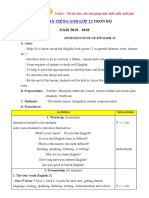

Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Clauses and Sentences

Transféré par

bbyk117Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Clauses and Sentences

Transféré par

bbyk117Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Clauses and Sentences

Definition Clauses and sentences in Quirk et al. Clauses and sentences in transformational-generative grammar Clauses in functional sentence perspective

Clauses and Sentences

Clause is the largest grammatical unit smaller than a sentence. The clause is a traditional and fundamental unit of sentence structure, though the term is not used by all grammarians in exactly the same way. Traditionally, a clause is a grammatical unit consisting of a subject and a predicate, and every sentence must consist of one or more clauses.

Clauses and Sentences

There has always been some confusion in the definitions of the two terms clause and sentence. Traditional grammars reserve the term sentence for the larger or maximal sentence and talk about the sentences of which it is composed, the minimal sentences, as clauses.

Clauses and Sentences in Quirk et al.

Recently, some grammarians, notably Quirk and his advocates, have been extending the term clause to every unit containing a verb, including many units traditionally regarded only as phrases and this extended usage is now very widespread. For example, the following sentences are all regarded as containing two clauses:

Clauses and Sentences

1. Susies heavy smoking is affecting her health. 2. Susie wants to buy a new car. 3. Having finished her dinner, Susie reached for her cigarettes. 4. Fast cars in big cities is dangerous.

Simple and Multiple Sentences

A simple sentence consists of a single independent clause: You can borrow my car. A multiple sentence contains two or more clauses. Multiple sentences are either compound or complex.

Simple and Multiple Sentences

A compound sentence contains two or more co-ordinate clauses as its immediate constituents. The principle of a rocket motor is simple, but large, powerful rockets are very complicated machines. Not only does the atmosphere give us air to breathe, but also it filters out harmful sun rays.

Simple and Multiple Sentences

A complex sentence contains two or more clauses, at least one of which being the independent superordinate clause, the others being sub-ordinate clauses functioning as its immediate constituents. These constituents are themselves clause elements within the structure of the superordinate clause.

Simple and Multiple Sentences

Fossils in 500-million-year-old rocks demonstrate that life forms in the Cambrian period were mostly marine animals capable of secreting calcium to form cells. You can borrow my car if you need it. Too nervous to reply after other speakers had praised her devotion to duty, Margaret indicated that she would speak later.

Simple and Multiple Sentences

Important note: the term simple sentence is used for an independent clause that does not have another clause functioning as one of its elements (i.e. as S, O, C, or A). So, for example, a sentence is regarded as simple if it contains a clause functioning as post-modification of a noun phrase within the superordinate structure of the sentence:

Simple and Multiple Sentences

Homo erectus is the name commonly given to the primate species from which humans are believed to have evolved. You can borrow the car that belongs to my sister. In the above sentences, the complexity is at the level of the phrase, not at the level of the sentence or clause. Therefore, they are regarded as simple sentences.

Simple and Multiple Sentences

A simple sentence is so called because it contains only one independent superordinate clause. It is not necessarily simple in a non-technical sense. On the contrary, a simple sentence may be very complicated because its immediate constituent phrases are complex:

Simple and Multiple Sentences

Thus, the following complicated sentence is a simple sentence: On the recommendation of the committee, the temporary chairman, who had previous experience of the medical issues concerned, made the decision that no further experiments on living animals should be conducted in circumstances that might lead to unfavorable press publicity.

Simple and Multiple Sentences

The term simple sentence is frequently used by grammarians other than Quirk and his advocates for an independent clause that does not contain another clause, regardless of whether the contained clause is an immediate constituent of the sentence or not. In some grammars, non-finite and verbless constructions are considered phrases rather than clauses, whereas they are treated as clauses by Quirk because of their being analyzable into clause elements.

Semantic role of clause elements

S: agentive, external causer, instrument, affected, recipient, positioner, locative, temporal, eventive, prop it, Od: affected, locative, resultant, cognate, eventive, instrumental Oi: recipient, affected Cs/Co: attribute

Participants: entities realized by noun phrases, whether such entities are concrete or abstracts: John found a good place for the magnolia tree. (3 participants) Agentive participant = the most typical semantic role of a subject in a clause that has a direct object = the agent/doer of the action/the animate causing the happening denoted by the verb:

Typical semantic role of clause elements

Typical semantic role of clause elements

The child tore my book. Affected/patient/objective participant = the most typical role of the direct object = animate or inanimate which does not cause the happening denoted by the verb, but is directly involved in some other way: Margaret is mowing the grass.

Typical semantic role of clause elements

Recipient/dative participant = the most typical role of the indirect object = the animate being that is passively implicated by the happening or state: We paid them the money. Benefactive/beneficiary participant/ intended recipient = when the indirect object is expressed by a for-phrase: She made a scarf for her son.

Recipient participant and beneficiary participant can co-occur in the same clause: She gave me a scarf for her son. Inanimate indirect object does not qualify for the recipient role: I have found a place for you = I have found you a place. I have found a place for the magnolia tree. Not * I have found the magnolia tree a place.

Typical semantic role of clause elements

Typical semantic role of clause elements

Attribute = the typical semantic role of a subject complement and an object complement Identification attribute: His response to the reprimand seemed a major reason for his dismissal. Characterization attribute: The operation seemed a success.

Typical semantic role of clause elements

Only identification attributes normally allow reversal of subject and complement without affecting the semantic relations in the clause, if the copula is be: Kevin is my brother = My brother is Kevin. Only characterization attributes can also be realized by adjective phrases: The operation seemed successful.

Typical semantic role of clause elements

Identification attributes are normally associated with definite noun phrases. Noun phrases used as characterization attributes are normally indefinite. We made John our representative. (identification attribute) I consider the operation a success. (characterization attribute)

Typical semantic role of clause elements

If the identification attribute is a noun phrase with an optionally omitted determiner, subject complement reversal cannot occur: Joan is president of the company. Joan is the president of the company = The president of the company is Joan.

Typical semantic role of clause elements

Current attribute = normally with verbs used statively She remained silent. I want my food hot. Resulting attribute = with verbs used dynamically Shell make a good worker. The heat turned the milk sour.

Other semantic roles of clause elements

External/force causer subjects: the unwitting inanimate cause of an event: The electric shock killed him. Instrument subject: the inanimate entity which an agent uses to perform an action or instigate a process The computer has solved the problem. Affected subject: with intransitive verb: Jack fell down.

Other semantic roles of clause elements

In certain intransitive constructions with affected subjects, an adverbial is generally required: Her books translate well. (= Her books are of the type that are good in translation). The sentence reads clearly. The sheets washed easily. My teapot pours without spilling.

Other semantic roles of clause elements

Intransitive and transitive constructions do not always correspond: Her books translate well. (= Her books are of the type that are good in translation). The translator translated her book well. = (He was a good translator of her books). The car ran down the hill. (= Somebody ran the car or the car ran by itself due to some external force). We ran the car down the hill.

Other semantic roles of clause elements

Recipient subject: with such verbs as have, own, posses, benefit from, hear (but not listen to), see (but not look at) I have a radio. (My father has bought it for me). Positioner subject: with intransitive stance verbs such as sit, stand, live, lie, stay, remain, and with transitive verbs related to stance verbs such as carry, hold, keep, wear.

Other semantic roles of clause elements

I have lived in London most of my time. They are staying at a motel. Locative subject: designating the place of the state or action: Los Angeles is foggy. Temporal subject: designating the time of the state or action: Yesterday was a holiday.

Other semantic roles of clause elements

Eventive subject: designating an event: The Norman invasion took place in 1066. Prop-it subject: no participant is required; the subject functions by the prop word it which has little or no semantic content. The clauses often signify time, atmospheric conditions, or distance: Its too windy in Chicago.

Other semantic roles of clause elements

Locative object: with such verbs as walk, swim, pass, jump, turn, leave, reach, surround, cross, climb: She swam the river = She swam across the river. Resultant object: whose referent exists only by virtue of the activity indicated by the verb (with such verbs as paint, make, invent, design, bake, write) John has painted a new picture.

Other semantic roles of clause elements

Cognate object: the noun head is semantically and morphologically related to the verb: (sing-song/diedeath/breathe/breath/live-life/fight-fight) She lived a good life. Eventive object: de-verbal nouns preceded by a common verb of general meaning, semantically an extension of the verb bearing the major part of the meaning:

Other semantic roles of clause elements

Have an argument, do a translation, do some painting, get a glance at, give advice to, make an agreement with, offer an apologize, pay attention to, put emphasis on, take a breath Instrumental object: We employed a computer for our calculations. Affected indirect object: She gave me a push.

The complex sentence

A complex sentence is like a simple sentence in that it consists of only one main clause, but unlike a simple sentence it has one or more subordinate clauses functioning as an element of the sentence. Subordination is an asymmetrical relation: the sentence and its subordinate clauses are in a hypotactic relationship, that is they form a hierarchy in which the subordinate clause is a constituent of the sentence as a whole.

The complex sentence

Subordination is not the only factor that enters into either the length or the complexity of sentences, when complexity is understood in a non-technical sense. Phrases may be complex in the degree of their modification; the vocabulary may be obscure because of their compression; nominalizations may be more difficult to understand than corresponding subordinate clauses; the content of the sentence may presuppose knowledge that is not generally available.

The complex sentence

Notes on terminology: Main clauses have also been called principal clauses or head clauses. Subordinate clauses have also been called dependent, embedded, included, constituent, and syntactically bound clauses. A matrix clause (a main clause as termed by other grammarians rather than Quirk et al.) is the superordinate clause minus its subordinate clauses.

The complex sentence

Sentence Main/superordinate clause S V A She telephoned subordinate clause matrix clause Subordinator S V A While you were out

Structural classification of clauses

Finite clause: a clause whose verb element is finite (i.e. it shows tense/aspect) Non-finite clause: a clause whose verb element is non-finite (i.e. it shows no tense/aspect) Verbless clause: a clause that does not have a verb element, but is nevertheless capable of being analyzed into clause elements:

Structural classification of clauses

Too nervous to reply after other speakers had praised her devotion to duty. Margaret indicated that she would speak later. One should avoid taking a trip abroad in August where possible. He looked remarkably well, his skin clear and smooth.

Structural classification of clauses

Notes: A structure is recognized as a clause only when it is describable in terms of clausal rather then phrasal structure, i.e. it can be syntactically analyzed as a sequence of S, V, and O. I enjoyed part-time teaching. (part-time teaching = noun phrase) I enjoyed teaching undergraduates. (teaching undergraduates = clause) I enjoyed teaching. (teaching = structurally ambiguous, which can be either a phrase or a clause)

Constituent structure of clauses and sentences in transformational-generative grammar A grammar for positive declarative sentences (i) S NP VP (ii) VP VGp NP (iii) NP Det N (iv) VGp Aux V (v) Aux Tns (M) (have en) (be ing) (vi) Tns {Past, Pres} (vii) M {will, can} (viii) V {see} (ix) N {John, Mary} (x) Det {a, an, the, }

Constituent structure of clauses and sentences in transformational-generative grammar

John will have seen Mary. S NP N VGp Aux Tns M John Pres will have en

VP V

NP N

see Mary

Constituent structure of clauses and sentences in transformational-generative grammar Positive declarative sentences through passivization S NP VP N VGp PP Aux V Prep NP Tns M Mary Pres will have en be en see by Mary

Constituent structure of clauses and sentences in transformational-generative grammar

S

NP Det N

PP Adv Adj Prep NP Det N This boy must seem incredibly stupid to that girl The team can rely on my support. His brother will put the vodka into the drink.

VP AdjP

Constituent structure of clauses and sentences in transformational-generative grammar

S

NP

VP

V NP Aux V Det N M Perf Prog VS Prog

He might have been writing

letter

Constituent structure of clauses and sentences in transformational-generative grammar

Interrogative sentences: S Aux NP VP Will Mary buy that car? Compound and complex sentences S S1 C S2 Mary might think that he will resign. S C S1 S2 When I saw the man, he was carrying a gun.

Clauses and sentences in FSP

The Praguean Functional Sentence Perspective (FSP) takes as its central concepts the sequencing and organization of information-conveying sentential units in terms of their TopicComment Articulation (TCA).

Clauses and sentences in FSP

TCA is a functional approach which views the sentence as being divided into two parts, Topic and Comment, often referred to in several notational variants (though this conflation is not always universally approved of): theme (topic, known/given information, presupposition, basis); rheme (focus, comment, unknown/new information).

Clauses and sentences in FSP

Dane (1974: 113) called the rheme as the conveyor of the new, actual information, and the theme as a relevant means of the construction. The theme thus exists to create topic continuity by providing a linkage with prior discourse, while the rheme is the real reason for communication. Halliday (1970) metaphorically compared theme to a peg on which the message (i.e. the rheme) is hung.

Clauses and sentences in FSP

Speakers tend to start the conversation with something new in their mind (potentially becoming the rheme) which they wish to communicate and they use the theme as the point of departure (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004:64).

Clauses and sentences in FSP

Werth (1984:219) considered it important to give a reason for the TCA and offered a two-sided explanation for the process. The first reason is psychological and expresses speakers wish to construct a message in a maximally effective way when conveying its meaning. The second reason is a pragmatic one with respect to Grices Maxim of Manner in which speakers should try to avoid ambiguity by speaking in an orderly and unambiguous way.

Clauses and sentences in FSP

Some researchers e.g. Clark and Clark (1977) and Paprott and Sinha (1987) have either implicitly or explicitly conflated the notion of given and new in the notion of themerheme and topic-comment, however, this assumption is not universally advocated.

Clauses and sentences in FSP

Halliday (1967); Halliday and Matthiessen (2004), Fries (1994) and Lyons (1970) point out that though related and both being textual functions, given-new and themerheme are not homogeneous. Theme and rheme are within thematic structure and are speaker-oriented whereas given and new information structure and listener-oriented (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004:93).

Clauses and sentences in FSP

Fries (1994) claimed that it would be a fallacy to assume some absoluteness in the correlation between new and rheme and given and theme despite the fact that in general, rheme tends to be new information and theme given information. Many themes, especially marked themes are intended as new information.

Clauses and sentences in FSP

Similarly, not all rhemes are presented as bearing new information. Moreover, some new information may encompass the theme and some given information the rheme. These distinctions can be explained in the following examples taken from Halliday (1967: 200) and Halliday and Matthiessen (2004:94) respectively:

Clauses and sentences in FSP

John [saw the play yesterday]. Supposing the above utterance is a direct response to a previous question in the discourse, say Who saw the play yesterday? in that case, John bears the new information though being the theme. I havent seen you for ages. If used as a counter-attack against some prior complaint made by another interlocutor of ones absence, I havent seen may be treated as new which includes the thematic grammatical subject I.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- All About Subordinate ClausesDocument108 pagesAll About Subordinate Clauseshạnh hoàngPas encore d'évaluation

- Phrases and ClausesDocument29 pagesPhrases and ClausesArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Open Office Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesOpen Office Lesson PlancgrubichPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of Citizen KaneDocument5 pagesAnalysis of Citizen KaneRaees Ali Yar100% (1)

- Review Related LiteratureDocument3 pagesReview Related LiteratureSenpai Yat0% (1)

- English Morphology 2Document33 pagesEnglish Morphology 2M Qois ThonthowiPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample For Problem Sets For Syntax A Generative Introduction 3rd Edition by CarnieDocument8 pagesSample For Problem Sets For Syntax A Generative Introduction 3rd Edition by Carniehadi farzinPas encore d'évaluation

- File 13 UNIT 10Document25 pagesFile 13 UNIT 10Alina SeredynskaPas encore d'évaluation

- EuphemismDocument39 pagesEuphemismbbyk11767% (3)

- Lesson Plan G9Document3 pagesLesson Plan G9TaTa AcusarPas encore d'évaluation

- Theory Final (Alll Topics)Document19 pagesTheory Final (Alll Topics)Misha TeslenkoPas encore d'évaluation

- The 11 Laws of Likability SummaryDocument6 pagesThe 11 Laws of Likability SummaryChandra Clark100% (2)

- 1.0.1 Imaginative Vs Technical FinalDocument25 pages1.0.1 Imaginative Vs Technical Finalmadilag nPas encore d'évaluation

- Readingwriting - Week 5 7Document12 pagesReadingwriting - Week 5 7Errah Jane RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Saussure's Structural LinguisticsDocument10 pagesSaussure's Structural LinguisticsHerpert ApthercerPas encore d'évaluation

- Leadership & Conflict Management A Review of The Literature PDFDocument9 pagesLeadership & Conflict Management A Review of The Literature PDFali100% (1)

- Phrase Structure Rules & Transformations RuleDocument33 pagesPhrase Structure Rules & Transformations RuleUmaiy UmaiyraPas encore d'évaluation

- The Problem of Polysemy in The English LanguageDocument41 pagesThe Problem of Polysemy in The English LanguageOgnyan Obretenov100% (2)

- OJTREPORT2Document6 pagesOJTREPORT2Maricris ConcepcionPas encore d'évaluation

- The PassiveDocument58 pagesThe PassiveCronicile AnonymeiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Engl Get-Passive in Spoken DiscourseDocument18 pagesThe Engl Get-Passive in Spoken DiscourseBisera DalcheskaPas encore d'évaluation

- Get Be PasivesDocument8 pagesGet Be PasivesNerea GuibPas encore d'évaluation

- Theta Roles and Thematic Relations PDFDocument4 pagesTheta Roles and Thematic Relations PDFPedagógico Los OlivosPas encore d'évaluation

- Lexical and Grammatical TaransformationsDocument10 pagesLexical and Grammatical TaransformationsAlisa SayPas encore d'évaluation

- Semantics: Semantics (from Ancient Greek: σημαντικός sēmantikós)Document8 pagesSemantics: Semantics (from Ancient Greek: σημαντικός sēmantikós)Ahmad FaisalPas encore d'évaluation

- Charles DickensDocument21 pagesCharles DickensAlena BesirevicPas encore d'évaluation

- Ordinary Subject in A Simple Catenative Construction With To-Infinitivals Verb: AskDocument10 pagesOrdinary Subject in A Simple Catenative Construction With To-Infinitivals Verb: AskJelena SimsPas encore d'évaluation

- Wang (2010) Classification and SLA Studies of Passive VoiceDocument5 pagesWang (2010) Classification and SLA Studies of Passive VoiceEdward FungPas encore d'évaluation

- Polite Request in English and Arabic PDFDocument8 pagesPolite Request in English and Arabic PDFAhmad Law NovachronoPas encore d'évaluation

- Lexico-Syntactical Expressive Means and Stylistic DevicesDocument5 pagesLexico-Syntactical Expressive Means and Stylistic DevicesНастя МаксимоваPas encore d'évaluation

- Clause PatternsDocument11 pagesClause PatternsGeorgiana PuteanuPas encore d'évaluation

- SLA SkriptaDocument22 pagesSLA SkriptaAnđela AračićPas encore d'évaluation

- 09 - Chapter 3 PDFDocument27 pages09 - Chapter 3 PDFPintu BaralPas encore d'évaluation

- The Study of Language in Its Socio-Cultural ContextDocument7 pagesThe Study of Language in Its Socio-Cultural ContextMina ShinyPas encore d'évaluation

- Clause Complex SFLDocument4 pagesClause Complex SFLMuhammad UsmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Jasmina MilicevicDocument17 pagesJasmina MilicevicAzura W. Zaki100% (1)

- Stative and Dynamic VerbsDocument6 pagesStative and Dynamic VerbsАнђелка Гемовић100% (1)

- Defining and Non-Defining Relative Clauses: LevelDocument11 pagesDefining and Non-Defining Relative Clauses: LevelMaria SolPas encore d'évaluation

- Syntactic AnalysisDocument21 pagesSyntactic Analysissandrago75Pas encore d'évaluation

- IC AnalysisDocument4 pagesIC AnalysisMd.Rabiul IslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Catford TheoryDocument17 pagesCatford TheoryThaoanh NguyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Levels of AnalysisDocument44 pagesLevels of AnalysisRihamPas encore d'évaluation

- Semantic Roles of Clause ElementsDocument3 pagesSemantic Roles of Clause Elementsaquiles borgonovoPas encore d'évaluation

- X Bar TheoryDocument5 pagesX Bar TheoryPatrycja KliszewskaPas encore d'évaluation

- Nominal Categories in English. Theory and Practice - NR Pag - MijlocDocument320 pagesNominal Categories in English. Theory and Practice - NR Pag - MijlocVera Stefi100% (1)

- Pomagalo ComDocument15 pagesPomagalo ComKPAC333Pas encore d'évaluation

- THE Relationship Between Case AND AgreementDocument25 pagesTHE Relationship Between Case AND AgreementAnonymous R99uDjYPas encore d'évaluation

- ShiftsDocument18 pagesShiftsMAYS ShakerPas encore d'évaluation

- Descriptive Translation StudiesDocument14 pagesDescriptive Translation StudiesMohammed RashwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Semantics: Theory of SemanticDocument3 pagesSemantics: Theory of Semanticines sitompulPas encore d'évaluation

- Wuthering HeightsDocument5 pagesWuthering HeightsPetruta IordachePas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 4: Head, Complements, and Modifiers: Jong-Bok Kim & Peter Sells Jongbok@khu - Ac.kr, Sells@stanford - EduDocument47 pagesChapter 4: Head, Complements, and Modifiers: Jong-Bok Kim & Peter Sells Jongbok@khu - Ac.kr, Sells@stanford - EduNARAPas encore d'évaluation

- The Passive VoiceDocument12 pagesThe Passive VoicePetar JangelovskiPas encore d'évaluation

- Mona Baker - Contextualization in Trans PDFDocument17 pagesMona Baker - Contextualization in Trans PDFBianca Emanuela LazarPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Constituent Structure PDFDocument32 pages2 Constituent Structure PDFemman leonardo67% (3)

- H Ovement: Question That We Looked at in The Chapter On Head-MovementDocument38 pagesH Ovement: Question That We Looked at in The Chapter On Head-MovementThatha Baptista0% (1)

- 7th Chapter Part 2Document8 pages7th Chapter Part 2Samar SaadPas encore d'évaluation

- Syntactical - Devices 2Document34 pagesSyntactical - Devices 2Olga SmochinPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 5 - Theme and RhemeDocument29 pagesChapter 5 - Theme and RhemeIndah Gustri RahayuPas encore d'évaluation

- Department of EnglishDocument3 pagesDepartment of EnglishMuhammad Ishaq100% (1)

- Yule SyntaxDocument10 pagesYule SyntaxquincydegraciPas encore d'évaluation

- Derivational MorphemesDocument10 pagesDerivational Morphemesdevy0% (1)

- Syntactical Stylistic DevicesDocument3 pagesSyntactical Stylistic Devicesсаша синявскаяPas encore d'évaluation

- English Metalanguage ListDocument13 pagesEnglish Metalanguage ListAngus DelaneyPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Linguistic AnalysisDocument2 pagesWhat Is Linguistic AnalysisOlga SmochinPas encore d'évaluation

- Randal Whitman Teaching The Article in EnglishDocument11 pagesRandal Whitman Teaching The Article in EnglishdooblahPas encore d'évaluation

- Anglais ST2 AdouiDocument7 pagesAnglais ST2 AdouiŘãýãńë BëłPas encore d'évaluation

- Grammatical Analysis: ClauseDocument9 pagesGrammatical Analysis: ClauseVindy YusoviPas encore d'évaluation

- Workshop Using PhotographsDocument96 pagesWorkshop Using Photographsbbyk117Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tran Huong Quynh ProshowDocument9 pagesTran Huong Quynh Proshowbbyk117Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lang Learning and Technology - v17n3Document231 pagesLang Learning and Technology - v17n3bbyk117Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hangman - MusicDocument5 pagesHangman - Musicbbyk117Pas encore d'évaluation

- English InversionDocument1 pageEnglish Inversionbbyk117Pas encore d'évaluation

- Engineering Management ReviewerDocument14 pagesEngineering Management ReviewerAdrian RebambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Technology Vision Mission StatementDocument3 pagesTechnology Vision Mission StatementMichael King50% (2)

- Candidate Evidence FormDocument4 pagesCandidate Evidence Formapi-304926018Pas encore d'évaluation

- Storyboard Nefike GundenDocument12 pagesStoryboard Nefike Gundenapi-510845161Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1st Conditional Lesson Plan PDF FreeDocument3 pages1st Conditional Lesson Plan PDF FreepkmPas encore d'évaluation

- Machine Learning AlgorithmsDocument10 pagesMachine Learning AlgorithmsAshwin MPas encore d'évaluation

- Engaging Kids During Summer VacationDocument4 pagesEngaging Kids During Summer VacationTony 11StarkPas encore d'évaluation

- Resume For WeeblyDocument2 pagesResume For Weeblyapi-248810691Pas encore d'évaluation

- 08 - Chapter 3Document28 pages08 - Chapter 3Amrita AwasthiPas encore d'évaluation

- Research PaperDocument8 pagesResearch Paperapi-509848173Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pdevt Module 1 Knowing OneselfDocument7 pagesPdevt Module 1 Knowing OneselfDuckyHDPas encore d'évaluation

- Innate Behavior in InfantsDocument3 pagesInnate Behavior in InfantsSelvarani Abraham JohnPas encore d'évaluation

- MUET Speaking Task A Individual PresentaDocument4 pagesMUET Speaking Task A Individual PresentaMike NgPas encore d'évaluation

- Dermatoglyphics Multiple Intelligences Test (Dmit) ReportDocument77 pagesDermatoglyphics Multiple Intelligences Test (Dmit) ReportRaman AwasthiPas encore d'évaluation

- An Evaluation of The Comprehensiveness of The BSC Honours in Psychology Degree Offered at Zimbabwe Open University (ZOU)Document8 pagesAn Evaluation of The Comprehensiveness of The BSC Honours in Psychology Degree Offered at Zimbabwe Open University (ZOU)IOSRjournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Workshops?Document18 pagesWhy Workshops?AcornPas encore d'évaluation

- Content Based Instruction and SyllabusDocument21 pagesContent Based Instruction and SyllabussarowarPas encore d'évaluation

- Issues On Human Development: BY: Marvin Rotas PayabyabDocument16 pagesIssues On Human Development: BY: Marvin Rotas PayabyabTeacher BhingPas encore d'évaluation

- Giao An Tieng Anh Lop 12 Moi Thi Diem Tron BoDocument246 pagesGiao An Tieng Anh Lop 12 Moi Thi Diem Tron BoNguyen Huyen MinhPas encore d'évaluation

- GE4 - Week 1Document8 pagesGE4 - Week 1Cyrille Reyes LayagPas encore d'évaluation

- FD Midterm ExamDocument6 pagesFD Midterm ExamRocky Christopher FajardoPas encore d'évaluation

- Multiple Intelligences: Howard Gardner's Eight IntelligencesDocument4 pagesMultiple Intelligences: Howard Gardner's Eight Intelligencesschool workPas encore d'évaluation

- Transference and Counter-TransferenceDocument5 pagesTransference and Counter-TransferenceAlex S. EspinozaPas encore d'évaluation