Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Ritual As Action and Symbolic Experession

Transféré par

Rifka RifkaDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Ritual As Action and Symbolic Experession

Transféré par

Rifka RifkaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Ritual as Action and Symbolic Expression

Jesper Srensen

1. Introduction What is ritual? Is ritual a distinct type of action? Or is it more adequately described as a genre, distinct from other genres by certain particularities? Why is it that observers distinguish with relative ease both aesthetic and ritual performances around the globe from other types of human behaviour, and do rituals provoke specific cognitive activities when perceived? These are among the questions I will address in this paper. I will concentrate on ritual as a special modality of human behaviour, as something that we can explore from different angles, and thereby hopefully shed some light on both ritual behaviour itself, and on its relation to other types of human behaviour, in particular aesthetic genres. However, this paper is not an attempt to provide a definition of ritual based on necessary and sufficient conditions, and I very much doubt that such a definition would be possible. Instead, I will outline possible, and I believe fruitful, approaches that can eventually lead to the construction of a prototype theory of ritual and ritualization. A prototype theory does not aim to delineate the exact borders between the categories of ritual and ritualization and neighbouring concepts such as ceremony and habit. Instead, it can propose a number of aspects that can function as prototypical characteristics for the category. It is possible that not all those characteristics need to be present in all instances of the category, and it might turn out that we can find subtypes of ritual or ritualization that share only some of the common characteristics. This concept of ritual resembles the notion of family-resemblance introduced by Wittgenstein to analyse the content of the category of play (itself a category with more than circumstantial interest in the study of both aesthetics and ritual). Before we get to these characteristics, it is useful to present some of the traditional approaches to ritual in anthropology and the study of religion. As

40

JESPER SRENSEN

the area of ritual has been of central importance for more than a century, I will limit myself to a short summarising discussion of two approaches: the intellectualist and the symbolist. The intellectualist approach understands ritual as a type of rational behaviour based on explanatory principles that formally, if not substantially, are indistinguishable from those of Western science. To put it crudely, the intellectualist approach does not distinguish the behaviour of planting from that of chanting if both are backed by explanatory theories arguing for their necessity in some practical endeavour, in this case agriculture. Both are seen as rational instrumental or technical actions in relation to a theoretical background. They are rational as the behaviour can be explained and defended from the theory underlying it. Thus, magical practices in socalled primitive societies are not irrational and nonsensical, but are merely based on flawed theoretical premises.1 In contrast to the intellectualist position, the symbolist approach does not accept that ritual should be seen as instrumental actions based on theoretical presumptions about the world. There is no direct causal connection between underlying beliefs and ritual actions, and chanting should not be understood as motivated by the same type beliefs about the world as is the case with planting. Rituals should instead be understood as expressive behaviour that communicates certain meanings, notably about social structure, coded in symbolic language. Thus, the job of the observer is to acquire the interpretational key necessary in order to decipher the message inherent in this apparently irrational or wrong action.2

1

Representatives of the intellectualist approaches to ritual and religion are E. B. Tylor, Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom (London: John Murray, 1871); J. G. Frazer, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, 3rd edn, 13 vols (London: MacMillan Press Ltd., 191115), I: The Magic Art and the Evolution of Kings (2 vols); I. C. Jarvie and J. Agassi, The Problem of the Rationality of Magic, in British Journal of Sociology, 19 (1967), 5574; J. Agassi and I. C. Jarvie, Magic and Rationality Again, British Journal of Sociology, 24 (1973), 23645; R. Horton, African traditional thought and Western science, in Rationality, ed. by B. Wilson (Oxford: Blackwell Publications, 1970), pp. 13171; J. Skorupski, Symbol and Theory: A Philosophical Study of Theories of Religion in Social Anthropology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976). 2 Representatives of the symbolist approach to ritual and religion are M. Mauss, A General Theory of Magic, trans. by Robert Brain (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972; 1st edn (French) 1902 3); E. Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, trans. by Joseph Ward Swain (New York: Free Press, 1965; 1st edn (French) 1915); J. Beattie, Other Cultures (London: Cohen & West,

RITUAL AS ACTION AND SYMBOLIC EXPRESSION

41

Both positions are problematic as an approach to understand what ritual behaviour is about. The intellectualist claim that rituals are rational actions based on underlying theoretical beliefs has the obvious problem that people often fail to express such beliefs when asked why they perform a specific ritual, and it is doubtful whether such beliefs are entertained as the motivation for any ritual performance. Further, intellectualism cannot explain why people, with alternative explanations available, such as most Westerners, keep participating in ritual actions even when they do not share the purported underlying beliefs at least not as true statements about the world. Other factors than instrumental or technical actions motivated by beliefs must be at stake. The symbolist approach has another problem. As it does not accept the grounds given by the participants for a ritual performance, it faces the obvious problem of deciding between the different interpretational keys used to make sense of the ritual and arguing for the employment of one model in favour of another. Whether a ritual expresses fundamental values of a society, Freudian aspects of the unconscious, or Jungian archetypes cannot be decided by the material at hand, but will be a matter of interpretation. These problems have lead some scholars, such as Frits Staal to propose that rituals have no meaning at all. He argues that both intellectualists and symbolist are wrong in their very premise that rituals should be understood as expressions of either internal theoretical beliefs or unconscious structures or values. Staal argues that rituals are not meant to communicate anything, a proposition based on the extreme difficulty of explaining and agreeing on its meaning, even by skilled participants.3 As I will argue below, I think rituals have very basic structures of meaning, and that these constrain their possible function in a number of ways. Still, I find Staals criticism both necessary and stimulating, as it forces us to look at ritual again, without deciding beforehand what its function is in relation to beliefs or systems of meaning. So in the rest of this paper, I will attempt to present some basic features of ritual action and ritualization in order to explain how these actions provoke certain hermeneutic strategies in participants and observers alike.

1964); J. Beattie, On understanding ritual, in Rationality, ed. by B. Wilson (Oxford: Blackwell Publications, 1970) pp. 24068; V. W. Turner, The ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1969). 3 F. Staal, The meaninglessness of ritual action, Numen, 26 (1979), 222.

42

JESPER SRENSEN

I believe that a good starting point of this investigation is the simple observation that ritual is a type of action. First, as other types of actions, rituals involve bodily movements governed by motor programmes. Ritual participants do something to something or somebody. However, actions are not defined by motor-programmes alone but involve representations of an effect on the world, whether physical or psychological. Prototypical actions have an effect on the world, or we wouldnt recognise them as actions, and similarly, rituals are meant to affect the world, even if it can be discussed whether their effect can be found in the world, in the social structure or in the psychology of the participants. Of course, this question of effect depends crucially on whom you ask and whether you are looking for the insiders/performers or the outsiders/observers representations of ritual effect. Finally, prototypical actions also involve an agent with intentions, whether conscious or unconscious, as this is what distinguishes actions from mere incidents. Thus, a person suffering from Parkinsons disease might topple a glass and thus effect a change in the world, but as this action is explicitly unintentional, it will not be judged as an action but as an incident. However, it is evident that ritual actions in several ways deviate from ordinary actions, and in order to analyse these deviations we need to look closer into how we represent ordinary actions. To do this, I will employ two lines of research, human ethology and, cognitive science as both have substantial contributions to make concerning the unconscious processes underlying perception, recognition and performance of diverse types of actions. Both of these, however, are vast structures of scientific knowledge and as space is limited, the presentation will be rather cursory. Still, I hope that the reader will get a flavour of the possible contribution of this line of research to the study of ritual action.

2. Human Ethology Human ethology is the systematic investigation of human behaviour based on a biological and evolutionary approach. Ethology looks for universals of human action and behaviour, and some of the most important questions asked are in what way universal human behaviour has an adaptive value, that is, how some

RITUAL AS ACTION AND SYMBOLIC EXPRESSION

43

actions can enhance the reproductive fitness of individuals and groups and how certain types of behaviour serve basic biological needs. According to a biological approach, a substantial part of basic human actions are based on adaptations to our evolutionary niche. Behavioural patterns are developed in evolution by a selective pressure on individual phenotypes through their environment leading to the differential reproduction of human genotypes. Certain types of behaviour will enhance the agents reproductive success and thereby effect a relatively larger contribution of genetic material to a given population. Thus, according to this view, a substantial portion of human behaviour has evolved as adaptation to selective pressure and is, as such, innate and genetically encoded. This is, of course, a rather controversial claim, especially in the human and social sciences, and it has been, and still is, heavily debated. I think that the question cannot be whether some aspects of human behaviour are universal and genetically encoded, nor that homo sapiens should be the only animal species without such innate behavioural dispositions. Rather, the fundamental question concerns the extent of this encoding and its interaction with culturally prescribed behavioural repertoires. However, what is of importance in this context is ethologys widespread use of the concepts of ritual and ritualization to explain specific modes of both animal and human behaviour. In ethology, ritualization and ritual mean the process by which action sequences are removed from the functional context, in which they have their evolutionary origin, in order to serve another function, namely that of communication. A classic example is Konrad Lorenz description of the pair-bonding ritual among greylack geese. In order to confirm a bonding, the pair of geese perform in unison the action sequence otherwise used to fight off enemies. However, when the action is used in the bonding ritual, there is no enemy present, and the function is transformed from an aggressive action to that of demonstrating or communicating the bonds between the pair.4 This actually comes pretty close to the more or less derogatory understanding of the concept of ritual found in several natural languages, as when something is reduced to pure ritual, implying that the action referred to is devoid of both its

K. Lorenz, Evolution of Ritualization in the Biological and Cultural Spheres, in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 251 (1966), 247526, see also W. Burkert, Structure and History of Ancient Greek Mythology and Ritual (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), Ch. 2: The Persistence of Ritual pp. 3558, 15868.

4

44

JESPER SRENSEN

original function and meaning. Human rituals, both secular and religious, are of course filled with such actions removed from their original function. Bread and wine is consumed in a situation and quantity removing it from all ordinary expectations related to eating and drinking, and stipulated and choreographed aggressive behaviour is used to strengthen group cohesion, to mention but a few examples. An obvious objection against this from the viewpoint of the study of religion, theology, and anthropology would be that the definition is too broad and covers far too many instances. It risks covering most human interaction usually described as communication.5 However in a prototype approach, this need not concern us too much in the initial phase, as we are allowed to extract fundamental aspects in this broad sense of ritual and ritualization and see whether it also covers the actions performed in a more strict sense of the term. I believe this is a particular fruitful approach in attempts to study crossover phenomena such as that between ritual and aesthetics. It is probably unnecessary to say that I think this notion of the transformation of functional action into demonstration and communication, is a likely candidate for a list of prototypical characteristics of ritual action. This is not only because we find these transformations in most human rituals, but also because the communicative and demonstrative actions referred to function on a very basic level of sign exchange, most of which is unconsciously perceived and acted upon. The immense collection of data from a broad spectrum of human societies gathered by the German ethologist Irenus Eibl-Eibesfeldt and his colleagues points to a basic and universal level of human behaviour that functions as a method of communication in almost all aspects of human interaction.6 In a similar manner, Paul Ekman has described how certain facial expression are cross-culturally recognised as expressing fundamental or basic emotions.7 Ethology thus claims that humans, as biological beings, have a fundamental grammar of expression that works independently from cultural

5 The dismissive attitude towards the notion of ritualization in human ethology is exemplified by anthropologist E. Leach, Ritualization in Man in Relation to Conceptual and Social Development, in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 251 (1966), 403408. 6 I. Eibl-Eibesfeldt, Human Ethology (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1989). 7 P. Ekman, Cross-cultural studies of facial expressions, in Darwin and Facial Expressions, ed. by P. Ekman (New York and London: Academic Press, 1973).

RITUAL AS ACTION AND SYMBOLIC EXPRESSION

45

symbolic systems and directly influences the unconscious mental processing of social interaction. What is important in this context is not so much the fact that these types of communicative actions are themselves ritualized behaviours, but rather that these forms of signalling are further exaggerated in the stricter forms of rituals, for instance in religious rituals. Thus, rituals and ritualization in a stricter sense can often be recognised by the exaggeration of ordinary patterns of behaviour, and this exaggeration is formed on top of the basic meaning structure. Rituals combine evolutionary grounded meaning with culturally developed symbolic structures. Another important insight from ethology is that ritualization together with play entails a process of weakening or decoupling of the emotions involved in the actions. Mammals have the ability of pretend play, where actions are performed without full emotional investment and with greater degree of intentional control. Similarly, ritualized behaviour deciding rank in a social group entails a smaller emotional investment than direct physical confrontation. This weakening of emotional intensity might seem strange, as the common apprehension of rituals is that they in fact produce intense emotions in participants. Thus, Durkheim argues that rituals provoke a feeling of collective effervescence.8 The contradiction is only apparent: as the ethological argument contrasts the emotional intensity of ritualized action with the real and nonritualized action, whereas the anthropological argument contrasts the emotions evoked by the performance of ritual to no actions at all. Thus, ritualized warfare will have a lower emotional intensity than real warfare but a higher one than no action at all. A further development is the ability to perform actions at spatio-temporal distance from their functional context, and in humans to run mental simulations of actions without involving any motor activity. This has the extremely important entailment that it forms the evolutionary pre-adaptation for the development of symbolic communication by means of language. Thus, ritual can be seen as a bridgehead leading from biologically based signalling, locked in a set referential space and dependent on spatial contiguity, to cultural symbolic systems able to convey meaning through reference to other symbols

E. Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (New York: Free Press, 1965).

46

JESPER SRENSEN

and relatively independent on time and place.9 At the same time it entails that symbolic expression, because of its connection to universal behaviour patterns, does exhibit some of the emotional characteristics found in the actions it transposes. Language is inherently affective, even if less so than other more biologically basic types of communication. If we should summarise the aforementioned, we could say that ethology tells us that ritualization consists in the transformation of functional behaviour into demonstration or communication; that a substantial part of this communication is universal and based on innate and unconscious expressions and responses; that ritualization entails a weakening of emotions and a decoupling from immediate functions that enable the development of symbolic communication; and that rituals consist in a mix between universal and biologically fixed expressions and cultural symbols.

3. Cognition The human ability to run mental simulations of actions takes us to the cognitive aspects of ritual actions. Cognitive research has shed light on a whole range of parameters that guide our everyday interaction with the world without coming into conscious attention. An important aspect of this backstage cognition is what cognitive psychologists refer to as domain-specific cognition.10 Contrary to older developmentalist views (e.g. those of J. Piaget), all human cognitive development is no longer thought to depend on the unfolding of a general-purpose learning and processing programme. We do not learn and process information from all realms of the world in the same way, using the same cognitive processes. Instead we seek out specific types of information and we entertain specific expectations to these different domains of experience. Broad ontological categories such as physical or inanimate objects, living kind, animal, intentional agent, and artefact are used, not only to

T. Deacon, The Symbolic Species: The Co-Evolution of Language and the Human Brain (London: Penguin Books, 1997). 10 For an anthology discussing theories of domain-specificity in relation to the study of culture, see Mapping the Mind: Domain Specificity In Cognition and Culture, ed. by L. A. Hirschfeldt and S. Gelman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

RITUAL AS ACTION AND SYMBOLIC EXPRESSION

47

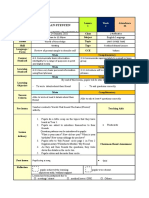

consciously order the world into definable categories, but also to function as unconscious templates guiding expectations to events and actions. Thus, if I throw a ball towards a goal, I will have whole range of expectations concerning preconditions and effects of the action, including how the ball can interact with the surrounding world and other persons. This might sound trivial, but computer sciences attempt to model such behaviour has told us that behind the simple task of throwing a ball towards a perceived goal lies an immense knowledge structure, unconsciously utilised during the task. The basic recognition of something as a ball enables me to use the correct fundamental motor-programmes. Without my conscious control these programmes direct my muscles in the appropriate manner and employ an estimated amount of force in order to achieve the desired speed and direction of the ball. Of similar importance in this context are all the representations precluded by the unconscious categorisation of the ball as an inanimate artefact. If I fail to hit my goal I will not believe that the ball was able to change its direction by its own will, neither will I believe that it entertained any intentions of not hitting the goal in order to disappoint me. Instead, I can attempt to practice my motorprogrammes through a feedback loop between perception and result and thereby improve my overall performance. This improvement points to the intentional characteristics of ordinary actions. Not only do we have intentions concerning results of actions performed, in this case scoring a goal; this intention determines all the inherent actions. In order to throw the ball into the goal, I need to pick it up, I need to aim it, and I need to use a certain amount of energy all actions guided by my overarching intention, even though the specific mental programmes controlling the execution of specific sensory-motor programmes are unconscious. And if I fail, I can attempt to adjust some of these inherent actions in order to achieve my objective. So from a cognitive viewpoint, an action is a representational unit that contains strong links between precondition, action, and effect both in the form of domain-specific causal expectations and the intentional determination of all inherent actions. Combining this with insights from ethology, I have constructed a simplified model of human action (figure 1). Diagnosis and prognosis are the cognitive processes used to link an action with its conditions and its effect. These are represented in Box 1 and consist in

48

JESPER SRENSEN

domain-specific categorisation and related expectations, causal intuitions, and a strong drive to detect agency in actions. These are combined with perceptual clues based on relations of contiguity and similarity, and communicative behaviours developed in the course of evolution, represented in Box 2.

Figure 1: Representations of ordinary actions But what does that tell us about ritual in a stricter sense? Rituals systematically alter representations of both intentional and domain-specific aspects of an action. As argued by anthropologists Humphrey and Laidlaw, the relation between the intention of the actor and the actions performed is radically transformed. In a ritual action, the intentions are strictly related to the performance of the whole action sequence contained in the ritual, but they are

RITUAL AS ACTION AND SYMBOLIC EXPRESSION

49

not directly related to the individual actions that the ritual consists in.11 I can intend to perform a given ritual, and even have a certain goal in mind, but I cannot change any of the stipulated actions of which the ritual consists and still perform the ritual. Thus, if a ritual fails to achieve its desired result, I cannot go back and change certain parameters, as is the case in non-ritual actions (provided I have the practical competence, of course). A ritual is exactly defined as containing a number of stipulated entities, whether this stipulation concerns the action itself, the agent, or objects utilised. Using the concepts of philosopher John Searle, ritual actions are based on conditional rules. One cannot change its constitutive elements and still perform the ritual, just as one cannot change the rules of chess, and still be playing chess.12 The transformation of the relation between the intentions of the performing agent and the stipulated ritual actions involved provokes a cognitive search for what I have elsewhere referred to as the magical agency of ritual actions. This is the ritual entity represented as guaranteeing the efficacy of the ritual, or in the terminology of Searle, its conditional aspects, i.e. those aspects that cannot be changed if the ritual is to have any efficacy. Magical agency can be invested in different aspects of the ritual. Sometimes it is in the ritual performer, sometimes in the actions performed, and sometimes in objects utilised.13 What is of importance is the fact that the conditional character of ritual actions can provoke a cognitive search for the instance responsible for the ritual form that guaranties the efficacy of the ritual. Rituals also tend to bypass domain-specific expectations governing the relation between the condition, the action, and its purported effect. This is especially the case with so-called magical rituals, where the effect should be following more or less directly after the performance of the ritual, but I believe this feature covers most types of religious rituals. One of the prototypical characteristics of ritual actions is Precisely the opaque causal relation between conditional space, the action space, and purported effect space it is almost

11

C. Humphrey and J. Laidlaw, The Archetypal Actions of Ritual: A Theory of Ritual Illustrated by the Jain Rite of Worship (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994). 12 J. R. Searle, Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language (Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 1969). 13 J. Srensen, Essence, Schema, and Ritual Action: Towards a Cognitive Theory of Magic (unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Aarhus, 2000).

50

JESPER SRENSEN

impossible to entertain strong intuitions about the result of the concrete actions performed in the ritual. By removing actions, agents, and objects from their ordinary functional domains, domain-specific expectations are bypassed or, in some cases even violated, and this entails that other modes of ascribing meaning and purpose to the actions are utilised.14 When the bread and wine used in the Eucharist obviously do not serve to satisfy hunger and thirst, some other reason must inscribe meaning into the actions performed. Thus, bypassing domain-specific expectations prompts a search for other instances that can convey meaning or purpose to the action performed. Two major strategies can be observed. The first consists in exploiting directly perceptual clues found in the ritual action. In what is usually referred to as magical rituals, this hermeneutic approach utilises basic aspects of similarity and contact/contiguity. Thus, the British anthropologist Evans-Pritchard describes how the Azande ritually treat leprosy by employing a specific plant, a creeper, with the perceptual characteristics that it sheds small branches, like a person suffering from leprosy looses his outer extremities. The plant does it as part of a cycle of renewal, and the ritual aims to transfer this property to the person suffering from leprosy.15 In this case, the focus is on the ritual efficacy, and in the place of strong, domain-specific relations, weak perceptual clues are used to establish a causal relation linking condition, action, and result.16 Of course, a conventional or symbolic relation primes the connection between the creeper and the disease thereby limiting the almost endless number of possible perceptual connections, but even so, the invention of this ritual cure against leprosy is motivated by the perceptual similarity, and this non-arbitrary, perceptible basis is possibly revived whenever the ritual is performed. The second hermeneutic strategy consists in developing more or less established symbolic interpretations relating the ritual action to its conditions and its purported effect. Thus, established dogmatic systems and theologies

For a theory of religious ideas as based on violations of domain-specific principles, see P. Boyer, The Naturalness of Religious Ideas: A Cognitive Theory of Religion (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1994). 15 E. E. Evans-Pritchard, Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic among the Azande (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1937). 16 This is inspired by H. Kummers notion of weak causation, H. Kummer, Causal knowledge in animals, in Causal Cognition: A Multidisciplinary Debate, ed. by D. Sperber, D. Premack, and A.J. Premack (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995).

14

RITUAL AS ACTION AND SYMBOLIC EXPRESSION

51

often devote a great deal of attention to explaining why and in what manner a ritual works, and what conditions should be upheld for it to be a genuine expression of a specific ritual. In the most extreme cases, this symbolic interpretation will deny the ritual any real or magical effect, and only see it as a symbolic expression of an underlying system of beliefs. I believe this is one of the effects of the Protestant reformation of ritual practices. Such symbolic focus will, however, tend to undermine the ritual structure, as it will run counter to the basic intuitions involved in representations of ritual actions as being precisely actions, wherefore religious traditions can be understood as driven by a dynamic interaction between ritual action and symbolic interpretations. It is important to notice that symbolic interpretations need not reflect established theologies but can be more or less idiosyncratic interpretations relating the action to some explanatory frame. We thus find a continuum from established dogmas to idiosyncratic interpretations, and an important function of established religious institutions is to define the correct symbolic interpretation(s) in order to avoid competing interpretations that could destabilise institutional authority. It is important for me to emphasise that even though rituals, in their very form, can direct attention to one or another of these hermeneutic strategies, in itself a ritual action can evoke both. There are no magical rituals, only magical interpretation and usage of ritual action. The magical interpretation points towards the efficacy of the action performed, downplaying or even deconstructing the symbolic meaning inherent in ritual elements. An example of this is the widespread use of nonsense words like abracadabra or words that have lost their original meaning such as hocus-pocus. On the other hand, symbolic interpretations embed ritual action in more comprehensive symbolic systems, and thereby tend to downplay the importance of perceptual clues or crystallise their interpretation. However, what I want to emphasise here is that the very process of ritualization tends to make symbolic interpretations highly unstable. First, because only weak perceptual clues (in contrast to domainspecific reasoning) supply any basic meaning to the ritual action, and second, because symbolic elements utilised in the ritual, such as language, are ritualised themselves and are thereby removed from their ordinary context, in this case that of symbolic communication. I shall return to this below.

52

JESPER SRENSEN

If we apply the discussion of rituals from ethology and cognitive science to the model of action, we find two major transformations. First, there is a tendency to invest importance in the biologically evolved communicative aspects of actions and directly perceptible features of the actions, such as spatial contiguity and similarity. Second, we find a new interpretational strategy using symbolic interpretations, whether culturally specified or idiosyncratic.

Figure 2

RITUAL AS ACTION AND SYMBOLIC EXPRESSION

53

As domain-specific relations are bypassed, the relative importance of direct perceptual clues is emphasised, as they supply a fairly easy access to a basic meaning of the ritual action. Ritualization in the broad sense of the term involving basic physical communication can be understood in this light, as a search for perceptual features of information in lack of a direct functional element in the actions performed. Ritual hereby functions as a bridgehead to symbolic communication. This human ability to produce symbolic interpretations of ritual action facilitates its embedding in a wider context of meaning, consisting of other communicative actions, narratives, and other meaningful cultural constructs. The symbolic interpretations are only loosely constrained by the perceptual clues, and they tend to be attached to already existing cultural models and systems. However, as the interpretations are underdetermined by the actions performed as rituals are semantically ambivalent they tend to be very unstable and subject to constant criticism and competition from rival interpretations. Thus, on the one hand, rituals provoke symbolic interpretations, but on the other hand, they suply only a weak grounding for the interpretations and de-symbolise the elements used. Rituals are therefore sources of both continuous construction of new meaning through symbolic interpretation and sources of constant deconstruction of already established meaning.

4. Concluding remarks Does this tell us anything about the relation between ritual action and aesthetic genres? I believe so on several counts. First, the common function of emotional and contextual decoupling or detachment found by ethology in both ritual and play might point to the fact that aesthetic genres such as drama have several origins. Thus, it cannot be certified that aesthetic genres such as theatre or music have their historical origin in ritual, but rather that the ability to ritualize behaviour facilitates a distancing between action and function common to aesthetics and ritual alike. Second, universal human behaviour apparently underlies and interacts with cultural expressions in both rituals and aesthetics. Both rituals and aesthetics can thus be seen as cultural extensions and elaborations of a basic register of human behaviour that supplies basic patterns

54

JESPER SRENSEN

of meaning.17 Third, and most importantly in this context, aesthetics, like ritual, seem to function by the constant deconstruction of established symbolic and cultural meaning in order to reach out for these basic human meaning patterns that subsequently give rise to symbolic interpretations that will themselves be deconstructed and so on Thus, aesthetics and rituals can potentially serve the function of rejuvenating cultural structures, not because they contain symbolic meaning themselves, but rather because they dismantle conventional symbolic meaning and thereby facilitate the construction of new symbolic interpretations in a specific socio-cultural context. This common structure can give rise to speculations and investigations into the historical relation between ritual and aesthetic genres, both on a general and a specific level, and it will, at least, explain why ritual elements are so easily transposed from the ritual to the aesthetic genres.

For an example of the role of facial expressions in ritual performance, see R. Schechner, Magnitudes of Performance, in By Means of Performance: Intercultural studies of Theatre and Ritual, ed. by R. Schechner and W. Appel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

17

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- 3.2.1 Nepal National Chapter Report and Future PlansDocument8 pages3.2.1 Nepal National Chapter Report and Future PlansRifka RifkaPas encore d'évaluation

- Greenhouse 2015 Conference Student Scholarships Information SheetDocument2 pagesGreenhouse 2015 Conference Student Scholarships Information SheetRifka RifkaPas encore d'évaluation

- Secure Rice Production in North SumatraDocument18 pagesSecure Rice Production in North SumatraRifka RifkaPas encore d'évaluation

- PIR EssayTutorial and Referencing GuideDocument27 pagesPIR EssayTutorial and Referencing GuideRifka RifkaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tesla CatalogDocument28 pagesTesla CatalogRifka RifkaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Forced-Choice Paradigm and The Perception of Facial Expressions of EmotionDocument11 pagesThe Forced-Choice Paradigm and The Perception of Facial Expressions of EmotionjnkjnPas encore d'évaluation

- Interactive FOR Media Information LiteracyDocument7 pagesInteractive FOR Media Information LiteracyJoel Cabusao Lacay100% (1)

- Oxford Happiness QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesOxford Happiness QuestionnaireSyed Wasi ShahPas encore d'évaluation

- Attitudes, Values & EthicsDocument21 pagesAttitudes, Values & EthicsRia Tiglao FortugalizaPas encore d'évaluation

- Getting Motivated To Change: TCU Mapping-Enhanced Counseling Manuals For Adaptive TreatmentDocument63 pagesGetting Motivated To Change: TCU Mapping-Enhanced Counseling Manuals For Adaptive TreatmentprabhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 2 The Development of EspDocument4 pagesChapter 2 The Development of EspK wong100% (1)

- The Tree of Life: Universal Gnostic FellowshipDocument5 pagesThe Tree of Life: Universal Gnostic FellowshipincognitoPas encore d'évaluation

- Lotf Argument EssayDocument4 pagesLotf Argument Essayapi-332982124Pas encore d'évaluation

- Behavior Specific Praise Statements HandoutDocument3 pagesBehavior Specific Praise Statements HandoutDaniel BernalPas encore d'évaluation

- Elyse Gementiza - Task 6Document4 pagesElyse Gementiza - Task 6Sean Lester S. Nombrado100% (1)

- Tausk Influencing MachineDocument23 pagesTausk Influencing MachineMarie-Michelle DeschampsPas encore d'évaluation

- Distinguish Between IRS and DBMS and DMDocument3 pagesDistinguish Between IRS and DBMS and DMprashanth_17883100% (2)

- Course Outline Accounting ResearchDocument12 pagesCourse Outline Accounting Researchapi-226306965Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Document Reality PDFDocument3 pages2 Document Reality PDFNicole TapiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Health Promotion Reflection - AdvocacyDocument2 pagesHealth Promotion Reflection - Advocacyapi-242256654Pas encore d'évaluation

- ch3Document43 pagesch3Sudheer AyazPas encore d'évaluation

- Civic English Form 4 & 5 2019Document6 pagesCivic English Form 4 & 5 2019Norfiza Binti Abidin100% (3)

- IELTS Speaking and Writing: Lesson PlanDocument14 pagesIELTS Speaking and Writing: Lesson PlanNandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Simple Present TenseDocument9 pagesSimple Present TenseSurya Chakradhara PosinaPas encore d'évaluation

- CEE471 SyllabusDocument2 pagesCEE471 SyllabusSuhail ShethPas encore d'évaluation

- Personal & Professional Development Plan PDFDocument16 pagesPersonal & Professional Development Plan PDFElina Nang88% (8)

- Sec 2 Movie Review Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesSec 2 Movie Review Lesson Planapi-332062502Pas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 1Document152 pagesUnit 1Crazy DPS YTPas encore d'évaluation

- LOCUS of CONTROL PresentationDocument17 pagesLOCUS of CONTROL PresentationAditi Ameya Kirtane100% (1)

- Lesson Plan 7 - Adverbs of FrequencyDocument4 pagesLesson Plan 7 - Adverbs of FrequencyMaribel Carvajal RiosPas encore d'évaluation

- Free Time Unit 5Document26 pagesFree Time Unit 5Jammunaa RajendranPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching Guide For Critical Approaches in Teaching Philippine LiteratureDocument7 pagesTeaching Guide For Critical Approaches in Teaching Philippine LiteratureMaria Zarah MenesesPas encore d'évaluation

- Young Explorers 3: Diem PhamDocument42 pagesYoung Explorers 3: Diem Phamcloud rainyPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 5 - NotesDocument11 pagesUnit 5 - NotesBhavna SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Importance of Accurate Modeling Input and Assumptions in 3D Finite Element Analysis of Tall BuildingsDocument6 pagesImportance of Accurate Modeling Input and Assumptions in 3D Finite Element Analysis of Tall BuildingsMohamedPas encore d'évaluation