Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Spirit Play Analysis and Evaluation D. Alethea Hession Curriculum Theory and Development Spring, 2012

Transféré par

Alethea ShiplettTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Spirit Play Analysis and Evaluation D. Alethea Hession Curriculum Theory and Development Spring, 2012

Transféré par

Alethea ShiplettDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Running Head: SPIRIT PLAY

Spirit Play Analysis and Evaluation D. Alethea Hession Curriculum Theory and Development Spring, 2012

SPIRIT PLAY

Table of Contents Introduction Evaluation Criteria The Learner Teacher Training Environment/Physical Space Methodology Findings Foundations in Montessori Role of the Teacher Role of the Environment Recommendations Conclusion References 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 5 7 8 9 11 12

SPIRIT PLAY

Spirit Play Analysis and Evaluation Introduction Spirit Play is a Montessori-based approach for religious education designed specifically for the Unitarian Universalist (UU) faith community, yet applicable for any liberal religious faith community. It follows the design of the religious education model developed by Sofia Cavalletti, a protg of Maria Montessori, called Catechesis of the Good Shepherd, and its Protestant counterpart, Jerome Berrymans Godly Play model (Barryman, 1995). Through story, ritual, and creativity, children are given the tools and language to inquire into the meaning of their lives within the context of the principles, history and spiritual sources of Unitarian Universalism (Penfold, 2008). The Spirit Play curriculum is designed for mixed age environments, with children ranging in ages from 4 through 10, or may be narrowed for more traditional church school age groupings of 2-3 years. The children are led in by the door keeper (assistant) to sit in a circle. The teacher, or story teller, leads the children in an opening ritual to center themselves through a breathing exercise, chant or similar opening and centering activity to set the tone. The story teller then presents the story box or lesson for the day. After the presentation of the story through materials and objects, the lesson ends with a wondering. The story teller offers several statements beginning with I wonder. The children are free to contribute their thoughts. There are no wrong answers. After the wondering, the materials are returned to their basket or tray and the story or lesson is returned to the shelf. The children are then dismissed to freely explore the environment for the remainder of the class, selecting to work with a

2

SPIRIT PLAY

previously demonstrated story box, activities in one of the centers, or in creating some artistic piece of their choosing. Some programs include a shared time for eating a snack, called feast, with rituals for opening and closing the feasting time. At the end of class, the children are signaled to clean up. Before they leave, the door keeper says goodbye to each child in a special, ritualized way, using the phrase, Go now in peace. In Spirit Play, the core content is organized around three foundational lessons: the seven Unitarian Universalist principles, termed promises, the Sources lessons, and the Flaming Chalice lessons (Penfold, 2008). At the heart of these three components is a curriculum that builds community and compassion, based on investigation of truth and democratic principles, encouraging questioning, and dialogue around the greater existential questions by providing vocabulary to articulate ones own theology and meaning-making. Evaluation Criteria The Spirit Play curriculum will be evaluated under three broad categories: 1) the learner, 2) teacher training, and 3) environment and physical space. The Learner The effectiveness of any curriculum must answer the question: How well does the content meet the learner? Is the curriculum able to engage the learner in translating the content into meaningful knowledge, wisdom and application? Are the curriculum materials and content developmentally appropriate to the characteristics, needs, abilities, identities and learning styles of the target age range of learners? Does the curriculum allow for a wide array of developmentally appropriate approaches, instructional strategies and tools to connect learners positively to the content? (NAEYC, 2011)? Does the curriculum take into consideration

3

SPIRIT PLAY

each child as an individual with a story, interests, experiences, questions (File, Mueller & Wisneski, 2011). Is the content transmitted in diverse ways for individual, independent works, as a social activity, between learners, and between the learner and more capable others (Vygotsky, 1978)? Does each child see her/himself represented in the content and materials? How does the curriculum treat with respect the importance and complex characteristics of childrens families and communities? Does it connect learners to their families and the larger community (NAEYC, 2011)? Teacher Training Successful implementation of curriculum lies in the hands, talents and activities of the teachers. Key to buy-in on the part of the teachers lies in how well they feel supported, nurtured and engaged as creative participants in the curriculum (Penfold, 2008). What special training or support is necessary for the successful implementation of the curriculum? What are the costs, length and level of teacher training required? What type of on-going teacher support is necessary or useful? Environment/Physical Space As with any program, limitations in terms of financial resources, materials and physical space are important considerations, especially in small programs such as Sunday Schools. Will the environment and physical space support the implementation of the curriculum? Are there adequate shelves, floor space, work space, storage to accommodate curriculum components? Is the curriculum appropriate for the setting, in terms of ease of use and materials required to implement the curriculum? Are the costs financially manageable? What are the continuing costs, if any (Penfold, 2008)?

4

SPIRIT PLAY

Methodology The evaluation of the effectiveness of the Spirit Play curriculum is supported by research, articles and texts covering theoretical expertise, information on human development and brain-based learning, and nationally accepted standards for programs for young children. Nearly 30 years of Montessori practice, training and implementation in the Godly Play model, the Spirit Play model, and development of a model for implementation for children in the Bahai Faith community also informs findings and recommendations of the author in subsequent sections of this paper. Findings The evaluation criteria for Spirit Play focus on the three components of the classroom the learner, the teacher and the physical environment. The theoretical framework for Spirit Play challenges the traditional definition of curriculum as content. Instead, Spirit Play offers a framework in which all three components of the classroom act together as tools to create meaning for the child. The activity connects the childs own feelings or ideas to the concept being presented(Penfold, 2008, p. 82). Foundations in Montessori Montessori in general, and Spirit Play in particular, provides a wide diversity of materials and opportunities for learning in a mixed-age, mixed-ability environment. The curriculum contains extension lessons for older children (10-12). The emphasis is on the child and his or her contact with the materials and choices in the environment. The teachers role is to observe the children and guide them to materials that will best help them learn to be independent and peaceful members of the community and to express their deepest selves

5

SPIRIT PLAY

(Penfold, 2008, p. 22-3). Spirit Play, as in other Montessori-based environments, easily serves children of all intelligences and styles of learning musical, bodily-kinesthetic, spatial, interpersonal, intrapersonal, intuitive and linguistic and logical-mathematical (Stephenson, 2000). Instead of taking a teacher-centered, didactic approach to communicating this content, Penfold states that (t)hrough the Montessori elements, Spirit Play creates a structure that trusts the child to be drawn to what he or she needs at whatever level of development (p. 15). This childcentered approach honors the child as a competent learner, spiritual questioner and meaningmaker on a spiritual journey of his or her own, and in community with others. Whereas adult work is focused on achieving a goal or making a change, the work of the child is selfconstruction (Haines, 2000). Spirit Play provides the language for this self-construction and self-inquiry to take place. The environment, materials and methods accommodate children with diverse learning abilities with slight adjustment. For example, children with ADD or ADHD have been observed demonstrating focused activity when free to choose work which is of interest to them. Children are often permitted to bring an attachment item such as a doll or stuffed animal to help them feel safe or comfortable. Interpreters may be provided to help children with language differences to participate more fully (Penfold, 2008). The layout of the environment may be adjusted for wheelchairs. The wondering component at the end of the presentation provides the contact between the story and the child. It makes the content authentic and meaningful to the childs life and experience:

6

SPIRIT PLAY

I wonder what part of this story you liked best. I wonder what the most important part of this story was. I wonder where you see yourself in this story. I wonder how you might feel if this happened to you. Penfold describes the wondering statements as tools to help children to wonder about what it is like to be in our community, what happens when we make or break promises to one another, where all these ideas came from in the first place and where they fit in all of this (Penfold, 2008, p. 28). How the children answer the questions comes out of their own internal, processing of the story at their own level of development (Penfold, 2008, p. 77). The Role of the Teacher The unique role of a Montessori teacher requires skills in observation, detachment, reflective listening, and ability to present lessons in a clear and logical sequence (Gutex, 2004). A one-day training workshop, including a handbook and a CD of dozens of stories, currently costs between $150-$200. The story box lessons provided on the CD also list materials needed and the script for presenting the story or lesson. Adults unfamiliar with the Montessori method must redefine their role from that of teacher of content to story teller and witness to the childs spiritual emergence (Penfold, 2008, p. 81). Some training in the Montessori approach is provided in the Spirit Play workshop. The teacher assesses how well the children understand and incorporate the principles into daily practice by observing the childrens dialogue to see if the principles of cooperation and community are manifest among the children. When conflicts arise, the teacher can ask which promise may apply to the situation. The teacher must also create a non-judgmental

7

SPIRIT PLAY

atmosphere particularly when conducting the wondering or when commenting on the art responses of the children. Penfold advises the teacher to ask Tell me about your work, rather than commenting on its quality or attributes (2008, p. 82). The Role of the Environment Much of the power latent in the curriculum lies within the structure of the environment. Placing materials on shelves, limiting the quantity of art supplies to encourage sharing and collaboration, creating a sense of sacred space with lovely pictures and posters, orderly and attractive materials set the tone for reflection and contemplative work. The environment should contain adequate floor or table space for the children to lay out the story box materials or work with the art materials. Since space is often at a premium in churches, Spirit Play can be transported and set up in milk crates or other containers. Initial start-up costs can be expensive unless some creativity is exercised. Art supplies are typically available from church storage rooms. Small objects, clay, buttons and fabric can be found in craft and fabric stores. Baskets and trays can be obtained cheaply at second-hand stores and yard sales. Shelves, tables and chairs can be obtained by donations or on free exchange websites, such as freecycle (www.freecycle.net), or re-purposed from Sunday School rooms for the Spirit Play environment. Spirit Play, and the Godly Play model upon which it is based, considers the environment to be a community of children (Barryman, 1995). Objects such as brooms, trays, materials, tables and chairs should be child-sized and at child level. Likewise, at the end of the session, the children are responsible to clean up from their activities, reinforcing their ownership and responsibility for the environment and their activity in it. In this way, independence,

8

SPIRIT PLAY

responsibility and community are fostered. When adults visit the environment, they are expected to sit outside of the circle on a chair by the door. During free exploration, visiting adults are advised not to interact unduly with the children. Recommendations The Spirit Play curriculum can seem strange and confusing to children visiting for the first time in the middle of the church year. The orientation and introductory lessons were offered in September. New or visiting children are therefore somewhat lost, as are new or visiting parents. In order to make visitors more comfortable when they first attend the Wonder Hour program, the following recommendations/modifications are offered: 1) Provide a lesson presentation designed to introduce the child/parents to the layout of the environment the 7 stations and activities offered. This consists of label cards that match the signs around the room designating the name of the center with a simple icon that symbolizes the theme. For example, the center Our Home has a picture of the earth on the sign. The corresponding label card would also contain a picture of the earth. The label cards would also correspond to the same color as the signs, making the seven colors of the rainbow. Through these materials, the child would be guided through the environment to visit each center to see the activities offered there. 2) At the close of the circle, the teacher reviews the protocols for free choice time walking quietly, speaking softly, using a work mat, putting work away, etc., to help the visitors know what to expect during free choice time and departure. 3) The teacher invites a child well acquainted with the environment to serve as a buddy to the visitor(s).

9

SPIRIT PLAY

The materials offered on the shelves are geared toward younger children (4-10 years). Recommendations for older children include: 1) Providing extension activities and cards that supplement the story box offers more challenging content to engage the older children (10-12 years). 2) A sewing bin and embroidery bin for hand-sewing puppets, doll clothes, plastic stitching frames and yarn, scissors and knitting or crocheting needles. 3) Extension lesson cards with written biographies, histories and other key features, on laminated cards. Cards featuring sacred places around the world with matching description cards, or expansion on the seven principles and various wordings and writings which elaborate on the principles. Although the environment is designated as a community of children, in order to embrace the UU principles most broadly, the concept of community should include others adult visitors, the door keeper - thus reflecting the principles of offering kind treatment to all and membership in the larger community of life on earth. Children from public/traditional school settings familiar with a teacher-driven, behaviorist model of making choices (Freiberg & Lamb, 2009) find the activity of responsible free choice to be strange or unfamiliar. They often await adult direction or ask permission. A period of transition is to be expected to help these children practice looking within to make their choices. Simple strategies by the teacher can help the child look within and decide which activity to choose. The feast component is of grave concern if there are food sensitivities or allergies. This can be addressed by limiting feasting items to water and gluten-free items such as rice

10

SPIRIT PLAY

crackers, or eliminating the feast portion altogether. Typical Sunday morning childrens programs are limited to an hour, thereby leaving very little time after the story telling for free choice activities. Therefore, it is recommended to eliminate those components which may impinge on the time that children have to explore the environment. Certain Sundays may be set aside just for free choice time so that children have ample opportunity to explore materials on a deeper level than the typical 30-40 minutes which may be available after the story telling. Conclusion We are meaning-making creatures. Spirit Play gives language to the existential inquiries of life who we are, what should we be doing with our lives, why are we here. By creating a safe and sacred space for spiritual investigation, and by introducing the language of inquiry i.e., mystery, I wonder, spirit, spiritual practice, covenant and principles or promises, children are trained to seek and to speak their truth in a responsible and meaningful way, and find ways to translate that truth into action and service.

11

SPIRIT PLAY

References Barryman, J. (1995). Teaching Godly Play: The Sunday morning handbook. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press. File, N., Mueller, J. J., Wisneski, D. B. (2011). Curriculum in early childhood education: Re-examined, rediscovered, renewed. Marceline, MO: Walsworth Publishing Company. Freiberg, H. J. & Lamb, S. M. (2009). Dimensions of person-centered classroom management. Theory into practice, 48(99-105). Gutex, G. L. (2004). The Montessori Method. Retrieved from http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/montessori/method/method.html. Haines, A. (2000, July). The role of the teacher and the role of the assistant. Paper presented at the American Montessori International of the United States, Boston, MA. National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2011). 2010 NAEYC standards for initial and advanced early childhood professional preparation programs. Retrieved from http://www.naeyc.org/files/ncate/filenNAEYC%20Initial%20and %20Advanced%20Standars@206_2011-final.pdf. Penfold, N. (2008). Spirit play: A manual for liberal religious education programs. Melrose, MA: Nita Penfold. Stephenson, S. M. (2000). Child of the world: Essential Montessori age 3-12+ years. Arcata, CA: Michael Olaf Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher mental processes. Cambridge, MD: Harvard University Press.

12

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

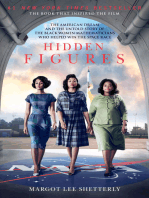

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Treinamento Sap Apo Planejamento de FornecimentoDocument103 pagesTreinamento Sap Apo Planejamento de FornecimentoAntoniniPas encore d'évaluation

- Balancing of Rotating Masses ReportDocument17 pagesBalancing of Rotating Masses Reportwhosamiruladli100% (1)

- How and Why Did The Art and Visual Culture of The Netherlands Differ From That of Other European Countries During The Seventeenth Century?Document4 pagesHow and Why Did The Art and Visual Culture of The Netherlands Differ From That of Other European Countries During The Seventeenth Century?FranzCondePas encore d'évaluation

- D O No. 2, S. 2013-Revised Implementing Guidelines and Regulations of RA No. 8525 Otherwise Known As The Adopt-A-School Program ActDocument15 pagesD O No. 2, S. 2013-Revised Implementing Guidelines and Regulations of RA No. 8525 Otherwise Known As The Adopt-A-School Program ActAllan Jr Pancho0% (1)

- Brown Bear Brown Bear Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesBrown Bear Brown Bear Lesson Planapi-291675678Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bruce Altshuler's The Avant-Garde in Exhibition - New Art in The 20th Century by Saul OstrowDocument2 pagesBruce Altshuler's The Avant-Garde in Exhibition - New Art in The 20th Century by Saul OstrowMariusz UrbanPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic Planning ManualDocument56 pagesStrategic Planning ManualELMUNTHIR BEN AMMAR100% (2)

- Becoming An Adaptive Leader PDFDocument8 pagesBecoming An Adaptive Leader PDFPau Sian LianPas encore d'évaluation

- Frey Violence Terrorism and JusticeDocument17 pagesFrey Violence Terrorism and JusticeJakob StimmlerPas encore d'évaluation

- Seminar ReportDocument38 pagesSeminar ReportRakesh RoshanPas encore d'évaluation

- q2 English Performance TaskDocument1 pageq2 English Performance TaskCHEIRYL DAVOCOLPas encore d'évaluation

- The Theatre of The AbsurdDocument16 pagesThe Theatre of The Absurdbal krishanPas encore d'évaluation

- Case StudyDocument3 pagesCase StudyMa. Fe Evangeline SaponPas encore d'évaluation

- Japanese Narratives and Human Rights Essay (LICCIARDI)Document9 pagesJapanese Narratives and Human Rights Essay (LICCIARDI)licciardi.1789022Pas encore d'évaluation

- Business Plans and Marketing StrategyDocument57 pagesBusiness Plans and Marketing Strategybeautiful silentPas encore d'évaluation

- Management StyleDocument3 pagesManagement StyleNaveca Ace VanPas encore d'évaluation

- Hellenistic CosmologyDocument2 pagesHellenistic CosmologyDelores WeiPas encore d'évaluation

- CASE: A Tragic Choice - Jim and The Natives in The JungleDocument1 pageCASE: A Tragic Choice - Jim and The Natives in The JungleCatherine VenturaPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Journal Review: Bilingual Physic Education 2017Document6 pagesCritical Journal Review: Bilingual Physic Education 2017febry sihitePas encore d'évaluation

- Descriptive QualitativeDocument15 pagesDescriptive QualitativeNeng IkaPas encore d'évaluation

- Vlastos, Equality and Justice in Early Greek CosmologiesDocument24 pagesVlastos, Equality and Justice in Early Greek CosmologiesJocelinPoncePas encore d'évaluation

- No StoneDocument15 pagesNo StoneRachel EscrupoloPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Wushu - IWUFDocument5 pagesHistory of Wushu - IWUFStanislav Ozzy PetrovPas encore d'évaluation

- The Mystery of The TrinityDocument2 pagesThe Mystery of The TrinityChristopher PepplerPas encore d'évaluation

- Edited DemmarkDocument35 pagesEdited DemmarkDemmark RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Hodson, Geoffrey - Angels and Archangels (Art)Document3 pagesHodson, Geoffrey - Angels and Archangels (Art)XangotPas encore d'évaluation

- Common Syllabus of Research MethodologyDocument3 pagesCommon Syllabus of Research MethodologyYogesh DhasmanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 3Document20 pagesUnit 3Cherrypink CahiligPas encore d'évaluation

- British Politics TodayDocument13 pagesBritish Politics TodaySorin CiutacuPas encore d'évaluation

- Overcoming Anthropocentric Humanism and Radical Anti-Humanism: Contours of The Constructive Postmodernist Environmental EpistemologyDocument58 pagesOvercoming Anthropocentric Humanism and Radical Anti-Humanism: Contours of The Constructive Postmodernist Environmental Epistemologyacscarfe2Pas encore d'évaluation