Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Iran and The World A Foreign Policy Platform For Democracy

Transféré par

The Wilson CenterDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Iran and The World A Foreign Policy Platform For Democracy

Transféré par

The Wilson CenterDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

MIDDLE EAST PROGRAM OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES FALL 2011

FALL

2011

PROGRAM OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES

MIDDLE EAST

Iran and the World: A Foreign Policy Platform for Democracy

Roberto Toscano,

Foreign policy issues have definitely not appeared among the priorities, or the slogans, of the Green Movement.1 This is no surprise, since the focus of popular grievance against the Iranian regime has been its brazen denial of the rights of citizens as voters and subsequently the brutality of the repression against the ensuing mass protest. But there is another, less explicit but more substantial reason for the absence of foreign policy issues in the present discourse of democratic protesters and dissidents. The area of international relations can be easily presented by the regime as an area of national interest, allowing it to brand criticism as unpatriotic and as a way of weakening the nation against its enemies in general those who do not want to recognize the legitimate role and place of the great nation on the world scene. This explains why Green Movement leaders have so far basically shied away if not very occasionally and in a very ad hoc fashion from addressing foreign policy issues. It is comprehensible, but at the same time wrong and a sign of weakness, that, by default, they tacitly concede to the regime the hegemonic right to define national interest. Iranian citizens those who have adhered to the Green Movement and those who are still standing on the sidelines or still support the regime need to know more about what kind of foreign policy a post-regime democratic Iran would elaborate upon and put into practice. Iran has the need and the ambition to be a player in the international arena. This would be even more the case in a democratic Iran finally integrated in the global community, from which it has been isolated under the present regime. Besides, if properly handled,

President, Intercultura Foundation, Italy; former Public Policy Scholar, Woodrow Wilson Center; and former Italian Ambassador to Iran and India

MIDDLE EAST PROGRAM OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES FALL 2011

Director Dr. Haleh Esfandiari Assistants Kendra Heideman Mona Youssef Special thanks Special thanks to Kendra Heideman and Mona Youssef for coordinating this publication; Tara Dewan-Czarnecki, Rachel Peterson, and Laura Rostad of the Middle East Program for their editing assistance; the Design staff for designing the Occasional Paper Series; and David Hawxhurst for taking the photograph.

The Middle East Program was launched in February 1998 in light of increased U.S. engagement in the region and the profound changes sweeping across many Middle Eastern states. In addition to spotlighting day-to-day issues, the Program concentrates on long-term economic, social, and political developments, as well as relations with the United States. The Middle East Program draws on domestic and foreign regional experts for its meetings, conferences, and occasional papers. Conferences and meetings assess the policy implications of all aspects of developments within the region and individual states; the Middle Easts role in the international arena; American interests in the region; the threat of terrorism; arms proliferation; and strategic threats to and from the regional states. The Program pays special attention to the role of women, youth, civil society institutions, Islam, and democratic and autocratic tendencies. In addition, the Middle East Program hosts meetings on cultural issues, including contemporary art and literature in the region. Current Affairs: The Middle East Program emphasizes analysis of current issues and their implications for long-term developments in the region, including: the events surrounding the uprisings of 2011 in the Middle East and its effect on economic, political and social life in countries in the region, the increased use of social media, the role of youth, PalestinianIsraeli diplomacy, Irans political and nuclear ambitions, the drawdown of American troops in Afghanistan and Iraq and their effect on the region, human rights violations, globalization, economic and political partnerships, and U.S. foreign policy in the region. Gender Issues: The Middle East Program devotes considerable attention to the role of women in advancing civil society and to the attitudes of governments and the clerical community toward womens rights in the family and society at large. The Program examines employment patterns, education, legal rights, and political participation of women in the region. The Program also has a keen interest in exploring womens increasing roles in conflict prevention and post-conflict reconstruction activities. Islam, Democracy and Civil Society: The Middle East Program monitors the growing demand of people in the region for the transition to democratization, political participation, accountable government, the rule of law, and adherence by their governments to international conventions, human rights, and womens rights. It continues to examine the role of Islamic movements and the role of Islamic parties in shaping political and social developments and the variety of factors that favor or obstruct the expansion of civil society.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not reflect those of the Woodrow Wilson Center. This article is part of a longer piece written by the author during his stay at the Wilson Center.

foreign policy issues can be addressed in such a way as to widen the range of popular grievances against the regime. Iranian democrats should not behave as if foreign policy were an area of strength for the regime when actually it is an area of weakness. Finally, if the democratic movement wants to graduate from civil society protest to political alternative, it is indispensable for them to start working on the foreign policy plank of a political platform, looking for consensus or at least compromise on individual issues. The only way to challenge the pretense that the regime is the custodian of national interest and to debunk the myth of a foreign-directed and foreign-inspired democratic movement (a myth which still has some efficacy in certain segments of the population), is to de-construct this preposterous pretense, address it critically, and propose alternative policies. At the end of this process, it should also become clear to those who are suspicious or confused that the real patriots in Iran are the supporters of the Green Movement. The foreign policy of the present regime can be schematically represented both in terms of actual behavior and narrative in the form of three concentric circles.2 The first, the outermost, relates to the religious identity of the regime, Islamic and Shia; the second reflects an avowed antiimperialist identity; the third, the innermost, is comprised of national interest themes. The first and probably most important thing that has to be said is that as one moves outwards, the degree of popular consensus decreases, whereas the inner core of national-interest foreign policy issues reveals a high degree of consensus, in some cases nearing unanimity. The regime is clearly aware of this, and it is evident that many of its stands and declarations related to the first two circles religious and anti-imperialist are destined for external consumption rather than aimed at Iranian citizens. This is the case, for instance, of the Islamic dimension, primarily because after the universalist and expansionist dreams of the early stage of the Revolution, the leaders of the Islamic Regime gave up Trotskyite dreams of exporting the Revolution. They focused more realistically on the consolidation and the preservation of the regime, thus promoting, in Stalinist fashion, political Islam elsewhere only to the extent that it could contribute to the goal of consolidation and preservation of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The regime is fully aware that the vast majority of Iranians, including its own supporters, are not ready to risk their security or pay financially for the sake of ideologically common,

but substantially alien, causes. This is all the more so when they concern Arabs, with whom one must say Iranians have trouble recognizing any true affinity, in spite of the fact that they belong to the same Islamic community, the ummah. Regarding one concrete case, that of Hezbollah, we cannot avoid stressing that most Iranians react in an extremely negative way when they consider the flow of resources (their money!) that their regime devotes to supporting this Arab Shia movement. Hezbollah is for the Iranian regime more of the exception than the rule in terms of active Shia solidarity; it can be explained not by religious affinity but rather in terms of asymmetrical deterrence. Hezbollah is clearly cherished and supported as an asset that can be instrumental for the pursuit of Iranian goals and activated in case of an American or Israeli attack against Iran. In other cases, those that are not related to the regimes geopolitical or security interests, Shia solidarity is very generic and very cautious. The plight of Pakistani Shias, who are the object of frequent brutal attacks, does not excessively worry the Iranian regime, which is reluctant to engage in controversy and polemic with Pakistan. Likewise, Iran has been extremely cautious in relation to the repression of the Shia majority in Bahrain. The issue of Israel-Palestine is also a very interesting case in point. Although the plight of Palestinians raises feelings of solidarity among Iranians and leads them to condemn Israeli policies, the regime goes much beyond this. It has turned hostility toward Israel into a necessary component of its own political identity, as necessary, I would say, as antiU.S. hostility, which is even less shared by the population, and as widespread as another essential identity marker, the hejab. This exasperated, angrier-than-thou rhetoric against Israel straddling two circles of foreign policy, the religious and the anti-imperialist has moved away from the criticism of specific Israeli policies and actions, such as the settlements, to military action against Gaza or Lebanon. It has instead moved toward questioning the existence of the State of Israel and joining Ahmadinejad in finally crossing the dividing line between anti-Zionist and anti-Israeli sentiments and antiSemitism, as demonstrated by the infamous Holocaust denial conference held in Tehran in December 2006.3 If we were to pinpoint the place of anti-Semitism in the circular schema described above, I maintain that it would belong to the most marginal, most peripheral location, i.e. the area of most rarefied, weakest popular consensus. Holocaust denial was definitely a gimmick invented for external con-

MIDDLE EAST PROGRAM OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES FALL 2011

sumption, to prove that Iran, although it is Persian and not Arab, Shia and not Sunni, is second to none in hostility to the State of the Jews. As for the merely anti-imperialist dimension of Iranian foreign policy, it seems clear that the vast majority of Iranian citizens are well aware that being friendly with anti-imperialist regimes, such as Hugo Chavezs Venezuela, does not compensate, in terms of actual advantages for Irans security or economic interests, for the hostility and tension with the United States and Europe. The Green Movement should explicitly criticize both the Shia and the anti-imperialist dimensions of the foreign policy of the Iranian regime and propose a different way of addressing them that is less provocative, less costly, and more effective. The present turmoil in the Middle East and North Africa region offers a perfect opportunity to change foreign policy and to link up with the popular demand for democracy and human rights in many, if not most, Arab countries. While the present Iranian regime supports both extremist movements and dictatorial regimes Shia, Sunni, or even secular, as in the case of Syria a democratic Iran would focus on human rights as a guiding principle for support. It has to be added, incidentally, that solidarity with Assad is definitely not attributable to religious affinity with the vaguely Shia Alawis, but rather to geopolitical considerations. Human rights for Palestinians, including self-determination and the declaration of a Palestinian state; human and civil rights for the Shias in Bahrain, not insofar as Shia are supposedly pro-Iranian, but as a majority that has the right not to be oppressed; and so on. There is no contradiction between demanding human rights and a democratic system for yourself and for your country, and supporting human rights and democratic freedoms for others. The Green Movement should actually increase and amplify the support it has already expressed toward the Arab Spring,4 and take this occasion to transform into explicit and courageous policies the merely rhetorical and self-serving narrative of the regime, fraudulently presenting itself as a paladin of religion and the rights of peoples against imperialist subjugation and exploitation. Moreover, one should not forget that the contradictions, the political and economic costs, and the often merely rhetorical nature of regime policies in these two dimensions of foreign policy are also causes of disagreement and division within the regime itself. When Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei, President Ahmadinejads chief-of-staff, declared in 2008 friendship toward the Israeli people, he was certainly expressing a view that many Iranians do not consider outrageous, and certainly one that is inconsistent with the antiSemitic masquerade organized by his president and mentor. When Khatami expressed, as President, in 2004 the view that Iran is in favor of a united democratic Palestine including Arabs, Jews, and Christians, adding that it would accept any other solution that is freely accepted by Palestinians themselves (implicitly referring to the two-state solution), he was not speaking only as an individual but was expressing a view that is acceptable to most Iranians, including many within the present regime. Especially significant is the American question. Marg bar Amrika (i.e. Death to America) does not reflect the sentiments of most Iranians, both pro-regime and antiregime. Paradoxically, it is both true that the regime finds one of the essential elements of its identity in its reciprocated enmity toward the United States, and that whoever could bring about the recognition of the Islamic Republic by the United States would gain invaluable political status and popular credibility. Unlike the United Kingdom, which faces popular suspicion and aversion, fed by historical grievances and persistent (and often rather wild) conspiracy theories, the United States is considered phenomenological, not ontologically hostile, and only hostile in a more recent context i.e. since the 1953 anti-Mossadeq coup, which, incidentally, was promoted mainly by the British, whom the United States joined in an act of betrayal of its previous friendship with Iran. Many in the regime, with the exception of its most radical members, are not convinced that America is a permanent, necessary enemy. Great Satan is by now an outdated and out-fashioned epithet, and I believe that the dream of many in the regime is to be treated by the Americans in the same way that the Americans treat the Chinese regime: with respect and with no idea of regime change, despite political disapproval regarding lack of democracy and human rights violations. So far, I have mentioned the two dimensions of the regimes foreign policy that are relatively easy to criticize and easy to draft an alternative approach to. The rhetorical nature of regime policies and the fact that religious and anti-imperialist solidarity are easy to de-construct as rhetorical concoctions for external use make the regime especially vulnerable to criticism. The Green Movement should not have much trouble in explicitly addressing religion and anti-imperialism both for criticizing the regime and for the positive, program-

matic aspects of its own political mobilization. As we move, however, toward the innermost circle of the schema the one comprised of national interest issues things become more complicated. This area is characterized by a high degree of consensus, so it is much more difficult to criticize regime narratives and policies and to articulate alternative policies. Thus, Iranian democrats run the risk of appearing as substantially in agreement with the regime while criticizing it only for opportunistic reasons. Something that could not be stressed enough, since unfortunately it seems to escape both the media and the policymakers in the United States and Europe, is the fact that the overwhelming majority of Iranians perceive the nuclear issue as a national, not a regime, issue. This reality is so evident that Green Movement leaders, while criticizing the governments dangerous recklessness for the provocative way in which they have treated the nuclear issue, have gone so far as to also criticize Ahmadinejad for being too soft on the issue at the time when the Tehran Research Reactor (TRR) deal sponsored by Turkey and Brazil in May 2010 seemed to be prospering. Even more significantly, whereas the official line of the Iranian regime is that nuclear weapons are haram, or forbidden, for Muslims, those who have lived in Iran, or visited it in the past few years, have often had the occasion to hear opponents of the Islamic Republic, including some nostalgic for the monarchy, say that Iran, an ancient and proud country, has the right to have nuclear weapons because neighboring countries such as Pakistan and Russia, as well as Israel, have them. Yet, opponents of the present regime, and in particular the leaders of the Green Movement, are not obliged to passively toe the official line on the nuclear issue, nor would it be wise for them to try to out-nuclear the regime. There are ways to be critical of official policy and strategies and at the same time continue challenging the regime on authentically nationalist grounds. The reasoning one that does not question Irans national pride or its right to build a nuclear industry should rely on costs and priorities, both economic and political. It is true, and not at all a pretext, that Iran needs nuclear power in spite of its oil and gas resources. Any expert will tell you that given growing energy needs in a country with a young population and ambitions of industrial development, without the production of nuclear energy, it would become necessary to use a growing share of hydrocarbon production for internal

consumption, reducing exports. It is clear that Iran could not afford to do that without facing economic disaster. There are, however, many questions that should be raised. One is about alternatives. In the first place, oil and gas production are not a fixed quantity, but could, and should, be increased to cover a sizeable share of growing internal needs. It would be easy for those who are critical of the government to point out, for instance, that the decreasing not merely stagnating production of oil can be explained by the lack of international technology and investment: a shortfall that can be explained mainly by the impact of international sanctions prompted by Irans nuclear policy. The question is: how wise is it to weaken the production of one available kind of energy (hydrocarbons) in order to pursue another problematic source (nuclear)? Wouldnt it be more rational, and apt to produce more immediate results, to maximize what Iran already has instead of betting with so much priority and so much urgency on a process that can only produce results in the long term? How can one forget how long it has taken to build the Bushehr nuclear plant, still not producing energy after decades? The second economic consideration relates to the fact that uranium enrichment, which is indeed one of the rights guaranteed by the Non-Proliferation Treaty, turns out to be more expensive than the acquisition of low-enriched uranium from abroad. The regime talks about the need to escape dependency from politically unreliable sources, but this is exactly where the benefits of an international consortium, with all the necessary guarantees of supply, come in. Criticism of the nuclear policy of the regime, however, should be mainly political. Is the cost that the country is paying in terms of international isolation worth it? One can legitimately defend what is perceived as a right, but national interest should be focused on costs and benefits, and not only on principle. Without challenging Irans rights to enrich uranium, critics of the regime should talk about the issue in terms of wisdom and national interest. The vast majority of Iranians, sensitive though they may be to nationalist emotions, would rather favor an approach focusing on real benefits and real costs when addressing any issue. Last but not least, after the March 2011 nuclear catastrophe in Japan, it would be strange if the nuclear issue were to be addressed only in terms of security: economic security (the need to be able to count on independent sources of energy) and strategic security (for those who are in favor of acquiring

MIDDLE EAST PROGRAM OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES FALL 2011

nuclear weapons and deterrence against external threats). The issue today, which should be raised as a part of a platform for the future of a democratic Iran, should also be one of safety. In a country such as Iran, with one of the highest risks of major seismic events, a nuclear option for the production of energy should be subjected to strict scrutiny in terms of structural safety. Probably, the Green Movement should be green in the environmental sense as well. Of course this critical approach, focusing on alternatives, costs, and timing, has a chance of prevailing within Iranian public opinion only if: (1) a confrontation originating from the nuclear controversy is not brought to the extreme, (2) there is a possibility of compromise, and especially (3) if diplomacy succeeds in identifying formulas in which the right of Iran to enrich uranium is recognized (the zero centrifuge option can only be imposed on, and not accepted by, any conceivable Iranian regime, including the most democratic), while at the same time subjecting the Iranian nuclear program to both ordinary and special measures of monitoring and inspection. If this was the case, the nuclear issue could be de-dramatized, objectively recognized as not urgent, and brought back to economically rational proportions. If it is true that we want to assist the strengthening of the democracy movement in Iran, we should not forget that the nuclear issue, if addressed by us in an inflexible, intransigent, and worst-case mode, can only help the regime and embarrass its opponents, who are afraid of being seen as less patriotic. However, in trying to draft a basic political platform, the Green Movement should also avoid focusing excessively on the nuclear issue, but rather should try to contextualize it. It is very clear to Iranian democrats that the suspicions and hostilities aroused by the Iranian nuclear program have a lot to do with the nature of the Iranian regime. Shirin Ebadi, speaking about the issue, once said to a group of European ambassadors in Tehran: Nobody worries because France has nuclear weapons. A less provocative government in Tehran would go a long way toward de-dramatizing the issue, thus opening the way to acceptable compromise formulas giving guarantees of non-proliferation and national independence at the same time. If we turn to regional matters, we see that the regime and its opponents share the goal of having Iran recognized, and being able to act, as a key player. Here too, however, the discourse should shift from ideological principles to cost/benefit analysis, as well as to possible alternative means to pursue the same widely shared objectives, more effectively and at a lesser cost. Let us consider Afghanistan, a country whose importance for Iran cannot be underestimated, where the pursuit of Iranian influence can be justified both in terms of strategic security and in relation to the heavy social cost of the influx of drugs across the border. No Iranian government could ignore these objective considerations, but definitely there are different ways of addressing those goals. When Iran participated in the Bonn Conference on Afghanistan in a constructive way, after the defeat of the Taliban, it was certainly pursuing its national interest, while at the same time it was recognized as an important interlocutor and partner at a multilateral level. Iranian democrats should make it explicit that they believe this is the way that Iran should exert its influence in the country. The same can be said about possible alliances with different Afghan groups. It seems highly probable that the Iranian regime, while openly supporting the Karzai government, is at the same time hedging its bets by maintaining contacts and providing some assistance to certain groups within the Taliban camp. This policy, which some could defend as being realist, should be subjected to criticism for its ambiguity and for the political cost it involves: raising doubts and suspicions both in Afghanistan and in the international community about Tehrans real intentions. A very different and less counterproductive policy was Iranian support to the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance, where Tehran was not going alone, but in strict cooperation and coordination with both India and Russia. As for Iraq, here too Tehran has been more opportunistic than inspired by a grand plan. Iran has been hedging its bets, supporting both the government and radical Shia groups, such as the Sadrist militia, activating and de-activating them in order to exert influence. No Iranian government, even the most democratic, could ignore the need to have a role in Iraq, but it should clearly assess and question the price to pay for opportunism, ambiguity, and adventurism, which are often destined to backfire. The problem is not only opportunism, however. In addressing national interest issues, such as Afghanistan and Iraq, the present Iranian regime is also influenced by the more ideological, more radical, and less consensual dimensions of its foreign policy concept i.e. the outer circles I mentioned above. As far as regional issues are concerned, the Green Movement should also draw a sharp difference between these different levels, stressing that the pursuit of

Islamic and anti-imperialist goals interfere with and are harmful to national interest, by arousing suspicion both in the countries concerned and internationally and thus incurring isolation. The link between ideological and radical foreign policy and isolation is a very powerful one, and one which should be critically stressed within a foreign policy program of the Iranian opposition. This is also true for another area of interest to Irans regional policy: the Persian Gulf. It is enough to compare the present situation, with Gulf governments trying to prod the United States to a tough, uncompromising policy toward Iran, and the results of the patient and effective diplomatic work carried out both by President Rafsanjani and President Khatami in order to build bridges and pursue dialogue with the Gulf countries. Which option is more in harmony with national interest, both in terms of security and of the economy? An August 2011 Zogby poll shows a truly dramatic decline in Irans public image in the Arab Middle East since 2006. In 2006, favorable opinions of Iran were in the 80-90 percent range in Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. Today, with the exception of Lebanon (where 63 percent of the population approves of Iran) the approval rates are down to 37 percent in Egypt, 23 percent in the UAE, and 6 percent in Saudi Arabia. It would be difficult to describe this as a success for Iranian foreign policy, and the Green Movement should not miss any occasion to stress how harmful it is for Iran both in terms of national security and economic interest. As in the case of the nuclear issue, however, the possibility for the Green Movement to elaborate upon and propose a foreign policy program dealing with national interest issues in the region depends to a large extent on something that escapes it: U.S. policy toward Iran. Even while being able to contain and deter any attempt on the part of Iran to become the unquestioned dominant power in the region, the United States should operate on a clear and realistic premise: Iranian hegemony is not acceptable, Iranian exclusion is impossible. Iranian democrats, it is clear, will be able to propose a different way of defending national interest without ambiguities, without extremism and support of extremists, without

provocations only insofar as a real possibility of engagement and dialogue exists. This, of course, is a sort of Catch-22 predicament. The present Iranian regime knows that by its intransigent rhetoric and behavior it can sustain enough international hostility and enough suspicion of its intentions to prevent any real engagement and dialogue, thereby rendering impossible any alternative proposal for the pursuit of national security and, in general, national interest. If this perverse vicious circle is not broken, however, the chances of democracy in Iran will remain slim, in spite of all the protests and the widespread aspiration to real change. Late revolutionary regimes tend to replace revolutionary ideology with nationalism as a tool for consensus. This is also the case for the Iranian Islamic Regime. Messianism and apocalyptic scenarios are definitely not what really inspires the regime, nor what the regime thinks can rally the Iranian people. Nationalism is; nationalism works. What can be said, in any case, is that if we are serious when we say that we want to support Iranian democrats the best way to do it would be to break the vicious circle, so that Iranian democrats can seriously hope to be convincing when they say that they, and not the regime, are the true defenders of national interest, the true patriots, and that the foreign policy they seek is as we read in their February 23 Charter one of constructive engagement with the world.

NOTES

1 The Green Movement is a series of actions starting in 2009 before the contested presidential elections in June which saw the reelection of President Ahmadinejad. 2 Sariolghalam, Mahmood. The Evolution of the State in Iran: A Political Culture Perspective, Center for Strategic and Futuristic Studies, University of Kuwait, Kuwait, 2010, p. 48. 3 President Ahmadinejad first denied the Holocaust in December 2005 and has done so a number of times since then. 4 The Arab Spring refers to the wave of revolts and demonstrations in the Middle East which began in December 2010 in Tunisia and leading to the toppling of President Ben Ali, followed by the collapse of other regimes in the region.

ONE WOODROW WILSON PLAZA, 1300 PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE, NW, WASHINGTON, DC 20004-3027

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION OFFICIAL BUSINESS PENALTY FOR PRIVATE USE $300

MIDDLE EAST PROGRAM OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES FALL 2011

Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

President, Director, and CEO Jane Harman Board of Trustees Joseph B. Gildenhorn, Chair Sander R. Gerber, Vice Chair Federal Government Appointee Melody Barnes Public Citizen Members: James H. Billington, The Librarian of Congress; Hillary R. Clinton, Secretary, U.S. Department of State; G. Wayne Clough, Secretary, Smithsonian Institution; Arne Duncan, Secretary, U.S. Department of Education; David Ferriero, Archivist of the United States; James Leach, Chairman, National Endowment for the Humanities; Kathleen Sebelius, Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Private Citizen Members: Timothy Broas, John T. Casteen, III, Charles Cobb, Jr., Thelma Duggin, Carlos M. Gutierrez, Susan Hutchison, Barry S. Jackson Middle East Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 (202) 691-4000 www.wilsoncenter.org/middleeast

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Activating American Investment Overseas for a Freer, More Open WorldDocument32 pagesActivating American Investment Overseas for a Freer, More Open WorldThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Malaria and Most Vulnerable Populations | Global Health and Gender Policy Brief March 2024Document9 pagesMalaria and Most Vulnerable Populations | Global Health and Gender Policy Brief March 2024The Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Advance An Effective and Representative Sudanese Civilian Role in Peace and Governance NegotiationsDocument4 pagesHow To Advance An Effective and Representative Sudanese Civilian Role in Peace and Governance NegotiationsThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- The Cradle of Civilization Is in Peril: A Closer Look at The Impact of Climate Change in IraqDocument11 pagesThe Cradle of Civilization Is in Peril: A Closer Look at The Impact of Climate Change in IraqThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Women and Girls in WartimeDocument9 pagesWomen and Girls in WartimeThe Wilson Center100% (1)

- Activating American Investment Overseas For A Freer, More Open WorldDocument32 pagesActivating American Investment Overseas For A Freer, More Open WorldThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Restore Peace, Unity and Effective Government in Sudan?Document4 pagesHow To Restore Peace, Unity and Effective Government in Sudan?The Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Managing Water Scarcity in An Age of Climate Change: The Euphrates-Tigris River BasinDocument13 pagesManaging Water Scarcity in An Age of Climate Change: The Euphrates-Tigris River BasinThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Public Perceptions On Climate Change in QatarDocument7 pagesPublic Perceptions On Climate Change in QatarThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Palestinian Women Facing Climate Change in Marginalized Areas: A Spatial Analysis of Environmental AwarenessDocument12 pagesPalestinian Women Facing Climate Change in Marginalized Areas: A Spatial Analysis of Environmental AwarenessThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Localizing Climate Action: The Path Forward For Low and Middle-Income Countries in The MENA RegionDocument9 pagesLocalizing Climate Action: The Path Forward For Low and Middle-Income Countries in The MENA RegionThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- ECSP Report: Population Trends and The Future of US CompetitivenessDocument17 pagesECSP Report: Population Trends and The Future of US CompetitivenessThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Recalibrating US Economic Engagement With Africa in Light of The Implementation of The AfCFTA and The Final Days of The Current AGOA AuthorizationDocument8 pagesRecalibrating US Economic Engagement With Africa in Light of The Implementation of The AfCFTA and The Final Days of The Current AGOA AuthorizationThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Investing in Infrastructure Bolsters A More Stable, Free and Open WorldDocument2 pagesInvesting in Infrastructure Bolsters A More Stable, Free and Open WorldThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- West and North Africa at The Crossroads of Change: Examining The Evolving Security and Governance LandscapeDocument13 pagesWest and North Africa at The Crossroads of Change: Examining The Evolving Security and Governance LandscapeThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Conference ReportDocument28 pagesConference ReportThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Africa's Youth Can Save The WorldDocument21 pagesAfrica's Youth Can Save The WorldThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- InsightOut Issue 7 - Turning The Tide: How Can Indonesia Close The Loop On Plastic Waste?Document98 pagesInsightOut Issue 7 - Turning The Tide: How Can Indonesia Close The Loop On Plastic Waste?The Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Lessons Learned From State-Level Climate Policies To Accelerate US Climate ActionDocument9 pagesLessons Learned From State-Level Climate Policies To Accelerate US Climate ActionThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Africa's Century and The United States: Policy Options For Transforming US-Africa Economic Engagement Into A 21st Century PartnershipDocument8 pagesAfrica's Century and The United States: Policy Options For Transforming US-Africa Economic Engagement Into A 21st Century PartnershipThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Reimagining Development Finance For A 21st Century AfricaDocument11 pagesReimagining Development Finance For A 21st Century AfricaThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Addressing Climate Security Risks in Central AmericaDocument15 pagesAddressing Climate Security Risks in Central AmericaThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Accelerating Africa's Digital Transformation For Mutual African and US Economic ProsperityDocument9 pagesAccelerating Africa's Digital Transformation For Mutual African and US Economic ProsperityThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- New Security Brief: US Governance On Critical MineralsDocument8 pagesNew Security Brief: US Governance On Critical MineralsThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- US-Africa Engagement To Strengthen Food Security: An African (Union) PerspectiveDocument7 pagesUS-Africa Engagement To Strengthen Food Security: An African (Union) PerspectiveThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Africa Year in Review 2022Document45 pagesAfrica Year in Review 2022The Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Avoiding Meltdowns + BlackoutsDocument124 pagesAvoiding Meltdowns + BlackoutsThe Wilson Center100% (1)

- InsightOut Issue 8 - Closing The Loop On Plastic Waste in The US and ChinaDocument76 pagesInsightOut Issue 8 - Closing The Loop On Plastic Waste in The US and ChinaThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Moments of Clarity: Uncovering Important Lessons For 2023Document20 pagesMoments of Clarity: Uncovering Important Lessons For 2023The Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Pandemic Learning: Migrant Care Workers and Their Families Are Essential in A Post-COVID-19 WorldDocument18 pagesPandemic Learning: Migrant Care Workers and Their Families Are Essential in A Post-COVID-19 WorldThe Wilson CenterPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Days of PurgatoryDocument20 pagesDays of PurgatoryIulian StamaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sobre o Sistema de FarahidiDocument331 pagesSobre o Sistema de Farahidipostig100% (1)

- OccultationDocument172 pagesOccultationQanberPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter IIIDocument9 pagesChapter IIIZirumi DauzPas encore d'évaluation

- PST JSTUCWisePositionsDocument35 pagesPST JSTUCWisePositionsferozuddinnohri67% (9)

- English Assignment: Antonyms and SynonymsDocument6 pagesEnglish Assignment: Antonyms and SynonymsA Latif MangrioPas encore d'évaluation

- Pastor. The History of The Popes, From The Close of The Middle Ages. 1891. Vol. 10Document568 pagesPastor. The History of The Popes, From The Close of The Middle Ages. 1891. Vol. 10Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (3)

- Serbian Heritage in Kosovo and Metohia Explored Between Fact and FictionDocument111 pagesSerbian Heritage in Kosovo and Metohia Explored Between Fact and FictionJelenaJovanović100% (1)

- Script Brigada PagbasaDocument4 pagesScript Brigada PagbasaKristine M. Almazan100% (1)

- Malcolm X Reading ComprehensionDocument5 pagesMalcolm X Reading ComprehensionAlicia Martin SanchezPas encore d'évaluation

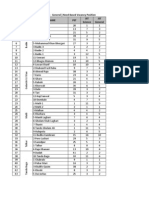

- Sinopec Safety Orientation Sign-In SheetDocument10 pagesSinopec Safety Orientation Sign-In SheetAhmad RazaPas encore d'évaluation

- SQP 20 Sets HistoryDocument123 pagesSQP 20 Sets Historyhumanities748852Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gala (Priests)Document2 pagesGala (Priests)mindhuntPas encore d'évaluation

- Act 1 and 2 AnswerDocument9 pagesAct 1 and 2 AnswerTomasPas encore d'évaluation

- Social DarwinismDocument20 pagesSocial DarwinismStephan Wozniak100% (1)

- Agape - November, 2013Document36 pagesAgape - November, 2013Mizoram Presbyterian Church SynodPas encore d'évaluation

- Kodish2013 PDFDocument22 pagesKodish2013 PDFGonzalo BORQUEZ DIAZPas encore d'évaluation

- Lovely Poetry of RomiDocument11 pagesLovely Poetry of RomiNaeem Uddin100% (5)

- ConfuciusDocument42 pagesConfuciusLei Marie RalaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Doctrine of ScripturesDocument38 pagesThe Doctrine of ScripturesdanilkumarinPas encore d'évaluation

- Nelson Mandela's Inaugural Speech 1994Document9 pagesNelson Mandela's Inaugural Speech 1994girmaneway768462Pas encore d'évaluation

- Index For K M Ganguli Mahabharat EbookDocument4 pagesIndex For K M Ganguli Mahabharat EbookgandhervaPas encore d'évaluation

- Liberty and Individuality in Mill's On LibertyDocument20 pagesLiberty and Individuality in Mill's On LibertyJesseFariaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Zohar: Pritzker Edition Reflects A Reconstructed Aramaic Text, BasedDocument8 pagesThe Zohar: Pritzker Edition Reflects A Reconstructed Aramaic Text, BasedDavid Richard JonesPas encore d'évaluation

- G. E. Adibe - Mysticism in African Traditional Religion (Northern Igbo Cultural Area Experience)Document377 pagesG. E. Adibe - Mysticism in African Traditional Religion (Northern Igbo Cultural Area Experience)sector4bk100% (1)

- All My SonsDocument6 pagesAll My SonsEmily Gong100% (6)

- Van Til Common Grace and The GospelDocument156 pagesVan Til Common Grace and The Gospelbill billPas encore d'évaluation

- 0029 - I Gotta Split! - IIDocument4 pages0029 - I Gotta Split! - IIFollowGodPas encore d'évaluation

- Ankh - Gods of Egypt: Rules ClarificationsDocument3 pagesAnkh - Gods of Egypt: Rules ClarificationsFernandoPas encore d'évaluation

- SimpatikaDocument12 pagesSimpatikaNarti Ummi MalichahPas encore d'évaluation