Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Kant's Theory of Right

Transféré par

Xs SarahDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Kant's Theory of Right

Transféré par

Xs SarahDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Sarah Saud Fatmi Farah Zainal

Business ethics theories related to norm theory include Kantian ethical principles. These principles were developed by a Russian philosopher and theorist who proposed that ethical guidelines should speak to humanity as a collaborative group. Business ethics theories based on Kant's philosophy should treat humans as ends rather than as means. In other words, when developing a code of conduct, an individual should not use others to serve his own purpose or advantage.

Kantian ethics is another theory of "how one should act" however it differs from the utilitarian theory in a sense that it focuses more on the actual action and the morality of that action as opposed to the consequence of that action. This theory implies that as long as you act in a moral way then the consequences of your actions don't matter. Immoral actions include lying and using people as means to an end.

http://wiki.answers.com/Q/What_is_kantian_ethics#ixzz1mODZW0rv

Kants theory is an example of a deontological moral theoryaccording to these theories, the rightness or wrongness of actions does not depend on their consequences but on whether they fulfill our duty. Kant believed that there was a supreme principle of morality, and he referred to it as The Categorical Imperative. The CI determines what our moral duties are.

http://www.csus.edu/indiv/g/gaskilld/ethics/Kantian%20Ethics.htm

The basic idea: Kant argues that a person is good or bad depending on the motivation of their actions and not on the goodness of the consequences of those actions. By "motivation" I mean what caused you to do the action (i.e., your reason for doing it). Kant argues that one can have moral worth (i.e., be a good person) only if one is motivated by morality. In other words, if a person's emotions or desires cause them to do something, then that action cannot give them moral worth.

Why motivation is what matters: Imagine that I win the lottery and I'm wondering what to do with the money. I look around for what would be the most fun to do with it: buy a yacht, travel in first class around the world, get that knee operation, etc.. I decide that what would be really fun is to give the money to charity and to enjoy that special feeling you get from making people happy, so I give all my lottery money away. According to Kant, I am not a morally worthy person because I did this, after all I just did whatever I thought would be the most fun and there is nothing admirable about such a selfish pursuit. It was just lucky for those charities that I thought giving away money was fun. Moral worth only comes when you do something because you know that it is your duty and you would do it regardless of whether you liked it.

Why consequences don't matter: A reason why Kant is not concerned with consequences can be seen in the following example. Imagine two people out together drinking at a bar late one night, and each of them decides to drive home very drunk. They drive in different directions through the middle of nowhere. One of them encounters no one on the road, and so gets home without incident regardless of totally reckless driving. The other drunk is not so lucky and encounters someone walking at night, and kills the pedestrian with the car. Kant would argue that based on these actions both drunks are equally bad, and the fact that one person got lucky does not make them any better than the other drunk. After all, they both made the same choices, and nothing within either one's control had anything to do with the difference in their actions. The same reasoning applies to people who act for the right reasons. If both people act for the right reasons, then both are morally worthy, even if the actions of one of them happen to lead to bad consequences by bad luck.

The wrong interpretation: Consider the case described above about the lottery winner giving to charity. Imagine that he gives to a charity and he intends to save hundreds of starving children in a remote village. The food arrives in the village but a group of rebels finds out that they have food, and they come to steal the food and end up killing all the children in the village and the adults too. The intended consequence of feeding starving children was good, and the actual consequences were bad. Kant is not saying that we should look at the intended consequences in order to make a moral evaluation. Kant is claiming that regardless of intended or actual consequences, moral worth is properly assessed by looking at the motivation of the action, which may be selfish even if the intended consequences are good.

Kant does not forbid happiness: A careful reader may notice that in the example above one of the selfish person's intended consequences is to make himself happy, and so it might seem to be that intended consequences do matter. One might think Kant is claiming that if one of my intentions is to make myself happy, that my action is not worthy. This is a mistake. The consequence of making myself happy is a good consequence, even according to Kant. Kant clearly thinks that people being happy is a good thing. There is nothing wrong with doing something with an intended consequence of making yourself happy, that is not selfishness. You can get moral worth doing things that you enjoy, but the reason you are doing them cannot be that you enjoy them, the reason must be that they are required by duty. Also, there is a tendency to think that Kant says it is always wrong to do something that just causes your own happiness, like buying an ice cream cone. This is not the case. Kant thinks that you ought to do things to make yourself happy as long as you make sure that they are not immoral (i.e., contrary to duty), and that you would refrain from doing them if they were immoral. Getting ice cream is not immoral, and so you can go ahead and do it. Doing it will not make you a morally worthy person, but it won't make you a bad person either. Many actions which are permissible but not required by duty are neutral in this way.

Summary: According to Kant a good person is someone who always does their duty because it is their duty. It is fine if they enjoy doing it, but it must be the case that they would do it even if they did not enjoy it. The overall theme is that to be a good person you must be good for goodness sake.

Kants view is that lying is always wrong. His argument for this is summarized by James Rachels as follows: (1) We should do only those actions that conform to rules that we could will be adopted universally. (2) If we were to lie, we would be following the rule It is permissible to lie. (3) This rule could not be adopted universally, because it would be self-defeating: people would stop believing one another, and then it would do no good to lie. (4) Therefore, we should not lie.

The problem with this argument is that we can lie without simply following the rule It is permissible to lie. Instead, we might be following a rule that pertains only to specific circumstances, like It is permissible to lie when doing so will save a life. This rule can be made a universal law without contradiction. After all, it is not as though people would stop believing each other simply because it is known that people lie when doing so will save lives. For one thing, that situation rarely comes up people could still be telling the truth almost all of the time. Even the taking of human life could be justified under certain circumstances. Take self-defense, for example. There appears to be nothing problematic with the rule It is permissible to kill when doing so is the only available means of defense against an attacker.

It is not necessary to interpret Kants theory as prohibiting lying in all circumstances (as Kant did). Maxims (and the universal laws that result from them) can be specified in a way that reflects all of the relevant features of the situation. Consider the case of the Inquiring Murderer (as described in the text). Suppose that you are in that situation and you lie to the murderer. Instead of understanding the universalized maxim as Everyone Always lies we can understand it as Everyone always lies in order to protect innocents from stalkers. This maxim seems to pass the test of the categorical imperative. Unfortunately, complicated maxims make Kants theory becomes more difficult to understand and apply.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- InvictusDocument6 pagesInvictusHaley BoscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Outdoor Education 2ndyearDocument12 pagesOutdoor Education 2ndyearZedy GullesPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Aesthetics by Ellen Miller-GROUP 1Document17 pagesIntroduction To Aesthetics by Ellen Miller-GROUP 1JubilynecoPas encore d'évaluation

- Schools of ThoughtDocument3 pagesSchools of ThoughtRomalyn Galingan100% (1)

- Purposive CommunicationDocument3 pagesPurposive CommunicationLeila Marie MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- LearningDocument14 pagesLearningKewkew AzilearPas encore d'évaluation

- Geethic The Value of Philosophy by Bertrand RussellDocument2 pagesGeethic The Value of Philosophy by Bertrand Russellsam tPas encore d'évaluation

- Jacques-Louis David ReflectionDocument2 pagesJacques-Louis David Reflectionluvsport8100% (2)

- Purdue OWL Literary CriticismDocument24 pagesPurdue OWL Literary CriticismFaezah Ismail100% (1)

- Saeed Sentence Relation and Truth (Summary)Document11 pagesSaeed Sentence Relation and Truth (Summary)Mohammad Hassan100% (1)

- VDA Volume Assessment of Quality Management Methods Guideline 1st Edition November 2017 Online-DocumentDocument36 pagesVDA Volume Assessment of Quality Management Methods Guideline 1st Edition November 2017 Online-DocumentR JPas encore d'évaluation

- Moral Political Approach EDITED FINALDocument4 pagesMoral Political Approach EDITED FINALCHARLIES CutiesPas encore d'évaluation

- Advantages and Disadvantages of The Five Teaching StrategiesDocument4 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of The Five Teaching StrategiesCyrill Gabunilas FaustoPas encore d'évaluation

- Denotation and ConnotationDocument25 pagesDenotation and Connotationmadutza_auroraPas encore d'évaluation

- The Relationship Between School and Society - Part II - Conflict T PDFDocument3 pagesThe Relationship Between School and Society - Part II - Conflict T PDFtahreem rashidPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophical Foundations of EducationDocument4 pagesPhilosophical Foundations of EducationRextan GonzalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Academic Self Concept Scale For Adolescents Development Reliability and Validity of ASCSDocument7 pagesAcademic Self Concept Scale For Adolescents Development Reliability and Validity of ASCSAnupam Kalpana GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- J.K. Rowling's BiographyDocument4 pagesJ.K. Rowling's Biographyjosue hernaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Brief History of Russian FormalismDocument9 pagesA Brief History of Russian FormalismpanparasPas encore d'évaluation

- Ugly ArtDocument22 pagesUgly ArtSandeiana GracePas encore d'évaluation

- Differences Between Idealism and RealismDocument9 pagesDifferences Between Idealism and RealismAyesha AshrafPas encore d'évaluation

- Prof Ed 10 Module 1 Preliminaty TopicsDocument4 pagesProf Ed 10 Module 1 Preliminaty TopicsRhina Mae ArguezaPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding The Elements of PoetryDocument10 pagesUnderstanding The Elements of PoetryHiraeth AlejandroPas encore d'évaluation

- The Visitation of The GodsDocument18 pagesThe Visitation of The GodsJae Anne MagsanayPas encore d'évaluation

- Kohlbergs Stages of Moral DevelopmentDocument20 pagesKohlbergs Stages of Moral DevelopmentArunita Padhi SarangiPas encore d'évaluation

- Reason and ImpartialityDocument19 pagesReason and ImpartialityHannahGraceD Cano100% (1)

- Name: Shama Arshad I.D: S2020381016 Logical Reasoning Section: Sir Assignment What Is Philosophy? PhilosophyDocument3 pagesName: Shama Arshad I.D: S2020381016 Logical Reasoning Section: Sir Assignment What Is Philosophy? PhilosophyAhmed AnjumPas encore d'évaluation

- Gestalt PsychologyDocument32 pagesGestalt PsychologyCarla JoycePas encore d'évaluation

- Critical LiteracyDocument3 pagesCritical LiteracyJaysonCruzPas encore d'évaluation

- LET REVIEWER Literary CriticismDocument13 pagesLET REVIEWER Literary CriticismGian Nathaniel Martin ManahanPas encore d'évaluation

- 26 Subjectivity and Objectivity in Literary StylisticsDocument19 pages26 Subjectivity and Objectivity in Literary StylisticsAwais100% (1)

- BAJAR, Pheodor Alfred D. 10/09/2020 PT 1-3 Sir Jed AbatayoDocument2 pagesBAJAR, Pheodor Alfred D. 10/09/2020 PT 1-3 Sir Jed AbatayoAlfred Bajar0% (1)

- Foundationofeducation1 171005183006Document54 pagesFoundationofeducation1 171005183006Rainiel Victor M. CrisologoPas encore d'évaluation

- The 5 Law of Gestalt PsychologyDocument4 pagesThe 5 Law of Gestalt PsychologyExcel Joy MarticioPas encore d'évaluation

- Chomsky's Cognitive TheoryDocument7 pagesChomsky's Cognitive TheoryCamCatimpo100% (1)

- Ethics PDFDocument19 pagesEthics PDFJANELLE AYRA PARAISOPas encore d'évaluation

- My Report in BehaviorismDocument14 pagesMy Report in BehaviorismDorepePas encore d'évaluation

- Formalistic Approach PDFDocument21 pagesFormalistic Approach PDFCharmnette CalatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Systematic and Nonsystematic Observation - MarasiganDocument1 pageSystematic and Nonsystematic Observation - MarasiganAnabelle MagbilangPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethics 1Document27 pagesEthics 1Jezz Villadiego0% (1)

- Charles Wright MillsDocument11 pagesCharles Wright MillsEmmanuel S. CaliwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethics - Module 3Document20 pagesEthics - Module 3Dale CalicaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 - Course American PostmodernismDocument4 pages2 - Course American PostmodernismClaudia Grigore BubuPas encore d'évaluation

- DeontologyDocument21 pagesDeontologyLyza PacibePas encore d'évaluation

- FieldtripDocument17 pagesFieldtripfrederickPas encore d'évaluation

- Existentialism: Philosophy of EducationDocument20 pagesExistentialism: Philosophy of EducationMaryKtine SagucomPas encore d'évaluation

- LIT - Odysseus (Opinion)Document4 pagesLIT - Odysseus (Opinion)rodjanyogPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy EducationDocument35 pagesPhilosophy EducationroxannePas encore d'évaluation

- What Is PhilosophyDocument14 pagesWhat Is PhilosophyCyril MoniquePas encore d'évaluation

- Zahavi 1998 - The Fracture in Self AwarenessDocument15 pagesZahavi 1998 - The Fracture in Self AwarenessPhilip Reynor Jr.100% (1)

- Types of LiteratureDocument4 pagesTypes of LiteraturePatricia SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Flavel LDocument9 pagesFlavel LKristina KljucaricPas encore d'évaluation

- (Lect03) - Logical EmpiricismDocument13 pages(Lect03) - Logical EmpiricismKai ErlenbuschPas encore d'évaluation

- Literary Theory and Criticism QQDocument14 pagesLiterary Theory and Criticism QQARIF KHANPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychology Before 1900Document9 pagesPsychology Before 1900Angely Ricardo LozanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1Document13 pagesChapter 1Chindy Yulia PermatasariPas encore d'évaluation

- The Literature of ExplorationDocument2 pagesThe Literature of ExplorationPolynne Espineda DiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Immanuel Kant: 1A2 - Group3Document23 pagesImmanuel Kant: 1A2 - Group3Kenneth Dalton Peji FloraPas encore d'évaluation

- GE 8 - Art Appreciation Module 11 & 12Document6 pagesGE 8 - Art Appreciation Module 11 & 12Paula Jane CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- StructuralismDocument4 pagesStructuralismKhurram ShahzadPas encore d'évaluation

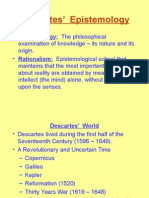

- Descartes' EpistemologyDocument21 pagesDescartes' EpistemologyMEOW41Pas encore d'évaluation

- Kantian Ethics: Their Consequences But On Whether They Fulfill Our DutyDocument14 pagesKantian Ethics: Their Consequences But On Whether They Fulfill Our DutyMahnoor SaleemPas encore d'évaluation

- Aa DistriDocument3 pagesAa Distriakosiminda143Pas encore d'évaluation

- Attitude of Tribal and Non Tribal Students Towards ModernizationDocument9 pagesAttitude of Tribal and Non Tribal Students Towards ModernizationAnonymous CwJeBCAXpPas encore d'évaluation

- Proposal For A Working Procedure To Accurately Exchange Existing and New Calculated Protection Settings Between A TSO and Consulting CompaniesDocument9 pagesProposal For A Working Procedure To Accurately Exchange Existing and New Calculated Protection Settings Between A TSO and Consulting CompaniesanonymPas encore d'évaluation

- OSX ExpoDocument13 pagesOSX ExpoxolilevPas encore d'évaluation

- Install NoteDocument1 pageInstall NoteJose Ramon RozasPas encore d'évaluation

- Solutions - HW 3, 4Document5 pagesSolutions - HW 3, 4batuhany90Pas encore d'évaluation

- Heart Attack Detection ReportDocument67 pagesHeart Attack Detection ReportAkhil TejaPas encore d'évaluation

- Norm ANSI PDFDocument1 pageNorm ANSI PDFAbdul Quddus Mat IsaPas encore d'évaluation

- GRADE 302: Element Content (%)Document3 pagesGRADE 302: Element Content (%)Shashank Saxena100% (1)

- The Elder Scrolls V Skyrim - New Lands Mod TutorialDocument1 175 pagesThe Elder Scrolls V Skyrim - New Lands Mod TutorialJonx0rPas encore d'évaluation

- Grade 8 Science Text Book 61fb9947be91fDocument289 pagesGrade 8 Science Text Book 61fb9947be91fNadarajah PragatheeswarPas encore d'évaluation

- 1980 - William Golding - Rites of PassageDocument161 pages1980 - William Golding - Rites of PassageZi Knight100% (1)

- LG) Pc-Ii Formulation of Waste Management PlansDocument25 pagesLG) Pc-Ii Formulation of Waste Management PlansAhmed ButtPas encore d'évaluation

- Microcal P20Document2 pagesMicrocal P20ctmtectrolPas encore d'évaluation

- E WiLES 2021 - BroucherDocument1 pageE WiLES 2021 - BroucherAshish HingnekarPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 Hu Spence Why Globalization Stalled and How To Restart ItDocument11 pages2017 Hu Spence Why Globalization Stalled and How To Restart Itmilan_ig81Pas encore d'évaluation

- Project - Dreambox Remote Video StreamingDocument5 pagesProject - Dreambox Remote Video StreamingIonut CristianPas encore d'évaluation

- Cambridge IGCSE: PHYSICS 0625/62Document12 pagesCambridge IGCSE: PHYSICS 0625/62EffPas encore d'évaluation

- Lords of ChaosDocument249 pagesLords of ChaosBill Anderson67% (3)

- NRNP PRAC 6665 and 6675 Focused SOAP Note ExemplarDocument6 pagesNRNP PRAC 6665 and 6675 Focused SOAP Note ExemplarLogan ZaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Angles, Bearings and AzimuthDocument10 pagesAngles, Bearings and AzimuthMarc Dared CagaoanPas encore d'évaluation

- Poster PresentationDocument3 pagesPoster PresentationNipun RavalPas encore d'évaluation

- JurnalDocument12 pagesJurnalSandy Ronny PurbaPas encore d'évaluation

- Annual Report 2022 2Document48 pagesAnnual Report 2022 2Dejan ReljinPas encore d'évaluation

- Property Case Digest DonationDocument13 pagesProperty Case Digest DonationJesselle Maminta100% (1)

- Chapter 17 Study Guide: VideoDocument7 pagesChapter 17 Study Guide: VideoMruffy DaysPas encore d'évaluation

- Speaking Quý 1 2024Document43 pagesSpeaking Quý 1 2024Khang HoàngPas encore d'évaluation

- Homelite 18V Hedge Trimmer - UT31840 - Users ManualDocument18 pagesHomelite 18V Hedge Trimmer - UT31840 - Users ManualgunterivPas encore d'évaluation