Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Gender Factor in Audit Quality Evidence From Nigeria

Transféré par

Alexander DeckerCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Gender Factor in Audit Quality Evidence From Nigeria

Transféré par

Alexander DeckerDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) Vol 3, No 4, 2012

www.iiste.org

Gender Factor in Audit Quality: Evidence from Nigeria

C.O. Mgbame, F.I.O. Izedonmi, A. Enofe Department of Accounting, Faculty of Management Sciences, University of Benin, Nigeria Abstract The stimulant for researches on auditor specific characteristic has its base largely on evidence from psychological researches on the existence of certain gender-based differences amongst individuals. Thus Psychological research on gender differences has also ignited research interest in auditing. Therefore the objective of the study was to investigate if auditor gender also signaled differentials in the risk profile and problem solving abilities; two important traits with potential of influencing the auditor judgment and audit quality. Primary data was employed for the study using a sample of 150 auditors and the z-score statistical test. The findings suggested gender differences afterall may become a possible explanatory factor in assessing audit quality. However, considerable caution is suggested with regards to policy implications as there may be the need to control for more contextual factors. Keywords: Audit quality, Gender, Auditor judgement INTRODUCTION Financial reporting plays a critical role in maintaining intricate balance between management and ownership; it stands as a core process in the continuum of other allied management functions needed to facilitate business and economic decisions by stakeholders. It follows that the information credibility of financial reports is of utmost importance to stakeholders. In this regards, the audit function plays a crucial role in maintaining systematic confidence in the integrity of financial reporting the same way audits add credibility to corporate financial reports. Consequently, studies have noted that audits add credibility to the financial information by providing an independent verification of management-provided financial reports, thus reducing investors information risk (Fairchild, 2007; Coate, Florence and Kral, 2002). The Audit quality therefore, is a basic ingredient in enhancing the credibility of the organization to users of accounting information and this is because financial reporting credibility is partly reflected in the confidence of users in audited financial reports. The value relevance of auditing depends upon the quality of audits. However, Moizer (1997) noted that the appraisal of the indices of measuring the quality of the audit service is not without its challenges since audit quality is typically unobservable (Barton 2005; Francis 2004). Thus, according to Hay and Knechel (2010), auditing could be categorized as a type of credence good and hence auditors add credibility to corporate financial reports by expressing an opinion about the true and fair representation but only in so far as the users of financial statements perceive that opinion as valuable. That is, the audit service acquires value because of the trust clients place upon the auditor (Houghton and Jubb 2005). In this regards, Hardies, Breesh and Branson (2010) argued that audit quality is not simply a linear function of auditor competence and auditor independence, but also on the markets perception about the value of the auditors report which is the result of the perceived competence and the perceived independence of the auditor. Seen from this perspective, audit quality refers in this case to credibility of the audit opinion which is a measurement for the degree of confidence users place upon the information provided by the auditor. Auditors come with varying degrees of characteristics such as gender, educational level, age, religion, experiences etc. However, the focus of this study is on the impact of auditor gender on Audit quality. DeFond and Francis (2005), in providing a theoretical basis for research on gender differences affecting audit quality notes that since auditing is to a large extent a matter of professional judgment, it is plausible that audit quality may be mediated or moderated by a variety of characteristics of the individual auditor. Consequently, there has been research efforts aimed at examining the tendency for audit credibility beyond the analysis of the audit firm characteristics to individual auditors and precisely that certain characteristics are associated with auditor gender such as problem-solving ability (Bierstaker and Wright, 2001; Libby and Tan, 1992), technical expertise (Tan and Kao, 1999), risk profile (Amerongen, 2007), experience (Early, 2002; Shelton, 1999), and independence (DeAngelo, 1981).

81

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) Vol 3, No 4, 2012

www.iiste.org

It suffices to note that Hardies, Breesch and Branson (2010) drew attention to the simultaneous usage of gender and sex in most auditing researches and suggested the need for necessary clarifications to be made. As submitted by Deaux (1985) and Eagly (1994), differences arising from social, cultural and psychological frames between men and women may be analyzed as gender differences while Sex should be used in reference to differentiation on the basis of the demographic categories. Gender should be used in reference to judgments or inferences about the nature of femaleness and maleness, of masculinity and femininity (Deaux 1985; Eagly 1994). Consequently, the researcher adopts the views of Deaux (1985) and Eagly (1994) as appropriate for the study. STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM What this study considers ambiguous in the auditor gender and audit quality relationship which has subsequently formed the stimuli for the research work is based on two conflicting theoretical underpinnings. Firstly, there seems to be a growing body of empirical auditing literature based on psychological studies that provides evidence that certain characteristics are associated with auditor gender such as problem-solving ability (Bierstaker and Wright, 2001; Libby and Tan, 1992), technical expertise (Tan and Kao, 1999), and risk profile (Amerongen, 2007). Even if an alternative opinion is considered, based on the maleness of the auditing profession (Hardies et al., 2010), accounting and auditing are still strongly gender-typed in favour of men in our society (Carnegie and Napier 2010; Dwyer and Roberts 2004; White and White 2006). It seems reasonable to conjecture that, on average, female auditors may be perceived as less competent than male auditors (Gold, Hunton and Gomaa, 2009). There is also a growing argument that in some corners that by nature, female auditors tends to be more thorough and attentive to details and could be more trusted and honest. This may provide validation for the effects of gender in the context of auditing and auditing research. On the contrary, theres also a theoretical basis as projected in the occupational socialization theory that differences tend to disappear as employees are socialized within the work environment. Smith and Rogers (2000) argued in this regards, that the same may also hold for those working in the accounting profession. Consequently, this study finds these theoretical underpinnings on the intervening role of auditor gender on audit quality as demanding more incisive analysis across different settings. Furthermore, several studies have examined the relationship between company specific and audit firm specific factors in Nigeria that could mediate audit quality, the researcher is unaware of any study that examined the implications of auditor specific factors such as gender on audit quality. Hence the study attempts to analyze the significance of the interactive effects of auditor gender on audit quality using a study sample from Nigeria. OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY The following objectives have been specified to guide the direction of the study. 1. To examine if psychological research on gender differences can be a valid basis for auditing research. 2. To examine if Auditor gender is an intervening variable in determining audit quality. HYPOTHESIS OF THE STUDY The stimulant for researches on auditor specific characteristic has its base largely on evidence from psychological researches (Peterson, 2001; Sherman, Buddie, Dragan, End and Finney 1999) on the existence of certain gender- based differences amongst individuals. Though arguments exist (Bussey and Bandura, 1999) to counter the opinion that the differences observed could be more of culturally or socially induced stereotypes and thus is uncorrelated to sex. This implies that certain traits have been assigned to auditor being feminine or masculine. The finding by Ittonen and Peni (2009) gives support to the idea that an auditor gender may be systematically associated with audit quality. The rationale is that theoretical expectations may not necessarily be unified given the opposing psychological and context dependent perspectives. The implication is that findings from the general population may not be easily interpolated to the specific context of auditors as it may not be too distant from conjectural opinions. Consequently, we state the following hypothesis H1: Psychological research on gender differences cannot be a valid basis for auditing research. H2: Auditor gender is not an intervening variable in determining audit quality. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY The research methodology is based on that of Hardies, Breesch and Branson (2009) using Primary data retrieved from a sample size of 105 staffs of audit firms. The study area was Edo, Delta and Lagos states in Nigeria in order to have a cross-sectional base. The research instrument adopted was that of Hardies, Breesch and Branson

82

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) Vol 3, No 4, 2012

www.iiste.org

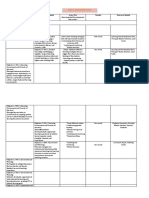

(2009) in a similar study with some modifications made to reflect the study area. The research instrument was composed of generic (i.e. non-audit related) questions. The usage of such generic questions results from the fact that they have been widely used in psychological research on gender differences. Hence, our research instrument is well-suited to examine if psychological research can serve as a valid foundation for hypotheses about (and explanations for) gender differences among auditors. The study employed Z-test in estimating the data. PRESENTATION AND ANALYSIS OF RESULT INSERT TABLE 1 The table above shows descriptive analysis of the difference in problem-solving abilities of male and female auditors. The problem-solving score is derived from the number of correct answers on the ten questions regarding problem-solving. The minimum score of males is 2 while that of females is 0, while the maximum score of males is 8 while that of females is 9. On average, the average performance of males in problem solving ability of males was about 5.36 with a standard deviation of 1.97 while the average performance of females in problem solving ability of males was about 4.55 with a standard deviation of 2.74. The Z-statistics of -2.99 with a p-value of 0.003 indicates that there exists a significant difference in the problem solving abilities between male and female auditors. As seen from the table on average male auditors has better problem-solving skills than female auditors which may imply that male auditors discover more potential misstatements than female auditors. This finding agrees with the findings of (Dar-Nimrod and Heine, 2006, Bierstaker and Wright, 2001; Libby and Tan, 1992). Males are therefore more than females stimulated to further develop their mathematical abilities, resulting in a vicious stimulus-response-cycle. And also consistent with the findings of Penner and Paret, (2008) which found men, on average, to be somewhat better mathematical problem-solvers than women. Implicit in the findings as argued by Anandarajan, Kleinman and Palmon (2008) is that since the understanding of financial statement and audit reports is most likely to be influenced by mathematical abilities, males may tend to deliver better audits. Consequently, we fail to accept the hypothesis (H1) that Psychological research on gender differences cannot be a valid basis for auditing research. INSERT TABLE 2 The table above shows descriptive analysis of the difference in the risk aversion of male and female auditors. The risk aversion score is derived from the rating of the likelihood of engaging in specific risk activities. The minimum risk score of males is 18 while that of females is 13, while the maximum risk score of males is 35 while that of females is 33. On average, the average score of males in risk aversion was about 25.75 with a standard deviation of 5.65 while the average score of females in risk aversion was about 20.91 with a standard deviation of 7.01. The Z-statistics of -5.64 with a p-value of 0.000 indicates that there exists a significant difference in the risk aversion between male and female auditors. As seen from the table on average female auditors are more risk averse than male auditors which may imply that risk taking is perceived as a masculine attribute. This is consistent with the findings of Barsky et al., 1997; Byrnes et al., 1999; Damodaran, 2008; Jianakoplos and Bernasek, 1998) which found evidence that women, in general, are more risk-averse than men. The study finding also agrees with Beckmann and Menkhoff (2008), Hardies, Breesch and Branson (2009). Thus as female auditors tend to be more risk-averse, there is the allusion that female auditors may set a lower materiality threshold and select larger samples than male auditors which could result in a higher number of material misstatements detected and reported by female auditors than by male auditors. Consequently, we fail to accept the hypothesis (H2) that Auditor gender is not an intervening variable in determining audit quality. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION Auditing in practice is largely a judgment and decision-making process, ultimately audit quality is dependent upon the auditors judgment and decision-making qualities. The quality of an auditors judgment which may be specified in terms of discovery and reporting of material misstatements depends in turn on certain auditor characteristics such as problem solving ability, risk profile, and independence from the client. Based on psychological literature, very recently some researchers (e.g. Gold et al., 2009) have posited that there are gender differences in personal auditor

83

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) Vol 3, No 4, 2012

www.iiste.org

characteristics (e.g. risk aversion), leading to gender-differentiated audit judgments and decisions. However, such assertions may not directly justify the existence of aprori expectation in that regard as alternative views about the smoothing effects of context on such gender differences as employees are socialized within the work environment have also been argued. The study examined particularly, if gender differences also signaled differences in risk profile and problem solving abilities; two important traits with potential of influencing the auditor judgment and audit quality. The findings suggested that sex differences afterall may become a possible explanatory factor in assessing audit quality. However, considerable caution is suggested with regards to inference of causality and the associated policy implications as there is the need for further research in this area which is largely inadequate in Nigeria. Though the finding may have implications for audit team compositions, it is recommended that a broader scale of auditor characteristics may also need to also be examined while more specific organizational or work place factors may also need to be controlled for. References Amerongen, C. M. (2007) Auditors Performance in Risk and Control Judgments: An Empirical Study. Ph. D. dissertation, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Anandarajan, A., Kleinman, G. and Palmon, D. (2008) Novice and expert judgment in the presence of going concern uncertainty: The influence of heuristic biases and other relevant factors, Psychological Review, 106(4), pp. 676712. Barton, J. (2005): Who Cares about Auditor Reputation? Contemporary Accounting Research 22 (3): 549586. Barber, B. M. and Odean, T. (2001) Boys Will be Boys: Gender, Overconfidence, and Common Stock Investment, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), pp. 261292. Baron-Cohen, S. (2004) The Essential Difference. Male and Female Brains and the Truth About Autism (New York: Basic Books). Baron-Cohen, S. and Wheelwright, S. (2004) The Empathy Quotient: An Investigation of Adults with Asperger Syndrome or High Functioning Autism, and Normal Sex Differences, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(2), pp. 163175. Barsky, R. B., Juster, F. T., Kimball, M. S. and Shapiro, M. D. (1997) Preference Parameters and Behavioral Heterogeneity: An Experimental Approach in the Health and Retirement Survey, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(2), pp. 537580. Bnardi, J. and M. Arnold (1999): Expertise in Auditing, Auditing - a Journal of Practice and Theory, 12(supplement), pp. 2145. Bierstaker, J. L. and Wright, S. (2001) A Research Note Concerning Practical Problem-Solving Ability as a Predictor of Performance in Auditing Tasks, Behavioral Research in Accounting, 13, pp. 4962. Boyer, T. W. and Byrnes, J. P. (2009) Adolescent risk-taking: Integrating personal, cognitive, and social aspects of judgment, Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(1), pp. 2333. Breesch, D. and Branson, J. (2009) The Effects of Auditor Gender on Audit Quality, The IUP Journal of Accounting Research & Audit Practices, 8(3/4), pp. 78107. Bussey, K. and Bandura, A. (1999) Social Cognitive Theory of Gender Development and Byrnes, J. P., Miller, D. C. and Schafer, W. D. (1999) Gender Differences in Risk Taking: A Meta-Analysis, Psychological Bulletin, 125(3), pp. 367383. Carnegie, G. D., & Napier, C. J. (2010) Traditional accountants and business professionals: Portraying the accounting profession after Enron. Accounting, Organizations and Society. Coate, C. J, R. Florence, and K.L. Kral (2002): Financial Statement Audits, a Game of Chicken? Journal of Business Ethics 41, 1 11. Ceci, S. J., Williams, W. M. and Barnett, S. M. (2009) Womens Underrepresentation in Science: Chapman, E., Baron-Cohen, S., Auyeung, B., Knickmeyer, R., Taylor, K. and Hackett, G. (2006) Fetal Testosterone and Empathy: Evidence from the Empathy Quotient (EQ) and the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test, Social Neuroscience, 1(2), pp. 135148. Chin, C. and Chi, H. (2008) Sex Matters: Gender Differences in Audit Quality. Working paper presented at the 2008 Annual Meeting of the American Accounting Association, August 36, Anaheim. Chung, J. and Monroe, G. (1998) Gender Differences in Information Processing: An Empirical Test of the Hypothesis-Confirming Strategy in an Audit Context, Accounting & Finance, 38(2), pp. 265279.

84

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) Vol 3, No 4, 2012

www.iiste.org

Chung, J. and Monroe, G. (2001) A Research Note on the Effects of Gender and Task Complexity on an Audit Judgment, Behavioral Research in Accounting, 13, pp. 111126. Cohen, J. (1990) Things I Have Learned (So Far), American Psychologist, 45(12), pp. 13041312. Cohen, J. and T. Kida. 1989. The impact of analytical review results, internal control reliability, and experience on auditors use of analytical review. Journal of Accounting Research (Autumn): 263-76. Costa, P. T. Jr., Terracciano, A. and McCrae, R. R. (2001) Gender Differences in Personality Traits Across Cultures: Robust and Surprising Findings, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(2), pp. 322331. Damodaran, A. (2008) Strategic Risk Taking. A Framework for Risk Management (New Jersey: Pearson Education). DeAngelo, L. E. (1981) Auditor Independence, low balling, and disclosure regulation, Journal of Accounting and Economics, 3(2), pp. 113127. Deaux, K. and Major, B. (1987) Putting gender into context: An interactive model of gender-related behavior, Psychological Review, 94(3), pp. 369389. Dwyer, P. D., & Roberts, R. W. (2004): The contemporary gender agenda of the US public accounting profession: embracing feminism or maintaining empire? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 15(1), 159177. Early, C. E. (2002) The Differential Use of Information by Experienced and Novice Auditors in the Performance of Ill-Structured Audit Tasks, Contemporary Accounting Research, 19(4), pp. 595614. Eckel, C. C. and Grossman, P. J. (2002) Sex Differences and Statistical Stereotyping in Attitudes Toward Financial Risk, Evolution and Human Behavior, 23(4), pp. 281295. Eynon, G., Hill, N. T. and Stevens, K. T. (1997) Factors that Influence the Moral Reasoning Abilities of Accountants: Implications for Universities and the Profession, Journal of Business Ethics, Fairchild, R. (2008): Does Audit tenure lead to more fraud? A game theoretic approach. Retrieved from http// papers.ssrn.com on 2nd January 2011. Feingold, A. (1994) Gender Differences in Personality: A Meta-Analysis, Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 429456. Francis, J. R. (2004) What Do We Know About Audit Quality? British Accounting Review, 36(4), pp. 345368. Gold, A., Hunton, J. E. and Gomaa, M. (2009) The Impact of Client and Auditor Gender on Auditors Judgments, Accounting Horizons, 23(1), pp. 118. Graham, J. F. (2002) Gender Differences in Investment Strategies: An Information Processing Perspective, International Journal of Bank Marketing, 20(1), pp. 1726. Hardies, K., Breesch, D. and Branson, J. (2009) Male and Female Auditors: Who in this Land is the Fairest of All? Accountancy & Bedrijfskunde, 29(7), pp. 2230. Hyde, J. S. and Linn, M. C. (2006) Gender Similarities in Mathematics and Science, Science, 314(5799), pp. 599600. Ittonen, K. and Peni, E. (2009) Auditors Gender and Audit Fees. Working paper presented at the 32nd Annual Congress of the European Accounting Association, May 1215, Tampere. Jianakoplos, N. A. and Bernasek, A. (1998) Are Women More Risk Averse? Economic Inquiry, 36(4),pp. 620630. Judd, C. M. and Park, B. (1993) Definition and Assessment of Accuracy in Social Stereotypes, Psychological Review, 100(1), pp. 109128. Kiefer, A. K. and Sekaquaptewa, D. (2007) Implicit stereotypes and womens math performance: How implicit gender-math stereotypes influence womens susceptibility to stereotype threat, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(5), pp. 825832. Hay W. and R. W.Knechel (2010): Behavioral Research in Auditing and Its Impact on Audit Education, Issues in Accounting Education, 15(4), pp. 695712. Hardies, K., Breesch, D., & Branson, J. (2009). Auditor Gender [sic] - A Research Note. Working paper. Retrieved from http// ssrn.com on 21st January,2012. Koonce, L. and Mercer, M. (2005): Using Psychology Theories in Archival Financial Accounting Research, Journal of Accounting Literature, 24, pp. 175214. Krishnan, G. V., and L. M. Parsons. 2006. Getting to the bottom line: An exploration of gender and earnings quality. Working paper. Available at SSRN: Libby, R. and Tan, H. T. (1992) Modeling the Determinants of Audit Expertise, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 19(8), pp. 701716.Managerial Auditing Journal, 23(4/5), pp. 345366. Miller, H. and Bichsel, J. (2004) Anxiety, working memory, gender, and math performance, Personality and

85

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) Vol 3, No 4, 2012

www.iiste.org

Individual Differences, 37(3), pp. 591606. Nettle, D. (2007) Empathizing and Systemizing: What are they, and what do they Contribute to our Understanding of Psychological Sex Differences? British Journal of Psychology, 98(2), pp. 237255. Neidermeyer, P. E., T. L. Tuten, and A. A. Neidermeyer. (2003): Gender differences in auditors attitudes towards lowballing: implications for future practice. Women in Management Review, 18 (8): 406v413. Nonis, S. A., Ford, C. W., Logan, L. and Hudson, G. (1996) College Students Blood Donation Behavior: Relationship to Demographic, Perceived Risk, and Incentives, Health Marketing Quarterly, 13(4), pp. 3346. Nosek, B. A., Banaji, M. R. and Greenwald, A. G. (2002) Math = Male, Me = Female, Therefore Math Me, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(1), pp. 4459. ODonnell, E. and Johnson, E. N. (2001) The Effects of Auditor Gender and Task Complexity on Information Processing Efficiency, International Journal of Auditing, 5(2), pp. 91105. OFallon, M. J. and Butterfield, K. D. (2005) A Review of the Empirical Ethical Decision-Making Literature: 19962003, Journal of Business Ethics, 59(4), pp. 375414. OLaughlin, E. M. and Brubaker, B. S. (1998) Use of landmarks in cognitive mapping: Gender differences in self report versus performance, Personality and Individual Differences, 24(5), pp. 595601. Olsen, R. A. and Cox, C. M. (2001) The Influence of Gender on the Perception and Response to Investment Risk: The Case of Professional Investors, The Journal of Psychology and Financial Markets, 2(1), pp. 2936. Owhoso, V. E., Messier, W. F. Jr., & Lynch, J. G. Jr. (2002). Error Detection by Industry-Specialized Teams during Sequential Audit Review. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(3), 883900. Penner, A. M. and Paret, M. (2008) Gender Differences in Mathematics Achievement: Exploring the Early Grades and the Extremes, Social Science Research, 37(1), pp. 239253. Personality and Social Psychology, 94(1), pp. 168182. Peterson, R. A. (2001): On the Use of College Students in Social Science Research: Insights from a Second-Order Meta-Analysis, Journal of Consumer Research, 28(3), pp. 450461. Ridgeway, C. L. (2009) Framed Before We Know It: How Gender Shapes Social Relations, Gender & Society, 23(2), pp. 145160. Robey, R. R. (2004) Reporting point and interval estimates of effect-size for planned contrasts: fixed within effect analyses of variance, Journal of Fluency Disorders, 29(4), pp. 307341. Rowley, S. J., Kurtz-Costes, B., Mistry, R. and Feagans, L. (2007) Social Status as a Predictor of Race and Gender Stereotypes in Late Childhood and Early Adolescence, Social Development, 16(1), pp. 50168. Schmidt, F. L. (1996) Statistical Significance Testing and Cumulative Knowledge in Psychology: Implications for Training of Researchers, Psychological Methods, 1(2), pp. 115129. Schmidt, W. C. (1997) World-Wide Web Survey Research: Benefits, Potential Problems, and Solutions, Behavior Research Methods Instruments and Computers, 29(2), pp. 274279. Schmitt, D. P., Realo, A., Voracek, M. and Allik, J. (2008) Why Cant a Man Be More Like a Woman? Sex Differences in Big Five Personality Traits Across 55 Cultures, Journal of Schubert, R., Brown, M., Gysler, M. and Brachinger, H. W. (1999) Gender and Economic Shelton, S. W. (1999): The Effect of Experience on the Use of Irrelevant Evidence in Auditor Judgment, The Accounting Review, 74(2), pp. 217-224. Sherman, R. C., Buddie, A. M., Dragan, K. L., End, C. M. and Finney, L. J. (1999): Twenty years of PSPB: Trends in Content, Design, and Analysis, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(2), pp. 177187. Signorella, M. L. and Jamison, W. (1986) Masculinity, Femininity, Androgyny, and Cognitive Performance: A Meta-Analysis, Psychological Bulletin, 100(2), pp. 207228. Tan, H. T. and Kao, A. (1999) Accountability Effects on Auditors Performance: The Influence of Knowledge, Problem-Solving Ability, and Task Complexity, Journal of Accounting Research, 37(1), pp. 209223. Thompson, B. (2007) Effect sizes, confidence intervals, and confidence intervals for effect sizes, Psychology in the Schools, 44(5), pp. 423432. Venezia, C. C. (2008) Are Female Accountants More Ethical Than Male Accountants: A Comparative Study Between The U.S. And Taiwan, International Business & Economics Research Journal, 7(4), pp. 110. Weber, E. U., Blais, A. R. and Betz, N. E. (2002) A Domain-specific Risk-attitude Scale: Measuring Risk Perceptions and Risk Behaviors, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 15(4), pp. 263 290.

86

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) Vol 3, No 4, 2012

www.iiste.org

White, M. J., & White, G. W. (2006). Implicit and Explicit Occupational Gender Stereotypes. Sex Roles, 55(3), 259266. Wilson, M. and Daly, M. (1985) Competitiveness, risk-taking, and violence: The young male syndrome, Ethnology and Sociobiology, 6(1), pp. 5973.

LIST OF TABLES Table 1 Analysis of gender Differences on Problem Solving N MALES 105 Mean 5.3619 Std. Deviation 1.97155 Minimum 2.00 Maximum 8.00 Z -2.99 (0.003)

105 FEMALES Field Survey (2011)

4.5524

2.74906

.00

9.00

Table 2 Analysis of gender differences on Risk Aversion N MALES 105 Mean 25.7524 20.9143 Std. Deviation 5.65648 7.01114 Minimum 18.00 13.00 Maximum 35.00 33.00 Z -5.644(0.000)

FEMALES 105 Field Survey (2011)

87

This academic article was published by The International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE). The IISTE is a pioneer in the Open Access Publishing service based in the U.S. and Europe. The aim of the institute is Accelerating Global Knowledge Sharing. More information about the publisher can be found in the IISTEs homepage: http://www.iiste.org The IISTE is currently hosting more than 30 peer-reviewed academic journals and collaborating with academic institutions around the world. Prospective authors of IISTE journals can find the submission instruction on the following page: http://www.iiste.org/Journals/ The IISTE editorial team promises to the review and publish all the qualified submissions in a fast manner. All the journals articles are available online to the readers all over the world without financial, legal, or technical barriers other than those inseparable from gaining access to the internet itself. Printed version of the journals is also available upon request of readers and authors. IISTE Knowledge Sharing Partners EBSCO, Index Copernicus, Ulrich's Periodicals Directory, JournalTOCS, PKP Open Archives Harvester, Bielefeld Academic Search Engine, Elektronische Zeitschriftenbibliothek EZB, Open J-Gate, OCLC WorldCat, Universe Digtial Library , NewJour, Google Scholar

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Availability, Accessibility and Use of Information Resources and Services Among Information Seekers of Lafia Public Library in Nasarawa StateDocument13 pagesAvailability, Accessibility and Use of Information Resources and Services Among Information Seekers of Lafia Public Library in Nasarawa StateAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of The Practicum Training Program of B.S. Tourism in Selected UniversitiesDocument9 pagesAssessment of The Practicum Training Program of B.S. Tourism in Selected UniversitiesAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Availability and Use of Instructional Materials and FacilitiesDocument8 pagesAvailability and Use of Instructional Materials and FacilitiesAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Concerning Food Safety Among Restaurant Workers in Putrajaya, MalaysiaDocument10 pagesAssessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Concerning Food Safety Among Restaurant Workers in Putrajaya, MalaysiaAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Some Micronutrient (ZN and Cu) Status of Fadama Soils Under Cultivation in Bauchi, NigeriaDocument7 pagesAssessment of Some Micronutrient (ZN and Cu) Status of Fadama Soils Under Cultivation in Bauchi, NigeriaAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Relationships Between Students' Counselling NeedsDocument17 pagesAssessment of Relationships Between Students' Counselling NeedsAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Asymptotic Properties of Bayes Factor in One - Way Repeated Measurements ModelDocument17 pagesAsymptotic Properties of Bayes Factor in One - Way Repeated Measurements ModelAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Housing Conditions For A Developing Urban Slum Using Geospatial AnalysisDocument17 pagesAssessment of Housing Conditions For A Developing Urban Slum Using Geospatial AnalysisAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Barriers To Meeting The Primary Health Care Information NeedsDocument8 pagesBarriers To Meeting The Primary Health Care Information NeedsAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of The Skills Possessed by The Teachers of Metalwork in The Use of Computer Numerically Controlled Machine Tools in Technical Colleges in Oyo StateDocument8 pagesAssessment of The Skills Possessed by The Teachers of Metalwork in The Use of Computer Numerically Controlled Machine Tools in Technical Colleges in Oyo StateAlexander Decker100% (1)

- Assessment of Teachers' and Principals' Opinion On Causes of LowDocument15 pagesAssessment of Teachers' and Principals' Opinion On Causes of LowAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Survivors' Perceptions of Crises and Retrenchments in The Nigeria Banking SectorDocument12 pagesAssessment of Survivors' Perceptions of Crises and Retrenchments in The Nigeria Banking SectorAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Attitude of Muslim Female Students Towards Entrepreneurship - A Study On University Students in BangladeshDocument12 pagesAttitude of Muslim Female Students Towards Entrepreneurship - A Study On University Students in BangladeshAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Productive and Reproductive Performances of CrossDocument5 pagesAssessment of Productive and Reproductive Performances of CrossAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Factors Responsible For Organizational PoliticsDocument7 pagesAssessment of Factors Responsible For Organizational PoliticsAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Are Graduates From The Public Authority For Applied Education and Training in Kuwaiti Meeting Industrial RequirementsDocument10 pagesAre Graduates From The Public Authority For Applied Education and Training in Kuwaiti Meeting Industrial RequirementsAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Application of The Diagnostic Capability of SERVQUAL Model To An Estimation of Service Quality Gaps in Nigeria GSM IndustryDocument14 pagesApplication of The Diagnostic Capability of SERVQUAL Model To An Estimation of Service Quality Gaps in Nigeria GSM IndustryAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Antibiotic Resistance and Molecular CharacterizationDocument12 pagesAntibiotic Resistance and Molecular CharacterizationAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Antioxidant Properties of Phenolic Extracts of African Mistletoes (Loranthus Begwensis L.) From Kolanut and Breadfruit TreesDocument8 pagesAntioxidant Properties of Phenolic Extracts of African Mistletoes (Loranthus Begwensis L.) From Kolanut and Breadfruit TreesAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessing The Effect of Liquidity On Profitability of Commercial Banks in KenyaDocument10 pagesAssessing The Effect of Liquidity On Profitability of Commercial Banks in KenyaAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Applying Multiple Streams Theoretical Framework To College Matriculation Policy Reform For Children of Migrant Workers in ChinaDocument13 pagesApplying Multiple Streams Theoretical Framework To College Matriculation Policy Reform For Children of Migrant Workers in ChinaAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment in Primary School Mathematics Classrooms in NigeriaDocument8 pagesAssessment in Primary School Mathematics Classrooms in NigeriaAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment For The Improvement of Teaching and Learning of Christian Religious Knowledge in Secondary Schools in Awgu Education Zone, Enugu State, NigeriaDocument11 pagesAssessment For The Improvement of Teaching and Learning of Christian Religious Knowledge in Secondary Schools in Awgu Education Zone, Enugu State, NigeriaAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Analyzing The Economic Consequences of An Epidemic Outbreak-Experience From The 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West AfricaDocument9 pagesAnalyzing The Economic Consequences of An Epidemic Outbreak-Experience From The 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West AfricaAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- An Investigation of The Impact of Emotional Intelligence On Job Performance Through The Mediating Effect of Organizational Commitment-An Empirical Study of Banking Sector of PakistanDocument10 pagesAn Investigation of The Impact of Emotional Intelligence On Job Performance Through The Mediating Effect of Organizational Commitment-An Empirical Study of Banking Sector of PakistanAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis The Performance of Life Insurance in Private InsuranceDocument10 pagesAnalysis The Performance of Life Insurance in Private InsuranceAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Application of Panel Data To The Effect of Five (5) World Development Indicators (WDI) On GDP Per Capita of Twenty (20) African Union (AU) Countries (1981-2011)Document10 pagesApplication of Panel Data To The Effect of Five (5) World Development Indicators (WDI) On GDP Per Capita of Twenty (20) African Union (AU) Countries (1981-2011)Alexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of Teachers Motivation On The Overall Performance ofDocument16 pagesAnalysis of Teachers Motivation On The Overall Performance ofAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of Frauds in Banks Nigeria's ExperienceDocument12 pagesAnalysis of Frauds in Banks Nigeria's ExperienceAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Andragogy: A Theory in Practice in Higher EducationDocument17 pagesAndragogy: A Theory in Practice in Higher EducationAliya NurainiPas encore d'évaluation

- Child Interest SurveyDocument1 pageChild Interest Surveyapi-521246817Pas encore d'évaluation

- DELF B1 Exam Preparation Course Online PDFDocument2 pagesDELF B1 Exam Preparation Course Online PDFYuli Sentana50% (2)

- Multigrade Teaching InsightsDocument4 pagesMultigrade Teaching InsightsCyrill Gabunilas FaustoPas encore d'évaluation

- Laboratory ReportDocument4 pagesLaboratory ReportdharamPas encore d'évaluation

- LET PRE A S2018 Ans Key - Docx Version 1Document12 pagesLET PRE A S2018 Ans Key - Docx Version 1Zhtem Cruzada67% (3)

- Part Iv: Development PlansDocument4 pagesPart Iv: Development Plansjean monsalud100% (1)

- Discourse MakersDocument2 pagesDiscourse MakersLiga DoninaPas encore d'évaluation

- Principle 1 Lesson 4Document5 pagesPrinciple 1 Lesson 4Henry BuemioPas encore d'évaluation

- Coursebook Evaluation 1Document16 pagesCoursebook Evaluation 1api-269809371Pas encore d'évaluation

- Roles of Assessment in TeachingDocument8 pagesRoles of Assessment in Teachingdayah3101Pas encore d'évaluation

- Interview With Reinhold Martin Utopia S Ghost 2010 Architectural Theory ReviewDocument9 pagesInterview With Reinhold Martin Utopia S Ghost 2010 Architectural Theory Reviewveism100% (1)

- Brain Gym For Stroke 2Document16 pagesBrain Gym For Stroke 2Nuriya JuandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Technology NewsletterDocument5 pagesTechnology Newsletterapi-638667083Pas encore d'évaluation

- All Our Futures: Creativity, Culture and EducationDocument243 pagesAll Our Futures: Creativity, Culture and EducationJoaquín Vicente Ramos RodríguezPas encore d'évaluation

- 2015 Lesson Plan Fitness Skills TestDocument6 pages2015 Lesson Plan Fitness Skills Testapi-294542223Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inquiry (5E) Lesson Plan TemplateDocument3 pagesInquiry (5E) Lesson Plan Templateapi-487904244Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pre School CatalogueDocument36 pagesPre School Cataloguemails4gaurav360Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan 3Document3 pagesLesson Plan 3api-312476488Pas encore d'évaluation

- Spa Media Arts Curriculum Guides-EditedDocument20 pagesSpa Media Arts Curriculum Guides-EditedEsti Mendoza83% (6)

- Tim Nauta ResumeDocument3 pagesTim Nauta Resumeapi-311449364Pas encore d'évaluation

- Daily Lesson Plan (Year 5 Cefr) : Pre-Lesson: Lesson Delivery: Post LessonDocument4 pagesDaily Lesson Plan (Year 5 Cefr) : Pre-Lesson: Lesson Delivery: Post LessonMohd Faizul RamliPas encore d'évaluation

- Carer CV TemplateDocument2 pagesCarer CV TemplateLip Stick100% (1)

- Jacob Klein On WonderDocument14 pagesJacob Klein On WonderMayra Cabrera0% (1)

- Learning Styles: Higher Education ServicesDocument8 pagesLearning Styles: Higher Education Servicesandi sri mutmainnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Himachal Pradesh Technical UniversityDocument2 pagesHimachal Pradesh Technical UniversityArun SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Between The LinesDocument250 pagesReading Between The LinesVijay Anand100% (1)

- Ri Action PlanDocument5 pagesRi Action PlanAIN FATIHAH BINTI MOHD KASIM MoePas encore d'évaluation

- Science Forward PlanningDocument8 pagesScience Forward Planningapi-427779473Pas encore d'évaluation

- Text 9Document4 pagesText 9AG Gumelar MuktiPas encore d'évaluation