Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

(Wells, 2008) Suprapubic or Urethral Catheter What Is The Optimal Method of Bladder Drainage After Radical Hysterectomy

Transféré par

dadupipaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

(Wells, 2008) Suprapubic or Urethral Catheter What Is The Optimal Method of Bladder Drainage After Radical Hysterectomy

Transféré par

dadupipaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

GYNAECOLOGY

GYNAECOLOGY

Suprapubic or Urethral Catheter:

What Is the Optimal Method of Bladder

Drainage After Radical Hysterectomy?

Tiffany H. Wells, MD, FRCSC,1 Helen Steed, MD, FRCSC,1,2 Valerie Capstick, MD, FRCSC,1,2

Alexandra Schepanksy, MD, FRCSC,1,2 Michelle Hiltz, MSc,1 Wylam Faught, MD, FRCSC1,2

1

University of Alberta, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Edmonton AB

2

Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Cross Cancer Institute, Edmonton AB

Abstract été utilisé pour la vidange postopératoire de la vessie à la suite

d’une HAR, le cathétérisme suspubien (CSP) constitue une

Background: Lower urinary tract dysfunction is a common morbidity méthode de rechange pouvant être avantageuse.

related to radical hysterectomy (RAH). Although transurethral

catheterization (TUC) has traditionally been used for postoperative Objectifs : Déterminer, au moyen d’une étude de cohorte

bladder drainage following RAH, suprapubic catheterization (SPC) rétrospective, l’incidence de l’infection des voies urinaires (IVU), la

is an alternative method that may be advantageous. durée de l’hospitalisation postopératoire et le délai avant l’essai de

miction chez les femmes ayant fait l’objet d’un cathétérisme

Objectives: To determine, by means of a retrospective cohort study,

suspubien ou transurétral à la suite d’une HAR motivée par un

the incidence of urinary tract infection (UTI), duration of

cancer du col utérin de stade précoce.

postoperative hospital stay, and time to trial of voiding in women

catheterized suprapubically or transurethrally after RAH for early Méthodes : Deux cent douze patientes ayant subi une HAR et une

stage cervical cancer. stadification, en présence de cancers du col utérin de stades

Methods: Two hundred twelve patients who underwent RAH and IA1 + LVS, 1A2 et 1B1 à Edmonton entre 1996 et 2006, ont

staging for stage IA1 + LVS, 1A2, and 1B1 cancer of the cervix in participé à l’étude. Trois gynécologues-oncologues ont effectué

Edmonton between 1996 and 2006 were included in the study. les chirurgies en question. Des données opératoires,

Three gynaecologic oncologists performed the surgeries. postopératoires et démographiques ont été tirées des dossiers de

Operative, postoperative, and demographic data were extracted ces patientes. Les patientes ont fait l’objet d’un cathétérisme

from patient records. Patients were catheterized either suspubien (groupe CSP) ou transurétral (groupe CTU), à la

suprapubically (SPC group) or transurethrally (TUC group) discrétion du chirurgien. Des essais comparatifs et une analyse de

according to the surgeon’s discretion. Comparative tests and régression multivariée ont été utilisés pour comparer certains

multivariate regression analysis were used to compare outcome critères d’évaluation entre les groupes et pour neutraliser l’effet

measures between the groups and to adjust for confounding des variables confusionnelles.

variables. Résultats : Le groupe CTU comptait une proportion de patientes

Results: The TUC group had a higher proportion of patients with UTI présentant une IVU (27 %) plus élevée que celle que comptait le

(27%) than the SPC group (6%) (P < 0.001). The SPC group had groupe CSP (6 %) (P < 0,001). Les participantes du groupe CSP

a shorter postoperative hospital stay (4.8 vs. 5.7 days; P < 0.001) ont connu une hospitalisation postopératoire plus courte

and an earlier trial of voiding (2.7 vs. 4.4 days; P < 0. 001). (4,8 jours, par comparaison avec 5,7 jours; P < 0,001) et un essai

Following regression analysis, statistically significant differences de miction plus précoce (2,7 jours, par comparaison avec

remained for UTI and time to initiation of a trial of voiding. 4,4 jours; P < 0,001). À la suite de l’analyse de régression, nous

constations toujours des différences significatives sur le plan

Conclusion: After RAH for early stage cervical cancer, suprapubic

statistique en matière d’IVU et de délai avant la mise en œuvre

catheterization is associated with a lower rate of UTI and an

d’un essai de miction.

earlier trial of voiding than transurethral catheterization.

Conclusion : À la suite d’une HAR motivée par un cancer du col

Résumé utérin de stade précoce, le cathétérisme suspubien est associé à

un taux moindre d’IVU et à la tenue plus précoce d’un essai de

Contexte : Le dysfonctionnement des voies urinaires basses est une miction, par comparaison avec le cathétérisme transurétral.

morbidité courante associée à l’hystérectomie radicale (HAR).

J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2008;30(11):1034–1038

Bien que le cathétérisme transurétral (CTU) ait traditionnellement

INTRODUCTION

Key Words: Radical hysterectomy, suprapubic catheter, urinary

tract infection, urinary bladder urgery is commonly used in treatment for women with

Competing Interests: None declared. S early cervical cancer (stages IA and IB1) who have mini-

Received on August 27, 2007 mal medical comorbidity. Urinary dysfunction is the most

Accepted on February 4, 2008 common morbidity related to radical hysterectomy,

1034 l NOVEMBER JOGC NOVEMBRE 2008

Suprapubic or Urethral Catheter: What Is the Optimal Method of Bladder Drainage After Radical Hysterectomy?

occurring postoperatively in approximately 30% of RAH All patients were administered antibiotics preoperatively

patients.1–3 The majority of these women will experience and were catheterized intraoperatively, either

acute neurogenic bladder dysfunction during the postoper- transurethrally (using a Foley catheter with 16 French

ative period, with difficulty in voiding, high post-void resid- gauge, 5.3 mm diameter) or suprapubically (using a

ual volumes, and changes in bladder compliance. Perivesical Bonanno catheter with 14 British gauge, 2.1 mm diameter).

edema, hematoma, fibrosis, and autonomic denervation of Exclusion criteria for the study were an incomplete medical

the bladder may contribute to this postoperative urinary chart, incorrect surgical coding, intraoperative cystotomy or

dysfunction after RAH, but the pathophysiology of postop- ureteric injury, RAH at the time of Caesarean section, RAH

with PLN for malignancy other than cervical, and a past

erative urinary dysfunction remains incompletely under-

history of pelvic radiotherapy.

stood.4,5 Despite the frequency of occurrence of urinary

dysfunction following RAH, no consensus exists on its Demographic data including patient age, parity, history of

appropriate management in the postoperative period. CS, and stage of disease were obtained from health records.

Transurethral catheterization has traditionally been used to Maximum tumour dimension and tumour histology were

facilitate postoperative bladder drainage following RAH, retrieved from surgical pathology reports. Operative data,

but suprapubic catheterization is an alternative method that including surgeon’s name, operating time, and estimated

may have distinct advantages. Possible benefits of SPC over blood loss, were recorded from operative records. Our out-

TUC include earlier spontaneous voiding, improved facili- comes of interest (the incidence of UTI, LOHS, and time to

TOV) were extracted from the medical records.

tation of voiding trials, improved patient comfort,

decreased incidence of urinary tract infection, earlier ambu- Patients were assigned to one of two groups on the basis of

lation, and shorter duration of hospital stay.6,7 the method of catheterization used at the time of surgery.

We hypothesized that SPC after RAH and pelvic The method of catheterization was determined solely by the

lymphadenectomy for early stage cervical cancer is associ- surgeon’s preference. Demographic data and operative data

ated with a decreased incidence of UTI, a shorter length of were compared between groups to determine whether the

hospital stay and an earlier postoperative trial of voiding two groups differed significantly other than in mode of

when compared with TUC. catheterization. Outcomes of interest, including incidence

of UTI, LOHS, and time to TOV, were compared between

MATERIALS AND METHODS the two groups. A UTI was documented if a patient had

dysuria and a positive urine dipstick test (for leucocytes and

We performed a retrospective cohort study using the nitrites), a urine culture with >105 CFU/mL, microscopy

records of women with stage IA1 + LVSI, 1A2, and IB1

with ³ 5 leukocytes/high power field, or if a patient was

cervical cancer who had RAH and PLN performed in

treated for a UTI. All UTIs between the time of surgery and

Edmonton, Alberta, between January 1996 and March

the six-week follow-up visit were recorded. Universal

2006. In all cases, a type II RAH and PLN was performed

screening for UTIs in the postoperative period is not per-

by one of three gynaecologic oncologists, assisted by gynae-

formed in our institution; only patients with symptoms

cology residents. Each type II RAH included resection of

were investigated. LOHS was the total number of days

the cervicovesical fascia, the proximal uterosacral and

from admission to discharge. Time to initiation of trial of

rectovaginal ligaments, a portion of the upper vagina, and

voiding was defined as the number of days from insertion

the medial half of the parametria and cardinal ligaments.

of catheter to first voiding attempt (discontinuation of TUC

or clamping of SPC). The actual timing of TOV was deter-

ABBREVIATIONS mined by the individual surgeon. Transurethral catheters

were removed as early as the second postoperative day or as

CFU colony forming unit

late as the seventh postoperative day. Suprapubic catheters

CS Caesarean section were commonly clamped to begin TOV on the second

EBL estimated blood loss postoperative day, but in some cases were clamped later.

LOHS length of hospital stay

PLN pelvic lymphadenectomy

The chi-square test, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel’s row mean

RAH radical hysterectomy

score statistic, and Wilcoxon rank-sum test (non-

parametric) were used for analysis of categorical parame-

SPC suprapubic catheterization

ters, ordinal response variables, and continuous measures,

TOV trial of voiding

respectively. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for

TUC transurethral catheterization

all tests. Regression analysis was performed to adjust for

UTI urinary tract infection

confounding variables that were estimated to have the most

NOVEMBER JOGC NOVEMBRE 2008 l 1035

GYNAECOLOGY

Table 1. Patient characteristics

TUC (n = 134) SPC (n = 78) P

Median age, years (range) 40.00 (20–78) 40.50 (21–78) 0.939

Median parity (range) 2.00 (0–9) 2.00 (0–7) 0.817

Previous CS, % (n) 15.9 (21) 6.4 (5) 0.043

FIGO Stage, % (n)

IA 46.3 (62) 42.3 (33) 0.576

IB 53.7 (72) 57.7 (45)

Median tumour size, mm (range) 3.0 (0–60) 5.0 (0–60) 0.382

Histology, % (n)

Squamous 51.5 (69) 44.9 (35) 0.455

Adeno 29.8 (40) 29.5 (23)

Other 18.7 (25) 25.6 (20)

Table 2. Operative information

TUC (n = 134) SPC (n = 78) P

Surgeon

A 46% (62) 0% (0) < 0.001

B 37% (49) 100% (78)

C 17% (23) 0% (0)

Median operative time, minutes (range) 187 (89–318) 169 (105–295) 0.016

Median estimated blood loss, mL (range) 600 (200–6000) 500 (200–2300) 0.094

effect on each outcome of interest. Adjusted odds ratios proportion of patients in the TUC group had undergone

were calculated for binary responses using logistic regres- previous CS than in the SPC group (15.9% vs. 6.41%; P =

sion analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using 0.043) (Table 1). Significantly more patients in the SPC

SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC). group than in the TUC group had surgery performed by

surgeon B. Initially, all three surgeons used TUC only; in

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the

2000, surgeon B switched to use of SPC exclusively. The

Research Ethics Board of the Cross Cancer Institute and

SPC group was associated with a shorter operative time

the University of Alberta.

than the TUC group (median = 169 vs. 187 minutes; P =

0.016). There was no significant difference in EBL between

RESULTS

groups (Table 2).

Of 264 patients identified through surgical coding logs, 212

met the inclusion criteria. Of the excluded patients, 24 had A significantly higher proportion of patients in the TUC

malignant pathology other than cervical, 12 had a procedure group developed UTI than in the SPC group (27% vs. 6%;

other than RAH with PLN, five had preoperative radiother- P = 0.003). The median LOHS was significantly shorter in

apy, four had medical records that could not be located, the SPC group than in the TUC group (4 days vs. 6 days; P <

three had cancer staging > IB1, two had RAH at the time of 0.001), and median time to initiation of TOV was also

CS, and two had intraoperative cystotomy. shorter in the SPC group (3 days vs. 4 days; P < 0.001)

(Table 3).

There were 134 patients in the TUC group and 78 patients

in the SPC group. Baseline characteristics, including age, Multivariate regression analysis was used to adjust for con-

parity, stage of disease, maximum tumour dimension, and founding variables. After correcting for surgeon, operative

histology did not differ between groups. In each group, time, and tumour size through multivariate analysis, the

patients with tumour diameters greater than 4.0 cm had relationship between the occurrence of UTI and the type of

been clinically staged as IB1, only to be found to have larger catheter used remained statistically significant (OR 0.12;

tumours at the time of pathology examination. A greater 95% CI 0.039 to 0.369, P = 0.002). If a patient was

1036 l NOVEMBER JOGC NOVEMBRE 2008

Suprapubic or Urethral Catheter: What Is the Optimal Method of Bladder Drainage After Radical Hysterectomy?

Table 3. Outcomes by method of catheterization

TUC (n = 134) SPC (n = 78) P

Urinary tract infection (n) 27% (36) 6% (5) 0.003

Median length of hospital stay, days (range) 6 (3–16) 4 (3–12) < 0.001

Median time to trial of voiding, days (range) 4 (2–7) 3 (2–5) < 0.001

catheterized transurethrally, the risk of developing a UTI incidence of UTI in the TUC group was significantly higher

was eight times greater than if the patient was catheterized than in the SPC group (35% vs. 6%; P < 0.001). This is

suprapubically. The difference in time to initiation of TOV important to note, because analyzing the outcomes for only

between the two study groups remained statistically signifi- one surgeon’s patients, although limiting generalizability,

cant (P < 0.001) after adjusting for surgeon, parity, tumour controls for the unmeasured surgical and postoperative

size, and previous CS. Operative date was chosen as a con- differences in care between physicians.

founder for LOHS because in 2000 the surgeons at our

institution began earlier postoperative feeding, resulting in The outcomes and variables we were able to study are lim-

earlier hospital discharge and shorter LOHS. After adjust- ited by the retrospective data collection. Despite this meth-

ing for surgeon, whether or not surgery was done before or odology, we were able to document any UTI up to six weeks

after 2000, and tumour size, the median LOHS was not after RAH and PLN, and conclude that any UTI detected

significantly different between the groups. after this point was not catheter-associated. LOHS,

although easily measured, is dependent on multiple vari-

DISCUSSION ables that cannot easily be controlled in retrospective

reviews. We were not able to show a difference in LOHS

This retrospective study assessed whether the method of

between groups when all patients were analyzed. However,

catheterization used postoperatively affected the incidence

in surgeon B’s patients, LOHS was significantly shorter in

of UTI, time to trial of voiding, and length of hospital stay.

the SPC group than in the TUC group, suggesting that the

Although a retrospective design may result in selection bias,

surgeon may not be the most important factor in determin-

most patient demographic and operative variables were

ing patients’ LOHS. Time to TOV is undeniably linked to

similar in the women catheterized suprapubically and those

method of catheterization because surgeons are more likely

catheterized transurethrally. We acknowledge, however,

to start an early trial of voiding in patients with an SPC. The

that significantly more women in the TUC group than

success of first TOV would be a more useful parameter to

women in the SPC group had a previous CS. It is plausible

compare between groups, but this was not consistently

that this difference and the resulting difficulty of bladder

recorded. A prospective study design would allow for more

dissection may have influenced the type of catheter chosen

outcomes to be evaluated and compared over a greater

by the surgeon or the timing of a postoperative voiding trial.

length of time. Valuable outcomes that could not be

Furthermore, a longer operative time may indicate that the

extracted retrospectively, such as patient satisfaction,

procedure was more difficult or involved a larger tumour,

mechanical difficulties with SPC, complications secondary

and these variables may also have influenced a surgeon in

to SPC insertion, likelihood of successful TOV with each

the choice of catheter. However, after regression analysis

method of catheterization, total duration of catheterization,

that adjusted for surgeon, operative time, and tumour size,

and long-term voiding dysfunction, would be important to

the difference between groups in the incidence of UTI and

include in a prospective study design.

time to TOV remained significant.

In this study only one surgeon (surgeon B) used SPC. This Although the benefits of SPC use have been demonstrated

surgeon initially used TUC only, but after learning of the in urogynaecology and general surgery patients,6–13 only

utility of SPC in urogynaecology procedures changed to the three studies evaluating the use of SPC after RAH and PLN

exclusive use of SPC. Despite regression analysis that con- have been published. Naik et al. reported a higher incidence

trols for surgeon, it is difficult to determine if the differ- of UTI on the third postoperative day in patients who were

ences in outcomes were related to the surgeon involved or performing intermittent self-catheterization than in patients

the mode of catheterization. To better control for this con- with SPC (42% and 18%, respectively),14 and van Nagell et

founder, we analyzed patients of surgeon B only. Surgeon al. described a 44% rate of UTI in patients with TUC com-

B’s patients with TUC had a significantly longer postopera- pared with 23% in patients with SPC.15 A small study (N =

tive stay than patients with SPC ( P < 0.001) and the 24) reported by Nwabineli et al. found no difference in the

NOVEMBER JOGC NOVEMBRE 2008 l 1037

GYNAECOLOGY

incidence of UTI after RAH and PLN between women 5. Jackson KS, Naik R. Pelvic floor dysfunction and radical hysterectomy. Int

J Gynecol Cancer 2006;16:354–63.

with TUC and with SPC.16 Our findings are consistent with

6. Schiøtz HA, Malme PA, Tanbo TG. Urinary tract infections and

previous reports, and further demonstrate the benefit of asymptomatic bacteriuria after vaginal plastic surgery. A comparison of

using SPC through a reduction in postoperative catheter suprapubic and transurethral catheters. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand

1989;68(5):453–5.

associated infection. We have demonstrated for the first

time the earlier initiation of a voiding trial associated with 7. Bergman A, Matthews L, Ballard CA, Roy S. Suprapubic versus

transurethral bladder drainage after surgery for stress urinary incontinence.

SPC after RAH and PLN. Obstet Gynecol 1987 Apr;69(4):546–9.

We recognize that a growing proportion of radical hysterec- 8. McPhail MJ, Abu-Hilal M, Johnson CD. A meta-analysis comparing

tomies are being performed laparoscopically, and that RAH suprapubic and transurethral catheterization for bladder drainage after

abdominal surgery. Br J Surg 2006 Sep;93(9):1038–44.

patients are likely to be discharged early from hospital

9. Baan AH, Vermeulen H, van der Meulen J, Bossuyt P, Olszyna D, Gouma

regardless of method of catheterization. However, we sug- DJ. The effect of suprapubic catheterization versus transurethral

gest that the use of SPC rather than TUC in this group catheterization after abdominal surgery on urinary tract infection: a

randomized controlled trial. Dig Surg 2003;20(4):290–5.

would also result in a lower incidence of UTI and an early

TOV after hospital discharge. 10. Andersen JT, Heisterberg L, Hebjørn S, Petersen K, Stampe Sørensen S,

Fischer-Rasmussen W, et al. Suprapubic versus transurethral bladder

drainage after colposuspension/vaginal repair Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand

CONCLUSION 1985;64(2):139–43.

In women who have had radical hysterectomy and pelvic 11. Perrin LC, Penfold C, McLeish A. A prospective randomized controlled trial

lymphadenectomy for early stage cervical cancer, use of a comparing suprapubic with urethral catheterization in rectal surgery. Aust N

suprapubic catheter is associated with a significantly lower Z J Surg 1997 Aug;67(8):554–6.

incidence of UTI and an earlier trial of voiding than use of a 12. Schiøtz HA, Malme PA, Tanbo TG. Urinary tract infections and

asymptomatic bacteriuria after vaginal plastic surgery. A comparison of

transurethral catheter.

suprapubic and transurethral catheters. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand

1989;68(5):453–5.

REFERENCES

13. Shapiro J, Hoffmann J, Jersky J. A comparison of suprapubic and

1. Naik R, Nwabinelli J, Mayne C, Nordin A, de Barros Lopes A, Monaghan transurethral drainage for postoperative urinary retention in general surgical

JM. Prevalence and management of (non-fistulous) urinary incontinence in

patients. Acta Chir Scand 1982;148(4):323–7.

women following radical hysterectomy for early stage cervical cancer. Eur J

Gynaecol Oncol 2001;22:26–30. 14. Naik R, Maughan K, Nordin A, Lopes A, Godfrey KA, Hatem MH. A

2. Parkin DE. Lower urinary tract complications of the treatment of cervical prospective randomised controlled trial of intermittent self-catheterisation

carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1989;44:523–9. vs. suprapubic catheterisation for post-operative bladder care following

3. Bandy LC, Clarke-Pearson DL, Soper JT, Mutch DG, MacMillan J, radical hysterectomy. Gynecol Oncol 2005; 99:437–42.

Creasman WT. Long-term effects on bladder function following radical 15. van Nagell JR, Penny RM, Roddick JW. Suprapubic bladder drainage

hysterectomy with and without postoperative radiation. Gynecol Oncol

following radical hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1972;113(6):849–50.

1987;26:160–8.

4. Kindermann G, Deus-Thiede G. Postoperative urological complications 16. Nwabineli NJ, Walsh DJ, Davis JA. Urinary drainage following radical

after radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. Baillieres Clin Obstet hysterectomy for cervical carcinoma—a pilot comparison of urethral and

Gynaecol 1988;2:933–41. suprapubic routes. Int J Gynecol Cancer 1993;3:208–10.

1038 l NOVEMBER JOGC NOVEMBRE 2008

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Année Prépa Electricité, Deuxième PartieDocument221 pagesAnnée Prépa Electricité, Deuxième PartieAbdelkader Faklani DouPas encore d'évaluation

- Geometrie Pour Dao2 PDFDocument161 pagesGeometrie Pour Dao2 PDFlekouf43100% (1)

- ANNONCES ASSISTANTS MATERNELS-Disponibilités Secteur Lyautey Du 12 Juin 2020Document3 pagesANNONCES ASSISTANTS MATERNELS-Disponibilités Secteur Lyautey Du 12 Juin 2020younes amaraPas encore d'évaluation

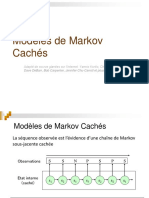

- 3 - Modeles de Markov CachesDocument34 pages3 - Modeles de Markov CachesWISSALPas encore d'évaluation

- GISEMENTDocument4 pagesGISEMENTTouré AbdoulPas encore d'évaluation

- TP 1Document1 pageTP 1djennati100% (1)

- Unite 71 Manuel OpératoireDocument110 pagesUnite 71 Manuel OpératoireAbdessalem Bougoffa50% (2)

- PdM3 Guide Corrige Vrac Repros C4Document2 pagesPdM3 Guide Corrige Vrac Repros C4Eva BteichPas encore d'évaluation

- TD6 PhysiqueDocument4 pagesTD6 PhysiqueEric DeumoPas encore d'évaluation

- Corrige TD 8 1920 2Document5 pagesCorrige TD 8 1920 2friends diaryPas encore d'évaluation

- Api RestDocument8 pagesApi RestfogoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ajust ExpoDocument4 pagesAjust ExpoMme_Sos100% (1)

- ChapitreDocument8 pagesChapitreAchour IfrekPas encore d'évaluation

- Serco FDocument26 pagesSerco FRV PenrroiPas encore d'évaluation

- CC 1 Analyse Natalia Borbón TorresDocument3 pagesCC 1 Analyse Natalia Borbón TorresNatalia Borbon TorresPas encore d'évaluation

- Cours ExcelDocument80 pagesCours ExcelLahcen Boufouss100% (1)

- NF EN 1431 (Mai 2009)Document19 pagesNF EN 1431 (Mai 2009)Fatima BouhajaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sujet Bac 2023 Guinee Niger MathsDocument5 pagesSujet Bac 2023 Guinee Niger Mathsmr.4chiffrePas encore d'évaluation

- TP Conduction CompletDocument10 pagesTP Conduction Complethamza layachi75% (4)

- TD Regime de Neutre TTDocument4 pagesTD Regime de Neutre TTOlivier FLOHRPas encore d'évaluation

- Cours Lignes de Transmission Séance Adaptation D'impédance 2011 2012Document8 pagesCours Lignes de Transmission Séance Adaptation D'impédance 2011 2012benlamlihPas encore d'évaluation

- Poly JavaDocument176 pagesPoly JavaLeonzoConstantiniPas encore d'évaluation

- FeuilletageDocument25 pagesFeuilletageLē JøkērPas encore d'évaluation

- W - 250 - 275 - 325 - 350 - 400 - 1 K..p..Document28 pagesW - 250 - 275 - 325 - 350 - 400 - 1 K..p..joviadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Howto L3 IntervlanroutingDocument7 pagesHowto L3 IntervlanroutingWilford ToussaintPas encore d'évaluation

- GPM Tle C 3e Edition.Document258 pagesGPM Tle C 3e Edition.Pierrot Jules AMOUSSOU100% (2)

- Exercices Chapitre 3 FractionsDocument3 pagesExercices Chapitre 3 FractionsTony GRACAPas encore d'évaluation

- DS SDM S1 2015 CorrectionDocument2 pagesDS SDM S1 2015 CorrectiondsiscnPas encore d'évaluation

- Algèbre 1 V. Def 2017-2018Document141 pagesAlgèbre 1 V. Def 2017-2018Alexis Rosuel100% (1)

- Rapport Optimisation Sur MatlabDocument13 pagesRapport Optimisation Sur MatlabLino YETONGNONPas encore d'évaluation