Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Language Differences and Communication (Contrastive Analysis Revisited)

Transféré par

Hendrik Lin Han XiangDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Language Differences and Communication (Contrastive Analysis Revisited)

Transféré par

Hendrik Lin Han XiangDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Page 1 of 4

Language differences and communication: Contrastive analysis revisited

Lanlin Zhang Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Education The University of Western Ontario lzhang28@uwo.ca In the past, proponents of Comparative Analysis (CA) claimed that CA could predict and describe the patterns that would cause difficulty in learning, and those that would not cause difficulty, by systematically comparing the language and culture to be learned with the native language and culture of the student (Lado 1957). This claim was shaken in the 1960s by Noam Chomskys (1968) Universal Grammar (UG) hypothesis. By the 1980s, comparative analysis was considered to be very superficial and of little or no help at all in the learning task (Wardhaugh 1983). However, even at a time when almost everyone seems to be talking about communicative language learning and teaching, it is my belief that revisiting CA can provide fresh insights into research and practice in the exploration of what the so-called interlanguage competence (Gass & Selinker 1994) entails. The present study utilizes two case studies to support this belief. Stories of two Chinese EFL (English as a foreign language) students in a Canadian institution of higher education will be presented to illustrate the validity and rationale for my belief in the value of CA. The article concludes by arguing that contrastive analysis of Chinese and English will shed light on understanding how communicative competence can be developed by Chinese learners of English as a second language (ESL). Keywords : communication, contrastive analysis, Chinese students, language interference, code-switching Introduction How people learn to communicate in a second language has been an intriguing question that has sparked the interest of language learners, educators, and researchers for centuries. A multiplicity of theories have vied to explain the relationship between the learners first language (L1) and second language (L2). For example, the grammar translation method, which prevailed in Europe in the 19th century, employed the learners L1 extensively by explaining the words and structures of foreign language in terms of the learners native language. The ascendancy of the audio-lingual method in the 1960s as a reaction to the grammar-translation method was accompanied by a view of the foreign language learning as basically a mechanical process of habit formation (Rivers, 1968, p. 325). The audio-lingual method was, to a large extent, based on a theory of language learning that held that all languages are different, and should be taught differently. Communicative language teaching (CLT) focuses on the usage of authentic materials to foster an L2 learners grammatical, discourse, strategic, and social-cultural competence with little if any mention of L1 skills (Savignon 2001). Contrastive analysis, a comparative analysis of two languages including their similarities and their differences was thought by many in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s to be a useful predictor of where second language students would likely encounter problems in learning a second language. It stood to reason that if certain elements of a second language differed greatly from a students native language, the student would likely encounter difficulties with those elements. This hypothesis later drew criticism from many researchers who argued that L1 skills are useful to second language acquisition in a process called language transfer (Gass & Selinker, 1994; OMalley and Chamot, 1990; Faerch and Kasper, 1987 etc.). Language transfer causes a learner to project features of his L1 onto his L2. OMalley and Chamot (1990) define transfer as the use of previous linguistic or prior skills to assist comprehension or production (p. 120). Rather than focusing on structural differences between L1 and L2, more recently researchers have focused on the process and interlocutors involved in the interactions between L1 and L2. Berthold et al. (1997), for example, used the term interference to refer to the transference of elements of one language to another at various levels (e.g., phonological, grammatical, and orthographic levels). They define phonological interference as foreign accents stemming from stress, rhyme, intonation and speech sounds from the L1 that influences the L2. Grammatical interference is defined as the L1 influencing the L2 in terms of word order, use of pronouns and determinants, tense, and mood. Interference at a lexical level provides for the borrowing of words from one language and converting them so they sound more natural in the other language and orthographic interference includes the spelling of one language altering another. Meanwhile, researchers such as Cook (1991), Crystal (1987), Milroy (1987) used the term code switching to refer to the switching between L1 and L2 due to the inability to express oneself in one language. Code switching occurs when a speaker needs to compensate for some difficulty, to express solidarity, to convey an attitude or to show social respect (Crystal, 1987; Berthold, Mangubhai, & Bartorowicz, 1997). All these theories are based on the premises that: (a) L1 and L2 are structurally different, (b) language learners have to be aware of structural differences between L1 and L2, and (c) the structural differences serve as foundations for differentiated communication needs. Whether structural differences are perceived as the basis for language transfer, language interference, or code-switching, they serve the purpose of understanding and improving communication between the L2 learners and the target language speakers. Whether L1 skills facilitate or impede the development of L2 skills, my argument in this essay is that a comparison of the structural differences between L1 and L2 provides insights into how L2 speakers communicate successfully and/or unsuccessfully in different situations. It is also possible that the dichotomous views of the L1 as being either positive or negative could be reevaluated and viewed from a new perspective. What draws me to revisiting the CAH (contrastive analysis hypothesis) is partly my personal experience as an ESL (English as a second language) learner, educator, and researcher, and partly the results of a recent study that I conducted exploring the oral communication skills demonstrated by Chinese students in Canada. The subjects replies to my research questions prompted me to realize that comparative analysis of Chinese and English can help researchers better understand why some Chinese ESL speakers speak in seemingly funny ways. In my opinion, this sensitization will be conducive to better communication between Chinese ESL speakers and native speakers. Improved communication would also assist Chinese and other ESL learners achieve greater academic success and successfully acculturate. In this essay, a brief introduction of CAH will be presented, followed by a contrastive analysis of Chinese and English. Some pertinent findings from my study will then be presented to support my position. Discussion will follow, including suggestions for further research. Contrastive analysis: past and present A systematic comparative study analyzing component wise the differences and similarities between an L1 and L2 was established towards the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, especially in Europe (e.g., Grandgent, 1928; Vietor, 1894; Passy, 1912). Fries (1945), for example, argues that: The most efficient materials are those that are based upon a scientific description of the language to be learned, carefully compared with a parallel description of the native language of the learner (p. 9). Whorf (1941) first employed the term contrastive analysis to denote a comparative study of L1 and L2 which emphasizes linguistic differences. Fisiak (1981) defines comparative linguistics as a subdiscipline of linguistics concerned with the comparison of two or more languages or subsystems of languages in order to determine both the differences and similarities between them (p. 1). The publication of Lados Linguistics Across Cultures (1957) marks the real beginning of modern applied contrastive linguistics. In Lados book, he claims that we can predict and describe the patterns that will cause difficulty in learning, and those that will not cause difficulty, by comparing systematically the language and culture to be learned with the native language and culture of the student (p. vii). Wardhaugh (1970) later termed this claim as the Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis (CAH). For purposes of this essay, the terms contrastive analysis, contrastive linguistics, and contrastive analysis hypothesis will be used interchangeably. More recently, Stockwell and Bowen (1965) have asserted that there exists a hierarchy of difficulty of learning problems based on types of differences between languages. They argue that the greater the difference between languages, where difference is defined in terms of the relative freedom of choice a speaker has in specified contexts, the more persistent the predicted errors will be. Contrastive analysis researchers believe that CAH is useful when it entails adequately describing the sound and grammatical structure of two languages, with comparative statements, giving due emphasis to compatible items in the two systems. It is assumed that learning a second language is facilitated whenever there are similarities between that language (the L2) and the mother tongue (the L1). Learning may be interfered with when there are marked contrasts between the L1 and the L2 (Nickel, 1971). Contrastive analysis emphasizes L1 influence on L2 learning at the phonological, morphological, and syntactic levels. Contrastive analysis is also thought to be instrumental in studies involving machine translation and linguistic typology. However, contrastive analysis has been developing with different voices. Its claim to predictive value (i.e., identifying) learning difficulties is especially challenged by researchers such as Wardhaugh (1970) who argues that: All natural languages have a great deal in common so that anyone who has learned one language already knows a great deal about any other language he must learn. Not only does he know a great deal about the other language even before he begins to learn it, but the deep structures of both languages are very much alike, so that the actual differences between the two languages are really quite superficial (p. 11). Wardhaugh (1970) concludes that contrastive analysis can be of little or no help at all in the learning task (p. 11). Earlier still, researchers such as Selinker (1972), Richards (1974), and Tran (1975) also identified errors which were of a non-contrastive origin, thereby lowering expectations of CAH as a predictor of language error. Later on, error analysis (EA) arose as a counter-theory to CAH later on which treated second language errors as similar to errors encountered in first language acquisition. These errors are believed (Richards, 1971) to be divided into three sub-categories: overgeneralization, incomplete rule application, and hypothesizing based on

http://www.uwo.ca/sogs/WJGR/2005/WJGR2005_v12_p113_Zhang.htm

03/05/2012

Page 2 of 4

false concepts. The debate raged on between CA and EA through the 1970s. EA suffered notably from Schacters (1974) study which showed error analysis misdiagnoses of student learning problems because learners frequently avoided certain difficult L2 elements. Today both CA and EA are rarely used in identifying problem areas for L2 learners. An exception is Pierson (1982) who uses error analysis as a basis for developing curriculum items for Cantonese (a Chinese dialect) speakers. The CA versus ES debate has virtually disappeared over the last 10 years. Most researchers agree that neither CA nor EA alone can predict or account for the myriad of errors encountered in learner English. However, as Schackne (2002) argues, contrastive analysis between English and Mandarin Chinese is still very persuasive. He illustrated some pattern sentences that are structurally sound, but semantically awkward when directly translated into English (i.e., they render the English sentences awkward if not ungrammatical). The superimposition of Mandarin Chinese structure onto English strongly hints of L1 interference. An interesting study was conducted by Davis (2002) of the Hong Kong University of Sciences and Technology. Her findings suggest that teachers who are aware of a few of the grammatical differences between English and Chinese can help students trouble-shoot grammatical hot spots and minimize errors through proof-reading. Grammatical accuracy in English requires much more tweaking than it does in Chinese. For example, because Chinese is a non-inflectional language, tenses and person changes in English are difficult for some students to understand learn. This author has been an L2 learner, teacher, and researcher for many years. Experience and intuition tell me that contrastive analysis of the phonological, grammatical, and lexical difference between Chinese and English can be very useful for L2 learners to pinpoint potential learning difficulties and to better improve the communicative skills so they can be successful in their academic study and life. This kind of analysis also facilitates the development of communicative language teaching materials targeting Chinese EFL (English as a foreign language) learners and practitioners. This section has reviewed issues and individuals involved in the development of contrastive analysis and the different voices in the process. The coming section compares phonological, grammatical, and lexical differences between English and Chinese. Structural differences between English and Chinese The Chinese language belongs to the Sino-Tibetan language family. The Sinitic part of the name refers to various Chinese languages. According to Crystal (1987), Sinitic languages are spoken by over 1000 million people and are the worlds most numerically spoken language. The vast majority of its speakers reside in mainland China (over 980 million) and Taiwan (19 million). Substantial numbers are also found throughout the world, especially Southeast Asia and North America. The word Chinese is often used to describe the people who share a similar writing system (Chinese characters) and a similar cultural background, rather than to describe a spoken form of language. There is great variety among the Sinitic languages spoken by people in different parts of China. As Crystal (1987) claims, the dialects are as different from each other (mainly in pronunciation and vocabulary) as are French or Spanish is from Italian (p. 312). More than 80 languages, and hundreds of dialects, are spoken in China. The Chinese language referred to in my discussion is Putonghua, a hybrid of linguistic units embodying the pronunciation of the Beijing dialect, the grammar of the Northern Vernacular, and the vocabulary of colloquial Chinese literature. This variety was chosen as the national standard and widely promulgated after the establishment of the Peoples Republic of China in 1949. (In Taiwan it is called Guo Yu, or national language. Overseas, it is called Mandarin). A language policy recognizing Putonghua as the medium of instruction in Chinese schools came into effect in 1956 and legally all educational institutions and public service agencies are required to reflect this policy (Zhang, 2002; Zhou, 2002). It is now the most widely used form of spoken Chinese, and is the norm for almost all written publications (Zhou, 2002). The written form of the Chinese language is pictographic and ideographic. This explains the number of varieties of pronunciation in different regions. It also makes it virtually impossible to communicate with the alphabetical world (at least this was what motivated many scholars in the past century or two to establish an alphabetical system to bridge the structural differences). Efforts have been made to Romanize the language since the 19th century with the help of westerners. In 1859, Sir Thomas Wade introduced a language form to China and this was further developed by his successor Herbert Giles (Crystal, 1987). The Wade-Giles system became familiar to western eyes and their effort became the de facto standard for the romanization of Mandarin Chinese for the majority of the 20th century. Other systems such as Gwoyeu romatzyh and the Yale system were suggested later on but the Pinyin system has been the dominant system in China since 1956. Pinyin uses a 58symbol Roman alphabet writing system. The main aim of Pinyin is to facilitate the spread of Putonghua and the learning of Chinese characters. The phonological, grammatical, and lexical difference between Chinese and English outlined next are based on the Putonghua form of the Chinese language and English. Given the fact that the audiences of this essay consists of mainly English speakers, my focus will be on those features of Chinese that the English does not possess. Phonological differences The Chinese language is monosyllabic, and words or phrases are made up of different monosyllabic characters. Each character is usually made up of an initial consonant (called a Shengmu) and a simple or compound vowel (called a Yunmu). Sometimes, a Yunmu can end with a terminal n or ng. The following is a comparison of consonants in Chinese and English, and a comparison of vowels in the two languages. International Phonetic Alphabet is utilized for the comparison. Table 1 and Table 2 illustrates that in comparison with English vowels and consonants, the phonemes //, /e/,/an/, and /n/;/zh/,/ch/, /sh/; and /z/, /c/, never appear in English, and the /v/ sound never appears in Chinese. The difference between /s/ and //; /z/ and // is quite a challenge for Chinese learners of English. They may use sin for thin. Therefore, they would find it hard to distinguish thesis and CSIS. Confusion also occurs when some Chinese speakers try to pronounce right/light. Table 1. Consonants comparison in Chinese and English Chinese English /b/ /p/ /m/ /f/ /d/ /t/ /n/ /l/ /g/ /k/ /h/ /j/ /p/ /b/ /t/ /d/ /k/ /g/ /t/ // /f/ /v/ /s/ /z/ /q/ /x/ /z/ /h/ /c/ /h/ /s/ /h/ /r/ /z/ /c/ /s/ // // /h/ /m/ /n/ /t/ /l/ // /x/ /r/ /j/ /w/

Since there are no consonant blends in the Chinese national language, it is difficult for Chinese speakers to make the double and triple consonant blends common to English. Chinese learners of English may use Chinese sounds when speaking English if the sounds are phonetically similar in the two languages, such as /i/ and /i ./For example, they may pronounce sheep as ship. That is, the differing vowel systems may cause as much confusion as the consonant blends. Table 2. Vowels comparison in Chinese and English Chinese /a/ /o/ /e/ /ai/ /ei/ /ao/ /ou/ /an/ /en/ /ang/ /eng/ /ong/ /i/ /ia/ /ie/ /iao/ /iou/ /ian/ /in/ /iang/ /ing/ /iong/ /u/ /ua/ /uo/ /uai/ /uei/ /uan/ /uen/ /uang/ /ueng/ // /e/ /an/ /n/

English /:/ /i/ /e/ a:/ // /]/ ]:/ /u/ /u:/ /c/ /c:/ /ei/ / i/ /ic/ uc/ /ec/

//

Speakers of the Chinese national language may insert a schwa (the schwa is the vowel sound in many lightly pronounced unaccented syllables in words of more than one syllable) in consonant clusters such as /belek/ for the word black or omit a consonant, pronouncing the word strawberry as /troberi/. Another difficulty for Chinese learners of English is to discriminate between the //, /e/, / /and //. Chinese learners may be prone to pronounce back as bike, hat as hurt, and head as hide because these sounds are not clearly discriminated in their mother tongue. Chinese speakers of English may sometimes sound telegraphic, i.e., lacking of variations in pitches. It may also be difficult for Chinese learners to adapt to English intonation patterns, e.g. those which signal the difference between a question and a statement (Cheng, 2001). Furthermore, Chinese speakers tend to omit final sounds in English, for example, wi/wife. Or sometimes they add an extra sound when producing English: gooda/good. Chinese speakers sometimes shorten or lengthen the vowels in English: seat/sit. Other difficulties for Chinese learners acquiring the phonological system arise from Chinese being monosyllabic and tonal. In Putonghua, there are four tones (plus a neutral tone): the first tone has a high level, the second tone is rising, the third tone is falling-rising and the fourth tone is falling. Each Chinese dialect has its own tonal system, each with a different number of tones. A good example of the difficulties of the tonal system is the sentence Mama ma ma ma? (Does mother chide the horse?). Here the first word mama (mother) has a high level tone for the first vowel and a neutral tone on the second vowel. The second word ma (chide) has a falling tone. The third word ma (horse) is falling-rising tone and the last ma (question mood marker) is in rising tone. Whereas English words are usually constituted of two or more syllables, Chinese characters are monosyllabic. Each syllable consists of segmental and suprasegmental features, including an initial consonant and a final sound. These major differences between the phonetic systems of the Chinese national language and English require further discussion where a more detailed contrastive analysis can be made.

http://www.uwo.ca/sogs/WJGR/2005/WJGR2005_v12_p113_Zhang.htm

03/05/2012

Page 3 of 4

Grammatical contrast Because of the vast distance between the written and spoken forms of English, learners of English may encounter communication difficulties in ways that is unthinkable for native speakers. For example, the characters referring to male and female are different in Chinese but they are pronounced the same (ta). Therefore, many Chinese learners find it hard to differentiate between she and he in oral English. With regard to numbers, Chinese sometimes uses the character men to denote a plural form, wo is I (or me), women is we (or us); ta is he (or she), and tamen is they (or them). There are more exceptions than rules (e.g., one ship is a ship but two ships are still expressed as two ship in Chinese). There is also a lack of agreement between a subject and its verb. For example, the equivalents for eat in I eat and he eats are the same. No inflectional forms are needed. Articles are also quite different between English and Chinese. The Chinese language does not need a definite article to modify a word or phrase. The English tense and voice system are also perplexing for Chinese learners. The Chinese language uses different phrases to refer to different times. It is correct to say I go home tomorrow, yesterday, and even already. Many Chinese students also find it hard to differentiate between the passive and active voices, and use different verb forms accordingly. Lexical differences In terms of lexical differences, the Chinese language does not put wh-words (e.g., who, what, when, where, how) at the beginning of a sentence. Any sentence ending with a ma and a rising tone is interrogative, irrespective of (special or general) interrogative forms. Sentences like you are doing what and you are ok are perfect sentences according to Chinese lexical order. Chinese learners of English are always puzzled as to why a verb sometimes becomes a modal, denoting a special emotion. They cannot understand why the sentence Can you come here? is any different from the sentence Could you come here?. It is very confusing for Chinese learners that they can say it is cold, but not the sky is cold. After all, the weather is mother natures business, it is not personal. Some structures must be practiced frequently before learners can understand why it is correct to say there are four seasons in a year, rather than the year has four seasons. It takes time for the learners to get accustomed to the usages of certain lexical structures. Throughout my teaching and learning practice, I have noticed some typical mistakes by Chinese learners. Here are some examples of other sentences that I have discovered through my teaching experience that are very confusing to English speakers, but are perfectly understandable to someone whose first language is Chinese: My English base is very poor and composition is always my weakness. I must make use of a strong measure to raise my English level all round. Reading made me learn a lot of new words. The numbers of words I have mastered have enlarged- I have studied more than 5000 English vocabularies. Except for studying the textbook, I also insist on reading China Daily. This year my listening skills have made much progress. Although I like the dictionary, but its price is expensive. Reference books are reference books. They cannot instead of our studying. Somebody just know to copy answers. Because they are lazy. I suggest the teacher had better help us win much more chances to have the oral communication.

To summarize, morphological/grammatical (e.g., modal verbs, tenses, articles, word orders, syntax, construction, and prepositions) of both languages are highly varied. These differences are manifested in the learners L2 even as they progress. No one can claim to be untouched or uninfluenced by the lingering influences of their L1. In this section, phonological, grammatical, and lexical differences are presented in contrastive analysis. A complete CAH analysis also entails comparing similarities between both languages. The most obvious similarity between Chinese and English is the centrality of verbs in a sentence for both languages. Other similarities such as the categorization of three persons and the lack of gender-related verb conjugations are also prominent. What follows is an excerpt from my work on the oral communication skills of Chinese learners in Canada. It mainly relates to the interviewees awareness of their learning difficulties that stem from structural differences between their two languages, English and Mandarin Chinese. Two students perceptions At the end of 2003 and beginning of 2004, I conducted research into oral communicative competence in 8 Chinese students enrolled in a Canadian institution of higher education. Amongst the interviewees, most felt that their learning difficulties partly resulted from the structural differences between Chinese and English. Two students stories are presented in the following to exemplify this view and my earlier discussion of CHA. Yong reports having learned English for 19 years; since she was 11 years old. Before coming to Canada for her Masters degree, she was an EFL course instructor in a Chinese university for 5 years. She speaks and writes English quite fluently and is considered to be a competent learner by her professors and peers. However, she thinks that the strategies that she employed when she began to learn English were heavily influenced by the strategies she employed acquiring her first language. Her strategy was to concentrate on memorization. According to her, the pictographic nature of the Chinese language requires its learners to exert much effort memorizing strokes and combinations of strokes before they can fully comprehend the ideological connotations. As noted by Cortazzi & Jin (1996), Chinese people believe that to learn a language mainly involves acquiring a large vocabulary and the general rules of sentence structures. These are regarded as the foundation for further improvement of language competence, but they are not attainable unless one is willing to make the effort to memorize them. The traditional way of learning Chinese is by emphasizing memory work, imitation, and repetition. Subsequently, these strategies and assumptions are carried on when learners encounter a foreign language at a later stage. Yong began learning English when she was around 10. At that time she had no idea that what was written could be different from what was spoken. Yong recalls: I had no idea of phonemic awareness, and the English phonological system did not make any sense to me. Therefore I copied the spelling of the English words many times on a piece of paper and, at the same time, read with a tape many times to memorize the pronunciation. That was exactly what she was required to do at the beginning of her Chinese literary learning, to copy the Chinese characters and memorize the pronunciations. The Chinese emphasis on analyzing structures explains the prediction which many Chinese learners of English have for the grammar translation approach to EFL teaching and learning. This approach helps Chinese learners of English make grammatically correct sentences, but does not enhance their language competence, especially their communicative competence. Rather, this practice leads Chinese learners of English to be tongue tied when trying to figure out which words to use, and what the correct sequence of wording should be. This over reliance on knowledge of their L1 to produce English discourse highlights the importance of structural contrastive analysis. As Yong puts it: Even now I have problems with he and she in my oral English. In addition, tense and the plural forms in English are still bothering me frequently. Here again, CAH can be very useful in understanding the reason behind this. Another student, Wei, has been learning English for 10 years. He is a typical Chinese EFL learner who learned English for 3 years in Junior middle school, 3 years in Senior middle school, and 4 years at university. An English major, Wei says he usually has no difficulty communicating with the professors and classmates. However, he reports that successful communication eludes him at times because, even if he tries to speak slowly to give himself more time to finish the code-switching process, mistakes are still apparent everywhere. What compounds this process is that he can recognize his mistakes immediately after finishing his comments, and really feels bad about that. He recalls his experiences in similar situations and the reason behind that. As he puts it: It is hard to make every sentence correct because I seem always to choose the wrong words. For example, I always use she to refer to a male, and he to refer to a lady, because in Chinese you never bother to differentiate that when speaking. Also, it is hard to use the correct tenses, especially present and past tenses. I sometimes begin telling a story in the past tense, but as the story progresses, present tenses seem to be more ready to slip through. Another easy mistake is the active voice and passive voice because many times they are hard to decide when you have to reply spontaneously. Countable and uncountable nouns are also hard to differentiate because they not only have different inflectional forms, but also call for different modifiers. For example, you can only say much water, but not many water. Another thing is the third person singular, it is easy to omit the s in daily speaking. All these complicated forms never appear in Chinese, so in a sense, Chinese appears to be a much simpler language system compared with English As a competent speaker of English he said that in many cases, he knows there are different structures in English and Chinese and that these differences cause a lot of trouble in daily communication. Sometimes, he is able to identify the mistakes immediately after making them, and sometimes before making the utterances, so that he can speak correctly. Wei said he is more confident in his ability to write English because writing affords him the time to choose his wording, craft his writing, and totally forget about his L1. Besides, he had more practice writing English while he was in China. Discussions From theory to practice, CAH proves to be still alive and well, and useful for language learners, educators, and researchers. Although it may appear crude and appear to mainly focus on the product rather than the process, it is facilitative to the understanding of difficulties confronted by many language learners. Stockwell and Bowens (1965) argument that there exists a hierarchy of difficulty of learning problems based on types of differences between languages is still appealing to many language learners and researchers, especially those whose first language are non-English. Their assertion that the greater the difference between languages, the more persistent the predicted

http://www.uwo.ca/sogs/WJGR/2005/WJGR2005_v12_p113_Zhang.htm

03/05/2012

Page 4 of 4

errors will be, is very convincing, at least from the perspective of EFL learners. As Fisiak (1990) points out, the dynamic development of contrastive research has been more, if not predominantly, a European rather than an American phenomenon. Today, there is very little research in this area. As noted earlier interesting research is being conducted by Davis (2002) in Hong Kong. This suggests that teachers who are aware of a few of the grammatical differences between English and Chinese can help students trouble-shoot grammar hot spots and minimize errors through proof-reading. Grammatical accuracy in English requires much more tweaking than it does in Chinese. As a researcher whose first language is considered to be distant to English, I think a contrastive analysis approach complements existing language learning and teaching theories. Interlanguage can be regarded as an on-going process of L2 development where L1 structures persist on appearing due to language differences. This process is a continuum that will never finish, especially for adult second language learners. Researchers focusing on interference and code switching should also find this study enlightening because one possible reason for interference is structural difference. CAH provides a new perspective for understanding this process. Curriculum developers should also find this analysis useful and incorporate these findings into their development of pedagogical materials for target groups. To conclude, contrastive analysis makes a lot of sense by providing a more insightful perspective into the understanding of second language learning/teaching, especially from the perspective of researchers and learners whose L1 is Chinese and L2 is English. Contrastive analysis can and should be incorporated into the communicative language teaching classes, especially in the English as foreign language (EFL) classrooms. It is my argument that CAH can be facilitative for ESL/EFL researchers and practitioners to further understand the process of language teaching and learning.

References Berthold, M., Mangubhai, F., & Batorowicz, K. (1987). Bilingualism and multiculturalism: Study book. Distance Education Centre, University of Southern Queensland: Toowoomba, QLD. Cheng, L.L. (2001). Transcription of English influenced by selected Asian languages. Communication Disorder Quarterly, 23 (1), 40-45. Cook, V. (1991). Second language learning and language teaching. Melbourne, Australia: Edward Arnold/Hodder Headline Group Cortazzi, M. & Jin, L. (1996). Cultures of learning: Language classrooms in China. In H. Coleman (Ed.), Society and the language classroom, pp.169-206. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Crystal, D. (1987). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge University Press. Davis, A. M. (2002). Increasing our awareness of Chinese grammar: Contrastive analysis can help English learners. Retrieved February 16, 2004 from http://www.eslminiconf.net/may/story1.html. Frch, C. & Kasper, G. (Eds.) (1987). Introspection in second language research. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters. Fisiak, J. (1990). On the present status of some metatheoretical and theoretical issues in contrastive linguistics. In J. Fisiak (Ed.) Further insights into contrastive analysis, pp. 3-22. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins publishing company. Fries, C. C. (1945). Teaching and learning English as a foreign language. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. Gass, S. M., & Selinker, L. (1994). Second language acquisition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Geethakumary, V. (2002). A contrastive analysis of Hindi and Malayalam [Electronic version]. Language in India. 2 (6). Grandgent, C. H. (1892). German and English sounds. Boston, USA: Ginn. Lado, R. (1957). Linguistics across cultures. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. Milroy, L. (1987). Observing and analyzing natural language: A critical account of the sociolinguistic method. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers. Nickel, G. (1971). Papers in contrastive linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OMalley and Chamot (1990). Learning strategies in second language acquisition. Cambridge UP. Passy, J. (1912). Petite phoetique comparee des principles langues European. Teubner, Leipzig. Schacter, J. (1974). An Error in Error Analysis. LL 24(2), 205-214. Schackne, S. (2002). Language teaching research: In the literature, but not always in the classroom, Journal of Language and Linguistics 1/2. Stockwell, R. R., & Bowen, J. D. (1965). The sounds of English and Spanish. Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press. Wardhaugh, R. (1970). The Contrastive analysis hypothesis. TESOL Quarterly, 4 (2), 123-130. Whorf, B. L. (1941). Language, mind, and reality. In John B. Carroll (ed.) Language, Thought, and Reality, (246-270). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Zhang, L. (2002). Overcoming accents: A contrastive analysis of the phonological differences between English and Chinese. Paper presented at the First Annual UWO Conference on Applied Linguistics on May 7-8 2002 at The University of Western Ontario, Canada Zhou, M. (2002). The spread of Putonghua and language attitude changes in Shanghai and Guangzhou, China. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 11 (2), 231-253.

http://www.uwo.ca/sogs/WJGR/2005/WJGR2005_v12_p113_Zhang.htm

03/05/2012

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Lexicology Course Description BujaDocument2 pagesLexicology Course Description BujaIoana Alexandra100% (1)

- Cardinal Vowel TheoryDocument14 pagesCardinal Vowel TheoryAhmed Shojib50% (2)

- How Language Changes: Group Name: Anggi Noviyanti: Ardiansyah: Dwi Prihartono: Indah Sari Manurung: Rikha MirantikaDocument15 pagesHow Language Changes: Group Name: Anggi Noviyanti: Ardiansyah: Dwi Prihartono: Indah Sari Manurung: Rikha MirantikaAnggi NoviyantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparing the Formal and Functional Approaches to Discourse AnalysisDocument16 pagesComparing the Formal and Functional Approaches to Discourse AnalysisVan AnhPas encore d'évaluation

- Phonology in Language Learning and Teach PDFDocument18 pagesPhonology in Language Learning and Teach PDFakhilesh sahooPas encore d'évaluation

- Learner Language in Korean Classrooms: Implications For TeachingDocument34 pagesLearner Language in Korean Classrooms: Implications For Teachingmartinscribd750% (2)

- Manual of American English Pronunciation for Adult Foreign StudentsD'EverandManual of American English Pronunciation for Adult Foreign StudentsPas encore d'évaluation

- Teacher TalkDocument6 pagesTeacher TalkGloria GinevraPas encore d'évaluation

- Computer-Assisted Pronunciation Teaching (CAPT) To Overcome Pronunciation Difficulties Among EFL BeginnersDocument9 pagesComputer-Assisted Pronunciation Teaching (CAPT) To Overcome Pronunciation Difficulties Among EFL BeginnersInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyPas encore d'évaluation

- Contrastive Analysis HypothesisDocument16 pagesContrastive Analysis HypothesisMohamed BamassaoudPas encore d'évaluation

- Spanish Grammar TipsDocument7 pagesSpanish Grammar TipsChittaranjan HatyPas encore d'évaluation

- Language Family Language Family: Siti MukminatunDocument46 pagesLanguage Family Language Family: Siti MukminatunAnallyPas encore d'évaluation

- Velarization: A Secondary ArticulationDocument6 pagesVelarization: A Secondary ArticulationMohammed MasoudPas encore d'évaluation

- Sign Language Phonology - ASLDocument18 pagesSign Language Phonology - ASLOpa YatPas encore d'évaluation

- An Analysis of Grammatical Errors in Academic Essay Written by The Fifth Semester Students of English Education Study Program of UIN Raden Fatah PalembangDocument181 pagesAn Analysis of Grammatical Errors in Academic Essay Written by The Fifth Semester Students of English Education Study Program of UIN Raden Fatah PalembangRegina RumihinPas encore d'évaluation

- The Audio-Lingual Method of Teaching EnglishDocument11 pagesThe Audio-Lingual Method of Teaching EnglishWill Lake100% (1)

- Language Teaching TheoriesDocument47 pagesLanguage Teaching TheoriesKevinOyCaamal100% (1)

- Interlanguage Error Analysis: an Appropriate and Effective Pedagogy for Efl Learners in the Arab WorldD'EverandInterlanguage Error Analysis: an Appropriate and Effective Pedagogy for Efl Learners in the Arab WorldPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3 - BorrowingDocument5 pagesChapter 3 - BorrowingElisaZhangPas encore d'évaluation

- GESE Guide for Teachers: Initial StageDocument29 pagesGESE Guide for Teachers: Initial StageclaudiaPas encore d'évaluation

- World-Readiness Standards (General) + Language-specific document (GERMAN)D'EverandWorld-Readiness Standards (General) + Language-specific document (GERMAN)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Classroom Learning Second Language Acquisition 29dnoorDocument9 pagesClassroom Learning Second Language Acquisition 29dnoorA RPas encore d'évaluation

- Second Language Learning - Lightbown & Spada, Chapter 2Document22 pagesSecond Language Learning - Lightbown & Spada, Chapter 2LenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching English For Specific Purposes (ESP)Document4 pagesTeaching English For Specific Purposes (ESP)Oana GăianuPas encore d'évaluation

- Chinese-English Contrastive Grammar: An IntroductionDocument36 pagesChinese-English Contrastive Grammar: An IntroductionSir Francis DelosantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Inflection 1. Inflection 1. Inflection 1. InflectionDocument23 pagesInflection 1. Inflection 1. Inflection 1. InflectionOpa YatPas encore d'évaluation

- Grammar Translation MethodDocument4 pagesGrammar Translation MethodnilsusudePas encore d'évaluation

- Zimmerman C and Schmitt N (2005) Lexical Questions To Guide The Teaching and Learning of Words Catesol Journal 17 1 1 7 PDFDocument7 pagesZimmerman C and Schmitt N (2005) Lexical Questions To Guide The Teaching and Learning of Words Catesol Journal 17 1 1 7 PDFcommwengPas encore d'évaluation

- 13 Ling 21 - Lecture 3 - NeurolinguisticsDocument29 pages13 Ling 21 - Lecture 3 - Neurolinguisticsneneng suryaniPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Introduction To Discourse AnalysisDocument10 pages2 Introduction To Discourse AnalysisrayronaPas encore d'évaluation

- Phoneme isolation constraints in Dutch kindergartnersDocument17 pagesPhoneme isolation constraints in Dutch kindergartnersboufriss0% (1)

- Averil Coxhead - Pat Byrd - 2007Document19 pagesAveril Coxhead - Pat Byrd - 2007mjoferPas encore d'évaluation

- Author Insights Paul Davis Hania KryszewskaDocument2 pagesAuthor Insights Paul Davis Hania KryszewskaEmily JamesPas encore d'évaluation

- Second Language Learning - Lightbown & Spada, Chapter 2Document22 pagesSecond Language Learning - Lightbown & Spada, Chapter 2LenaPas encore d'évaluation

- History of LinguisticsDocument33 pagesHistory of LinguisticsKamakshi RajagopalPas encore d'évaluation

- CO Approaches To TEFL 2016Document5 pagesCO Approaches To TEFL 2016Muhamad KhoerulPas encore d'évaluation

- PSYC2208: Language and Cognition reading listDocument10 pagesPSYC2208: Language and Cognition reading listJames Gildardo CuasmayànPas encore d'évaluation

- Applied LinguisticsDocument23 pagesApplied LinguisticsYaf ChamantaPas encore d'évaluation

- (Understanding Language) Kate Burridge - Alexander Bergs - Understanding Language Change-Routledge (2017)Document314 pages(Understanding Language) Kate Burridge - Alexander Bergs - Understanding Language Change-Routledge (2017)IchtusPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 2Document70 pagesChapter 2anil2002twPas encore d'évaluation

- Nanosyntax Meets The Khoesan Languages Hadza Pronouns and The Inclusive Exclusive DistinctionDocument2 pagesNanosyntax Meets The Khoesan Languages Hadza Pronouns and The Inclusive Exclusive DistinctionAdina Camelia BleotuPas encore d'évaluation

- Direct Method 5 TechniquesDocument9 pagesDirect Method 5 TechniquesAlexandru Lupu100% (1)

- The Problem of Polysemy in The English LanguageDocument41 pagesThe Problem of Polysemy in The English LanguageOgnyan Obretenov100% (2)

- Seminar Paper - RevisionsDocument22 pagesSeminar Paper - RevisionsMikhael O. SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Common Errors By Spanish Speakers Learning EnglishDocument4 pagesCommon Errors By Spanish Speakers Learning EnglishNati Rodriguez GilPas encore d'évaluation

- Code Switching in Conversation Between English Studies StudentsDocument39 pagesCode Switching in Conversation Between English Studies StudentsTarik MessaafPas encore d'évaluation

- Dealing With DifficultiesDocument33 pagesDealing With DifficultiesMarija Krtalić ĆavarPas encore d'évaluation

- Error Analysis in A Learner Corpus.Document16 pagesError Analysis in A Learner Corpus.Tariq AtassiPas encore d'évaluation

- Sociolinguistics Studies of Language VariationDocument22 pagesSociolinguistics Studies of Language VariationDekaPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Language AcquisitionDocument7 pagesWhat Is Language AcquisitionMuhammad AbidPas encore d'évaluation

- Types of Linguistic ChangeDocument6 pagesTypes of Linguistic ChangeRandy GasalaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Using Local Languages in English Language ClassroomsDocument5 pagesUsing Local Languages in English Language ClassroomsMica Kimberly UrdasPas encore d'évaluation

- Tugas 1 ESP PDFDocument1 pageTugas 1 ESP PDFFachmy SaidPas encore d'évaluation

- Lexical ApproachDocument10 pagesLexical ApproachRyan HamiltonPas encore d'évaluation

- Evolution of English GrammarDocument5 pagesEvolution of English GrammaryunangraeniPas encore d'évaluation

- Linguistics As ScienceDocument12 pagesLinguistics As ScienceSinPas encore d'évaluation

- The Structure of SentencesDocument16 pagesThe Structure of SentencesRahmat CandraPas encore d'évaluation

- Improving Students Vocabulary Through Blindfold Games: Tauricha AstiyandhaDocument11 pagesImproving Students Vocabulary Through Blindfold Games: Tauricha AstiyandhaKris GoodluckPas encore d'évaluation

- Contrastive Grammar Josef SchmiedDocument7 pagesContrastive Grammar Josef SchmiedHendrik Lin Han Xiang100% (1)

- How To Make TransparentDocument2 pagesHow To Make TransparentHendrik Lin Han XiangPas encore d'évaluation

- Application of Palm-Based Interesterified FatsDocument7 pagesApplication of Palm-Based Interesterified FatsHendrik Lin Han XiangPas encore d'évaluation

- Embedded Ru@Zro Catalysts For H Production by Ammonia DecompositionDocument11 pagesEmbedded Ru@Zro Catalysts For H Production by Ammonia DecompositionHendrik Lin Han XiangPas encore d'évaluation

- UT Dallas Syllabus For crwt3351.001.07s Taught by Susan Briante (scb062000)Document7 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For crwt3351.001.07s Taught by Susan Briante (scb062000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupPas encore d'évaluation

- Book Review The Gothic, Postcolonialism and Otherness - Ghosts From Elsewhere PDFDocument4 pagesBook Review The Gothic, Postcolonialism and Otherness - Ghosts From Elsewhere PDFfaphonePas encore d'évaluation

- Gellrich, Socratic MagicDocument34 pagesGellrich, Socratic MagicmartinforcinitiPas encore d'évaluation

- LaroseThe Abbasid Construction of The JahiliyyaDocument18 pagesLaroseThe Abbasid Construction of The JahiliyyaNefzawi99Pas encore d'évaluation

- De Arte Graphica. The Art of PaintingDocument438 pagesDe Arte Graphica. The Art of PaintingMarco GionfaloPas encore d'évaluation

- Intro To Orwell 1984Document44 pagesIntro To Orwell 1984Elizabeth ZhouPas encore d'évaluation

- Baranovitch. Nimrod 2003 China's New VoicesDocument349 pagesBaranovitch. Nimrod 2003 China's New Voices신현준Pas encore d'évaluation

- Faerie Queen As An AllegoryDocument3 pagesFaerie Queen As An AllegoryAngel Arshi89% (18)

- High Waving HeatherDocument2 pagesHigh Waving HeatherManuela NevesPas encore d'évaluation

- A Poison TreeDocument3 pagesA Poison TreeJess DjbPas encore d'évaluation

- HRM Assignment Brief: SEP2018-19: General Guidelines: - Individual Assignment With 50 % WeightingDocument8 pagesHRM Assignment Brief: SEP2018-19: General Guidelines: - Individual Assignment With 50 % WeightingNiomi GolraiPas encore d'évaluation

- Tadros Yacoub Malaty - A Patristic Commentary On 1 TimothyDocument132 pagesTadros Yacoub Malaty - A Patristic Commentary On 1 Timothydreamzilver100% (1)

- The Big Issue in South AfricaDocument44 pagesThe Big Issue in South AfricaSarah HartleyPas encore d'évaluation

- I Puc Sanskrit PDFDocument187 pagesI Puc Sanskrit PDFMassimo FaraoniPas encore d'évaluation

- CNF ReviewerDocument2 pagesCNF Reviewergina larozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Arabian LiteratureDocument9 pagesArabian LiteratureNino Joycelee TuboPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To The Guan Yin Citta Dharma DoorDocument113 pagesIntroduction To The Guan Yin Citta Dharma Doormurthy2009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Renaissance CharacteristicsDocument14 pagesRenaissance CharacteristicsYusraaa Ali100% (1)

- Introductory Study Towns and Cities of T PDFDocument48 pagesIntroductory Study Towns and Cities of T PDFmalovreloPas encore d'évaluation

- Antigone-Analysis of Major CharactersDocument2 pagesAntigone-Analysis of Major CharactersGharf SzPas encore d'évaluation

- The Poetry of Robert FrostDocument41 pagesThe Poetry of Robert FrostRishi JainPas encore d'évaluation

- Sijo PoetryDocument16 pagesSijo PoetryAlmina15Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Post Card From HellDocument11 pagesA Post Card From HellJayaraj TPas encore d'évaluation

- 40 Prophetic Narrations of TribulationDocument6 pages40 Prophetic Narrations of TribulationscribdpersonalPas encore d'évaluation

- Rancangan Semester English NewDocument4 pagesRancangan Semester English NewNormazwan Aini MahmoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Rebecca West's 'Constantine The Poet' by Michael D. Nicklanovich (1999)Document6 pagesRebecca West's 'Constantine The Poet' by Michael D. Nicklanovich (1999)Anonymous yu09qxYCMPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL Q1Document3 pagesDLL Q1K.C. Mercado Santos0% (1)

- Socratic Circles Handout: The Chrysalids Novel StudyDocument1 pageSocratic Circles Handout: The Chrysalids Novel Studyascd_msvu67% (3)

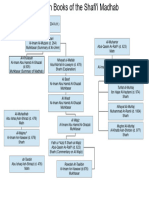

- Main Books of Shafii Madhhab ChartDocument1 pageMain Books of Shafii Madhhab ChartM. A.Pas encore d'évaluation