Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Regulatory Focus On Risky Decision-Making.

Transféré par

kishta1Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Regulatory Focus On Risky Decision-Making.

Transféré par

kishta1Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

APPLIED PSYCHOLOGY: AN INTERNATIONAL REVIEW, 2008, 57 (2), 335359 doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00319.

BRYANT RISKY UK OriginalDECISION-MAKING Applied Psychology, 2008 XXX International Association 0269-994X Applied Publishing APPS Articles Oxford, Psychology Ltd Blackwell AND DUNFORD for

The Influence of Regulatory Focus on Risky Decision-Making

Peter Bryant* and Richard Dunford

Macquarie Graduate School of Management, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

Although studies show that regulatory focus influences decision making and risk taking, theories of risky decision making typically conflate different regulatory orientations and the related distinctions between the positive and negative risks associated with acts of omission and commission. In contrast, we argue that different regulatory orientations influence risk perception and risk propensity in different ways and underpin complex emotional responses in risky decision making. We propose a new model of these processes and suggest that regulatory focus may be important in priming and managing risk taking behavior. We conclude by discussing implications for research and practice. Bien que des recherches montrent que le centre de rgulation influence la prise de dcision et la prise de risque, les thories de la prise dcision risque regroupent habituellement diffrentes formes de rgulation et les distinctions connexes entre les risques positifs et ngatifs associs au passage lacte ou non. Contrairement ces thories, nous avanons que les diffrentes formes de rgulation influencent la perception et la propension au risque selon diffrentes modalits et sous-tendent les rponses motionnelles complexes dans la prise de dcision risque. Nous proposons un nouveau modle de ces processus et suggrons que le centre de rgulation peut tre important dans lamorce et la gestion du comportement de prise de risque. Nous concluons en discutant des implications de ces rsultats pour la recherche et la pratique.

INTRODUCTION

In classically inspired studies of decision-making, risk is related to Bayesian ideals of probability and expected utility (March & Shapira, 1987; Simon, 1979). In such a world, people have sufficient information and cognitive

* Address for correspondence: Peter Bryant, Macquarie Graduate School of Management, Macquarie University, Sydney NSW 2109, Australia. Email: Peter.Bryant@mq.edu.au The authors express their gratitude to David Gow and the anonymous reviewers for the 2007 Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management for valuable suggestions on earlier versions of this paper. 2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology. Published by Blackwell Publishing, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

336

BRYANT AND DUNFORD

capacity to arrive at fully objective measures of risk and then make decisions to maximise utility (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). However, in more recent times, concepts of limited information, bounded rationality, and the acknowledgement of psychosocial factors have redrawn the map of risk research (Camerer & Loewenstein, 2004; Schwartz, 2002). Scholars now incorporate psychological and sociological factors into models of risky decision-making (Slovic, 2000a). This perspective has prompted Richard Thaler (2000, p. 140) to predict that Homo Economicus will evolve into Homo Sapiens, noting that economic behavior and decision-making involve a wide range of human characteristics, not simply the pursuit of utility maximisation. Researchers have thus uncovered more of the internal complexities associated with risk-taking. It is no longer seen as a single unitary process, where people make objective assessments of probabilities based on complete information. Rather, people possess general propensities to accept or avoid risks, perceive and assess risks based on subjective criteria, make idiosyncratic trade-offs between risk and reward in decisionmaking (Bazerman, 2001), and consistently employ decision heuristics defined as cognitive short-cuts (Camerer & Loewenstein, 2004). Behavioral approaches to the study of decision-making thus incorporate psychosocial factors into the analysis of risk. Among the important psychosocial antecedents of risk-taking are the dispositions and biases of the individual decision-maker, the characteristics of the organisational context, and the nature of the decision problem itself (Beach & Connolly, 2005). However, it is virtually impossible to explore all such factors simultaneously. Rather, recent research focuses on hitherto unexplored social and psychological factors in order to uncover their role in risk-taking. Working in this vein, scholars have identified additional antecedents of risky decision-making, for example, the influence of interpersonal relationship trust (Das & Teng, 2004), the escalation of commitment (Wong, 2005), the psychological factors which influence heuristic bias (Gilovich & Griffin, 2002), and the influence of affect on risk perception and risk propensity in complex strategic decision-making situations (Mittal & Ross, 1998). Scholars recommend further research on related factors including social cognitive self-regulation (Higgins, 2002; Mischel & Shoda, 1998; Sitkin & Weingart, 1995), which is the focus of this paper. Self-regulation is an important topic in the study of social cognition, which is distinguished from non-social cognition by its focus on the interaction between social and cognitive variables (Higgins, 2000b). Social cognition underlies learning about what matters in the social world and thereby provides essential aspects of what it means to be human. In this context, self-regulation is broadly defined as a systematic process of human thought and behavior that involves setting personal goals and steering oneself toward the achievement

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

RISKY DECISION-MAKING

337

of those goals (Boekaerts, Maes, & Karoly, 2005). Self-regulation also includes regulatory focus, which refers to the fundamental concerns that guide self-regulation and underpin motivation systems (Higgins, 2002). Regulatory focus influences goal-directed thought and behavior, and is expressed as either a promotion focus on attaining gains, or a prevention focus on avoiding losses. Studies already demonstrate the impact of regulatory focus on risky decision-making (Higgins, 2002), risky information processing style (Frster, Higgins, & Bianco, 2003), outcome categorisation under conditions of uncertainty (Molden & Higgins, 2004) and probability weighting bias (Kluger, Stephan, Ganzach, & Hershkovitz, 2004). This paper probes these phenomena more deeply. The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. The next section presents a brief review of theories about risky decision-making, self-regulation and regulatory focus theory. This is followed by the development of a set of propositions that identify the role of regulatory focus in risky decisionmaking. In particular, the paper argues that regulatory focus influences the effect of outcome history on risk propensity and influences the effect of problem framing on risk perception (see Baron & Kenny, 1986; Sitkin & Pablo, 1992). The paper also argues that regulatory focus underpins emotional responses in risky decision-making (see Higgins, Grant, & Shah, 1999; Liberman, Idson, & Higgins, 2005). It concludes by discussing the implications for future research and practice.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Theories of Risk

From a behavioral perspective, risk has been defined as the extent to which there is uncertainty about whether potentially significant and/or disappointing outcomes of decisions will be realized (Sitkin & Pablo, 1992, p. 10). This reference to uncertainty and disappointment highlights the psychosocial factors involved in the behavioral conception of risk. In this conception, risk is a socially constructed estimation of probability, rather than an objective reality of the world (Slovic, 2000b). Decisions are riskier if the expected outcomes are seen as more uncertain, the desired goals as more difficult to achieve, or the potential outcomes include extreme consequences (Sitkin & Pablo, 1992). This approach is consistent with the assumed relevance of social cognitive factors such as regulatory focus in risk-taking. In this paper, we adopt the same approach and define risk as the socially constructed estimation of the chance of some occurrence or outcome. A similar conception of risk underpins the identification of the individual and social antecedents that influence risky decision-making. In particular, the decision-makers situational context and prior experience or familiarity

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

338

BRYANT AND DUNFORD

with classes of problem situations act as determinants of risky decisionmaking. Indeed, when decision-makers are more experienced, they may begin to focus selectively on the evidence of their past ability to overcome obstacles, and therefore may be willing to accept risks that less experienced individuals would avoid (e.g. March, 1997). Escalation of commitment is also consistent with the notion that individual experiences foster increasingly risky behavior over time (Geiger, Robertson, & Irwin, 1998; Wong, 2005). Situational factors have been also observed in relation to different aspects of managerial risk-taking (Krueger & Dickson, 1994; Pablo, Sitkin, & Jemison, 1996). In summary, a persons situation and accumulated experiences have a significant influence on risk-taking. These factors are related to risk perception and risk propensity as psychosocial dimensions of risk-taking. Risk propensity is defined as the willingness to take risks, while risk perception is defined as the assessment of the risk inherent in a situation (Sitkin & Pablo, 1992). These factors are prominent in behavioral theories of risk that recognise the influence of organisational context, the problem situation, and an individuals psychological and social characteristics. Most notably, Sitkin and Pablo (1992) propose a mediated model of risk-taking, theorising that the effects of a number of previously examined variables on risk-taking are not direct, but instead are mediated by risk propensity and risk perception. They argue that the effects of problem framing and outcome history on risk-taking are mediated by risk perception and risk propensity, respectively. These relationships had been overlooked and confounded in prior studies. Subsequent empirical studies provide supporting evidence for these claims (Sitkin & Weingart, 1995). These findings have major implications for practice. First, they suggest that risk-taking is more malleable early in a decision-makers domain career when he or she has little experience in a particular risk domain. Then, as domain experience increases over time, risk propensity will tend to become more stable, supporting the point made by socialisation theorists about the relative malleability of inexperienced versus experienced actors (March, 1997). This finding is supported by those who question the validity of investigating risk devoid of situational context in hypothetical situations (Kuhberger, Schulte-Mecklenbeck, & Perner, 2002). Second, individual or group decision makers can be purposively selected on the basis of their outcome histories and risk propensity to influence the likelihood that more or less risky decisions will be made (Sitkin & Weingart, 1995, p. 1589). This contradicts the view that risk perception and propensity are stable traits. Regarding risk perception, Kahneman and Tversky (1979) established the importance of problem framing as a situationally conditioned variable. In a series of seminal studies, they show that how a particular risk is framed has a major impact on how prospects are perceived (Kahneman & Tversky, 2000a; Tversky & Kahneman, 1986). However, if risk perceptions are not

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

RISKY DECISION-MAKING

339

further examined, it is unclear how problem framing affects decisionmaking in actual contexts (Sitkin & Weingart, 1995). It is especially important to identify if a problem is framed as a positive risk or as a negative risk. In that regard, Sitkin and Weingart (1995) argue that downside risks become more salient in positively framed situations (inducing risk-avoidance behavior), whereas upside risks become more salient in negatively framed situations (inducing risk-seeking behavior). Building on these insights, Mittal and Ross (1998) further show that positive affect is associated with positive risk framing, while negative affect is associated with negative risk framing. Collectively, these findings imply that the way in which problem situations are framed will have a significant impact on how risks are perceived and felt. Similar issues arise in relation to the determinants of risk propensity. Most earlier studies focus on either individual risk orientation as a personality variable or on objective assessments of risk, and largely ignore the role of a persons previous risk outcome history and situational context (e.g. Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). Sitkin and Weingart (1995) challenge this a-historical approach, and their studies confirm that prior success in taking risks within a particular problem domain can increase the propensity to take future risks in that domain (cf. Krueger & Dickson, 1994). Consequently, they argue that experiential factors must be included in any analysis of risk propensity (cf. Sitkin & Weingart, 1995). These findings contradict the view that risk propensity is a stable personality trait and suggests that a persons willingness to take risks is significantly dependent on their prior experience of risktaking. These findings also counter the persistent bias of many studies, which tend to sanitise decision-making and risk-taking in terms of idealised standards of rationality and overly simplified hypothetical problem scenarios (Bazerman, 2001; Kuhberger et al., 2002; McNamara & Bromiley, 1997). Rather, they suggest that the determinants of social cognition, such as historical, situational, and organisational factors, may be important in priming and contextualising risk propensity and risk-taking behaviors (Bandura & Locke, 2003; Mischel & Shoda, 1995). Self-regulation is one such factor.

Theories of Self-Regulation

In a world where organisational boundaries and networks are becoming more dynamic, distributed, and societal, social cognitive self-regulation is increasingly relevant for management studies (Brotherton, 1999; Wood, 2005). Interest in these topics has also been driven by widespread practical changes in organisational behavior, where individual initiative, teamwork, and leadership have prompted greater attention towards goal directed behavior and related self-regulatory mechanisms (Hambrick, Finkelstein, & Mooney, 2005; Kanfer, 2005). The growing interest in self-regulation also

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

340

BRYANT AND DUNFORD

reflects the fact that many psychologists have rejected narrow behaviorist and functionalist approaches to the explanation of human thought and behavior. Psychologists now explore the multidimensional nature of human consciousness and intentional agency and their expression in self-regulatory processes (Bandura, 2001; Higgins, 1998a), as well as the complex systems linking personality and self-regulation (Cervone, Shadel, Smith, & Fiori, 2006; Mischel & Shoda, 1995; Wood & Beckmann, 2006). Self-regulation thus plays an important role in social thought and behavior through influencing the nature and value of projected outcomes and the motivation systems underpinning decision-making. In exploring these features of self-regulation, scholars investigate the limits of systematic cognitive processing and the conditions under which bounded rationality is consciously deliberate or unconsciously automatic (Kahneman, 2000; Schwartz, 2002). This has led to substantial research on the perceived (as opposed to actual) outcome value in decision-making, and on the role of intuition and heuristics in such cognitive processes (Boekaerts, Pintrich, & Zeidner, 2000; Gilovich & Griffin, 2002). Yet owing to its relative novelty, the study of self-regulation still lacks broad theoretical consensus (Cervone et al., 2006). In fact, there is a range of alternative approaches to self-regulation, and contentious debates still continue (Wood, 2005). The major approaches include goal setting theory (Latham & Locke, 1991), control theory (Carver & Scheier, 1990), social cognitive theories (Bandura, 1997), and self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987), which was the precursor of regulatory focus theory (Higgins, 1998b).

Regulatory Focus Theory

Regulatory focus refers to a persons self-regulatory orientation towards future self-states. Regulatory focus is expressed as two uncorrelated constructs: promotion focus and prevention focus. Promotion focus refers to those circumstances where growth and advancement needs motivate people to try to bring themselves into alignment with their ideal selves and thus to attain desired self-states. When acting from a promotion focus, people are motivated by self-standards based on wishes and aspirations of how they would like to be. Promotion focus is therefore associated with the importance of potential gains and the use of eagerness approach means to achieve them (Higgins, 1998b). On the other hand, prevention focus refers to those circumstances where security and safety needs prompt people to seek alignment with their ought selves. From a prevention focus, people are motivated by self-standards based on felt duties and responsibilities and the avoidance of undesired self-states. Prevention focus is therefore associated with the avoidance of potential losses and the use of vigilance means to do so. In summary, a persons regulatory focus largely determines whether his or her

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

RISKY DECISION-MAKING

341

primary motivation is promotional (to advance and create), or preventative (to protect and avoid) (Higgins, Friedman, Harlow, Idson, Ayduk, & Taylor, 2001). Regulatory focus occurs as both a chronic individual variable and a situational variable (Shah, Higgins, & Friedman, 1998; Van-Dijk & Kluger, 2004). The chronic form largely derives from a persons developmental and achievement history (Higgins et al., 2001; Higgins & Silberman, 1998). Importantly, chronic regulatory focus is significantly determined by a persons accumulated experience in prior goal achievement (Higgins & Silberman, 1998), which has already been discussed as an antecedent of risk propensity (Sitkin & Pablo, 1992). At the same time, regulatory focus occurs as a situational variable, typically manipulated by problem framing that triggers signal detection mechanisms. Problems framed in terms of gains or non-gains trigger a situational promotion focus, whereas problems framed in terms of losses and non-losses trigger a situational prevention focus (Frster, Higgins, & Idson, 1998). Importantly, situational regulatory focus is significantly determined by problem framing (Idson & Liberman, 2000), which has already been identified as an antecedent of risk perception (Sitkin & Pablo, 1992). Moreover, both the chronic and situational forms of regulatory focus are uncorrelated and can therefore occur in convergent or divergent combinations (Higgins & Spiegel, 2005). When the combination is convergent, a person will possess chronic and situational promotion focus, or chronic and situational prevention focus. In contrast, when divergent, a person will possess chronic promotion focus and situational prevention focus, or chronic prevention focus and situational promotion focus. Empirical studies show that such convergent and divergent combinations of chronic and situational regulatory focus may result in different effects (Keller & Bless, 2006; Pennington & Roese, 2003; Shah et al., 1998). People with convergent chronic and situational regulatory focus experience greater motivational strength, either in eagerly approaching gains from a promotion focus or in vigilantly avoiding losses from a prevention focus. In contrast, people with divergent regulatory focus experience weaker motivational strength and more ambiguous goals (see Frster et al., 1998; Idson, Liberman, & Higgins, 2004; Keller & Bless, 2006). Patterns of convergence and divergence also influence emotional responses (Higgins, Shah, & Friedman, 1997; Idson & Liberman, 2000). Those with convergent chronic and situational promotion focus will experience stronger cheerfulness-type emotions when successful, and stronger dejection-type emotions when unsuccessful, whereas people with convergent chronic and situational prevention focus will experience stronger quiescence-type emotions when successful and stronger agitation-type emotions when unsuccessful. Divergent patterns of regulatory focus, in contrast, may result in confused and ambiguous emotional responses (Brockner & Higgins, 2001; Higgins et al., 1999; Roney, Higgins, & Shah, 1995). We next discuss how these features of regulatory focus influence risky decision-making.

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

342

BRYANT AND DUNFORD

REGULATORY FOCUS AND RISK-TAKING

Higgins and his colleagues (Higgins et al., 2001) argue that regulatory focus has important implications for decision-making and problem-solving, both as a chronic individual variable and as a situationally manipulated variable. For example, Higgins (2002) has shown that people in a promotion focus will value attainment decisions more highly than avoidance decisions; that is, they will value decisions made in the pursuit of gains more highly than decisions made in the avoidance of losses. The opposite tendencies apply for people in a prevention focus. Separately, Grant and Higgins (2003) show that promotion focus is related to being eager, risky, and oriented towards attaining gains as positive outcomes, whereas prevention focus is related to being careful, cautious, and oriented toward avoiding losses as negative outcomes. While Crowe and Higgins (1997) show that acting from a promotion focus inclines people to ensure hits and ensure against errors of omission, producing an exploratory risk-seeking bias and the use of more decision means, whereas acting from a prevention focus inclines people to ensure correct rejections and ensure against errors of commission, producing a conservative risk avoidance bias and the use of fewer decision means (Higgins, 2002). In another recent study, Kluger et al. (2004) show that under a prevention focus, feelings of probabilities closely replicate those predicted by prospect theory; while under a promotion focus, the pattern suggests a general elevation of felt probabilities, compared to those predicted by prospect theory. Importantly, regulatory focus theory introduces three sets of related distinctions that have not been incorporated into earlier models of risky decision-making. First, regulatory focus theory distinguishes between two types of orientation towards achievement success. On the one hand, when acting from a promotion focus, people are motivated to use eagerness means in pursuing attainment goals as they seek gains and try to avoid nongains. On the other hand, when acting from a prevention focus, people are motivated to use vigilance means in pursuing avoidance goals as they seek non-losses and try to avoid losses (Higgins & Spiegel, 2005). Second, regulatory focus theory recognises the situational nature of human agency by distinguishing between acts of commission versus acts of omission and their likely outcomes. In particular, when acting from a promotion focus, people are more inclined to act and thereby avoid errors of omission. Alternatively, when acting from a prevention focus, people are more inclined not to act and thereby avoid errors of commission. Third, regulatory focus stimulates different patterns of emotional responses. From a promotion focus, success stimulates cheerfulness-type emotions and failure stimulates dejection-type emotions, whereas from a prevention focus, success stimulates quiescence-type emotions and failure stimulates agitation-type emotions (Higgins et al., 1997).

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

RISKY DECISION-MAKING

343

When these distinctions are considered together, a promotion focus is positively associated with performing acts of commission in response to perceived chances of gains and avoiding errors of omission in response to perceived chances of non-gains, and success or failure in such pursuits stimulates cheerfulness or dejection-type emotions, respectively. In contrast, a prevention focus is positively associated with performing acts of omission in response to perceived chances of non-losses and avoiding errors of commission in response to perceived chances of losses, and success or failure in these pursuits stimulates quiescence or agitation-type emotions, respectively (Higgins et al., 1999). We contend that these distinctions warrant inclusion in the analysis of risky decision-making.

Regulatory Focus and Risk Propensity

Recall that chronic promotion and prevention focus are derived from a persons developmental and achievement history in attaining gains and avoiding losses, respectively (Higgins et al., 2001). This relationship to outcome history suggests a link between chronic regulatory focus and risk propensity. Studies show that a chronic promotion focus entails a propensity to take greater risks, whereas a chronic prevention focus entails greater risk aversion (Grant & Higgins, 2003). Other studies show that a persons chronic regulatory focus influences the perceived moral intensity of outcomes when committing acts of omission or commission (Camacho, Higgins, & Luger, 2003). At the same time, Sitkin and his colleagues (Sitkin & Pablo, 1992; Sitkin & Weingart, 1995) show that decision-makers seek risks related to potential gains if prior risk-seeking actions were successful, and avoid risks related to potential losses if prior risk-seeking actions were unsuccessful. It must be noted, however, that like many others, Sitkin and his colleagues assume that risk-seeking refers to potential gains rather than non-losses, and that risk avoidance refers to potential losses rather than non-gains. Notwithstanding this limitation, their findings show that a persons risktaking outcome history will significantly influence their propensity to seek or avoid similar risks in future, thereby sharing common foundations with chronic regulatory focus. We extend these findings by distinguishing between a history of risktaking achievement in attaining gains and avoiding non-gains (reinforcing chronic promotion focus), and a history of risk-taking achievement in avoiding losses and attaining non-losses (reinforcing chronic prevention focus). First, when acting from a chronic promotion focus, people tend to approach new tasks as opportunities to attain gains. They are oriented towards new task goals with eagerness approach means and seek to achieve positive outcomes (Higgins et al., 2001). This in turn suggests that acting from chronic promotion focus will incline people to exhibit a risk-seeking

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

344

BRYANT AND DUNFORD

propensity in relation to commission risk (seeking gains that could result from acting), and a risk-avoidance propensity in relation to omission risk (avoiding non-gains that could result from failing to act) (cf. Crowe & Higgins, 1997). Moreover, studies suggest that the stronger the chronic promotion focus, the stronger the risk propensity in these respects (Higgins et al., 1999). We therefore contend that chronic promotion focus influences the effect of outcome history on risk propensity by inclining people to seek commission risks (defined as the chance of outcomes resulting from acting) and avoid omission risks (defined as the chance of outcomes resulting from not acting). We further contend that chronic promotion focus inclines people towards stronger commission risk-seeking propensity, in comparison to omission risk-avoiding propensity (cf. Frster et al., 1998; Idson et al., 2004).

Proposition 1a: Chronic promotion focus is positively related to the propensity to seek commission risks because they could result in gains. Proposition 1b: Chronic promotion focus is positively related to the propensity to avoid omission risks because they could result in non-gains. Proposition 1c: When acting from chronic promotion focus, the propensity to seek commission risks is stronger than the propensity to avoid omission risks.

On the other hand, when people act from prevention focus, they tend to perceive new tasks in terms of avoiding potential losses. In other words, people who act from prevention focus are oriented towards new tasks with vigilance means and the goal of avoiding negative outcomes (Higgins et al., 2001). This in turn suggests that people acting from chronic prevention focus will tend to exhibit a risk-seeking propensity in relation to omission risks that could result in non-losses, and a risk-avoidance propensity in relation to commission risks that could result in losses. Thus, we contend that chronic prevention focus influences the effect of outcome history on risk propensity by inclining people to seek omission risks and avoid commission risks. We also contend that chronic prevention focus inclines people towards stronger commission risk-avoiding propensity, in comparison to omission risk-seeking propensity.

Proposition 2a: Chronic prevention focus is positively related to the propensity to seek omission risks because they could result in non-losses. Proposition 2b: Chronic prevention focus is positively related to the propensity to avoid commission risks because they could result in losses. Proposition 2c: When acting from chronic prevention focus, the propensity to avoid commission risks is stronger than the propensity to seek omission risks.

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

RISKY DECISION-MAKING

345

Notably, this paper is among the first to make explicit claims regarding the relationship between outcome history, regulatory focus, and risk propensity (cf. Higgins, 2002; Kluger et al., 2004). Yet these links are implicitly drawn by Sitkin and Pablo (1992) when they argue that if decision-makers can link outcomes to their actions, those who have been successful by being risk-averse will become increasingly risk-averse, and those who have been successful by being risk-seeking will become increasingly risk-seeking. As noted earlier, similar processes underpin the development of chronic regulatory focus, whereby a developmental history of positive attainment and reinforcement leads to chronic promotion focus, and a history of preventative achievement and reinforcement leads to chronic prevention focus (Higgins et al., 2001; Higgins & Silberman, 1998). These findings also suggest a deeper role for regulatory focus in risk perception, as we explain in the next section.

Regulatory Focus and Risk Perception

Framing situations in terms of gains and non-gains triggers a situational promotion focus, thus inclining people to approach task situations using eagerness means to attain gains (Crowe & Higgins, 1997; Higgins, 2002). People then employ more goal pursuit means and have a heightened awareness of positive commission risk defined as the positive consequences of acting (achieving gains), as well as a heightened awareness of negative omission risk defined as the negative consequences of failing to act (achieving non-gains), whereas framing situations in terms of losses and non-losses triggers a situational prevention focus, thus inclining people to approach situations using vigilance means to avoid losses. People then employ fewer goal pursuit means and have a heightened awareness of positive omission risk defined as the positive consequences of not acting (achieving non-losses), as well as a heightened awareness of negative commission risk defined as the negative consequences of acting (achieving losses) (Higgins, 2002). These distinctions are directly relevant to problem framing as an antecedent of risk perception. That is, framing problems in terms of gains or losses triggers situational regulatory focus which in turn influences the perception of risk (Keller & Bless, 2006; Shah et al., 1998). First, when acting from situational promotion focus, people are more inclined to perceive the chance of gains as positive risk and the chance of non-gains as negative risk. Alternatively, acting from a situational prevention focus inclines people to perceive the chance of non-losses as positive risk and the chance of losses as negative risk (cf. Williams & Voon, 1999; Williams, Zainuba, & Jackson, 2003). It follows that in some circumstances the same potential outcome can be perceived as a negative risk of non-gains from a promotion focus, yet perceived as a positive risk of non-losses from a prevention focus (see Idson

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

346

BRYANT AND DUNFORD

& Liberman, 2000). Thus, framing risks in terms of gains and non-gains, or in terms of losses and non-losses, triggers situational promotion and prevention focus, respectively, which in turn influence whether such risks are perceived as positive or negative. To date, however, these distinctions have been largely ignored in studies of risky decision-making. Scholars typically draw distinctions in terms of outcome valence and ignore signal detection mechanisms. Consequently, they assume that positive risk refers to the chance of achieving gains and negative risk refers to the chance of incurring losses (e.g. Kahneman & Tversky, 2000b; McNamara & Bromiley, 1999; Simon & Houghton, 2003). In contrast, we argue that depending on a persons situational regulatory focus, the chance of non-losses can also be perceived as positive risk from a prevention focus, and the chance of non-gains can be perceived as negative risk from a promotion focus (Liberman et al., 2005). These distinctions can also be stated in relation to acts of commission and omission. From a situational promotion focus, people tend to perceive acts of omission as negative risks because such acts could lead to non-gains, and they tend to perceive acts of commission as positive risks because they could lead to gains. Moreover, they tend to perceive positive commission risk more intensely than negative omission risk because they regard attaining gains as more important than avoiding non-gains (see Idson & Higgins, 2000). These tendencies are further amplified because acting from promotion focus inclines people to more eager pursuit of gains and the use of more decision means. Therefore, any single act of commission in risky decision-making is viewed as less critical compared to multiple decision means.

Proposition 3a: When acting from situational promotion focus, omission risks are perceived as negative risks because they could result in non-gains. Proposition 3b: When acting from situational promotion focus, commission risks are perceived as positive risks because they could result in gains. Proposition 3c: When acting from situational promotion focus, the perception of positive commission risks is more intense than the perception of negative omission risks.

On the other hand, a person acting from situational prevention focus will tend to approach new tasks with a desire to avoid losses. This in turn will lead to alternative perceptions of omission risk and commission risk. Such people will tend to perceive acts of omission as positive risks because they could lead to non-losses. On the other hand, they will tend to perceive acts of commission as negative risks because they could lead to losses. Moreover, they will perceive negative commission risk more intensely than positive omission risk. This tendency is amplified because acting from prevention

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

RISKY DECISION-MAKING

347

focus leads people to use fewer decision means in order to avoid losses. Thus, any single act of commission in risky decision-making is viewed as more critical compared to fewer decision means. We therefore contend that situational prevention focus influences risk perception.

Proposition 4a: When acting from a situational prevention focus, omission risks are perceived as positive risks because they could result in non-losses. Proposition 4b: When acting from a situational prevention focus, commission risks are perceived as negative risks because they could result in losses. Proposition 4c: When acting from a situational prevention focus, the perception of negative commission risks is more intense than the perception of positive omission risks.

Regulatory Focus and Emotion in Risky Decision-Making

Regulatory focus also stimulates emotional responses. In fact, Higgins and his colleagues (Higgins et al., 1999, p. 256) argue that the direct experience of the particular self-regulatory process working or not working is the emotion. In support of this contention, studies show that people acting from chronic or situational promotion focus will experience cheerfulness-type emotions when successful and dejection-type emotions when unsuccessful, and will experience more intense emotions in relation to potential gains as opposed to non-gains. In contrast, people acting from either chronic or situational prevention focus will experience quiescence-type emotions when successful and agitation-type emotions when unsuccessful, and will experience more intense emotions in relation to potential losses as opposed to non-losses. The intensity of these emotional responses also depends on the convergence of chronic and situational regulatory focus (Idson et al., 2004; Keller & Bless, 2006). For example, when acting from both chronic and situational promotion focus, cheerfulnessdejection emotional responses will be relatively strong and unambiguous. However, it is important to recall that chronic and situational regulatory focus are uncorrelated and may occur in divergent combinations (Higgins & Spiegel, 2005). It is therefore possible for people to experience mixed patterns of emotion in relation to risky decision-making tasks. For example, a person may possess chronic promotion focus in combination with situational prevention focus. Such a person will then experience a mixture of cheerfulnessdejection emotions from chronic promotion focus as well as quiescenceagitation emotions from a situational prevention focus. Insofar as these complex emotional responses reflect the degree to which regulatory focus is working or not working, they will impact on the felt intensity of a persons

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

348

BRYANT AND DUNFORD

risk perception and risk propensity (cf. Higgins et al., 1999). We contend that these effects underpin emotional responses in risky decision-making. First, when acting from a chronic promotion focus, people have a propensity towards seeking commission risk and avoiding omission risk. Following the reasoning of Higgins and his colleagues (Higgins et al., 1999), chronic promotion focus is said to be working in these situations, rather than not working. It follows that when people act from chronic promotion focus and seek commission risk or avoid omission risk, they will experience cheerfulness-type emotions. Furthermore, they will experience such emotions more intensely when seeking commission risk in comparison to avoiding omission risk. In contrast, when people act from chronic promotion focus and do not seek commission risk or do not avoid omission risk, they will experience dejection-type emotions. These emotions will be more intense when not seeking commission risk in comparison to not avoiding omission risk (Frster et al., 1998; Shah, Brazy, & Higgins, 2004).

Proposition 5a: When acting from a chronic promotion focus, cheerfulness-type emotions are more intense when seeking commission risk than avoiding omission risk. Proposition 5b: When acting from a chronic promotion focus, dejection-type emotions are more intense when not seeking commission risk than not avoiding omission risk.

Second, when acting from a chronic prevention focus, people have a propensity towards seeking omission risk and avoiding commission risk. Once again, chronic regulatory focus is said to be working in these situations, rather than not working (Higgins et al., 1999). It follows that when people act from chronic prevention focus and seek omission risk or avoid commission risk, they will experience quiescence-type emotions, and experience such emotions more intensely when avoiding commission risk in comparison to seeking omission risk. In contrast, when people act from chronic prevention focus and do not seek omission risk or do not avoid commission risk, they will experience agitation-type emotions, and experience such emotions more intensely when not avoiding commission risk in comparison to not seeking omission risk.

Proposition 6a: When acting from a chronic prevention focus, quiescencetype emotions are more intense when avoiding commission risk than seeking omission risk. Proposition 6b: When acting from a chronic prevention focus, agitation-type emotions are more intense when not avoiding commission risk than not seeking omission risk.

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

RISKY DECISION-MAKING

349

Comparable effects occur in relation to risk perception. When acting from a situational promotion focus, we argue that people are inclined to perceive commission risk as positive and omission risk as negative. Situational promotion focus is said to be working in these situations, rather than not working, and they will experience cheerfulness-type emotions (Higgins et al., 1999). In contrast, when people act from situational promotion focus and do not perceive commission risk as positive, or do not perceive omission risk as negative, they will experience dejection-type emotions. Such incongruence could be owing to framing effects or other personal and situational conditions (Frster et al., 1998; Idson & Liberman, 2000).

Proposition 7a: When acting from a situational promotion focus, cheerfulnesstype emotions are more intense when perceiving positive commission risk than perceiving negative omission risk. Proposition 7b: When acting from a situational promotion focus, dejectiontype emotions are more intense when not perceiving positive commission risk than not perceiving negative omission risk.

On the other hand, when acting from a situational prevention focus, we argue that people are inclined towards perceiving omission risk as positive and commission risk as negative. Situational promotion focus is said to be working in these situations, rather than not working, thus stimulating quiescence-type emotions (Higgins et al., 1999). In contrast, when people act from a situational prevention focus and do not perceive omission risk as positive or do not perceive commission risk as negative, they will experience agitation-type emotions, and experience such negative emotions more intensely when not perceiving negative commission risk.

Proposition 8a: When acting from a situational prevention focus, quiescencetype emotions are more intense when perceiving negative commission risk than perceiving positive omission risk. Proposition 8b: When acting from a situational prevention focus, agitationtype emotions are more intense when not perceiving negative commission risk than not perceiving positive omission risk.

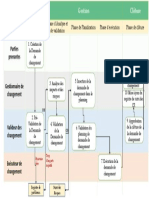

A New Model of Risky Decision-Making

In summary, the arguments and propositions stated above suggest that regulatory focus is an important factor in risky decision-making. First, we argue that chronic regulatory focus influences risk propensity by creating tendencies towards seeking or avoiding omission risk and commission risk. Second, we argue that situational regulatory focus influences risk perception

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

350

BRYANT AND DUNFORD

by creating tendencies towards perceiving omission risk and commission risk as positive or negative risk. Third, we argue that regulatory focus underpins complex emotional responses in risky decision-making, depending on whether regulatory focus is working or not working in relation to risk propensity and/or risk perception. The fundamental distinction drawn in each set of propositions is between alternative approaches to acts of omission and commission, and the different patterns of risk perception, risk propensity, and associated emotional responses. These proposed relationships are combined in a new model of risky decision-making in Figure 1. The figure depicts outcome history as an antecedent of both chronic regulatory focus and risk propensity, and depicts problem framing as an antecedent of both situational regulatory focus and risk perception. Figure 1 also shows the influence of chronic and situational regulatory focus with respect to risk propensity, risk perception, and emotional responses in risky decisionmaking. The propositions we have developed therefore suggest that risky decisionmaking cannot be understood in terms of gains and losses simply defined, but must take into account the risk-takers regulatory orientation. When viewed from this perspective, a specific act of commission may be perceived as a positive risk of gain from a promotion focus, yet perceived as a negative risk of loss from a prevention focus. Contrariwise, a specific act of omission may be perceived as a positive risk of non-loss from a prevention focus, yet perceived as a negative risk of loss from a prevention focus. In previous studies, these distinctions are rarely drawn (see Kluger et al., 2004). Moreover, both scenarios can apply to exactly the same problem situation, and may only differ in terms of the framing conditions and actors regulatory orientations. Consequently, we contend that the analysis of

FIGURE 1.

Model of risky decision-making.

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

RISKY DECISION-MAKING

351

risk-taking must incorporate these distinctions and the historical and situational factors that influence agents inclinations to commit or omit action. The proposed model in Figure 1 does so.

DISCUSSION

Our propositions and model have a number of important implications for future theory development and empirical research. First, building on the pioneering work of Kahneman and Tversky (1979), many scholars investigate the role of problem framing in risky decision-making. As noted earlier, this research typically assumes that positive risk framing refers to chances of gains and negative risk framing refers to chances of losses. In contrast, we argue that positive risk can refer to either chances of gains from a promotion focus, or chances of non-losses from a prevention focus; while negative risk can refer to either chances of non-gains from a promotion focus, or chances of losses from a prevention focus (Idson & Liberman, 2000). This implies that a specific outcome prospect could be perceived as either a negative or positive risk, depending on the regulatory focus of the perceiver. More specifically, an act of omission can be perceived as a positive risk from a prevention focus (chance of non-loss), or perceived as a negative risk from a promotion focus (chance of non-gain). Alternatively, an act of commission can be perceived as a positive risk from a promotion focus (chance of gain), or perceived as a negative risk from a prevention focus (chance of loss). Previous research conflates these fundamental distinctions between acting and not acting, thereby failing to uncover important factors in risky decision-making and their implications for the analysis of agentic behavior (see Bandura, 2006; Mischel, 2004). Importantly, our model also suggests that commission risk stimulates more intense cognitive and emotional responses, in comparison to omission risk. On the one hand, from a promotion focus, commission risk stimulates more intense risk-seeking propensity, positive risk perception, and cheerfulnesstype emotions, as people use stronger eagerness approach means with respect to potential gains. On the other hand, from a prevention focus, commission risk stimulates more intense risk-avoidance propensity, negative risk perception, and agitation-type emotions, as people use stronger vigilance avoidance means with respect to potential losses (see Frster, Grant, Idson, & Higgins, 2001; Idson & Higgins, 2000). By comparison, omission risk stimulates less intense risk-avoiding propensity, negative risk perception, and dejection-type emotions from a promotion focus as people seek to avoid nongains, while omission risk stimulates less intense risk-seeking propensity, positive risk perception, and quiescence-type emotions from a prevention focus as people seek to attain non-losses. In summary, the risks of commission loom larger than the risks of omission and stimulate more intense responses.

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

352

BRYANT AND DUNFORD

Other conflations abound in the literature with respect to the emotional responses and felt intensities of risky decision-making. Following Kahneman and Tversky (1979) once again, scholars typically associate positive emotions with potential gains and negative emotions with potential losses (Liberman et al., 2005). However, this analysis conflates the different emotional responses associated with regulatory focus working or not working (Higgins et al., 1999). In contrast, our model suggests that positive and negative emotions occur in relation to both promotion and prevention orientations in risky decision-making, and that these emotional responses vary in both nature and intensity depending on the relative strength and degree of convergence between chronic and situational regulatory focus. For example, our model suggests that negative dejection-type emotions are associated with not seeking commission risk from a promotion focus, while negative agitation-type emotions are associated with not avoiding commission risk from a prevention focus. That is, depending on a persons regulatory focus, they will experience very different negative emotions in relation to regulatory focus not working in relation to perceived commission risk. Apart from recent work by Higgins and others (Higgins, 2002; Idson & Liberman, 2000; Kluger et al., 2004), such fundamental distinctions are not made in previous treatments of risky decision-making. As a related contribution, our model throws new light on the important distinction derived from Tversky and Kahnemans (e.g. 1986, 1991) prospect theory, that losses are felt more intensely than foregone gains. Our model provides a possible explanation for this effect. Building on the analysis offered by Higgins and his colleagues (Higgins, 2002; Liberman et al., 2005), the model suggests that acting from prevention focus results in more intense negative agitation-type emotions when a person fails to avoid negative commission risk (thus incurring losses); whereas, acting from promotion focus results in less intense negative dejection-type emotions when a person fails to avoid negative omission risk (thus foregoing gains). This constitutes a novel contribution to the explanation of these observed effects. Given the importance of these phenomena within the study of risky decision-making, we encourage researchers to explore these proposed relationships further. Additional implications flow from our model with respect to the interaction of emotion and heuristic bias in risky decision-making. The model suggests that when acting from promotion focus, a persons actual and anticipatory emotional response may strengthen biases that inflate the chances of gains from acts of commission and deflate the chances of non-gains from acts of omission. Alternatively, our model suggests that when acting from prevention focus, a persons actual and anticipatory emotional response may strengthen biases that inflate the chances of losses from acts of commission and deflate the chances of non-losses from acts of omission. Moreover, previous studies

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

RISKY DECISION-MAKING

353

suggest that these effects would be enhanced because regulatory focus is thus concurrent with heuristic biases as goal pursuit means (Idson et al., 2004). If these arguments are correct, then regulatory focus underpins fundamental patterns of cognitiveaffective interaction that have been ignored in most prior studies of heuristic bias in risky decision-making. We therefore welcome studies that start to address these aspects of risk-taking (e.g. Bryant, 2007; Higgins, 2000a; Kluger et al., 2004). Related implications flow for strategic decision-making. Studies show that positive emotion inclines decision-makers to frame situational risks more positively, yet leads to risk-avoidance owing to the desire to maintain a positive emotional state (Mittal & Ross, 1998; Williams et al., 2003). A reverse pattern occurs in relation to negative emotion, which encourages negative risk framing and greater risk-taking owing to the desire to improve ones emotional state. However, these studies conflate the important distinction between cheerfulnessdejection-type emotions and quiescence agitation-type emotions under promotion or prevention focus, respectively. That is, depending on the decision-makers dominant regulatory orientation, he or she will experience different positive and negative emotions in strategic decision-making. For example, if an executive acts from prevention focus, he or she would be inclined to experience positive quiescencetype emotions when seeking risks of omission; yet an executive acting from promotion focus would be inclined to experience negative dejection-type emotions when not avoiding the equivalent risks of omission. Therefore, an omission risk can be associated with either a positive or negative emotional response, depending on the decision-makers regulatory orientation. These complex relations warrant attention in future research into the role of emotion in strategic decision-making and the influence of emotional climate on these processes (see Brockner & Higgins, 2001; Wallace & Gilad, 2006). In summary, our model suggests that complex psychosocial, historical, and situational factors require greater attention in future research, because these factors are among the antecedents of regulatory focus. However, risky decision-making has often been studied experimentally using contrived scenarios that are devoid of situational and historical context (Bazerman, 2001; Williams et al., 2003). In contrast, we argue that the study of risky decision-making requires close attention to these factors. Therefore we encourage researchers to incorporate these elements into future research design. This is especially important for research into specific task domains such as organisational and management decision-making, where contextual factors appear to play a major role in risk-taking (March & Shapira, 1987; Sitkin & Pablo, 1992) and situational regulatory focus (Brockner & Higgins, 2001). Future practice may also benefit from the proposed model, for it opens up the possibility of new ways to manage risk-taking within organisational

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

354

BRYANT AND DUNFORD

and social settings. Instead of assuming that risk perception and risk propensity are more or less stable and fixed, organisations and individuals could adopt social cognitive strategies that may alter risk-taking behaviors through reinforcing and/or priming regulatory focus. For example, by making appropriate interventions that influence situational regulatory focus, people may be led to frame risks as more or less positive or negative in particular problem situations (Higgins & Spiegel, 2005). Other techniques could be employed to encourage or discourage access to chronic regulatory focus, thereby influencing a persons risk propensity. If such techniques can be developed, they would provide new management tools in situations where people needed to be more concerned with either avoiding losses from a prevention focus, such as insurance and credit risk, or attaining gains from a promotion focus, such as sales and marketing campaigns.

Conclusion

We took as a starting point our agreement with the behavioral critique of the classical Bayesian assumptions that still frame much of the debate about risk-taking (see Gigerenzer, 1996; Kahneman & Tversky, 1996). These assumptions include the belief that complete information is potentially available, that rationality is ideally unbounded and objective, and that human decision-making is primarily aimed at utility maximisation. This classical perspective also assumes that all problem situations share the same fundamental risk characteristics. In the past, those assumptions led to a distorted view of the risk-taking process (Schwartz, 2002) and skewed the analysis of risk-taking by neglecting psychosocial factors and situational variables. They also failed to recognise that people have different risk responses and outcome preferences reflecting psychosocial factors that include self-regulatory orientation. In response to these limitations of classically inspired theories of risk, numerous scholars have developed models that seek to incorporate the situational and psychosocial factors that influence risky decisions. As a result, we now have a far deeper understanding of the role played by cognitive biases, affective states, achievement outcome history, dispositional preferences, and situational factors. However, there is still much work to do and significant gaps remain. In seeking to advance understanding of these processes, this paper investigates the role of regulatory focus in risky decision-making. It argues that regulatory focus plays a complex role in risky decisionmaking. In particular, the paper argues that chronic regulatory focus influences risk propensity, and that situational regulatory focus influences risk perception. In addition, the paper argues that regulatory focus working or not working in relation to risk propensity and risk perception stimulates complex emotional responses. Our resulting model of risky decision-making

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

RISKY DECISION-MAKING

355

summarises these arguments and the propositions derived from them. Numerous implications follow for those fields concerned with the analysis and management of risk. We encourage future researchers to expand and test the model and propositions derived in this paper.

REFERENCES

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 126. Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(2), 164 180. Bandura, A., & Locke, E.A. (2003). Negative self-efficacy and goal effects revisited. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 8799. Baron, R.M., & Kenny, D.A. (1986). The moderatormediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 11731182. Bazerman, M.H. (2001). The study of real decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 14(5), 353 384. Beach, L.R., & Connolly, T. (2005). The psychology of decision making: People in organizations (2nd edn.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Boekaerts, M., Maes, S., & Karoly, P. (2005). Self-regulation across domains of applied psychology: Is there an emerging consensus? Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54(2), 149 154. Boekaerts, M., Pintrich, P.R., & Zeidner, M. (2000). Self-regulation: An introductory overview. In M. Boekaerts, P.R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of selfregulation (pp. 19). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Brockner, J., & Higgins, E.T. (2001). Regulatory focus theory: Implications for the study of emotions at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(1), 35 66. Brotherton, C. (1999). Social psychology and management. Buckingham: Open University Press. Bryant, P. (2007). Self-regulation and decision heuristics in entrepreneurial opportunity evaluation and exploitation. Management Decision, 45(4), 732748. Camacho, C.J., Higgins, E.T., & Luger, L. (2003). Moral value transfer from regulatory fit: What feels right is right and what feels wrong is wrong. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 498 508. Camerer, C.F., & Loewenstein, G. (2004). Behavioral economics: Past, present, future. In C.F. Camerer, G. Loewenstein, & M. Rabin (Eds.), Advances in behavioral economics (pp. 351). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Carver, C.S., & Scheier, M.F. (1990). Origins and functions of positive and negative affect: A control-process view. Psychological Review, 97(1), 1935. Cervone, D., Shadel, W.G., Smith, R.E., & Fiori, M. (2006). Self-regulation: Reminders and suggestions from personality science. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 55(3), 333 385.

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

356

BRYANT AND DUNFORD

Crowe, E.B., & Higgins, E.T. (1997). Regulatory focus and strategic inclinations: Promotion and prevention in decision-making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 69(2), 117132. Das, T.K., & Teng, B.-S. (2004). The risk-based view of trust: A conceptual framework. Journal of Business and Psychology, 19(1), 85116. Frster, J., Grant, H., Idson, L.C., & Higgins, E.T. (2001). Success/failure feedback, expectancies, and approach/avoidance motivation: How regulatory focus moderates classic relations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37(3), 253260. Frster, J., Higgins, E.T., & Bianco, A.T. (2003). Speed/accuracy decisions in task performance: Built-in trade-off or separate strategic concerns? Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 90(1), 148164. Frster, J., Higgins, E.T., & Idson, L.C. (1998). Approach and avoidance strength during goal attainment: Regulatory focus and the goal looms larger effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(5), 11151131. Geiger, S.W., Robertson, C.J., & Irwin, J.G. (1998). The impact of cultural values on escalation of commitment. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 6(2), 165 176. Gigerenzer, G. (1996). On narrow norms and vague heuristics: A reply to Kahneman and Tversky (1996). Psychological Review, 103(3), 592596. Gilovich, T., & Griffin, D. (2002). Introductionheuristics and biases: Then and now. In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment (pp. 118). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Grant, H., & Higgins, E.T. (2003). Optimism, promotion pride, and prevention pride as predictors of quality of life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(12), 15211532. Hambrick, D.C., Finkelstein, S., & Mooney, A.C. (2005). Executive job demands: New insights for explaining strategic decisions and leader behaviors. Academy of Management Review, 30(3), 472 491. Higgins, E.T. (1987). Self discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319340. Higgins, E.T. (1998a). From expectancies to worldviews: Regulatory focus in socialization and cognition. In J.M. Darley & J. Cooper (Eds.), Attribution and social interaction: The legacy of Edward E. Jones (pp. 243269). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Higgins, E.T. (1998b). Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 146. Higgins, E.T. (2000a). Making a good decision: Value from fit. American Psychologist, 55(11), 12171230. Higgins, E.T. (2000b). Social cognition: Learning about what matters in the social world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30, 339. Higgins, E.T. (2002). How self-regulation creates distinct values: The case of promotion and prevention decision making. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 12(3), 177191. Higgins, E.T., Friedman, R.S., Harlow, R.E., Idson, L.C., Ayduk, O.N., & Taylor, A. (2001). Achievement orientations from subjective histories of success: Promotion pride versus prevention pride. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31(1), 3 23. Higgins, E.T., Grant, H., & Shah, J. (1999). Self-regulation and quality of life: Emotional and non-emotional life experiences. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, &

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

RISKY DECISION-MAKING

357

N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 244 266). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Higgins, E.T., Shah, J., & Friedman, R. (1997). Emotional responses to goal attainment: Strength of regulatory focus as moderator. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(3), 515 525. Higgins, E.T., & Silberman, I. (1998). Development of regulatory focus: Promotion and prevention as ways of living. In J. Heckhausen & C.S. Dweck (Eds.), Motivation and self-regulation across the life span (pp. 78113). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Higgins, E.T., & Spiegel, S. (2005). Promotion and prevention strategies for selfregulation: A motivated cognition perspective. Columbia Business School Working Paper (pp. 133). New York: Columbia Business School. Idson, L.C., & Higgins, E.T. (2000). How current feedback and chronic effectiveness influence motivation: Everything to gain versus everything to lose. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30(4), 583 592. Idson, L.C., & Liberman, N. (2000). Distinguishing gains from nonlosses and losses from nongains: A regulatory focus perspective on hedonic intensity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 36(3), 252274. Idson, L.C., Liberman, N., & Higgins, E.T. (2004). Imagining how youd feel: The role of motivational experiences from regulatory fit. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(7), 926 937. Kahneman, D. (2000). New challenges to the rationality assumption. In D. Kahneman & A. Tversky (Eds.), Choices, values, and frames (pp. 758 774). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263 292. Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1996). On the reality of cognitive illusions. Psychological Review, 103(3), 582591. Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2000a). Choices, values, and frames. In D. Kahneman & A. Tversky (Eds.), Choices, values, and frames (pp. 116). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2000b). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In D. Kahneman & A. Tversky (Eds.), Choices, values, and frames (pp. 1743). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kanfer, R. (2005). Self-regulation research in work and I/O psychology. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54(2), 186 191. Keller, J., & Bless, H. (2006). Regulatory fit and cognitive performance: The interactive effect of chronic and situationally induced self-regulatory mechanisms on test performance. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36(3), 393 405. Kluger, A.N., Stephan, E., Ganzach, Y., & Hershkovitz, M. (2004). The effect of regulatory focus on the shape of probability-weighting function: Evidence from a cross-modality matching method. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 95(1), 20 39. Krueger Jr., N.F., & Dickson, P.R. (1994). How believing in ourselves increases risk taking: Perceived self-efficacy and opportunity recognition. Decision Sciences, 25(3), 385 400.

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

358

BRYANT AND DUNFORD

Kuhberger, A., Schulte-Mecklenbeck, M., & Perner, J. (2002). Framing decisions: Hypothetical and real. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89(2), 11621175. Latham, G.P., & Locke, E.A. (1991). Self-regulation through goal setting. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 212247. Liberman, N., Idson, L.C., & Higgins, E.T. (2005). Predicting the intensity of losses vs. non-gains and non-losses vs. gains in judging fairness and value: A test of the loss aversion explanation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(5), 527 534. McNamara, G., & Bromiley, P. (1997). Decision making in an organizational setting: Cognitive and organizational influences on risk assessment in commercial lending. Academy of Management Journal, 40(5), 10631088. McNamara, G., & Bromiley, P. (1999). Risk and return in organizational decision making. Academy of Management Journal, 42(3), 330340. March, J.G. (1997). Understanding how decisions happen in organisations. In Z. Shapira (Ed.), Organizational decision making (pp. 932). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. March, J.G., & Shapira, Z. (1987). Managerial perspectives on risk and risk taking. Management Science, 33(11), 1404 1418. Mischel, W. (2004). Toward an integrative science of the person. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 122. Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1995). A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review, 102(2), 246 268. Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1998). Reconciling processing dynamics and personality dispositions. Annual Review of Psychology, 49(1), 229258. Mittal, V., & Ross, W.T.J. (1998). The impact of positive and negative affect and issue framing on issue interpretation and risk taking. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 76(3), 298 324. Molden, D.C., & Higgins, E.T. (2004). Categorization under uncertainty: Resolving vagueness and ambiguity with eager versus vigilant strategies. Social Cognition, 22(2), 248277. Pablo, A.L., Sitkin, S.B., & Jemison, D.B. (1996). Acquisition decision-making processes: The central role of risk. Journal of Management, 22(5), 723746. Pennington, G.L., & Roese, N.J. (2003). Regulatory focus and temporal distance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39(6), 563576. Roney, C.J.R., Higgins, E.T., & Shah, J. (1995). Goals and framing: How outcome focus influences motivation and emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(11), 11511160. Schwartz, H. (2002). Herbert Simon and behavioral economics. Journal of SocioEconomics, 31, 181189. Shah, J.Y., Brazy, P.C., & Higgins, E.T. (2004). Promoting us or preventing them: Regulatory focus and manifestations of intergroup bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(4), 433 445. Shah, J.Y., Higgins, E.T., & Friedman, R.S. (1998). Performance incentives and means: How regulatory focus influences goal attainment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 285 293.

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

RISKY DECISION-MAKING

359

Simon, H.A. (1979). Rational decision making in business organizations. American Economic Review, 69(4), 493 513. Simon, M., & Houghton, S.M. (2003). The relationship between overconfidence and the introduction of risky products: Evidence from a field study. Academy of Management Journal, 46(2), 139149. Sitkin, S.B., & Pablo, A.L. (1992). Reconceptualizing the determinants of risk behavior. Academy of Management Review, 17(1), 938. Sitkin, S.B., & Weingart, L.R. (1995). Determinants of risky decision-making behavior: A test of the mediating role of risk perceptions and propensity. Academy of Management Journal, 38(6), 1573 1592. Slovic, P. (2000a). Introduction and overview. In P. Slovic (Ed.), The perception of risk (pp. xxixxxvi). London and Sterling, VA: Earthscan. Slovic, P. (2000b). Trust, emotion, sex, politics and science: Surveying the riskassessment battlefield. In P. Slovic (Ed.), The perception of risk (pp. 390412). London and Sterling, VA: Earthscan. Thaler, R.H. (2000). From homo economicus to homo sapiens. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(1), 133 141. Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1986). Rational choice and the framing of decisions. Journal of Business, 59(4), 251278. Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1991). Loss aversion in riskless choice: A referencedependent model. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 10391061. Van-Dijk, D., & Kluger, A.N. (2004). Feedback sign effect on motivation: Is it moderated by regulatory focus? Applied Psychology: An International Review, 53(1), 113 135. Wallace, C., & Gilad, C. (2006). A multilevel integration of personality, climate, selfregulation, and performance. Personnel Psychology, 59(3), 529557. Williams, S., & Voon, Y.W.W. (1999). The effects of mood on managerial risk perceptions: Exploring affect and the dimensions of risk. Journal of Social Psychology, 139(3), 268 287. Williams, S., Zainuba, M., & Jackson, R. (2003). Affective influences on risk perceptions and risk intention. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(1/2), 126137. Wong, K.F.E. (2005). The role of risk in making decisions under escalation situations. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54(4), 584607. Wood, R.E. (2005). New frontiers for self-regulation research in IO psychology. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54(2), 192198. Wood, R.E., & Beckmann, N. (2006). Personality architecture and the FFM in organisational psychology. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 55(3), 453 469.

2008 The Authors. Journal compilation 2008 International Association of Applied Psychology.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Cours 21-26 (Unite 6 +7)Document54 pagesCours 21-26 (Unite 6 +7)Maria SimotaPas encore d'évaluation

- Les Biomarqueurs de L'infarctus Du Myocarde: ChapitreDocument8 pagesLes Biomarqueurs de L'infarctus Du Myocarde: ChapitreTarek SayhiPas encore d'évaluation

- B 800 Cbe 59Document2 pagesB 800 Cbe 59mahdi elmayPas encore d'évaluation

- TD BetonDocument10 pagesTD BetonAggoun YounesPas encore d'évaluation

- Vedette Matiére RAMEAU CORRIGEDocument5 pagesVedette Matiére RAMEAU CORRIGEBob Cavallo HBPas encore d'évaluation

- CND SRDocument2 pagesCND SRFethi BELOUISPas encore d'évaluation

- Calcul Des Roulements 2Document11 pagesCalcul Des Roulements 2Amine MechPas encore d'évaluation

- Programme AidesoignantfinalDocument63 pagesProgramme AidesoignantfinalAbdelghni LachhabPas encore d'évaluation

- 25 - Workflow Demande de ModificationDocument1 page25 - Workflow Demande de ModificationSerge VolpiPas encore d'évaluation

- Abord Premier de L'artère Mésentérique Supérieure Au Cours de La Duodénopancréatectomie CéphaliqueDocument3 pagesAbord Premier de L'artère Mésentérique Supérieure Au Cours de La Duodénopancréatectomie CéphaliquefdroooPas encore d'évaluation

- Ecoconso - Que Signifient Les Nouveaux Pictogrammes de Danger - 2023-02-01Document4 pagesEcoconso - Que Signifient Les Nouveaux Pictogrammes de Danger - 2023-02-01Dieudonné NofodjiPas encore d'évaluation

- FIT Manioc 2014Document2 pagesFIT Manioc 2014Williams Koffi100% (1)

- Mesures Anthropométriques Pour L'évaluation de L'état Nutritionnel D'un Individu & La Situation Dans Une CommunautéDocument67 pagesMesures Anthropométriques Pour L'évaluation de L'état Nutritionnel D'un Individu & La Situation Dans Une CommunautéIbrahim HamadouPas encore d'évaluation

- TP Mineralogie PDFDocument40 pagesTP Mineralogie PDFMohamed Al100% (3)

- TD ExternesDocument24 pagesTD ExternesDoria OuahraniPas encore d'évaluation

- Coloration GramDocument6 pagesColoration GramFatmazohra RAHILPas encore d'évaluation

- SN5 Corrige3 VFDocument23 pagesSN5 Corrige3 VFSimrat KaurPas encore d'évaluation

- Brochure Charte Audit Interne 2015def22x23def16pages Corrig2e 1Document16 pagesBrochure Charte Audit Interne 2015def22x23def16pages Corrig2e 1ʚïɞ Fi Fi ʚïɞPas encore d'évaluation

- Cours Equipements StatiquesDocument107 pagesCours Equipements Statiquesرضا بن عمارPas encore d'évaluation

- 14 Antalgiques PDFDocument50 pages14 Antalgiques PDFLonely SnailPas encore d'évaluation

- Graniscel S55Document2 pagesGraniscel S55Aîda hajriPas encore d'évaluation

- Colchicine Dans La Goutte Usage Et MésusageDocument6 pagesColchicine Dans La Goutte Usage Et MésusageAmine DounanePas encore d'évaluation

- AVENTURE DE L'ELECTRICITE - C'est Pas Sorcier Spécial Enseignant - Yoshi37Document2 pagesAVENTURE DE L'ELECTRICITE - C'est Pas Sorcier Spécial Enseignant - Yoshi37BarbaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Grille-Observation EgronDocument10 pagesGrille-Observation EgronSofia KHOUBBANEPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapitre - 1 PH201Document15 pagesChapitre - 1 PH201FanxyvPas encore d'évaluation

- Protocole Reherche 15 Sept 2023Document78 pagesProtocole Reherche 15 Sept 2023Ali AIT-MOHANDPas encore d'évaluation

- Get File PDFDocument28 pagesGet File PDFHichemPas encore d'évaluation

- 01-03 - Dec10 - Philippe Dozoul - AFNOR - FDX50-252 - Francais PDFDocument24 pages01-03 - Dec10 - Philippe Dozoul - AFNOR - FDX50-252 - Francais PDFNassima Bendjeddou100% (1)

- TP Projet D'arch 2è CibDocument12 pagesTP Projet D'arch 2è CibAMALI BlaisePas encore d'évaluation

- RTEC Cassette - R410A - InverterDocument2 pagesRTEC Cassette - R410A - InverterMohamed KhaldiPas encore d'évaluation