Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

May 20, 2012 P3

Transféré par

NElitreviewDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

May 20, 2012 P3

Transféré par

NElitreviewDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

NELit review

POST script 3

MAY 20, 2012

SEVEN SISTERS

Writing travel

T

HE Assamese word for folktale is xadhukatha. Xadhu appears to have two meanings: one, good and honest, and the other, a travelling/wandering merchant. So one meaning of xadhukatha may be tales told by travelling merchants. As John Zilcosky has suggested (in Writing Travel), storytelling might have begun with travel. Travel writing as a distinctive literary genre did not gain wide academic acceptance till three or four decades ago. Though a number of popular texts related to travel (e.g., The Travels of Marco Polo and The Travels of Sir John Mandeville) were produced during the medieval period, writing became an important aspect of travel in the early days of colonial expansion as it was considered necessary to document what a traveller saw and experienced in order to attract investment in newer locations. During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, English traders and adventurers ventured out to the East and produced a large number of narratives. Richard Hakluyt collected a number of such documents and travel narratives for his The Principal Navigations, Voyages and Discoveries of the English Nation (1589) which provided useful information to the East India Company. Travel writings produced in the 19th century offer insight into the operation of colonial discourses. Representations of societies and cultures found in such writings often help to critically examine the relationship of culture and power. In recent times, womens travel writing, especially of the colonial period, has assumed importance in view of the insights such writing can offer into various issues relating to gender, power and colonialism. Thus, travel writing need not remain just as a form of popular and entertaining literature but may be quite serious and subtle, offering direct and meaningful engagement with social, cultural and political issues. Though the Northeast was not a popular tourist destination in the past, commercial interests and, on rare occasions, a spirit of adventure led a small number of foreigners to visit this region. One of the earliest European travellers to the Northeast was Ralph Finch who visited the Koch kingdom during the reign of King Nara Narayan. The narrative was included in Richard Hakluyts The Principal Navigations and later published as Ralph Fitch, England's Pioneer to India and Burma: His Companions and Contemporaries, With His Remarkable Narrative Told in His Own Words in 1899. J Horton Ryley describes Fitchs travel to India as the first successful English expedition to discover the Indian trade. He makes the link between travel writing and em-

Madan Sarma travels through history to rediscover the world of travel writing in Assam

FRONTIS PIECE

G RRRRRRT

IN Assam, travel writing did not assume much significance till the end of the 1980s, when one noticed established creative writers and critics writing about travels

pire building and expansion of capitalism explicit. Fitch arrived at Kochbehar around 1586. He mentions Suckel Counse (presumably Sukladhwaj, brother of Nara Narayan, also known as Chilarai) as the king of the country. The kingdom, Fitch notes, had hospitals for sheep, goats, dogs, cats, birds and all other living creatures. Dutch traveller Frans van der Heiden (wrongly identified as Glanius by some historians) who accompanied the invading army of Mir Jumla in 1661 also wrote about his experiences in Assam. Niccolo Manuccis Storio do Mogor contains an account of Mir Jumlas campaign in Assam, though Manucci stayed back in Dhaka and gathered his information from soldiers who had returned from Gargaon. Shihabuddin Talishs Tarikh-i-mulk-ibriya includes an eyewitness account of Assam during 1662-1663. Two French travellers, Jean Baptiste Tavernier (Six Voyages, translated in 1677) and Francois Bernier, wrote about their experiences in Assam and recorded valuable information about the social and economic condition of the province in the mid17th century. Nearly a hundred years after Tavernier, a French agent, Jean Baptiste Chevalier, travelled to Assam. The Adventures of Jean Baptiste Chevalier in Eastern India (17521765) remained almost unknown till 2008, when Caroline Dutta Baruah and Jean Deloche published an English translation. The book contains an interesting account of Assam during the reign of Rajeswar Singha. The aim of Chevaliers travel was to establish commercial transaction between the French and the Ahom monarchy. Chevalier made many disparaging comments and observations about the people of the region. His experience shows that after Mir Jumlas invasion, foreigners found it very difficult to enter Assam. Chevaliers account shows how travel writers bias and gaze very often colour their factual narration. English soldiers and merchants started travelling to the region towards the end of the 18th century. Thomas Welsh who came to assist King Gaurinath Singha (179294) in his battle against the Moamarias furnished valuable information about the country in his report to the Governor General in 1794. John Peter Wade travelled in Assam and stayed here for one-and-a-half years since 1772 and wrote An Account of Assam. Francis Buchanan Hamilton visited Assam in

1807 and wrote An Account of Assam. William Griffiths Travels in Assam, Burma, Bhutan, Afghanistan and the Neighbouring Countries (1847) is not exactly a travel narrative. It, however, contains a wealth of information on indigenous plants and also shows the authors attempt to locate tea bushes in different places in upper Assam. The documentation undertaken by Griffith does not appear to be just an essential aspect of scientific exploration. It might be inspired by the interest of colonial commercial expansion. John Butlers Travels and Adventures in The Province of Assam (1855) with its focus on a truly adventurous journey and keen observation is an interesting narrative. Perhaps the first modern travelogue in Assamese was Jnanadabhiram Baruas Bilatar Cithi. It consists of a series of letters narrating his journey to and travels in United Kingdom. Barua tries to present an independent perspective to the events and milieu. Baruas letters were serialised in the Assamese monthly Banhi over a period of three years from 1909. Interestingly, Barua informs his readers about the sinking of the Titanic in 1912. Nearly two decades before that, Gunabhiram Barua wrote his travel narrative Saumar Bhraman in 1890 and Ananda Chandra Agarwala his Brahmajatrir Diary in 1895. The latter is a brief account of the authors travels in and around Rangoon. Both the narratives were published in the Assamese monthly Jonaki. Jnanananda Jagati narrates his adventurous journey to Manipur in Manipur Jatra, serialised in Banhi in 1911. One of the early travel writing of the 20th century is Rajanikanta Bordolois Puri

Bhraman (1914). Assamese travel writing came of age in the post-independence period. In the hands of a number of creative writers such as Birinchi Kumar Barua (Switzerland Bhraman, 1948; Professor Baruar Sithi, 1968) and Hem Barua (Xagor Dekhisa, 1954; Ronga Korobir Phul, 1959; Israel, 1965; Mekong Noi Dekhilo, 1967) travel writing became more creative, critically engaged and personalised. However, even before these texts, an important travel narrative was written by Purnakanta Burhagohain in 1943, though it had to wait for 50 years to see the light of day. Published posthumously, Purnakanta Burhagohains Patkair Xipare Na Basar (Nine Years beyond the Patkai) records the authors adventurous journey to Burma across the Patkai mountains and his travels in Burma, Thailand and parts of China between 1933 and 1942. His journey becomes, in part, a journey to the past both painful and glorious as he makes determined efforts to locate the Assamese villages in Burma and meet and interact with the descendants of the men and women taken away by the Burmese invaders of Assam in 1824. He also and visits the places inhabited by the ancestors of King Siukapha. In the Western world, travel writing came to be studied seriously from multiple perspectives in the 1970s. In Assam, travel writing did not assume much significance till the end of the 1980s, when one noticed established creative writers and critics writing about travels. Among them are: Navakanta Barua (Dexe Dexe Mor Dex, 1989), Medini Chaudhuri (Yangzu Nodir Par, 1987), Nirmalprabha Bordoloi (Bismoyakar Chin aru Cheryphular Dex Japan, 1991), Nirupama Borgohain (Romanchakar Rajasthan, 1998; Xarag Narakar Mazedi, 2003; Ei Dwip Ei Nirbaxan, 2003), Lakshminandan Bora (Paschimar Pom Khedi, 1991; Joralaga Germanit, 1993; Xeemar Paridhi Bhedi, 1997), Nagen Saikia (Mahachinar Dinlipi, 1994; Amerikat Dahdin, 1988), Govinda Prasad Sharma (Daffodil Phul Dekhisa, 2007), Karabi Deka Hazarika (Nila Sagar aru Xonali Dex), Pradipta Borgohain (Linconar Dexat Atithi, 1999) and Rohini Kumar Barua (Tritiya Biswar Tinikhan Dexat, 2006). Writers like Gautam Prasad Barua and Govinda Prasad Sharma adopted a fresh and critical outlook and interesting narrative strategies in their travel writings. These writers do not look at the Western world with any reverence, awe or sense of wonder. They are imaginative and critical and they look at themselves, at their society as they go on watching and savouring what they see and imbibe in distant lands. Today, it is perhaps time for our travel writers to take a fresh look at what is familiar or vaguely familiar. As Mary Louise Pratt reminds us, In the neoliberal order that consolidated itself in the 1990s, the stories are generated at the metropoliss own borders, sometimes right before its inhabitants eyes. T

Travels in Greeneland

P

sider'; in fact, he once says that he likes his life as an outsider resident in ICO Iyer is known to a small suburb of Japan most Indian readers with his Japanese wife Hifor Video Night in roko, precisely because Kathmandu, his latehe will always remain an eighties rollicking account outsider there, no matter of journeys through Asian how well he learns the cities, which accurately language and tries to fit and hilariously captured in. And finally there is the their spirit and mood. But interest in religion. Many over the years he has foof the themes in Greene's cused as much on his esbooks have underlying says and books on perreligious issues, and sonal and spiritual questions that can only themes, as on his travel be termed spiritual, writing. In The Man Withthough not always exin My Head he straddles plicitly recognised as both worlds, exploring the THE MAN WITHIN MY HEAD such, and these confront life and writings of his 'virand confound the protual father', the late nov- Pico Iyer tagonists of his novels. elist Graham Greene, Greene's position on this while weaving in ac- Penguin, 2012 was that in this world, counts of his own jour- `499, 241 pages avoiding sinful conduct neys to exotic locations Hardcover/ Non-fiction is not a central characacross the world. But teristic of holiness; comGreene always looms in the background, sometimes in Iyer's head, passion is far more important. As a lifelong devotee, Iyer's knowledge or in the form of one of his novels reread in about and empathy with Greene and the Bhutan or Bolivia. At times, Iyer also makes a tentative at- protagonists of his novels makes him a tempt to understand his own philosopher sure guide to Greeneland. He leads us father, Raghavan Iyer. Even in the passages through many memorable and ambiguous about his father, Greene puts in an ap- characters in Greene's novels the 'whisky pearance - the last words said to him by his priest' in The Power And The Glory, Major father were about an essay written by Iyer Scobie in The Heart of the Matter, and on Greene. But the fathers who create us Fowler, the journalist, in The Quiet Ameriare harder to forgive than the ones we cre- can, to name a few. Tortured souls, living ate, because they're much harder to es- in lands wracked by violence, poverty and cape. Unsurprisingly, then, after some hes- misery, they traverse an ambivalent moral itant approaches towards the figure of his universe, and yet find redemption in small real father, Iyer returns to the theme of Gra- acts of kindness. For Greene, religion did ham Greene, the literary father he has cre- not mean certainty of belief or truth, but he ated for himself and the title of whose first could never repudiate it entirely, recognisnovel, The Man Within, is reprised in the ing that in some of its simpler values lay hope for those who could not settle down title of this book. to conventional 'good'. And his characters shady, seedy, shiftless losers often operating on the wrong side of the law somehow manage to retain some moral fibre Graham Greene is undoubtedly one of the amidst lives of deceit and betrayal. While Iyer is unstinting in his praise of major figures of 20th-century English literature. He found popular acceptance as well Greene's novels, he is justifiably critical of as literary acclaim, and many of his novels his travel writings. As a travel writer, Greene were adapted into films, some many times took a jaundiced view of the places he visover. But he remained an elusive, contro- ited, most notably in The Lawless Roads, versial and contradictory figure, which prob- his travelogue on Mexico that preceded ably weighed against him at times as ev- The Power and the Glory, set in the same idenced by the fact he was never awarded land, and arguably his greatest novel. Dethe Nobel Prize, a tribute he richly deserved. scribing it as 'dyspeptic, loveless, savageUnable to settle in one place for very long ly self-enclosed and blind', Iyer points out or into long-term relationships, he was the that hate is the predominant note in this perpetual outsider, forever journeying to book. Fortunately for us, as a travel writer, exotic and dangerous locations. He often Iyer is the complete opposite, and the bits contemplated suicide, including an attempt of travel notes strewn through this book in childhood when he played Russian are a delight. Even in the most difficult and roulette six times over, until he decided that trying of situations. For example, in Sri he had tempted fate enough. Greene poured Lanka at a time when the conflict between much of himself into his novels, and his the LTTE and the government was at its protagonists were similarly conflicted peak, he usually finds much that is posipersonalities, treading uncertain moral tive in both the land and the people. He ground, both politically and personally, writes about his meeting with Lasantha a territory of the soul that came to be Wickramatunge, editor of The Sunday Leader, who expected to be killed for his dubbed Greeneland. Though separated in time by two gener- journalistic work by agents of the governations, there are many obvious similarities ment a prediction that came true two between Greene and Iyer, and it is easy to years later. This book is an absolute must not only see just why Greene preoccupies Iyer, to the extent of obsession. Both were educat- for Graham Greene buffs, but even for ed in England, under a system that pro- those who have read a Greene novel or duced those who governed empire as well two and liked it. But if one does not have as notable failures who became derelicts in at least a nodding acquaintance with the far-flung colonies of that empire. Greene Greene, it is likely to be trying and tewas perpetually on the move, and would dious. The parts about travel are excelturn up in the most unexpected places. This lent, but those about his father do not reis a fascination that Iyer clearly shares, hav- ally come to life. Iyer's meditations and ing led a peripatetic existence since his child- thoughts on various subjects are inhood between boarding school in England sightful, but they depend always on refand vacations at his home in California, erencing Greene and his works. Unlike leading to a lifetime of travel and writing Video Night in Kathmandu, this is not a book for every reader but for the Greene luminously about the experience. Iyer shares Greene's self-image as an out- fans among us. T

VIDYADHAR GADGIL

CLOSE READING

Sights, sounds, smells of Europe

PRADIPTA BORGOHAIN

OBINDA Prasad Sarma is a well-known figure in the literary landscape of Assam. He has authored several works of fiction and non-fiction, including literary criticism, biography, travelogue, and collections of short stories. Lailac Phul Phulibor Botor (Time for Lilacs to Bloom) is his second travel narrative. The first, Daffodil Phul Dekhisa (Have You Seen Daffodil Flowers, 2007), had managed to attract the approbation of critics as well as the admiration of general readers. This work, revolving around a conducted tour the writer undertook in continental Europe and the United Kingdom accompanied by his wife Anjali Sarma, is likely to at least equal, if not exceed, the success of its precursor. The work is a testimony to the storytelling skills of the writer. This is important because objective or factual descriptions of places and peoples are not likely to rivet the attention of the readers any longer in the era of globalisation. The aura of unfamiliarity attached to far places has vanished as distances have shrunk with the improvement of transport and communication. If anything, the challenge for a

writer now is probably to restore the magic and allure of places other than ones homelands. However, the book has something for everybody. The reader looking for information and valuable tips for travel in Europe will not be disappointed by Lailac Phul Phulibor Botor. If anything, there is almost a surfeit of information about travel strategies, finance options, and the hospitality indexes of different places. But to the credit of Sarma, he makes the abundant details come alive with touches of creativity. The work has a strong component of what we might choose to call the raconteurs relish. The journey that he undertook with his wife in Europe is replete with instances of this relish. Sarma evidently enjoyed travelling and then writing about his travels, and he communicates this enjoyment to the reader. After reading the book one feels the urge not only to pack up all the travel bags and gear but also to make a resolve to hoard all the details of the forthcoming journey in the storehouse of the mind so that one can come back and write about the fascinating sights and sounds and smells of the new place. This is then a book not only for the potential traveller but also for the potential travel writer. A meticulous and methodical

CLOSE READING

RRRRRRT G

SARMA is a romantic at heart who embarks on a quest for the Holy Grail which in this case happens to be the lilac flower...

over misplaced bags, cards not accepted by ATMs, and possibilities of missing flights or trains seem to have given the couple a harrowing time. Such events, while causing distress to the travellers, impart a certain flavour to the work, making it more rollicking and readable than it might otherwise have been. The two things that distinguish Sarma the traveller and the travel writer are: one, that he is a very erudite person intent on adding to his treasury of existing knowledge, and two, that he is a romantic at heart who embarks on a quest for the Holy Grail which in this case happens to be the lilac

LILAC PHUL PHULIBOR BOTOR

Gobinda Prasad Sarma Banalata, 2011 `120, 296 pages Hardcover/Travel

traveller, Sarma yet finds that things sometimes have a way of going haywire and give him moments of anxiety. These anxieties

flower. Sarma has read about the lilac flower in the poetry of TS Eliot as a student of literature, and ever since then has felt the urge to go looking for it in the land of its origins. This quest itself is a fascinating story and in telling it the author draws the readers along with him, making them wonder how and where the flower would finally be tracked down. There is another initiatory desire, that of the cultural traveller who feels the attraction of the great,

ancient sites of human civilisation: From my childhood I had an intense desire to see the Europe where this civilisation [Greek civilisation] prevailed, its light providing humankind with a wisdom-based philosophy and a direction for art and culture. As the writer sees the cradles of civilisation in Europe that he has longed to see all his life, he also gives the reader a kind of conducted tour through these places because he has so much to tell them about the myths and legends associated with these places. For example, on reaching the Acropolis and the Parthenon, he tells us about the goddess Athena, the patronsaint of old Greece. Similarly, while visiting Rome, we get to hear about Remus and Romulus, the legendary founders of Rome, as well as the tyrannical and eccentric emperor Nero, who famously fiddled while all around him Rome burnt. The writer also has many illuminating things to say about intellectual and literary figures of Europe such Rousseau, Voltaire, Walter Scott, and the Bronte sisters. As a result

of all this the readers are not only enlightened but their curiosity to visit the birthplaces and workplaces of these famous personalities is whetted. The work on the whole is extremely enjoyable. Its not only saturated with valuable information, but is crowded with interesting incidents and colourful characters. The reader is made to realise that the places one visits are not empty places of splendour and spectacle, but that they are inhabited by people who are very like us in some ways but also differ in some crucial ways. The reader feels at the end of it that he would like to know people such as Manohar Jogi and Shilpi and Girish Aggarwal and count them among his friends. At times the writer pauses in his admiring descriptions of the distant places to let his mind flit back to the many shortcomings and deprivations of his homeland. Why cant our own state attain even the modicum of the efficiency, cleanliness and hospitality that make the various countries of Europe such shining destinations for the eager traveller? Gobinda Prasad Sarmas book is a very enticing introduction to the cultural, geographical and social map of Europe. With his erudition, self-deprecating humour, acute powers of observation, and sensitivity to the beauty of nature, he succeeds in recreating his journey in a way that makes a lasting impact on the readers mind. T

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an EmpireD'EverandThe Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an EmpireÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (145)

- Keller SME 12e PPT CH01Document19 pagesKeller SME 12e PPT CH01NAM SƠN VÕ TRẦN100% (1)

- Paint Industry: Industry Origin and GrowthDocument50 pagesPaint Industry: Industry Origin and GrowthKarishma Saxena100% (1)

- Sindh Province of PakistanDocument11 pagesSindh Province of PakistanAyesha NoorPas encore d'évaluation

- Actually Profiling Mughal Empire: What Did Bernier TheDocument26 pagesActually Profiling Mughal Empire: What Did Bernier The5129 DheerendraPas encore d'évaluation

- Colonialism and Travel LiteratureDocument5 pagesColonialism and Travel LiteratureJaveed GanaiePas encore d'évaluation

- Travelers WritersDocument6 pagesTravelers WritersMadalina Elena PopescuPas encore d'évaluation

- Types of Literature: LITETRATURE (1900 TO 1930)Document9 pagesTypes of Literature: LITETRATURE (1900 TO 1930)SHEFALI KULKARNIPas encore d'évaluation

- An Illustrated History of Indian Literature in English - Arvind Krishna Mehrotra - Anna's ArchiveDocument483 pagesAn Illustrated History of Indian Literature in English - Arvind Krishna Mehrotra - Anna's ArchivedillipinactionPas encore d'évaluation

- Development of Indian English Prose by Akshay NarayanDocument4 pagesDevelopment of Indian English Prose by Akshay Narayanakshay100% (2)

- Traveller Year of Visit To India Nationality Name of The Book Traveller's Occupation and RemarksDocument9 pagesTraveller Year of Visit To India Nationality Name of The Book Traveller's Occupation and RemarksAmaresh JhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Travel Literature: A Perspective On The History of Indian Travel Accounts and Recent Developments in The GenreDocument4 pagesTravel Literature: A Perspective On The History of Indian Travel Accounts and Recent Developments in The GenreIJELS Research JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Afro Asian LiteratureDocument9 pagesAfro Asian LiteratureJon Michael BoboyoPas encore d'évaluation

- Travel Iran 17thcent PDFDocument37 pagesTravel Iran 17thcent PDFAmir MjPas encore d'évaluation

- TravelersDocument9 pagesTravelersAjay singhPas encore d'évaluation

- Travel Writing - A Critical Study of William Dalrymple's "In Xanadu A Quest"Document22 pagesTravel Writing - A Critical Study of William Dalrymple's "In Xanadu A Quest"EnzoPas encore d'évaluation

- Jalijangal in The Form of English Translation As The Forest Goddess by Badri Nath Bose. TheDocument79 pagesJalijangal in The Form of English Translation As The Forest Goddess by Badri Nath Bose. ThePushpanathan ThiruPas encore d'évaluation

- Early Modern Literature (19th Century)Document10 pagesEarly Modern Literature (19th Century)Masyita Rizkia RachmaPas encore d'évaluation

- 06 - Chapter 1 - 2Document57 pages06 - Chapter 1 - 2RaviLahanePas encore d'évaluation

- House For MR Biswas Notes PDFDocument59 pagesHouse For MR Biswas Notes PDFangdrueay100% (15)

- Indian English Fiction After 1980Document47 pagesIndian English Fiction After 1980Surajit MondalPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 1 CompleteDocument13 pagesModule 1 CompleteJira Finella AntonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Omat. Hum-Indian Writing in English in The Wake ofDocument8 pagesOmat. Hum-Indian Writing in English in The Wake ofImpact JournalsPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit About The Short Story: StructureDocument12 pagesUnit About The Short Story: StructureMEG MENTORS IGNOU MA ENGLISHPas encore d'évaluation

- Wonders of the Himalaya: Explorations in Central Asia, Karakorum and PamirD'EverandWonders of the Himalaya: Explorations in Central Asia, Karakorum and PamirPas encore d'évaluation

- The Long Journey: Exploring Travel and Travel WritingD'EverandThe Long Journey: Exploring Travel and Travel WritingMaria Pia Di BellaPas encore d'évaluation

- History From Below. What Shaped The Thought of Thompson (Nota de Satia en Aeon)Document7 pagesHistory From Below. What Shaped The Thought of Thompson (Nota de Satia en Aeon)Juan Martín DuanaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Travels of an Alchemist - The Journey of the Taoist Ch'ang-Ch'un from China to the Hindukush at the Summons of Chingiz KhanD'EverandThe Travels of an Alchemist - The Journey of the Taoist Ch'ang-Ch'un from China to the Hindukush at the Summons of Chingiz KhanÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Tej Singh Becomes Friday's ChildDocument45 pagesTej Singh Becomes Friday's ChildSandeep Badoni100% (1)

- Nadine Gordimer-South African WritterDocument11 pagesNadine Gordimer-South African WritterAj Claire IsagaPas encore d'évaluation

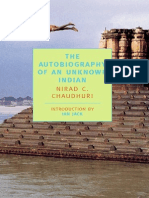

- Autobiography Unknown Indian IntroductionDocument11 pagesAutobiography Unknown Indian IntroductionTruely Male100% (2)

- HillDocument15 pagesHillB.RandPas encore d'évaluation

- Rabindranath Tagore and Mulk Raj AnandDocument4 pagesRabindranath Tagore and Mulk Raj AnandNiban Ilawur0% (1)

- Important Foreign TravellersDocument2 pagesImportant Foreign TravellersHabib ManzerPas encore d'évaluation

- Sair-E Europe and Safarnama-E Rum-o-Misr-o ShaamDocument11 pagesSair-E Europe and Safarnama-E Rum-o-Misr-o ShaamSumaira Nawaz100% (1)

- 06 - Chapter1 Jhmpa IntroductionDocument39 pages06 - Chapter1 Jhmpa IntroductionKavita AgnihotriPas encore d'évaluation

- Kitne Pakistan 2Document6 pagesKitne Pakistan 2api-3845064100% (1)

- Histroy Class 12 Theme 2Document146 pagesHistroy Class 12 Theme 2guru1241987babuPas encore d'évaluation

- History12 - 1 - Foreign Travellers To India PDFDocument25 pagesHistory12 - 1 - Foreign Travellers To India PDFRavi GarcharPas encore d'évaluation

- 06 Chep1 PDFDocument19 pages06 Chep1 PDFyogaPas encore d'évaluation

- Block 4Document47 pagesBlock 4PRINCESS AULEEN M. SAN AGUSTINPas encore d'évaluation

- Books in My LifeDocument47 pagesBooks in My LifedakilokicaPas encore d'évaluation

- Themes in Indian History (English) Part - 1Document10 pagesThemes in Indian History (English) Part - 1Diwas VermaPas encore d'évaluation

- Jess308 PDFDocument12 pagesJess308 PDFRajat SabharwalPas encore d'évaluation

- Poetry of The Masses and Early National PeriodDocument7 pagesPoetry of The Masses and Early National PeriodMark Jade CosmodPas encore d'évaluation

- CH 5 To 8Document109 pagesCH 5 To 8Rohit RockyPas encore d'évaluation

- Detail of Foreign Travelers - MygkjunctionDocument6 pagesDetail of Foreign Travelers - MygkjunctionGopal PrasadPas encore d'évaluation

- 21st ReviewerDocument10 pages21st ReviewerEndeavorMakioPas encore d'évaluation

- Asian-And-North-Amerika 20231130 185740 0000Document59 pagesAsian-And-North-Amerika 20231130 185740 0000Mark Stephen DamgoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Last Mughal: The Fall of A Dynasty: Delhi, 1857Document15 pagesThe Last Mughal: The Fall of A Dynasty: Delhi, 1857Georgie0% (1)

- Highway Through Governance Hell: ScriptDocument1 pageHighway Through Governance Hell: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Japanese LiteratureDocument13 pagesJapanese LiteraturePepe CuestaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter - Iii History of Tourism and Hospitality Industry and Agro TourismDocument28 pagesChapter - Iii History of Tourism and Hospitality Industry and Agro Tourismkhalsa computersPas encore d'évaluation

- History of American LiteratureDocument3 pagesHistory of American LiteratureAyeshaPas encore d'évaluation

- Shifting Themes & Thoughts: Indian English Novel WritingDocument9 pagesShifting Themes & Thoughts: Indian English Novel WritingatalkPas encore d'évaluation

- 05 Chapter1Document34 pages05 Chapter1Muhammed AsifPas encore d'évaluation

- 06 Chapter 1Document20 pages06 Chapter 1Mayank RawatPas encore d'évaluation

- Famous Travelers in Africa: TH TH THDocument9 pagesFamous Travelers in Africa: TH TH THAni JariashviliPas encore d'évaluation

- Prakashan: Novels, Society and HistoryDocument33 pagesPrakashan: Novels, Society and HistoryRohan VishwakarmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Post Colonial Literature With Reference To Salman RushdieDocument4 pagesPost Colonial Literature With Reference To Salman RushdieLaxmi Jaya100% (1)

- Festivals of Northeast: Mizoram: ScriptDocument1 pageFestivals of Northeast: Mizoram: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Enduring Marriage: ScriptDocument1 pageEnduring Marriage: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Building A Reading Culture: ScriptDocument1 pageBuilding A Reading Culture: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Festivals of Northeast: Mizoram: ScriptDocument1 pageFestivals of Northeast: Mizoram: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Jul 15, 2012 P3Document1 pageJul 15, 2012 P3NElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- The Race: ScriptDocument1 pageThe Race: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- The Making of A Champion: ScriptDocument1 pageThe Making of A Champion: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Let The Imagination Fly: ScriptDocument1 pageLet The Imagination Fly: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Journey To Bhiwani Junction: ScriptDocument1 pageJourney To Bhiwani Junction: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Jul 29, 2012 p2Document1 pageJul 29, 2012 p2NElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Aug 05, 2012 P3Document1 pageAug 05, 2012 P3NElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Jul 15, 2012 P2Document1 pageJul 15, 2012 P2NElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Refugees, Idps and The Stateless: Forced Migration in NeDocument1 pageRefugees, Idps and The Stateless: Forced Migration in NeNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Jul 29, 2012 p2Document1 pageJul 29, 2012 p2NElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Enduring Marriage: ScriptDocument1 pageEnduring Marriage: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Jul 22, 2012 P2Document1 pageJul 22, 2012 P2NElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- A Post-Prayer Poem: Hiruda and His Musical JourneyDocument1 pageA Post-Prayer Poem: Hiruda and His Musical JourneyNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Enduring Marriage: ScriptDocument1 pageEnduring Marriage: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Appropriating Rabha: Outcast To Icon: ScriptDocument1 pageAppropriating Rabha: Outcast To Icon: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Pherengadao: Breaking Dawn: ScriptDocument1 pagePherengadao: Breaking Dawn: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Fragrant Butterflies: ScriptDocument1 pageFragrant Butterflies: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- A Tale of Thirdness: ScriptDocument1 pageA Tale of Thirdness: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Fragrant Butterflies: ScriptDocument1 pageFragrant Butterflies: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Jun 17, 2012 P3Document1 pageJun 17, 2012 P3NElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Jun 10, 2012 P2Document1 pageJun 10, 2012 P2NElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Jun 17, 2012 P2Document1 pageJun 17, 2012 P2NElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Jun 10, 2012 P3Document1 pageJun 10, 2012 P3NElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature From Arunachal: Old Voices and NewDocument1 pageLiterature From Arunachal: Old Voices and NewNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- A Dirge From The Northeast: ScriptDocument1 pageA Dirge From The Northeast: ScriptNElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- May 27, 2012 P3Document1 pageMay 27, 2012 P3NElitreviewPas encore d'évaluation

- MDSAP AU P0002.005 Audit ApproachDocument215 pagesMDSAP AU P0002.005 Audit ApproachKiều PhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Collaborative Family School RelationshipsDocument56 pagesCollaborative Family School RelationshipsRaquel Sumay GuillánPas encore d'évaluation

- Crla 4 Difficult SitDocument2 pagesCrla 4 Difficult Sitapi-242596953Pas encore d'évaluation

- Single Entry System Practice ManualDocument56 pagesSingle Entry System Practice ManualNimesh GoyalPas encore d'évaluation

- PROJECT CYCLE STAGES AND MODELSDocument41 pagesPROJECT CYCLE STAGES AND MODELSBishar MustafePas encore d'évaluation

- Palarong Pambansa: (Billiard Sports)Document10 pagesPalarong Pambansa: (Billiard Sports)Dustin Andrew Bana ApiagPas encore d'évaluation

- John 4 CommentaryDocument5 pagesJohn 4 Commentarywillisd2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sd-Wan Zero-to-Hero: Net Expert SolutionsDocument11 pagesSd-Wan Zero-to-Hero: Net Expert SolutionsFlorick Le MahamatPas encore d'évaluation

- Cracking Sales Management Code Client Case Study 72 82 PDFDocument3 pagesCracking Sales Management Code Client Case Study 72 82 PDFSangamesh UmasankarPas encore d'évaluation

- Planning Theory PPT (Impediments To Public Participation)Document16 pagesPlanning Theory PPT (Impediments To Public Participation)Sanjay KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Module in Mapeh 7: Directions: Do You Have A Diary? Where You Able To Make One? Write in Your DiaryDocument4 pagesModule in Mapeh 7: Directions: Do You Have A Diary? Where You Able To Make One? Write in Your DiaryChristian Gonzales LaronPas encore d'évaluation

- Sapexercisegbi FiDocument18 pagesSapexercisegbi FiWaqar Haider AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Oral Medicine Lecture NotesDocument3 pagesClinical Oral Medicine Lecture NotesDrMurali G ManoharanPas encore d'évaluation

- Bank Secrecy Law ExceptionsDocument5 pagesBank Secrecy Law Exceptionsjb_uy100% (1)

- ASEANDocument2 pagesASEANJay MenonPas encore d'évaluation

- Common University Entrance Test - WikipediaDocument17 pagesCommon University Entrance Test - WikipediaAmitesh Tejaswi (B.A. LLB 16)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Discourses and Disserertations On Atonement and SacrificeDocument556 pagesDiscourses and Disserertations On Atonement and SacrificekysnarosPas encore d'évaluation

- Adr Assignment 2021 DRAFTDocument6 pagesAdr Assignment 2021 DRAFTShailendraPas encore d'évaluation

- The Classical PeriodDocument49 pagesThe Classical PeriodNallini NarayananPas encore d'évaluation

- North Carolina Wing - Jul 2011Document22 pagesNorth Carolina Wing - Jul 2011CAP History LibraryPas encore d'évaluation

- The Humanization of Dogs - Why I Hate DogsDocument1 pageThe Humanization of Dogs - Why I Hate Dogsagentjamesbond007Pas encore d'évaluation

- ChinnamastaDocument184 pagesChinnamastaIoan Boca93% (15)

- Exam Kit Extra Practice Questions (Suggested Answers)Document3 pagesExam Kit Extra Practice Questions (Suggested Answers)WasangLi100% (2)

- John Snow's pioneering epidemiology links Broad Street pump to cholera outbreakDocument4 pagesJohn Snow's pioneering epidemiology links Broad Street pump to cholera outbreakAngellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Been Gone PDFDocument2 pagesBeen Gone PDFmorriganssPas encore d'évaluation

- Pointers-Criminal Jurisprudence/gemini Criminology Review and Training Center Subjects: Book 1, Book 2, Criminal Evidence and Criminal ProcedureDocument10 pagesPointers-Criminal Jurisprudence/gemini Criminology Review and Training Center Subjects: Book 1, Book 2, Criminal Evidence and Criminal ProcedureDivina Dugao100% (1)

- Engineering Forum 2023Document19 pagesEngineering Forum 2023Kgosi MorapediPas encore d'évaluation

- Grill Lunch MenuDocument2 pagesGrill Lunch Menuapi-230748243Pas encore d'évaluation