Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Holistic Decision Making

Transféré par

Celestine ProphecyDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Holistic Decision Making

Transféré par

Celestine ProphecyDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Holistic Decision Making

INTRODUCTION WHAT DOES HOLISM MEAN

The term holism was introduced by the South African statesman Jan Smuts in his 1926 book, Holism and Evolution. Smuts defined holism as "The tendency in nature to form wholes that are greater than the sum of the parts through creative evolution".

WHAT IS DECISION MAKING

Decision-making is an indispensable component of management process and a managers life is filled with making decisions. Decision-making is the process of choosing a course of action from among alternatives to achieve a desired goal. It consists of activities a manager performs to arrive at a conclusion. Managers take decision-making as their control job because they constantly choose what is to be done, which is to do, when to do, where to do and how to do WHAT IS HOLISTIC DECISION MAKING "Holistic decision-making encourages us to be aware of our actions and their impact on the whole Holistic Approach for Decision-making It means everything is inter-related. Decisions taken in one department would affect other department as well. Managers should keep in mind the entire organisations while taking any decision because his decision would affect the interest of stakeholders of the business. In other words, managers should make decisions keeping in view various interest groups such as workers, customers, suppliers etc. Those decisions should be taken that do not harm the interest of any group, be it society, workers, customers or management. The holistic approach is based on the principles of unity or non-duality. Under the principle of unity, the universe is an undivided whole where every particle is connected with

another particle. Rational versus Holistic When complicated decisions have to be made, whether about salaries, layoffs or growth strategy, executives often rely on their underlying values to help them sort through possible options. Profit maximization and rationality form the basis of one such set of values, one frequently used by executives when making these decisions. "By making things quantifiable and rational, executives can have more confidence in their decisions, even when they create uncomfortable outcomes," explains Nathan Washburn, a management researcher at the W. P. Carey School of Business. "But when it comes to working for these executives, that way of thinking might turn their employees off." That unsettled feeling about the calculated nature of rational decisionmaking, with its emphasis on profits as guiding principle, inspired Washburn to launch a study about rational decision-making. Despite being the dominant management value set today, could rational decision-making actually harbor faults? And, could a less widely accepted, but more forward-thinking, "holistic" approach to management decision-making turn out to be more effective?

IMPORTANCE OF HOLISTIC DECISION MAKING Every single minute of human history is marked by decisions that affect every aspect of life, often far from the site of the decision itself. Collectively, these decisions have brought us to where we are today: to an environment marked by economic unpredictability, social instability and environmental degradation

In general, decisions tend to be overly-focused on the achievement of a single aim or the discovery of a solution to an immediate problem. We generally do not include the broader goals that we have for our organization, and too often, we do not consider the wider social, economic and environmental considerations on which our actions will have an impact. In business, a decision made by a manager is generally considered effective if it solves a given problem; but in todays environment, decisions often have a variety of other consequences -- desired or not -- which can attenuate or enhance the quality of the initial decision. This is why modern managerial decision making requires a holistic approach.

Holistic decision making encourages us to be aware of our actions and their impact on the whole; it ensures that we take responsibility and accept accountability for the decisions we make and empowers us to be part of the ongoing process of change. In order to provide managers with the necessary tools to manage modern organizations with a view to building long-term sustainable competitive advantage, it is imperative that organizations embrace a more holistic approach to problem solving. BENEFITS 1. Effectiveness The first impact dimension of a decision is the extent to which it solves the immediate problem that it was meant to solve. As this can be difficult to measure in complex situations, we are more concerned with the ex ante emphasis on problem solving -- the extent to which a manager takes a particular action, which he believes will be sufficient to solve the immediate problem. We call this the executive dimension of a decision. 2. Operative Learning As a result of having interacted to solve a particular problem, the agents involved have the capacity to learn something. The second impact dimension of a decision is the extent to which it enhances or diminishes the capacity of the two agents, both individually and as a team, to solve similar problems in the future. We refer to this dimension as the operational learning dimension. 3. Relational Learning Each interaction that a manager has with a stakeholder is an opportunity for the two agents to learn about each other, and the decision taken by the manager and its subsequent implementation will influence the extent to which the two agents will want to work with each other in the future. The third impact dimension of a decision is the extent to which the agents involved in it increase their willingness to work together in the future as a result of having interacted on the decision. We refer to this dimension as the relational learning dimension.

To illustrate the holistic decision-making framework, we will focus on the simplest possible relationship between a focal decision maker, whom we refer to as the Active Agent (AA), and a stakeholder, internal or external to the firm, whom we refer to as the Reactive Agent (RA). As depicted in Figure One, the Active Agent (AA) faces a problem, such as falling margins due to erosion in prices. To solve it, he decides to initiate an action (A) so that someone else, whom we will call the Reactive Agent (RA), will initiate a reaction (R), so that together, the action and the reaction can solve the problem. The RA in this case might be a subordinate, who is asked to investigate the causes for the price erosion, or a supplier, who is asked to absorb a reduction in prices. In either case, the AA relies on the reaction of the RA for the decision to take its course. The action and the reaction represent the executive dimension of the decision. If the problem is solved, then the decision and the subsequent action are considered effective; otherwise they are not. In our example, the submission of a report by the subordinate (RA) that allows the AA to arrest the falling margins would lead to the original decision of involving the subordinate being qualified as good. Similarly, a proposal by the manager (AA) to the supplier (RA) for a price reduction would also be considered a good outcome if the latter accepts the proposal. Clearly, the manager (AA) can involve stakeholders in different ways to solve problems. Let us take the case of the subordinate (RA). The manager could either instruct his subordinate to impose a price reduction on the supplier (directive problem solving), or ask him to investigate the reasons behind the falling margins and propose a solution (open ended problem solving). In the first case, the manager might be successful in arresting the decline in margins, but would have enhanced his subordinate's ability to solve a similar problem in the future only marginally, if at all. In the second case, the subordinate might after the appropriate analysis come up with a solution that does indeed require a price reduction from the supplier, or he might come up with a completely different solution. Whatever solution he comes up with, he would have partaken actively in generating it. The manager might require him to explain his solution, and to improve it by taking additional factors into consideration that might have been overlooked. Clearly, in the second case, the manager-subordinate interaction is very different from the first one, because there is greater probability that both the manager and the subordinate will learn from the experience of having worked together to solve the problem of margin erosion. They might even learn about each other's strengths and weaknesses. For example, the manager might learn that the subordinate is highly data driven, and that he

complements the manager's big picture approach. Our point is that by taking into account the operative learning dimension, managers can improve the long-term performance of their firms. The executive and operative learning dimensions are illustrated in Figure One and Figure Two. Figure One: The Executive Dimension: Focusing Only on Effectiveness

Figure 2: The Strategic Dimension: Focusing on Operational Learning and Effectiveness

In the above example of the problem of falling margins, the manager might decide that the solution lies in asking a supplier to reduce prices. Again, there are multiple ways in which this can be achieved. The use of power to force a price reduction might resolve the immediate problem, but it would affect the willingness of the supplier to continue to work with the manager and his firm. The manager must therefore ask himself - Is it fair to ask this supplier to reduce prices? Can we offer something in return -- such as higher purchasing quantities per order or higher annual volumes that might partly offset the impact of the price reduction?

Unfortunately, in the majority of cases, decisions are made based only on dimension #1 (how effective they will be in solving a particular problem), without attention paid in any systematic way to the other two critical dimensions. Figure Three: The Leadership Dimension: Focusing on Effectiveness, Operational Learning and Relational Learning

Ohio State Universitys Paul Nutt profiled 78 case studies of managerial decision making and found that most decision processes were solution centered, which, in his words, seemed to restrict innovation, limit the number of alternatives considered, and perpetuate the use of questionable tactics. According to Nutt, The bias for action causes [managers] to limit their search, consider too few alternatives, and pay too little attention to people who are affected, not realizing that decisions fail for just these reasons. Managers want to find out what is wrong and fix it quickly, and the all-too-frequent result is a hasty problem definition that proves to be misleading. Stanfords James March and Nobel Laureate Herbert Simon have also identified this problem and described the common motivation to use bland alternatives, stating that perceived time pressure begins to mount as decision-making reaches the idea stage, often creating artificial pressure to adopt the first workable idea that is uncovered.

As defined earlier, the executive dimension of a decision maker is her capacity to solve problems and execute her immediate plans flawlessly. Though such a capacity is basically positive, it can lead to failures if the two other dimensions are not considered. Nutt confirmed this through his studies: When the direction set by a manager rapidly narrows, or displaces a solution, little learning can occur; and When managers impose an answer, they create a misleading clarity that sweeps aside important sources of ambiguity and uncertainty. In this context it becomes clear that a possible exchange with the relevant stakeholder might have led to a better decision than the immediate focus on the problems solution. As a result, Nutt found that virtually half of the decisions in organizations fail. His study of 356 decisions in medium-to-large organizations in the U.S. and Canada revealed that these failures can be traced to managers who impose solutions, limit the search for alternatives, and use power to implement their plans. In a recent article, he pointed out that decision makers typically seek to act swiftly, whereas only one in ten decisions actually requires urgent action, and only one in a hundred necessitates crisis management. In closing We have identified three dimensions that every manager must take into account during decision deliberation. By considering the two learning dimensions of our decision making framework in addition to the commonlyconsidered effectiveness dimension, a firm can increase its capability-and knowledge-building competencies and promote stakeholder cohesion. It is important to note that a holistic approach does not by any means provide easy answers. If anything, it highlights the fact that decisions are fraught with complexity. For this reason, we view decision making as a managerial competence that requires deep knowledge of specific products, markets and industries; finely honed skills in managing interpersonal relationships, effective communications, and negotiations; and the right attitude based on professionalism, integrity, and a genuine interest in the development of all stakeholders.

Holistic Decision Making

Our thesis has clear implications for managers on the one hand, and for management educators on the other. Most importantly, it constitutes advice for managers on how to manage their stakeholder relationships. By taking the three decision-impact dimensions into account, managers can immediately begin to enhance the quality of their decision making. And educators can also begin to integrate stakeholder issues into their curriculum by encouraging students to focus on the operative and relational learning dimensions of their decisions.

Read more: http://forbesindia.com/article/rotman/holistic-decisionmaking/12822/0#ixzz1kOco4HO9

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Activity Design ScoutingDocument10 pagesActivity Design ScoutingHoneyjo Nette100% (9)

- Geo Lab Report Point LoadDocument9 pagesGeo Lab Report Point Loaddrbrainsol50% (2)

- HappinessDocument1 pageHappinessSciJournerPas encore d'évaluation

- How to Use TA to Communicate EffectivelyDocument6 pagesHow to Use TA to Communicate EffectivelyItaPas encore d'évaluation

- Personal TransformationDocument320 pagesPersonal TransformationChidambaram100% (1)

- ATP Draw TutorialDocument55 pagesATP Draw TutorialMuhammad Majid Altaf100% (3)

- Psychological Capital PresentationDocument8 pagesPsychological Capital PresentationSyed Baqar AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Attitudes - ObDocument75 pagesAttitudes - Ob3091 Sahil GanganiPas encore d'évaluation

- Personal Development: (Articles)Document20 pagesPersonal Development: (Articles)Jay Ann Salisod100% (2)

- Chapter 4 - Emotions and MoodsDocument10 pagesChapter 4 - Emotions and MoodsOrveleen de los SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Manage Yourself and Lead OthersDocument10 pagesManage Yourself and Lead OthersAhmad AlMowaffakPas encore d'évaluation

- Stay PositiveDocument4 pagesStay PositiveSaira Zafar100% (1)

- Anger ManagementDocument27 pagesAnger ManagementVishnu MenonPas encore d'évaluation

- Concepts of StressDocument9 pagesConcepts of Stressdexter100% (4)

- Stress Management Techniques for Students and ProfessionalsDocument6 pagesStress Management Techniques for Students and ProfessionalsMuhammad Tariq SadiqPas encore d'évaluation

- Personal MasteryDocument3 pagesPersonal MasteryMelchor Padilla DiosoPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning Styles and StudyingDocument50 pagesLearning Styles and StudyingmikePas encore d'évaluation

- Workshop One - Work-Life BalanceDocument3 pagesWorkshop One - Work-Life Balanceapi-319898057Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mice ReviewerDocument50 pagesMice ReviewerChin Chin GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Leatham Management PlanDocument2 pagesLeatham Management Planapi-264716980Pas encore d'évaluation

- Secular Vs Spiritual ValuesDocument13 pagesSecular Vs Spiritual Valuesaditya_b32Pas encore d'évaluation

- Shagun Verma Attitude & Job SatisfactionDocument56 pagesShagun Verma Attitude & Job SatisfactionShagun VermaPas encore d'évaluation

- Applied Psychology in HRDocument2 pagesApplied Psychology in HRDebayan DasguptaPas encore d'évaluation

- STRESS MANAGEMENT PROGRAM - Seminar MaterialsDocument6 pagesSTRESS MANAGEMENT PROGRAM - Seminar MaterialsAlvin P. ManuguidPas encore d'évaluation

- MB0038 PDFDocument347 pagesMB0038 PDFsaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Self Esteem and EffectivenessDocument4 pagesSelf Esteem and EffectivenessNupur PharaskhanewalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Advantages and Qualities of EntrepreneurshipDocument7 pagesAdvantages and Qualities of EntrepreneurshipChandra RaviPas encore d'évaluation

- Psycho-Sexual Stages of DevelopmentDocument12 pagesPsycho-Sexual Stages of DevelopmentEmmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Mapping Human Emotions Shows Strong Mind Body Connection - The Mind UnleashedDocument6 pagesResearch Mapping Human Emotions Shows Strong Mind Body Connection - The Mind UnleashedsarmasarmatejaPas encore d'évaluation

- Factors Contributing To The Emotional IntelligenceDocument15 pagesFactors Contributing To The Emotional Intelligenceshashank100% (1)

- Dr. J.I. Nwapi,: MBBS, Fwacp, FMCFM Lecturer I/Consultant Family PhysicianDocument46 pagesDr. J.I. Nwapi,: MBBS, Fwacp, FMCFM Lecturer I/Consultant Family PhysicianjaphetnwapiPas encore d'évaluation

- What If Money Was EasyDocument11 pagesWhat If Money Was EasyFurtuna Mirela CristinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Get It Right, Make It TightDocument182 pagesGet It Right, Make It Tightflownow888Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3Document33 pagesChapter 3Grigoras Elena DianaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Skill of Self Confidence by Dr. Ivan JosephDocument6 pagesThe Skill of Self Confidence by Dr. Ivan JosephThori Truong100% (1)

- Emotional Intelligence Test: Report For: Varughese Thomas Completion: January 19, 2019Document17 pagesEmotional Intelligence Test: Report For: Varughese Thomas Completion: January 19, 2019Shibu Thomas100% (1)

- Coping Skills AnxietyDocument2 pagesCoping Skills AnxietyMissi GreggPas encore d'évaluation

- Work Life IntegrationDocument10 pagesWork Life IntegrationKrutika AshtikarPas encore d'évaluation

- UHV MergedDocument212 pagesUHV MergedYash KadamPas encore d'évaluation

- Emotional Intelligence PresentationDocument31 pagesEmotional Intelligence Presentationsweety100% (1)

- How EQ enhances performance beyond IQDocument7 pagesHow EQ enhances performance beyond IQSahil SethiPas encore d'évaluation

- Emotional IntelligenceDocument10 pagesEmotional IntelligenceSapna PremchandaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Entrep Module 4Document23 pagesEntrep Module 4Dryxlyn Myrns Ortega100% (1)

- Motivation Theories: BehaviorDocument4 pagesMotivation Theories: BehaviorMurtaza EjazPas encore d'évaluation

- Amity University, Mumbai Aibas: Title: Learned Optimism ScaleDocument9 pagesAmity University, Mumbai Aibas: Title: Learned Optimism Scalekaashvi dubeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Functions of AttitudeDocument10 pagesFunctions of AttitudeMohammed Yunus100% (3)

- 06 Emotions and MoodsDocument29 pages06 Emotions and MoodsMonaIbrheemPas encore d'évaluation

- Forgive and Be HealedDocument57 pagesForgive and Be HealedBillBen C RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Discover Your Design PersonalityDocument8 pagesDiscover Your Design PersonalitysafiaoreoPas encore d'évaluation

- Individual Behavior FactorsDocument33 pagesIndividual Behavior FactorsAnchal mandhir100% (1)

- Emotion Management GroupDocument12 pagesEmotion Management Groupapi-384358306Pas encore d'évaluation

- Entrepreneurship Vs Self-EmploymentDocument23 pagesEntrepreneurship Vs Self-EmploymentClinton NyachieoPas encore d'évaluation

- Role of Ethics in Organizational BehaviourDocument16 pagesRole of Ethics in Organizational BehaviourJ LAL0% (1)

- Perception and Individual Decision MakingDocument27 pagesPerception and Individual Decision MakingAyesha KhatibPas encore d'évaluation

- Organizational Behavior: Stephen P. RobbinsDocument41 pagesOrganizational Behavior: Stephen P. RobbinsVidhya SrinivasPas encore d'évaluation

- Human To Human Relationship TheoryDocument1 pageHuman To Human Relationship TheorySunshine Mae AumPas encore d'évaluation

- 15 Lessons From Best Selling Books to Help You SucceedDocument3 pages15 Lessons From Best Selling Books to Help You SucceedfunnyouPas encore d'évaluation

- How Your Brain Fights Happiness and the Positive Actions You Can TakeDocument8 pagesHow Your Brain Fights Happiness and the Positive Actions You Can Takeantony garces100% (1)

- The Basic Laws of Life - The Spiritual Law of ATTRACTIONDocument5 pagesThe Basic Laws of Life - The Spiritual Law of ATTRACTIONNathaniel BernardPas encore d'évaluation

- Manifesting Your Best Future Self: Building Adaptive ResilienceD'EverandManifesting Your Best Future Self: Building Adaptive ResiliencePas encore d'évaluation

- Outthink Your Trauma: Mindfully managing your thoughtsD'EverandOutthink Your Trauma: Mindfully managing your thoughtsPas encore d'évaluation

- Confidence Unleashed: The Key to Unlocking Your Potential and Achieving Your GoalsD'EverandConfidence Unleashed: The Key to Unlocking Your Potential and Achieving Your GoalsPas encore d'évaluation

- BhopalDocument4 pagesBhopalCelestine ProphecyPas encore d'évaluation

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument6 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentCelestine ProphecyPas encore d'évaluation

- A Man Asked GODDocument1 pageA Man Asked GODCelestine ProphecyPas encore d'évaluation

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument4 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentCelestine ProphecyPas encore d'évaluation

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument3 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentCelestine ProphecyPas encore d'évaluation

- Charny - Mathematical Models of Bioheat TransferDocument137 pagesCharny - Mathematical Models of Bioheat TransferMadalena PanPas encore d'évaluation

- SYS600 - Visual SCIL Application DesignDocument144 pagesSYS600 - Visual SCIL Application DesignDang JinlongPas encore d'évaluation

- Páginas Desdeingles - Sep2008Document1 pagePáginas Desdeingles - Sep2008anayourteacher100% (1)

- Laser Plasma Accelerators PDFDocument12 pagesLaser Plasma Accelerators PDFAjit UpadhyayPas encore d'évaluation

- From The Light, On God's Wings 2016-14-01, Asana Mahatari, JJKDocument26 pagesFrom The Light, On God's Wings 2016-14-01, Asana Mahatari, JJKPaulina G. LoftusPas encore d'évaluation

- Dasha TransitDocument43 pagesDasha Transitvishwanath100% (2)

- Writing and Presenting A Project Proposal To AcademicsDocument87 pagesWriting and Presenting A Project Proposal To AcademicsAllyPas encore d'évaluation

- Navid DDLDocument7 pagesNavid DDLVaibhav KarambePas encore d'évaluation

- Bluehill BrochureDocument24 pagesBluehill BrochureGeorge SingerPas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Oil Corporation- Leading Indian State-Owned Oil and Gas CompanyDocument10 pagesIndian Oil Corporation- Leading Indian State-Owned Oil and Gas CompanyPrakhar ShuklaPas encore d'évaluation

- Db2 Compatibility PDFDocument23 pagesDb2 Compatibility PDFMuhammed Abdul QaderPas encore d'évaluation

- Garden Silk Mills Ltd.Document115 pagesGarden Silk Mills Ltd.jkpatel221Pas encore d'évaluation

- Risk Assessment For Modification of Phase 1 Existing Building GPR TankDocument15 pagesRisk Assessment For Modification of Phase 1 Existing Building GPR TankAnandu Ashokan100% (1)

- PLC 2 Ladder DiagramDocument53 pagesPLC 2 Ladder DiagramAnkur GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- CH13 QuestionsDocument4 pagesCH13 QuestionsAngel Itachi MinjarezPas encore d'évaluation

- NX569J User ManualDocument61 pagesNX569J User ManualHenry Orozco EscobarPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Prepare Squash Specimen Samples For Microscopic ObservationDocument3 pagesHow To Prepare Squash Specimen Samples For Microscopic ObservationSAMMYPas encore d'évaluation

- Plato Aristotle Virtue Theory HappinessDocument17 pagesPlato Aristotle Virtue Theory HappinessMohd SyakirPas encore d'évaluation

- CV Raman's Discovery of the Raman EffectDocument10 pagesCV Raman's Discovery of the Raman EffectjaarthiPas encore d'évaluation

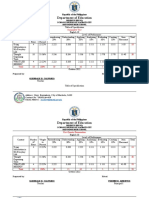

- Table of Specification ENGLISHDocument2 pagesTable of Specification ENGLISHDonn Abel Aguilar IsturisPas encore d'évaluation

- The History of American School Libraries: Presented By: Jacob Noodwang, Mary Othic and Noelle NightingaleDocument21 pagesThe History of American School Libraries: Presented By: Jacob Noodwang, Mary Othic and Noelle Nightingaleapi-166902455Pas encore d'évaluation

- IS BIOCLIMATIC ARCHITECTURE A NEW STYLE OF DESIGNDocument5 pagesIS BIOCLIMATIC ARCHITECTURE A NEW STYLE OF DESIGNJorge DávilaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 John Timm Final Narrative WeeblyDocument8 pages2016 John Timm Final Narrative Weeblyapi-312582463Pas encore d'évaluation

- HistoryDocument45 pagesHistoryRay Joshua Angcan BalingkitPas encore d'évaluation

- Circle Midpoint Algorithm - Modified As Cartesian CoordinatesDocument10 pagesCircle Midpoint Algorithm - Modified As Cartesian Coordinateskamar100% (1)

- Balkan TribesDocument3 pagesBalkan TribesCANELO_PIANOPas encore d'évaluation

- Carnot CycleDocument3 pagesCarnot CyclealexontingPas encore d'évaluation