Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Bringing Organisation Change - A Framework: About

Transféré par

Sri RamDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Bringing Organisation Change - A Framework: About

Transféré par

Sri RamDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Volume 13 Number 6 1989

BRINGING

ABOUT

ORGANISATION CHANGE A FRAMEWORK

by Wolverhampton J. D. Stewart Business School, Wolverhampton Polytechnic

Introduction his article is concerned with describing two theoretical models and their practical application in bringing about organisation change. The relevance of the subject is taken as given since there is an abundance of literature both on reasons for organisations to consider changing themselves; e.g. 1992 [1]; and on methods/strategies/ techniques to utilise [2]. The models discussed here really amount to an overall framework within which the various methods and strategies can be utilised. The purpose of this is to provide a set of guidelines that will help determine which particular method or strategy is likely to be effective in differing circumstances. The content of the article will be most relevant to readers who are responsible for advising or deciding on planned change. In that sense the framework is only applicable in circumstances where a conscious decision has been taken to bring about some desired change. The framework rests on a number of key propositions. These are discussed in the next section.

The Propositions There are three propositions which need to be accepted if the framework is to have any validity. The first is simply this: change even at the level of the organisation, has to be observable or measurable to have any meaning. Organisations may consciously decide to change any of a whole range of their features. An indicative list could include the following: Size Performance Structure Information and control systems Markets Management style Culture

The suggestion that any one of those features could be changed in isolation is in itself debatable given what is known from systems theory. However, it is more often the case in practice that organisations do intend to change one feature in the belief that everything else

31

JOURNAL OF EUROPEAN INDUSTRIAL TRAINING

can and will stay the same. What is important is that the difference between the pre- and post-change situations can be observed or measured. Without the condition, planned organisation change is simply inconceivable. The implication of this is that organisation change is concerned with organisation behaviour. Some items from the indicative list are easier to observe or measure than others; e.g. size as opposed to management style, performance as opposed to culture. It remains the case, however, that a change in any of the features will produce a change in the way the organisation behaves [3]. It is behaviour which can be observed or measured. Having established that organisation change is about behaviour we can move onto the second and related proposition. It is this: organisation change requires individual change. This may seem an obvious statement but it is a factor which is often overlooked. A change in organisation behaviour cannot be achieved unless some or all of the individuals within the organisation change the way they behave. How can performance, management style, or culture change in an organisation unless people behave differently?

evidence of readers' own experience will be enough to support that point! The need for individual behaviour change leads us to the final proposition. Individual behaviour change requires two conditions to be met. (a) Learning has to occur. (b) Motivation to apply the learning has to exist. Individual behaviour is partly a function of ability; i.e. what a person is able to do; and willingness; i.e. what a person wishes to do [5]. It is quite possible that individuals fail to behave as desired not because they are unwilling but because they are unable. Equally, it may be the case that they have the ability but are unwilling to apply it in practice. What is clear is that both conditions need to be met. It is worth noting here that the meaning attached to learning in this proposition is to do with acquisition of knowledge, skills and abilities. Debate about the wider role of learning in influencing or determining behaviour, including sources of motivation, will be left to psychologists. These then are the three propositions which underpin the rest of this article. A simple case has been made out to support each of them. If they appear unsound then what follows will be invalid. If, however, the propositions are accepted, the models and consequent framework will be useful in informing strategies for bringing about organisation change. The Models The first of two models is taken from a paper written by Hinings [6]. It suggests two critical variables which will affect the likely success of any planned change effort. These are the degree to which those affected accept there is a need for change; i.e. agree there is a problem; and secondly accept the appropriateness of the change being suggested or imposed, i.e. agree with the solution. These two variables can be combined in a simple matrix as in Figure 1 below. This matrix serves two useful purposes. First, it allows for an initial assessment of the potential success of any organisation change. Research can be carried out in the organisation to establish the current degree of agreement and acceptance which can be used either as a basis for decisions on what change to implement or to assess how much effort is likely to be needed to make a given change

QUITE POSSIBLE THAT INDIVIDUALS FAIL TO BEHAVE AS DESIRED NOT BECAUSE THEY ARE UNWILLING BUT BECAUSE THEY ARE UNABLE

32

The obvious objections to this point will arise from the features of size and structure. It is possible to argue that an expansion or contraction in size will not require individuals to behave differently. The reality is that it will if the change in size is to work and succeed in practice. The size of an organisation is a critical factor influencing how people relate with each other and changes in size will require changes in the behaviour of individuals and their relationships [4]. Organisation structure is a more common example where this second proposition is ignored. Changes in structure are often imposed without attention being paid to the required behaviour changes of individuals. The result is that the new structure does not work in practice, i.e. it does not bring about the desired or expected change in organisation behaviour. The anecdotal

Volume 13 Number 6 1989

Figure 1. Critical Variables Affecting Success of Organisation Change

Acceptance of problem

Agree

Disagree

Acceptance of solution

Agree

High success

Moderate success

Disagree

Low success

Lowest success

successful. Secondly the matrix identifies the conditions that need to exist or be created for organisation change to be successful. These are that those affected agree with both the definition of the problem and the proposed solution. Only under those conditions are they likely to change their individual behaviour. The question that arises from this last point is how to shift the people affected from the bottom left or right of the matrix to the top left quadrant? Our second model can help to answer that question. This second model was devised by the author to conceptualise the contribution of training and development to bringing about change in organisations. There are two key elements in the model. The first is a continuum of behaviour change from minor to major as perceived by individuals affected. The second is a conceptual continuum of training and development. These two elements

are seen to be related and are combined as in Figure 2 below. A few words of explanation are necessary before examining the utility and application of the model. The distinction between training and development is meant to illustrate two important points. First, that HRD interventions to support organisation change are likely to be those associated with personal development at the major behaviour change end of the change continuum, and to the more traditional, training activities at the minor end. Second, while most if not all HRD interventions are concerned with all three elements of knowledge, skills and attitudes, the emphasis is likely to be different at different levels of change as indicated in the model. Some examples may be useful to illustrate the use of the change continuum. Since it is important to classify behaviour change

33

JOURNAL OF EUROPEAN INDUSTRIAL TRAINING

according to the perception of those affected, the following examples can only be considered as indicative generalisations. Outcome of Performance Appraisal may lead to a requirement for a slight change in behaviour and the person affected needs only the knowledge of this requirement, e.g. performance targets. New Boss/Colleagues is likely to mean individuals need to behave differently but again only need the knowledge of in what ways. Reorganisation/Restructuring of the whole organisation or single department will lead to new ways of behaving in the job which may require additional job related knowledge and skills and, perhaps, attitudes. New Job arising from major reorganisations, is closer to a major behaviour change requiring new knowledge, skills and attitudes on the part of those affected. New, Significant Organisation Policies will require significant changes in the kinds of behaviour which "to a large extent are influenced by personal values and attitudes; e.g. adoption of an equal opportunities policy usually implies major behavioural change. Fundamental Organisational Change such as experienced by privatised public corporations or organisations moving from a production to marketing orientation will require almost a new paradigm of work to be adopted by individuals and related to major behavioural change. Application and Use The two models have several useful applications in the practice of organisation change. The first model usefully illustrates the truism that individuals will be more committed to change if they accept that the need exists

and agree that the proposed new behaviours will be beneficial. It also implicitly supports the notion that individual involvement in change processes is necessary for those conditions to exist. The second model should remind those responsible for bringing about change of the need to provide training and development. It also indicates what kind of HRD interventions will be required. This helps to ensure the first condition of the third proposition identified earlier is met.

MAJOR BEHAVIOUR CHANGE IS LIKELY TO MEET MORE RESISTANCE AND GREATER EFFORT TO OVERCOME IT

Combining and using two models together suggest general principles which can help meet the second condition, i.e. motivation to apply. Minor behaviour change is likely to be associated with low resistance, and strategies to build agreement, i.e. shift those affected to the top left quadrant in Figure 1; will probably need to concentrate on knowledge acquisition through information sharing and communication. Conversely, major behaviour change is likely to meet more resistance and require greater effort to overcome it. Most theories of motivation, whether content or process theories [5], would support the notion that such change is likely to need greater participation and involvement. The normative re-educative approach to bringing about change also focuses on individual involvement in identifying the problem and devising the solution where personal beliefs and values need to be revised [7]. This analysis of the two models provides the basis of the framework for deciding on strategies for bringing about organisation change. This is represented in Figure 3. The framework suggests that methods which emphasise communication will be

34

Volume 13 Number 6

1989

appropriate and effective for minor behaviour change while those which emphasise genuine involvement are likely to be more effective for major behaviour change. This classification helps to indicate the utility of competing strategies, methods and techniques. We can illustrate the use of the framework with two hypothetical examples, one drawn from commerce and one from the public sector. A large high street retailer plans to introduce its own credit card. The purpose is to encourage customer loyalty and to promote extra sales. This will obviously have implications for sales staff and give rise to training needs. However, the required behaviour change could be either simply accepting a different form of payment or actively seeking to persuade customers to apply for and use the new facility. The first possibility is classified as a minor behaviour change while the second is much closer to a major behaviour change. Strategies to implement the change in staff behaviour, including the nature of training and development interventions, need to be different in each case.

approach. In these cases adjustments to selection, payment, and reward systems may be required. Training and development methods such as problem identification meetings, team development, action learning, self and peer assessment, etc. all of which enable genuine involvement in the identification of the problem and selection of solutions; will be more effective than formal information sessions in influencing the adoption of required new behaviours. Summary and Conclusion The framework is really a representation of a commonsense approach to bringing about change. Given that individuals have the ability to do so, there are only three reasons why they do not behave as organisations wish them to. First, they do not know; i.e. they are not aware of the desired behaviour. Second, they do not believe; i.e. they are aware of required behaviour but do not believe the organisation and its management seriously desire it. Third, they do not agree with it; i.e. they are aware of both the desired behaviour and the high importance attached to it by the organisation and management, but the behaviour is inconsistent with their own personal views, beliefs or values. The message is simple for those responsible for bringing about organisation change. To be successful, the change has to be known, believed and agreed with by those affected. Change strategies adopted need to be capable of creating those conditions if the change itself is to be effective.

TO BE SUCCESSFUL, THE CHANGE HAS TO BE KNOWN, BELIEVED AND AGREED WITH

The second example concerns a local council which wishes to reorganise a department now subject to competitive tendering. Some staff will only be affected by the introduction of new administrative systems; a change which is classified as minor in the framework. Others, especially operational staff and their managers at all levels, will be required to develop a commercial orientation to their work in order to compete with private sector companies. Such a change is so fundamental as to be classified as major in the framework. Strategies will again need to be different in each case to bring about successful change. In both examples the minor behaviour change is likely to be achieved through written materials, changes in operating manuals and short formal training sessions to explain, demonstrate and give practice in new procedures. The major behavioural changes, however, will not be achieved by the same

References 1. Underwood, R., "1992: New Frontiers, New Horizons", Personnel Management, IPM, March 1989. 2. For example see Peters, J. (Ed.), Action for Change: The Politics of Implementation, MCB University Press, 1987. 3. Lee, R. and Lawrence, P., Organisation Behaviour, Hutchinson, 1985. 4. For a general discussion of this see Argyle, M., Social Psychology of Work, Allen Lane, 1972. 5. Ribeaux, P. and Poppleton, S., Psychology and Work, Macmillan, 1978. 6. Hinings, R., "Planning, Organising and Managing Change", Local Government Training Board, 1983. 7. Bennis, W.G., Benne, K.D., Chin, R., Corey, K.E. (Eds.), The Planning of Change, Holt, Reinhart and Winston, 1976.

35

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Managing Change: The Process and Impact on PeopleD'EverandManaging Change: The Process and Impact on PeopleÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- Managing in An Environment of Continuous ChangeDocument8 pagesManaging in An Environment of Continuous ChangeMohammad Raihanul HasanPas encore d'évaluation

- Change Management PaperDocument16 pagesChange Management PaperEko SuwardiyantoPas encore d'évaluation

- Managing Change RectifiedDocument3 pagesManaging Change RectifiedAzka IhsanPas encore d'évaluation

- SID#: 1031425/1 Module: Organizational Behavior: Edition P 662)Document10 pagesSID#: 1031425/1 Module: Organizational Behavior: Edition P 662)Karen KaveriPas encore d'évaluation

- Change Management 2010Document5 pagesChange Management 2010Mrinal MehtaPas encore d'évaluation

- Change ManaementDocument16 pagesChange ManaementMuhammad ImranPas encore d'évaluation

- MGT and Leadership, Intake 20 Gikondo UNIT 3Document21 pagesMGT and Leadership, Intake 20 Gikondo UNIT 3emelyseuwasePas encore d'évaluation

- Solved Subjective Questions For Final ExamsDocument14 pagesSolved Subjective Questions For Final Examsmishal iqbalPas encore d'évaluation

- Leadership CH 3-5 SlideDocument20 pagesLeadership CH 3-5 SlideMndaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study 1 - Change ManagementDocument5 pagesCase Study 1 - Change ManagementHimanshu TiwariPas encore d'évaluation

- Organizational ChangeDocument12 pagesOrganizational ChangeRohit KaliaPas encore d'évaluation

- OD and Change AssignmentDocument16 pagesOD and Change AssignmentUsmanPas encore d'évaluation

- MGMT 625 Midterm SubjectivesDocument7 pagesMGMT 625 Midterm SubjectivesJawad HaleemPas encore d'évaluation

- GSGM7324 Organisational Development and Change ManagementDocument12 pagesGSGM7324 Organisational Development and Change ManagementJohthiNadia Nadason NadasonPas encore d'évaluation

- Introductiontoorganizationalchange 140128013519 Phpapp01 PDFDocument50 pagesIntroductiontoorganizationalchange 140128013519 Phpapp01 PDFMansi KothariPas encore d'évaluation

- Change Is Inevitable. Growth Is Optional.Document32 pagesChange Is Inevitable. Growth Is Optional.chanishaPas encore d'évaluation

- BHR 331assignment Organisatinal Development 201800617Document8 pagesBHR 331assignment Organisatinal Development 201800617Parks WillizePas encore d'évaluation

- Change ManagementDocument22 pagesChange ManagementSimit KhajanchiPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment InnovationDocument5 pagesAssignment InnovationbaljitminhasPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 15 SummaryDocument11 pagesChapter 15 SummaryGil Hernandez-ArranzPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Module 6Document13 pagesFinal Module 6Suraj ReddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Change Management: Muhammad HashimDocument11 pagesChange Management: Muhammad HashimMalkeet SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- LIYA TADESSE Change Management AssignmentDocument10 pagesLIYA TADESSE Change Management Assignmentአረጋዊ ሐይለማርያምPas encore d'évaluation

- Orginizational Change Management PDFDocument9 pagesOrginizational Change Management PDFLillian KahiuPas encore d'évaluation

- Pugh UnderstandingDocument12 pagesPugh Understandinggonytitan9Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment TwoDocument16 pagesAssignment TwoRiyaad MandisaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mu0018 B1807 SLM Unit 01 PDFDocument24 pagesMu0018 B1807 SLM Unit 01 PDFpankajatongcPas encore d'évaluation

- Organizational Change: Organizational Change - A Process in Which A Large Company orDocument15 pagesOrganizational Change: Organizational Change - A Process in Which A Large Company orerielle mejico100% (2)

- Organizational Context Process Change Organization Effectiveness Turnaround Progress Character Configuration StructureDocument11 pagesOrganizational Context Process Change Organization Effectiveness Turnaround Progress Character Configuration StructuregprasadatvuPas encore d'évaluation

- Change Management & Work Teams: Submitted To: Mam Khizra AhmadDocument16 pagesChange Management & Work Teams: Submitted To: Mam Khizra AhmadSohaib AnjumPas encore d'évaluation

- Change Management Best Practice GuideDocument23 pagesChange Management Best Practice GuideVictor Hugo Saavedra Gonzalez100% (2)

- Strategic Change Process: SyllabusDocument32 pagesStrategic Change Process: Syllabussamreen workPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Analysis of Models OF Organizational Development: (For Internal Assessment)Document25 pagesCritical Analysis of Models OF Organizational Development: (For Internal Assessment)All in SylvesterPas encore d'évaluation

- Organizational Development - Chapter 9Document13 pagesOrganizational Development - Chapter 9Nelvin VallesPas encore d'évaluation

- Foundation of Organization DevelopmentDocument20 pagesFoundation of Organization Developmentrohankshah1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Implementatiolsssdfgbhn AlexDocument16 pagesImplementatiolsssdfgbhn AlexAlex StanescuPas encore d'évaluation

- Change Management - Chapter Review Question AnswersDocument3 pagesChange Management - Chapter Review Question AnswersRashminPas encore d'évaluation

- Management & Organizational DevelopmentDocument13 pagesManagement & Organizational DevelopmentRaman Sharma100% (2)

- Literature Review of Resistance To ChangeDocument5 pagesLiterature Review of Resistance To Changefhanorbnd100% (1)

- THE NATURE OF PLANNED CHANGE-DoreenDocument27 pagesTHE NATURE OF PLANNED CHANGE-DoreenTusingwire DoreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Change ManagementDocument12 pagesChange Managementupendrak2035Pas encore d'évaluation

- Content of ResearchDocument10 pagesContent of ResearchYousef QuriedPas encore d'évaluation

- Organizational ChangeDocument20 pagesOrganizational Changeshubham singhPas encore d'évaluation

- Module-1 Cm&odDocument130 pagesModule-1 Cm&odkhushbookayasth100% (2)

- Introduction To Organizational ChangeDocument47 pagesIntroduction To Organizational ChangemonikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Change Management Best Practice GuideDocument21 pagesChange Management Best Practice GuideShiva Prasad100% (1)

- Definition: Organisational Change Is The Process by Which Organisations Move From Their PresentDocument6 pagesDefinition: Organisational Change Is The Process by Which Organisations Move From Their PresentMonica KharePas encore d'évaluation

- Module 1 - Org DevelopmentDocument2 pagesModule 1 - Org DevelopmentAzael May PenaroyoPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 1 Chapter Two The Nature of Planned Change 20230929 165955 0000Document28 pagesGroup 1 Chapter Two The Nature of Planned Change 20230929 165955 0000saitamak317Pas encore d'évaluation

- Leading Change and Innovation: Date: 2 OCTOBER 2020Document16 pagesLeading Change and Innovation: Date: 2 OCTOBER 2020Umair MansoorPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review WP1 Final Version 07102007Document60 pagesLiterature Review WP1 Final Version 07102007Mostafa OmarPas encore d'évaluation

- Change Management 101: A PrimerDocument11 pagesChange Management 101: A Primerh00ver0Pas encore d'évaluation

- Organisational BehaviourDocument12 pagesOrganisational Behaviourabhi malikPas encore d'évaluation

- Leading ChangeDocument93 pagesLeading ChangeChaudhary Ekansh PatelPas encore d'évaluation

- Schnetzer - Sayed, Mostafa Abdelmoneim Omar - Digital StrategizingDocument12 pagesSchnetzer - Sayed, Mostafa Abdelmoneim Omar - Digital StrategizingMostafa OmarPas encore d'évaluation

- Change ManagementDocument11 pagesChange ManagementSamyak Raj100% (1)

- Change Management For Managers: The No Waffle Guide To Managing Change In The WorkplaceD'EverandChange Management For Managers: The No Waffle Guide To Managing Change In The WorkplaceÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (6)

- Gonzalez SanmamedDocument14 pagesGonzalez SanmamedGuadalupe TenagliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Personal Development: High School Department Culminating Performance TaskDocument3 pagesPersonal Development: High School Department Culminating Performance TaskLLYSTER VON CLYDE SUMODEBILAPas encore d'évaluation

- Editorial Board 2023 International Journal of PharmaceuticsDocument1 pageEditorial Board 2023 International Journal of PharmaceuticsAndrade GuiPas encore d'évaluation

- Pinpdf Com 91 Colour Prediction Trick 91 ClubDocument3 pagesPinpdf Com 91 Colour Prediction Trick 91 Clubsaimkhan8871340% (1)

- Pdhpe Term 1 KindergratenDocument26 pagesPdhpe Term 1 Kindergratenapi-249015874Pas encore d'évaluation

- Second Final Draft of Dissertation (Repaired)Document217 pagesSecond Final Draft of Dissertation (Repaired)jessica coronelPas encore d'évaluation

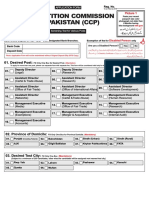

- Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) : S T NS T NDocument4 pagesCompetition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) : S T NS T NMuhammad TuriPas encore d'évaluation

- GA Classic Qualification SpecificationDocument10 pagesGA Classic Qualification SpecificationThomasPas encore d'évaluation

- Textile Conservation in Museums: Learning ObjectivesDocument12 pagesTextile Conservation in Museums: Learning ObjectivesdhhfdkhPas encore d'évaluation

- Skripsi Lutfi Alawiyah 2017Document126 pagesSkripsi Lutfi Alawiyah 2017Adryan TundaPas encore d'évaluation

- RIZAL Summary Chapter 1-5Document10 pagesRIZAL Summary Chapter 1-5Jemnerey Cortez-Balisado CoPas encore d'évaluation

- MTB Mle Week 1 Day3Document4 pagesMTB Mle Week 1 Day3Annie Rose Bondad MendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 5 Curriculum ImplementationDocument38 pagesModule 5 Curriculum ImplementationRen Ren100% (5)

- 10 Global Trends in ICT and EducationDocument3 pages10 Global Trends in ICT and Educationmel m. ortiz0% (1)

- N.E. Essay Titles - 1603194822Document3 pagesN.E. Essay Titles - 1603194822კობაPas encore d'évaluation

- Organisational Behaviour PDFDocument129 pagesOrganisational Behaviour PDFHemant GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Stem Whitepaper Developing Academic VocabDocument8 pagesStem Whitepaper Developing Academic VocabKainat BatoolPas encore d'évaluation

- DR Cheryl Richardsons Curricumlum Vitae-ResumeDocument4 pagesDR Cheryl Richardsons Curricumlum Vitae-Resumeapi-119767244Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Clue 1:: Teacher's GuideDocument183 pagesReading Clue 1:: Teacher's GuideQuốc Nam LêPas encore d'évaluation

- Isnt It IronicDocument132 pagesIsnt It IronicNiels Uni DamPas encore d'évaluation

- Summer Internship Completion Certificate FormatDocument1 pageSummer Internship Completion Certificate FormatNavneet Gupta75% (12)

- ICT Curriculum For Lower Secondary 2Document40 pagesICT Curriculum For Lower Secondary 2Basiima OgenzePas encore d'évaluation

- Unit II An Annotated OutlineDocument2 pagesUnit II An Annotated Outlineapi-420082848Pas encore d'évaluation

- Resume Format: Melbourne Careers CentreDocument2 pagesResume Format: Melbourne Careers CentredangermanPas encore d'évaluation

- Card Format Homeroom Guidance Learners Devt AssessmentDocument9 pagesCard Format Homeroom Guidance Learners Devt AssessmentKeesha Athena Villamil - CabrerosPas encore d'évaluation

- Law School Academic Calendar S Y 2017-2018 First Semester: June 5, 2017 - October 6, 2017Document25 pagesLaw School Academic Calendar S Y 2017-2018 First Semester: June 5, 2017 - October 6, 2017nvmndPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan-Primary 20 MinsDocument5 pagesLesson Plan-Primary 20 Minsapi-2946278220% (1)

- Rup VolvoDocument22 pagesRup Volvoisabelita55100% (1)

- Ldla CV 01-13-19Document7 pagesLdla CV 01-13-19api-284788195Pas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence Law Reading ListDocument9 pagesEvidence Law Reading ListaronyuPas encore d'évaluation