in the U.S. have begun to converge in the past 20 years. But it is primarily the reduction in male mortality, as opposed to the increase in female mortality, that is narrowing this gender gap. In general, the higher a nation's level of social and economic development, the greater the life expectancy for both men and women and the greater the convergence in the two figures. Research on sex hormones, sex chromosomes and gender-specific behavior is sure to further understanding of the human body well beyond the questions posed by the longevity gender gap. In exploring this intriguing phenomenon, investigators will undoubtedly find clues to how both men and women can live longer and more healthy lives.

Current data 5 shows that the mean starting age for smoking in males is 15.3 years vs. 17.2 years in females. On average men smoke more cigarettes per week than women, except in the youngest and oldest age groups. In many cultural groups, smoking by women is still relatively rare, but is an accepted part of being male. For instance, studies 2 have shown smoking prevalence in: Vietnamese men 37% vs.

women 4%; Chinese men 26% vs. women2%; Greek men 31% vs. women 10% and Italian men 28% vs. women 18%.

Illness and death caused by smoking In 2003, 14.8% of male deaths and 8.4% of female deaths were due to tobacco related disease- the largest attributable risk factor to the burden of disease in Australia. 4

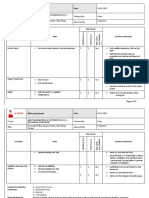

Age 0-14 15-34 35-64 M/FM/FM/F M/F

65+

Cancer 0 / 0 0 / 0 1375/454 4207/1506 Heart Disease 0 / 0 27/7 1114/225 1707/954 COPD 0 / 0 0 / 0 229/130 2275/1205 1565/1285

Other 43/33 27/19 326/179 ETS 14 / 9 0 / 0 2 / 8 32/63

Deaths attributable to Tobacco, 1998 by age, sex 3 Sex differences largely reflect patterns of smoking 25 years ago.

Men are more than twice as likely to die in a car crash as women, consider the

yearly statistics shown below. In fact, studies have shown as many as 73 percent of all people killed in car accidents are male. Since record keeping began: male fatalities significantly outweigh female fatalities. However men and women do not drive the same number of miles under the same conditions- men do about 60-65% more driving than women. Studies show that woman take shorter trips and female drivers have a greater number of minor crashes than do men. However men are still 70% more likely to be in a serious crash. Insurance company AAMI has found some interesting statistics in a recent telephone survey of more than 2,000 drivers. - 55 per cent of men 30 per cent of women drink drive. - 47 per cent of men 38 per cent of women have rudely gestured at other drivers. - 84 per cent of men 77 per cent of women have crashed their vehicle, - 51 per cent of men 40 per cent of women have been distracted by billboards while driving - 46 per cent of men 36 per cent of woman admitted to verbally abusing another driver. - 22 per cent of men 15 per cent of women admitted to using their mobile phones without hands-free accessories while driving. So you can see from the survey that things are not looking that great for men, but do all those statistics make women better drivers? Our claims data shows that mens crashes tend to be more serious than womens, they are more likely to be involved in head-on collisions, roll-overs and loss-of-control crashes, as well as crashes involving pedestrians, cyclists and animals. AAMI spokesman Geoff Hughes said. Violations for which men scored at least 50 percent higher than women: TYPE OF VIOLATION RATIO M:F

Reckless driving 3.41 DUI 3.09 Seatbelt violations 3.08 Speeding 1.75 Failure to yield 1.54 Stop sign/signal violation 1.53 Some researchers believe the explanation is to be found hormones related to aggessiveness, others put more emphasis on data such as the measurebly greater alcohol use among men while driving. So Are Women Better Drivers Than Men? Many auto insurance industry experts would agree with the theory that men, especially young men, tend to drive more aggressively than women and display their aggression in a direct manner, rather than indirectly. Furthermore, as a rule of thumb, male drivers are more likely than women to break the law, and the male of the species tends to be more of a risk-taker.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Health Checkup: How To Live 100 YearsDocument8 pagesHealth Checkup: How To Live 100 YearsMutante TrioPas encore d'évaluation

- Living To 100Document4 pagesLiving To 100marginalmePas encore d'évaluation

- Mock 1Document10 pagesMock 1Bunyodbek AkbarovPas encore d'évaluation

- Borrowed Time: The Science of How and Why We AgeD'EverandBorrowed Time: The Science of How and Why We AgeÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (5)

- What Is The Secret of A Long LifeDocument4 pagesWhat Is The Secret of A Long LifetipuazazPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Games - Differences of Men and Women GameDocument52 pages3 Games - Differences of Men and Women Gamejenny alla olayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Weird Facts About Being Tall or ShortDocument4 pagesWeird Facts About Being Tall or ShortjohntandraPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is The Prostate?: New StudyDocument4 pagesWhat Is The Prostate?: New StudykimwinwinPas encore d'évaluation

- Hsoc 275 - Final Exam ReviewDocument3 pagesHsoc 275 - Final Exam ReviewRyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Sex Ratio Trends ExplainedDocument2 pagesSex Ratio Trends ExplainedNguyen LinhPas encore d'évaluation

- Ten Politically Incorrect Truths About Human NatureDocument7 pagesTen Politically Incorrect Truths About Human NaturePreda MarianPas encore d'évaluation

- The Better Half: On the Genetic Superiority of WomenD'EverandThe Better Half: On the Genetic Superiority of WomenÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (1)

- HSA 535 Cohort Follow-up Studies CVD African American WomenDocument8 pagesHSA 535 Cohort Follow-up Studies CVD African American Womentswag2014Pas encore d'évaluation

- English DebateDocument3 pagesEnglish DebatememadysPas encore d'évaluation

- Women and Dementia A Marginalised Majority1Document16 pagesWomen and Dementia A Marginalised Majority1Michelle HoranPas encore d'évaluation

- Premature Death RatesDocument2 pagesPremature Death Ratesmdavila1705Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2013 Regan Dan PartridgeDocument13 pages2013 Regan Dan PartridgeOkae SayaPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Senate: Testimony T.S. Wiley Special Committee On AgingDocument43 pagesUnited States Senate: Testimony T.S. Wiley Special Committee On AgingWileyProtocolPas encore d'évaluation

- Passionate Legalities of MarriageDocument40 pagesPassionate Legalities of MarriageTipu Salman MakhdoomPas encore d'évaluation

- Risks Associated With Pediatric NeuterDocument12 pagesRisks Associated With Pediatric NeuterfennarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Risks Associated With Pediatric NeuterDocument12 pagesRisks Associated With Pediatric NeuterfennarioPas encore d'évaluation

- ThomasDocument12 pagesThomasLê Thu AnPas encore d'évaluation

- A Long and Healthy LifeDocument1 pageA Long and Healthy LifeRaysbel GimenezPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Women Are The Superior Gender: in A Battle of The Sexes, Bet On The WomenDocument3 pagesWhy Women Are The Superior Gender: in A Battle of The Sexes, Bet On The WomenCwithePas encore d'évaluation

- SADPERSONS SuicideriskDocument2 pagesSADPERSONS SuicideriskCandace RobertsPas encore d'évaluation

- WritingfinalpaperDocument8 pagesWritingfinalpaperapi-279487928Pas encore d'évaluation

- 317-Article Text-3768-3-10-20190822 PDFDocument10 pages317-Article Text-3768-3-10-20190822 PDFCIR EditorPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding the Multifaceted Process of AgeingDocument13 pagesUnderstanding the Multifaceted Process of AgeingSyazmin KhairuddinPas encore d'évaluation

- Amazing Facts About Twins: Day in HealthDocument3 pagesAmazing Facts About Twins: Day in HealthjohntandraPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading and Discussion Fall 2011 BZM C3Document12 pagesReading and Discussion Fall 2011 BZM C3Bezmialem Prep DırectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Mechanisms of AgingDocument139 pagesMechanisms of AgingDavaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 4Document20 pagesChapter 4Christine Kimberly ObenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Research PaperDocument10 pagesResearch Paperapi-710544292Pas encore d'évaluation

- Topic 5 - Handbook of Medical Sociology Ch4 - 2Document23 pagesTopic 5 - Handbook of Medical Sociology Ch4 - 2AngellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Modern Feminism: Warren Farrell On Institutionalized Misandry and Additional OpinionsDocument7 pagesModern Feminism: Warren Farrell On Institutionalized Misandry and Additional OpinionstheprofilePas encore d'évaluation

- Life Expectancy and Its Role in Measuring Health DisparitiesDocument6 pagesLife Expectancy and Its Role in Measuring Health DisparitiesAlejandro MendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Men's Lives Are Shorter Than Women's?: The Adventure Streak and Adrenalin RushDocument2 pagesWhy Men's Lives Are Shorter Than Women's?: The Adventure Streak and Adrenalin RushFelicia FeliciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Part B-24-All Life Is Connected - Q&ADocument6 pagesPart B-24-All Life Is Connected - Q&Afernanda1rondelliPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary of How Not to Age by Michael Greger M.D. FACLM: The Scientific Approach to Getting Healthier as You Get OlderD'EverandSummary of How Not to Age by Michael Greger M.D. FACLM: The Scientific Approach to Getting Healthier as You Get OlderÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- Abortion PDFDocument4 pagesAbortion PDFJESSMAR GRACE PARMOSAPas encore d'évaluation

- Alzheimer's Disease: a Growing Health Care Issue Among the ElderlyD'EverandAlzheimer's Disease: a Growing Health Care Issue Among the ElderlyPas encore d'évaluation

- Pre-Intermediate/Intermediate Reading Text: LongevityDocument2 pagesPre-Intermediate/Intermediate Reading Text: LongevityMaria Vitória Carvalho100% (1)

- Aging Quiz 2 AnswersDocument5 pagesAging Quiz 2 AnswersdindandinigaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hormones made transgender journey safer than surgeryDocument2 pagesHormones made transgender journey safer than surgeryForam BhedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Argumentative EssayDocument6 pagesArgumentative EssayKevin M. GreciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Transgeder - Analytical Exposition - Maharani Bening Khatulistiwa XI IIS 1Document2 pagesTransgeder - Analytical Exposition - Maharani Bening Khatulistiwa XI IIS 1reksi alimPas encore d'évaluation

- The Five Sexes: Beyond Male and FemaleDocument13 pagesThe Five Sexes: Beyond Male and FemalePNirmalPas encore d'évaluation

- Age Disparity Between GendersDocument22 pagesAge Disparity Between Gendersapi-659623153Pas encore d'évaluation

- 110 Interesting Weird and Surprising Sex FactsDocument10 pages110 Interesting Weird and Surprising Sex Factsglendalough_man100% (1)

- AgingDocument8 pagesAgingBeata PieńkowskaPas encore d'évaluation

- SexDocument4 pagesSexQuotes&Anecdotes100% (1)

- Longevity - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument11 pagesLongevity - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaJames DriscollPas encore d'évaluation

- Fertility Rules: The Definitive Guide to Male and Female Reproductive HealthD'EverandFertility Rules: The Definitive Guide to Male and Female Reproductive HealthPas encore d'évaluation

- Chrisler 2016Document19 pagesChrisler 2016Uzi SuruziPas encore d'évaluation

- My PDF jnL2lI PDFDocument2 pagesMy PDF jnL2lI PDFCarmen ConcaPas encore d'évaluation

- Unintentional Suicide: A Doctor's Guide to Preventing DiseaseD'EverandUnintentional Suicide: A Doctor's Guide to Preventing DiseaseÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Kidney Problems Research GuideDocument4 pagesKidney Problems Research GuideKim GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Inverted Uterus GuidelinesDocument2 pagesInverted Uterus GuidelinesEndang Sri WidiyantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Nursing responsibilities for Tocilizumab administrationDocument2 pagesNursing responsibilities for Tocilizumab administrationMiguel Paolo Bastillo MercadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Healthand Safety Situationsof Garments Workersin Developing Countries AStudyon BangladeshDocument13 pagesHealthand Safety Situationsof Garments Workersin Developing Countries AStudyon BangladeshA FCPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Conference Report on Gynecology CasesDocument44 pagesClinical Conference Report on Gynecology CasesPritta23Pas encore d'évaluation

- Wellness Tourism Sector Strategy - National Export Strategy (2018-2022)Document55 pagesWellness Tourism Sector Strategy - National Export Strategy (2018-2022)Ministry of Development Strategies and International TradePas encore d'évaluation

- Medication Safety in LactationDocument30 pagesMedication Safety in Lactationhalima alzadjaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer Behavior - Value Transfusion ModelDocument2 pagesConsumer Behavior - Value Transfusion ModelaminajavedPas encore d'évaluation

- LPL - PSC Ashok Vihar H-62, Lig Flats, Phase-1, Ashok Vihar 9555828281 DelhiDocument1 pageLPL - PSC Ashok Vihar H-62, Lig Flats, Phase-1, Ashok Vihar 9555828281 DelhiRahul GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Complete 5-Ingredient Mediterranean Diet Cookbook - Easy and Healthy Mediterranean Diet Recipes For Your Weight Loss, Heart and Brain Health and Diabetes Prevention PDFDocument121 pagesThe Complete 5-Ingredient Mediterranean Diet Cookbook - Easy and Healthy Mediterranean Diet Recipes For Your Weight Loss, Heart and Brain Health and Diabetes Prevention PDFsavica pricop100% (8)

- Pharmacology: Pharmacokinetics - Part 1Document9 pagesPharmacology: Pharmacokinetics - Part 1RodrigoPas encore d'évaluation

- DT-3000 SDS 090115Document8 pagesDT-3000 SDS 090115Alejandro VescovoPas encore d'évaluation

- District Health & Family Welfare Samiti U Tar Dinajpur: Corr 04i! 1& 31Document10 pagesDistrict Health & Family Welfare Samiti U Tar Dinajpur: Corr 04i! 1& 31TopRankersPas encore d'évaluation

- There Are Seven Key Elements of and Occupational Health and Safety Management System PolicyDocument18 pagesThere Are Seven Key Elements of and Occupational Health and Safety Management System PolicyHSE Health Safety EnvironmentPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3a Online ActivityDocument1 pageChapter 3a Online ActivityIrfan HarrazPas encore d'évaluation

- Cirrus Health Presentation 0108dDocument10 pagesCirrus Health Presentation 0108dsureshnc23Pas encore d'évaluation

- SAMPLE 2 - Writing An ArticleDocument2 pagesSAMPLE 2 - Writing An ArticleMiz MalinzPas encore d'évaluation

- Managing dental patients with cardiovascular diseasesDocument54 pagesManaging dental patients with cardiovascular diseasesSafiraMaulidaPas encore d'évaluation

- MAPEH 2 Lessons on Music, Art & PE for 3rd QuarterDocument8 pagesMAPEH 2 Lessons on Music, Art & PE for 3rd QuarterERWIN MEONADAPas encore d'évaluation

- Herbal Formularies For Health Professionals, Volume 3: Endocrinology, Including The Adrenal and Thyroid Systems, Metabolic Endocrinology, and The Reproductive Systems - Dr. Jill StansburyDocument5 pagesHerbal Formularies For Health Professionals, Volume 3: Endocrinology, Including The Adrenal and Thyroid Systems, Metabolic Endocrinology, and The Reproductive Systems - Dr. Jill Stansburyjozutiso17% (6)

- The Cost of CareDocument3 pagesThe Cost of CareSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticePas encore d'évaluation

- Risk Assessment - AbbDocument3 pagesRisk Assessment - AbbAbdul RaheemPas encore d'évaluation

- Drug EducationDocument5 pagesDrug EducationChristina Lafayette SesconPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessing Childbearing WomenDocument24 pagesAssessing Childbearing WomenCrestyl Faye R. CagatanPas encore d'évaluation

- Musculoskeletal Interventions Techniques For Therapeutic Exercises 3rd Ed .Document1 164 pagesMusculoskeletal Interventions Techniques For Therapeutic Exercises 3rd Ed .Gabriela82% (11)

- Kendhujhar Revised MSPLDocument58 pagesKendhujhar Revised MSPLRakesh MitraPas encore d'évaluation

- Sds333s00 Calfoam Es-303Document8 pagesSds333s00 Calfoam Es-303awsarafPas encore d'évaluation

- Factors Associated with ADHD Medication Prescription RatesDocument9 pagesFactors Associated with ADHD Medication Prescription RatesNancy Dalla DarsonoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pathology & Laboratory Design (FEUDocument17 pagesPathology & Laboratory Design (FEUMichaela Constantino100% (1)

- Tobacco Regulation ACT OF 2003Document13 pagesTobacco Regulation ACT OF 2003Sidnee MadlangbayanPas encore d'évaluation