Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Delivering More Effective Stormwater Management in The UK and Europe

Delivering More Effective Stormwater Management in The UK and Europe

Transféré par

coutohahaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- 5-Calcul D'un Réseau D'eaux Usées (Corrigé)Document4 pages5-Calcul D'un Réseau D'eaux Usées (Corrigé)Mamadou Niang71% (7)

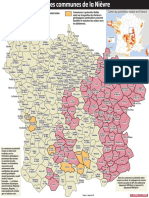

- Carte Du Potentiel Radon Des Communes de La NièvreDocument1 pageCarte Du Potentiel Radon Des Communes de La NièvreAmélie JamesPas encore d'évaluation

- Examen Final B1.1Document5 pagesExamen Final B1.1Jose Andres Jaimes PicoPas encore d'évaluation

- Par ExxDocument96 pagesPar Exxva15la15Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cours HDR Sommaire 23 Mai 2015Document69 pagesCours HDR Sommaire 23 Mai 2015deziri mohamedPas encore d'évaluation

- Fiche EstimativeDocument2 pagesFiche EstimativeAbdelaly JabbadPas encore d'évaluation

- Math TescoDocument4 pagesMath TescoYoussouf DiakitéPas encore d'évaluation

- Chimie-TP3 Mesure Du PH de Solutions-CorrDocument2 pagesChimie-TP3 Mesure Du PH de Solutions-CorrChartier JulienPas encore d'évaluation

- Rapport SéparateurDocument7 pagesRapport Séparateursi parPas encore d'évaluation

- L'industrie de L'huile D'oliveDocument8 pagesL'industrie de L'huile D'oliveaminesa100% (1)

- Schematique HydrauliqueDocument1 pageSchematique HydrauliquehassenbbPas encore d'évaluation

- CP ADEME-DTT Charte Éco MobiliteDocument2 pagesCP ADEME-DTT Charte Éco MobiliteFred AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Boue Nord CamDocument4 pagesBoue Nord CamACIDPas encore d'évaluation

- Guide Branchements ONEPDocument35 pagesGuide Branchements ONEPSlimaneZarga100% (1)

- Expose Audrey Et Clara DiffuserDocument4 pagesExpose Audrey Et Clara Diffuser7000dyvezahxoPas encore d'évaluation

- Energie Evaluation Environnementale PDFDocument124 pagesEnergie Evaluation Environnementale PDFSissy carburePas encore d'évaluation

- Unité Sauvons La Planète PDFDocument12 pagesUnité Sauvons La Planète PDFSara RenovellPas encore d'évaluation

- 21 255 266Document12 pages21 255 266Mecif BrahimPas encore d'évaluation

- Session 9.biomass Exercise - FR (UNSD)Document5 pagesSession 9.biomass Exercise - FR (UNSD)Imane EmyPas encore d'évaluation

- M2P Hydrogeol TD1 2004 PDFDocument2 pagesM2P Hydrogeol TD1 2004 PDFKhaoula ZefanePas encore d'évaluation

- Etude D'impactDocument83 pagesEtude D'impactIbti100% (1)

- 1 Labo TP2Document12 pages1 Labo TP2Yahia BobPas encore d'évaluation

- 08 Hochbau Anwendung FRDocument57 pages08 Hochbau Anwendung FRNuno TomásPas encore d'évaluation

Delivering More Effective Stormwater Management in The UK and Europe

Delivering More Effective Stormwater Management in The UK and Europe

Transféré par

coutohahaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Delivering More Effective Stormwater Management in The UK and Europe

Delivering More Effective Stormwater Management in The UK and Europe

Transféré par

coutohahaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

SESSION 8.

Delivering more effective stormwater

management in the UK and Europe – lessons

from the Clean Water Act in America

Pour une gestion plus efficace des eaux pluviales au Royaume Uni

et en Europe : Enseignements du "clean water act" en Amérique.

Prof Richard Ashley 1, Jeremy Jones 2, Stuart Ramella 3, David

Schofield 4, Richard Munden 5, Kate Zabatis 6, Alan Rafelt 7, Alex

Stephenson 8, Dr Ian Pallett 9.

1

Pennine Water Group, University of Sheffield, Mappin Street, Sheffield, S1 3JD.

R.Ashley@sheffield.ac.uk.

2

Integrated Urban Drainage Steering Group, c/o Wastewater Strategy Manager, CWW,

Pentwyn Road, Nelson, Treharris, CF46 6LY. jeremy.jones@ntlworld.com

3

Polypipe Civils Ltd, Union Works, Loughborough, Leicestershire,LE11 5RE.

Stuart.Ramella@Polypipe.com.

4

Arup, The Arup Campus, Blythe Gate, Blythe Valley Park, Solihull, West Midlands, B90

8AE david.schofield@arup.com

5

COPA Ltd., Crest Industrial Estate, Marden, Tonbridge, Kent, TN12 9QJ

6

United Utilities North West, Thirlmere House, Lingley Mere Business Park, Great

Sankey, Warrington, Cheshire WA5 3LP. kate.zabatis@uuplc.co.uk

7

Environment Agency, Manley House, Kestrel Way, Exeter, Devon, EX2

LQ.alan.rafelt@environment-agency.gov.uk

8

Hydro International, Shearwater House, Clevedon Hall Estate, Victoria Road,

Clevedon, BS21 7RD. alex.stephenson@hydro-international.co.uk

9

British Water, 1 Queen Anne’s Gate, London SW1H 9BT,

ian.pallett@britishwater.co.uk

RESUME

Le CWA - Clean Water Act (programme Eau Pure Américain) mis en place aux Etats-

Unis dans les années 70 peut apporter des enseignements très utiles pour l'Europe.

Le CWA fût l'élément moteur pour l'amélioration des cours d'eau et autres milieux

aquatiques. Il a dû faire face aux même types de difficultés et opportunités que celles

rencontrées aujourd'hui en Europe lorsque l'on travaille sur les systèmes de gestion

des eaux pluviales. Par l'analyse des 30 années d'histoire du CWA, l'Europe devrait

être capable d'éviter une bonne partie des problèmes rencontrés aux Etats-Unis pour

maîtriser les rejets d'eaux pluviales afin d'améliorer la qualité de l'eau.

ABSTRACT

What is known as the Clean Water Act (CWA) in the USA, implemented in the early

1970s, can provide some useful lessons for Europe. The CWA has been the key

driver in cleaning up watercourses and other water bodies, has encountered a similar

range of difficulties and opportunities that are being found across Europe when

dealing with stormwater systems. By drawing on the 30 years of historical lessons

from the CWA, the EU should be able to avoid many of the problems encountered in

the USA for controlling stormwater discharges to deliver improvements in water

quality.

KEYWORDS

BMP, Clean Water Act, Floods Directive, Institutional factors, Legislation, LID, Priority

Hazardous Substances, Stormwater, SUDS, Water Framework Directive.

NOVATECH 2007 1697

SESSION 8.3

INTRODUCTION

Europe is required to implement the “good status” requirements of the Water

Framework Directive (WFD) by 2015 (Commission of the European Communities,

2000). This provides the European Community (EC) framework for the protection of

waters. The aim is to promote the sustainable use of water, while progressively

reducing or eliminating pollutants for the long-term protection and enhancement of the

aquatic environment. A new proposal for a Directive on the Assessment and

Management of Floods (Floods Directive) (Commission of the EC, 2006) sets out to

reduce and manage flood risk. The Floods Directive and measures taken to

implement it are to be closely linked to the implementation of the WFD. The EC

proposes to fully align the organisational and institutional aspects and timing between

the Directives, based on river basin districts defined in the WFD.

Particular challenges for stormwater management are two WFD ‘daughter’ Directives

in preparation. One concerns groundwater and the definition of good chemical quality,

and the other, the way in which the most polluting substances are handled, the

‘priority substances’ (PS) and the ‘priority hazardous substances’ (PHS); some of

which, such as nickel, are ubiquitous in stormwater. Notwithstanding the daughter

Directives, stormwater sewers and drains are known to convey significant pollutants

and need to be better controlled under the WFD; albeit such pollution being better

managed at source than in drains.

There are various forms of ownership and operation of the networks of combined or

separate drains and sewers across the EU that convey stormwater runoff (e.g.

Middlesex University, 2003; Mohajeri et al, 2003; Juuti & Katko, 2005). These may be

owned publicly or privately or be part of the network that is operated by sewerage

undertakers or municipalities. Similar extents of combined and separate sewers also

exist in the USA. Best Management Practices (BMPs) for the management of storm

water, are common in many countries worldwide, despite a lack of consistent

information on their performance even in the USA (Field et al, 2006). There is a

general belief that these systems are ‘more natural’ or ‘more sustainable’ than

conventional piped drainage and sewerage systems. At the very least BMPs usually

provide the means to simultaneously deliver water quality, quantity and amenity

benefits and are a major component in the delivery of clean-up of stormwater

discharges required under the Clean Water Act (CWA) in the USA.

There are clear parallels between the WFD and the CWA. The latter was

implemented in the early 1970s and has resulted in significant efforts to improve the

quality of America’s ‘impaired’ water bodies, much of which has included

improvements to stormwater management. US experience has demonstrated that the

use of BMPs and Low Impact Developments (LIDs) can be a much more cost-

effective way of ensuring protection to receiving waters than the traditional approach

of stormwater control using drains and sewers. In addition to separate storm

drainage, BMPs can also help to better manage the stormwater that is discharged

into combined sewers, by slowing down the rate of runoff, or even by removing these

inputs altogether.

There are similarities between the member States of the EC and the individual States

in the USA, although the Federal legislation and the main regulator the US

Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) have a more direct role in the

implementation of the CWA in the USA. There is no equivalent in the EU as each

member state is responsible for the implementation and policing of the WFD

requirements. This paper reports on an investigation of US practice in relation to

European practices and has concluded that there are a number of important lessons

and opportunities of relevance from US practice to better manage stormwater

in Europe.

1698 NOVATECH 2007

SESSION 8.3

THE MAIN IMPLICATIONS OF THE WFD FOR STORMWATER

MANAGEMENT

The WFD is an opportunity to ensure a consistent and integrated approach to the way

in which we currently manage water within defined river basin districts. The

establishment of the European 'priority list' of substances posing a threat to or via the

aquatic environment is significant. There are currently 33 priority substances on this

priority list (Official Journal of the EC, 2001; Commission of the EC, 2006a).

Estimates of the costs of compliance for the UK suggest some €9bn would be needed

to deal with these substances for the discharges from point sources alone. Even with

this level of investment, only some 70% of the PHS would actually be removed (Ross

et al, 2004). However, the 33 so far identified could be added to significantly in the

future and this may add additional treatment and financial burdens and possibly

require the development and installation of new technologies. Inevitably the Directive

will mean that some stormwater and other discharges to water bodies will be required

to cease or at the least have substantial treatment systems installed.

The precise standards to be attained to comply with the WFD are being set within and

by each member state. Ecosystems do not recognise state boundaries and hence

there has to be harmonisation especially across shared borders. Even in the UK the

approach to the implementation and adoption of proposals is likely to vary for each

constituent country, depending on present and proposed legislation and on policy

differences. It will also depend on the need for Ireland and the UK, as separate

Member States, to harmonise standards, where appropriate, within shared River

Basin Districts (UKTAG, 2006).

In addition to the WFD, the proposed Floods Directive seeks to provide maps and

flood risk management plans through a broad participatory process. The main

purpose of the draft Floods Directive is to set out a framework for the reduction of risk

to human health, the environment and economic activity associated with flooding.

THE CLEAN WATER ACT

Governance in the USA is exercised at a National or Federal level and also at a State

level, with Counties and Townships, and in some areas, Indigenous peoples (tribes)

having responsibilities and a degree of autonomy not typically seen in Europe. Much

of the clean up of water bodies in the USA has resulted from litigation by activists and

NGOs. This led to the enactment of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act

Amendments of 1972. This law became commonly known as the CWA. This gave the

Federal Agency and the EPA the authority to implement pollution control programmes

and continued requirements to set water quality standards for all contaminants in

surface waters, requiring a permit to discharge any pollutant from a point source into

navigable waters.

The National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) ‘MS4’: Municipal

Separate Storm Sewer Systems was developed to protect receiving waters from

contaminated stormwater discharges (Maestre et al, 2004). Initially the EPA believed

that the traditional end-of-pipe controls used for process discharges and treatment

works could not be used to control stormwater pollution. Stormwater regulations

(Phase I) were initially developed for large municipalities (>100,000 population) and

for certain industrial categories. Now Phase II of the stormwater permit programme

extends to all urban areas. The CWA provided the capability to implement stormwater

management plans at the regional level and was welcomed by planners; however, in

the late 1970s problems arose due to inadequate data and lack of technological

development. As a consequence, between 1978 and 1983, the USEPA conducted the

Nationwide Urban Runoff Programme (NURP) to determine water quality from

separate storm sewers for different land uses.

NOVATECH 2007 1699

SESSION 8.3

Starting in the late 1980s, efforts to address polluted runoff have increased

significantly. For ‘non-point’ runoff, voluntary programmes, including cost-sharing with

local landowners, are the key tool. For ‘wet weather point sources’ like urban storm

sewer systems and construction sites, a regulatory approach is now being employed.

Engagement of stakeholder groups in the development and implementation of

strategies for achieving and maintaining State water quality and other environmental

goals is another hallmark. Evolution of CWA programmes over the last decade has

included a shift to more holistic watershed-based strategies with equal emphasis on

protecting healthy waters and restoring those that are ‘impaired’.

States can be authorized to administer the NPDES program by EPA. An NPDES

programme has various components, including; Base Programme for municipal and

industrial trial facilities, Federal Facilities, General Permitting, Pretreatment

Programme and Biosolids. A State may receive EPA authorisation for one or more of

the NPDES Programme components.

The control of stormwater depends ultimately on the appropriateness of the local

municipality within the regulatory system. Whilst the granting of Permits is delegated

from EPA to State level this is often further delegated. In general, this usually reflects

the population of the area. Where populations are less dense, this authority would be

administered at County Level, and in sparsely populated areas would probably be

retained at State level.

Whilst it would appear that the regulations are disjointed, with some States still not

having yet achieved even Phase I of the CWA, let alone working towards Phase II,

which has a delivery date of 2008, this is inevitable given the flexibility in the

implementation process. The requirements of the CWA are implemented at site level

via the definition of Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) for impaired water bodies. A

TMDL is a calculation of the maximum amount of a pollutant that a water body can

receive and still meet pre-defined water quality standards, and an allocation of that

amount to the source of pollutants causing the impairment. The most common

reported impairments are: metals (19%); pathogens (13%); nutrients (9%); sediment

(8%) (TMDL website: www.epa.gov/owow/tmdl/).

The CWA establishes the water quality standards and TMDL programmes, this

requires that the jurisdictions establish priority rankings for waters on the lists and

develop TMDLs for these. Specific guidance is also provided on the mandatory public

outreach programme for which local towns would be responsible. This should focus

on educating the public about negative water quality impacts. In summary, it is

apparent that the regulatory practices from State to State are variable, but these are

appropriate to the locale which they serve. Usually provided the construction of the

stormwater systems receives the appropriate permits these will then be taken over

(adopted) by the municipality, county or state.

LESSONS FROM USA CONTROL OF STORMWATER PRACTICES

FOR EUROPE

Although the CWA has been the baseline for cleaning up the waters of the USA since

1972, progress has been slow, often achieved only through litigation and court orders.

The devolution of responsibilities for NPDES to State and local level, with some

retained by the EPA, has resulted in a complex and fragmented approach being

taken, albeit one in which local knowledge and priorities have established the main

goals for improving impaired waters and for which local community involvement has

been strong. Stormwater facilities are delivered and managed by a wide variety of

organisations, from municipalities to private contractors and the use of stormwater

utility companies is common.

1700 NOVATECH 2007

SESSION 8.3

A range of measures for the management and treatment of stormwater in the USA

are evident. These range from structural controls to ‘natural’ and equivalent ‘green’

systems. Early on in the development of the measures arising from the CWA and in

setting TMDLs, it was realised that the performance of BMPs in terms of water quality

could not be readily defined due to a lack of knowledge about their long term

performance (Field et al, 2006). Associated with this has been the accreditation of a

number of proprietary devices for the removal of specific pollutants. Unfortunately the

desire for a ‘universal’ treatment system for stormwater pollution control has also

resulted in the promotion of such systems and their utilisation, despite their inability to

provide ‘complete treatment’.

The CWA has a number of similarities to the WFD. However, the CWA has been

around for 30 years with a target for Phase II implementation of 2008. The WFD

echoes a lot of similar sentiments to the CWA but implementation is expected over a

much shorter and possibly unrealistic time frame. Many of the water quality standards

that are enforced in the EU have centered on the quality issues relating to

foul/combined sewer pollution. Surface water has heretofore not been subject to the

same degree of quality control (Middlesex University, 2003). Apart from the

imposition of petrol/oil interceptors when high levels of pollution are expected there is

little to be found for guidance on the form of treatment for stormwater. Some of the

requirements to remove pollutants from stormwater can be overly onerous under both

the CWA and WFD. Caution is required when it is expected that the removal of ‘all’ of

a certain ‘specified pollutant’ such as Cadmium or Nickel is possible or even desirable

economically, as some of these elements are naturally occurring and total removal is

not realistic other than through changes at source.

In the USA as well as the EU there is a move to new ‘more natural’ stormwater

management approaches, BMPs, LIDs, SUDS (sustainable drainage systems) and

‘source controls’. In some parts of the USA ‘natural’ stormwater systems, originally

defined as BMPs, have been in use for at least 50 years as an alternative to

traditional piped drains and sewers. There is therefore a long history of experience in

regulating, implementation and use. Inherent in these is the need for greater

engagement of all the actors involved. In the USA citizen involvement in the planning

of stormwater management via formal boards, informal citizen groups and other

activities is notably strong since it is a requirement under the CWA. Whilst this does

occur in the EU, such involvement is generally much weaker and gaining public

confidence and commitment to the better management of stormwater is therefore

often ineffective (e.g. for UK, see House of Lords, 2006).There are major

impediments to the use of these systems in many EU countries due to urban density,

regulatory inadequacies and institutional constraints. Elsewhere in the world, such as

in the USA, many of these barriers do not exist as institutional arrangements are

more flexible, although there are other challenges to be overcome. New ideas and

versatile systems are needed that will assist with particular applications in Europe,

such as high density housing, retrofitting to resolve existing problems and to meet the

requirements of the WFD.

US experience has shown that the incremental and localised small-scale

management of stormwater, such as: evapotranspiration techniques; green roofs;

water gardens and/or disconnecting existing inputs to major drainage systems can

collectively provide significant benefits to managing local and downstream water

quality and quantity. These approaches can also provide other benefits such as local

irrigation or opportunities for reuse.

It is apparent from US practice that there are considerable benefits from providing

greater incentives for the use of innovative stormwater management techniques.

These are most effective where the stormwater costs are clearly identifiable within

NOVATECH 2007 1701

SESSION 8.3

charging schemes. Incentives include charges (and discounts) based on directly

connected impervious areas. Clearly identifiable costs and discount or rebate

opportunities can aid in engaging each of the stakeholders. In many areas of the

USA separate stormwater utilities (municipal or private) deliver a service associated

with a defined income stream as above. These utilities also raise awareness of

stormwater, help identify better opportunities for innovative management and more

effectively engage all stakeholder groups.

Whole life performance and costing of stormwater systems is needed to include

construction, maintenance and the selection of the most appropriate sustainable

drainage systems (this may include piped systems). Ensuring effective design and

construction is challenging even in the USA and the lodging of developer payments

with the regulatory authorities before construction can ensure that good designs and

construction are actually delivered.

In the USA the CWA makes clear recommendations about education and community

participation. There is a need to build capacity (knowledge and competence) within

the stakeholder communities and also to help stakeholders understand/accept

innovatory approaches and technologies which may include the need to assume a

more responsible role. There are a wide variety of approaches to the adoption and

maintenance of BMPs in the USA, from municipal responsibility to individual

householders. Within a particular regulatory area there is a tendency to utilise one

single approach. It is apparent that stormwater systems should be adopted and

managed by a single appropriate agency within a local context. This may be a

separate stormwater utility (see above). In the EU adoption and maintenance is a

major challenge for local on-site systems and is linked to how these systems are

funded, which is not uniform across the community.

Notwithstanding recent efforts in the EU, there is a need to invest more in developing

and evaluating the long term performance of BMPs via clearly defined and

scientifically robust long-term monitoring. Protocols for monitoring defined from US

studies will help to define investigation programmes (e.g. Roesner et al, 2006). This

will require significant investment across the community and in member states and

should be recognised by regulators and others as essential for the development of

long-term and sustainable stormwater management systems. There is a need to

better understand the effectiveness of dispersed solutions to the management of

stormwater in a European wide context. Costs, risks and institutional barriers need to

be considered within a whole system performance context. Cross-regulatory and

institutional barriers arising due to the mixed management responsibility for

stormwater in many countries in the EU need to be exposed and eliminated where

stormwater disconnection is identified as the best option.

A separate and identifiable separate surface/storm water charge should be apparent

to bill payers as is done in many parts of the USA, in the same way that sewage and

water charges are usually identified. Alternatives available for stormwater system

users to e.g. disconnect, reuse, fit green roofs, should be made clear in information

available from regulators and sewerage service providers and others such as public

groups. This should be accompanied by clear indications of the financial support and

benefits (rebates) available for alternatives, along with educational programmes

aimed at building the capacity of householders, facilities managers and others to take

a more active role in local stormwater management. As the latter will not be in the

interests of any private sewerage undertakers, because it will lead to a reduction in

income, regulators will need to review the incentives to the undertakers to promote

these changes to current practice. The limited experience of BMPs and equivalent

systems worldwide means that there needs to be better arrangements in place to

1702 NOVATECH 2007

SESSION 8.3

ensure good design and construction. This requires the education and training of all

stakeholders, especially planners and building control officers.

CONCLUSION

The capacity to understand and deal effectively with stormwater within virtually all

stakeholder communities in Europe is limited. This is also true even in the USA,

although the CWA recognises and formalises the need for stakeholder education.

With the changing drivers (and even current ones such as the WFD) this is no longer

going to be acceptable. A more concerted and encompassing approach to the

engagement and education of all stakeholders is essential in order to build the

capacity to deal with the future challenges. There is a clear need for a cross-

institution stakeholder engagement and capacity building initiative; however, this is

may currently be difficult to achieve due to the inflexibility and intractability of the

existing regulatory and institutional arrangements that are restraining the

opportunities for innovative stormwater management in many European countries.

Currently the place of stormwater (and water) within formal planning processes in

many EU countries is not considered to be very important. In view of the future

uncertainties from climate change and impacts from current legislation (WFD in

particular), the place of stormwater management will need to take a more central role

in all aspects of urban planning. In addition, regulatory systems will need to become

more flexible and adaptable to new knowledge.

LIST OF REFERENCES

Commission Of The European Communities (2000). Directive 2000/60/EC of the European

Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community

action in the field of water policy, OJL 327 of 22.12.2000.

Commission Of The European Communities (2006). Proposal for a Directive Of The European

Parliament And Of The Council on the assessment and management of floods {SEC(2006)

66} (presented by the Commission). Brussels, 18.01.2006 COM(2006) 15 final

2006/0005(COD).

Commission Of The European Communities (2006a). Brussels, 17.7.2006 COM(2006) 397 final

2006/0129 (COD). Proposal for a Directive Of The European Parliament And Of The Council

on environmental quality standards in the field of water policy and amending Directive

2000/60/EC (presented by the Commission) {COM(2006) 398 final} {SEC(2006) 947}.

DTI (2006). Sustainable Drainage Systems – a mission to the USA. Report of a DTI global watch

mission. March 2006. UK Department of Trade and Industry.

Field, R., Pitt R., Heaney J. (Ed.) (2000). Innovative Urban Wet Weather flow management

systems. Technomic pub. ISBN 1-56676-914-0.

Field R., Tafuri A N., Muthikrishnan S., Acquisto B A., Selvakumar A. (2006). The use of best

management practices (BMPs) in urban watersheds. DEStech pub. Inc, Lancaster

Pennsylvania. ISBN 1-932078-46-0

Gammeltoft P. (2006). Evidence to Science and Technology Committee. 8th Report of Session

2005-6. Water Management.8th Report of Session 2005-6. Water Management. (Vol II) HL

Paper 191-II. Q627 p236.

House of Lords (2006) Science and Technology Committee. 8th Report of Session 2005-6. Water

Management. Vol. I: Report. HL Paper 191-I. Vol II: Evidence HL Paper 191-II. The

Stationery Office Ltd. London.

Juuti P S., Katko T S. (Eds.) (2005). Water, Time and European Cities - History matters for the

Futures. WaterTime project. EU Contract No: EVK4–2002–0095.

http://europa.eu.int/comm/research/rtdinf21/en/key/18.html.

Maestre, A., Pitt, R. E., Williamson D. (2004). ‘Nonparametric statistical tests comparing first flush

with composite samples from the NPDES Phase 1 municipal stormwater monitoring data.’

Stormwater and Urban Water Systems Modeling. In: Models and Applications to Urban

Water Systems, Vol. 12. (edited by W. James). CHI. Guelph, Ontario, pp. 317 - 338.

Middlesex University (Eds.) (2003). Review of the Use of stormwater BMPs in Europe. Project

under EU RTD 5th Framework Programme Contract No EVK1-CT-2002-00111. Adaptive

NOVATECH 2007 1703

SESSION 8.3

Decision Support System (ADSS) for the Integration of Stormwater Source Control into

Sustainable Urban Water Management Strategies. Unpublished report.

[http://daywater.enpc.fr/www.daywater.org/].

Mohajeri S., Knothe B., Lamothe D-N., Faby J-A. (2003). Aqualibrium : European water

management between regulation and competition. European Commission. ISBN 92-894-

6428-3.

Official Journal of the European Communities (2001). Decision No. 2455/2001/EC of the

European Parliament and of the Council. Establishing the list of priority substances in the

field of water policy and amending directive 2000/60/EC. 15.12.2001.

Roesner L., Pruden A., Kidner E M. (2006). Guidance for improving monitoring methods and

analysis for stormwater- borne solids. WERF draft report 04-SW-4.

Ross D., Thornton A., Weir K. (2004) Priority Hazardous substances trace organics and diffuse

pollution (Water Framework Directive): Treatment options and potential costs. UKWIR report

ref no. 04/WW/17/5. ISBN 1 84057 333 3.

UKTAG (2006) UK Technical Advisory Group on the Water Framework Directive. UK

ENVIRONMENTAL STANDARDS AND CONDITIONS (PHASE 1) Final report August 2006

(SR1 – 2006) UK Technical Advisory Group on the Water Framework Directive.

[www.wfduk.org].

1704 NOVATECH 2007

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- 5-Calcul D'un Réseau D'eaux Usées (Corrigé)Document4 pages5-Calcul D'un Réseau D'eaux Usées (Corrigé)Mamadou Niang71% (7)

- Carte Du Potentiel Radon Des Communes de La NièvreDocument1 pageCarte Du Potentiel Radon Des Communes de La NièvreAmélie JamesPas encore d'évaluation

- Examen Final B1.1Document5 pagesExamen Final B1.1Jose Andres Jaimes PicoPas encore d'évaluation

- Par ExxDocument96 pagesPar Exxva15la15Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cours HDR Sommaire 23 Mai 2015Document69 pagesCours HDR Sommaire 23 Mai 2015deziri mohamedPas encore d'évaluation

- Fiche EstimativeDocument2 pagesFiche EstimativeAbdelaly JabbadPas encore d'évaluation

- Math TescoDocument4 pagesMath TescoYoussouf DiakitéPas encore d'évaluation

- Chimie-TP3 Mesure Du PH de Solutions-CorrDocument2 pagesChimie-TP3 Mesure Du PH de Solutions-CorrChartier JulienPas encore d'évaluation

- Rapport SéparateurDocument7 pagesRapport Séparateursi parPas encore d'évaluation

- L'industrie de L'huile D'oliveDocument8 pagesL'industrie de L'huile D'oliveaminesa100% (1)

- Schematique HydrauliqueDocument1 pageSchematique HydrauliquehassenbbPas encore d'évaluation

- CP ADEME-DTT Charte Éco MobiliteDocument2 pagesCP ADEME-DTT Charte Éco MobiliteFred AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Boue Nord CamDocument4 pagesBoue Nord CamACIDPas encore d'évaluation

- Guide Branchements ONEPDocument35 pagesGuide Branchements ONEPSlimaneZarga100% (1)

- Expose Audrey Et Clara DiffuserDocument4 pagesExpose Audrey Et Clara Diffuser7000dyvezahxoPas encore d'évaluation

- Energie Evaluation Environnementale PDFDocument124 pagesEnergie Evaluation Environnementale PDFSissy carburePas encore d'évaluation

- Unité Sauvons La Planète PDFDocument12 pagesUnité Sauvons La Planète PDFSara RenovellPas encore d'évaluation

- 21 255 266Document12 pages21 255 266Mecif BrahimPas encore d'évaluation

- Session 9.biomass Exercise - FR (UNSD)Document5 pagesSession 9.biomass Exercise - FR (UNSD)Imane EmyPas encore d'évaluation

- M2P Hydrogeol TD1 2004 PDFDocument2 pagesM2P Hydrogeol TD1 2004 PDFKhaoula ZefanePas encore d'évaluation

- Etude D'impactDocument83 pagesEtude D'impactIbti100% (1)

- 1 Labo TP2Document12 pages1 Labo TP2Yahia BobPas encore d'évaluation

- 08 Hochbau Anwendung FRDocument57 pages08 Hochbau Anwendung FRNuno TomásPas encore d'évaluation