Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Colin Baker

Transféré par

waswalaDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Colin Baker

Transféré par

waswalaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Evaluation & Research in Education Vol. 24, No.

1, March 2011, 4159

Adult language learning: a survey of Welsh for Adults in the context of language planning

Colin Bakera*, Hunydd Andrewsb, Ifor Gruffyddc and Gwyn Lewisb

School of Education, Bangor University, UWB, Holyhead Road, Bangor LL57 2PZ, UK; ESRC Bilingualism Research Centre, Bangor University, Bangor, UK; cNorth Wales Welsh for Adults Centre, Bangor University, Bangor, UK

b a

(Received 28 April 2010; nal version received 19 September 2010) This article discusses the importance of adult language learning when a minority language is threatened. Language acquisition planning attempts to reproduce the language across generations. The research context is Wales with its strong history of adults learning Welsh. The history of the Welsh language shows a decline in the last century, but increased emphasis on language acquisition planning, including adults learning Welsh, has halted the decline. Using a longitudinal design and a multi-method approach, the research aims to understand learners expectations, experiences, outcomes and course issues such as retention and progression. The article reports the initial results from a sample of 1061 adults beginning to learn Welsh, obtained using questionnaire survey methodology. The results suggest that there is a match between the motivations and aspirations of adult language learners and the theory of language acquisition planning. Integrative motivation was stronger than instrumental motivation in commencing the Welsh languagelearning course, although both motivations were present and can be regarded as conceptually but not necessarily psychologically separate. Managing the expectations of course members to enable higher retention rates was found to be important. Language acquisition planning depends on such learners moving to fluency in the language, and thereby to daily language use. Keywords: adult language learning; language planning; Wales; Welsh language; language revitalisation; adult education

Introduction Part of preserving our planet is sustaining the worlds wealth of languages. Adult language learning is a key component in saving that treasury of languages. This article commences by outlining the current scholarly interest in preserving the worlds endangered languages, and how adult language learning is an important component in language resurrection, language planning and language revitalisation. It then briefly shares the context of the Welsh language, followed by a consideration of Welsh for Adults classes within the context of the Welsh language revival. The research is the initial stage in a longitudinal design that follows adults in language-learning classes for three or more years using a multi-method research methodology. It is the first piece of research in Wales that follows adult learners of Welsh as a second language from Entry-level beginners courses to more advanced

*Corresponding author. Email: eds009@bangor.ac.uk

ISSN 0950-0790 print/ISSN 1747-7514 online # 2011 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/09500790.2010.526204 http://www.informaworld.com

42

C. Baker et al.

courses that develop fluency in Welsh. The research derives from key issues in language planning theory with the aim of monitoring one of the priorities of Welsh language revival.

Theoretical background The exact number of languages alive in the world is disputed. Various estimates range from about 5000 to over 7000 languages (Lewis, 2009; Mackey, 1991; Moseley & Asher, 1994; Nettle & Romaine, 2000; UNESCO, 2009). The dispute is due to the difficulty in defining each separate language (Shohamy, 2006), in differentiating a language from a dialect and especially problems of gathering reliable and valid information about languages in large expanses such as Africa, South America and parts of Asia. There is also disagreement about the number of languages that will soon be extinct. There is, however, growing agreement that many or most of the worlds languages are dying languages (Krauss, 1992; Nettle & Romaine, 2000). Krauss (1992, 1998) estimated that between 20% and 50% of the worlds existing languages are likely to die or become perilously close to death in the next 100 years. Wurm (2001) estimated that 50% of the worlds languages are endangered species. Lewis (2009) classified 516 languages as nearly extinct, that is with just a few elderly speakers still alive. The distribution of those 516 languages is: Africa (46), North and South America (170), Asia (78), Europe (12) and The Pacific (210). Some scholars fear it could be worse. In the long term it is a very realistic possibility that 90% of mankinds languages will become extinct or doomed to extinction (Krauss, 1995, p. 4). This estimated 90% death:10% safe ratio is based on such languages no longer being reproduced among children. That is, a language dies when only elderly people speak the language and it is no longer being transmitted to children in families and school, in particular. Therefore, language planning theory has developed in the last decade to provide a framework for the resurrection and revitalisation of threatened languages (Baker, 2010).

Language planning Language planning attempts to reverse the fortunes of endangered languages by topdown and bottom-up interventions. Language planning theory requires three interdependent interventions (Baker, 2008): status planning (e.g. raising the status of a language within society across as many institutions as possible); corpus planning (e.g. modernising terminology, the standardisation of grammar and spelling); and acquisition planning (language reproduction by increasing the number of speakers and uses by, for example, initiatives with parents, language learning in school and adult language classes). The foundation of language planning is acquisition planning. The intergenerational transmission of a language in the family plus language learning in bilingual or multilingual education is an essential but insufficient foundation for language survival and maintenance (Baker, 2003; Gathercole, 2007; Lambert, 2008; Morris & Jones, 2007, 2008; Shin, 2005). Acquisition planning is particularly concerned with not only language reproduction in the family, but also language production at school (second-language learning).

Evaluation & Research in Education

43

In all minority languages, there are families who use the majority language rather than the minority language with their children, due to e.g. urbanisation, education, employment, status and prestige. If this occurs across two or three generations, the minority language will decline and die. A lack of family language reproduction is a foundational and direct cause of language decline. Language acquisition planning is therefore partly about encouraging parents to raise their children bilingually. In terms of this article, it implies the need for parents to become fluent in a minority language that is under threat and engage in daily usage. Adult language learning, particularly for parents, is therefore one component in language planning interventions. Language acquisition planning also involves learning a second language in education as a means of producing more language speakers (Baker, 2003). Through not only bilingual education, or second- and third-language learning, but also via adult classes (e.g. Ulpan), the potential numbers of minority language speakers can be increased. In terms of this article, adult language learning is a way of increasing the stock of language speakers of a threatened language, not only as parents who transmit that language to their children, but also as employees, for example, to give the language a purpose and function. One major theory of language planning is summarised in a four-part model (Baker, 2010):

Acquisition planning (1) family language reproduction; (2) bilingual education pre-school to university; and (3) adult language learning.

Status planning

(1) institutionalisation e.g. use in local and national government and organisations; and (2) modernity e.g. use on television and WWW.

societal level

Usage/opportunity planning

(1) economic and workplace instrumental; and (2) culture, leisure, sports, social, religious and social networks integrative.

individual level

Corpus planning (1) linguistic standardisation (e.g. by dictionaries, school and TV); (2) public vernacular (clear or plain Welsh). Thus, one element in language preservation and revival is adult language learning. This has been recognised in language revivals (e.g. Israel, Hebrew; Scotland, Gaelic; Ireland, Irish; Spain, Basque and Catalan; New Zealand, Maori; the USA, Native American Indian languages such as Navajo; and not least Welsh in Wales). From the 1970s to the present in Wales, adult language learning rapidly grew in terms of

44

C. Baker et al.

numbers and quality. Wales is now recognised as having among the very best approaches to adult language learning in the world (Baker & Jones, 1998). It is the Welsh context for adult language learning that will now be presented. The Wales adult language-learning context During the last century, the Welsh language declined from around one in every two people in Wales speaking Welsh to one in five. According to decennial censuses, the proportion of Welsh speakers had fallen from 54.4% in 1891 to 20.8% in 1971 (Welsh Assembly Government, 2003; Williams, 2000). Concern about the fate of the language led to what Jones (1999) referred to as a time of linguistic awakening. The 1960s and 1970s saw the beginning of a campaign to safeguard the language and a surge of interest in Welsh classes for adults (Morris, 2000). For example, in 1976 the Council for the Welsh Language had identified adult learners as possible participants in reversing the decline in the number of Welsh speakers (Council for the Welsh Language, 1976). The Welsh Assembly Governments Iaith Pawb: A National Action Plan for a Bilingual Wales (2003) set a target of increasing the proportion of Welsh speakers in Wales by 5% by 2011. Subsequent reports on the provision of Welsh language classes for adults made a clear link between this provision and the potential achievement of the Welsh Assemblys goal (ELWa, 2004; Estyn, 2004; Powell & Smith, 2003; Welsh Language Board, 2004). A network of Welsh for Adults classes was earlier established by various institutions the University of Wales, Further Education colleges, the Workers Educational Association, Local Education Authorities and voluntary organisations (Morris, 2000). The number of courses rose rapidly from 186 in 1971, for example, to 373 by 1974. According to a report by the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth, over 5000 learners attended courses during 1972/1973. Most courses provided once-weekly evening classes (Council for the Welsh Language, 1976). It became apparent, however, that it was important for learners to experience as much contact time as possible with the language (Powell & Smith, 2003). This led to a development which has been described as one of the most significant in the field the establishment of intensive Welsh Wlpan courses (Morris, 2000; Welsh Office, 1984). These courses were inspired by the revival of Hebrew in Israel (Rees, 2000). Following the Second World War, intensive Hebrew Ulpan courses were established in Israel to cater for the large influx of immigrants from different countries. The first Ulpan course was held in 1949, providing 36 hours of lessons a week, with an emphasis on spoken Hebrew (Baker & Jones, 1998). One of the course tutors, Shoshana Eytan, was invited to Wales in 1972 to discuss her experiences, and in 1973 the first Welsh Wlpan course was established in Cardiff. This course offered learners 10 hours of lessons a week, over a period of 10 weeks. The 100 hours contact time with the Welsh language during this relatively short period contrasted sharply with most other Welsh courses at the time, which offered approximately 40 hours of lessons in a year (Rees, 2000). The Wlpan course was considered a great success (Rhys, 1986) and was soon followed by a number of similar courses in various locations in Wales (Rees, 2000). Since then, intensive courses have become the responsibility of Higher Education institutions, on the whole, while once-weekly classes are provided by Further Education Colleges, the Local Education Authorities and others (Morris, 2000; Prosser, 1997).

Evaluation & Research in Education

45

Other important developments in the 1970s included the establishment of intensive residential courses, the first of which was held at the University College in Lampeter during the summer of 1975 (Rees, 2000). The success of this month-long course led to the development of an annual eight-week residential summer course (Powell & Smith, 2003). It was commended in a report by the Welsh Office (1984), which highlighted the importance of residential courses in general for adult learners in Wales. Among other providers of residential tuition was the Nant Gwrtheyrn Welsh Language and Heritage Centre on the Llyn Peninsula. Its first course was held in 1982 (Clowes, 2004). Within less than a decade, thousands of adult Welsh learners had attended the centre (Fforwm Iaith Genedlaethol, 1991). Clowes (2004) and Newcombe (2007) have referred to the centres important role in making fluent speakers of Welsh learners. R. Jones (1993) referred to the 1980s as The Welsh learners decade, due to the rapid increase in the number of adult learners during this period. In the autumn of 1981, for example, 3872 learners attended Welsh courses for adults (Welsh Office, 1984). By 1988 the number of learners had reached 8000 and by 1991 there were 11,000 (Prosser, 1997). This prompted R. Jones (1993) to predict a time when secondlanguage Welsh speakers would outnumber native speakers. By 1994/1995, there were 15,894 enrolments on Welsh courses for adults and within another decade the number had increased again to 25,465 (Newcombe, 2007). Welsh for Adults was described by ELWa (2004) as one of the biggest adult-learning programmes in Wales. A number of factors contributed to the considerable increase in demand for this provision. The Welsh Language Board (1999) described the development of a more positive attitude towards the language in Wales, for example, an increase in the number of parents who were choosing Welsh-medium education for their children, and the corresponding effect on demand for Welsh classes for parents:

Gwelwyd cynnydd amlwg yn y nifer o rieni syn anfon eu plant i ysgolion cyfrwng Cymraeg. [. . .] Rhagwelir y bydd galw cynyddol am wersi gan rieni wrth ir Gymraeg ennill lle amlycach yn y gymdeithas sydd ohoni heddiw. [An evident increase has been seen in the number of parents who send their children to Welsh medium schools. [. . .] It is foreseen that there will be an increasing demand for lessons by parents as Welsh attains a more prominent place in todays society.] (Welsh Language Board, 1999, p. 6)

Developments on a statutory level had a positive impact on the status of the language. The use of Welsh in the workplace gained a higher profile following the Welsh Language Act of 1993, which demanded equal treatment of Welsh and English by public sector institutions (Welsh Language Board, 1999). Clowes (2004) and Mann (2007) agreed that the Language Act had contributed to the increasing interest in Welsh, and Clowes also referred to the impact of the National Assembly for Wales, established following a referendum in 1997. B. Jones (1993, p. 10) argued those the success of language revitalisation partly depended on adult learners: in the restoration of the language, the determining factor is and must be the adult-learning movement. He contrasted adults position and influence within society with those of children, arguing against reliance on the education system for language restoration. However, he underlined the link between language learning among adults and children by recommending the provision of Welsh classes for adults within reach of every primary school in Wales. The rise in interest in Welsh classes for adults

46

C. Baker et al.

corresponded with a rapid increase in the provision of Welsh-medium schooling throughout Wales, even in the most anglicised areas:

Even in Gwent, the most English of the Welsh counties, the growth of Welsh-medium education has been strong and consistent and has acted as a catalyst for Welsh classes for adults. (Jones, 1999, p. 448)

A growing awareness of the advantages of bilingualism also inspired an increasing number of adults of all social backgrounds to learn the language (Jones, 1999). However, the social and political context is not only about the increasing awareness of the plight of the Welsh language, integrative and instrumental motivation to learn a language (Gardner, 1985). There is also a social history of conflict and controversy. Protests by language activists wanting political devolution and language group rights, and parents demanding Welsh-medium education for their children, particularly in urban areas (e.g. Cardiff and Swansea), areas of high immigration of English monolinguals, as well as in heartland areas, have placed pressure on politicians and policymakers to reverse the trends of Welsh language decline. Such protest and activism has stirred the conscience, and occasionally been divisive, but served to place Welsh language learning higher up the priority list of politicians and parents. While adult Welsh language learning has not been controversial in itself, it has nevertheless prospered from revitalisation efforts following protest about the decline of the Welsh language. Despite the undoubted flourishing of Welsh for Adults provision during the second half of the twentieth century, the field has not lacked criticism. Morris (2000) described how the provision evolved rather than developing in a planned manner. He criticised the lack of clear planning by the Welsh Office and, subsequently, the National Assembly for Wales which, he claimed, undermined the development of a comprehensive immersion programme for adults as part of a wider language policy. Morris argued that the success or failure of the Welsh for Adults movement, and thus the struggle to revitalise the language, depended on the approach to language planning in Wales:

The potential for successful language shift reversal in this field is evident as is the potential for resource-draining failure unless these developments are brought about within the context of sensitive and sound language planning. (Morris, 2000, p. 214)

Estyn (2004), Her Majestys Inspectorate for Education and Training in Wales, also called for better strategic planning and increased support at a national level in order to improve the provision of Welsh for Adults throughout Wales. Another aspect which has drawn frequent criticism is the funding of Welsh for Adults. Estyn (2004) noted that a number of aspects of the provision, including staffing and the development of resources, were being significantly limited by funding. Lack of funding was also restricting growth in the sector, and therefore the number of successful adult learners. Several reports highlighted a discrepancy between the funding provided for Welsh for Adults and that allocated to English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL), and called for higher funding for Welsh (ELWa, 2004; Estyn, 2004; Powell & Smith, 2003; Welsh Language Board, 1999, 2004). In addition, a major cause for concern, according to Estyn (2004), was the lack of progression by learners from beginners courses to more advanced levels. Newcombe (2007) and the Welsh Language Board (2004) also drew attention to this,

Evaluation & Research in Education

47

and Estyn (2004) stressed the importance of resolving the issue in order to increase the number of fluent Welsh-speaking adults. Comparisons have been drawn between the teaching of Welsh to adults in Wales and the situation of minority languages in other countries. Several reports have referred to the teaching of Basque to adults in the Basque Autonomous Community (BAC), drawing attention to the BAC government-funded HABE Institute for Adult Literacy and Basquisation (Powell & Smith, 2003; Welsh Language Board, 2004). Statutory support for the Basque language was enshrined in the 1982 Act of Normalisation of the Basque Language (Amorrortu, 2003). As a result of this Act, many civil servants were required to learn Basque and were released from their work on a full-time basis to attend classes at public expense (Gardner, 2000). Basque language classes for adults became very popular during the 1980s, attracting over 100,000 learners during 1986/1987 alone (Baker & Jones, 1998). Morris (2000) pointed out that the strength of the Basque adult language movement lay in HABEs close connection with the BAC governments Department of Culture. He contrasted this situation with the devolvement of responsibility for Welsh for Adults to quasi non-governmental organisations in Wales. Powell and Smith (2003) compared learner contact time in both countries and pointed out that the average Welsh learner spent less time in weekly classes (up to 6 hours) than the average Basque learner (at least 10 hours). Estyn (2004) noted that the funding of Welsh for Adults compared unfavourably with that of other minority languages. In 2006, the Welsh Assembly Government announced the establishment of six new regional Welsh for Adults centres, with an investment of 4.6 million over 28 months. A further three-year investment of almost 6.8 million was made in 2008. This can be compared with the annual budget for teaching Basque to adults, which in 2002/2003 was t27 million (Powell & Smith, 2003). In the same way that those in the field of Welsh for Adults look to other countries for inspiration, others look to Wales. Newcombe (2007), for example, described a visit by Gaelic teachers to Wales in 1994. Developments in Wales, therefore, can be considered of international significance. Given the importance of adult learners in the context of language revitalisation, it is essential that large-scale, longitudinal research is carried out in order to effectively inform the further development of Welsh for Adults and the field of adult language learning as a whole. It is in this context that the research project described below is situated.

Research methodology Overview The overarching aim of the research is to study adult language learners of Welsh in all the six districts of North Wales starting Entry-level beginners courses in 2008/ 2009 and 2009/2010. Through a multi-method approach of structured questionnaires, focus groups, observation and interviews, the research aims to discover the effectiveness of various teaching styles and different types of provision, to identify learners experiences and expectations, and to study progression, retention and language proficiency and use. To achieve this aim, the research design is longitudinal, with students commencing courses from 2008 to 2010 being followed through for three or more years. This appears to be the first longitudinal study of adult language learners of Welsh in Wales. This article reports the initial findings of the research

48

C. Baker et al.

analysing the first questionnaire survey. It focuses on learners personal and social characteristics, and particularly on their expectations and reasons for learning Welsh. Survey methodology In the six districts/counties of North Wales, (Anglesey, Gwynedd, Conwy, Denbighshire, Flintshire and Wrexham) there are 11 providers of courses for learning Welsh as an adult (e.g. Further Education Colleges). From late 2008 to early 2010, all such learners were targeted. Thus the whole population of Welsh language adult learners was included rather than a sample. Specifically, a questionnaire was given to all adult Welsh language learners throughout North Wales at the start of beginners courses from September 2008 to January 2010. The questionnaire was developed as follows. It was initially compiled by adapting some questions from existing adult language-learning survey questionnaires, including those used for student evaluation purposes in Wales and beyond. Language use surveys were also reviewed, particularly the Welsh Language Boards 2004 Welsh Language Use Survey and the UK National Student Survey (NSS). The research team also invented new questions to fit the aims of the project. The initial drafts were then refined by being sent for evaluation and feedback to local course leaders, regional Centres and national stakeholders, e.g. the National Assembly for Wales, and to language-learning experts in the UK and Europe. In July 2008, the questionnaire was piloted with a focus group of adults (n06 beginners) who were attending Bangor Universitys summer courses for Welsh learners. The participants were asked to complete the questionnaire at home and then to discuss it in a focus group lasting close to 1 hour. Following this, the questionnaire was redrafted and finalised, and distributed to the population of respondents from September 2008. In terms of protocol, the questionnaire was distributed by tutors during the first lesson of each course. The forms were collected during the same lesson, sealed in an envelope in the presence of the learners to ensure confidentiality, and returned to the research team. The questionnaire asked learners about their previous experience of Welsh for Adults, their current knowledge of Welsh, their reasons for learning the language and their expectations of the course. It also requested personal details such as gender, date and place of birth, time spent living in Wales, educational background, experience of Welsh in education and the use of Welsh in the family. Sample While all adult language learners in North Wales were targeted from September 2008 to January 2010, not all questionnaires were returned. While tutors who distributed the questionnaires during their lessons obtained maximal response, not all tutors and providers distributed the questionnaires. While initial agreement had been obtained with all providers, for pragmatic reasons, not all of the population of adult language learners were given the forms. Details about this are given below. However, this raises the issue of generalisation and whether the respondents are representative of those language learners who were not given the questionnaires to complete. The answer regarding generalisation is quite positive. Given that the whole population of language learners were targeted and not a purposive or convenience sample, results should have been fully generalisable. However, non-response was due

Evaluation & Research in Education

49

to imperfect engagement by providers and tutors, and not due to non-cooperation by respondents. While there were geographical variations in imperfect engagement, nevertheless, individual and social characteristics such as gender, age and previous Welsh language-learning experiences are unlikely to be different between respondents from different locations. Therefore, we are reasonably content that generalisation is possible across the population of language learners in North Wales. Beyond North Wales, no generalisation is possible, and generalisation will require the research being extended throughout Wales, and the research tools being used in other adult language-learning contexts in other countries. In 2008/2009, the total population of Welsh adult language learners in North Wales was 1350. Due to imperfect engagement by some providers, 773 questionnaires were returned (57.3% response rate) rather than 1350. To attempt to increase the number of returns, 555 extra adult language learners were targeted in 2009/2010 to attempt to balance previous imperfect engagement. Limited success was apparent, as from the 555 targeted number, 288 were returned (51.9% response rate). Thus in total, the targeted population was 1905, with 1061 adults completing questionnaires (55.7%). Of those who returned the questionnaire, 69.3% are female and 30.7% male. When asked about their previous experience, 28.2% of learners replied that they had attended a previous course and 13.6% that they had started but not completed a course. The majority of learners (58.7%) were born in England, while close to a third (32.3%) were born in Wales. It is important to note that only 13.2% had not studied Welsh before. Partly due to the Welsh language being compulsory in the National Curriculum of Wales (age 516), many in the sample had previous experience of Welsh language learning. For example, 31.3% of respondents had learnt Welsh in primary school, either before the National Curriculum was implemented or after. The following tables indicate learners length of residence in Wales, their experience of Welsh in education and their highest qualifications, and provide some indication of the nature of the sample (Table 1). Research results To ascertain the match between language planning theory and personal reasons for learning Welsh, respondents were asked Why did you decide to learn Welsh? with 22 sub-dimensions. This question basically seeks to elicit the motivation for joining an adult language course with an underlying conceptual framework partly based on Gardners (1985) research on instrumental and integrative motives for language learning. Instrumental motivation is basically utilitarian in nature. Adult language learners may wish to acquire a second language for employment, promotion or status, for example. In comparison, integrative motivation is more about joining in and identifying with the target languages social and cultural activities. However, some individuals motives may be both instrumental and integrative (e.g. assisting their children in bilingual schooling). Research on integrative and instrumental motivation tends to link the former with a greater likelihood of becoming fluent in the language, and claims it is more long-lasting since it concerns friendships and longerterm relationships rather than short-term economic goals (Baker, 1992; Figure 1). The results suggest that adult language learners are strongly motivated by language reproduction in the family, thus supporting language planning theory. Over

50

C. Baker et al.

Background prole of the sample. Percentage (%)

Table 1.

Years living in Wales B1 12 34 56 7' Learnt Welsh in school Pre-school Primary school Pre-ordinary level/GCSE Ordinary level/GCSE Advanced level Degree None Highest qualification Ordinary level/GCSE Advanced level Degree Higher degree Professional qualification Other

15.3 9.6 9.3 6.4 59.3 13.2 31.3 26.4 15.1 0.5 0.3 13.2 23.2 11.7 30.6 11.4 17.9 5.2

60% of respondents indicate that helping their children with their homework, and speaking to their children in Welsh are major motivations for language learning. In general, integrative motivation appears stronger in this sample than instrumental motivation, with integration into Welsh-speaking communities close to the top of this rank ordered graph. It is noticeable that adult language learning is weakly connected with expressed needs to access mass media in Welsh. Relatively low percentages of respondents indicated that learning Welsh to access Welsh television and radio, or print and electronic media is important to them. For language planning, mass media gives status to a language, yet it results in a more passive connection to the language. In particular, actively speaking a language rather than passively listening to a language is needed for the transmission and reproduction of a language across generations. Another way of testing out whether language planning theory matches personal histories and experiences is to evaluate why respondents had not completed a previous course. For language planning to be successful, non-retention should ideally relate to temporary, short-term and instrumental reasons rather than longer term issues about commitment, motivation and integrative purposes. While this question was relevant to only 138 respondents (as others were commencing their first Welsh language learning course or had completed a previous course), the question also has practical value in terms of retention strategies for such courses (Figure 2). The results suggest that non-retention is partly due to personal circumstances such as other commitments and lack of time. Self-perceptions regarding nonretention also relate to the course itself. Around a fifth of respondents found the language difficult to learn, or the pace of the course too fast, experiencing slow progress and a lack of self-confidence. Such self-perceptions relate to expectations

Evaluation & Research in Education

To help my children with homework Moved to Wales To speak with my children Interest in the language Moved to a Welsh-speaking community To integrate into my local community To improve general skills or knowledge To speak with other family members To speak with work clients or customers Other To speak with my friends To feel more Welsh To improve career prospects To participate at my local school To help gain employment To speak with work colleagues A requirement of my current job To gain a qualification To watch Welsh TV To read Welsh newspapers or magazines To read Welsh websites To listen to Welsh radio

51

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Percentage

Very important Important

Figure 1.

Reasons for learning Welsh.

about the course, and send a clear signal to course providers that such expectations need to be educated and managed for retention and completion. What were the expectations of respondents? For language planning theory, it is important that course members want to be active speakers and transmitters of the language, and use the language in family and other social contexts. In contrast, although far from unimportant, speaking correctly and passively experiencing the language in the media are less important in the reproduction of language across generations (although these are important for the status of a language). The posed question was: By the end of this course, which of the following do you think you will be able to do? (Please tick as appropriate) (Table 2). The ordered table below indicates that among the 10 sub-dimensions, there were four major expectations: to be able to greet people, engage in small talk, pronounce in Welsh and understand simple conversations. There was much less expectation to engage with Welsh language mass media. Given that this referred to Welsh language beginners courses, with more intermediate and advanced courses to follow if desired, then participating in extended conversations might be considered an example of over-expectation with a chance of disappointment and non-retention. Finally, a match between language planning theory and adult language learning prioritises the transmission of Welsh from adults to children. While every encouragement must be given to people of any age to learn a minority language, language revival depends on the language being reproduced in successive generations of children. Thus, in adult language learning, one major target must be potential

52

Other commitments more urgent Lack of time Welsh a difficult language to learn Learning pace too fast Personal reasons Lack of opportunity to practise Family pressures Didn't progress quickly enough Lack of self confidence Didn't like the teaching method Holding back the class Too much grammar Poor quality tutor Lost interest Too much written work What we learnt wasn't useful Learning pace too slow Lack of objectives to the course Didn't like the tutor Poor quality course material Others in the class holding me back Financial reasons Too far to travel Lack of use of IT Not enough grammar Didn't like some other people in the class Too much oral work 0.0 5.0 10.0 15.0 20.0

C. Baker et al.

Percentage

Figure 2. Reasons for not completing a course.

Evaluation & Research in Education

Table 2. Expectations of the course. Very well Greet people with basic words Make general small talk Pronounce Welsh words Read Welsh newspapers or magazines Take part in extended conversations Understand extended conversations Understand simple conversations Understand Welsh radio programmes Understand Welsh TV programmes Write simple messages 61.7 46.0 41.7 5.6 9.6 11.6 31.6 7.2 7.6 19.9 Fairly well 32.0 37.0 50.6 20.7 26.0 30.4 51.9 21.3 23.1 37.2 Partly 4.4 12.1 6.0 35.9 34.1 38.2 12.4 38.9 41.1 23.7 A little 1.8 4.8 1.6 27.1 21.3 15.6 4.0 26.2 23.3 15.3

53

Not at all 0.1 0.2 0.1 10.6 9.1 4.1 0.2 6.3 4.8 4.0

parents and parents of young children. If such parents become sufficiently competent and confident in that minority language, then transmitting that language to their children enables that language to live in the next generation. Since some course members were in families that were already Welsh speaking, especially children learning Welsh as a second language in school, the posed question asked about context rather than intention. Therefore, this survey asked the question: Which members of your family speak/spoke Welsh? (Figure 3). The results show that the context for learning Welsh is primarily familial. That is, respondents indicated that their context for the learning of Welsh was primarily children (and partners). This indicates that course members are motivated to learn Welsh particularly when they can support their children who often are also learning Welsh. In terms of language planning, this is a most positive and promising result. A less positive result would be a context where grandparents and not children were the Welsh language targets, and where language usage would be with a previous rather than a new generation.

Multivariate analyses Much of the above analysis argues for separation between instrumental and integrative reasons for language learning, with the latter having a strong link to language planning. This raises the question as to whether a latent variable analysis of the 22 items that were given as a reason for commencing an adult language-learning course would locate those two conceptual categories as separate or interlinked. Therefore, the 22 items were entered into an exploratory factor analysis to locate the underlying dimensions. Principal axis factoring was used as the method of extraction, with Varimax with Kaiser normalisation as the rotation method. While oblique Direct Oblimin and

54

C. Baker et al.

Child 1 Child 2 Partner Child 3 Grandfather Grandmother

Speaks/spoke fluently

Father in law Mother in law Mother Father Sister Brother 0.0 10.0 20.0 30.0 40.0

Speaks/spoke a little

50.0

60.0

70.0

Percentage

Figure 3. Family members who speak/spoke Welsh.

Promax rotations were run, the factor structure and order of factors on these three different types of rotation were identical. Due to a few of the oblique factor loadings being greater than one, the Varimax solution is reported. The KaiserMeyerOlkin measure of sampling adequacy gave a high coefficient of 0.85 while Bartletts Test of Sphericity was statistically significant at the pB0.0001 level. The following table provides the results of a four factor solution (as indicated by a Scree Test with the eigenvalues of all four factors being over 1.0). The percentage of the total variance explained by these four factors was 48.5% (Table 3). The rotated solution extends beyond a simple instrumental/integrative division. The first latent variable concerns an expressed desire to engage with Welsh mass media (e.g. TV, radio, print and websites). Thus the high loadings indicated in bold print in the table below denote an interest in Welsh mass communication services. The second latent variable has seven high loadings (above 0.35) and relates to wanting to learn Welsh for employment, career prospects, gaining a qualification/skills/knowledge and speaking Welsh with work colleagues, clients and customers. This dimension relates to the instrumental motivation for adult language learning. A third latent variable contains four high loadings expressing a desire to learn Welsh to speak to ones own children, help them with their homework, participate in a local school and speak Welsh to other family members. This relates to the integrative motivation for language learning, with the family at the forefront. This reveals that one dimension in such motivation connects with minority language

Evaluation & Research in Education

Table 3. Varimax rotated factor matrix. Factor Reason for learning Welsh Moved to Wales Moved to a Welsh-speaking community To feel more Welsh To integrate into my local community Interest in the language To gain a qualification To improve general skills or knowledge To help gain employment To improve career prospects A requirement of my current job To speak with work colleagues To speak with work clients or customers To participate at my local school To help my children with homework To speak with my children To speak with other family members To speak with my friends To watch Welsh TV To listen to Welsh radio To read Welsh newspapers or magazines To read Welsh websites Other reason 1 0.064 0.027 0.239 0.143 0.257 0.207 0.218 0.069 0.020 0.093 0.128 0.128 0.170 0.042 0.063 0.225 0.339 0.810 0.860 0.833 0.783 0.255 2 0.024 0.118 0.134 0.118 0.183 0.501 0.396 0.772 0.836 0.600 0.548 0.527 0.230 0.153 0.142 0.246 0.173 0.083 0.107 0.150 0.205 0.192 3 0.041 0.066 0.110 (0.002 0.110 0.155 0.070 0.116 0.083 0.132 0.145 0.192 0.592 0.874 0.884 0.470 0.231 0.155 0.070 0.078 0.071 0.163 4 0.648 0.616 0.411 0.658 0.424 0.068 0.222 0.106 0.049 0.022 0.205 0.214 0.091 0.023 0.068 0.206 0.322 0.138 0.143 0.155 0.142 0.165

55

transmission in the family, which is a key element in language planning. The fourth dimension contains four relatively high loadings (above 0.3) and relates to learning Welsh to identify with a Welsh-speaking community, to feel more Welsh, to integrate into the local community, to speak with friends and out of an intrinsic interest in the language itself. This is another integrative dimension in adult language learning. It refines thinking about the integrative dimension, separating the nuclear family from wider social networking, including in the community. Detailed analyses were made of factor scores compared with the individual and social characteristics by extensive correlation analyses. Such analyses showed no statistically significant differences on the four dimensions based on age, gender, language background or educational qualifications. Kendall non-parametric correlations between age/gender/educational qualifications with the four latent variables (12 correlations in all) ranged between zero and 0.14. Such dimensions appear relatively generalised across adult language learners of different background characteristics. This suggests that the four major dimensions for commencing a course are not specific to particular categories of people.

56

C. Baker et al.

Discussion This article has focused on the necessity of adult language learning relating itself to theoretical notions in language planning. This is a global issue for all minority languages in the world and not just Welsh. The following discussion therefore aims to relate to adult language learning in any country or context. Adult language learning can be valuable for a kaleidoscope of excellent reasons (e.g. accessing the culture of that language, mental stimulation, social networking, travel and vacations, employment and promotion, religious participation, identity and community networking). Each of these reasons makes adult language learning purposeful, worthwhile and beneficial. On an individual basis, each reason provides justification for the supply of adult language learning, plentiful provision, highquality teaching and learning and successful outcomes in terms of fluency and usage. In terms of society, and particularly in terms of the preservation of the rich treasury of the worlds languages and cultures, adult language learning is an important component in language planning. Given that language planning, as a foundation, requires the acquisition of a threatened language by children, parents and others who will transmit that language to successive generations, adult language learning enables such acquisition. Not exclusively, but importantly, parents and teachers who will reproduce the language in children so that language can survive across a few generations, are arguably the most important members of adult language-learning classes. This survey, designed as the first stage in a longitudinal design that will follow course members from beginners classes to the more advanced classes, was driven by two ambitions. First, course providers and teachers need to know the motivations and expectations of their clientele. Knowing their motivations and expectations, contexts and profile, enables a course to be appropriately presented, with needs, hopes and desires kept in mind. Second, and the rationale for this article, such courses are considerably subsidised by the public purse, and this can be well defended by the need for language revival and revitalisation. Given that such courses are one building block in language planning, then elements of language planning theory need to influence, even match, course provision, policy and practice. The motivations and expectations of course members are important so as to test whether language planning needs are paralleled to those reasons for attending the course. This is a topic wherever adult language learning takes place, irrespective of whether it is Maori in New Zealand, Gaelic in Scotland or Navajo in the USA. The results of the research indicate that a particularly positive match occurred between the motivations, personal contexts and aspirations of adult language learners questioned in this survey. A positive match will occur when foundational tenets of language planning theory parallel course members reasons and expectations for learning a minority language as an adult. It is argued that a foundational tenet is language acquisition planning. Such acquisition planning stresses the quintessential nature of parents passing on the language to their children in the family (as well as schooling increasing the stock of language speakers). On four indices in the research, this parallelism occurred. First, the expressed reasons for learning Welsh were predominantly integrative in nature, with speaking to children in the family and helping them with their homework given as important reasons for attending the course. Such reasons tended to be rated as more important than community, career, employment and mass media usage. Generally, longer term

Evaluation & Research in Education

57

integrative reasons predominated over shorter term instrumental reasons. While utilitarian reasons are important for example, that the minority language is linked to the economy such reasons may be less long-lasting than integrative reasons. Such instrumental reasons were given less prominence in responses. However, there is a danger in separating integrative and instrumental motivations. There are reasons why parents invest time and effort in raising their children to be speakers of a minority language. While identity, community engagement, social networking, culture and leisure are all important, nevertheless the links between a minority language and employment rather than economic marginalisation, affluence rather than poverty, career prospects rather than career stagnation, require a minority language to be connected with a language economy. Parents will question why they should bring up their children in a minority language and send them to heritage language education. Part of the answer has to be that there is economic value to learning the language, and this occurs in other minority language contexts such as Basque in Spain and Irish in Ireland. In the same way, parents and teachers in any minority language context need a strong basis for using the minority language in classroom content-learning and not just for second-language learning. While national identity, community and cultural language usage, mental stimulation and preservation of heritage may be good reasons for minority language education, the connection between language learning in school and employment, affluence and career prospects makes minority language learning attractive to children and their parents. That is, for parents to transmit a minority language to their children, utilitarian reasons as well as integrative reasons may be an important part of the rationale. Motivation for language learning exists in terms of complexity and interaction, is something that tends to not be easily observed from a survey questionnaire, and in this longitudinal research it will be further examined by focus groups and interviews. Second, the review of literature noted that retention on such adult languagelearning courses is problematic. Course members start with the best of intentions, the highest of motivations and the most enthusiastic of expectations. Yet language learning takes years rather than days, continuous practice rather than short lessons and commitment across time rather than quick wins. The dropout rate therefore can be high even when a good teaching style, environment, classroom ethos and high-quality materials and excellent staff are present. The analysis of reasons for not completing a previous course indicated that expectations may have been too high, variously in terms of expected time commitments, speed of learning and the need to practise. For language planning purposes, this result suggests that increased clarity is needed at the commencement of a course regarding the amount of progress likely to be made, specific waypoint targets, pragmatic rather than idealistic expectations of fluency, and the need and opportunity to practise between lessons. If expectations are not managed, retention rates may be low, and hence language planning targets to increase the minority language population may become compromised. A third result indicated that most were realistic in terms of restricted outcomes from a beginners course, and that result gives some optimism for language planners who need retention to be as high as possible. The fourth result indicated that the context in which many course members operated was with their children who were also learning Welsh. Given the crucial nature of minority language transmission in the family in language planning theory, this result is most positive. If the minority language is being learnt to speak to grandparents or the

58

C. Baker et al.

extended family, then that is most desirable. However, when the language is learnt to aid the reproduction of the language in children, the future of the language is much more secured, in the family, in society and in any nation across the world. Acknowledgements

The support of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), the Higher Education Funding Council for Wales and the Welsh Assembly Government is gratefully acknowledged, as this research derives from their funding of the Centre for Research on Bilingualism in Theory and Practice at Bangor University.

References

Amorrortu, E. (2003). Basque sociolinguistics: Language, society and culture. Reno, NV: University of Nevada. Baker, C. (1992). Attitudes and language. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. Baker, C. (2003). Language planning: A grounded approach. In J.-M. Dewaele, A. Housen, & L. Wei (Eds.), Bilingualism: Beyond basic principles (pp. 88111). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. Baker, C. (2008). Postlude. Multilingualism and minority languages: Achievements and challenges in education. AILA Review, 21(1), 104110. Baker, C. (2010). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism (5th ed.). Bristol: Multilingual Matters. Baker, C., & Jones, S.P. (1998). Encyclopedia of bilingualism and bilingual education. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. Clowes, C. (2004). Nant Gwrtheyrn. Talybont: Y Lolfa. Council for the Welsh Language. (1976). Welsh for adults: Report to the Right Hon. John Morris. Cardiff: HMSO. ELWa. (2004). Cymraeg i Oedolion: Dogfen ymgynghori ar ailstrwythuro Cymraeg i Oedolion 2004 [Welsh for Adults: A consultation document on restructuring Welsh for Adults 2004]. Cardiff: Author. Retrieved from http://www.elwa.org.uk/doc_bin/bilingual/ncc0412blnal_w_.pdf Estyn. (2004). The quality of provision in Welsh for Adults. Cardiff: Author. Retrieved from http://www.new.wales.gov.uk/docrepos/40382/4038232/403821/196449/Welsh_for_Adults_ report.pdf ?lang 0cy Fforwm Iaith Genedlaethol. (1991). Strategaeth iaith 19912001 [Language strategy 1991 2001]. Caernarfon: Author. Gardner, N. (2000). Basque in education in the Basque Autonomous Community. VitoriaGasteiz: Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia. Gardner, R.C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning. London: Edward Arnold. Gathercole, V.C.M. (Ed.). (2007). Language transmission in bilingual families in Wales. Cardiff: Welsh Language Board. Jones, B. (1993). Language regained. Llandysul: Gomer. Jones, R.O. (1993). The sociolinguistics of Welsh. In M.J. Ball & J. Fife (Eds.), The Celtic languages (pp. 536605). London: Routledge. Jones, R.O. (1999). The Welsh language: Does it have a future? In R. Black, W. Gillies & R. O Maolalaigh (Eds.), Celtic connections: Proceedings of the 10th international congress of Celtic studies Volume 1: Language, literature, history, culture (pp. 425456). East Lothian: Tuckwell Press. Krauss, M. (1992). The worlds languages in crisis. Language, 68(1), 610. Krauss, M. (1995). Language loss in Alaska, the United States and the world. Frame of Reference (Alaska Humanities Forum), 6(1), 25. Krauss, M. (1998). The scope of the language endangerment crisis and recent response to it. In K. Matsumara (Ed.), Studies in endangered languages. Papers from the international symposium on endangered languages. Tokyo, November 1820, 1995 (pp. 101112). Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo.

Evaluation & Research in Education

59

Lambert, B.E. (2008). Family language transmission: Actors, issues, outcomes. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. Lewis, M.P. (2009). The ethnologue (16th ed.). Dallas, TX: Summer Institute of Linguistics. Mackey, W.F. (1991). Language diversity, language policy and the sovereign state. History of European Ideas, 13(12), 5161. Mann, R. (2007). Negotiating the politics of language: Language learning and civic identity in Wales. Ethnicities, 7(2), 208224. Morris, D., & Jones, K. (2007). Minority language socialisation within the family: Investigating the early Welsh language socialisation of babies and young children in mixed language families in Wales. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 28(6), 484501. Morris, D., & Jones, K. (2008). Language socialisation in the home and minority language revitalisation in Europe. In P. Duff & N.H. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education, 2nd ed., Vol. 8: Language socialisation (pp. 127143). New York: Springer. Morris, S. (2000). Adult education, language revival and language planning. In C.H. Williams (Ed.), Language revitalisation: Policy and planning in Wales (pp. 208220). Cardiff: University of Wales Press. Moseley, C., & Asher, R.E. (1994). Atlas of the worlds languages. London: Routledge. Nettle, D., & Romaine, S. (2000). Vanishing voices: The extinction of the worlds languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Newcombe, L.P. (2007). Social context and uency in L2 learners: The case of Wales. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. Powell, R., & Smith, R. (2003). Evaluation of the national Welsh for Adults Programme. Swansea: National Foundation for Educational Research. Retrieved from http://www. new.wales.gov.uk/docrepos/40382/4038232/403821/196449/nfer_welsh_for_adults_revie1.pdf? lang 0cy Prosser, H. (1997). Dysgur Gymraeg yn ail iaith i oedolion. In M. Grifths (Ed.), Addysg Gymraeg (2): Casgliad o ysgrifau [Welsh education (2): A collection of writings] (pp. 95 97). Caerdydd: Cyd-Bwyllgor Addysg Cymru. Rees, C. (2000). Datblygiad yr Wlpan. In C. James (Ed.) Cywynor Gymraeg: Llawlyfr i diwtoriaid iaith [Introducing Welsh: A handbook for language tutors] (pp. 2744). Llandysul: Gomer. Rhys, E. (1986). Dysgur Gymraeg fel ail iaith i oedolion. In M. Grifths (Ed.), Addysg Gymraeg: Casgliad o ysgrifau [Welsh education: A collection of writings] (pp. 3337). Caerdydd: Cyd-Bwyllgor Addysg Cymru. Shin, S.J. (2005). Developing in two languages: Korean children in America. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. Shohamy, E.G. (2006). Language policy: Hidden agendas and new approaches. Abingdon: Routledge. United Nations Educational, Scientic and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). (2009). UNESCO interactive atlas of the worlds languages in danger. Retrieved from http:// www.unesco.org/culture/ich/index.php?pg000206 Welsh Assembly Government. (2003). Iaith pawb: A national action plan for a bilingual Wales. Cardiff: Author. Welsh Language Board. (1999). Strategaeth Cymraeg i Oedolion [Welsh for adults strategy]. Cardiff: Author. Retrieved from http://www.byig-wlb.org.uk/Cymraeg/cyhoeddiadau/ Cyhoeddiadau/227.pdf Welsh Language Board. (2004). Strategaeth addysg a hyfforddiant cyfrwng Cymraeg a dwyieithog [Welsh medium and bilingual education and training strategy]. Cardiff: Author. Retrieved from http://www.rhag.net/strategaeth_BIGc.pdf Welsh Ofce. (1984). Dysgur Gymraeg fel ail iaith i oedolion [Teaching Welsh as a second language to adults]. Cardiff: HMSO. Williams, C.H. (2000). On recognition, resolution and revitalisation. In C.H. Williams (Ed.), Language revitalisation: Policy and planning in Wales (pp. 147). Cardiff: University of Wales Press. Wurm, S.A. (2001). Atlas of the worlds languages in danger of disappearing (2nd ed.). Paris: UNESCO.

Copyright of Evaluation & Research in Education is the property of Multilingual Matters and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Research and Information Gathering Task - ED 204 (Group 13)Document106 pagesResearch and Information Gathering Task - ED 204 (Group 13)WERTY ASDFGPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Emotional Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesSocial Emotional Lesson Planapi-582239348100% (3)

- GenMathG11 Q1 Mod4 ExponentialFunctions v3 PDFDocument43 pagesGenMathG11 Q1 Mod4 ExponentialFunctions v3 PDFTin Galias91% (76)

- QUALITATIVE RESEARCH p.1Document83 pagesQUALITATIVE RESEARCH p.1Margaux Lucas100% (1)

- Lenore A. Grenoble Lindsay J. Whaley Saving - Languages An Introduction To Language RevitalizationDocument245 pagesLenore A. Grenoble Lindsay J. Whaley Saving - Languages An Introduction To Language RevitalizationRatnasiri ArangalaPas encore d'évaluation

- PSR Theory Essay FinalDocument9 pagesPSR Theory Essay Finalapi-238869728Pas encore d'évaluation

- Standing On Principles Collected EssaysDocument318 pagesStanding On Principles Collected EssaysSergi2007100% (1)

- Welcome Vincentian-Anthonians To Ay 2021 - 2022Document13 pagesWelcome Vincentian-Anthonians To Ay 2021 - 2022MYKRISTIE JHO MENDEZPas encore d'évaluation

- Multilingual Is MDocument22 pagesMultilingual Is MMeti MallikarjunPas encore d'évaluation

- The Effectiveness of Bilingual Program and Policy in The Academic Performance and Engagement of StudentsDocument10 pagesThe Effectiveness of Bilingual Program and Policy in The Academic Performance and Engagement of StudentsJoshua LagonoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ghana's Bilingual Education Policy: Prospects and Challenges For ESL EducationDocument12 pagesGhana's Bilingual Education Policy: Prospects and Challenges For ESL EducationNancy Henaku100% (2)

- A Global Perspective On BilingualismDocument5 pagesA Global Perspective On Bilingualismpaula d´alessandroPas encore d'évaluation

- 7.multilingualism W EnglishDocument13 pages7.multilingualism W EnglishozgeozPas encore d'évaluation

- New Gaelic Speakers, New Gaels? Ideologies and Ethnolinguistic Continuity in Contemporary ScotlandDocument22 pagesNew Gaelic Speakers, New Gaels? Ideologies and Ethnolinguistic Continuity in Contemporary ScotlandNikolePas encore d'évaluation

- A Global Perspective On Bilingualism and Bilingual EducationDocument2 pagesA Global Perspective On Bilingualism and Bilingual EducationcanesitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ej 1293060Document9 pagesEj 1293060kinzasaherPas encore d'évaluation

- Bilingualizing Linguistically Homogeneous Classrooms in Kenya Implications On Policy Second Language Learning and LiteracyDocument15 pagesBilingualizing Linguistically Homogeneous Classrooms in Kenya Implications On Policy Second Language Learning and Literacyadrift visionaryPas encore d'évaluation

- AGlobalPerspectiveonBilingualism PDFDocument5 pagesAGlobalPerspectiveonBilingualism PDFradev m azizPas encore d'évaluation

- Incorporating The Idea of Social Identity Into English Language EducationDocument29 pagesIncorporating The Idea of Social Identity Into English Language EducationAmin MofrehPas encore d'évaluation

- What Are The Similarities and Differences Among English Language, Foreign Language, and Heritage Language Education in The United States?Document8 pagesWhat Are The Similarities and Differences Among English Language, Foreign Language, and Heritage Language Education in The United States?Luis Alfredo Acosta QuirozPas encore d'évaluation

- Morphosyntactic Knowledge of Clitics by Portuguese Heritage BilingualsDocument19 pagesMorphosyntactic Knowledge of Clitics by Portuguese Heritage BilingualsAntonio CodinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Paper: Multilingual Youth, Literacy Practices, and Globalization in An Indonesian City: A Preliminary ExplorationDocument43 pagesPaper: Multilingual Youth, Literacy Practices, and Globalization in An Indonesian City: A Preliminary ExplorationMegan KennedyPas encore d'évaluation

- Non-Native-Speaker Teachers and English As An International LanguageDocument10 pagesNon-Native-Speaker Teachers and English As An International LanguageHeidar EbrahimiPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 7 and 4Document8 pagesUnit 7 and 4aminulislamjoy365Pas encore d'évaluation

- MTB For RRLDocument38 pagesMTB For RRLLitovic CasillanPas encore d'évaluation

- Minority Languages and Sustainable Translanguaging Threat or Opportunity PDFDocument13 pagesMinority Languages and Sustainable Translanguaging Threat or Opportunity PDFAsierARLPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Language Loss PDFDocument5 pagesWhat Is Language Loss PDFVaneshaPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence-Based Strategies for Fostering BiliteracyDocument10 pagesEvidence-Based Strategies for Fostering BiliteracyMoni AntolinezPas encore d'évaluation

- Childhood Bilingual Acquisition: A Theoretical PerspectiveDocument9 pagesChildhood Bilingual Acquisition: A Theoretical PerspectiveRania SarriPas encore d'évaluation

- Glocalizing ELT: From Chinglish To China English: Xing FangDocument5 pagesGlocalizing ELT: From Chinglish To China English: Xing FangMayank YuvarajPas encore d'évaluation

- The Key To Global UnderstandingDocument33 pagesThe Key To Global UnderstandingEvelaz2014Pas encore d'évaluation

- CLIL: Content Based Instructional Approach To Second Language PedagogyDocument13 pagesCLIL: Content Based Instructional Approach To Second Language PedagogyArinPas encore d'évaluation

- Farr Et Al-2011-Language and Linguistics Compass PDFDocument16 pagesFarr Et Al-2011-Language and Linguistics Compass PDFFareena BaladiPas encore d'évaluation

- Vernacular Language Varieties in Educational Setting Research and DevelopmentDocument51 pagesVernacular Language Varieties in Educational Setting Research and DevelopmentMary Joy Dizon BatasPas encore d'évaluation

- Phonological and Grammatical Similarities Between English and Kurdish Language: Why English Learning Is Easier For KurdishDocument5 pagesPhonological and Grammatical Similarities Between English and Kurdish Language: Why English Learning Is Easier For KurdishilyasatmacaPas encore d'évaluation

- Defining Multilingualism: See Discussions, Stats, and Author Profiles For This Publication atDocument37 pagesDefining Multilingualism: See Discussions, Stats, and Author Profiles For This Publication atNana Alfi KarrilaPas encore d'évaluation

- 10.blossoming in English - Preschool Children's Emergent Literacy Skills in EnglishDocument27 pages10.blossoming in English - Preschool Children's Emergent Literacy Skills in EnglishSharon ValenciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Book Review Analyzes Language Planning and EducationDocument16 pagesBook Review Analyzes Language Planning and EducationPatricio Careaga OPas encore d'évaluation

- Using Bilingual Books To Enhance Literacy Around The World: Peggy Semingson, PHD Kathryn Pole, PHD Jodi Tommerdahl, PHDDocument8 pagesUsing Bilingual Books To Enhance Literacy Around The World: Peggy Semingson, PHD Kathryn Pole, PHD Jodi Tommerdahl, PHDLee Kai ZhuPas encore d'évaluation

- Transmission of Mother-TongueDocument21 pagesTransmission of Mother-TongueSharmeen IsmailPas encore d'évaluation

- Politico-Economic Influence and Social Outcome of English Language Among Filipinos: An AutoethnographyDocument11 pagesPolitico-Economic Influence and Social Outcome of English Language Among Filipinos: An AutoethnographyBav VAansoqnuaetzPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching World Englishes To Native Speakers of English in The USADocument18 pagesTeaching World Englishes To Native Speakers of English in The USALaura AmatoPas encore d'évaluation

- Article - 451-Production-47-1-10-20210512Document11 pagesArticle - 451-Production-47-1-10-20210512AshleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Goriot Unsworth VanHout Broersma McQueen 2020Document34 pagesGoriot Unsworth VanHout Broersma McQueen 2020FabriZio RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- 32Document14 pages32h.khbz1990Pas encore d'évaluation

- Vietnamese Teachers' and Students' Perceptions of Global EnglishDocument14 pagesVietnamese Teachers' and Students' Perceptions of Global EnglishGeorgeChapmanVNPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching English Through Pedagogical Translanguaging by Jason Cenoz and Durk GorterDocument12 pagesTeaching English Through Pedagogical Translanguaging by Jason Cenoz and Durk GorterAngel AguirrePas encore d'évaluation

- Policies of Bilingualism in Other CountriesDocument8 pagesPolicies of Bilingualism in Other CountriesMelodina SolisPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3 BookDocument21 pagesChapter 3 BookNguyen Le Thao Linh VNUISPas encore d'évaluation

- English as Lingua Franca Implications for Teacher EducationDocument12 pagesEnglish as Lingua Franca Implications for Teacher EducationFlor De AnserisPas encore d'évaluation

- L2 Learners' Mother Tongue, Language Diversity and Language Academic Achievement Leticia N. Aquino, Ph. D. Philippine Normal University Alicia, Isabela, PhilippinesDocument21 pagesL2 Learners' Mother Tongue, Language Diversity and Language Academic Achievement Leticia N. Aquino, Ph. D. Philippine Normal University Alicia, Isabela, PhilippinesRachel Dojello Belangel100% (1)

- Using Translation to Highlight Varieties of EnglishDocument25 pagesUsing Translation to Highlight Varieties of EnglishAchwany AjangPas encore d'évaluation

- Factors Influencing Bilingual Parents' Language Choice for Children With Special NeedsDocument16 pagesFactors Influencing Bilingual Parents' Language Choice for Children With Special NeedsARFA MUNAWELLAPas encore d'évaluation

- English Language Teaching in The PeripheDocument29 pagesEnglish Language Teaching in The PeripheDonaldo Delvis DuddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Indigenous Second Language AcquisitionDocument21 pagesIndigenous Second Language AcquisitionizabelufpaPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippines Is A LinguisticallyDocument3 pagesPhilippines Is A LinguisticallyStephaniePas encore d'évaluation

- Benefits of BilingualismDocument5 pagesBenefits of BilingualismYang LiPas encore d'évaluation

- Enhancement of Vocabulary Skills Through Movie WatchingDocument11 pagesEnhancement of Vocabulary Skills Through Movie WatchingMarjorie FernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Language Choice Code Mixing and Code SwitchingDocument10 pagesLanguage Choice Code Mixing and Code SwitchingBagas TiranggaPas encore d'évaluation

- Non Native EnglishDocument8 pagesNon Native EnglishXohaib YounasPas encore d'évaluation

- JNS - 33 - S1 - 97Document25 pagesJNS - 33 - S1 - 97jctabora0909Pas encore d'évaluation

- Urban Language & Literacies: Working Papers inDocument20 pagesUrban Language & Literacies: Working Papers inMubina11Pas encore d'évaluation

- Early Childhood Bilingualism: Perils and PossibilitiesDocument21 pagesEarly Childhood Bilingualism: Perils and PossibilitiesMaulvericKPas encore d'évaluation

- Narrative Report On AchievementDocument1 pageNarrative Report On AchievementJessanin CalipayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Health and Safety Assessment Form and Plagiarism StatementDocument9 pagesHealth and Safety Assessment Form and Plagiarism StatementMo AlijandroPas encore d'évaluation

- Edusoft Teachers GuideDocument38 pagesEdusoft Teachers GuidekpvishnuPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL March 10Document9 pagesDLL March 10Paynor MenchPas encore d'évaluation

- Spiderwoman Theatre challenges colonial stereotypesDocument12 pagesSpiderwoman Theatre challenges colonial stereotypesdenisebandeiraPas encore d'évaluation

- EPortfolio Strategy - Ziang WangDocument13 pagesEPortfolio Strategy - Ziang WangZiang WangPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Strategies for Maldivian ProductsDocument5 pagesMarketing Strategies for Maldivian ProductsCalistus FernandoPas encore d'évaluation

- 3.3. Digital ProtoypingDocument3 pages3.3. Digital ProtoypingM.Saravana Kumar..M.EPas encore d'évaluation

- Course Syllabus & Schedule: ACC 202 - I ADocument8 pagesCourse Syllabus & Schedule: ACC 202 - I Aapi-291790077Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lala National HS Bags 2nd Place at Sagayan Festival & Nutrition Month ReportDocument3 pagesLala National HS Bags 2nd Place at Sagayan Festival & Nutrition Month ReportFeby ApatPas encore d'évaluation

- IIFM Placement Brochure 2022-24-4 Pages Final LRDocument4 pagesIIFM Placement Brochure 2022-24-4 Pages Final LRPushkar ParasharPas encore d'évaluation

- The Cut Off - Short Story by Chetan BhagatDocument7 pagesThe Cut Off - Short Story by Chetan Bhagatshailesh kumar sundramPas encore d'évaluation

- IGCSE Chemistry Work Book by Richard HarwoodDocument97 pagesIGCSE Chemistry Work Book by Richard HarwoodIsmail Balol86% (7)

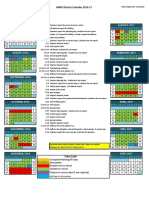

- 2016-17 District CalendarDocument1 page2016-17 District Calendarapi-311229971Pas encore d'évaluation

- Smart Implementation - Intergraph's Latest ApproachDocument4 pagesSmart Implementation - Intergraph's Latest ApproachLogeswaran AppaduraiPas encore d'évaluation

- CBCS Syllabus Ecology FinalDocument49 pagesCBCS Syllabus Ecology FinalRahul DekaPas encore d'évaluation

- Kra #Master TeachersDocument29 pagesKra #Master TeachersMary Joy Catrina AnduyonPas encore d'évaluation

- Sri Ramachandra University Nursing SyllabusDocument9 pagesSri Ramachandra University Nursing SyllabusEric ReubenPas encore d'évaluation

- Models of Religious Freedom FINAL VERSIONDocument572 pagesModels of Religious Freedom FINAL VERSIONMarcel StüssiPas encore d'évaluation

- DownloadfileDocument7 pagesDownloadfileFernanda FreitasPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Physical EducationDocument2 pagesHistory of Physical EducationMay MayPas encore d'évaluation

- Completing-Your-Copy-With-Captions-And-Headlines Lesson-2Document12 pagesCompleting-Your-Copy-With-Captions-And-Headlines Lesson-2api-294176103Pas encore d'évaluation

- O2 Life Skills Module 4 Work Habits Conduct Modular FINAL VERSION 8-13-2020Document64 pagesO2 Life Skills Module 4 Work Habits Conduct Modular FINAL VERSION 8-13-2020Tata Lino100% (4)