Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Evaluation of A Summer-School Program For Highly Gifted Secondary-School Students: The German Pupils Academy

Transféré par

Matija KormanDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Evaluation of A Summer-School Program For Highly Gifted Secondary-School Students: The German Pupils Academy

Transféré par

Matija KormanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

European Journal of Psychological Assessment, Vol. 18, Issue 3, pp.

214228

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of aHogrefe & Huber Publishers EJPA 18 (3), 2002 Summer-Scho ol Program

Evaluation of a Summer-School Program for Highly Gifted Secondary-School Students: The German Pupils Academy

Heinz Neber and Kurt A. Heller

University of Munich (LMU), Germany

Keywords: Gifted education, program evaluation, summer school programs

Summary: The German Pupils Academy (Deutsche Schler-Akademie) is a summer-school program for highly gifted secondary-school students. Three types of program evaluation were conducted. Input evaluation confirmed the participants as intellectually highly gifted students who are intrinsically motivated and interested to attend the courses offered at the summer school. Process evaluation focused on the courses attended by the participants as the most important component of the program. Accordingly, the instructional approaches meet the needs of highly gifted students for self-regulated and discovery oriented learning. The product or impact evaluation was based on a multivariate social-cognitive framework. The findings indicate that the program contributes to promoting motivational and cognitive prerequisites for transforming giftedness into excellent performances. To some extent, the positive effects on students self-efficacy and self-regulatory strategies are due to qualities of the learning environments established by the courses. Even though such investigations repeatedly have been in demand, the evaluations of programs for highly gifted students have been strongly neglected (Callahan, 2000; Hany, 1988). Admittedly, there is no ideal design for evaluating gifted programs, and studies should be considered as singular approaches adapted to the complexity and specifity of a particular program. A further difficulty arises from the nonavailability of real control groups in evaluating programs for gifted students. In addition, evaluations of existing programs have to meet administrative constraints, which provide restrictions on contents and methods of the study. Finally, evaluation studies are confronted with possible negative reactions from administrators and staff (Carter, 1991; Hunsaker & Callahan, 1993).

Introduction

Promoting highly gifted students in regular, heterogeneously composed classrooms is difficult to realize and rather limited in its effects (Heller, 1999, 2001; Neber, Finsterwald & Urban, 2001). For these reasons, special programs have been developed in order to complement regular education. The requirements, objectives, and methods of such programs often remain unspecified, and are formulated on rather general levels. As a consequence, the same program may be implemented in various ways. For this reason, empirical studies are required to contribute by describing the programs, providing data on their implementation, and measuring their effects.

EJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers DOI: 10.1027//1015-5759.18.3.214

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of a Summer-School Program

215

These features may explain why program evaluations focus mainly on the effects and products of programs for gifted students, whereas the process evaluations of instructional procedures and the cognitive activities of participants in these programs have been neglected. But process evaluation studies are required to determine causal variables that might explain the effects and provide information for improving the program (Scriven, 1981). More elaborated program evaluations serve as additional descriptive and explanative functions (Sechrest & Figuerdo, 1993). Therefore, evaluators of programs for gifted students should not expect only to answer already specified questions, but to formulate and prioritize their own questions and topics for their evaluation studies (Callahan, 1993).

The Program

These consequences also apply to the evaluation of summer-school programs for highly gifted students. By design, summer schools are short-term, one-shot programs attended by highly gifted students generally only once in the course of their academic career (Olszewski-Kubilius, 1989). Originally, summer schools for highly gifted students served to accelerate the educational pursuits of high-school students (Robinson, 1983). Students who are identified as being highly gifted get access to the program and decide to participate in one of the advancedlevel courses offered. In these courses, the pace and level of difficulty are generally far above the normal highschool level. The students attend a course together with 1015 other highly gifted and interested peers. Courses are guided by two teachers or a teacher and an assistant, who perform all teaching functions and serve as models of domain-specific experts. The teachers decide on the contents of the course, and provide content-related materials to prepare the students in advance. Teaching and learning is preferably organized as project work aiming at the production of team-based professional products like reports, presentations, poster sessions, musical compositions, computer programs, or stage plays (Feldhusen, 1991). The German Pupils Academy (Deutsche SchlerAkademie) is an example of a cognitively challenging, 17-day residential summer program for 1618-year-old secondary-school pupils with participants from all parts of Germany and about 5% from other European countries. Generally, like other summer-school programs, its goal is to contribute in transforming giftedness into talents, mainly as high performances or excellence within specific domains (Olszewski-Kubilius, 1989). The implemented system of courses represents the most impor-

tant component of the summer-school program, and it serves to expand cognitive, motivational, and social experiences of the participants. In this respect, the German Pupils Academy is an enrichment and not an acceleration program. The participating highly gifted students should experience their intellectual strengths and weaknesses, further intensify academic interests, and develop cognitive as well as motivational requirements for being able to make their own reliable decisions on their future higher education goals (Goldstein & Wagner, 1993; Persson, Joswig & Balogh, 2000). Pupils get access to the program by recommendation from principals or teachers of their secondary schools (German Gymnasium) or by having successfully participated in one of the demanding national competitions in Germany. The program administrators then decide on the final acceptance of about one half of the 15002000 applicants.

Aims and Functions of the Program Evaluation

This residential program which takes place during summer vacations at several locations throughout the country was started in 1988. In 1993 and on behalf of the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) the current planned and implemented program was to be summatively evaluated to provide information as a basis to decide on the continuation of the program (BMBF, 1992; Heller, 1993). We subdivided the project into two main evaluation tasks. The first task consists of the program evaluation itself, describing components of the summer school and measuring its short-term effects (Heller & Neber, 1994) and the long-term impact on higher education careers of former participants of the program (Neber & Heller, 1996a). The second evaluation task relates to the identification of highly gifted students as participants of the summer school. The corresponding study focused on the quality of teacher nominations of students. This is the most crucial component in identifying participants of the program for most of the participants (about 80%) receive access based on teacher decisions about their level of giftedness (Neber & Heller, 1995, 1996b). The present text exclusively informs about the first part of the program evaluation. Features of programs for gifted students listed above apply to this summer program. Here, too, required characteristics of the participants, objectives of the program, and instructional approaches of the courses were neither clearly specified nor theoretically derived. For these reaEJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

216

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of a Summer-School Program

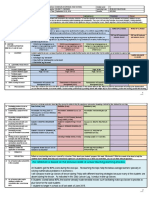

Table 1. Program evaluation: types, functions, objects, methods, and samples. Types Input Functions Descriptive Object/Content/Question Entry characteristics of participants (cognitive, motivational, social, demographic) Are participants highly gifted? Checking for social biases Characteristics of courses (learning environment) Methods Objective and selfreport instruments Participants Participants (n = 252); rejected applicants (n = 70)

Evaluative

Comparison of groups Comparing with standards (giftedness) Self-report instruments Convergent measurements (participants and teachers) Participants (n = 252); teachers of courses (n = 22)

Process

Descriptive

Evaluative

Do course characteristics meet needs of highly gifted learners?

Comparisons with standards of gifted education Comparisons of convergent measures Pre-post measures (short-term effects) Questionnaires Participants (n = 252); teacher evaluations of participants (n = 174)

Product

Descriptive

Effects on cognitive, motivational, self-system, and social characteristics of participants (study 1: short-term effects; study 2: effects on higher education) Does participation in the summer program contribute to transform competence into performance (giftedness into talent)? Which characteristics of courses/program and entry characteristics of participants contribute to the effects?

Evaluative

Explanative

Regression analyses with input-, processand product variables

sons, program evaluation cannot only aim at measuring some effects. It must contribute to describing the program, to deciding on entry characteristics required of the participants, to specifying objectives and intended effects of the program, and even contribute to providing explanations for possible effects. Thus, this program evaluation has descriptive, explanative, and evaluative functions. In order to meet these goals and functions, the CIPP model (Stufflebeam, 1983) was chosen as a framework of the program evaluation. Accordingly, four types of evaluation are distinguished: context, input, process, and product. These correspond to the phases of program deEJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

velopment considered the most preferable criteria for classifying types of program evaluation (Mittag & Hager, 2000). The CIPP model does not focus only on effects, but enables a description of the program and its components, provides information to explain effects, and, in the past, proved to be an adequate approach in evaluating gifted programs (Carter, 1991). Because the summer-school program had already been implemented, a prospective context evaluation that includes decisions on the program conception could not be performed. The program evaluation focused on the inputs, processes, and products of the already existing summer school. Each of the three types of evaluation served several

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of a Summer-School Program

217

functions. First, inputs, processes, and products of the program had to be described by applying objective and self-report instruments. Second, the descriptive results were evaluated by comparing groups, subgroups, convergent measures, and by relating the results to assumptions and findings about giftedness and its promotion (Table 1). The first study on program evaluation focuses on the actual summer school and its immediate effects on the participating students.

Method

Two samples of secondary-school students were included (Table 1). The first main sample (n = 252) consisted of male (n = 133) and female (n = 119) students accepted to participate in the summer program at three residential areas. The second sample (n = 70) consisted of rejected applicants serving as a comparison group. The inclusion of this group of nominated students who did not take part in the program enables minimal control required in program evaluation studies (Hager, 2000). As in other studies on gifted program, a true control group could not be formed. With the main sample, data collection took place in two phases. The pretest phase took place on the first day of the program (immediately before beginning the coursework) and the posttest was conducted two weeks later on the last day of the program, immediately after finishing the courses. In pre- and posttests, all data were gathered in groups consisting of 2535 participants. With the rejected applicants from the second sample, data were collected only once by mailing a portion of the same self-report instruments (Table 2) applied in pretesting the main sample (n = 70 or 64% of n = 110 returned the questionnaires).

Program Evaluation

Input Evaluation

The objects of the input evaluation were the entry characteristics of students participating in the summer-school program. Information was required about the level of giftedness, performance-mediating cognitive and motivational characteristics, and socio-educational variables of the students which might indicate possible biases in accepting applicants to the program. Intellectual giftedness was measured by quantitative, verbal, and figural tasks of the German version of the

Cognitive Abilities Test (CAT; Heller, Gaedike & Weinlder, 1985). The norm-referenced total score for cognitive abilities (T-score) is taken as a general measure of intellectual competence. The reference group for calculating this score is the population of secondary-school students of the same grade levels (T = 50, which corresponds to the mean CAT-score of this reference group). Decisions about further variables were based on Gagns (1993) model of giftedness and talent. Giftedness is considered a competence that could and should be transformed into talents or domain- and subject-specific performances. This transformation is dependent on environmental and intrapersonal catalysts. Environmental catalysts (e. g., significant interventions) remain rather unspecified in this model. Intrapersonal catalysts are restricted to motivation and personality as nonability characteristics. It was decided to measure intrapersonal catalyst variables in this study. In order to specify and increase the spectrum of such catalyst variables, Gagns general model was complemented by Pintrich and Schraubens (1992) model for explaining high achievement in classrooms. Accordingly, motivational beliefs and learning strategies were measured as intrapersonal catalysts that may support the utilization of intellectual giftedness and its transformation into course-specific performances at the summer-school program. Self-efficacy and intrinsic value, both specifically related to the domain of the courses attended at the summer school, were measured as motivational beliefs by subscales of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (Pintrich & DeGroot, 1990). As additional motivational variables, causal attributions of success and failure were measured by single items developed by the authors. One item expressed possible success and the other possible failure in the domain of the chosen course. Each item was to be answered by selecting one of four attributional alternatives (effort, ability, task difficulty, chance) which were based on the attributional model of Weiner, Frieze, Kukla, Reed, Rest, and Rosenbaum (1971). Because attributions for each situation were measured by a single item, no reliability estimates could be obtained. Learning strategies were investigated by a self-report scale developed by the authors. The scale covers seven of nine categories of self-regulatory learning strategies as distinguished by Zimmerman and Martinez Pons (1986). As additional catalyst variables, we included preferences for cooperative and for competitive learning in the input evaluation. These measures specifically relate to the learning environments of this summer-school program, whose courses require working in teams, productive interactions, mutual help, and division of labor among other highly gifted peers. The preference for cooperative learning might be taken as a determinant of the learning performance in these situations. Preferences for

EJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

218

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of a Summer-School Program

Table 2. Input evaluation: measures and subjects. Type and phase of Evaluation Input Evaluation (pretest) Object of Evaluation Students/ Participants Instrument/ Author Socio-educational status variables (authors) Summer school related Interests (authors) Variables (no. of items) Occupation father Education father Education mother Knowledge (3) Communication (3) Leisure time (3) .43 .54 .58 Example item Relia- Subjects bility (n) () Participants (n = 252) Participants + rejected applicants (n = 322) Participants (n = 252) How important is for learning on the domain of the course: . . . to memorize something .69 . . . summarizing what was heard/read .75 . . . to make available many sources .43 . . . to set up clearly specified goals .61 . . . note what was not understood .44 . . . after having understood some- .54 thing, checking if you really know it. . . . explaining something to other .71 students. I think I will receive a good grade .86 in this class It is important for me to learn .77 what is being taught in this course If I solve a difficult task well in the course, this is due to: effort ability easiness/difficulty of the task chance If I cannot solve a task in the course . . . Participants + rejected applicants (n = 322) Participants + rejected applicants (n = 322) Participants + rejected applicants (n = 322)

Cognitive Ability Test Cognitive abilities (Heller, Gaedike & total T-score Weinlder, 1985) Self-regulated learning strategy questionnaire (authors) course-related: Memorizing (5) Transforming (10) Information search (4) Planning (7) Self-monitoring (4) Self-evaluation (6) Communicating (8) Motivated Learning course-related: Strategies Question- Self-efficacy (9) aire (MSLQ; Pintrich & De Groot, 1990) Intrinsic Value (9) Causal Attribution (authors) course-related: Success attribution (1) Failure attribution (1) Learning Preference Scale for Students (LPSS) (Owens et al., 1980; Neber, 1994) course-related preference for: Cooperation (7) Competition (6)

Participants + rejected applicants (n = 322)

I am glad to help others in a group .48 I learn faster if I try to be better .76 than others

cooperative and for competitive learning were measured by the German version of the Learning Preference Scale for Students (Li & Adamson, 1992; Neber, 1994). All cognitive and motivational intrapersonal catalyst variables in this study were explicitly related to the domain of the course attended by the participant. With rejected applicants these variables were related to the domain of their prospectively chosen but then not attended course. The context- and domain-related measurement of such variables by customized tools is based on recomEJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

mendations of Garcia and Pintrich (1996) who propose to investigate motivational beliefs and learning strategies not as general constructs but related to specific subjects and situations. Table 2 summarizes variables and samples of the input evaluation. Results Socio-educational status. 72% of the fathers and 54% of the mothers of the participants had graduated from college or a university. A majority of the fathers work as

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of a Summer-School Program

219

Table 3. Intrapersonal catalyst variables of participants and rejected applicants. Variablesa Summer school related interests Knowledge acquisition Communication Leisure time Self-regulated learning strategiesa Memorizing Transforming Information search Self-planning Self-monitoring Self-evaluation Communicating Motivational beliefsa Self-efficacy Intrinsic value Learning preferencesa Cooperation Competition

a b

Participants M SD

Rejected Applicants M SD

Fb

2.63 3.20 2.36

.50 .46 .70

2.77 2.74 2.47

.57 .68 .73

4.0 33.0 1.1

.04 .00 .29

.02 .12 .00

2.28 3.00 2.96 2.54 2.77 2.55 2.92 2.37 3.21 2.83 2.42

.54 .44 .54 .44 .47 .44 .42 .61 .45 .29 .60

2.49 3.09 3.20 2.68 2.97 2.72 2.90 2.62 3.30 2.90 2.61

.59 .49 .62 .49 .50 .45 .41 .58 .43 .30 .63

7.7 2.2 10.2 5.9 9.4 7.9 0.0 10.7 3.3 3.1 6.7

.01 .14 .00 .02 .00 .00 .94 .00 .07 .08 .01

.02 .01 .03 .02 .03 .02 .00 .03 .01 .01 .02

variables relate to the domain of the course attended (participants) or intended (rejecteds); all variables are measured on 4-point scales. univariate F; df: 1,264

officials and in high-level white-collar jobs (63%) or are self-employed (18%). Altogether, participants family background is characterized by a level of education far above the average. Intellectual giftedness. In the Cognitive Abilities Test the participants attained a mean norm-referenced total score of MT = 65.2 (SDT = 12.7), which corresponds to an IQ of 123 (Heller et al., 1985, p. 160). Accordingly, the intellectual giftedness of the participants is far above average, beyond the 98th percentile of their age group, and represents the top 6% of German secondary-school (Gymnasium) students of comparable grade levels. MANOVAs were performed with each group of intrapersonal catalyst variables and one between-subject factor (participant and rejected applicant). Because all variables were measured on a 4-point scale, the nonstandardized data were used for further analyses. There were statistically significant differences between participants and rejected applicants in all groups of variables (Table 3). Interests in participating in the summer-school program differed considerably between both groups (multivariate F = 17.0; p = .00; 2 = .15). Compared to rejected applicants, participants interest in acquiring domainspecific knowledge was weaker, whereas interest to meet

and communicate with other students was stronger. Both groups were equally less interested in applying to the program for leisure-time reasons. Differences in terms of course-domain related learning strategies (multivariate F = 2.1; p = .04; 2 = .05) were found for simple memorizing activities, and for all of the more advanced self-regulatory learning strategies (Table 3). All of these differences favor rejected applicants. In addition, the rejected students perceived themselves as more self-efficacious on their chosen course domains, and their preference for competitive learning was stronger than with the participating students. Nevertheless, both groups preference for cooperative learning on course-related domains was stronger than the preference for competitive learning (Table 3). The attributional data indicate that both groups almost exclusively explain success by internal variable and controllable factors (effort) or by stable causes (ability) (Figure 1). In explaining possible failures, both groups prefer controllable factors either referring to external causes (task difficulty) or variable internal factors (effort). These tendencies correspond to other findings with gifted groups of students, whereas nongifted and lowachieving students overestimate ability as a cause of failures (Dai, Moon, & Feldhusen, 1998). In Weiners terms (1984), participants and rejected applicants use extremeEJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

220

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of a Summer-School Program

Figure 1. Causal attributions of possible success and failure in course-domains by participants and rejected applicants.

ly positive attributional patterns in dealing with results of their course specific performances. Nonparametric tests of the frequency distributions of the attributional categories revealed no differences between both groups of subjects (success: U = 7695; p = .60; failure: U = 7382; p = .39). The input evaluation confirms that the participants represent a group of highly gifted students. There is considerable consensus in the literature that belonging to the top 2% in intellectual abilities is a strong argument for this inference. In addition, the participants seem to be perfectly fit for the requirements of the courses offered at the summer school. They are strongly and intrinsically interested in the topics, tend to apply higher-level processing strategies in searching and analyzing topic-related information, and they are willing to learn together with others. Such motivational and cognitive characteristics have been found in other studies with gifted students (Chan, 1996; Zimmerman & Martinez Pons, 1992). Nonetheless, some caution might be exercised in drawing conclusions about the process of admitting students to the program. First, accepted students represent an above-average social-educational level. This tendency might not be interpreted as a socially biased procedure in selecting participants, but may indicate more generally biased tendencies in the educational system. Family relationships that offer participation in classical culture seem to be strong predictors of performances at school, particularly in countries like Germany (OECD, 2001). Second, according to these results, rejected applicants seem to meet requirements for utilizing intellectual competence to at least the same extent as the accepted participants of the summer-school program. Some of the cognitive and motivational variables measured as intrapersonal catalysts are even more positively developed than with participants. In another gifted program evaluation study focused on university students we found the same differences between scholarship recipients and nonproEJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

moted talented students and interpreted this as a self-protecting effect (cf. Heller & Viek, 2000). Both groups cognitive and motivational prerequisites for transforming competence into domain-specific performance considered in this study are extremely strong. Thus, these data provide no arguments for not admitting the rejected applicants to the program.

Process Evaluation

Process evaluation assesses the delivery of a program, and whether it is implemented as intended (Scheirer, 1994). In gifted education this type of evaluation often remains neglected for several reasons. As in the case of the summer-school program, practical considerations restrict the scope of possible contents and methods and the intended program is not well enough specified to provide criteria for evaluating its implementation. The current process evaluation focused on some important aspects concerning the interaction of giftedness and characteristics of the learning environment. Decisions on such aspects were based on the literature on learning and instruction of highly gifted students. Impressive support for establishing special learning environments for gifted and high-achieving students was already provided by aptitude-treatment interaction studies (Corno & Snow, 1985). The construct of aptitude used by these investigators includes intellectual abilities, academic motivation, and learning styles. As the input evaluation has shown, the participants of the summer-school program are far above the average for their grade levels in all these characteristics, and are to be considered as high aptitude students. Accordingly, instructional treatments should offer high amounts of self-direction, and should be based on the principles and methods of discovery learning (Corno & Snow, 1985; Neber, 1982, 2001b; Neber & Schommer-Aikins, 2002). Similar demands on designing instruction for highly gifted learners have been made by proponents of gifted education (Heller & Hany,

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of a Summer-School Program

221

Table 4. Process evaluation: measures and subjects. Type of Evaluation Process Group of variables Instructional methods Variables (no. of items) Discovery learning (4) Direct instruction (5) Example item Subjects Reliability .52 .75 (intended) .75 (actual) .80 .66 (intended) .59 (actual) .69 .43 (intended) .45 (actual) .67 .54 (intended) .61 (actual) .79 .41 (intended) .63 (actual) .63 .68 (intended) .46 (actual) .39 .58 (intended) .65 (actual) .58 .55 (intended) .44 (actual)

Students formulate own Students assumptions and hypotheses. Teachers A new subject is presented Students only after having exactly Teachers specified the learning objectives. Students self-evaluate their performances. Students request help from classmates. Students exactly reproduce the content of the course. Students Teachers Students Teachers Students Teachers

Self-regulation

Self-regulatory activities (5) Communicative activities (4) Low level (2)

Cooperation

Cognitive Objectives

High level (3)

Students integrate information Students from different sources. Teachers Students learn to listen attentively. Students Teachers

Affective Objectives

Low level (2)

High level (3)

Students are actively interested Students and provide own contributions Teachers to the course.

1996; Heller, 1999, 2001; Hoekman, McCormick, & Gross, 1999; Kokot, 1999; Neber, 2001a; Renzulli, 2000; Winner, 1997). Besides stressing self-regulation and discovery learning, programs for gifted learners should provide highlevel cognitive challenges while contributing in increasing the students intrinsic motivation. Both of these aspects are covered by taxonomies of educational objectives in cognitive and affective domains which have been frequently applied in designing models of gifted education (Bloom, 1985; Maker & Nielson, 1995). Accordingly, the courses offered at the summer-school program should aim at attaining high-level cognitive and affective objectives. The objects of the process evaluation were the learning environments provided by the courses at the summer school. There was a general shift away from only considering objective features of learning environments to measuring subjectively perceived characteristics. This is because of the impact of social-cognitive psychology, the basic assumption of which is that activities and effects of

learning are strongly determined by subjective perceptions of the environment (Schunk, 1992). Consequently, perceptions of participating students and teachers involved in the courses at this summer school were measured by a self-report scale developed by the authors. The scale covers instructional methods, studentsself-regulation, cooperation, and curricular objectives as characteristics of the courses (Table 4). In the posttest, students (n = 249) retrospectively evaluated these characteristics on four-point scales for the courses they had just attended. In addition, teachers (n = 22) of the courses received an adapted version of the scale and responded twice to each item. The first teacher rating focused on intended features of their courses, and the second rating on the actual implementation of these features. The inclusion of student, teacher, and double ratings allows for several comparisons. Convergent student and teacher ratings increase the reliability of measures about conditions of learning. Comparing actual with intended teacher ratings provides information about the impleEJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

222

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of a Summer-School Program

Table 5. Process variables of course-related learning environments measured with students and teachers. Variablesa Discovery learning Direct instruction Self-regulation Cooperation Objectives Low cognitive High cognitive Low affective High affective

a

Students M SD 3.0 3.1 2.9 3.2 3.3 3.1 3.0 2.9 .52 .62 .60 .53 .55 .54 .67 .61

Teachers M SD 3.3 3.1 3.1 3.3 3.0 3.5 3.3 3.1 .58 .55 .41 .48 .72 .41 .60 .51

Fb 7.8 0.0 1.5 1.4 7.1 10.6 3.9 0.9

p .01 .95 .21 .23 .01 .00 .04 .32

2 .03 .00 .01 .00 .03 .04 .01 .00

variables relate to the course attended/held; all variables measured on four-point scales. bunivariate F; df: 1,269

mentation of the individual instructional approaches. In general, Fraser, McRobbie, and Giddings (1993) suggest using discrepancy measures resulting from comparisons for optimizing learning environments.

Results

The results presented in Table 5 indicate that the courses at the summer-school program are characterized by multiple teaching methods, and by objectives at diverse levels. In general, self-regulation and in particular cooperation seem to be frequently enabled activities in the courses. For comparing student and teacher ratings a MANOVA with one between-subject factor (student and teacher) was performed resulting in a very significant multivariate difference between the perceptions of both groups (multivariate F = 4.93; p = .00; 2 = .13). The univariate tests reveal that mainly cognitive characteristics of teaching and learning in the courses are concerned (Table 5). Teachers view discovery learning as a much stronger instructional approach to their courses than do students. The same applies to the higher cognitive objectives analyzing, synthesizing, applying, and evaluating which are the dominating objectives according to the teachers. In contrast, students perceive the courses as being dominated by low cognitive objectives like rote learning and receptively understanding the contents. This is further supported by comparing student pretest ratings of the expected difficulty of their courses and their retrospective posttest ratings of the actual difficulty. Accordingly, the expected difficulty (M = 3.09; s = .55) was significantly higher than the actual difficulty (M = 2.94; s = .61; repeated measures F = 11.6; p = .00; 2 = .05). For comparing intended and actual teacher ratings of the course characteristics paired samples t-tests were calculated for each of the eight pairs of variables. No sigEJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

nificant differences were found between intended and actually implemented characteristics of the courses. Obviously, teachers realized their courses as planned, and did not change their approaches. In sum, the teachers perceived the cognitive level of the courses higher than it is perceived by the students who even seem to expect higher than the actual levels of cognitive challenges. There might be some room for further increasing the cognitive level of courses. On the other hand, the teaching staff is obviously well prepared for their instructional tasks and are able to design and implement learning environments for highly gifted learners.

Product Evaluation

The third type of evaluation performed in this study focuses on the output (Stufflebeam, 1983), effects, or impact of the program (Rossi & Freeman, 1993). As with the other types of evaluation, the contents and methods of the measurements had to be specified in the context of the constraints set by the natural conditions of the program. In assuming that the transformation of competencies into performance and talent (according to Gagn, 1993) is the main general purpose of the summer-school program, the participants should develop motivational and cognitive catalyst variables required for attaining high levels of excellence. Thus, the catalyst variables which had been measured in the input evaluation during the pretest were measured again in the posttest with the same sample of participants (see Table 2). For evaluating products of the German Pupils Academy this rather simple before/after reflexive design (Rossi & Freeman, 1993) seems to be appropriate for serving the intended descriptive and evaluative functions (Table 1). First, only two measurement periods were available. Second, minimal control of unknown interfering events is provided for as

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of a Summer-School Program

223

Table 6. Pre/post changes of intrapersonal catalyst variables. Variablesa Self-regulated learning strategiesa Memorizing Transforming Information search Self-planning Self-monitoring Self-evaluation Communicating Motivational beliefsa Self-efficacy Intrinsic value Learning preferencesa Cooperation Competition

a

Pretest M SD

Posttest M SD

F_b

2.28 3.00 2.95 2.54 2.77 2.55 2.92 2.37 3.21 2.83 2.42

.54 .44 .54 .44 .47 .44 .42 .61 .45 .29 .60

2.34 3.07 3.20 2.61 2.91 2.71 3.02 2.69 3.30 2.89 1.93

.63 .53 .53 .52 .55 .50 .46 .67 .55 .48 .74

2.5 4.3 7.6 3.7 13.7 18.3 11.5 58.7 5.4 1.9 100.6

.12 .04 .01 .06 .00 .00 .01 .00 .02 .16 .00

.01 .02 .03 .01 .06 .07 .05 .19 .02 .01 .30

variables relate to the domain of the course attended; all variables are measured on four-point scales. bunivariate F

Figure 2. Causal attributions of possible success and failure in course-domains before and after attending the German Pupils Academy.

it is a residential program and there was only a short period of time between both measurements.

Results

The pre- and posttest means of the course related catalyst variables were compared (Table 6). For each group of variables, repeated measures MANOVAs were used to compare changes in scores from pre- to posttest. The multivariate tests indicate very significant differences for self-regulatory learning strategies (F = 4.3; p = .00; 2 = .12), motivational beliefs (F = 29.3; p = .00; 2 = .19), and learning preferences (F = 53.6; p = .00; 2 = .31). Seemingly, cognitive as well as motivational characteristics were influenced by attending the summerschool program. The univariate tests (Table 6) reveal some impressive effects on motivational beliefs and

learning preferences. Self-efficacy was much stronger in the posttest indicating a considerable growth in positive expectancies for high achievements in the domains of the attended courses. The relatively small increase in intrinsic value may be due to the already high level in the pretest. Concerning learning preferences, a sharp decline in the preference for competitive learning could be observed. In respect to learning strategies, the summerschool program seems to promote higher-level self-regulatory strategies on course domains whereas pre-post differences in low level strategies like memorizing were non-significant. The explanations of cognitive successes and failures in the courses by the participants remained rather stable (Figure 2). For success, the causal attribution patterns in pre- and posttests were almost identical. According to results of the Wilcoxon signed rank test, the distributions of attributions for success (Z = .66; p = .51) as well as for failure (Z = 1.11; p = .26) did not differ significantly.

EJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

224

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of a Summer-School Program

Table 7. Linear regression analyses examining predictors of effects of the German Pupils Academy. Changes in Self-efficacy Predictor variables t p Changes in Preference for Competitive Learning t p .09 .05 .09 .22 .06 .50 .03 .16 1.67 .79 1.43 3.54 1.01 8.17 .09 .42 .15 .00 .31 .00 Changes in Self-evaluation .01 .06 .47 .02 .13 .03 .06 .14 t .18 .97 7.28 .25 1.99 .52 p .85 .33 .00 .80 .04 .60 Course Achievementc .08 .03 .04 .01 .11 .10 .09 .01 t .92 .34 .48 .10 1.27 1.24 p .32 .73 .63 .92 .20 .21

Student entry characteristics Cognitive ability .11 1.89 .05 .01 .08 .94 Self-monitoringa .03 .43 .67 Self-evaluationa Self-efficacya .48 8.08 .00 Intrinsic valuea .03 .49 .62 Preference for .04 .68 .50 competitive learning a Learning environment characteristics Discovery learning a b .15 2.55 .01 High cognitive objectives a b .25 4.12 .00

a

.43 .66 2.54 .01

.92 .36 2.14 .03

1.07 .29 .11 .91

variable relates to the course domain, bstudent rating, cteacher rating

Seemingly, the participants of the summer school had already developed rather stable and optimal ways in dealing with personal experiences or achieving in challenging academic fields of achievement. Even though, no effects on causal attributions could be observed, participating in the German Pupils Academy had a rather impressive impact on cognitive and motivational characteristics which are considered as prerequisite internal catalysts for developing domain-specific excellence. In order to explain effects of the summer-school program and to serve the explanative function of the product evaluation, linear regression analyses with several effect variables as criteria were conducted. The first three regression analyses addressed intrapersonal catalyst variables which changed the most from pre- to posttest (selfefficacy, preference for competitive learning and selfevaluation). In the fourth regression analysis the criterion was the average score for achievement in the course. The score was based on n = 174 teacher ratings (four-point scale) of students achievement in their courses. More objective examinations, tests or performance measurements could not be taken, because the conception of the German Pupils Academy precluded such assessments. The philosophy is based on prior research that has shown that nongrading in classrooms fosters a positive social-emotional climate and contributes to developing intrinsic motivation (Church, Elliot & Gable, 2001). All regression analyses (method: enter) examined the predictive power of the same set of students entry-level characteristics as measured in the input evaluation (cognitive abilities, self-efficacy, intrinsic value, preference for competitive learning, self-monitoring and self-evaluation) and in the process evaluation by features of the

EJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

learning environment as measured by student ratings (discovery learning and high cognitive objectives). About 30% of the changes in each of the intrapersonal catalyst variables were explained by this set of variables (R2 = .28 for changes in self-efficacy and in preferences for competitive learning; R2 = .26 for changes in selfevaluation). In contrast, teacher rated achievement in the courses could not be predicted by these variables (R2 = .03). The findings depicted in Table 7 reveal that, in general, individual characteristics whose level is low relative to this group of students when applying to the summerschool program are strong predictors of changes in these characteristics. Thus, changes in domain-specific selfefficacy were stronger if prior self-efficacy was lower. In addition, these changes were significantly determined by the students cognitive abilities and by their perceived cognitive characteristics of the learning environment. Obviously, discovery learning and high cognitive objectives contribute in fostering positive changes in expectancies to be successful on course domains. In contrast, perceiving the cognitive objectives of the courses as being on high levels seems to disrupt the reduction of the preference for competitive learning. The same applies to high prior expectations to be successful on the course domain (high self-efficacy). The changes in self-evaluation which are clearly positive on average seem to be stronger with relatively low prior self-evaluators who are, at the same time, intrinsically motivated in the topics of the course. Perceiving cognitively high challenging tasks in the courses is another determinant of changes in self-evaluation activities in course domains. Altogether, the analyses with these change variables reveal that perceived characteristics within the learning

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of a Summer-School Program

225

environment interact with individual prerequisites of the participants. The same course environment may have different effects because of each participants entry level characteristics. Nevertheless, the results indicate that participants who possess relatively less-developed characteristics will develop in positive directions by attending the German Pupils Academy and that cognitive qualities within the learning environments of the courses contribute in these developments. Teacher-rated course achievements of their students could not be explained by this set of variables that, except for cognitive abilities, have been measured by students self-reports. It might be that teachers had developed subjective conceptions of achievement whose defining features are unknown. In order to get further information about determinants of this achievement variable the regression analysis was repeated with a new spectrum of teacher-evaluated student characteristics as predictors. These predictor variables resulted from a teacher rating scale developed by the authors, the 47 items of which were answered on a five-point Likert scale. A cluster analysis resulted in six clearly interpretable cluster variables: speed and level of learning, learning motivation, cooperation, prior knowledge about the topics of the course, disturbed communication and social anxiety. These six variables explained more than 80% of teacherrated course achievements of the participants (R2 = .86). Three predictor variables contributed significantly to this result: cooperation in the course ( = .49), learning motivation ( = .38), and negatively social anxiety ( = .11). Accordingly, nonproblematic communication and active involvement in course activities seem to be the strongest determinants of students achievements in the courses as seen by the teachers.

General Discussion

These investigations serve to contribute to deciding on the continuation of the program by providing information about several important aspects of the summerschool program. For these purposes, input-, process-, and product-evaluation studies were conducted. The input evaluation confirmed that highly gifted students get access to the program. The participants not only have high intellectual potentials, at the same time they have developed strong intrinsic interests in acquiring knowledge and skills on specific domains, have extremely positive attribution patterns for dealing with success and failure on academic domains at their disposal, and their family background is characterized by a high social-educational status. Nevertheless, problems remain in selecting participants for the program. Rejected appli-

cants seem to meet the same entry requirements, and no clear criterion for not accepting them was apparent from these investigations. Process evaluations focused on the courses offered and attended as the most important component of the German Pupils Academy. It was assumed that the general purpose of these courses is contributing to transforming intellectual competencies into excellent performances in their specific domains by developing intrapersonal catalyst variables. Students and teachers views of the learning environment characteristics required to attain these purposes were measured. These convergent measures yielded some discrepancies. Students perceive discovery learning and high-level cognitive objectives as less characteristic of the courses than teachers. There seem to be room for further increasing the cognitive level of the courses. The finding that teachers realized their courses exactly as intended and planned may be taken as an indicator of adequately staffing the summer-school program by teachers being skilled in instructing highly gifted students. The product evaluation focused on effects of the German Pupils Academy, which were investigated by applying a multivariate framework derived from the literature on giftedness. The first question was whether the program had some impact on individual cognitive and motivational prerequisites for utilizing the intellectual competencies necessary for attaining high levels of excellence. A second question dealt with possible intrapersonal and environmental factors in explaining the impact. Strong effects were achieved on domain-specific selfefficacy as a motivational belief required for high achievements in challenging fields of excellence. In addition, preferences for competitive learning were strongly reduced indicating an increase in willingness to work in teams on complex projects. Significant but weaker effects were found for the acquisition of domain-specific self-regulatory learning strategies that might be considered cognitive prerequisites for independent work on diverse academic fields. Very low or no effects were found for some motivational characteristics, because of the already developed high level of these characteristics prior to attending the summer-school program. Students course-domain-related intrinsic interests were already extremely strong, while their causal attribution patterns in dealing with domain specific successes and failures had been optimally developed. In these respects, no further improvements could be expected. The analyses of causes for these effects revealed that individual motivational and cognitive characteristics that are relative to this group of highly gifted students less well developed will be promoted by attending the summer-school program. Cognitive qualities of the learning

EJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

226

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of a Summer-School Program

environments realized in the courses contribute to these effects. Altogether, the German Pupils Academy can be considered an effective program in promoting highly gifted secondary-school students. But, as with other programs in gifted education, it seems to serve specific groups of highly gifted students. It is most adequate for students who are already strongly motivated, aim at acquiring insights and knowledge on specific domains, and are according to teachers views able to communicate efficiently with teachers and other highly gifted peers. Here, one feels intruded upon by what Merton (1968) called the Matthew effect in reference to a scripture from the Book of Matthew (Matthew 25:29 For unto every one that hath shall be given), which alleges a process of the accumulation of chances (Merton, 1973). For greater detail see Heller (2001). Acknowledgments This study was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Technology (BMBF) in Bonn. We especially thank Gnther Bumler, Michael Henninger and Leticia Hernndez de Hahn for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

References

Bloom, B.J. (1985). Developing talent in young people. New York: Ballantine Books. Bundesministerium fr Bildung und Wissenschaft (BMBW) (1992). Schlerakademie. Konzept und Erfahrungsbericht [The Pupils Academy: Conception and report on experiences]. Bonn: BMBW. Callahan, C.M. (1993). Evaluation programs and procedures for gifted education: International problems and solutions. In K.A. Heller, F.J. Mnks, & A.H. Passow (Eds.), International handbook of research and development of giftedness and talent (pp. 605618). Oxford: Pergamon. Callahan, C.M. (2000). Evaluation as a critical component of program development and implementation. In K.A. Heller, F.J. Mnks, R.J. Sternberg, & R.F. Subotnik (Eds.), International handbook of giftedness and talent (2nd ed., pp. 537547). Amsterdam: Elsevier. Carter, K.R. (1991). Evaluation of gifted programs. In N.K. Buchanan & J.F. Feldhusen (Eds.), Conducting research and evaluation in gifted education (pp. 245274). New York: Teachers College Press. Chan, L.K.S. (1996). Motivational orientations and metacognitive abilities of intellectually gifted students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 40, 184193. Church, M.A., Elliot, A.J., & Gable, S.L. (2001). Perceptions of classroom environment, achievement goals, and achievement outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 4354.

EJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

Corno, L., & Snow, R.E. (1985). Adapting teaching to individual differences among learners. In M.C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (pp. 605629). New York: Macmillan. Dai, Y.D., Moon, S.M., & Feldhusen, J.M. (1998). Achievement motivation and gifted students: A social cognitive perspective. Educational Psychologist, 33, 4563. Feldhusen, J.F. (1991). Saturday and summer programs, in N. Colangelo & G.A. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of gifted education (pp. 197208). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Fraser, B.J., McRobbie, C.J., & Giddings, G.J. (1993). Development and cross-national validation of a laboratory classroom environment instrument for senior high school science. Science Education, 77, 124. Gagn, F. (1993). Constructs and models pertaining to exceptional human abilities. In K.A. Heller, F.J. Mnks, & A.H. Passow (Eds.), International handbook of research and development of giftedness and talent (pp. 6988). Oxford: Pergamon. Garcia, T., & Pintrich, P.R. (1996). Assessing studentsmotivation and learning strategies in the classroom context: The motivated strategies for learning questionnaire. In M. Birenbaum & F.J.R.C. Dochy (Eds.), Alternatives in assessment of achievements, learning processes and prior knowledge (pp. 319339). Boston, MA: Kluwer. Goldstein, D., & Wagner, H. (1993). After school programs, competitions, school olympics, and summer programs. In K.A. Heller, F.J. Mnks, & A. H. Passow (Eds.), International handbook of research and development of giftedness and talent (pp. 593604). Oxford: Pergamon. Hager, W. (2000). Wirksamkeits- und Wirksamkeitsunterschiedshypothesen, Evaluationsparadigmen, Vergleichsgruppen und Kontrolle [Hypotheses on effectiveness and on differences in effectiveness, paradigms of evaluation, and control]. In W. Hager, J. L. Patry, & H. Brezing (Eds.), Evaluation psychologischer Interventionsmanahmen [Evaluation of psychological interventions] (pp. 180201). Gttingen: Hogrefe. Hany, E.A. (1988). Programvaluation in der Hochbegabtenfrderung [Program evaluation in promoting highly gifted students]. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht, 35, 241255. Heller, K.A. (1993). Frderungsantrag zur wissenschaftlichen Begleitung der Schlerakademie [Proposal for the evaluation of the Pupils Academy]. Munich: Institute of Psychological Assessment and Evaluation, University of Munich. Heller, K.A. (1999). Individual (learning and motivational) needs vs. instructional conditions of gifted education. High Ability Studies, 9, 921. Heller, K.A. (2001). Gifted education at the beginning of the third millennium. Australasian Journal of Gifted Education, 10, 4861. Heller, K.A., & Hany, E.A. (1996). Psychologische Modelle der Hochbegabtenfrderung [Psychological models in promoting highly gifted students]. In F.E. Weinert (Ed.), Enzyklopdie der Psychologie. Pdagogische Psychologie, Band 2: Lernen und Instruktion [Encyclopedia of psychology, Educational psychology, Volume 2: Learning and instruction] (pp. 477507). Gttingen: Hogrefe. Heller, K.A., & Neber, H. (1994). Evaluationsstudie zu den Schlerakademien 1993 [Evaluation study on the Pupils Academies in 1993]. Munich: Institute of Psychological Assessment and Evaluation, University of Munich.

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of a Summer-School Program

227

Heller, K.A., & Viek, P. (2000). Support for university students: Individual and social factors. In C.F.M. van Lieshout & P.G. Heymans (Eds.), Developing talent across the life span (pp. 299321). Hove: Psychology Press/Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis. Heller, K.A., Gaedike, A.-K., & Weinlder, H. (1985). Kognitiver Fhigkeits-Test (KFT 413+) (2nd ed.) [Cognitive Abilities Test (CAT)]. Weinheim: Beltz Testgesellschaft. Hoekman, K., McCormick, J., & Gross, M.U.M. (1999). The optimal context for gifted students: A preliminary analysis of motivational and affective considerations. Gifted Child Quarterly, 43, 170193. Hunsaker, S.L., & Callahan, C.M. (1993). Evaluation of gifted programs: Current practices. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 16, 190200. Kokot, S. (1999). Discovery learning: Founding a school for gifted children. Gifted Education International, 13, 269282. Li, A.K.F., & Adamson, G. (1992). Gifted secondary students preferred learning style: Cooperative, competitive, or individualistic. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 16, 4654. Maker, C.J., & Nielson, A.B. (1995). Teaching models in the education of the gifted (3rd ed.). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. Merton, R.K. (1968). The Matthew effect in science. Science, 159, 5663. Merton, R.K. (1973). The sociology of science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Mittag, W., & Hager, W. (2000). Ein Rahmenkonzept zur Evaluation psychologischer Interventionsmanahmen [A framework for the evaluation of psychological interventions]. In W. Hager, J.L. Patry, & H. Brezing (Eds.), Handbuch Evaluation psychologischer Interventionsmanahmen [Handbook of evaluating psychological interventions] (pp. 102128). Bern: Huber. Neber, H. (1982). Selbstgesteuertes Lernen [Self-regulated learning]. In B. Treiber & F.E. Weinert (Eds.), Lehr-Lern-Forschung [Teaching-learning research] (pp. 89112). Mnchen: Urban & Schwarzenberg. Neber, H. (1994). Entwicklung und Erprobung einer Skala fr Prferenzen zum kooperativen und kompetitiven Lernen [Development and implementation of a scale for preferences in cooperative and competitive learning]. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht, 41, 282290. Neber, H. (2001a). Begabtenfrderung. Begrndungen, Ziele, Richtungen [Promotion of gifted students: Arguments, purposes, directions]. In Schsisches Landesgymnasium St. Afra (Ed.), Sichtweisen [Perspectives] (pp. 5071). Meissen: Meissner Druckhaus. Neber, H. (2001b). Entdeckendes Lernen [Learning by discovery]. In D.H. Rost (Ed.), Handwrterbuch Pdagogische Psychologie [Dictionary of educational psychology] (pp. 8286). Weinheim: Beltz-PVU. Neber, H., & Heller, K.A. (1995). Untersuchungen zur Nomination von Teilnehmern fr die Deutsche Schler-Akademie [Studies in the nomination of participants of the German Pupils Academy]. Research report. Munich: Institute of Psychological Assessment and Evaluation, University of Munich. Neber, H., & Heller, K.A. (1996a). Auswirkungen der Deutschen Schler-Akademie auf Schule und Studium [Effects of the German Pupils Academy on school and studies]. Research report.

Munich: Institute of Psychological Assessment and Evaluation, University of Munich. Neber, H., & Heller, K.A. (1996b). Identifikation begabter Gymnasialschler durch Lehrer [Identification of gifted highschool students by teachers]. In E. Witruk & G. Friedrich (Eds.), Pdagogische Psychologie im Streit um ein neues Selbstverstndnis [Educational psychology in arguing about a new idendity] (pp. 452459). Landau: Verlag fr Empirische Pdagogik. Neber, H., & Schommer-Aikins, M. (2002). Self-regulated science learning with highly gifted students: The role of cognitive, motivational, epistemological, and environmental variables. High Ability Studies, 13, 5974. Neber, H., Finsterwald, M., & Urban, N. (2001). Cooperative learning with gifted and high-achieving students: A review and meta-analysis of 12 studies. High Ability Studies, 12, 199213. OECD (2001). The OECD program for international student assessment (PISA). (http://www.pisa.oecd.org). Olszewski-Kubilius, P. (1989). Development of academic talent: The role of summer schools. In J. L. VanTassel-Baska & P. Olszewski-Kubilius (Eds.), Patterns of influence on gifted learners (pp. 214230). New York: Teachers College Press. Persson, R.S., Joswig, H., & Balogh, L. (2000). Gifted education in Europe: Programs, practices, and current research. In K.A. Heller, F.J. Mnks, R.J. Sternberg, & R.F. Subotnik (Eds.), International handbook of giftedness and talent (2nd ed., pp. 703733). Amsterdam: Elsevier. Pintrich, P.R., & De Groot, E. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 3340. Pintrich, P.R., & Schrauben, B. (1992). Students motivational beliefs and their cognitive engagement in classroom academic tasks. In D.H. Schunk & J. Meece (Eds.), Student perceptions in the classroom (pp. 149183). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Renzulli, J.S. (2000). The definition of high-end learning. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut. (http://www.sp.uconnnn.edu/ ~nrcgt/sem/semart10.html). Robinson, H.B. (1983). A case for radical acceleration: Programs of the Johns Hopkins University. In C.P. Benbow & J. Stanley (Eds.), Academic precocity: Aspects of its development (pp. 139159). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Rossi, P.H., & Freeman, H.E. (1993). Evaluation. A systematic approach. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Scheirer, M.A. (1994). Process evaluation. In J.S. Wholey, H.P. Hatry, & K.E. Newcomer (Eds.), Handbook of practical program evaluation (pp. 4068). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Schunk, D.H. (1992). Theory and research on students perceptions in the classroom. In D.H. Schunk & J.L. Meece (Eds.), Students perceptions in the classroom (pp. 323). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Scriven, M. (1981). Summative teacher evaluation. In J. Millman (Ed.), Handbook of teacher evaluation (pp. 244271). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Sechrest, L., & Figuerdo, A.J. (1993). Program evaluation. Annual Review of Psychology, 44, 645674. Stufflebeam, D. (1983). The CIPP model for program evaluation. In G.F. Madaus, M. Scriven, & D. Stufflebeam (Eds.), EvaluEJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

228

H. Neber & K.A. Heller: Evaluation of a Summer-School Program

ation models: Viewpoints on educational and human services education (pp. 117142). Boston, MA: Kluwer. Weiner, B. (1984). Principles for a theory of students motivation and their application within an attributional framework. Research on Motivation in Education, 1, 1538. Weiner, B., Frieze, I.H., Kukla, A., Reed, L., Rest, S., & Rosenbaum, R.M. (1971). Perceiving the causes of success and failure. New York: General Learning Press. Winner, E. (1997). Exceptionally high intelligence and schooling. American Psychologist, 52, 10701081. Zimmerman, B.J., & Martinez Pons, M. (1986). Development of a structured interview for assessing student use of self-regulated learning strategies. American Educational Research Journal, 23, 614628. Zimmerman, B.J., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Perceptions of efficacy and strategy use in the self-regulation of learning. In D.H. Schunk & J.L. Meece (Eds.), Student perceptions of the classroom (pp. 185207). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Prof. Dr. Heinz Neber Prof. em. Dr. Kurt A. Heller University of Munich (LMU) Department of Psycholigy Leopoldstr. 13 D-80802 Mnchen Germany Tel. +49 89 2180-9791 Fax +49 89 2180-5250 E-mail neber@edupsy.uni-muenchen.de heller@edupsy.uni-muenchen.de

EJPA 18 (3), 2002 Hogrefe & Huber Publishers

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Executive Branch Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesExecutive Branch Lesson Planapi-247347559Pas encore d'évaluation

- IPCRF 2018 For Teacher I III Final 1Document12 pagesIPCRF 2018 For Teacher I III Final 1Jay BayladoPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 8: Lesson PlanningDocument6 pagesModule 8: Lesson PlanningAlicia M.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ivy DLP 2nd Quart CotDocument4 pagesIvy DLP 2nd Quart CotJhim CaasiPas encore d'évaluation

- BSED-SCIENCE3B GROUP VI ppt.7Document11 pagesBSED-SCIENCE3B GROUP VI ppt.7Novy SalvadorPas encore d'évaluation

- Ed Tpa 1 2022 MathDocument10 pagesEd Tpa 1 2022 Mathapi-589146946Pas encore d'évaluation

- Book - of - IQ - Tests v1Document123 pagesBook - of - IQ - Tests v1xula100% (7)

- Standard 5 Artifact ReflectionDocument3 pagesStandard 5 Artifact Reflectionapi-248589512Pas encore d'évaluation

- DLL - Araling Panlipunan-9 (Sept 26-30)Document3 pagesDLL - Araling Panlipunan-9 (Sept 26-30)G-one Paisones100% (4)

- KAHOOT - Assignment 7.1 FinalDocument4 pagesKAHOOT - Assignment 7.1 FinalJan ZimmermannPas encore d'évaluation

- SW 4020Document2 pagesSW 4020api-282881075Pas encore d'évaluation

- My Eastle TestDocument1 pageMy Eastle Testapi-452990157Pas encore d'évaluation

- Produce Ladies Trousers (TR) : III.3Analysis (10 Minutes)Document2 pagesProduce Ladies Trousers (TR) : III.3Analysis (10 Minutes)Rosean ValditoPas encore d'évaluation

- Design Thinking Intro - The Wallet ProjectDocument14 pagesDesign Thinking Intro - The Wallet Projectapi-251111724100% (1)

- tws-4 PP Presentation Final Copy JM & CMDocument21 pagestws-4 PP Presentation Final Copy JM & CMapi-289910399Pas encore d'évaluation

- fs3 Episode 3 DoneDocument4 pagesfs3 Episode 3 Doneapi-30769713485% (13)

- Jounal Table 2 Edfd461Document3 pagesJounal Table 2 Edfd461api-400657071Pas encore d'évaluation

- Math Lesson Plans for Grades 1-2Document3 pagesMath Lesson Plans for Grades 1-2Michael Teves JamisPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan Speaking ExpressionsDocument2 pagesLesson Plan Speaking ExpressionsMiguel0% (1)

- Magno Assessing Self Regulated LearningDocument41 pagesMagno Assessing Self Regulated LearningCarlo Magno100% (2)

- Griffin Sessions Cover Letter Payson HighDocument1 pageGriffin Sessions Cover Letter Payson Highapi-448278020Pas encore d'évaluation

- Evaluation Sheet (Teaching Practice) : Max. Score Scores Secured Observation of Lessons Average Score 1 2 3 4 5Document2 pagesEvaluation Sheet (Teaching Practice) : Max. Score Scores Secured Observation of Lessons Average Score 1 2 3 4 5Neelofur Ibran AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Episode 10 Designing The Classroom BulletinDocument5 pagesEpisode 10 Designing The Classroom BulletinGerryStarosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Maintain Tools Equipment ParaphernaliaDocument6 pagesMaintain Tools Equipment ParaphernaliaNaddy RetxedPas encore d'évaluation

- As Unit 1 Drama Assessment BookletDocument6 pagesAs Unit 1 Drama Assessment Bookletapi-200177496Pas encore d'évaluation

- Students Perception On STEM EducationDocument9 pagesStudents Perception On STEM EducationSanjana SinhaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in English Vi (Third Grading) : Prepared By: JOBY ANN G. ALONTODocument4 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan in English Vi (Third Grading) : Prepared By: JOBY ANN G. ALONTOZerreitug Elppa50% (2)

- Subtraction Strategies That Lead To RegroupingDocument6 pagesSubtraction Strategies That Lead To Regroupingapi-171857844100% (1)

- Community Helpers Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesCommunity Helpers Lesson Planapi-484650638Pas encore d'évaluation

- IPCRFDocument22 pagesIPCRFSheryl Cruz EspirituPas encore d'évaluation