Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

FIIIINNNNAAAALLL

Transféré par

Giovanni MaciasDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

FIIIINNNNAAAALLL

Transféré par

Giovanni MaciasDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

No.

10-1259 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES ________________ SPRING TERM 2012 _________________

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Petitioner, v. Antoine JONES, Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

Round 1, 6:00 p.m. Round 2, 6:45 p.m. March 20, 2012

Giovanni Garcia Macias 200 McAllister Street San Francisco, CA 94102 (619) 942-7347 Counsel for Respondent

QUESTIONS PRESENTED I. Did the government violate Antoine Jones's Fourth Amendment rights when it used a GPS tracking device to monitor his vehicle continuously for twenty-eight days without a warrant and without Jones's consent? II. Did the government violate Jones's Fourth Amendment rights when it installed a GPS tracking device on the undercarriage of his vehicle without a warrant and without Jones's consent?

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page QUESTIONS PRESENTED...................................................................................... TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................... TABLE OF AUTHORITIES...................................................................................... OPINION BELOW .................................................................................................... JURISDICTION ........................................................................................................ STATEMENT OF THE CASE................................................................................... Preliminary Statement.................................................................................... Statement of Facts.......................................................................................... SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................................................................. ARGUMENT ............................................................................................................. I. THE FBI'S WARRANTLESS USE OF GPS SURVEILLANCE VIOLATED JONES'S FOURTH AMENDMENT RIGHTS BECAUSE HE MANIFESTED A REASONABLE EXPECTATION OF PRIVACY IN HIS TOTAL MOVEMENTS OVER TIME .......................................................... A. Jones's Expectation of Privacy in his Aggregate Movements while Driving is Objectively Reasonable, because a Person's Aggregate Movements Can Reveal Intimate Details of that Person's Life. ........ Jones Manifested a Subjective Expectation of Privacy in his Aggregate Movements. ...................................................................... 2 3 5 7 7 8 8 9 10 12

12

12 19

B. II.

THE WARRANTLESS INSTALLATION OF A GPS TRACKING DEVICE ONTO JONES'S JEEP CONSTITUTED AN UNREASONABLE SEIZURE BECAUSE IT MEANINGFULLY INTERFERED WITH JONES'S POSSESSORY INTERESTS IN HIS JEEP. .................................. A. By Installing the GPS Tracking Device, the Government Converted Jones's Jeep to its Own Purposes, without Jones's Consent or Knowledge.. ....................................................................................... iii

20

20

TABLE OF CONTENTS (CONT.) B. By Installing the GPS Tracking Device, the Government Intruded on Jones's Right to Exclude Uninvited Third Parties from His Property. ............................................................................................. The Intrusiveness of the Government's Interference with Jones's Possessory Interests Outweighs the Government's Interest in Undertaking an Efficient Investigation. .............................................

Page

23

C.

24

CONCLUSION ..........................................................................................................

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) CASES

UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT Berger v. New York, 388 U.S. 41 (1967) .........................................................................................

21

Bond v. United States, 529 U.S. 334 (2000) ....................................................................................... 14, 17, 18, 19 California v. Ciraolo, 476 U.S. 207 (1986) ....................................................................................... California v. Greenwood, 486 U.S. 35 (1988) ......................................................................................... Johnson v. United States, 333 U.S. 10 (1948) ......................................................................................... Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967) ....................................................................................... Kyllo v. United States, 533 U.S. 27, 36 (2001) ................................................................................... Silverman v. United States, 365 U.S. 505 (1961) ....................................................................................... Unites States Department of Justice v. Reporters Committee for Freedom of Press 489 U.S. 749, 757 (1989) ............................................................................... United States v. Jacobson, 466 U.S. 109 (1984) .......................................................................................

14, 15, 19

14, 15

12, 19

Passim

18

21, 22

15, 16

20, 22

United States v. Karo, 468 U.S. 705 (1984) ....................................................................................... 19, 21, 22, 23 United States v. Knotts, 460 U.S. 276 (1983) .......................................................................................

12, 13, 16

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (CONT.) Page(s) United States v. Place, 462 U.S. 696 (1983) ....................................................................................... UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEALS United States v. Garcia, 474 F.3d 994 (7th Cir. 2007) .......................................................................... United States v. Maynard, 615 F.3d 544, 568 (D.C. Cir. 2010)................................................................ United States v. Va Lerie, 424 F.3d 694 (8th Cir. 2005) .......................................................................... STATUTES UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION U.S. Const. amend. IV................................................................................................ FEDERAL STATUTES 21 U.S.C. 841, 846, 851. ....................................................................................... 28 U.S.C. 1254 (1) .................................................................................................. OTHER AUTHORITIES Renee M. Hutchins, Tied Up in Knotts? GPS Technology and the Fourth Amendment, 55 UCLA L. Rev. 409 (2007) ................................................... 13, 16, 18, 19 Viviek Kotharl, Autobots, Decepticons, and Panopticons: The Transformative Nature of GPS Technology and the Fourth Amendment, 6 Crim. L. Brief 37 (2010) ............................................................................................................. 8, 9 7 12 20, 24

22

22

16, 21

vi

No. 10-1259 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

SPRING TERM 2012

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Petitioner, v. Antoine JONES, Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

OPINION BELOW The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit is reported at United States v. Maynard, 615 F.3d 544 (D.C. Cir. 2010).

JURISDICTION The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1254 (1).

STATEMENT OF THE CASE Preliminary Statement On September 16, 2005, the District Court of the District of Columbia granted an order allowing the Federal Bureau of Investigation ("FBI") to install and use a Global Positioning System ("GPS") tracking device on respondent Antoine Jones's Jeep Grand Cherokee, as part of a narcotics investigation. (J.A. 21-26.) The order allowed the agents to track the vehicle for ninety days in any jurisdiction and without interruption. (J.A. 32, 33.) The order required the device to be installed within the boundaries of the district court's jurisdiction in Washington, D.C., no later than ten days after issuance. (J.A. 33.) The FBI installed the GPS device in Maryland, after the installation period had lapsed. (J.A. 250.) Subsequently, the FBI used the GPS tracking device to monitor Jones's movements twenty-four hours a day, for a total of twenty-eight days. (J.A. 250.) The surveillance ended with the arrest of Jones and several alleged co-conspirators on October 24, 2005. (J.A. 225.) Jones and the others were charged with several counts, including conspiracy to distribute and possess with intent to distribute cocaine and cocaine base. (J.A. 224, 225.) In the ensuing jury trial, Jones moved to suppress the evidence obtained from the electronic tracking device. (J.A. 12.) The district court denied the motion. (J.A. 14.) The jury acquitted Jones on all counts except the conspiracy charge, on which it could not reach a verdict; the court declared a mistrial. (J.A. 15, 16.) On March 21, 2007, the government filed a superseding indictment, charging Jones and others with a single count of conspiracy to distribute and to possess with intent to distribute five or more kilograms of cocaine and fifty or more grams of cocaine base. 21 U.S.C. 841, 846,

851. (J.A. 35, 67.) On January 10, 2008, Jones was convicted on this count and sentenced to life in prison, concurrent with ten years of supervised release and ordered to pay $2,100 in restitution. (J.A. 18, 19.) Jones appealed his conviction to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. (J.A. 20.) The court of appeals reversed, holding that Jones's conviction was obtained with evidence acquired in violation of his Fourth Amendment rights. United States v. Maynard, 615 F.3d 544, 568 (D.C. Cir. 2010). The government's petition for a rehearing en banc was denied. (J.A. 4, 5.) On June 27, 2011, this Court granted petitioner's writ of certiorari. (J.A. 6, 223.) Statement of Facts For twenty-eight days, respondent Antoine Jones's every move while driving his Jeep Grand Cherokee was monitored secretly and continuously by the government, without Jones's consent and without a warrant. (J.A. 250.) On September 27, 2005, the F.B.I. attached a GPS tracking device to the undercarriage of Jones's Jeep in Maryland, pursuant to a warrant issued in another jurisdiction and after the warrant's specified installation period had lapsed. (J.A. 100, 250.) The GPS device the FBI used to track Jones was motion activated. (J.A. 87.) While the Jeep was still, the device remained in 'sleep mode,' shut off to conserve energy. (J.A. 129.) When the device sensed motion, it would start collecting and storing coordinate points corresponding to Jones's location while driving his Jeep, along with the date and time of each coordinate point. (J.A. 115, 119.) The GPS device could then relay the location data over a cellular network to the monitoring agents. (J.A. 80.) Agents could retrieve the location data by downloading it to a laptop; then, the agents could print the data or display it on a laptop's screen

using specialized software. (J.A. 82, 114.) The agents could also monitor the Jeep's movements live. (J.A. 78.) Before the GPS device was installed, the FBI, as part of the Safe Streets Task Force, already had extensive surveillance in place. (J.A. 102.) Investigators conducted physical surveillance, parking agents outside a night club Jones owned. (J.A. 103.) Eventually, the investigators installed a stationary pole camera to monitor the club's entrance continuously. (J.A. 104.) Investigators also monitored Jones's phone calls. (J.A. 92.) Once the GPS device was in place, the FBI continued to use a comprehensive mix of telephone, video, physical, and GPS surveillance to monitor Jones's activities. (J.A. 142.) On October 15, 2005, the tracking device's batteries ran out of power and the device stopped collecting location data. (J.A. 111.) Five days later, investigators located Jones's car and replaced the batteries. (J.A. 112, 131, 134.) Using the GPS tracking data, the FBI integrated their physical, video, and phone surveillance to establish that Jones frequented a house on 9508 Potomac Drive and that he often associated with a group of persons believed to be narcotics traffickers who also frequented that house. (J.A. 121-23, 142, 216-22.) On October 24, 2005, the FBI served warrants to search the house on 9508 Potomac Drive, and found ninety-seven kilograms of cocaine, three kilograms of cocaine base, and over $800,000; Jones was not at the house. (J.A. 153,155, 225.) The FBI also searched Jones's Jeep, inside the garage of Jones's home, and found just over $69,000, but no narcotics. (J.A. 182.) The FBI arrested Jones and his alleged co-conspirators. (J.A. 225.)

10

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT The decision of the D.C. Circuit should be affirmed. Under the analytical framework provided in Katz, the use of GPS constituted an unreasonable search under the Fourth Amendment. Jones held a reasonable expectation of privacy in his aggregate movements because a person's aggregate movements can reveal intimate details of his or her life. Moreover, Jones's desire to keep his activities private was manifest. First, Jones referred to his activities using coded language, showing he wished to keep them private. And second, the FBI recognized that if Jones were to be physically followed for an extended period, he would notice and presumably take evasive measures. Furthermore, the installation of the GPS tracking device constituted an unreasonable seizure under the Fourth Amendment. Under the framework set out in Jacobson, the installation was a seizure because the government intruded on Jones's possessory interests, by converting Jones's Jeep from a means of transportation to a means of government surveillance and by infringing Jones's right to exclude others from his property. Under Place, the seizure was unreasonable because the intrusiveness of the government's actions outweigh its interest in conducting more efficient investigations. Because the installation and use of the GPS device constituted both a search and a seizure violative of the Fourth Amendment, this Court should affirm the D.C. Circuit's decision.

11

ARGUMENT I. THE FBI'S WARRANTLESS USE OF GPS SURVEILLANCE VIOLATED JONES'S FOURTH AMENDMENT RIGHTS BECAUSE HE MANIFESTED A REASONABLE EXPECTATION OF PRIVACY IN HIS TOTAL MOVEMENTS OVER TIME. The Fourth amendment provides that the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated." U.S. Const. amend. IV. In Katz v. United States, this Court provided the contemporary analytical framework for Fourth Amendment searches: If the government violates 1) an objectively reasonable expectation of privacy 2) that a person subjectively and manifestly holds, the government has performed a Fourth Amendment search. 389 U.S. 347, 361 (1967) (Harlan, J., concurring). Government 'searches' are presumptively unreasonable if warrantless. Johnson v. United States, 333 U.S. 10, 13-14 (1948). A. Jones's Expectation of Privacy in his Aggregate Movements while Driving is Objectively Reasonable, because a Person's Aggregate Movements Can Reveal Intimate Details of that Person's Life.

When this Court held in United States v. Knotts that "a person traveling in an automobile on public thoroughfares has no reasonable expectation of privacy," it did not mean to extend an open invitation to government surveillance on the public streets. 460 U.S. 276, 281 (1983). In Knotts, this Court expressly set aside the question whether constant, prolonged surveillance is constitutional. Id. at 284. Knotts involved a criminal suspect tracked during a single, one-way drive. Id. at 283. There, this Court cautioned that its holding did not endorse "twenty-four hour surveillance of any citizen of this country." Id. at 284.

12

Yet that is the extent of surveillance at issue here not only did the government track Jones's for twenty-four hours, it did so over twenty-eight days. The case at bar thus exceeds the scope this Court set for the Knotts holding. Knotts is also distinguishable because the type of surveillance Knotts contemplated is far less intrusive than the surveillance at issue here. In Knotts, police used a 'beeper' concealed in a tub of chloroform to track a suspect to his secluded cabin. 460 U.S. at 277. Beepers emit a weak radio signal that a receiver within range can pick up. Renee M. Hutchins, Tied Up in Knotts? GPS Technology and the Fourth Amendment, 55 UCLA L. Rev. 409, 435 (2007). A beeper does not store any information about a vehicle's whereabouts, nor does it transmit the suspect's location per se. Id. at 435. Rather, beepers alert the monitoring officer as the suspect vehicle nears, serving to gauge rough proximity. Id. For that reason, an officer must be within a beeper's limited range for it serve any surveillance purpose at all. Id. GPS tracking devices are very different from beepers. GPS receivers use dedicated satellites to calculate latitude, longitude, and altitude, as well as speed and direction of travel if the receiver is moving. Id. at 417. GPS receivers currently can calculate locations to within two meters. Id. To serve as tracking devices, GPS receivers are coupled with a transmitter, which relays the location data to third parties as distant as the transmitter technology allows. Id. at 418. The motion activated GPS device the FBI used to track Jones was sensitive enough to be set off by the wind. (J.A. 87.) It stored all the location data it gathered, which its transmitter could relay over a cellular network. (J.A. 80.) Accordingly, the monitoring agents were neither limited by time nor distance they could monitor the Jeep's location live from anywhere within reach of a cellular signal, or retrieve the stored history of location information by downloading it

13

to a laptop or by printing it. (J.A. 82, 114.) Because the GPS device stored the location information it gathered, the data could be analyzed long after the tracking itself had ended. As a "legacy" model, the device used to track Jones was less accurate than newer models the FBI uses. (J.A. 86.) The location data the device collected could include variances of fifty to one hundred feet when the device was physically obstructed. (J.A. 81, 141.) Still, the GPS device ultimately collected enough data to fill over two-thousand pages; indeed, the data of a single day, printed in part, amounted to a four-inch stack of paper. (J.A. 109-10, 128.) Accordingly, the capacity for precise, truly remote tracking, and the sheer bulk of data GPS devices can collect and store, sets GPS tracking devices far apart from beepers. By leveraging this enhanced quality and quantity of data that GPS tracking provides, the FBI discovered not just the routes Jones chose to travel, but the routines of his personal life. By doing so, the government intruded on what Jones could reasonably expect should remain private. In Katz, this Court reasoned that "[w]hat a person knowingly exposes to the public . . . is not subject to Fourth Amendment protection." 389 U.S. at 351. Subsequently, this Court has held consistently that what a person exposes to the public does not depend on what that person expects members of the public can possibly or lawfully come to know, but on what he or she reasonably expects members of the public can plausibly to come to know. See California v. Greenwood, 486 U.S. 35, 40 (1988); California v. Ciraolo, 476 U.S. 207, 213-14 (1986); Bond v. United States, 529 U.S. 334, 338-39 (2000). For example, in Ciraolo, police investigators chartered a private plane to observe a suspect's walled-off yard from 1000 feet overhead; the investigators identified a large plot of marijuana plants growing in the yard. Id. at 209. This Court held that "[i]n an age where private

14

and commercial flight in the public airways is routine," an expectation that crops growing in an uncovered field should remain private is not objectively reasonable. 476 U.S. at 214. Similarly, in Greenwood, an investigator obtained the discarded trash bags of a suspected narcotics dealer from a trash collector, and found drug paraphernalia inside. Id. at 37-38. This Court ruled that any expectation of privacy the suspect held in his discarded trash was not reasonable because the trash collector or any passerby could plausibly inspect it. Id. at 40. Jones's aggregate movements over the course of a month were not plausibly revealed to any single member of the public. As Jones drove along public streets, Jones's Jeep could be viewed by any member of the public near enough to see it. Each individual trip was as exposed to public scrutiny as the uncovered field in Ciraolo or the discarded trash bags in Greenwood. Still, that each person who happened to view the Jeep, during the FBI's round-the-clock, monthlong surveillance would collaborate to create an uninterrupted log of Jones's turn-by-turn movements is so implausible as to defy reasonable belief. Yet that is exactly what the FBI's longterm GPS surveillance revealed. For these reasons, the fact that any one of Jones's movements could be viewed by the public does not dispense with his claim to an objectively reasonable expectation of privacy in his aggregate movements. Jones's expectation that his aggregate movements should remain private is also objectively reasonable because knowing a person's total movements can reveal intimate details of that person's life not revealed by any single movement. In Unites States Department of Justice v. Reporters Committee for Freedom of Press, respondents sought to acquire summaries of the criminal records of certain individuals, their 'rap sheets.' 489 U.S. 749, 757 (1989). This Court refused the requested disclosure because, though

15

"individual events in those [rap sheets were] matters of public record," the Court recognized a "distinction, in terms of personal privacy, between scattered disclosure of the bits of information contained in a rap sheet and revelation of the rap sheet as a whole." 489 U.S. at 764. In the present case, investigators did not simply use the GPS data to identify Jones's location on the public streets, as did investigators in Knotts who used the beeper simply to follow the suspect to his remote cabin. 460 U.S. at 277. Here, the FBI used GPS tracking to determine Jones's role in an alleged trafficking conspiracy. (J.A. 22.) In conjunction with other forms of surveillance, the FBI used the GPS data to learn the precise patterns of Jones movements and thus infer his activities and associates. (J.A. 121-23, 142, 216-22.) Analogous to the rap sheets in Reporters Committee, the mass of data that GPS tracking aggregates allows the FBI to piece together the "scattered . . . bits of information" that Jones's discrete movements represented, into a completed whole. 489 U.S. at 764. However, GPS tracking devices do not differentiate between criminal and non-criminal activity. Viviek Kotharl, Autobots, Decepticons, and Panopticons: The Transformative Nature of GPS Technology and the Fourth Amendment, 6 Crim. L. Brief 37, 43 (2010). In contrast to the rap sheets which could only reveal criminal activities, the 2,200 pages of GPS data could be used to extrapolate details of Jones's personal affairs unrelated to the investigation. See Kotharl, 6 Crim. L. Brief at 43. For example, a suitably motivated FBI agent could have determined whether Jones attended a church, and if so, how often. See Hutchins, 55 UCLA L. Rev. at 409. In this manner, agents could have inferred Jones's religion, or given other movement patterns, Jones's political leanings, personal habits, or vices. See Id. For these reasons, GPS tracking reveals more that facts about a person's movements; it can reveal facts about a person's way of life.

16

This Court has held that expectations of privacy involving less intrusive government action are reasonable and should accordingly find Jones's subjective expectation of privacy to be reasonable. In Katz, the government placed an electronic listening device on the exterior of a telephone booth from which the government suspected Katz conducted criminal activity. 389 U.S. at 348. The government monitored and recorded six of Katz's telephone calls, each lasting approximately three minutes. Id. at 354 n. 14. This Court held that by enclosing himself in a transparent, public telephone booth, Katz enjoyed a reasonable expectation of privacy in what he said. Id. at 352. Likewise, in Bond, a Border Patrol Agent squeezed a bus passenger's luggage to inspect its contents. 529 U.S. at 336. This Court held that although Bond could not reasonably expect privacy over having his luggage handled, he did enjoy a reasonable expectation of privacy over having his luggage squeezed. Id. at 338-39. In the present case, the FBI's GPS monitoring of Jones's movements far exceeded both the duration and scope of surveillance of each of these cases. Here, the GPS surveillance took place over twenty-eight days, as opposed to the six, three-minute calls in Katz or the mere moments Bond's luggage was inspected in Bond. The difference in duration serves to make the GPS surveillance at issue here more intrusive than that in Katz or Bond. Similarly, the GPS surveillance provided much more context than did the surveillance in Katz or Bond. The "Wind Track" software plotted Jones's every movement onto a map, providing the exact time, date, as well as the streets on which Jones traveled. (J.A. 114-15, 119.) This allowed the government to integrate its physical, video, and phone surveillance to try to

17

show that Jones was not an incidental visitor to the drug house nor the casual acquaintance of a group of alleged traffickers. (J.A. 121-23, 142, 216-22.) Indeed, it was through the GPS data that the FBI first linked Jones to the drug house. (J.A. 122.) In Katz, the listening device only captured Katz's end of his brief conversations, revealing little about Katz's interlocutor(s). 389 U.S. at 348. The agent in Bond could not know, by squeezing Bond's luggage, the origin of the narcotics within, nor their destination or intended use. The agent's tactile exploration could not so much as hint at who had sent the narcotics nor who would receive them. The degree of context a GPS device provides serves to make it more intrusive, not less, than government action that this Court has held violated reasonable expectations of privacy. The intrusive potential of GPS monitoring is especially patent when considering, as this Court has said it must, "more sophisticated systems that are already in use or in development." Kyllo v. United States, 533 U.S. 27, 36 (2001). Today, differential GPS (DGPS) receivers can calculate locations to within centimeters. Hutchins, 55 UCLA L. Rev. at 417-18. Whereas the GPS device used to track Jones worked best outdoors when free from obstructions, contemporary devices work equally well indoors and out. Id. at 420. Contemporary GPS devices are becoming ever more compact. Id. at 419. The Los Angeles Police Department deploys GPS devices small enough to be fired as "darts" during high speed pursuits, enabling monitoring officers to track the suspect vehicle in real time from police headquarters. Id. at 418-19. A GPS device measuring less than five cubic inches and weighing slightly more than three ounces is on the market today. Id. at 420-21. This means that GPS devices are now small enough to secretly track an individual and/or her personal effects, indoors or out, with pinpoint accuracy. Id. at 458.

18

Moreover, as GPS satellites can support a limitless number of GPS receivers, government agents have the technical capacity to engage in tracking on nearly any scale. Hutchins, 55 UCLA L. Rev. at 418. The point is not that such Orwellian government surveillance is at hand. The point is that on the standard the government urges, even such extensive and total surveillance would lie beyond the Fourth Amendment's reach. Likewise, the point is not to deprive law enforcement of an efficient and powerful surveillance tool. The point is simply to condition its extended use on the granting of a warrant, thus placing the decision whether to deploy powerful surveillance technologies against members of the American public with "a neutral and detached magistrate," not an "officer engaged in the often competitive enterprise of ferreting out crime." Johnson v. United States, 333 U.S. 10, 13-14 (1948). B. Jones Manifested a Subjective Expectation of Privacy in his Aggregate Movements.

Jones manifested a desire to keep his activities private, as required by the Katz test. 389 U.S. at 361. An individual manifests a subjective expectation of privacy when he takes overt steps to maintain privacy in something. Compare Ciraolo, 476 U.S. at 211-12 (suspect's uncovered field did not manifest an expectation of privacy from aerial observation), with Bond, 529 U.S. at 338 (suspect manifested an expectation of privacy in his bag's contents by "using an opaque bag and placing that bag directly above his seat"). Here, in intercepted telephone calls, Jones seems to use coded terms, possibly to refer to contraband, such as "ticket, small ticket, half ticket, VIP ticket." (J.A. 168.) Although the FBI monitored Jones's telephone calls longer than it used GPS tracking, the record does not indicate a

19

single departure from the coded language where Jones mentioned narcotics openly. (J.A. 93.) This denotes an overt desire to keep his activities private. To be sure, there is no evidence that Jones tried to evade public notice on any single trip by, say, taking rural roads. Yet the FBI admits that following a vehicle for extended periods is "usually not a very good idea . . . [u]nless you want them to know you're following them." (J.A. 97.) Indeed, the FBI decided to track Jones remotely through GPS surveillance because they feared that if they were to follow Jones's Jeep using physical surveillance, Jones would notice and presumably avoid them. (J.A. 107.) The fact that Jones did not try to keep single trips hidden but likely would evade long term physical observation manifests an intent to keep the latter private. II. THE WARRANTLESS INSTALLATION OF A GPS TRACKING DEVICE ONTO JONES'S JEEP CONSTITUTED AN UNREASONABLE SEIZURE BECAUSE IT MEANINGFULLY INTERFERED WITH JONES'S POSSESSORY INTERESTS IN HIS JEEP. A Fourth Amendment 'seizure' occurs when "there is some meaningful interference with an individual's possessory interests in [his or her] property. United States v. Jacobson, 466 U.S. 109, 113 (1984). A 'seizure' is unreasonable if the "nature and quality of the intrusion" on an individual's possessory interests outweighs the "importance of the governmental interests alleged to justify the intrusion." See United States v. Place, 462 U.S. 696, 703 (1983). A. By Installing the GPS Tracking Device, the Government Converted Jones's Jeep to its Own Purposes, without Jones's Consent or Knowledge.

When the FBI attached the GPS tracking device, the Jeep ceased to serve exclusively as Jones's means of transportation; the Jeep coupled with the GPS device became a sophisticated

20

means of government surveillance. This interference is enough to constitute a seizure under this Court's existing Fourth Amendment jurisprudence. A seizure may take place even if a physical deprivation of property does not occur. See Berger v. New York, 388 U.S. 41, 56-57, 59 (1967). For example, in Berger, investigators secretly placed a recording device in a suspect's office and recorded his conversations for two weeks. 388 U.S. at 44-45. As a mere recording of the suspect's voice, the surveillance did not physically deprive the suspect of anything. Kotharl, 6 Crim. L. Brief at 43. This Court held that by recording the suspects conversations, the government committed a Fourth Amendment seizure. Id. at 59. When the government usurps the functions of private property to advance government surveillance, it violates the Fourth Amendment. Silverman v. United States, 365 U.S. 505, 511 (1961). In Silverman, police officers used a 'spike mic' listening device to eavesdrop on the conversations of criminal suspects while in a building the suspects owned. 365 U.S. at 506. The officers inserted a foot long spike under a baseboard, making contact with the heating duct of the suspects building. Id. 506-07. The spike mike picked up the sound vibrations of the suspect's voice resonating through the heating system. Id. at 507. By doing this, the officers effectively converted the heating system into "a giant microphone, running through the entire house occupied by appellants." Id. at 509. This Court held that "by usurping part of the petitioners house or office," the officers violated the suspects' Fourth Amendment rights. Id. at 511-12. To constitute a seizure, a government intrusion must be more than a mere "technical trespass." See United States v. Karo, 468 U.S. 705, 713 (1984). In Karo, a criminal suspect unknowingly purchased a can of ether with a 'beeper' hidden inside. Id. at 708. The Karo

21

majority reasoned that since the 'beeper' simply took up space in the can, its presence did not meaningfully interfere with any possessory interests. 468 U.S. at 713. More recently, Judge Posner echoed Karo, holding that the installation of a GPS device was not a seizure because the device "did not affect . . . driving qualities, did not draw power from the car's engine or battery, did not take up room that might otherwise have been occupied by passengers or packages, [nor] even alter the car's appearances." United States v. Garcia, 474 F.3d 994, 997 (7th Cir. 2007). GPS tracking devices do much more than fill space. Seizure analysis encompasses two elements: 1) there must exist a possessory interest; and 2) the government must meaningfully intrude on that interest. See Jacobsen, 466 U.S. at 703. If a possessory interest exists, the government intrudes on it if it exercises dominion and control over that interest. Id. at 120-21. This court has recognized, albeit in dissent, that a property owner has an exclusive right to use his property for his own purposes. Karo, 468 U.S. at 729 (Stevens, J., dissenting). The exercise of dominion and control over that right is more than a trespass; it constitutes a tort of conversion. United States v. Va Lerie, 424 F.3d 694, 702-03 (8th Cir. 2005). Here, the Jeep was Jones's primary means of transportation. (J.A. 182, 214.) When Jones drove it, be it to his nightclub or to the gym, he likely did not intend that his Jeep serve as a beacon, alerting the government of his every turn. Yet the moment the FBI attached the GPS device to Jones's car, the Jeep stopped serving Jones's exclusive purposes. As with the heating duct in Silverman, the government converted Jones's Jeep to serve its purpose to track Jones, without informing Jones nor seeking his consent. Consequently, the government's intrusion went beyond the volume of space the GPS device filled and beyond the nominal additional power the Jeep expended because of the added weight. The attachment of the GPS device transformed

22

Jones's entire Jeep into a broadcaster of Jones's movements. Although the government did not deprive Jones of the possession of his Jeep, just as the police in Berger did not deprive the suspects of their voices by recording them, the government intruded upon Jones's possessory rights. By doing this, the government seized Jones's property within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. B. By Installing the GPS Tracking Device, the Government Intruded on Jones's Right to Exclude Uninvited Third Parties from His Property.

A property owner may, of right, exclude "all the world" from his property; the FBI flouted this right by physically attaching the GPS device to Jones's Jeep. Karo, 468 U.S. at 729 (Stevens, J., dissenting). Although this Court seemingly dismissed that mere intrusions on the right to exclude constituted a seizure in Karo, the intrusiveness of the installation in the present case exceeds that considered in Karo. Id. at 713. In Karo, the beeper was installed on the permission of a third party who owned the can of ether and later sold it to the suspect. Id. at 708. Consequently, the beeper was not installed directly onto the suspect's car; it was hidden in an item he purchased. Moreover, because the suspect purchased the can, he arguably accepted its contents, tracking device and all. On these facts, it stands to reason that the this Court found the interference too muted to constitute a seizure. Id. at 713. Here, conversely, no third party with a possessory interest in Jones's Jeep authorized the FBI to install the GPS device, nor did Jones purchase the Jeep with the device already in place. To the contrary, the FBI directly attached the device onto the Jeep's undercarriage, without intermediaries and without any permission. (J.A. 100.) It exerted dominion and control over the

23

place in the undercarriage where the device was attached. Although the undercarriage is a part of the car's exterior and thus is accessible to the public, the undercarriage contains vital components of a car's drivetrain and motor. For this reason, a car owner has an especially acute interest in barring third parties from introducing foreign objects into the undercarriage. Accordingly, when the FBI attached the GPS device, it flouted Jones's right to exclude others from his property and thereby undermined a fundamental possessory interest as proscribed by the Fourth Amendment. C. The Intrusiveness of the Government's Interference with Jones's Possessory Interests Outweighs the Government's Interest in Undertaking an Efficient Investigation.

The government's intrusion on Jones's right to use his Jeep for his exclusive purposes and on Jones's right to bar uninvited interference with his Jeep is not justified by the government's interests in engaging in more efficient surveillance. Such an imbalance between the intrusiveness of a government seizure and the government's countervailing interests in conducting the seizure activates Fourth Amendment protections. Place, 462 U.S. at 703. The FBI installed the GPS device on Jones's Jeep because they judged it more efficient than long term visual tracking, which was difficult and burdensome to achieve successfully. (J.A. 107.) Visual tracking involves rotating several vehicles to follow the target vehicle in an effort to avoid detection. (J.A. 97.) GPS surveillance represents a cost effective alternative to visual surveillance. Still, FBI agents testified that the data collected from the GPS surveillance was not strictly necessary to connect Jones with the alleged traffickers and drug house. (J.A. 139.) Indeed, besides the GPS surveillance, the FBI used video, telephone, photographic, and visual surveillance to monitor Jones's activities.

24

The government's interest in using efficient GPS surveillance did not outweigh the intrusiveness of that surveillance, especially given that the government already had extensive non-GPS surveillance in place. As has been shown, the GPS device installation severely invaded Jones's possessory rights: the government converted Jones's Jeep from a personal means of transportation, to a government means of surveillance, ignoring Jones's right to exclude strangers from sensitive areas of his property. Nothing in the record demonstrates an urgent need for the government to infringe Jones's possessory rights in this way. There is no evidence that life or limb was at stake or even that Jones might flee. Because the GPS device was not strictly necessary to advance the government's interests, and because Jones's possessory interests were so severely infringed, the installation of the GPS device constitutes an unreasonable search within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. CONCLUSION The government's unwarranted installation and use of the GPS tracking device was unconstitutional. The use of GPS technology allowed the government to discover intimate details of Jones's daily life, usually shielded from public scrutiny. This constituted an unreasonable search. The installation of the GPS device, which the FBI admitted was unnecessary to their investigation, converted Jones's personal means of transportation into a means of government surveillance and flouted Jones's right to exclude. This constituted an unreasonable seizure. For these reasons, Respondent respectfully requests that this Court AFFIRM the decision of the D.C. Circuit, and uphold the vigorous constitutional protections of property and privacy.

25

Dated: March 1, 2012

Respectfully Submitted, _____________________ Giovanni Garcia Macias Counsel for Respondent

26

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Sihi Pompa LPG API 610Document1 pageSihi Pompa LPG API 610Andry RimanovPas encore d'évaluation

- Muji Into Denmark MarketDocument13 pagesMuji Into Denmark MarketTròn QuayyPas encore d'évaluation

- 5d814c4d6437b300fd0e227a - Scorch Product Sheet 512GB PDFDocument1 page5d814c4d6437b300fd0e227a - Scorch Product Sheet 512GB PDFBobby B. BrownPas encore d'évaluation

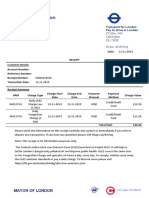

- Transport For London Pay To Drive in London: PO Box 344 Darlington Dl1 9qe TFL - Gov.uk/drivingDocument1 pageTransport For London Pay To Drive in London: PO Box 344 Darlington Dl1 9qe TFL - Gov.uk/drivingDanyy MaciucPas encore d'évaluation

- Java Programming Unit5 Notes PDFDocument110 pagesJava Programming Unit5 Notes PDFVishnu VardhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Pumpkin Cultivation and PracticesDocument11 pagesPumpkin Cultivation and PracticesGhorpade GsmPas encore d'évaluation

- Openness and The Market Friendly ApproachDocument27 pagesOpenness and The Market Friendly Approachmirzatouseefahmed100% (2)

- Synergy Elektrik (PVT.) LTD PDFDocument3 pagesSynergy Elektrik (PVT.) LTD PDFMuhammad KashifPas encore d'évaluation

- Novozymes IPRDocument19 pagesNovozymes IPRthereisaneedPas encore d'évaluation

- Landini Tractor 7000 Special Parts Catalog 1820423m1Document22 pagesLandini Tractor 7000 Special Parts Catalog 1820423m1katrinaflowers160489rde100% (122)

- Australian Car Mechanic - June 2016Document76 pagesAustralian Car Mechanic - June 2016Mohammad Faraz AkhterPas encore d'évaluation

- IDS701Document26 pagesIDS701Juan Hidalgo100% (2)

- Lets Talk About Food Fun Activities Games Oneonone Activities Pronuncia - 1995Document1 pageLets Talk About Food Fun Activities Games Oneonone Activities Pronuncia - 1995IAmDanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Megohmmeter: User ManualDocument60 pagesMegohmmeter: User ManualFlavia LimaPas encore d'évaluation

- The 360 Degree Leader J MaxwellDocument2 pagesThe 360 Degree Leader J MaxwellUzen50% (2)

- ClientDocument51 pagesClientCarla Nilana Lopes XavierPas encore d'évaluation

- 8th Mode of FinancingDocument30 pages8th Mode of FinancingYaseen IqbalPas encore d'évaluation

- Output LogDocument480 pagesOutput LogBocsa CristianPas encore d'évaluation

- CV HariDocument4 pagesCV HariselvaaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Experiment No 9 - Part1Document38 pagesExperiment No 9 - Part1Nipun GosaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Universal Beams PDFDocument2 pagesUniversal Beams PDFArjun S SanakanPas encore d'évaluation

- Pat Lintas Minat Bahasa Inggris Kelas XDocument16 pagesPat Lintas Minat Bahasa Inggris Kelas XEka MurniatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Fss Operators: Benchmarks & Performance ReviewDocument7 pagesFss Operators: Benchmarks & Performance ReviewhasanmuskaanPas encore d'évaluation

- Surname 1: Why Attend To WMO? Who Would Not Trust The Brand That Their Friends Strongly Recommend? It IsDocument4 pagesSurname 1: Why Attend To WMO? Who Would Not Trust The Brand That Their Friends Strongly Recommend? It IsNikka GadazaPas encore d'évaluation

- Elo BLP Neutral en Web.5573Document8 pagesElo BLP Neutral en Web.5573Ichsanul AnamPas encore d'évaluation

- IA1 - Mock AssessmentDocument3 pagesIA1 - Mock AssessmentMohammad Mokhtarul HaquePas encore d'évaluation

- Design and Analysis of Intez Type Water Tank Using SAP 2000 SoftwareDocument7 pagesDesign and Analysis of Intez Type Water Tank Using SAP 2000 SoftwareIJRASETPublicationsPas encore d'évaluation

- LSM - Neutral Axis Depth CalculationDocument2 pagesLSM - Neutral Axis Depth CalculationHimal KaflePas encore d'évaluation

- Document 3Document6 pagesDocument 3Nurjaman SyahidanPas encore d'évaluation

- Presentation On Plant LayoutDocument20 pagesPresentation On Plant LayoutSahil NayyarPas encore d'évaluation