Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

1492 - The Debate On Colonialism, Euro Centrism, and History - J M Blaut

Transféré par

being_there0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

537 vues68 pagesTitre original

1492 - The Debate on Colonialism, Euro Centrism, And History - J M Blaut

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

537 vues68 pages1492 - The Debate On Colonialism, Euro Centrism, and History - J M Blaut

Transféré par

being_thereDroits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 68

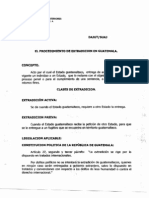

1492

Tag DEBATE ON COLONIALISM,

‘EUROCENTRISM, AND HISTORY

J. M. Blaut

with contributions by

‘Andre Gunder Frank

‘Samir Amin

Robert A. Dodgshon

Ronen Palan

Africa World Press, Inc. _

Contents

Foreword

Peter J. Tasior

Fourteen Ninety-two

LM. Blaut

Fourteen ninety-two Onee Again

Andre Gunder Frank

On Jim Blaut’s Fourteen Ninety-two!

smi Amin

‘The Role of Burope in the

Early Modera World Systom:

Parasitic or Generative?

Robert A. Dodgshan

‘The European Miracle of

Capital Accumulation

R-Palan

Response to Comments by Amin, Dedgshon,

Frank, and Palan.

LM. Blast

Index

st

85,

9

109

120

Foreword: A Debate on the

Significance of 1492

Peter J. Taylor

University of

weastle upon Tyne

Introduction

‘Some published debates work, others don't, This one

belongs firmly in the former category. The journal Poitea!

Geography has published a variety of publie debates in

recent years of which the one reproduced here is the Iat-

fest. The format used isa simple one. There isa main paper

by dim Blaut which strongly expresses a controversial the

ss, There are four commentators, two of whom are broad.

ly sympathetic tothe thesis (Gunder Frank and Samir

‘Amin) and two who disagree with i (Bob Dedgshon and

Ronen Palan. Finally Blau is given the opportunity to

comment on the commentators

"There are two main reasons why this debate aso uc

cess. Firat there isthe quality of the contributions

bbe prepared tobe persuaded by some quite contrary pos

tions! Second the question being debated sa very big one

‘with ervcial implications forhow we view the world ee ive

jn. It is for this reason that, as editor of Politica!

Geography, Tam delighted that thi partealar debate is

reachinga larger audience than the ofefonadas ofthe os.

nal. The main protagonist Jim Blast has asked me to con

tribute this short introduction tothe republication and T

decided to accept only could add some value tothe pro

‘uct. Obviously it would be inappropriate for me to jon in

the debate at this late stage, not to mention unfair to the

ther contributors, but I thought it would be useful for

readers iT attempted to place the debate into some sort

af context. Ihave already stated that I believe the debate

tobe an important one; itis now incumbent upon me to

say why,

All Historical Geography Is Myth

Al history Uhat is worth reading is contested history.

Any writer who thinks she or he has ‘settled’ some hi

‘orieal question is more interesting for what they repre:

sent than for what they say. To me the phrase contested

story initially rings to mind the battle of memoirs and

autobiographies that often occurs between great men’ ty

ing to ensure ther place for posterity. But there is much

‘more to historial debate than such purposive bias,

Wallerstain (1988) has asserted that ll history is myth,

[By thi he means that al historians bring to ther subject

rattor a set of assumptions about how the world works

Which determines the nature ofthe historia! knowledge

‘which they produce. Hence differen historians starting

from difforent positions each produce their different

‘myths’

Wallerstein uses the vory strong word ‘myth to empha

size hia distance from those who believe in th possibility

of producing an ‘absolute tru In history the later are

host represented by the Whig historians of the era of

British hegemony who thought that they could eventual

ly produce an ‘ultimate history’ when the Tast fact” was

finally interpreted (Carr, 1961) There are two key chal-

lenges to such thinking. The fist argues that all history

isa dialogue between the past and the present where the

contemporary concerns ofthe historians define the quas-

tions asked ofthe past (Carr, 1961). Itean be nother way:

‘woare trapped in the present, Hence we now intorprt the

Whig historical project with it emphasis on continuity

‘and progress culminating in Uhe present as acalobration,

‘and hence lgitimation, of the present. Now is made @

‘special time

"The second challenge argues that the postion an his

torian starts from needs to be speciied much moro pre

cisely than merely the present. Aa with other cultural

pursuit, historians have been in the business of what

Rana Kabbani (1988) calls ‘Zevise and rule. The present

is the modem and the modern is place, the West-Here

where the historian comes from — is made a ‘special

place: There is « geographical dialogue between places,

jost as inherently biassed asthe historin's one between,

times, in all descriptions of our world (Taylor, 1993). In

fact much geographical writing has boon more like a ge

_raphical monologue as the ‘moderns’ have scripted the

‘premoderae’ in Keeping them in their place. Hence we

can say thatall historical geography — understanding the

timer and places of ar world — ita myth, Thedebate con

Alucted her is above all about choosing between alterns:

tivehistorieal geography myths itis about trying to think

beyond the here and now.

‘The Greatest Ossian of Them All?

‘The controversial position tht Blaut proposes may be

deqeribed as characterising moat worl story as great

‘Orion: The Ossian was an epic poem that purported to

Shor that he fomering of adleval Calc eoltarcocorred

Inthe Highlands of Scotland and wot Island as common

1y supposed (Trevor Roper, 1989) Te was an eighteenth

century romantic nationalist forgery that was trying to

induces rewnting of Celtic historical geography periph.

tral region was being promoted to centre stage putting

{te more lustrous rival in Oe shade. In sinilar manner

Standard word histories can be characterized as making

aria was unl fairly recently a rather peripheral art of

‘loose ‘world-systom’, Burope, into a apecial place where

progress is to be found. This not to say the world histo-

ans have purposivaly frged the evidence asin the orig

{nal Ossian, but the results of their less purposive bias

hhave had the same effect except on 2 much grander sale.

In their slightly different wavs, Blast, Frank and Amin

‘make Ossian-iype accusations; Dodgshon and Palan

oubt, on somewhat different grounds, whether down-

srading the special or wnique nature of Burope aids our

Understanding of the modern world

Tam not going to deseribe the five positions argued

below any further than locating them inthe context just

provided. What Tean promi the renders is avery rich

Sebate and I would suggest that they would be hard put

to find the equivalent concentration of ideas in any other

publication of comparable length,

Who Has Got the Best Myth?

"This ia the question the reader is being invited to

answer. But answering isnot just a matter of assembling

the facts to decide. There i an important sense in which

facts should be respected and not manipulated unfairly

‘but that snot the prime issue hore. Ie is mich more basic

than that, Tt seems to me that neither side could put

together ast offucts that would satisfy the other side they

were proven wrong: ‘Tm sorry, you were right al long,

We are in tho realm of interpretation and that ie encum-

bered by thehistorographical aumptions described eat

Tier. But you, the reader, carry such assumptions around

in your head. Nobody reading this debate will come to it

‘san ‘intellectual blank you will have either celebrated

for mourned the events of 1492 this year and that will

indelibly mark your reading ofthe debate. Nevertheless

itis always a rofreshing exercise to read other people's

‘myth even though reading your side's rebuttale is more

reassuring.

But where docs allthis subjectivity leave ua? There may

‘veo abeate truth but we do not want to be pushed ita

tmestreme-tatt poston whereevery myth ita gd

tu overy other and we ust pick the one hat ula, There

re criteria for selecting between mtb Tuas odo with

‘that the slo purpose making her his coke.

Ttitisaseblary choice then we mill eed to take partic

tr aed tthe fa tame a at

tnppea for us fo collet our tories lead us tour fet.

Butourthore ar ltimately boat how oar weld works

nd that polite Hence the erieia wed in hisdcbale

tottlec a preferred myth wl be imately pols

ormy put thkistory ino about the pastor een

tne present but its prise reference ste fotre Tha was

Uhemensageaf the cla Whig hstoren ut aa much new

radical hifi Tele think eograpy i ot about fo

{ign places, or even our home place, butt prime space

‘eleenc th whole world. Tat was the menage athe

Sid imperialist geographies jst an much aa new radical

igographies.lonecstorical geography and itemytbs are

Stee ture ef the worl Tht the space me com

{extof the debate presented hee

References

(Garr, E,H, (1961), What Is History? London: Penguin.

Kablani, R, (1988), Burope’ Myth of Orient, London:

Pandora

"Tayler, P. J (199), Full circle, or new meaning for the

lobal? In The Challenge For Geography (RJ. Johnston,

Oxford: Blackwell

Trevor Roper, H. (198), The invention otradition: The

highland tradition in Scotland. In The Invention of

‘Tradition (E, Hobsbawm and T, Ranger, ods.) Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Wallerstein, 1. (1989). Historical Cepitaliem, Landon

verso

Fourteen Ninety-two

J.M. Blaut

sity of Minois

‘at Chicago

Introduction

Five hundred years have passed since Buropeans

arrived in America yt wo still dnt fully realize how sig

nificant that event sas for eltural evolution. 'am going

to argue inthis essay thatthe date 1492 represents the

brealepoint between to fundamentally different evol

tionary epochs, The conquest of America beyins, and

explain, the rise of Burope It explain why capitalism

rote to power in Europe, not elsewhere, and why capital

lmreets pver inthe heir, nt ater Foren

rinety-twe gave the world a center and a peshey.

Before 1492, cultural evolution inthe Eastern

Hemisphere was proceeding evenly across the landscape

in Afi, Asia, and Europe a multitude of enters were

volving out of (broadly) feudalism and toward ready)

spitaliam. Many of hese regions in all thre continents

‘were at the same level of development and were pro

ireasing at about the same rte nd (ast their modes of

Production inthe same direction, They were fat evel

Ineo axons in hemi wide never or

proces af evolving capitalists, Burope was notin any W

head of Aen and Asia in development or even in the

preconditions for development

‘Aer 1492, Europeans came ts dominate the world nd

hey dd oo brane 1492 inaugurated a et of world

tonealproestes which gave to European protocpitalats

aoa cal ad power odie eal in ther

own region and begin the destruction of competing proto

capitalist communities everywhere else By the endo Une

11th centry, ro hundred years ator 1492, capitalism or

capitalists) had risen to take polities and scil control

fa few Westera European countries, nd alia expan

sion had decisively begun in fea and Asin. Europe waa

"ow begining to dominate the world and toes the world

Inlevel and pace of development. The world's landscapes

wore now uneven. They have remained so ever sinc,

‘Nobody doubt tht the Gsawery and exploitation of

‘Ameria by Europeans had something to do with the iso

and modernization of Europe. What Lam arguing here is

‘much stronger and much more radical thesis, The argue

‘nents radial ina east ur respect

{ih Tedonies that Europeans had any advantage aver

‘Acana ond Asians prior to 1492 as regards te el

onary processes leading twerd capitalism ond

Imodersity. Modievl Burope was no more advanced or

progressive than medieval Africa end medieval Asis,

fand had na special potentialities —no unique gift of

‘atcnality or wenturesomencss!

Fain at the same time asserting that colonialism, as a

proves, lie a the heart (aat at tho periphery) of such

trord-historieal transformations as the rso of capital

{Sm and Europe, Capitaliem would (I suspect) have

frrived in any case, but it would have arvived many

Centuries later and it would not have seated itselin

Europe alone (or first) had it not been for European,

folontalien in Amerien. Later clonalism was eracial

forthe later evolution of capitalism (a thesis I eannat

pursue in this short essay) Colonisism, overall, has

Een a eruil dimension of espitaliem from 1492 down

to the present

T am arguing that the economic exploitation of

Americans in the 16th end 17th conturies was vastly

tnore intensive, snd produced vastly more capital, than

is generally recognized. The argument then moves to

rope, and claims — fllowing somewhat the lead of

tcarker writers like Ef. Hamilton (1929) and WP.

Webb (1981) — that economic, racial, and political

tMfects of ola! accorulation, principally in America,

produced a mojor transformation of European society

Pim parting eompany with thos traditional Marxists

‘who, like tracitonal conservatives, believe that the rise

Ut capitalism is to be explained by proceses internal to

Europe Strity speaking, there was no ‘transition from

Feudalism to capitalism’ in Burope;thore was rather @

tharp break, a historical unconformity, between

medieval Europe and the Burope of the bourgenis revo

Tution (or revolutions). That unconformity appears in

the historia column joat in 1492. After 1492 we see

tuddon, reveutionary change. There was no European,

{ronsiton instil another sense. A transition toward

topitalism and from s range of broad feudal and fe

Alal-teibutary modes of production was indeed taking

place before 1492, bat it was taking place on a hem

Ephere-wide scale, All of the Marxist models which

tempt to dtcover causality within an ftra-Europesa

system only — the decline af rural feudalism in Europe

(Brenner, 1976, 1977, 1982 the rie of Evropean towns

(Swecey, 1978) — are deficient because the real causal

ty is hemisphere-wvide in extent and effec,

Inthe following paragraphs I will present the reason-

ing behind these prepositions. The plan of procedure i as

follows. To begin with, Iwill ry to show that our magni

icont legacy of Burupean historical scholarship docs not

provide important evidence ayainst tho theory argued here

because itis nat really comparative. Iwill show thatthe

basic reason why we have accepted the idea of European

historical superiority is Burocentriedifusionism, thus a

‘matter of methodology, ideslogy, and implicit theory, not

empirical evidence. Nest, 1 will try to show that Europe

‘was at about the same level as Africa and Asia in 1492,

‘that a common proces of evolution toward capitalism was,

cocearving in a network of regions cross the hemisphere

This argument, stile preliminary to our main thesis (bt

fn essential step in laying out the overall theory), wil be

put forward in two brief discussions. First Twill very

sketchily summarize and ertcie the views of a number

of scholars who maintain that Europe was indeed more

advanced and progressive than ather regions in the Middle

Ages. Then I will sketch in the empirical basis for the

‘opposing theory, thatof evenness prior to 1492, here sua.

‘marizing prior reports (principally Blaut, 1976) We then

arrive at the main argument, which is @ presentation of

‘empirical evidence that colonialism after 1402 led to the

‘atsive accumulation of eapital (and. protocepitalist

power) in Europe, and t0 explains why Europe began its

Selective rise and experienced, in the 17th century, ite

political transformation, the bourgeois revolutions I the

Course of this discussion Iwill show that the discovery of

‘America and the beginnings of eolonialism did not reflect

fany superiority of Europe over Africa or Asia, bat rather

Pallected the fact of location,

Prior Questions

‘The Question of Evidence

Libraries are fll ofschlarly studies which seem to sup

port the historical propositions which [here reject, and

{eo of them in particular: the theory that Europe held

fsdvantages over Afriea and Asia in the period prior Lo

41492, andthe theory that the world outside of Buropehad

little to do with cutaral evolution after 1492, and thus

‘that colonialism was aminor and unimportant process, an

fffect nota cause, in world history from 1492 tothe pre

tent.

But existing historial scholarship does nat give much

support to these theories, although this is not generally

‘realized. Most of Uhe support comes fram unrecognized,

implicit beliefs which have not been tested empirically,

beliefs which are mainly an inheritance from prior times

‘when scholars simply did not question the superiority of

Europe and Buropeans Before we tura to our empirical

argument itis important to demonstrate why this iss

because no empirial argument presented in one short

‘essay ean otherwise soem ta have Une power to stand up

ta theories which are almost universally accepted and are

thought tobe supported with mountains of evidence gath-

tered by generations of scholars

"There is ofcource abundant historical evidenes for the

Middle Ages that European society was evolving and

changing in many ways, From the 10th century, the

thanges tended to be ofthe sort that we ean eonneet lori

tally with the genuine modernization which appeared

‘much ater: towns (in some periods and places) were grow

ing larger and more powerful, feudal society was change

{ngin distinet waye that oggest internal changer decay,

long-distance trade on land and sea was becoming more

intensive and extensive, and so on, All ofthis is clearly

shown in the scholarly record But what docs i-imply for

cultural evolution? And what doos tno imply?

It does imply that a process af evolution toward some

sort of new society, probably more or less capitalist in its

‘underlying mode of production, was underway in Europe

Tt doos not tell us whether this evolutionary process was

taking place only in Burope, Andt docs not provide ws with

the eritical evidence wich we must have to decide why

theevolutionary changes took place in Europe, for two res

sons: firstly, eitical changes in Europe may have been

caused hy historical events which took place outside of

Europe, so the fate of European history may not contain

the causes of evolutionary change; and secondly, for any

postulated cause ofan evolutionary change in Barope, if

the same process (or fact) ocurred outside of Europe bist

did not, there, produce the tame eet as it did in Europe,

wwe have good reason to doubt that this particular fact or

process wae causally efficacious within Europe (Lam using

Seommon-iense notion oft the nation which we use

Pragmatically whenever we speak about causes and effects

fn human affairs, whatever some philsophers may say in

bjection )

‘Ofcourse, none ofthis precludes the spinning of grand

Ihstorical theories as to what caused evolutionary change

in European society at any given period in history, before

1492 or after. My point is that such theories cannot be

‘proven; they donot rst inthe faccual evidence bt rather

Ina prior beliefs sbout the causes of historical change.

‘The mountain of fctual evidence does not realy help ws

tedecide whether causes are ezonomie or political, or ntel-

leetual or technological, or whatever. Wercan weave these

facta into almost any sore of explanatory model, But we

cannot prove our cae. In sum, our great heritage of esre-

fal, scholarly stadies about European history does nat, by

Itself, provide evidence against any theory which clams

that the causal forces which were at work in Europe were

also at work elsewhere

Diffusionism and Tunnel History

‘There one primordial reason why we donot doubt that

Buropeans have taken the lead in history in all epochs

before and after 1492, andithas litle to do with evidence

It is a basic belief which we inherit from prior ages of

thought and searely realize Uhat we hold: its an impic

ithelie, not an explicit one, and itis olargea theory that

{tis woven into all of our ideas about history, both with

in Burope and without, This the theory, of uper- theo

ry, called Burocentre difasionism (Blaut, 1977, 1987s),

Diffustoniem is a complex dotrine, witha complex his-

tory, but the essence is clea. It became codified around

the middle ofthe 19th century ae part of the ideology of

evolving capitalism in Europe, but more specifically

because it gave powerful intellectual support to ealonal

iam, Its basic propositions are the following:

G) ieds natural and normal to find cultural evoktion pro-

fretsing within Europe

(2) The prime reason for cultural evolution within Europe

fs some fee or factor whichis ultimataly intellectual

br pirtaal, a source of inventiveness (dhe inventions

being social aswell ss tachnologiel, rationality, inno

tiveness, and virtue

(@) Outside of Barope, cultural progress is not to be expect:

‘ed: the norm is stagnetion, ‘traditionalism and the

like,

(4) Progress outside of Europe reflects diffusion from

Europe of traits (in the aggregate ‘civilization invent-

ed in Burope.

(6) The naturel form of interaction between Europe and

rnon-Burope is transaction: the dfusion of sanovative

‘eas, valoes, and people from Europe to non-Europe

the eounterdiffsion of material weelth, as just eon

pensation, from non-Europe to Europe. Thre is also

fifereat kind of counter di fusion, from periphery to

tore, which consist of Uhings backward, atavisic, and

‘onclzed: Back magte, plagues, barbarians, Dracula,

ton this being a natural consoquence af the fact that

the periphery Is ancient, backward, and savage.)

‘Thus in estonce: Europe invents, others imitate; Europe

‘advances, thers follow (or they ae ed.

Certainly the primary argument of difasionism isthe

superiority of Europeans over non-Buropeans, and the con

‘ception that history outside of Burope is made by the dif:

fusion from Hurope of Buropeans and their intellectual

fand moral inventions. But the iaternal, or ove, part of

the model is rtial when wetry to analyze the ways (eel)

Europeans theorize about their own history and their own

sacety, past and present. This part of difasionism om:

bines we doctrines derived fom dfusionist propositions

ro, Land no, 2) which involve a kind of historical tunnel

Yision, and so ean be called tunel history (Blau, 1987,

chap. 7, and forthooming). The first doctrine declaros it

‘unnecessary to look outside of Europe fr the causes of his-

{orieal changes in Europe (except of course deevvlizing

changes ike barbarian invasions, pages, heresies, et).

Historical reasoning thus looks back or down the tunnel

oftime for the enuses of al important changes: ontside the

tunnel isthe rockbound, changoles, traditional periph-

ery, the non-European world. This becomes 2 definite

‘methodology in European medieval history. Prior gener

ations of historians did not seriously look outside of

Europe, except to. make invidious comparisons, If

European historians today on some occasions try to be

comparative, cross-cultural, in their efforts to explain

Europe's medieval progress, the efforts almost invariably

make use of older, colonialera Buropean analyses of nen:

European history, and (unsurprisingly) reproduce the

older diffustonist eas sbout such things as'Asiate stag

nation, ‘African savagery’ and the lke, Crotura to this

point below) So tunnel history persist. Tt persists even

ormodern history: progress in the modern world is accom

plished hy Europeans, wherever they may novt be setled,

land by the entorprises putin place by Europeans.

"The second doctrine is more subtle. Just as difasionism

claims that itis the intellectsel and spiritual qualities of

the Buropean which, difusing outward over the world,

boring progress, 20 t claims that these qualities were Uhe

‘mainsprings of social evolution within Europe tele. Some

‘ualifcatons, however, are needed. Two centuries ago it

was axiomatic that God and His church were the foun:

{ainhead of progress. A Christian god of course will pot

{od ideas inthe heads of Christiane, particularly those

Christians who worship Him in the right way, and He wil

Tead His people forward to civilization. Gradually this

explicit doctrine became implicit, and Christian

pans were themselves seen asthe souress af innov-

aliveideas and hence evolutionary change, for reasons not

Cosually grounded in foith, Not until Marx did we have a

theory of cultural evolution which defintely placed the

prime cause ofehange outside the heads of Buropeans, but

{he habit of explaining evolutionary change by reference

taanautonomows realm of xdeas or ideology of supposedly

rational and moral innovation, remains dominant even

{day because ideologica-level causation is stil, ast was

when Mare and Engels criticized it in The German

[Hdeotogy, the best rationalization for elitist socal theory

(arxand Engels, 1876). Inany event, today the favoured

theories explaining the so-called ‘European miracle’ are

theories sbout Europeans ‘rationality, innovativeness’,

fand the rest. This holds true even for theories which

{round themselves in supposedly non-ideologiea! Tact,

notably technological determinism and social-structural

determinism. Technology may have caused socal change

in Medieval Europe but it was the inventiveness of the

Europeans that caused the technology, Likewise social

structures, which also had tobe invented

‘The Question of Alternative Theories

Complementing difusionism is a second external or

non-evidentiary source of persuasiveness for the theories

‘which discover European superiority inthe Middle Ages

‘and later, This inthe absence frm historians’ usual de

‘ouree of any competing theory. As we well know from our

Aoctrines about the methodology of social scionce, itis very

4ifcut to eriicze, or even gain a perspective on, one the

‘ory unless you have in mind anather, alternative theory

(theory cannot simply be ‘confronted with the facts)

‘Thereis no shortage of such alternative theories about the

rise of Burope and capitalism, before and after 1492. One

{the theory offered here: thateapitaism and modernity

‘were evolving in parts of Europe, Africa, and Asia in the

same general way and atthe same rate up tothe moment

‘when the conquest of America gave Burope its fist advan

tage, and thet the rse of Europe, and of capitalism with

in Burope, therealer was the vectorial reeultant ofthese

initial conditions, the iflowingof power from colonialism,

and derivative intra European effects

‘Bat there are numerous ther theories denying the idea

of the ‘Buropean miracle, For instance, iis argued by

‘some Marxists that, in the 17th eontury, Buropeans had

4 vory minor advantage in terms of procestes tending

toward the rise of capitalism, an advantage which other

societieshad held in prior times— think ofa fot-ace with

frat one, then another runner taking the lead — but rom

the moment the bourgesisie gained definitive contral in

northwestern Europe, o oer bourgensie anywhere ele,

‘nuld gain such contro, given th explosively rapid growth

‘and the power ofapitalism, even nits preindtral form.

Tn second theory, Europe managed ta break out of the

hemisphere-vide pettorn of feudalism because of ite

peripheral position and rather backward character, which

‘gave its feudal socity (and elass relations) a peculiar

Instability and hence led toa more rapid dissolution of few

alism and rise of eapitalism. (See Amin, 1976, 1985.) In

‘third theory, Buropeans had one special cultaral char:

‘acteristic indicating, nt modernity or eivilizatio or pro

iressiveness, but savagery: a propensity, not shared by

‘ther Bastorn Hemisphere societies, to attack, conquer,

enslave, and rob other people, Uhos to rss’ by predation

(This view is held by a number of very anti-European

‘scholars, You will notice that its the ‘European miracle?

theory inverted.) Still other theories could be listed. So

‘there are alternatives tothe theory of Burope’s primacy.

‘And the known facts fit these alternatives jst as well or

badly) they do the theeries of European superiority

Before Fourteen Ninety-Two

‘The European Miracle

The first claim which Tmake in this essay is that Burope

dna no advantage over other regions prior to 1492, Thave

argued this eponfc case elsewhere, and the argument wil

be briefly summarized below. However, the opposing the-

‘ony isso widely argued that itis best ta begin with a bret

sketch of some ofthe better-known modern theories which

fssert that medieval Europe ws already in terms of ul

tural evolution, the leader among world cultures. My pur

pose in presenting thee mink-ertiques especially and

‘only to show that this paint af view isnot selFevidently

‘convincing: nothing more can be attempted, given the im:

tations of a short essa.

think i unlikely that any Buropean writer of tho 18th

century doubted the historical superiority of Europe.

Perhaps Marx and Engels came closest to doing $0

Rejecting ideological eve theories ofhistarcal causation,

they speculated that Europe was the fest civilization to

faojuire class modes of production boease of its natural

fenvironment, Asia was dy; therefore Asian farming peo

ples had to rely on irrigation; therefore it became neces

‘ary for them to accept an overarching command structure

‘which would alloste water and maintain waterworks, 2

Special ort of power stracbure which was not truly a class

state, The farming villages remained classless. The plit-

{cal authority was not a genuine ruling (and aecurmolat

ing) lass, So there was no class strogule — the Marxian

motor of progress — and sceordingly no evolution into

Slave, feudal and capitalist modes of production. Soe

Marx, 1975; Engels, 1979, Engels probably abandoned this

view and the atsociated idea of an ‘Asiatic Mode of

Prodition’, i the 1880s. See Engels, 1970.) In tropical

regions nature was tao lavish to encourage socal devel

‘pment (Mars, 1976: 512), Barope won, #0 to speak, by

‘default. What is most important shout this incorrect f=

‘mulation is the face that it does not posit an ancient and

‘ongoing superiority of Buropean culture or the Buropean

‘mind.

‘Mest ofthe later Marxists and Neo-Marsists, perhaps

because they were unwilling to credit Buropeans with cal-

‘ral or ideological or environmental or racial superiority

yet had no strong alternative theory, tended to avoid the

problem of explaining Europe's apparent historical prior

fy (See, eg, the essays in Hilton, 1976) Notable excop-

tions in this regard are Amin (1976, 1985), whote views

‘we noted previously, and Abu-Lughod (1987-88, 1989),

‘who argues that many parts of Europe, Asia, and Afi

‘were at comparable ave of development the 13th een:

tury

otable in a different sense are the views of Perry

Anderson and Robert Brenner, whose theories are wide:

Iyapproved by non-Maraist social thinkers beeause they

seem to argue to the conclusion that Marat theory is

rot really diferent from Non-Marxist theory in its

‘pproach tothe question of the rise of Burope and ofeap-

italian, and no less friendly to Eurocentric diffusions

(See Anderson, 19748, 1974b; Brenner, 1976, 1977, 1982,

1986.) Anderson's formulation is quite close to that of

Weber (infra) in its argument that Ruropeans of classi

cal and feudal times wore uniquely rational and analy

fea, and that the feudal superstructure (not the economy

trelase struggle) wos the primary force guiding medieval

Europe's unique dovelopment. Brenner's theory, which

is highly iaduential (seo, eg, Corbridge, 1986; Hall

1985; Bacchler et al., 1988), is not at all complicated

Cass struggle between serfs and lords, influenced by

depopulation, led to the decline of feudalism in north:

western Europe, Brenner does not mention non-Europe

‘and scarcely mentions southern Europe.) In most parts

‘of northwestern Europe, the peasants won this lass

Struggle and became in essence petty landowners, now

fatified with their bucolie existence and unwilling to

Tnnovate, Only in England did the lords maintain their

vip on the land; peasants thus remained tenants. The

peasantry then became differentiated, producing a class

‘of landless labourers anda rising clas of larger tenant

farmers, wealthy enough torent substantial holdings and

forced (oeause they had to pay rent) to commercialize,

innovate technologically, and thus become capitalists.

(Brenner thinks that serfs, lords, and landowning peas:

ants did not innovate, and that towns, even English

towns, had only a minor role in the vise of capitalism.)

English yeoman-tenant-farmers, therefore, were the

founders of capitalism. Stated differently: capitalism

trose because English peasants lat the lass struggle

In reality, peasants were not predominantly landovn-

fers in the other countries ofthe region capitalism grew

‘more rapidly in and near the towns then in the rural

‘countryside; and the technological innovativeness which

[Brenner attributes to 14th-l6th century English farm

cers really occurred much later toe late to fit nto his the-

fry. More importantly, commercial farming and indeed

‘urban protocapitalism were developing during this per

‘odin southern Europe and (a T wil argu) in other on

tinente. Brenner's theory is simply wrong. Its popslarity

is due principally to two things. First, put forward as a

Marxist view, grounded in class struggle, it proves tobe,

‘on inspection, « theory that is feirly standard, if some.

‘what rural in bias, It seems to follows that class-strug

ile theories Tead to conventional conclusions. And

econdly, Brenner uses his theory (1977-77-92) o attack

the unpopular ‘Third-Worldist” perspectives of depen:

dency theory, underdevelopment theory, and in partiew

lar Sweeay, Prank, and Wallerstein, who argue that

European colonialism had much todo with the later rise

of capitalism. (See Frank, 1967; Wallerstein, 1974.)

Brenner is a thoroughgoing Buracentric tunnel histori-

fan: non-Europe had.no important role in social evolu

tion at any historieal peri. Unaware that colonialism

Involves capitalist relations of production — see below

he claims thatthe extrs-European world merely had com

rmereal effects on Burope, whereas tho rise of capital

{sm was in no way a product of commerce: it took place

{n the countryside of Bngland and reflected class strug-

ale, not trade. (See critiques of Brenner by R. Hilton, P.

Groot and D. Parker, H. Wander, E. Lefty Ladurie, G

Bois, JP. Cooper, and others collected in Aston and

Philpin, 1986, S00 Torras, 1980; Hoyle, 1990.)

Certainly the most influential theory in our contary is

that of Max Weber, Weber's theory is built up in layers.

‘The primary layers conception of Europeans as having

been uniquely rational’ throughout history. Whether or

sot this attribute of superior rationality rests in turn, on

‘Amore base layer of racial superiority is not made clear

{On racial inBuences, ee Weber, 1951: 230-32, 379; 1958:

‘3031; 1967: 387; 1981: 379). Such a view was indeed dom:

inant in mainstream Buropesn thought in Weber’ time.

‘Weber, however, considered non-European Caucasians 8

well at non-Caueasians to have inferior rationality. But

Ihe didnot offer a clear explanation for the superior ratio

nality of Europeans, nor even a clear definition of

‘ality(See Leith, 1982-41-62; Freund, 1969. See Weber,

O51. 1-82 for an exhaustive lst of the ways in which

Buropeans are uniquely rational.) European rationality,

in urn, underlay and explained the unigue dynamism of

great range of European social institutions laut forth-

Coming). The role of religion was considered crucial,

although it appears that Weber considered different reli

tions tobe either more o less rational, hence gave causal

primacy to rationality. Other traits and institutions are

then viewed mainly as products of rational thought (era:

cially including valuation), sometimes in direct causality,

Sometimes via religion (as when Confucianism i blamed

for some negative traits ofthe Chinese and Christianity

is crodited for some positive traits of Europeans: see

Weber, 1961: 226-49), although Weber waa neither sim-

plistic or deterministic, and gave carefl attention eo

homie and even geographic factors as well as. the

‘eologiallevel ones, The moat important outcomes of

superior European rationality, sometimes expressed

through religion, and modified in ways Thave mentioned,

fare these: urbanization processes in Europe which favour

‘economic development in contrast to those of non-Europe

which are not dynamic, however grand they may be in

teale; landholding systems in Europe which point toward

private property and toward capitalism in contrast onon:

EBraropean land systems in which the holders only atom-

porary occupant, granted land on condition of service; and

overnmental systems, such as bureaucracy, in Burope,

‘which are efficient, rational, and progresive,ualike non.

Buropean systems which are rigd and stagnant, Weber

is probably the most important and briliznt modern ana

|yst of socal phenomena in general and European society

in particular, bot his theories about European superior

ty over other civilizations are unfounded. The ‘rational

ty which is claimed to underlie ather facts is purely a

theoretical construct, which Weber defends ancedotaly

Example: ‘The typical distrust of Uhe Chinese for one

‘another is confirmed by all observers I stands in sharp

fontrast othe trast and honesty of the [Purtansy: Weber,

1951: 282.) Europeans, throughout history, have not dis

played more intelligence, virtue, and innovativeness than

‘on-Buropeans. If pre-1492 urbanization is fairly com:

pared, epoch for epoch, Europe does not stand out! the

Weberian image of medieval Buropean cities as uniquely

fro, uniquely progressive, ote. is invalid See Brenner,

1976, Blaut, 1976; GS. Hamilton, 1985.) Feudal land:

holding eystemns included both service and property like

‘tenure both in Europe and in non-Burope. The rational

politcal nstittions of Burope are results, not causes, of

‘odernization. And so forth. In sum: Weber's views of non

Europe were mainly a codification of typical turn-o-the

century difasionist prejudices, myths, and half-truths

bout non-Europeans. They prove no European superior

Sty for pre-modern epochs

’As geographers we are (for ou sins) familiar with anoth

cer kind of argument sbout the superiority of Europeans,

fan argument grounded in what seem to be the hard facts

ofenvironment, technology, demography, and the like, in

ooming contrast to ideologicallovel theories ike those of

(typical) Weber. In Rittrs time, the Buropean environ

ent was considered superior because God made it 0.

‘Some historians ofmore recent times, however, invoke the

environment as an independent material cause.

[Northwestern Burope has a climate favouring ‘human

‘energy’ and agriculture (Jones, 198: 7,47). (This is ol

fashioned environmentalism) Is oils are uniquely fertile

(Mann, 1986; Hall, 1985). (Mfore environmentalism.) Its

indented coastline, capes and bays, favour commerce.

(Archipelago, rivers, canals, and snindented coats are

{inno way inferior, nor wasland transport 1000 years ago)

Recent historians also repreduce the ld myth about Asian

aridity, deducing therefrom irrigation-based societies,

thus Oriental despotism (nowadays described asa propen.

sity toward the “imperial state) and eultaral stagnation

(Witfogel, 1957; Jones, 1981; Hall, 1985; Mann, 1988).

But most farming regions of Asia are not at all arid, And

Teappears that most of the recent arguments positing

and explaining the ‘Baropean miracle’ have a definite, if

fot always clesrly stated, logical structure. European

superiority of mind, rationality, the major independent

and primary cause. Europe's superior environment is the

‘minor independent cause, invoked hy many (perhaps mest)

historians but not given vory much weight. Bach histor

fan then points to one or several or (usually) many

European cultural qualitios, atone or or more historical

periods, which are explained, explicitly or implicitly, as

products of European rationality or environment, and then

fre asserted tobe the elective causes, the motors, which,

propelled Europe into a more rapid social evalition than,

hhon-Europe. There are many ‘miracle theories, difering

{nthe parts ofelture chosen at eatte and the time-per

‘odand place) chosen aa venue. Sometimes the same argu

mentstructure is used with negative assertions about

‘non-European cultural qualities. The popular word now is

“blockages. No longer claiming that non-European soc

‘ties are absolutely stagnant, and absolutoly lacking in

the potential to develop, historians now assert that such-

fand-euch a cultural feature blocked developmentin sch

fand-such a society. (Peshaps just an improvement in

hrasing.) By way’ of conehoding this brief discussion of

‘miracle’ theories, Iwill give afew examples of formal:

tions which have this strucare of argument.

‘Tynn White, Jr. (1962) has pat forward the strongest

‘modern argument that Buropean technology explains

Burope’s unique medieval progres. On close inspection,

the argument is not about technology but about rational

‘tg: Buropeans are uniguely inventive (White, 1968)

Rather magically a numberof crucial technological inno

vations are supposed to have popped up in early medieval

borthern Europe, and then to have propelied that region

into rapid modernization, Three of the most crucial traits

fre the heavy plough, the threefield system, and the

horsecollar. The heavy plough is assigned, by White, a

tentative central-Buropean origin in the Oth century, then

iffased quickly throughout northwestern Burope, and

‘doce much to account for the burating vitality of the

Carolingian realm’ (White, 1962:54) Adoption ofthe trait

Jed to a socal revolution in northern Burope. It forced

peasants to Tearn cooperative endeavor. It was crucial to

{he rise of manorialism (p. 44). It produced a profound

‘change in the ‘attitude tomard nature’ and towerd prop

‘erty (p.58). In fact, the heavy plough definitely was ert

‘alin opening up large regions of heavy, wet sol, thus in

‘enlarging ealtivated acreage. But Une heavy plough, with

‘teams of upta24 oxen, wasn use in northern India before

the time of Christ (Kosambi, 1969; Panilekar, 1959). In

Europe it reflected either diffesion o relatively minor

adaptation oflighterplough-technology, long used in drier

parts of Europe, Moreover, all of the causal arguments

from plough to social change can be reversod: the evalu-

tion of fendalism led to an immense demand for more eul-

tivated acreage, and this led to an adaptation of plough

technology such that hesvy-til regions could now be cul

tivated, The technology i effet, not eause, and Europeans

‘re not displayed as uniquely inventive and thus unique

ly progressive. White's arguments concerning the three

field system and the horse-collar deserve roughly the same

responce Blaut forthooming), as do al ofthe other tech

‘ological traits discussed by White (1962), most of which

‘ther difsed into Europe from elaowhere or were evolved

{ncommon among many cultures in many regions. White's

explanation for the supposed sniquely inventive charac

{er of Buropeans is quite Weberian. Buropean inventive-

ness is attributed basically to ‘the Judeo-Christian

{eloology’ and to Western Christianity. The former under

Ties the Exropean’s unique faith in perpetual progres

(White, 1968! 85), which becomes a fith in technology

‘The latter produces'an Occidental, voluntarist realization

‘of the Christian dogma of man's transcendence of, and

Fighifel mastery over, nature..(Thore is no) spirit in

‘ature’ (p. 90), Nature is tol. But medieval Europeans

tended nat to belive in progress: Gd's world was ereat

fd perfect and entire. This belie is not anciont but mod:

tern; White is simply telescoping history. And medieval

Buropeans did not separate man from nature: they

believedin the plenum, the great chain ofbeing, the pros-

‘ence of God in all things. Moreover, Eastern Christianity

fand non-Christian doctrines have parallels with the

‘Western ones, This is not an explanation

Inthe 1980s a namber of works appeared which strong

ly defended the historical superiority of Burope and the

‘Basie diffusioist thesis that non-Europe always lagged

in history. The most widely-discassed of these works it

Erie Jones’ book The European Miracle (Jones, 1981).

‘Jones, an economic historian, assembles essentially al of

the traditional arguments for Barope’s historical supers

ority, including some (ike Europes ‘climatic energy’)

‘which have been definitively refuted, and adds to those a

‘umber of coloialera mths about the cultaral and pay=

Chologieal inability of noa-Buropean societies to modern.

102 19

{e. Jones basic arguments are the following:

(G1) Burope'senviruament is superar to As

(2) Buropeans are rational, others are nt

(8) Ava result oftheir superior rationally, Europeans con

trol thoie population, and so accumulate wealth and

resources, whereas others donot.

‘The argument is doveloped in a series of steps. Firs,

Jones invokes environmentaliem to make various spar

tu claims about the superiority of the European envi

ronment, about Asa'sargity and Une consequent Oriental

‘espotiam, “authoritarianism, ‘pliial infantilism (p10)

fete. Neat, hestatesas fact the emplotaly speculative claim

that ancient northern European society had qualities

favouring progress and population control and so set

‘Buropeans on their permanent course af development. The

claim is that lack of irrigated agriculture (the root of

(Oriental despotism) and rustic forest life led to individu

lism, love of freedom, and aggressiveness thus @ unique

psychology, and als to the favouring ofthe naclear fam

fly, Only speculation leads one from known evidence about

settlement patterns to the conelusion that early Buropeans

hed a special partiality toward nuclear families, Jones

confuses ettlement, household, and kinship.) Jones sim

ply asserts that the north-European post Neolithic nuclear

family became a permanent (and unique) European trait

snd permitted Buropeans — in contrast to Asians — to

‘void the Malthusian curse of overpopulation. (ere he

repeats the myth of early modernization theory that

‘nuclear families somehow lead toa‘preference for goods

rather than for children’ p. 12.) There is no reason to

believe that anciont European cultures had any qualities

Ltniquely favouring historisl change: this is merely one

ofthe classi Buropean prejudices

‘Jones then proceeds to explain the rise of capitalism,

‘Thisrefleted environmental factors, ancient cultural fac-

tors, and also particular medieval outcomes. Jones repeats

White's arguments shout technologieal inventiveness

Europe was a uniquely Snventive society (p. 227 ). Be

nd Africas

cera, He constructs a theory tothe effet that Europe's

‘environmental diversity produced a pattcrn of separate

mall states, the embryos of the modern nation-states,

Whereas Asia's supposedly uniform landscapes favoured

(long with irrigation) the imperial form of government.

‘Tones (also see Hall, 1985) claims that empires stifle oxo

‘omic development, although he gives no reason other

than the saw about Oriental despotism and the false pie-

ture of Asian landscapes (which are as diversified asthe

European). Hisbasicargumont-form is: capitalism and no

empire in Europe, no capitalism and empire in Asia, ergo

fempire blocks capitalism,

‘Tne final stop i to thow that Asia and Africa had no

potential whatever for development. Jones calls this ‘the

comparative method (p. 158) but iti really just a string

ofegative statements about Africa and Asia. Afia is dis

posed of witha few naly comments. Tn Afi, man adapt

fed himself to nature. felt part ofthe ecosystem..not above

ftand superior (p. 158) Africans did not know the wheel,

made no contribution to world civilization. Etcetera

‘Asians do not have the capacity fr logical thought (pp.

161-3). They have a ‘servile spirit, a Tove of luxury’ (p.

167, There is much thievery, senscless warfare, obscu:

‘antiom, and general irrationality, particulary in matters

‘of sexual behaviour. ({in Asia] population was permitted

to grow without. deliberate retraint..Seemingly, copa:

lation was preferred above commodities p15.) Jones co:

cludes that such societies could not progress in history

Development ‘would have been supermiraculeus(p. 238).

Tack the space to review other recent efforts ofthis aor

toprovethat there wasa'European miraclé and toexplain

it. Brief mention should however be made of eerain argu-

‘ments put forward by John A. Hall (1985, 1988) and

‘Michael Mana (1986, 1988). (See Blaut 1989, Both Hall

‘and Mann adopt the major arguments of Weber, White,

‘and Jones, including the aridity-irrigation-despotim for.

‘mala, then add speci arguments of their own. Mana

thinks that ancient Buropeans acquired a pecliarly demo:

cratic, individualistic, progressive culture, with power dis:

persed widely instead of being concentrated despoticaly,

because, among other things, they adopted (and presum-

ably invented) iron-working in agriculture, iron being

‘widely available to the individual peazant (but we do not

know where iron metallurgy was invented and iron-work

{ng was adopted rather quickly from Chinato West Afeiea).

He also posits a teleological tendency of Europeans to

‘march northwestward, cloaring marvelously fertile land

as they proceed, eventually reaching the sea and, with

peculiar venturesomeness, expanding across the world.

Tike Weber and White, he gives a major rolein this march

to Western Christianity, claiming that it gave West

Buropoans historical advantages over pooples with other

religions Hall prefers to emphasize Europeans’ uniquely

progressive polities along with Europeans’ uniquely ratio

zal demographiebehaviour the relative continence ofthe

European family Hal, 1985: 131), In Indi, caste hebbled

state development, India didnot have plitial history

76. India had no sense of brotherhood Hall, 1988: 28.)

Jn China, empire prevented progress. The Islamic realm

‘was mainly a zone of tribal nomads with e fanatical ide-

‘logy and only unstable polities. Europe had an impli.

ly modern organic) state from very early. None ofthis

equlres comment

‘The new uropean miracle literature exemplified by

‘the works of Jones, Mann, and Hall should be seen in per

spective. Tn recent deeades a reaction to Burocentric his:

tory has emerged, a kind of Third-Worldist revisionicm,

with notable contributions by J, Abu-Laghod, H. Ala, 8

Amin, M. Bernal, A Cabral, J. Cockeroft,B. Davidson,

AG. Frank, C. Furtado, B, Galeano, I. Habib, CLLR.

‘James, M. Moreno Fraginals, J. Needham, W. Rodney, 2.

‘Suid, RS, Sharma, R. Thapar, 1, Wallerstein, B, Williams,

and many other European and non-European writers.

tense that Eurocentric historians basiealy ignored this

revisioniem for some time, then, i the 19708, ean avig-

brous counterattack. Although the revisionists had not yet

focused on pre-1492 European history, it was evident that

the counterattack would have t strengthen the founda

tion axiom that Burope has been the evolutionary leader

among world civilizations since far back in history, long

before 1482, proving that non-Europe has not contributed

Signifieantly to European or world history, and that non:

‘Burope's underdevelopment resulted from its owa histor.

{eal failings (stagnation, blocked development), not from

Buropean colonialism. This isthe new wave of diffusion

ist tunnel history

Landscapes of Even Development

‘Was Europe more advanced in level or rate of develop

ment than Asia snd Africa in the late Middle Ages? The

evidence which I will now summarize suggests that this

Was not the ease. (See Blast, 1976, 1987b, 1989a,) The

major modes of produetion which were widespread in

Europe were also widespread in the other continents, The

calearal attributes which would tend tbe involved in ul

tural evolution out of feudalism and toward capitalism ad

‘modernity were present in the main social formations of

‘Asia and Africa aswell as Burope in 1482. Ido not think

itis necessary to insist upon a definite theory, Marxist or

‘on-Marxst, asta how and why feudalism decayed and

tapitalism (and modernity) arose, in order to defend the

thosis that the process, viewed at the continental scale,

was going on evenly, not unewenly, across the medieval Old

‘World, The part of clture which seem to me ta be cen:

tral tothe process, namely, forms and relations of pro

Auction, urbanization, large-scale commerce and

‘commodity movement, and he ideas and socal structures

‘associated with economic and technological development,

allseem tohave been present in many societies across the

hhemisphere. Moreover, there seems to have been a single

{nteroommunieating socal network, in which criss-cross

diffusion eproed each new development widely across the

hemisphere, leading to even, intbond of uneven develop

sent. {have argued this thesis elsewhere, and will very

briefly summarise it here.

Perhaps half of the agriculturally settled portions of

Africa, Asia and Burope had landlord dominated societies

in which surplus was extracted from peasants, some of

‘whom (in all three continents) wore serfs, others fre ten:

fans, The mode of production was feudal eee Blat, 1976).

The European version of this mode of production had no

special characteristics which would suggest more rapid

‘transformation into another modo of production. To give

fs few examples: the European manorial system, some

times considered a milestone on the road to private prop.

erty and production, had parallels in China and India and

‘doubtless elsewhere (including sub-Seharan Afeiea), and

fm any ease the integrated demesne had largely disap-

peared in Western Europe. by the. 13th century

(Choudhary, 1974; Elvin, 1973; Fei, 1958; Gopal, 1963:

Isichei, 1985; Kea, 1882; Liceri, 1974; Mahalingam, 1951,

‘Sharma, 1965; A, Smith, 1971; Watson, 1983; Tung, 1965;

‘Yadava, 1974), Serfdom tended to decline in Europe from

the 14th century, but medieval-peried tenancy based on

‘untied peasants was idespreadin South China and other

places, and was sometimes (asin Fukien) associated with

fommercial production of industrial producte (Rawski,

1972). The European feudal estate was nt closer to gen:

tune cumlable private property (and eapital) than were

‘states in many other areas, including China and part of

India, (The old generalization, popularized by Weber, that

‘Asian land ownership was based on service tenure while

‘the European was heritable private property is simply hi

torially untrue, Service estate tended evelve with time

into privately owned estates, service tenure was legally

characteristic of feudal Europe as much as most other

regions, and rotation of estates tended to reflect special

Situations of politico-military instability. See Chandra,

1981; Chicherov, 1976; Elvin, 1973; Gopal, 1983;

‘Mahalingam, 1951; Sharma, 1995; Thapar, 1982.) The

cash tenancy which replaced serfdom in some parts of

‘Western Biarope in the 14th and 15th century had close

parallels in other continents (Alavi, 1982; Chandra, 1981;

Kea, 1982; Rawski, 1972; Yadava, 1966) And soon

‘Was feudalism collapsing in Burope more rapidly than

clsowhere? Two common measures used to judge this

Point are pessant unrest and urbanization (implicitly

Fural-arbam migration). Peasant revolls seem to have

‘been widespread and intense in other continents

(Parsons, 1970; Harrison, 1968). The movement to towne

was fanything les intense in Europe in the Iter Middle

‘Ages than elsewhere, since urban population sil repre-

‘ented a mich lower percent of total popations than in

many non-Burepean regions (perhape including sub-

Saharan Africa: soe Niane 1984), lower even in classical

feudal countries like France than in the Mediterranean

countries of Europe. Doubtles, feudalism was eollaps-

{ng or erambling, but chis was happening at relatively

slow rate and was happening als elsewhere inthe hem

Sphere (Alavi, 1982: Chandra, 1981; Chicherov, 1976;

Elvin, 1978; Kea, 1982),

1 suspect that Marx and Engels were rightin seing the

Aecline of the feudal mode of production and the rise of

‘apitaliem asa dual process involving eis in rural fe:

Gal class relations and rise of towns and their non-feudal

‘lass procestes, But urbanization and the development

fof urban economies was fully as advanced in parts of

‘Africa and Asia as it was in the most advanced parte of

Europe. This applies to commerce, to the rise of a bour

seoisie and working class to the attaining of wuicient

‘2utonomy to allow the development of logal and politica

Systems appropriate to capitalism. There is af course the

theory that European cities were somehow free while

Asian cities were under the tight control of the sur

rounding polity. The principal basis for this view is the

‘ideology of diffusionism which imagines that everything

important in early Burope was imbued with freedom

‘while everything important in Asia (nat to mention Africa)

was ground under “Oriental despotism’ until the

Buropeans came and brought freedom. (Montesquiow and

‘Quesnay believed this, Marx believed it, Weber believed

58. Many believe it today) The so-called roe cities’ of cen

tral Europe were hardly the norm and were no, ia most

cases, crucial forthe rise of capitalism. The partial auton

‘omy of many mereantle-maritime port cities of Europe,

from Italy ta the North Sea, was ofcourse a reality, and

‘usualy reflected either the dominancey the city ofr

‘mall polity (often a city-state) or the gradual

‘Sccommodation of feudal states to their urben sectors,

‘allowing the latter considerable atonomy because of eon

siderations of profit or power. Butall ofthis held trae also

in many cities of Afiea and Asia Small mercantile-mar-

‘time cities and city-states dotted the coasts ofthe Indian

Ocean and the South China Seas like pearls on a string

(as Gupta, 1967; Maleiev, 1984; Simkin, 1968). Within

lange states, mutual accommodation between city and

polity was very common (ax in Mughal India). And in gen-

fra, itappeare that all af the progressive characteristics

ff late-medieval urbanization in Burope were found atthe

fame time in other pars of the hemisphere,

‘Tost before 1492 a slow transition toward eapitalism

was taking place in many regions of Asia, Africa, and

Europe, Ona three continents there were centers ofincp-

fent capitalism, protocapitalism, most of them highly

turbanived, and most of them seaports, Thete provocap-

talist centers, primarily urban bat often with large hin

terlands of commersalized agrienltare (Das Gupta, 1967;

[Nagvi, 1968; Nicholas, 1967-68; Rawaks, 1973), bore var

tous relationships tothe feudal landseapes against which

they abuatted, Some were independent city-states, Some

‘were themselves small (and untesual feudal states-Some

‘rere wholly contained within larger feudal states but had

Sufficient autonomy in matters relating to capitalist enter

prise that the feudal overlordship did not serious cramp

their tye,

‘The mereantile maritime, protocapitalist centers ofthe

astern Hemisphere wore connected tightly with one

another in networks — ultimately a single network —

‘long which flowed material things, people, and ideas

(Blaut, 1976; Abu-Lughod, 1989). The links had been

forged over many centres: come were in place even in

the days when China traded with Rome, By 1492, these

centers were 60 closely interinked thatthe growth and

‘prosperity ofeach of them was highly dependent on that

‘of many others; ultimately, on all of them. By 1492, the

enters had become, in many ways, little capitalist tock

ties. They were seats of production as well as commodi-

ty movement, They held ditinet populations of workers

land bourgeoisie (or proto-bourgeoisie and the worker

‘capitalist relation was very ikely the dominant clas el

tion, They had already developed most ofthe institutions

‘that we ind present in capitalist socety atthe time ofthe

‘bourgeois revolution or revolutions ofthe 17h century

‘They cannot be compared to industrial capitalist societies

of the 19th centary, but then we have to romember that

‘capitalism in Europe went through a long pre-industrial

‘hase, and the deseriptions industrial eaptalism afer,

‘9y, 1800 cannot properly be used to characterize the pre

industrial phase, The centers of 1492 were primarily

‘engaged in moving commodities produced in the sur

‘rounding feudal societies, bt this should not mislead us

{nto thinking of them either as component parts of those

societies or aa being somehow feudal themeelves, on the

‘model of the merchant communities which Nourished

everywhere during the feudal perio.

‘The mall centers. wel asthe large were emitting and

receiving eommodites, technologies, ideas a al sors, pe

ple, in'@ continuous criss-crossing of diffusions (Blast,

1987. It isnot dfficul: to understand that, inspite of

their eutural differences, thet distances from one anoth

er their different political characteristic, their different

aes, they were sharing a eammon process: the gradual

‘ae feapitalism within late feudal society. Thus tis not

stall unreasonable to think of the landscape of rising cap

italim as an even one, stretching from Burope to Africa

fand Asia in pots and nodes, but everywhere atthe same

level of development.

‘Explaining Fourteen Ninety-Two

In 1492, as have seen, capitalism was slowly emerging

and feudalism declining in many parts of Asia, Africa, and

Burope. In that year there would have boen no reason

‘whatever to predict Uhat capitalism would teiumph in

Europe, and would triumph only two centuries later. By

‘the tlumph ofeapitalinm' Tmean the rise of a bourgeoisie

tounguestioned politcal power: the bourgeois revolutions.

"This was really a evolutionary epech, oeeurring through

‘out many European countries at varying rates, but [will

follow convention in dating it symbalically to 1688, the

year of England's ‘Glorious Revolution. Tt should be

Eraphacized that the capitalism which triumphed was not

Sndustrial capitalism, How this pre-industrial eapitalism

shouldbe conceptualized isa diffiult question because it

{s something much larger Uhan the ‘merchant capital’ of

‘medieval times But the industrial revolution didnot ral

Ty begin until the end of the 18th century, and those who

foneeptualize the industrial revelation as simply a con

tinuatio of thebourgecis revolution are noglecting a large

block of history, inside and outside of Burope,

"The explanation for the rise of capitalism to political

power in Europe between 1492 and 1688 requires an

{inderstanding of (1) the reasons why Europeans, not

‘Afficans and Asians, eached und conquered Americs, 2)

‘he reasons why the conquest was sccessful, and () the

rect and indirect effects ofthe 16th-contury plunder of

‘American resources ard exploitation of American workers

on the transformation of Europe, andof I 7dhcentury clo-

tial and semieolonial European enterprise in Ameries,

‘Aftcn, and Asia onthe further transformation of Europe

‘and eventually the political triumph of capitalism inthe

bourgeois revolution, We will summarize each of these

processes in turn

Why America Was Conquered by Europeans

and Not by Africans or Asians

‘One ofthe core myths of Burecentrie diffusionism eon-

cerns the discovery af America Typically it goes something

like this: Europeans, being more progressive, venture-

ome, achievement oriented, and madera than Africans

‘and Asians in the late Mile Age, snd with sperior ch

nology as well as a more advanced economy, went forth to

‘explore and conquer the world. And ao they set sail down,

the African coast in the middle ofthe 15th century and out

teroas the Atlanti to America in 1492. This myth is er

€ial for difusionist ideology fortwo reasons: it explains

the modern expansion of Europe in terms of internal,

immanent forces, and it permits one to acknowledge that

the conquest and its aftermath (Mexican mines, West

Indian plantations, North American settler eolonies, ee)

hhad significance fr European history without at the same

time requiring one to give any eredit in that process to no

Buropeans,

TInreality, the Europeans were doing what everyone ese

was doing woross the hemisphere-wide network of proto

‘capitalist, mereantile maritime centers, and Europeans

hhad no special qualities or advantages, no peculiar ven-

turesomeness, no peculiarly advanced maritime technol

‘ogy, or suchlike. What they did have was opportunity: @

‘altar of locational advantagein the broad senso of aces

‘Sbility, "The point deserves to be put very strongly. Ifthe

‘Western Hemisphere had been mare accessible, say, t0

‘South Indian conte than to Buropean centers, then very

likely India would have become the home of capitalism,

the ate of the bourgeois revolution, and the ruler of the

world,

"In the late Middle Ager, long-distance oceanic voyag-

ing was being undertaken by mereantile-maritime com-

‘munities everywhore. In tho 15th contury, Africans were

sailing to India, Indians to Aftica, Arabs toChina, Chinose

to Africa, and so on (Chaudhuri, 1985; Simkin, 1968)

‘Much of this voyaging was across open ocean and much of

itinvolved exploration, Two non-European examples are

well-known: Cheng Ho's voyages to India and Africa

between 1417 and 1433, and an Indian voyage around the

Cape of Good Hope and apparently some 2000 miles west

‘ward into the Atlantic in ¢1420 Giles, 1872; Ma Huan,

1970; Panikksr, 1959). In this period, the radii of travel

‘wore bocoming longer, asa funetion ofthe general eval:

tion of protocaptallam, the expansion of trade, and the

evelopment of maritime technology. Maritime technolo

{p differed from region to region but no ane region could

be considered to have superiority in any sense implying

evolutionary advantoge (Lewis, 1973;Needham, 1971, vl

4,part3). (There isa widely held but mistaken belief that

Chinese imperial policy prevented merchants from engag-

ing in seaborne trade during the late 16th and early 16th

centuries, On this matter see Pureell, 1965; So, 1975;

‘Wiethoft, 1963. I dieeuss theese in Blast, 1976, note 17)

Certainly the growth of Europe's commercial economy led

to the Portuguese and Spanish voyages of discovery. But

the essence ofthe process was a mattor ofeatching up with

Asian and African provocapitalit. communities by

Buropean communities which were at the margin of the

system and were emerging from a period of downturn rel

live tother parts ofthe system, Iberian Christian states

‘wore in confit with Maghreb states and European mor

chant communities wore having commercial difficulties

both there and in the eastern Mediterranean, The open:

ing of a tea-route to West African gold mining regions,

‘long sailing route known since antiquity and wing mar

‘time technology known to non-Buropeans as well as

Europeans, was obvious strategy. By the late 15th cent

ry the radi of travel had lengthened so that a sea route

{2 India wae found to be feasible (with piloting help fom

Afiean and Indion sailors). The leap aeross the Atlantic

{in 1492 was certainly one ofthe great adventures ofhuman

ae

‘story, But it has to be seen ina context of thared tech:

nological and goographical knowledge, high potential for

commercial sucess, and other factor which place tin &

hhemispherie perspective, as something that could have

been undertaken by non-Europeans just as easily as by

Buropeans,

Buropeans had one advantage. America was vastly

more accessible from Iberian ports than from any extra

Buropean mereantile-maritime centers which had the

capacity for long-distance sea voyages. Accessibility was

inparta matter of sailing distance, Sofala was some 3000

niles farther than the Canary Islands (Columbus! jump:

Sngeoff point) and more than 4000 miles farther from any

densely populated coast with attractive possibilities for

{ade or plunder. The distance from China to America's

northwest coast was even greater, and greater sil othe

ich societies of Mexieo. "To all ofthis we must add the

ting conditions on these various routea, Salling rom the

Tian Ocean into Uhe Atlantic one tails against prevail:

ing winds. The North Pacific is somewhat stormy and

winds are aot reliable. From the Canaries to the West

Indies, onthe other hand, there Blow th trade winds, ad

the return voyage ie made northward ino Uhe westelies,

Obviously an explorer does not have this information at

hhand at the time of the voyage into unknown seas

(although the extent of the goographical knowledge pos-

sessed by Atlantic fishing communities in the 15th ce

‘ny remaina an unanswered and inteiguing question, and

the navigational stratogies employed customarily by

Teerian sailors going to and from the Atlantic islands

would have been similar ta those employed by Columbus

fn erasing the Atlantic: a matter of utiiaing the easter

lies outward and westertes homeward). Te point here is

‘tatter of probabilities, Overall itis vastly more proba

Dlethat an Iberian ship would elfect a passage to America

than would an Aftiean or Asian ship in the late 15th een

tury, and, even ifsuch a voyage were made, itis vastly

‘more probable that Colembue landfill in the West Indies

‘would initiate historical consequences than would have

been the case for an African ship reaching Brazil or a

‘Chinese ship reaching California.

is this environmentalism? There is no more environ

‘mentalism here than there is in, aay, some statement

bout the effect of elfilds on societies ofthe Middle Pas,

Tam atsertng only the environmental conditions which

support and hinder long-distance cceanie travel. In any

tase, if the choice were between an environmentalistic

texplanation and one that claimed fendamental superior

ity of one group overall others, as Eurocentric diffusion

fam doce, woald we not settle fr environmentalism?

‘Before we leave this topic, there remain two important

questions, First, why did not West Afticans discover

‘America since they were even closer tot than the Tberians

‘were? The answer seems tobe that mereentil, protocap,

Italist centers in West and Central Africa ware not oF

tented to commerce by son (as were those of East Aftiea)

"The great long-distance trade route lod across the Suda

tothe Nile and the Middle Bast, across the Sahara to the

Maghreb and the Mediterranean, ete. Sea trade existed all

‘slong the western coast, hut apparently it was net impor

tant given that civilizations were mainly inland and trad

ing partners lay northward and eastward ee Devisse and

bib, 1984). Second, why didnot the trading ctes ofthe

Maghreb discover America? This region (as thn Khaldun

noted not long before) was in a politcal and commereial

Slump, In 1492 it was under pressure from the Tberians

fand the Turks, Just at that historical conjuncture, this

Fegion lacked a eapacity for major longdistance oceanic

voyaging

Why the Conquest Was Successful

‘America became significant in the rise of Burope, and

the rise of capitalism, soon after the fist contact in 1492.

Immediately a process bogon, and explosively enlarged,

involving the destruction of American states and cviliza

tons, the plunder of precious metals, the exploitation of

labour, and the occupation of American lands by

Europeans. fweare to understand the impact ofall ofthis

‘on Burope (and capitalism), wo have to understand how