Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Yi

Transféré par

woodman0103Description originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Yi

Transféré par

woodman0103Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

MCMAP and the Marine Warrior Ethos

Captain Jamison Yi, U.S. Marine Corps

URING THE 1970s, after the Vietnam War, legitimate and necessary instruments of violence una self-identity malaise befell the U.S. Armed der authorized state control, adopting recruiting stratForces. Pacifism, self-indulgence, and egalitarian egies that avoided appeals to the warrior spirit, pamulticulturalism supplanted selfless patriotism as triotism, or the obligations of citizenship. They emphasized personal core values across the self-advancement and spectrum of American promotion. As a result, social institutions. Key Water the public did not see segments of society Survival the military as a noble publicly expressed coninstitution standing tempt for any notion of guard over the Nation, service as an obligation but as the employer of of citizenship, including last resort for mempatriotic service in the bers of society who military. This view behad no other options came commonplace for employmenta throughout the Nations public-works program educational system, for Americas least-talreligious organizations, ented citizens. institutions of higher The adverse influlearning, and among inCHARACTER ence of these views fluential members of DISCIPLINE rippled through the society, including politimilitary. Military traincal figures, members of ing regimens came to the media, and enterreflect the wateredtainment-industry lumiSynergy of Disciplines down values of society. naries. In the then-prevailing environment, the military and the warrior Physical training standards were lowered, dress ethos it represented were publicly ridiculed and standards were relaxed, and disciplinary problems, blamed. Marxist revisionist historians, then dominat- including rampant drug abuse, were virtually tolering the Nations campuses, laid the worlds social ated. The tendency of dominant political leaders to and economic inequalities and injustices at the view military intervention as pass exacerbated the Pentagons door. Because of the unpopularity of military service problem. The military was seen more as an instruand the dominant influence 1960s counterculture at- ment of social engineering than an instrument of natitudes had on U.S. social and political agendas, the tional power that should be kept finely maintained military shied from publicly identifying themselves as and honed. 17

MILITARY REVIEW

November - December 2004

Marines demonstrate MCMAP take-down techniques. (Inset) A Marine executes the technique during operations near the Diyala Canal Bridge leading into Baghdad.

The 1970s were onerous and bitter for the American Samuraithe career men and women in uniform who viewed their service in the military and devotion to country as a calling, not just an occupation. Among them were those who had fought with valor in Vietnam and other conflicts and who, with bitterness and resentment, saw the dry rot of the me generations shallow hedonism eating away at society and their services bedrock values. The predictable consequence was that such individual values translated into a failure to maintain military readiness and, ultimately, the failure to accomplish military missions on the field of battle.

Operation Eagle Claw

Operation Eagle Claw, the infamous Desert One Iranian Hostage rescue attempt that occurred in 1979, was a disaster. The operation involved an ad hoc force of brave, well-intentioned but illequipped and ill-trained personnel from the U.S. Navy, Air Force, Army Special Forces, and the Marine Corps. In congressional testimony, Chief of Staff of the Army General Edward Shy C. Meyer declared he was presiding over a hollow Army. Congressional leaders were shocked into recognizing that the military had fallen into a state where it was no longer capable of performing many of its basic missions. 18

Under the new administrations leadership, congressional and military leaders began restoring the Nations military capabilities by appointing unvarnished warriors, notably short on political correctness, to positions of high authority. In 1980, General Alfred M. Gray became the new USMC commandant. His appointment signaled a renaissance of the warrior ethic throughout the services. Gray, a warriors warrior, began immediately to revitalize the USMC warrior ethic by reintroducing bayonet training as part of the basic package for all Marine recruits, supplementing this training with physically demanding martial skills that simulated one-on-one combat. The purpose of this bruising, demanding training was to reemphasize the importance of physical and competitive aggressiveness as a core element of the warrior ethos. Gray also introduced measures aimed at molding the USMCs intellectual and spiritual dimension. He established a required-reading program on subjects related to the art of warfare, challenging Marines to think deeply and broadly about the future environment in which they would have to ply martial skills. He directed the reprinting and distribution of the USMCs 1940 Small Wars manual that dealt with insurgencies of the type Gray believed would be the most likely kind of conflicts Marines

November - December 2004 MILITARY REVIEW

USMC

MARTIAL ARTS PROGRAM

Close quarters combat training.

USMC

would face in the future.1 In addition, he established the USMC School of Advanced Warfare and began the accreditation process for the USMC Command and General Staff College and the USMC War College. Subsequent commandants continued to build and expand warrior-ethos initiatives and innovations, and in 1991, General Carl E. Mundy, Jr., took what Gray achieved one step further by framing the USMC core values as honor, courage, and commitment, which have become the bedrock of a Marines character. In 1999, building on the foundation Gray and Mundy laid, Commandant General James L. Jones introduced the Marine Corps Martial Arts Program (MCMAP), modeled in part after martial arts systems that form the core physical training component of many East Asian armed services. The vision for the program originated during Joness tour of duty as a lieutenant in Vietnam where he served alongside Republic of Korea (ROK) Marines and observed with keen interest how challenging physical combative training and a national military martial arts system unified these extremely skilled and fearsome Marines around a shared warrior ethos. Friend and foe alike knew ROK Marines were individually trained masters of close quarters combatblack belts in Tae Kwon Doable to deal personally and ruthlessly with any enemy. To highlight their mystique and reputation, ROK Marines wore a unique uniform (tiger-striped fatigues) distin-

guishing them from other soldiers. Jones observed that the ROK Marines reputation so intimidated Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army units they actively avoided ROK forces during combat. This insight profoundly affected Jones and shaped his vision of the course the USMC should follow. He concluded that instituting a training program to instill the same closequarters combat warrior ethos the USMC had when it was first organized was again essential if it was to fully prepare to fight the intensely personal, low-intensity, expeditionary, small wars that military strategists were predicting would dominate the 21st century.

The Marital Arts Program

Since its introduction, MCMAP has been tested, evaluated, and refined. It combines the best combat-tested martial arts skills and time-honored, closecombat training techniques with proven USMC core values and leadership training. MCMAP has its roots in the USMCs formative days when continental Marines were renowned for their skills as sharpshooters operating from the rigging of Navy ships when the tools of the trade of boarding and landing parties were the sword and bayonet. Early on, the Marines martial culture and warrior spirit were what made them effective, not their weapons. During World War I, the USMC trained Marines to be expert riflemen first and foremost. The motto

MILITARY REVIEW

November - December 2004

19

Tan Belt

Gray Belt

Green Belt

Green Belt

(Instructor-Qualified)

Brown Belt

Brown Belt

(Instructor-Qualified)

Black Belt

Black Belt

(Instructor-Qualified)

Black Belt

(Instructor-Trainer Qualified)

battlefieldsa martial-arts lifestyle created by Marines for Marines. Today, MCMAPs overarching purpose is to mold and strengthen the USMC collective identity, social structure, and culture. It is a martial-arts system that mandates intensive practice with weapons and unarmed techniques, intense physical conditioning, and the use of established milestone standards. In addition to physical conditioning, practical fighting skills, and the confidence such training instills, the system recognizes that brute force applied without a specific purpose is usually counterproductive. Consequently, MCMAP also stresses developing analytical discrimination to judge the appropriate use of force as a situation might dictate, even at the lowest tactical levels. MCMAP continually challenges Marines physically and mentally while testing and building ethical and moral character by compelling decisionmaking under stressful and punishing circumstances while choosing situation-appropriate force options. As a result, MCMAP engrains a bias for taking the initiative before the enemy does and shaping the battlefield by actions that create opportunities to exploit an enemys critical vulnerabilities. The program builds the physical and mental capabilities of the USMCs strategic corporals so in the absence of guidance from higher authority they can better fight the decentralized battle that maneuver-warfare doctrine envisions.

MCMAP Components

MCMAP consists of a belt-ranking system with five basic levelstan, gray, green, brown, and blackthat designate user levels. The belts are worn under the camouflage utility uniform. The individual Marine pursues each level for his own edification and to become a stronger link in the USMC chain. The users responsibilities include participating in all technique classes, tie-ins, warrior studies, sustaining techniques, and he must participate in the appropriate belt-level drills and freesparring. There are two instructional levels, each with clearly delineated responsibilities. Instructors belts have a 1/2-inch tan stripe on the buckle side of the belt. Instructor-trainers belts have a series of 1/2inch red stripes on the buckle side of the belt. MCMAP has three formal components: physical discipline, mental discipline, and character discipline. Each is divided into blocks and presented system-

Continuum of Force Taught During MCMAP Syllabus

1. Compliant (cooperative): Verbal commands. 2. Resistant (passive): Contact controls. 3. Resistant (active): Compliance techniques.* 4. Assaultive (bodily harm): Defensive tactics.* 5. Assaultive (serious bodily harm/death): Deadly force.* * Martial arts techniques.

was, Every Marine an Infantryman. Jones wanted to take the training further, however. He would train all Marines to be one-on-one warriorsmasters of modern high-tech combat environments as well as masters of low-tech, hand-to-hand, close-quarters combat. His vision was to take from the best Marine traditions and borrow from the best of other successful martial traditions to create an updated martial-arts system appropriate for current and future

20

November - December 2004

MILITARY REVIEW

MARTIAL ARTS PROGRAM

USMC

Testing the Marine Corps warrior spirit.

atically to Marines at each belt level. Many skills specific to one discipline reinforce the strengths of other disciplines, creating a synergistic program with mutually supporting dimensions. In content, MCMAP is predominantly a weapons-based system focusing on rifle and bayonet, edged weapons, weapons of opportunity, and unarmed combat across the entire spectrum of combat. Physical discipline. Physical discipline consists of armed and unarmed combat techniques combined as part of the USMC Physical Fitness Program and is the sinew of what every Marine must be prepared to executeto seek out, close with, and destroy the enemy by fire and movement or repel his assault by fire and close combat. Training, which is oriented on the battlefield and based on combat equipment, develops a Marines ability to make correct decisions while overcoming physical hardship and obstacles under any climatic condition. The unarmed combat system is a carefully developed aggregation of selected skills from more than a dozen disciplines of fighting. These armed and unarmed techniques have been systematically designed to enable Marines to fight in diverse situations and environments across the full spectrum of conflict, from high-intensity, force-on-force maneuver warfare to stability and support duties.

MILITARY REVIEW November - December 2004

The program teaches lethal and nonlethal techniques as well as pain-inducing compliance techniques to provide maximum flexibility for adapting to any possible threat level. Marines are taught methodologies for rapidly selecting and using appropriate techniques to fit the situation. Applying the right technique with the least required force to prevent situations from escalating beyond control is especially important in military operations other than war. Selecting justifiable techniques is also important. Two elements of the physical program support and complement each other: combative arts and combative conditioning. The combative arts are an aggregation of skills that become the essence of what every Marine, regardless of military occupational specialty (MOS), must be prepared to execute in seeking out, closing with, and destroying the enemy by fire and movement and repelling his assault by fire and close combat. Combative conditioning integrates combative armed and unarmed techniques with traditional physical-fitness training, water-survival training, and rough-terrain skills training. Combative conditioning is designed to mitigate human factors having physically debilitating effects on the human body during combat. Conditioning 21

MCMAP Belt-Ranking System

MASTER-AT-ARMS MCMAP consists of a belt-ranking system with five basic levels UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS tan, gray, green, brown, and black identified as user levels. They are 6th pursued for an individual Marines edification. By pursuing them the 5th Black user becomes a stronger link in the 4th Black Marine Corps chain. The users responsibilities include participating 3d Black in all technique classes, tie-ins, warrior studies, and sustaining 2d Black Advanced Skills and MAIT Qualified techniques. The user must also participate in the appropriate belt-level 1st Black Advanced Fundamentals drills and free-sparring. Brown Intermediate Fundamentals and Intro Tan Belt. Conducted at entryto Advanced Fundamentals of each Discipline level training as part of the tranGreen Intermediate Fundamentals of each Discipline sformation process, it requires 80 percent proficiency in basic techGray Basic Fundamentals and Introduction to Intermediate Fundamentals of each Discipline niques and basic understanding of USMC leadership and core value Tan Basic Fundamentals of each Discipline concepts. Weapons of Gray Belt. This follow-on trainRifle & Bayonet Edged Weapons Unarmed Combat Opportunity ing after entry level, which builds PHYSICAL DISCIPLINE on the basics with introduction to intermediate techniques, requires 90 percent mastery of tan-belt techniques and 80 martial arts. Advanced level skills training begins percent proficiency of gray-belt techniques along in earnest, and the user must demonstrate 90 perwith continued mental and character discipline traincent mastery of tan-, gray-, green-, and browning. Gray-belt training qualifies the user to attend belt techniques and 80 percent proficiency in the instructor course and qualify for MOS 8551. black-belt techniques. The user must be a proven Green Belt. For the noncommissioned officer, leader and mentor. Black-belt proficiency will green-belt training continues development of interqualify the user to attend the instructor trainer mediate-level training and requires 90 percent course and for MOS 8552. The user must become an mastery of tan- and gray-belt techniques and 80 instructor-trainer to progress any further within percent proficiency of green-belt techniques as the system. well as leadership and core-values development Black Belt (2d-6th degree). The user will contraining and PME requirements. Green-belt traintinue to develop and master all components of the ing qualifies the user to attend the instructor various disciplines and be a proven leader, teacher, trainer course and for MOS 8552. and mentor. This program is currently under develBrown Belt. At the brown-belt level, the user opment at the Martial Arts Center of Excellence at continues intermediate-level training and is introThe Basic School, Quantico, Virginia. duced to advanced techniques. To qualify, the Testing. Advancement in the belt-ranking sysuser must demonstrate 90 percent mastery of tan-, tem includes meeting mental and character discipline gray-, and green-belt techniques and 80 percent requirements and the prerequisites for each belt proficiency of brown-belt techniques and must be level. In addition each Marine must show he has able to teach leadership and core-values training. maintained proficiency in the physical disciplines of Black Belt (1st degree). To qualify as a black his current belt as well as the physical disciplines of belt, the user must become a serious student of the all previous belts.

e E trin IN g Doc IPL htin SC rfig DI d Wa AL ls an NT Skil ME mon m Co E, PM

22

Ma HA rin RA eC C orp T E sV R alu D es IS an CI dL P ea LIN de rsh E ip

November - December 2004

MILITARY REVIEW

allows Marines to fight in any terrain, under any climatic condition, and face the rigors of the dispersed battlefield. Combined, combative arts and conditioning develop a physical toughness expected to translate into mental toughness, producing Marines who possess combat fitness and combative skills to handle any situation they confront. Mental discipline. To cultivate this quality, MCMAP trains for certainty but educates for the unknown. To develop mental discipline and rigor, along with physical-skills training and conditioning, MCMAP mandates and measures the continuous study of the art of war, which includes professional military education (PME) and the professional reading program; Marine Corps Common Skills Training (MBST); decisionmaking training; the historical study of war; the tactics and techniques of maneuver warfare; risk-management assessment; force protection; and the study of USMC history. The intent of cultivating mental discipline is to produce Marines who are capable of understanding and handling the complexity of modern warfare; tactically and technically competent; capable of decisionmaking under any combat condition; constantly thinking and situationally aware; and who possess the virtually instinctive impulse to do the right thing, for the right reason, in the right way. Situational awareness enables the Marine to perceive tactical and strategic opportunities amid the fog and friction of war and capitalize on them by appropriate, timely combat action. A Marine without such situational awareness is a liability on the battlefield. Philosophy professor Shannon French notes, We should base our decision on awareness rather than on mechanical habit. That is, we act on keen appreciation for the essential factors that make each situation unique instead of from conditioned response. We must have the moral courage to make tough decisions in the face of uncertainty and to accept full responsibility for those decisions when the natural inclination would be to postpone the decision pending more complete information. To delay action in an emergency because of incomplete information shows a lack of moral courage. We do not want to make rash decisions, but we must not squander opportunities while trying to gain more information.2 Character discipline. General Robert H. Barrow said, Success in battle is not a function of how many show up, but who they are.3 To develop and reinforce character, MCMAP emphasizes the study

of ethics and respect for and participation in USMC traditions. To train a large group of people to kill while ignoring the ethical and character aspects of such conduct is to create an unruly, dangerous mob. The ethical- and character-development component is therefore imperative for creating a disciplined, capable, and professional military force. To properly fight the Global War on Terrorism, in which the rules are not always clearly defined, military leaders must reinforce and strengthen the morals and ideals of those trained as warriors to prevent their becoming like the terrorists they confront. Without an inculcated code of ethics, U.S. warriors might win the war and still lose in the court of world opinion if the methods they use are dishonorable. MCMAP aims to develop self-discipline and selfcontrol to restrain oneself in the heat of the moment and to use force responsibly. Developing the USMC warrior ethos includes mentoring values and shaping a long-term, individual commitment to the USMC and the values it represents. These activities are designed to instill an ethical dimension that places individual achievement in the context of continuing an old, honorable, warrior tradition. Development activities include leaders engaging with troops and participating in ceremonies and educational activities such as officer and noncommissioned officer (NCO) development case studies, guided discussions, mentoring programs, and social events, with a strong emphasis on common heritage and respect for other customs, courtesies, and traditions that complement the USMC core values of honor, courage, and commitment. Other programs teach citizenship and give counsel on personal and family obligations, safety, and risk management to help Marines become lethal warriors while developing a sense of place and mission, maturity, responsibility to the community, and self-discipline. Character development might be the most critical component in a Marines development. What makes MCMAP a complete program is the synergy of the mental, physical, and character disciplines, all of which are inextricably linked to advancing in the belt-ranking system. Commanders must certify that the Marine meets annual training requirements; has completed the prerequisites of each specific belt level; and possesses the necessary maturity, judgment, and moral character. This ensures that, as a Marine develops

MILITARY REVIEW

November - December 2004

23

the physical skills to make him a lethal warrior, he also develops commensurate maturity and selfdiscipline to conduct decentralized missions on the modern battlefield.

Gaining Respect

In todays society, many 18- to 20-year-old youths are members of gangs or participate in other nonproductive, destructive groups in search of personal identity, peer recognition, and respect. MCMAP aims to impress on young people coming from such environments that to be respected one must be respectable. MCMAP clearly defines the USMC ideal of what is respectable behavior to Marines of all ranks. The introductory training in which Marines are immersed during boot camp, Officer Candidate School, and the basic school often has a profound effect synchronizing the moral compass. However, such training does not complete young peoples transformation. They might need to shed 20 years of counterproductive values and beliefs (good or bad). They need continuous, ongoing training and education to reinforce and complete their inculcation. French says, In many cases, this code of honor seems to hold to a higher ethical standard than required for an ordinary citizen within the general population of the society [he] serves. The code is not imposed from outside. The warriors police themselves with strict adherence to these standards. Military units cannot function well, especially in combat environments if the members of the unit are not scrupulously honest with each other. . . . The code of a warrior not only defines how he should interact with his own warrior comrades, but also how he should treat other members of his society, his enemies, and the people he conquers. The code restrains the warrior. It sets boundaries on his be-

havior. It distinguishes honorable acts from shameful acts [and protects the warrior] from serious psychological damage.4 The USMC expects its warrior code to enable Marines to be effective warriors and have fewer problems after they return from conflict.

Mentoring

Young warriors must have a readily available mentor to help them formulate and solidify morals and values during times of peace so when they are in combat or high-stress situations they have beliefs on which to call, rather than acting impulsively in the heat of the moment. Instilling such beliefs in young Marines gives them a moral compass that will speed their decision process, especially when they are under stress, when time is short, or both. MCMAPs purpose is to strengthen the Marine Corps by inculcating a warrior spirit that embraces every aspect of a marines lifestyle and actions by combining rigorous mental, spiritual, and physical training in a synergetic program that inculcates Marine Corps values and focuses on mastering unarmed as well as armed combat skills. The result is a warrior imbued with the ability to deal with the moral dimensions of war and the ethical decisions of life and who is capable of winning on any battlefield. Against the backdrop of modern social changes and norms, this is how the military must prepare to successfully fight the three-block war, ensure success during the final 500 meters of combat, and win the Nations future battles. The goal is to make more-responsible, effective Marines, and better citizens. Marines deployed around the world are not only warfighters or peacekeepers, they are symbols to the world of what America stands for. MR

NOTES

1. U.S. Marine Corps (USMC), Small Wars Manual (Washington, DC: Headquarters, USMC, 1940). 2. USMC Doctrinal Publication 1, Warfighting (Washington, DC: Headquarters, USMC, 1997), 86. 3. GEN Robert H. Barrow, remarks before the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg, 2 June 1981. 4. Shannon E. French, The Code of the Warrior-Exploring Warrior Values Past and Present (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2003), foreword x, xi; 4. See also USMC, Close-Quarters Combat Manual (Boulder, CO: Paladin Press, 1996); and World War II U.S. Marine Raiders, Shaping the Raiders, online at <www.usmarine raiders.org/shapingraiders.html> (1-1, 5-6), accessed 26 October 2004.

Captain Jamison Yi, U.S. Marine Corps is a CH46E pilot currently attending the Expeditionary Warfare School, Quantico, Virginia. He has served as a warfighting instructor at the Basic School and aide-de-camp for the commanding general of the Education Command.

24

November - December 2004

MILITARY REVIEW

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Episode 31: Holy Week in SpainDocument7 pagesEpisode 31: Holy Week in SpainDhananjay BaviskarPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Burning Issue of Quran1Document21 pagesThe Burning Issue of Quran1Bhavya VermaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Avisar (Dancing Solo in The Lebanese Mud)Document9 pagesAvisar (Dancing Solo in The Lebanese Mud)Seung-hoon JeongPas encore d'évaluation

- Mother Teresa Quotes18Document1 pageMother Teresa Quotes18reader_no_junkPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- German War CodeDocument40 pagesGerman War CodedanilobmluspPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- King LearDocument10 pagesKing LearStefaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Malaysia International Shipping Corporation v. Sinochem International Co. LTD, 436 F.3d 349, 3rd Cir. (2006)Document28 pagesMalaysia International Shipping Corporation v. Sinochem International Co. LTD, 436 F.3d 349, 3rd Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Lumanog and Santos Vs The Philippines (Case Summary)Document1 pageLumanog and Santos Vs The Philippines (Case Summary)Ma. Fabiana GarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Petitioners, vs. HEIRS OF ROBERTO CUTANDA, Namely, GERVACIO CUTANDADocument7 pagesPetitioners, vs. HEIRS OF ROBERTO CUTANDA, Namely, GERVACIO CUTANDAayleenPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Waiver and Transfer of Rights BlankDocument2 pagesWaiver and Transfer of Rights BlankEric Echon100% (5)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- StabilityDocument8 pagesStabilitySalwan ShubhamPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Chi Ming Tsoi vs. CADocument3 pagesChi Ming Tsoi vs. CAneo paul100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Tartakovsky DmitryDocument391 pagesTartakovsky DmitryRocsana RusinPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- ChildOnMove Rohingya PDFDocument20 pagesChildOnMove Rohingya PDFAlexPas encore d'évaluation

- Empowerment Technologies Activity #2Document4 pagesEmpowerment Technologies Activity #2JADDINOPOLPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Operation Urgent FuryDocument40 pagesOperation Urgent FurygtrazorPas encore d'évaluation

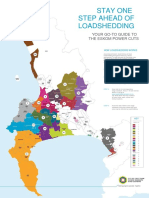

- Load Shedding All Areas Schedule and MapDocument2 pagesLoad Shedding All Areas Schedule and MapRobin VisserPas encore d'évaluation

- Political Ideas: Case Study: Rwandan GenocideDocument7 pagesPolitical Ideas: Case Study: Rwandan GenocideWaidembe YusufuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- PSC Final Order For Wildcat PointDocument1 pagePSC Final Order For Wildcat PointODECCecilPas encore d'évaluation

- Clive Emsley - Crime, Police, and Penal Policy - European Experiences 1750-1940 (2007)Document298 pagesClive Emsley - Crime, Police, and Penal Policy - European Experiences 1750-1940 (2007)Silva PachecoPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Alice in Wonderland - Short Story For KidsDocument9 pagesAlice in Wonderland - Short Story For KidsLor JurjamPas encore d'évaluation

- Obligations & ContractDocument38 pagesObligations & ContractFrancis Nicolette TolosaPas encore d'évaluation

- DONE Crimes Against Liberty and SecurityDocument4 pagesDONE Crimes Against Liberty and SecurityChristian Ivan Daryl DavidPas encore d'évaluation

- Cases Crimlaw IDocument258 pagesCases Crimlaw Ishopee onlinePas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- ADDITIONAL CASES FULL and DIGESTSDocument17 pagesADDITIONAL CASES FULL and DIGESTSjannagotgoodPas encore d'évaluation

- The Interplay Between U.S. Foreign Policy and Political Islam in Post-Soeharto IndonesiaDocument35 pagesThe Interplay Between U.S. Foreign Policy and Political Islam in Post-Soeharto IndonesiaSaban Center at BrookingsPas encore d'évaluation

- ComplaintDocument6 pagesComplaintEisley Sarzadilla-Garcia100% (2)

- Blaw Week 3 - ConsiderationDocument4 pagesBlaw Week 3 - ConsiderationKenny Ong Kai NengPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Lexington Police ReleaseDocument2 pagesLexington Police ReleaseWSETPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 Floor Legislative Building, Brgy. Sta. Elena, Marikina CityDocument2 pages4 Floor Legislative Building, Brgy. Sta. Elena, Marikina CityFranco Angelo ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)