Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Wang and Chen

Transféré par

yonasabraham266Description originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Wang and Chen

Transféré par

yonasabraham266Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

African Journal of Business Management Vol. 5(17), pp. 7616-7621, 4 September, 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.

org/AJBM ISSN 1993-8233 2011 Academic Journals

Full Length Research Paper

Consumers attitudes towards different product category of private labels

Shih Jung Wang1 and Lily Shui-Lien Chen2*

1

Business Administration Department, Hsing Wu College, No. 101, Sec.1, Fenliao Rd., LinKou Township, New Taipei City 244, Taiwan. 2 Graduate Institute of Management Sciences, Department of Management Sciences and Decision Making, Tamkang University, No. 151, Ying-Chuan Road, Tamsui, New Taipei City 25137, Taiwan (R.O.C.).

Accepted 6 July, 2011

This research attempted to investigate the consumer perceptions on product quality, price, brand leadership and brand personality towards convenience goods and shopping goods based on international private labels (IPLs) and local private labels (LPLs). Data were collected outside the entrances of the main rail station of Taipei, Taiwan. A systematic sampling was adopted and 254 questionnaires were eventually collected. The findings revealed that the consumers in Taiwan believe that international and local hypermarkets both produce better convenience goods than shopping goods that have high quality and deliver more value. This research represents one of the few pioneer works that empirically investigate the aforementioned issues. Key words: International private label, local private label, convenience goods, shopping goods. INTRODUCTION In recent years, large retailers have exercised private label (PL) strategies to reap the ever-increasing market share in most consumers product categories when competing with national brands (Cheng et al., 2007; Ishibashi and Matsushima, 2009). For example, Wal-Mart, a leading retailer in the USA, the sales volume of PL has accounted for as much as 25% of the operating revenues. In grocery outlets, they form over 15% of US supermarket sales and over 44% grocery shoppers regularly buy PL (Chen, 2007). In Switzerland, where the top 5retailers capture up to 88% of the market, the number of PL (38% of business is private labeled) makes Switzerland the most PL country in the world. In Great Britain, 31% of total business is composed of PL, which owns an 83% share of sales in the retailing sector (Anonymous, 2004). PL, also store brand, is the brand which retailers are responsible for promoting, shelf placing, pricing, and positioning its own brand in the product space. In this study, we group the PL into two categories that is, the international private label (IPL) for example, American Costco and British Tesco, and the local private label (LPL) for example, Taiwanese RT-Mart. Taiwanese consumers perceive that these two categories of PL are different in some ways. Meanwhile, product classification, for example, convenience goods versus shopping goods, can also affect consumers attitudes toward these brands. The notion of national brands (NBs) and PL have been heavily studied in the marketing literature (Sanjoy and Oded, 2001; Karray and Martn-Herrn, 2009). Most of them attempt to compare consumer perceptions of product quality and price among different brands. However, there are few articles that distinguish the different effects on IPL and LPL and there are few researches work that introducing or show the effect of different product classification on such in this matter. This research, therefore, investigates the attitudes of Taiwanese consumers towards convenience goods and shopping goods based on two types of brands: IPL and LPL. This research is organized as follows: literature review and research hypotheses are presented in the next

*Corresponding author. E-mail: tzjunltk@yahoo.com.tw Tel: 886-2-86313221/886-926-973473, Fax: 886-2-86313214. Abbreviations: IPLs, International private labels; LPLs, local private labels; PL, private label; NBs, national brands; IG, intergenerational; CFA, confirmatory factor analysis; CFI, category for Inference; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; CR, composite reliability; AVE, average variance explained; SAS, statistical analysis software.

Wang and Chen

7617

section. In Section 3, we will discuss the method used in the paper. The data analysis and results are shown in Section 4. This paper is then concluded in the final section. LITERATURE HYPOTHESES REVIEW AND RESEARCH

Brand American Core Values. Price perception The price of an item plays a powerful role in marketing. Consumers see price more than just the money that the buyer hands over to the seller. The broader view is that the price is the sum of all the values that the buyer exchanges for obtaining the product. Thus price is a key variable in communicating to the customer about the value of the product. The shoppers perceptions of price are regarded to influence their purchase behavior (Miranda and Joshi, 2003). Thus, the lower the price, the more favorable the brand perception. Brand personality Aaker (1997) defines brand personality as the set of human characteristics or traits that consumers attribute to a brand. Aaker (1996) describes brand personality as the linkage to the emotional and self-expressive benefits of a brand. Boyle (2003) advocates that, a key aspect of a brands personality is its values and therefore, one of the tasks of brand builders is to find a way of imbuing the brand with these values. Though it is no easy work to imbue a brand with the values, nevertheless, the brand personality must be distinctive, robust, desirable, and consistent enough to successfully differentiate it from another brand. Research hypotheses Consumer products are those that are purchased by the final consumer for his/her consumption. These products are further classified into convenience, shopping, specialty. This research will focus on convenience goods and shopping goods. Convenience goods are those that are purchased frequently with little planning or shopping effort. They are usually at low prices and widely available. Shopping goods are those which are purchased less frequently, such as furniture and major appliances, and are compared on the bases of suitability, quality, price and style (Kotler et al., 1998). Empirical evidence indicates that retail concentration has increased dramatically throughout Europe as supermarkets take an increasing share of the convenience goods business (Cullen, 1997). Retailers have offered convenience goods as their PLs for a long time now in many countries. Sometimes these products represent a prime product type for brand imitation. Consumers will buy a brand imitator instead of an original if they do not perceive significant differently on product quality given the price difference. Astous and Gargouri (2001) indicate the goodness of the imitation may be of

Some companies license their PLs and then launch new businesses. They sometimes search for manufacturers with excess capacity to produce their PL at a lower cost, and then earn a higher profit margin (Parker and Kim, 1997; Gmez and Benito, 2008). The past two decades have seen manufacturers brands becoming less important. Meanwhile, retailers have been growing in influence and gaining power in the marketing channel (Farris and Kusum, 1992; Shocker et al., 1994; Frederick, 2000; Surez, 2005). The various arenas of NBs and PLs take place and the PLs possess unique competitive means to control the market power of NBs, including price, shelf space, quality, innovation and brand advertising (Steiner, 2004). This research distinguishes two types of PLs namely IPL and LPL. The purpose of this paper is to investigate consumers perceptions towards convenience goods and shopping goods based on IPL and LPL qualities. First, the study defines the constructs used in this paper and their application. It then proposes the viewpoints by raising a number of hypotheses. There are four constructs to be discussed namely, perceived quality, brand leadership, price perception, and brand personality. These constructs will be discussed in relation to two product categories which are the convenience goods and shopping goods. Perceived quality According to Aaker and Joachimsthaler (2000), perceived quality is a special type of association, because it influences brand associations in many contexts and has been empirically shown to affect profitability. It is also defined as the consumers judgment about a products overall excellence or superiority (Chueh and Kao, 2004). Brand leadership According to Aaker and Joachimsthaler (2000), brand leadership is an excellent, interesting, insightful and thought-provoking draw that significantly extends the boundaries of what we know about managing brands. Aaker (1996) develops three dimensions to interpret leadership. These are syndrome, innovation and dynamics of customer acceptance. Steiner (2004) regards innovation as the most important of all. Stefan and Don (2003) also indicate that innovation is one of the National

7618

Afr.J.Bus. Manage.

less importance as long as the quality appears to be there. In an empirical study done by Leblanc and Turley (1994), only an average of 2.19 brands can be remembered from a consideration set sizes of 23 shopping goods. In the research conducted by LeBlanc and Turkey (1994) and LeBlanc and Herndon (2001), they record that consumers seem to have initial evoked sets with only a single brand in them. Baker and Wilkie (1992) have the same results reporting that consumers have small-evoked set sizes for shopping goods. When they compared convenience goods and shopping goods, Murphy and Ben (1986) found out that the former has lower risk and effort than the latter. On a concept of intergenerational (IG) influence research, Heckler et al. (1989) discovered that consumers have stronger preference effects for convenience goods than for shopping goods (Moore et al., 2002). Therefore, the study proposes the following hypotheses. H1. Consumers perceive that the quality of convenience goods is superior to that of shopping goods for private label. H2. Consumers perceive that brand leadership of convenience goods is superior to that of shopping goods for private label. H3. Consumers perceive that the price of convenience goods is higher than that of shopping goods for private label. H4. Consumers are more conscious of the brand personality for convenience goods than for shopping goods for private label.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY In this section, we discuss the research setting, scale development, as well as the sampling framework. Research setting As mentioned earlier on, this research seeks to investigate consumer perception of two product categories among two different labels. We therefore compare consumers attitude toward IPL, and LPL between convenience goods and shopping goods. The study considers a liquid detergent as the convenience good in the research based on Cullens (1997) work. There are many hypermarkets in Taiwan. However, this research chose two of them to be the research subjects. Not only are these hypermarkets well known, but they also have their own store brands in many product categories. TESCO (merged with Carrefour in Taiwan) liquid detergent (one of the store-brand products of British Tesco Co.) and FP liquid detergent (a PL by a local Taiwanese RT-Mart) are our IPL and LPL, respectively. We choose the electronic appliance as the item representing shopping goods based on the paper by Varinder and Krish (2001). As pointed out earlier on TESCO and FP are our IPL and LPL, respectively. Scale development The questionnaire was developed mostly according to the scales of

Aaker (1996) and Miranda and Joshi (2003), but with some minor modifications that fit our research purpose. The measurement items of price perception are cited from Miranda and Joshi (2003). In addition, the study takes into consideration the classification by Aaker (1996) on measuring brand equity across products and markets. All items were measured as perceptions on a 7-point Likert scale: 1=strongly disagree, 4=neutral and 7=strongly agree. The interviewees were asked about their perceptions toward IPL, and LPL products. Finally, the study adopted four sets of items that are discussed below as follows. Each scale of perceived quality, brand leadership, and brand personality contain three items. The Item-total value of the price construct suggested the elimination of item 2 and the amount of the final measurement items for price perception is only one. The items of perceived quality are high quality, the worst brand, and consistent quality. Leadership scale contains innovative, growing in popularity, and the leading brand. Price perception scale is comprised of lower; has a personality, interesting, and clear image of the type of users. These items are related to the brand personality scale.

Sampling and data collection Taipei, the metropolis of Taiwan, is selected as the target population in this research. The survey was administered to the Taiwanese residents at the public location (Taipei railway station) with the systematic sampling method (one out of ten passing entrance). After discarding some invalid respondents, we collected a total sample size of 254 for the final data analysis.

DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTS A series of statistical procedures are used to analyze the research questions. The respondents profile will be reported first, followed by an examination of the reliability of the scales. Testing of the research hypotheses will then be placed at the end of this section. Respondents profiles The respondents included more females (60.63%) than males (39.37%). Most of them were less than 30 years of age. About 91.74% of the respondents held a university/college degree or higher. As for their occupation, white collar workers, blue collar workers, and students all occupied around one third of the respondents. In terms of income, about 45% earned total monthly incomes of NT$15,000 or less. Finally, most of the respondents were single. Detailed descriptive statistics relating to the respondents profiles are shown in Table 1.

Measurement accuracy analysis A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on the sample data in order to get evidence on the robustness and reliability of the scales in a brand equity context. The CFA model had an overall Chi-square of 225.10, a category for Inference (CFI) of 0.97, an IFI of

Wang and Chen

7619

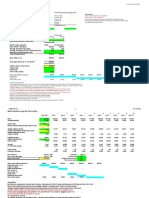

Table 1. Participants demographic statistics.

Age 20 21-30 31-40 41-50 51 Occupation White collars Blue collars Jobless Students Gender Male Female

Freq 90 109 32 14 9 Freq 78 77 9 90 Freq 100 154

% 35.43 42.91 12.60 5.51 3.54 % 30.71 30.31 3.54 35.43 % 39.37 60.63

Marriage Married Single Widow (er) Education senior high school College/university Graduate Monthly income NT$15,000 NT$15001-NT$30,000 NT$30,001-NT$45,000 NT$45001-NT$60,000 60,001

Freq 53 200 1 Freq 21 210 23 Freq 114 66 46 13 15

% 20.87 78.74 0.39 % 8.27 82.68 9.06 % 44.88 25.98 18.11 5.12 5.91

Table 2. Measurement accuracy analysis statistics.

Core construct Perceived quality

Brand leadership Price perception Brand personality

* Not applicable

Factor loading 0.84 0.52 0.83 0.70 0.87 0.82 0.65 0.78 0.67 0.69

T value 38.78 20.68 38.15 29.94 41.32 37.56 23.25 33.04 27.45 28.21

Cronbachs 0.77

Composite reliability 0.78

AVE 0.55

0.83 n.a.* 0.76

0.84 n.a.* 0.76

0.64 0.90 0.51

0.97, a NNFI of 0.96 and a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.065. The CFI, IFI, and NNFI measures fall above the recommended value of 0.9 and RMSEA is below the recommended value of 0.08. All of the item loadings were satisfactory and the t-values were significant. Thus, the fit of the model is good. Related reliability and validity assessment followed. Coefficient alpha values, composite reliability (CR) indexes and an average-variance-explained (AVE) value of the 6 dimensions were computed for reliability tests. All the alpha, CR and AVE values shown in Table 2 exceeded generally recommended levels of 0.6, 0.6 and 0.5, respectively (Shook et al., 2004). Thus, the results provided evidence of reliability. As for the test of validity, examining significant t-value factor loadings checked for convergent scale validity. Table 2 shows significant t-values, ranging from 20.68 to 41.32. The AVE score, achieved for the entire model constructs, for each factor being over the minimum threshold of 0.5 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981) and ranged from 0.51 to 0.90. Considering

the evidence of reliability and validity, the scales should be considered generally reliable and valid overall. Individual scale items and test summary related to research construct accuracy are shown in Table 2. Hypotheses testing The statistical analysis software (SAS) package is used in this study. The t-tests are used to compare the consumers perception on both convenience goods and shopping goods within a company. As can be seen from Table 3, in terms of the perceptions of IPL (British Tesco) and LPL (Taiwanese RT-Mart) across the 4 factors, there was a great degree of homogeneity in the convenience and shopping goods except quality perceptions. Its credible that consumers perceived the quality for convenience goods to be better than shopping goods. Therefore, H1 is accepted. This denoted that customers in Taiwan believed the hypermarkets with more effort and

7620

Afr.J.Bus. Manage.

Table 3. Comparison between convenience and shopping goods for IPL/LPL.

Factor Quality Leadership Price Personality

IPL (British Tesco) Convenience Goods1 Shopping Goods2 4.30 4.12 3.77 3.74 4.22 4.18 3.91 3.81

p-value5 0.0270* 0.7856 0.6611 0.2771

LPL ( Taiwanese RT-Mart) Convenience Goods3 Shopping Goods4 3.98 3.70 3.44 3.41 4.63 4.43 3.62 3.58

p-value5 0.0003* 0.7532 0.0843 0.6294

1, Mean values for convenience goods on IPLs, based on a 7 Likert-type scale with strongly disagree; 7, to strongly agree; 1, mean values for shopping goods on IPLs, based on a 7 Likert-type scale with strongly disagree; 7, to strongly agree; 1, mean values for convenience goods on LPLs based on a 7 Likert-type scale with strongly disagree; 7, to strongly agree; 1, mean values for shopping goods on LPLs based on a 7 Likert-type scale with strongly disagree; 7, to strongly agree; 5, significant level; *, significant different (at 0.05 level) for convenience goods and shopping goods.

experience on convenience goods are better than shopping goods. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION This research investigated the consumer perceptions of IPL and LPL on convenience goods and shopping goods categories in Taiwan. Most of previous works have focused on NBs and private brands only, but we distinguish PL into IPL and LPL. Since Taiwan is getting more internationalized, more and more international businesses come to the island. Therefore, it is important to understand how consumers perceive these private branders. The mean value of consumers perception on convenience goods is significantly higher than that of shopping goods. That is to say the consumers in Taiwan believe that these two hypermarkets produce better convenience products than shopping products in quality and deliver more values to the customers. IPL has the advantage of economies of scale and the image of commodities of foreign make, which manifests itself as exotic lifestyle and culture. LPL received the lowest score in almost all aspects, which means that consumers do not regard highly this label. But convenience goods branders of this label can make use of the advantage of their low price strategy. For shopping goods, the study suggests the branders emphasize the origin of those products. Findings from the comparison of convenience and shopping goods for IPL/LPL, show that customers perceived shopping goods inferior to convenience goods. Retailers should make more effort to create high value shopping goods, especially on quality conception enhancement. LIMITATIONS RESEARCH AND DIRECTION TO FURTHER

work of Aaker (1996) and Miranda and Joshi (2003). Their objectives are to measure brand equity without subject to any specific product categories. Though the study adopt only four constructs to measure Taiwanese consumer perceptions on two different brand types, most of the results support the viewpoint. That means, the study was able to measure consumer perceptions using these constructs. The study does not use the whole original scale, but this could be an interesting issue for further study. There is little research distinguishing IPL and LPL from PLs. The findings indicate that consumers have different perceptions on these two brand types. This calls for marketers to exploit the opportunities in these segments. Finally, the research approach and findings of this study can provide directions for future research. Future study could follow the research approach to get more empirical evidence by adopting different categories, brands, as well as focusing on different countries other than Taiwan.

REFERENCES Aaker DA (1996). Measuring brand equity across products and market. California Manage. Rev., 38(3): 102-120. Aaker DA, Joachimsthaler E (2000). Brand Leadership. The Free Press, New York, NY. Aaker JL (1997). A Brand Personality Scale, BPS: The Big Five. J. of Market. Res., 34(3): 347-356. Anonymous (2004). Retailers push private label, Beverage Industry. 95(6): 20. Astous A, Gargouri E (2001). Consumer evaluations of brand imitations. Eur. J. Market., 35(1/2): 153. Baker WE, Wilkie WL (1992). Factors affecting information search for consumer durables. Working Paper 92-115. Marketing Science Institute, Cambridge, MA, May. Boyle E (2003). A study of entrepreneurial brand building in the manufacturing sector in the UK. J. Prod. Brand Manage., 12(2/3): 79-93. Chen HH (2007). A study of factors affecting the success of private label brands in Chinese e-market. J. Technol. Manage. in China, 2(1): 38-53. Cheng JMS, Chen LSL, Lin JYC, Wang EST (2007). Do consumers perceive differences among national brands, international private labels and local private labels? The case of Taiwan, J. Prod. Brand Manage., 16(6): 368-376. Chueh TY, Kao DT (2004). The moderating effects of consumer perception to the impacts of country-of-design on perceived quality. J.

This paper tests the hypotheses by conducting the survey method. The study adopts part of the constructs from the

Wang and Chen

7621

of Am. Acad. of Bus., Cambridge. 4(1/2): 70-74. Cullen B (1997). A study of the trapped brand phenomenon. Irish Marketing Review. 10(1): 3-14. Farris PW, Kusum A (1992). Retail Power: Monster or Mouse? J. Retailing, 68: 351-369. Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981). Evaluating structural models with unobserved variables and measurement error. J. of Market. Res., 18(February): 35-90. Frederick EW Jr. (2000). Understanding the relationships among brands, consumers, and resellers. Acad. Market. Sci., 28(1): 17-23. Gmez M, Benito NR (2008). Manufacturers characteristics that determine the choice of producing store brands. Eur. J.Market., 42(1/2): 154-177. Heckler SE, Childers TL, Arunachalam R (1989). Intergenerational Influences in Adult Buying Behaviors: An Examination of Moderating Factors. Adv. in Cons. Res., 16: 276-284. Ishibashi I, Matsushima N (2009). The Existence of Low-End Firms May Help High-End Firms. Market. Sci., 28(1): 136-147. Karray S, Martn-Herrn G. (2009). A dynamic model for advertising and pricing competition between national and store brands. Eur. J. of Operat. Res., 193(2): 451-467. Kotler P, Armstrong A, Brown L, Adam S (1998). Marketing, Prentice-Hall, Canberra. LeBlanc RP, Herndon NC Jr. (2001). Cross-cultural consumer decisions: Consideration sets--a marketing universal? Marketing Intelligence & Planning. 19(6/7): 500-506. LeBlanc RP, Turley LW (1994). Retail influence on evoked set formation and final choice of shopping goods. Int. J. of Retail , Distribution Manage., 22(7): 10-17. Miranda MJ, Joshi M (2003). Australian retailers need to engage with private labels to achieve competitive difference. Asia Pacific J. of Market. and Logistics. 15(3): 34-47. Moore ES, Wilkie WL, Lutz RJ (2002). Passing the torch: Intergenerational influences as a source of brand equity. J. of Market., 66(2): 17-37.

Murphy PE, Ben EE (1986). Classifying Products Strategically. J. of Market. Res., 50(July): 2442. Parker P, Kim N (1997). National brands versus private labels: An empirical study of competition, advertising and collusion. Eur. Manage. J., 15(3): 220-235. Sanjoy G., Oded L (2001). Perceptual positioning of international, national and private brands in a growing international market: an empirical study. J. Brand Manage., 9(1): 45-62. Shocker AD, Rajendra KS, Robert WR (1994). Challenges and Opportunities Facing Brand Management: An Introduction to the Special Issue. J. Market. Res., 31(May): 149-158. Shook CL, David JK Jr, Hult GTM, Kacmar MK (2004). An Assessment of the Use of Structural Equation Modeling in Strategic Management Research. Strateg. Manage. J., 25(4): 397404. Stefan PJ, Don F (2003). National Brand Identity & Its Effect on Corporate Brands: The Nation Brand Effect (NBE). Multinational Business Review. 11(2): 99-113. Steiner RL (2004). The nature and benefits of national brand/private label competition. Rev. of Ind. Organ., 24(2): 105-127. Surez MG (2005). Shelf space assigned to store and national brands: A neural networks analysis. Int. J. of Retail & Distribution Manage., 33(11/12): 858-878. Varinder MS, Krish S K (2001). Recognizing the importance of consumer bargaining: Strategic marketing implications. J. of Market. Theory and Practice, 9(1): 24-37.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Business Research Dissertation: Student preference on food brands in Tesco stores in the North East of UKD'EverandBusiness Research Dissertation: Student preference on food brands in Tesco stores in the North East of UKPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Consumers Choose Second Best BrandsDocument8 pagesWhy Consumers Choose Second Best BrandsHaris AminPas encore d'évaluation

- Modeling Consumer AttitudesDocument17 pagesModeling Consumer AttitudessahinchandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Relevance Versus Convenience in Business Research: The Case of Country-of-Origin Research in MarketingDocument33 pagesRelevance Versus Convenience in Business Research: The Case of Country-of-Origin Research in MarketingAmbreen AtaPas encore d'évaluation

- Brand Loyalty Factors Differ Between Thailand and VietnamDocument11 pagesBrand Loyalty Factors Differ Between Thailand and VietnamAdina MariaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer Based GloblaDocument20 pagesConsumer Based GloblaBatica MitrovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Extrinsic and Intrinsic Cue EffectsDocument10 pagesExtrinsic and Intrinsic Cue Effectsroy royPas encore d'évaluation

- Admin1, IJRBS Akkucuk 1 16Document16 pagesAdmin1, IJRBS Akkucuk 1 16pgdm23avinashaPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Sell White Lable ProductDocument35 pagesHow To Sell White Lable ProductHeru Muara SidikPas encore d'évaluation

- Brand Origin in An Emerging Market: Perceptions of Indian ConsumersDocument20 pagesBrand Origin in An Emerging Market: Perceptions of Indian ConsumerssindhulsaxenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Decision-Making Behaviour Towards Casual Wear Buying: A Study of Young Consumers in Mainland ChinaDocument10 pagesDecision-Making Behaviour Towards Casual Wear Buying: A Study of Young Consumers in Mainland ChinaHarish VermaPas encore d'évaluation

- Disserr LitraDocument17 pagesDisserr LitraDisha GangwaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer PerceptionsDocument10 pagesConsumer PerceptionsSyahridzuel Ulquiorra SchifferPas encore d'évaluation

- Byron SharpDocument27 pagesByron SharpAlper AslanPas encore d'évaluation

- Pawan Dissertation ReportDocument6 pagesPawan Dissertation ReportsweelalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Exploring UK Fashion Buyers' and Merchandisers' Job RolesDocument26 pagesExploring UK Fashion Buyers' and Merchandisers' Job RolesARIEL GARCIA NUÑEZPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer Perceptions of Global and Local Brands: Research ArticleDocument10 pagesConsumer Perceptions of Global and Local Brands: Research ArticlerohanPas encore d'évaluation

- For Review Only: Consumer Buying Behaviour A Factor of Compulsive Buying Prejudiced by Windowsill PlacementDocument19 pagesFor Review Only: Consumer Buying Behaviour A Factor of Compulsive Buying Prejudiced by Windowsill Placementjj9821Pas encore d'évaluation

- Antecedents and Consequences of Brand Equity - A Meta-AnalysisDocument24 pagesAntecedents and Consequences of Brand Equity - A Meta-Analysisseema100% (1)

- Explaining The Product-Specificity of Count Ry-Of - Origin EffectsDocument32 pagesExplaining The Product-Specificity of Count Ry-Of - Origin EffectsBijuterii Hand MadePas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer Attitude-New Trends and Direction in PLB With Comparison With National BrandDocument10 pagesConsumer Attitude-New Trends and Direction in PLB With Comparison With National BrandAssociation for Pure and Applied ResearchesPas encore d'évaluation

- Article For Private LabelDocument11 pagesArticle For Private LabelArpit RastogiPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International JournalDocument19 pagesJournal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International JournalAmit KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- 495 JLS S1 501 Hmrdi 34Document9 pages495 JLS S1 501 Hmrdi 34rohanPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumers' Purchase Intentions for Foreign ProductsDocument8 pagesConsumers' Purchase Intentions for Foreign ProductszaykrolPas encore d'évaluation

- Factors Influencing Consumers' Purchase Decision of Private Label Brand ProductsDocument10 pagesFactors Influencing Consumers' Purchase Decision of Private Label Brand ProductsRezkyPas encore d'évaluation

- Brand and Branding, Research Findings and Future PrioritiesDocument20 pagesBrand and Branding, Research Findings and Future PrioritiesManisha BarthakurPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal Brand ImageDocument10 pagesJurnal Brand ImagemaretiwulandariPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer Attitudes and Loyalty Towards Private BrandsDocument11 pagesConsumer Attitudes and Loyalty Towards Private BrandsAnoushka SequeiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review GodrejDocument6 pagesLiterature Review GodrejArchana Kalaiselvan100% (2)

- Consumer Perception of Shopping MallsDocument14 pagesConsumer Perception of Shopping MallsEkramul Hoda0% (1)

- Measuring National Brand Equity over Store BrandsDocument28 pagesMeasuring National Brand Equity over Store BrandsSandeep KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - 1 Jurnal Kosmetik WardahDocument17 pages1 - 1 Jurnal Kosmetik WardahMariyya UlfahPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Methods For Strategic ManagersDocument15 pagesResearch Methods For Strategic ManagersShamim Ahmed Mozumder Shakil67% (3)

- Antecedents of Lux Brand Purchase IntentionsDocument15 pagesAntecedents of Lux Brand Purchase IntentionsOtilia OlteanuPas encore d'évaluation

- Customer Perceptions On Private Label Brands in Indian Retail IndustryDocument20 pagesCustomer Perceptions On Private Label Brands in Indian Retail IndustrySuresh UchihaPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis Brand AwarenessDocument5 pagesThesis Brand Awarenessamywellsbellevue100% (2)

- Inferring Market StructureDocument12 pagesInferring Market StructuremazanecPas encore d'évaluation

- Intention-Behavior Discrepancy of Foreign Versus Domestic Brands in Emerging Markets: The Relevance of Consumer Prior KnowledgeDocument49 pagesIntention-Behavior Discrepancy of Foreign Versus Domestic Brands in Emerging Markets: The Relevance of Consumer Prior KnowledgeGeorges E. KalfatPas encore d'évaluation

- Country of Origin Effects and Consumer Based Brand Equity: July 2000Document6 pagesCountry of Origin Effects and Consumer Based Brand Equity: July 2000Maddy BashaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer Perception On Private Label Products in CoimbatoreDocument15 pagesConsumer Perception On Private Label Products in CoimbatorekocasPas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of Brands On Consumer Buying Behavior: An Empirical Study On Smartphone BuyersDocument17 pagesThe Impact of Brands On Consumer Buying Behavior: An Empirical Study On Smartphone BuyersEwebooPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer Centered "Brand Value" of Foods: Drivers and SegmentationDocument13 pagesConsumer Centered "Brand Value" of Foods: Drivers and SegmentationIvo MarcicPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Research QuarterlyDocument16 pagesBusiness Research QuarterlyAllan AlvesPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter - I 1. Background of The StudyDocument9 pagesChapter - I 1. Background of The StudyS TradersPas encore d'évaluation

- Analisis Keputusan Pembelian Dan Tingkatan Loyalitas Merek Nasional Dan Merek TokoDocument12 pagesAnalisis Keputusan Pembelian Dan Tingkatan Loyalitas Merek Nasional Dan Merek TokoMuhammadAgungPananrangPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer Decision-Making Styles On Domes PDFDocument14 pagesConsumer Decision-Making Styles On Domes PDFAhtisham AhsanPas encore d'évaluation

- A STUDY ON CUSTOMER ATTITUDE TOWARDS COLGATE TOOTHPASTE WITH REFERENCE TO COIMBATORE DISTRICT Ijariie7308 PDFDocument6 pagesA STUDY ON CUSTOMER ATTITUDE TOWARDS COLGATE TOOTHPASTE WITH REFERENCE TO COIMBATORE DISTRICT Ijariie7308 PDFRamana RamanaPas encore d'évaluation

- A STUDY ON CUSTOMER ATTITUDE TOWARDS COLGATE TOOTHPASTE WITH REFERENCE TO COIMBATORE DISTRICT Ijariie7308 PDFDocument6 pagesA STUDY ON CUSTOMER ATTITUDE TOWARDS COLGATE TOOTHPASTE WITH REFERENCE TO COIMBATORE DISTRICT Ijariie7308 PDFzeeshanPas encore d'évaluation

- Stationary MarketsDocument25 pagesStationary MarketsCassia MeroPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Mass Hareeza AliDocument8 pages2 Mass Hareeza AliCh IrfanPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer PerceptionDocument19 pagesConsumer PerceptionAdd KPas encore d'évaluation

- ContentServer With Cover Page v2Document15 pagesContentServer With Cover Page v2Sonam GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijsrmjournal Journalmanager 27 IjsrmDocument8 pagesIjsrmjournal Journalmanager 27 IjsrmhanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Local Competition and Impact of Entry by A DominanDocument40 pagesLocal Competition and Impact of Entry by A DominanDiệu Tiên PhạmPas encore d'évaluation

- The Impacts of Consumers' Need For Uniqueness (CNFU) and Brand Personality On Brand Switching IntentionsDocument12 pagesThe Impacts of Consumers' Need For Uniqueness (CNFU) and Brand Personality On Brand Switching IntentionszordanPas encore d'évaluation

- Local Brands and Global BrandsDocument6 pagesLocal Brands and Global BrandsElan ChezhianPas encore d'évaluation

- Unique Brand Extension ChallengesDocument12 pagesUnique Brand Extension ChallengesDr. Firoze KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Organized Retailing in India-An Empirical Study of Appropriate Formats and Expected TrendsDocument7 pagesOrganized Retailing in India-An Empirical Study of Appropriate Formats and Expected TrendsADHINATH RPas encore d'évaluation

- Shustack Costco CaseDocument25 pagesShustack Costco Caseapi-534406861Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lectura - Capitulo 2 - UnlockedDocument16 pagesLectura - Capitulo 2 - UnlockedMiguel Angel Delgado ArandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Development of Retail FormatsDocument7 pagesDevelopment of Retail FormatsLaxmi KanwarPas encore d'évaluation

- Kodak's Funtime Film Case Analysis and RecommendationDocument7 pagesKodak's Funtime Film Case Analysis and RecommendationShreeraj PawarPas encore d'évaluation

- Nathan Fong JMPDocument33 pagesNathan Fong JMPciriyuzPas encore d'évaluation

- (HANDOUT) Unbeatable Growth Hacking StrategyDocument60 pages(HANDOUT) Unbeatable Growth Hacking StrategyHarnendio Aditia Nugroho0% (1)

- Full Download Retailing Management 9th Edition Michael Levy Test BankDocument35 pagesFull Download Retailing Management 9th Edition Michael Levy Test Bankangilaalomaw100% (35)

- Tetley Brand Valuation Spreadsheets Blank 2022 23Document2 pagesTetley Brand Valuation Spreadsheets Blank 2022 23Kanika SubbaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumers Perception of Private BrandsDocument8 pagesConsumers Perception of Private BrandsmanojrajinmbaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pulse Report-PersonalCare-Q3-2013Document20 pagesPulse Report-PersonalCare-Q3-2013IRIworldwide100% (1)

- Managing Retailing, Wholesaling, and Logistics - Penaflorida PDFDocument12 pagesManaging Retailing, Wholesaling, and Logistics - Penaflorida PDFJacob DyPas encore d'évaluation

- Soap & Cleaning Compound Manufacturing in The US Industry ReportDocument47 pagesSoap & Cleaning Compound Manufacturing in The US Industry ReportStéphane Alexandre100% (1)

- Saranya Project ReportDocument42 pagesSaranya Project ReportParikh RajputPas encore d'évaluation

- Klaus Uhlenbruck - Hochland CaseDocument15 pagesKlaus Uhlenbruck - Hochland CaseAvogadro's ConstantPas encore d'évaluation

- Retail Formats & Theories: 10/6/2017 Retailing Management - Swapna Pradhan 1Document12 pagesRetail Formats & Theories: 10/6/2017 Retailing Management - Swapna Pradhan 1Adarsh KrishnaPas encore d'évaluation

- DMartDocument11 pagesDMartAshwin DholePas encore d'évaluation

- Increase Brannigan Foods Profits with Strategic Marketing PlanDocument20 pagesIncrease Brannigan Foods Profits with Strategic Marketing PlanKashish Narula50% (2)

- Why Retailers Sell More or Less Than Their Fair Share in A CategoryDocument30 pagesWhy Retailers Sell More or Less Than Their Fair Share in A CategoryKetanDhillonPas encore d'évaluation

- BSG QuizDocument7 pagesBSG Quizalitehm100% (2)

- Innovation in RetailingDocument11 pagesInnovation in Retailingliza shoorPas encore d'évaluation

- PFM3 Digital1Document76 pagesPFM3 Digital1luisPas encore d'évaluation

- Case StudyDocument15 pagesCase StudyKelly ChengPas encore d'évaluation

- Koenig Cott AnalysisDocument4 pagesKoenig Cott AnalysisAbaddon LebenPas encore d'évaluation

- A Case Study On BMW Marketing EssayDocument22 pagesA Case Study On BMW Marketing EssayPrince FahadPas encore d'évaluation

- Nestle SA: World's Largest Food and Beverage Company by SalesDocument4 pagesNestle SA: World's Largest Food and Beverage Company by Salesmrken94Pas encore d'évaluation

- Red Bull GMBH in Soft Drinks - World: June 2010Document40 pagesRed Bull GMBH in Soft Drinks - World: June 2010nazeer9999Pas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Strategies For Fast-Moving Consumer GoodsDocument4 pagesMarketing Strategies For Fast-Moving Consumer GoodsKrishna MhatrePas encore d'évaluation

- Snacking Startups 2.0 - CB Insights 2017Document68 pagesSnacking Startups 2.0 - CB Insights 2017jc224100% (1)

- Consumer PerceptionsDocument10 pagesConsumer PerceptionsSyahridzuel Ulquiorra SchifferPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing EnvironmentDocument9 pagesMarketing EnvironmentMega Pop Locker0% (1)