Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The Good, The Bad and The Ugly: Specialised Bodies and Racial Discrimination in Britain, 10 Years On...

Transféré par

Prof Kay HamptonTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Good, The Bad and The Ugly: Specialised Bodies and Racial Discrimination in Britain, 10 Years On...

Transféré par

Prof Kay HamptonDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

ABSTRACT: ISS- RC05: RACISM, NATIONALISM AND ETHNICIY Session 10: Racial Discrimination in Europe-10 years on

Name of Author: Professor Kay Hampton Institution: Glasgow Caledonian University TITLE: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Specialised Bodies and Racial Discrimination in Britain, 10 years on It is not enough to have legal protections without

independent, specialised bodies to ensure that peoples rights are being effectively realised. So what happens when specialised bodies become compromised? This paper will reflect on the British experience over the last 10 years, highlighting how protection against racial discrimination, which was in place for over 40 years, is in danger of being diluted by changing political contexts and local power elites. The paper will argue that despite the increase in racial discrimination post 9/11, concerns in this regard is

shadowed by real or imagined threats of terrorism and misconceptions around competing rights. More recently, institutions in Britain have tended to use the economic recession and a belief in notions of a post-race society as reasons for taking a so-called modernising approach towards racial discrimination. So plausable are the arguments, despite it being academically flawed, that even members of racially marginalised communities in Britain are duped into believing that racial discrimination is no longer a problem in Britain. While some argue that the replacement of the CRE1 (established to enforce the Race Relations Act, 1976, 2000) with the British Equality and Human Rights Commission2 is a step in the right direction, others feel that this move has led to a weakening of protection for racial minorities in Britain. This paper will reflect on these developments and conclude that the rights of racial minorities can still be successfully protected via the EHRC but that the body itself needs to demonstrate its independence from political interference. Additionally it must be committed to working in a principled, value driven, even-

Established in 1976 by the Race Relations Act (1976) and given more powers in 2000 by the amended Act (RRAA2000) 2 Was established in 2006 to replace the CRE, DRC and EOC

handed way and to balance competing inequalities and priorities in an evidenced based manner.

1 2 3 4 5 6

The role and significance of Specialised Bodies Independence-Paris principles Achievements to date: CRE legacy: trends in race approaches Is Race no longer an Issue? Evidence of racism A rights based approach to Race

Outline Introduction My presentation is part of a more detailed paper, which reflects on performance of two bodies in Britain tasked with the remit to eradicate racism and promote good race relations. My paper is based on on a much broader study of race and power relations and reflections of my own experience as deputy chair and then chair of one of the bodies, the Commission for Racial Equality. It is very difficult to comment on the state of race equality in Britain, without mentioning the influence of specialised bodies. Together with dedicated legislation, the Race Relations Act, they had a profound impact on shaping race equality in Britain during the last 50 years. Specialised Bodies: CRE In 1976, when much of the world was looking at international peace and non-discrimination, Britain focussed on national

issues of concern (Banton, 2006). So during this year when two human rights covernants (socio-economic rights and civic and political rights), which was re-enforced by the International Convention On all Forms of Racial Discrimination (specialised Treaty) come into force, Britain passed the Race Relation Act (1976) and symultaniously established a Commission for Racial Equality. During this period, there was national unrest, tensions and overt racism directed toward immigrants from ex-colonies and therefore a strong political desire to stabalise the country and demonstrate that thy filfulled their treaty obligation. Not withstanding this, Britain then lead in Europe as one of the first to legislate on Racial Discrimination and to establish a specialised body to oversee the ennforcement of the Law. A key architect of the Race Relations Act, Lester who was strongly influenced by the civic movements in the US, was then a labour Minister and lobbied heavily for its creation. He nevertheless conceded 30 years on that the CRE did not really carry out its mandate in full.

Perhaps its is unrealistic to have expected that they would do do, especially in a context in which the courts tended to doubt their ligitimacy and reviewed their actions excessively strictly when the commission were challenged for using their powers extensively While the jury is still out as to whether or not the CRE was successful in its duties over the last 40 years, I believe that it nevertheless served as a recognised, national voice for race equality and despite its limitations, was highly influencial in certain quarters. In reality, for the majority of its existence, the CRE, despite having very strong leaders technically had its hands tied behind its back. The CRE, by its very nature, was given very limited space and resources to effectively use its legal powers to effect fundamental root and branch change. Some might claim cynically, that this was done more by design than accident and that the CRE was intended to be nothing more than a political statement by the then Government, especially given the internal and external

pressures and tensions it faced, at the time, in regard to race relations. Indeed, you need only to look at the parallel restrictive immigration legislations passed during the same time (which was neatly exempt from the RRA), to realise that this view is perhaps not so far from the truth. Still, despite these early limitations, the Act and the CRE were nevertheless kept alive for over 25 years. No small miracle, and only made possible by the efforts of the likes of a network of RECs who did their best to deliver on race equality at local level through small amounts of funding provided by the CRE and others. Distanced Travelled: progress/regress In reality, and perhaps ironically, the CRE was only able to use its full range of powers, some 28 years after its establishment, which sadly coincided with its final years of existence. And this only became possible through the unprecedented and sustained efforts of grass roots

communities and individuals like the Lawrence Family who stopped at nothing to achieve social justice. The CRE had made several attempts during the previous 25 years to get the Act Amended and failed. So it is my strong belief that had it not been for the personal commitment and persistent efforts of the Lawrence Family, the RRA might not have been amended in 2001. Notwithstanding this and while some still argue that it was too little too late, the advancement made in terms of race equality from 2001 - 2006 cannot be ignored. While public institutions now claim credit for this progress, it was not achieved by goodwill alone as some claim but by raw fear of legal action on the part of public institutions. At community level, The Amended Act provided a new impetus for driving forward race equality and injected renewed energy in community groups that have fought long and hard for equality.

In a nutshell, the CRE was at long last able to be a true enabler, facilitator and enforcer as it now had the necessary powers post-amendment to hold to account over 50,000 public institutions, including the government. In parallel, the CRE had planned to provide legal support and advice for victims of race inequality through enhanced funding for the development and promotion of race equality work across Britain via its partners, the RECs. I think it is important to say that despite certain

dissatisfaction with the proposed approach to outcome funding taken at the time, the strategic investment proposed at the time would have greatly progressed race equality at community level. And alongside this, the implementation of the specific duty at institutional level would have delivered measurable improvement in racial equality year on year. For the record, by the time the CRE closed its doors in October 2007 It had developed and implemented a framework for embedding the race equality public duty

Initiated and started the development of a strong network of voluntary organisations, including the RECs to deliver race equality outcomes at grass roots, with funding through our Section 66 and 44 funding streams

Established

strong

partnership

approach

to

delivering race equality through working closely with inspectorates and local communities Undertook joint initiatives with partners to ensure high quality legal advice for victims of racial abuse. By this time, we had also established a tradition of developing race equality manifestos for political parties to ensure that Race equality was seen as a cross-party issue. The latter was usually based on a comprehensive review of progress on race equality and public sector performance based on intelligence we received from our funded partners.

The demise of the CRE, I believe, has stunted the momentum set by early 2007 POST CRE In considering the future of race equality it is important to consider the position of Government and the institutions established to oversee race equality, ie: the EHRC. These institutions play a significant role in shaping the future of race equality in a post-CRE Britain Government: (and this is the previous one) In a statement released by CLG in January 2010 Ministers take full credit for some of the positive developments and progress made in race equality and reassure us that they are committed to progress this agenda even further.

John Denham, for example, asserts that The government has an absolute commitment to eradicating racism and promoting racial equaliy. And

the work will not stop until every single person in this country has the same apportunities and an equal chance of success In the document, the government also promises that the new Equality Bill will modernise, streamline and strengthen the existing legislative framework (IN REFERENCE TO RRAA), helping people to understand their rights and further reduce inequalities The document goes on to say that it will work closely with EHRC to ensure enforcement of the new integrated equality duty. This, it claims, will encourage public bodies to address the needs of groups experiencing disadvantage and discrimination. The CLG also pledged to set up a Tackling Race Inequalities Fund to support national and regional voluntary sector bodies. Finally, it lists 6 specific tasks for the EHRC in relation to improving race equality. I am not going to go into detail

except to say that while on paper this looks impressive, I remain concerned for several reasons: i) Now that we have had a change in Government: how much of what is intended will definately be delivered-will this change in any way? ii) Although CLG indicates its intention to establish a dedicated pot of funding for addressing racial inequality, they have not specified any detail in terms of amount, priority or how this will be distributed-Is this a National Fund or England only? In a climate of cuts will this fund materialise? iii) Thirdly and more worringly, If you look at the six tasks laid out for EHRC, you will note that the scale and scope of what is expected of EHRC in relation to eradicating and reducing racial inequality is in my view, extremely limited. To illustrate my concern, let me show you what the likely impact will be on one aspect: legal support for victims of racial inequality. The CLG document states that it expects the EHRC to

Undertake at least 100 legal actions within their remit and intervene in at least 70 cases annually to strengthen the protection available for individuals By comparison: In 2002, the CRE (which had a far smaller budget) considered 1300 applications for assistance in legal cases and this does not account for the number of cases handled by RECs In 2005, CRE considered 1,028 applications, slightly down but not by much, nevertheless it was an 85% increase on the previous year. Of those who applied for assistance, over 50% of the applicants: 503 applicants were given full advice and assistance. So who and how will the gap be addressed in the future, especially in light of the evidence that suggests that racial inequality is increasing not decreasing?

Interestingly, in 2005, the chair of the CRE who is now Chair of EHRC, expressed similar concerns: he stated in his annual report: We remain concerned that there was still no obligation for the CEHR to consider every application for assistance from individuals who think they may have been discriminated against, and that race might be diluted in a single organisation He continues: our stake holders, including the RECs and national ethnic minority networks, made a case for a statutory race committee, similar to disability committee that has been agreed, with powers to dispense grants for local race equality work 2005: 6 So Post CRE What is the Response of the EHRC? Many, like myself, were hopeful that the new appointed Chair of the EHRC would reduce some of the anxieties that he himself expressed previously, especially given his acuate

awareness of the unease surrounding the future of race equality, post the establishment of a single body. As feared, the EHRC in effect, did not make provision for a statutory race committee to be established. Indeed, certain developments over past three years, tends to increase rather than reduce the anxieties expressed by many in 2005. Despite high expectations and positive attitudes towards the newly established ECHR, there are still underlying concerns about the ability of the not so new body to deliver the same level of input into race equality, given its new, broader mandate. The nature and size of EHRC, the size of its budget and its broader remit makes it clear that even with the best intentions, the ECHR will in practical terms, be unlikely to invest the required time or resources to address race equality in the manner that the CRE did.

This was re-confirmed for me during my time as Transition Commissioner for Race in the EHRC. My Role, as I understood was to ensure that the EHRC built on the good practice of the CRE so that momentum was not lost in progress. Instead, it became clear from the beginning that there was little desire to do so. Instead there was a strong desire within the EHRC to take, what is refered to, as a non - strand specific approach. And although this has now changed to having board members Champion different equality strands, the outcome of this change is yet to be judged. To make matters worse, the messages that emerge from the EHRC leadership in race equality is often confusing and gives the impression that racial inequality is no longer a major issue of concern, despite evidence to the contrary. For example, The EHRC Chair in a speech to mark the 10th Anniversary of the McPherson findings in January (2010) said this:

If we are considering the attitudes of the majority to the minority, today Britain is by far and I mean by far the best place in Europe to live if you are not white. In another speech he claimed, (in general reference to the British society) We are not racists. How could we be? We are an ancient multilingual state forged from at least four different ethnicities, with a people built on and used to inter-marriage, compromise and negotiation. What do these simplistic statements say to the general public? Moreover, the future of Race equality in Britain is threatened by the conflicting discourse surrounding the issue of race and racism. Post CRE, under a guise of being modernised and streamlined, the notion of racism has all but disappeared from public debates and policies. These days, it is

considered old-fashioned and non-progressive to talk about racism and racial equality, in certain quarters. Instead we use generic terms like disadvantage or discrimination and we are told that institutional racism is a thing of the past and that we are to use the term systemic bias instead! Similarly, it is now more acceptable to speak of

multiculturalism (or its death), identity and identity politics, citizenship and immigration, community cohesion and public safety, integration, segregation and Britishness, - in other words anything but racism or racial inequality. But the serious point here is that by doing this, concerns relating exclusively to racism become shadowed, thus often shutting down debates around the ugly aspects of daily racism and discrimination. This is not helpful. The points I make here are not new:

In 2004 (in McGhee 2008): the current Chair of the EHRC made a similar observation when trying to make a case for retaining a focus on race: It is simplistic to suggest that all forms of

discriminatory treatment are similar, and misleading to suggest that they will all be susceptible to similar remedies So what has changed? And why has the mood music now changed to one where race has once again become a dirty word. Have we become oversensitive and politically correct? Are we crying wolf or is racism and racial inequality really a thing of the past. What are the limits of our acceptance these days? In the same speech marking the 10th Anniversary of the McPherson findings. This is what the EHRC Chair had to say on the use of racial language, which by the way is still as I recall, illegal in terms of the RRAA: Few of us feel that Prince Harry is some kind of racist or homophobic bigot, however ill-judged his choice of

fancy dress costume, however crude and offensive his remarks. But we can see he likes to be one of the boys. And as one of the boys, he operates by the unwritten code of his environment a code that didn't once cause him to question whether calling fellow officers 'Paki', 'raghead' or 'queer' was insulting or inappropriate. So how do we deal with this? I certainly don't think that we need to get bent out of shape about the careless act of one junior officer, however famous he is. The Army's disciplinary system should deal with this, without outside interference. That is why we will not intervene on this case Is this the new meaning of tolerance? Is this the value we place on Race equality today? Call me old fashioned, but I think not! SO WHERE DO WE TURN FOR LEADERSHIP (as we understand it) IN PRESENT DAY BRITAIN?

I know that the picture I have painted so far appears bleak, but I believe it is necessary to acknowledge from a practical point of view where we stand, so that organisations realise that their efforts are needed now more than ever. In the absence of a strong, consistent, national voice, it is imperative that the grassroots organisations take the leadership role and champion race equality in ways that make a real difference to the everyday lives of ordinary people who in their everyday activities still experience racism however subtle. Racism is not necessarily only about measuring how many of us make it to universities or prisons; it is also about the little events that on a daily basis rob people of their dignity and their humanity. Political Inteference: Misuse of Specialised Bodies EHRC: HR or Race Equality: CURRENT STATE OF RACE It is therefore timely to discuss pragmatic and strategic ways in which the work started by the CRE continues and develops. Doing race equality work is not a fashion

statement, its not seasonal thing and has to be addressed through sustained effort. By way of example, allow me to mention some of the key areas of work that might grass roots communities can contribute to. i) Monitoring assessibility progress to Legal on the Public and Duties, to

advice

funding

support for race equality work, nationally and locally. ii) Community Groups must consider taking up their initial role of holding responsible organisations, including the EHRC, to account and to demand annual audits on race equality outcomes iii) They must also consider how best key stakeholders can reclaim ownership of the race agenda and make it work in a manner that is relevant to local Communities.

We need to change this new dangerous culture and environment, which avoids any mention of racism. Racial inequality is not something that can always be simply addressed through projects tackling other related but discrete areas of concerns: like community cohesion, community safety or immigration. Failure to act now, will surely result in the loss of specialised knowledge and expertise gathered over half a century in Britain. The impact of this on the future of race equality does not need mention. While I still support the idea of a single co-ordinated governance framework for equality (in the form of the EHRC), I still have concerns with the approaches taken to address Race equality. The CLG on the other hand, can only succeed in achieving its objective if there is a strong network of diverse, specialised organisations at local levels. These organisations will continue to be the only way in which local

expertise can be captured effectively and put to use for finding local solutions. This leads me neatly to another area and that is funding for race equality work. The grass roots community groups must seek to have a role in shaping the priorities and delivery of the proposed Tackling Race inequalities fund This is necessary if we are to preserve the fragile infrastructure that was established by the CRE towards the latter part of its existance. Finally, in terms of legal support and advice, the early indications are that the recent changes are likely to have an impact on the level of support that might be available for legal work relating to race equality. This concern must be included in any debate linked to the CLG Tackling Race Inequalities Fund. In conclusion, I want to emphasise that, while we can point to a number of advancements in the field of race equality, progress has not been as fast as some might like us to believe. As we all know, it is easy to write policies, devise

impressive strategies, make headline-grabbing statements and tick boxes. These do little to fundamentally change reality. Similarly, changing the language of the debate or higlighting isolated incidence of good practice, while good to encourage, is not enough. Post Mcpherson, it has become far too easy for institutions and government to say much progress has been made, but we cannot remain complacent and then provide a long list illustrating all key areas in which racial inequality still exists, which, in effect, contradicts the claim of progress! While it is good to note that we now have (and I quote Malik, in the CLG statement) ethnic minorities as chief constables, permanent secretaries, High court judges and ethnic minority ministersThese are not necessarily markers of real change on the ground. We must not be duped into believing that individual success necessarily represents widespread progress on race

equality. In any case, being in privileged positions does not necessarily mean that you are immune to racial abuse. We must therefore, continue to openly challenged racial discrimination in all its ugly forms, be it verbal abuse by a prince or the inability of a child to understand why they are picked on a daily basis simply because they look, dress or speak differently. This too is important an area, to allow complacency to set in, or tokenism and rhetoric to blind us. Thank you for listening

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Human Rights and Equalities Scotland - How The New Landscape Affects YouDocument8 pagesHuman Rights and Equalities Scotland - How The New Landscape Affects YouProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Rights and Environmental JusticeDocument2 pagesHuman Rights and Environmental JusticeProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- Experiences of Racism and Racial Harassment in South LanarkshireDocument28 pagesExperiences of Racism and Racial Harassment in South LanarkshireProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- Runnymede Launch: Achieving Race Equality in ScotlandDocument8 pagesRunnymede Launch: Achieving Race Equality in ScotlandProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- From Legislation To Reality: Equal Opportunity and EmpowermentDocument13 pagesFrom Legislation To Reality: Equal Opportunity and EmpowermentProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- Putting Race-Rights Back Onto The Agenda in ScotlandDocument9 pagesPutting Race-Rights Back Onto The Agenda in ScotlandProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- Using Qualitative Methods To Develop and Evaluate A Health Promotion Strategy: Asian and Chinese Women's Health Project in GlasgowDocument8 pagesUsing Qualitative Methods To Develop and Evaluate A Health Promotion Strategy: Asian and Chinese Women's Health Project in GlasgowProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- Leading To Learn, Learning To Lead: The Importance of Leadership and Personal Development For Policing Diverse BritainDocument12 pagesLeading To Learn, Learning To Lead: The Importance of Leadership and Personal Development For Policing Diverse BritainProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- An Evaluation of The Greenspaces Programme For BTCV Scotland - Final ReportDocument99 pagesAn Evaluation of The Greenspaces Programme For BTCV Scotland - Final ReportProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- The Future of Minority Rights in The Context of Social and Global ChangesDocument8 pagesThe Future of Minority Rights in The Context of Social and Global ChangesProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- The Last Chair of The Commission of Racial EqualityDocument2 pagesThe Last Chair of The Commission of Racial EqualityProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- CEMVO Scotland Civic Life BulletinDocument4 pagesCEMVO Scotland Civic Life BulletinProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- Part of The Problem or Part of The Solution? Commissioned Research and The Political Creation of "Race" MeaningDocument13 pagesPart of The Problem or Part of The Solution? Commissioned Research and The Political Creation of "Race" MeaningProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- Achieving Integration in Multicultural SocietiesDocument5 pagesAchieving Integration in Multicultural SocietiesProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- Muslims For Secular Democracy, IndiaDocument12 pagesMuslims For Secular Democracy, IndiaProf Kay HamptonPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Madhuri Economics of Banking Semester 1 ProjectDocument35 pagesMadhuri Economics of Banking Semester 1 ProjectAnaniya TiwariPas encore d'évaluation

- Words and Lexemes PDFDocument48 pagesWords and Lexemes PDFChishmish DollPas encore d'évaluation

- F1 English PT3 Formatted Exam PaperDocument10 pagesF1 English PT3 Formatted Exam PaperCmot Qkf Sia-zPas encore d'évaluation

- "AGROCRAFT (Farmer Buyer Portal) ": Ansh Chhadva (501816) Gladina Raymond (501821) Omkar Bhabal (501807)Document18 pages"AGROCRAFT (Farmer Buyer Portal) ": Ansh Chhadva (501816) Gladina Raymond (501821) Omkar Bhabal (501807)Omkar BhabalPas encore d'évaluation

- Between The World and MeDocument2 pagesBetween The World and Meapi-3886294240% (1)

- Dorfman v. UCSD Ruling - California Court of Appeal, Fourth Appellate DivisionDocument20 pagesDorfman v. UCSD Ruling - California Court of Appeal, Fourth Appellate DivisionThe College FixPas encore d'évaluation

- TallerDocument102 pagesTallerMarie RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

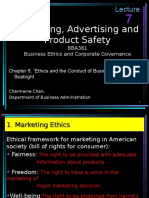

- Marketing, Advertising and Product SafetyDocument15 pagesMarketing, Advertising and Product SafetySmriti MehtaPas encore d'évaluation

- Censorship Is Always Self Defeating and Therefore FutileDocument2 pagesCensorship Is Always Self Defeating and Therefore Futileqwert2526Pas encore d'évaluation

- (Julian v. Roberts) The Virtual Prison CommunityDocument233 pages(Julian v. Roberts) The Virtual Prison CommunityTaok CrokoPas encore d'évaluation

- JAR23 Amendment 3Document6 pagesJAR23 Amendment 3SwiftTGSolutionsPas encore d'évaluation

- Nifty Technical Analysis and Market RoundupDocument3 pagesNifty Technical Analysis and Market RoundupKavitha RavikumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Malayan Law Journal Reports 1995 Volume 3 CaseDocument22 pagesMalayan Law Journal Reports 1995 Volume 3 CaseChin Kuen YeiPas encore d'évaluation

- Software Project Sign-Off DocumentDocument7 pagesSoftware Project Sign-Off DocumentVocika MusixPas encore d'évaluation

- Pattaradday Festival: Celebrating Unity in Santiago City's HistoryDocument16 pagesPattaradday Festival: Celebrating Unity in Santiago City's HistoryJonathan TolentinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Department of Education: Sergia Soriano Esteban Integrated School IiDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: Sergia Soriano Esteban Integrated School IiIan Santos B. SalinasPas encore d'évaluation

- Working While Studying in Higher Education: The Impact of The Economic Crisis On Academic and Labour Market Success (Preprint Version)Document22 pagesWorking While Studying in Higher Education: The Impact of The Economic Crisis On Academic and Labour Market Success (Preprint Version)Vexie Monique GabolPas encore d'évaluation

- Eep306 Assessment 1 FeedbackDocument2 pagesEep306 Assessment 1 Feedbackapi-354631612Pas encore d'évaluation

- Some People Think We Should Abolish All Examinations in School. What Is Your Opinion?Document7 pagesSome People Think We Should Abolish All Examinations in School. What Is Your Opinion?Bach Hua Hua100% (1)

- Cover Letter For Post of Business Process Improvement CoordinatorDocument3 pagesCover Letter For Post of Business Process Improvement Coordinatorsandeep salgadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Activity 4 Theology 1. JOB Does Faith in God Eliminate Trials?Document3 pagesFinal Activity 4 Theology 1. JOB Does Faith in God Eliminate Trials?Anna May BatasPas encore d'évaluation

- NS500 Basic Spec 2014-1015Document58 pagesNS500 Basic Spec 2014-1015Adrian Valentin SibiceanuPas encore d'évaluation

- Student Majoriti Planing After GrdaduationDocument13 pagesStudent Majoriti Planing After GrdaduationShafizahNurPas encore d'évaluation

- Chap1 HRM581 Oct Feb 2023Document20 pagesChap1 HRM581 Oct Feb 2023liana bahaPas encore d'évaluation

- I Am The One Who Would Awaken YouDocument5 pagesI Am The One Who Would Awaken Youtimsmith1081574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Table of ProphetsDocument5 pagesTable of ProphetsNajib AmrullahPas encore d'évaluation

- Personal Values: Definitions & TypesDocument1 pagePersonal Values: Definitions & TypesGermaeGonzalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus For M. Phil. Course Part - I Paper - I Title: General Survey of Buddhism in India and Abroad 100 Marks Section - ADocument6 pagesSyllabus For M. Phil. Course Part - I Paper - I Title: General Survey of Buddhism in India and Abroad 100 Marks Section - ASunil SPas encore d'évaluation

- Special Educational Needs, Inclusion and DiversityDocument665 pagesSpecial Educational Needs, Inclusion and DiversityAndrej Hodonj100% (1)

- WordAds - High Quality Ads For WordPress Generate IncomeDocument1 pageWordAds - High Quality Ads For WordPress Generate IncomeSulemanPas encore d'évaluation