Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Determinants of Late Presentation For Induced Abor

Transféré par

abarvilchakTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Determinants of Late Presentation For Induced Abor

Transféré par

abarvilchakDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

WOMEN’S HEALTH

Determinants of Late Presentation for

Induced Abortion Care

Ashley Waddington, MD, MPA, FRCSC, Philip M. Hahn, MSc, Robert Reid, MD, FRCSC

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen’s University, Kingston ON

Abstract Résumé

Objective: To determine whether demographic or patient factors Objectif : Déterminer si des facteurs démographiques ou liés à la

contribute to later presentation (10 to 12 weeks’ gestational age) patiente contribuent au fait de se présenter tardivement (âge

for induced abortion in a Canadian abortion clinic. gestationnel : 10-12 semaines) dans une clinique d’avortement

canadienne pour l’obtention d’un avortement provoqué.

Methods: Women attending a hospital-based abortion clinic between

April and September 2012 were asked to complete a survey. The Méthodes : Nous avons demandé aux femmes ayant fréquenté une

characteristics of women who presented early (EPs; gestational clinique d’avortement en milieu hospitalier entre avril et septembre

age < 10 weeks) were compared with those of late presenters 2012 de remplir un questionnaire. Les caractéristiques des

(LPs; gestational age ≥ 10 weeks) using t tests for means and femmes s’étant présentées tôt (âge gestationnel < 10 semaines)

Fisher exact tests for rates. ont été comparées aux caractéristiques des femmes s’étant

présentées tard (âge gestationnel ≥ 10 semaines) au moyen de

Results: Among women referred to the clinic by a primary care

tests t (pour les moyennes) et de tests exacts de Fisher (pour les

provider, LPs were more likely than EPs to report “a delay in

taux).

obtaining a referral” (20.8% vs. 6.1%; P = 0.007). While there

was no significant difference between the groups in reporting that Résultats : Chez les femmes orientées vers la clinique par un

“someone tried to discourage [them] from having an abortion” fournisseur de soins primaires, les femmes s’étant présentées tard

(26.45% for EPs, 32.4% for LPs; P = 0.421), LPs were more étaient plus susceptibles que les femmes s’étant présentées tôt de

likely to report that discouragement “caused a delay in making signaler « un délai quant à l’obtention d’une orientation » (20,8 %

arrangements” (45.5% vs. 16.7%; P = 0.019). Of women who had vs 6,1 %; P = 0,007). Bien qu’aucune différence significative n’ait

access to a primary care provider, it was more common for the été constatée entre les groupes pour ce qui est du fait de signaler

primary care provider to be aware of the pregnancy among LPs que « quelqu’un avait tenté de les convaincre de ne pas subir un

than among EPs (80.6% vs. 63.1%; P = 0.015). avortement » (26,45 % des femmes s’étant présentées tôt, 32,4 %

des femmes s’étant présentées tard; P = 0,421), les femmes

Conclusion: Some women delay presenting for abortion because

s’étant présentées tard étaient plus susceptibles de signaler

of discouragement from friends and family. It is unclear whether

qu’une telle intervention « avait causé un délai pour ce qui est

there are educational or policy interventions that can have an

de la prise des mesures nécessaires » (45,5 % vs 16,7 %;

impact on this delay, and this warrants further study. There may be

P = 0,019). Chez les femmes qui avaient accès à un fournisseur

ways of addressing the delay in referral by primary care providers.

de soins primaires, il était plus fréquent que ce dernier soit

Further study into the causes for delay in referral for abortion is

au courant de la grossesse dans le cas des femmes s’étant

warranted.

présentées tard que dans celui des femmes s’étant présentées tôt

(80,6 % vs 63,1 %; P = 0,015).

Conclusion : Certaines femmes tardent à chercher à obtenir un

avortement en raison des efforts qui sont déployés par des amis

et des membres de la famille pour chercher à les en dissuader. La

question de savoir s’il existe des interventions pédagogiques ou

de politique pouvant exercer un effet sur ce délai demeure sans

réponse, ce qui justifie la tenue d’autres études. Il pourrait y avoir

des façons d’aborder ce délai en matière d’orientation lorsqu’il est

lié aux fournisseurs de soins primaires. La tenue d’autres études

quant aux causes de délai pour ce qui est de l’orientation vers des

services d’avortement s’avère justifiée.

Key Words: Abortion, delayed presentation, gestational age

Competing Interests: None declared.

Received on June 30, 2014

Accepted on September 10, 2014

J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015;37(1):40–45

40 l JANUARY JOGC JANVIER 2015

Determinants of Late Presentation for Induced Abortion Care

INTRODUCTION late presentation for abortion, interventions could be

developed to target those at risk of late presentation to

T he morbidity and mortality associated with elective

pregnancy termination increases with gestational age.

The risks of immediate complications such as uterine

facilitate access to abortion care earlier in gestation.

METHODS

perforation or hemorrhage, as well as later complications

such as infection, increase in a linear fashion in the first We designed a survey-based study to assess factors

trimester, and then increase exponentially in the second associated with later presentation (defined as ≥ 10 weeks’

trimester.1–5 gestational age) for induced abortion. Women attending

Challenges to finding or accessing abortion services, the only abortion clinic located in a medium-sized city

particularly those due to clinic location, restrictive legal in Ontario (with a referral population of approximately

environments, and financial barriers, may account for 1 million) between April 2012 and September 2012

delayed presentation for some women. Multiple studies have were asked to complete a survey that included questions

examined the demographic variables and patient factors designed to assess several factors previously identified

that may contribute to later (rather than early) presentation as being associated with late presentation for abortion

for abortion care.6–18 To our knowledge, only one study care. These factors included patient characteristics such

(unpublished) has taken place in a Canadian context.9 as age, occupation, parity, previous obstetric history,

contraception use, rural versus urban place of residence,

The results of studies of demographic variables that access to primary care physician, distance travelled to the

contribute to late presentation for abortion have been clinic and associated travel costs, relationship to the father

conflicting. A study in Singapore8,16 determined that of the pregnancy, and social supports.

adolescents were more likely to present late for abortion

care, while a retrospective Canadian study (unpublished)9 The clinic offers medical abortion to women presenting up

found that older age was associated with later presentation. to seven weeks’ gestational age, and surgical abortion services

A study in the United States7 suggested that adolescents up until 12 weeks’ gestational age. Women may self-refer

and economically disadvantaged women were more likely to the clinic or be referred by a health care provider. Once

to present later for abortion, but that the reasons for the woman or her health care provider has contacted the

doing so were different. Adolescents were more likely to clinic, appointments are arranged within seven to 10 days in

have a delay in recognizing that they were pregnant, while almost all cases. When women are already beyond 10 weeks’

economically disadvantaged women did not appear to have gestational age at the time they contact the clinic, an effort

a delay in recognizing their pregnancies but were more likely is made to expedite their appointment so that they can have

to have a delay between deciding to obtain an abortion their procedure performed in the clinic; if not, they would

and being able to make the arrangements to have one. need to be referred to another facility for the procedure to

Studies performed in the United States7,10 demonstrate that be performed after 12 weeks. The two facilities to which

issues related to obtaining funding for abortion care are women over 12 weeks’ gestational age are referred are 200 km

associated with delayed presentation. In a publicly funded and 260 km away, respectively. As the wait time is equal for

system, such as in Canada, concerns regarding financial all women, with the exception of those who make initial

barriers to abortion care should be less prominent. We contact with the clinic after 9+6 weeks’ gestation (who

are not aware of any studies examining whether or not would already be considered “late presenters” in this study),

challenges of reciprocal billing between provinces have a delay in obtaining an appointment in the clinic once initial

impeded Canadian women’s ability to access abortion care contact has been made would be unlikely to have changed

in a timely fashion. Studies in the United States also suggest the distribution of early and late presenters in the study or

that restrictive legal environments surrounding access to impacted the study results.

abortion care can cause delays in presentation.12 In Ontario,

where our study took place, there are few legal restrictions All women attending the clinic had had at least one

that would prevent or delay women who attempt to access ultrasound examination to confirm an intrauterine

abortion care. In some provinces in Canada, particularly pregnancy and to accurately assess gestational age. In

New Brunswick, restrictive policies regarding funding for this study all gestational ages were based on ultrasound.

abortion may play a role in delaying access to care.9,19 Gestational age on the day of the patient’s procedure was

correlated with the surveys by having a clinic nurse write

By determining whether there are demographic or patient the gestational age on the outside of each survey envelope

factors in Canadian women that are associated with as the surveys were handed in.

JANUARY JOGC JANVIER 2015 l 41

Women’s Health

Data were collected and descriptive statistical analysis was The father of the pregnancy was involved in the decision

performed using SPSS v. 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk NY). process that led to abortion in 86.7% of cases (195/225),

Determinants for early presenters (EPs, ≤ 9+6 weeks) and but was only described as being supportive of the decision

late presenters (LPs, ≥ 10 weeks) were compared using in 67.4% of cases (116/172). There were no significant

GraphPad InStat v 3.06 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, differences between EPs and LPs in either of these factors.

CA) with the t test used for comparing means, and the

Fisher exact test for comparing rates. The survey included several questions about previous

reproductive history. More than one half of the

Research ethics approval was obtained from the Queen’s respondents (62.25%, 140/225) had had at least one

University Human Research Ethics Board before initiation pregnancy before the current presentation, 79.3% of those

of the study. who had previously been pregnant (111/140) had had at

least one previous live birth, and 43.9% of respondents

(61/139) had had at least one induced abortion before their

RESULTS

current presentation. There were no significant differences

Of 255 surveys distributed, 227 were included in the between EPs and LPs in these characteristics.

analysis, giving a response rate of 89.0%. Comparing

When asked how likely they thought they were to become

gestational ages between the non-responders (n = 28)

pregnant at the time they conceived the current pregnancy,

and responders (n = 227) did not show a significant

42.7% of respondents (97/227) had thought it was “unlikely,”

difference (0.2 weeks; P = 0.347). Therefore, the findings

while 15.9% (36/227) had thought it was “impossible” for

in this survey did not appear to suffer from non-response

them to become pregnant. Fifteen percent of respondents

bias.

(34/227) had thought their risk of pregnancy was “around

In the surveys analyzed, 70% of respondents were EPs 50%,” while 18.5% (42/227) were “not sure.” Only 7.9%

(159/227), while 30% were LPs (68/227). EPs and LPs (18/227) of respondents had thought they were “likely”

did not differ significantly in demographic characteristics to conceive. Of all respondents, 14.1% (32/227) reported

(Table). The average age of respondents was 25.5 years that they “considered using emergency contraception” at

(range 14 to 46). The majority of respondents lived in the time they conceived their pregnancy, but only 46.8% of

an urban setting, with 94.3% of respondents (214/227) those women (15/32) actually used it, representing 6.6% of

indicating that they live in or near a city. Travel to the clinic all study participants. There were no differences between

was by personal car for 84.1% of respondents (190/226), EPs and LPs in these characteristics.

by taxi for 5.3% (12/226), and 7.5% (17/226) walked to the Survey respondents reported high rates of contraception

clinic. Approximately one quarter of respondents (26.3%, use at the time they conceived. More than one half

59/224) stated that they had to pay to travel to the clinic, (64.2%,145/226) reported using some form of

with a range of cost between $2 and $400 and an average contraception, with condoms being the most popular

cost of $40.95. Despite these women having to pay for method (48.3%, 70/145) and oral contraceptives being

transportation to attend the clinic, only 8.0% (18/225) the next most common method (35.2%, 51/145). Of the

agreed that “transportation was a challenge.” None of the respondents using contraception, 11.7% (17/145) were

preceding values were significantly different between EPs using “natural family planning” methods, and 15.9%

and LPs. (23/145) were using withdrawal (coitus interruptus).

Respondents were allowed to enter more than one choice

Overall, the survey respondents reported a high rate of

of contraceptive method, as some were using more than

smoking: 54.6% of respondents (124/227) stated that they

one method concurrently. There were no significant

had smoked cigarettes in the past three months. There was

differences between EPs and LPs in either their likelihood

no significant difference in the rate of smoking between

of using contraception, or the methods used.

EPs and LPs. EPs and LPs were equally likely to have

access to a primary care provider, and 93.8% of the whole Responses to five questions on the survey were significantly

cohort (213/227) had such access. In the majority of different between EPs and LPs (Table). Of women who

cases (68.2%, 144/213) the primary health care provider had access to a primary care provider, LPs were more likely

was aware of the current pregnancy. LPs were more likely than EPs to report that their primary care provider was

than EPs to report that their primary care provider was aware of the current pregnancy (80.6 vs. 63.1%; P = 0.015).

aware of the current pregnancy (80.6%, 50/62, vs. 63.1%, In women who were referred to the abortion clinic by

94/149; P = 0.015). their primary care providers, LPs were more likely than

42 l JANUARY JOGC JANVIER 2015

Determinants of Late Presentation for Induced Abortion Care

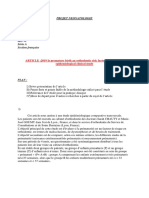

Characteristics of early and late presenters for abortion care

Early presenters Late presenters

gestational age gestational age

< 10 weeks ≥ 10 weeks

Characteristic (n = 159) (n = 68) P

Mean age of subjects in years ± SD (range) 25.8 ± 6.6 (15 to 46) 24.8 ± 5.9 (14 to 40) 0.303*

n = 158 n = 65

Living in or near a city 94.3% (150/159) 94.1% (64/68) > 0.99†

Living within the clinic city or within a half an hour drive 67.5% (106/157) 61.8% (42/68) 0.445†

Smoking in past 3 months 52.2% (83/59) 60.3% (41/68) 0.309†

Alcohol intake in past 3 months 76.1% (121/159) 48.5% (33/68) < 0.001†

Illicit drug use in past 3 months 22.9% (36/157) 41.8% (28/67) 0.006†

Having access to regular health care provider such as a 93.7% (149/159) 94.1% (64/68) 1.000†

family doctor

In those with access to regular health care provider, the 63.1% (94/149) 80.6% (50/62) 0.015†

primary care provider was aware of pregnancy

Delay in obtaining referral by primary care provider 6.1% (7/115) 20.8% (11/53) 0.007†

Using any form of contraception 65.2% (103/158) 61.8% (42/68) 0.652†

Was discouraged by someone from having an abortion 26.4% (42/159) 32.4% (22/68) 0.421†

If someone discouraged patient, this led to delay in obtaining 16.7% (7/42) 45.5% (10/22) 0.019†

abortion

Mean number of pregnancies ± SD (range) 2.5 ± 2.0 (1 to 17‡) 2.6, 1.7 (1 to 7) 0.777*

n = 158 n = 67

*t test

†Fisher exact test

‡One subject reported 17 pregnancies

EPs to report that they encountered “a delay in obtaining but this interesting finding warrants further research into

a referral” (20.8% vs. 6.1%; P = 0.007). While there was women’s knowledge about their fecundity as well as their

no statistically significant difference between the groups in knowledge of contraceptive effectiveness. In particular,

the number of women who reported that “someone tried the low rates of emergency contraception use suggest

to discourage [them] from having an abortion” (26.45% that increased knowledge and awareness of contraception

for EPs vs. 32.4% for LPs, P = 0.421), LPs were more that can be used post-coitally could reduce the unintended

likely to report that the discouragement “caused a delay in pregnancy rates in the population studied.

making arrangements for the abortion” (45.5% vs. 16.7%;

P = 0.019). EPs were more likely to report that they had Both EPs and LPs were equally likely to have been

“alcohol intake within the last 3 months” compared with discouraged from having an abortion, but LPs were more

LPs (76.1% vs. 48.5%; P = 0.001). LPs were more likely to likely to report that this influenced the time it took for

report “drug use in the last three months” compared with them to arrange their abortion. There could be several

EPs (41.8% vs. 22.9%; P = 0.006) (Table). reasons for this. It may be that the woman herself was

ambivalent about the decision and therefore more

susceptible to discouragement; it may be that the severity

DISCUSSION

of the discouragement was different between the groups,

Almost 60% of respondents in this survey had felt that or that it came from a different source, which may have

pregnancy was unlikely or impossible in their particular had a different impact on the woman. Deciding to undergo

circumstances. This could have contributed to delay in induced abortion will always be difficult, and women will

diagnosis of their pregnancy and subsequent delay in likely continue to seek advice from friends and family

obtaining abortion care, as has been reported in some prior regarding their decision. Health care providers must strive

studies.7 However, we found no difference between EPs to ensure that they are non-judgemental in their discussions

and LPs in this characteristic. Respondents were not asked with patients, and give objective and evidence-based advice

why they had thought they were unlikely to get pregnant, regarding abortion care. Policy-makers can work to ensure

JANUARY JOGC JANVIER 2015 l 43

Women’s Health

that men and women have access to unbiased advice High rates of alcohol and drug use in respondents were

and counselling, as well as to rigorous school-based sex an interesting finding, but we cannot explain why there

education programs. This will help to ensure that women was a difference in these between the EPs and LPs. The

who are struggling with their decision will not be influenced difference is likely spurious.

by rumours or myths about the procedure, but rather will

be guided by their own priorities and values. CONCLUSION

Compared with EPs, LPs were more likely to report that In this Canadian study of patient and demographic

their primary care provider was aware of their pregnancy variables contributing to later presentation for abortion

and that there was a “delay in obtaining a referral” for care, none of the factors that have been described in

abortion care from their primary health care providers. The previous studies were found to differ between EPs and

survey was not designed to determine what the delay may LPs. Factors such as distance travelled to the clinic or

have been, but, based on unsolicited write-in responses, in the cost of arranging transportation were not different

at least a few cases the delay may have been deliberately between EPs and LPs. Factors with differences between

caused by a family physician who was trying to prevent EPs and LPs in this study included alcohol consumption

a patient from obtaining an abortion. Most delays were (more common in EPs), drug use (more common in LPs),

probably not intentionally caused, but may have been due being discouraged from having an abortion, primary

to logistic challenges in booking timely appointments to be care providers’ awareness of the pregnancy, and delays

assessed by the primary health care provider, or to delays in in obtaining a referral from a primary care provider.

the administrative process of filling out a referral form and Educational or policy interventions might reduce delays in

getting it to the abortion clinic in a timely fashion. In our presentation caused by discouragement from friends and

clinic, faxed referrals receive a response within two business family. There may be ways of addressing the reported delay

days. Patients are required to have undergone an ultrasound in referral by primary care providers, including education

examination to confirm that the pregnancy is intrauterine about the opportunity for self-referral. Further study into

and to determine gestational age before their procedure the causes for delay in referral is warranted, in order to

at the abortion clinic, although the clinic will assist in ensure that women have timely access to abortion care.

arranging for the ultrasound examination if the patient’s

family doctor is unable or unwilling to arrange it. We have ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

not observed a substantial delay in accessing ultrasound

services; at our centre, women report an average wait of The authors would like to acknowledge Ms Sarah Edgerley

4.75 days to undergo ultrasound examination after either who assisted with data entry, and the staff at the Kingston

contacting the abortion clinic or contacting their health General Hospital Women’s Clinic.

care provider (range 0 to 30 days, median 7 days). There

could, however, be a delay between the ultrasound being REFERENCES

performed and the report being seen by the primary care

1. Ferris LE, McMain-Klein M, Colodny N, Fellows GF, Lamont J.

provider and incorporated into a referral to the abortion Factors associated with immediate abortion complications. CMAJ

clinic. Additional research is needed to fully understand 1996;154(11):1677–85.

the causes of delay in obtaining referrals for abortion 2. Bartlett LA, Berg CJ, Shulman HB, Zane SB, Green CA, Whitehead S,

from primary care providers. In addition, the correlation Atrash HK. Risk factors for legal induced abortion-related mortality in the

United States. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103(4):729–37.

between later presentation and higher rates of primary

care providers being aware of the pregnancy warrants 3. Cates JW, Schulz KF, Grimes DA, Tyler JCW. The effect of delay and

method choice on the risk of abortion morbidity. Fam Plann Perspect

further investigation, because this correlation is difficult to 1977;9(6):266–73.

explain. This may be an area in which health care providers 4. Heisterberg L, Kringelbach M. Early complications after induced first-

and policy makers could help decrease the likelihood of trimester abortion. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1987;66(3):201–4.

late presentation. One step that should be taken in our 5. Heisterberg L, Sonne-Holm S, Andersen JT, Hebjørn S,

community is to ensure that women are aware that they can Dyring-Andersen K, Hejl BL. Risk factors in first-trimester abortion.

self-refer to the abortion clinic and that the abortion clinic Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1982;61(4):357–60.

will arrange for them to have their ultrasound assessment 6. Buehler JW, Schulz KF, Grimes DA, Hogue CJ. The risk of serious

complications from induced abortion: do personal characteristics make

before their appointment. This would make it easier for a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1985;153(1):14–20.

women who do not have a primary care provider, or who

7. Finer LB, Frohwirth LF, Dauphinee LA, Singh S, Moore AM. Timing of

are encountering a delay in referral by their primary care steps and reasons for delays in obtaining abortions in the United States.

provider, to access abortion care more quickly. Contraception 2006;74(4):334–44.

44 l JANUARY JOGC JANVIER 2015

Determinants of Late Presentation for Induced Abortion Care

8. Lim L, Wong H, Yong E, Singh K. Profiles of women presenting for 14. Kiley JW, Yee LM, Niemi CM, Feinglass JM, Simon MA. Delays in request

abortions in Singapore: focus on teenage abortions and late abortions. for pregnancy termination: Comparison of patients in the first and second

Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2012;160(2):219–22. trimesters. Contraception 2010;81(5):446–51.

9. Brooks M, Roberts S, Waddington A. The effect of travel distance on the 15. Gallo MF, Nghia NC. Real life is different: a qualitative study of why

gestational age at which women present for abortions in New Brunswick women delay abortion until the second trimester in Vietnam. Soc Sci Med

Oral presentation, Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada 2007;64(9):1812–22.

Annual Clinical Meeting 2012; Ottawa, ON.

10. Drey EA, Foster DG, Jackson RA, Lee SJ, Cardenas LH, Darney PD. 16. Singh K, Fong YF, Loh SY. Profile of women presenting for abortions

Risk factors associated with presenting for abortion in the second in Singapore at the National University Hospital. Contraception

trimester. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107(1):128–35. 2002;66(1):41–6.

11. Kumar U, Baraitser P, Morton S, Massil H. Decision making and referral 17. Loeber O, Wijsen C. Factors influencing the percentage of second

prior to abortion: a qualitative study of women’s experiences. J Fam Plann trimester abortions in the Netherlands. Reprod Health Matters

Reprod Health Care 2004;30(1):51–4. 2008;16(31 Suppl):30–6.

12. Bitler M, Zavodny M. The effect of abortion restrictions on the timing of

18. Lee E, Ingham R. Why do women present late for induced abortion?

abortions. J Health Econ 2001;20(6):1011–32.

Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2010;24(4):479–89.

13. Foster DG, Jackson RA, Cosby K, Weitz TA, Darney PD, Drey EA.

Predictors of delay in each step leading to an abortion. Contraception 19. Shaw J. Reality check: a close look at accessing abortion services in

2008;77(4):289–93. Canadian hospitals. Ottawa: Canadians for Choice; 2006.

JANUARY JOGC JANVIER 2015 l 45

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Ojsadmin Revuemsp 2020 02 93 99Document7 pagesOjsadmin Revuemsp 2020 02 93 99Dany BodoPas encore d'évaluation

- De L'infertilité À L'assistance Médicale À La Procréation: L'infertilité en France: Données ÉpidémiologiquesDocument17 pagesDe L'infertilité À L'assistance Médicale À La Procréation: L'infertilité en France: Données Épidémiologiqueswida abrPas encore d'évaluation

- Circoncision NéonataleDocument9 pagesCirconcision NéonatalenonoPas encore d'évaluation

- 74 Lepercq WebDocument21 pages74 Lepercq Weborg20041984Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cesar I EnneDocument22 pagesCesar I EnneeliePas encore d'évaluation

- 48-Texte de L'article-118-1-10-20200522Document7 pages48-Texte de L'article-118-1-10-20200522ouologuemsekou10Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mémoire Final PDF Compressed 1Document107 pagesMémoire Final PDF Compressed 1darinbouakrifPas encore d'évaluation

- Les Soins Liés À Un Accouchement NormalDocument44 pagesLes Soins Liés À Un Accouchement NormalMónica Salazar del RíoPas encore d'évaluation

- 003l01280222v6n1 M Wade Et Al. EpisiotomieDocument10 pages003l01280222v6n1 M Wade Et Al. EpisiotomieAouf Ayouba Ousseini MaigaPas encore d'évaluation

- ExposeDocument21 pagesExposeatika oukachaPas encore d'évaluation

- Travail Original: Grossesses Rapprochées: Facteurs de Risque Et Conséquences PérinatalesDocument7 pagesTravail Original: Grossesses Rapprochées: Facteurs de Risque Et Conséquences PérinatalesRomulus GdnPas encore d'évaluation

- Suivi Prenatal IntrapartumDocument15 pagesSuivi Prenatal IntrapartumMohamad AwalsPas encore d'évaluation

- Annales - Médecine - Lyon Est - 2010-2011 - DCEM3Document28 pagesAnnales - Médecine - Lyon Est - 2010-2011 - DCEM3NiangPas encore d'évaluation

- Patient Disclosure of Medical Errors inDocument7 pagesPatient Disclosure of Medical Errors inSaba Abu FarhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Facteurs de Risque de Récidive Des Grossesses Extra-UtérinesDocument7 pagesFacteurs de Risque de Récidive Des Grossesses Extra-UtérinesMahefa Serge RakotozafyPas encore d'évaluation

- Vol 6 - Numéro 1 - 2023 - RAMS PUBLICATION - OK-114-125Document12 pagesVol 6 - Numéro 1 - 2023 - RAMS PUBLICATION - OK-114-125Bienfait KitumainiPas encore d'évaluation

- Post Abortion Care Francais Best Practice Paper April 2022Document21 pagesPost Abortion Care Francais Best Practice Paper April 2022Fabrice LutonadioPas encore d'évaluation

- Préférences, Comportements Et Besoins Non-Satisfaits en Matière de Planification FamilialeDocument19 pagesPréférences, Comportements Et Besoins Non-Satisfaits en Matière de Planification FamilialeClaurie SteciePas encore d'évaluation

- Apport de La Planification Familiale Dans La Lutte Contre Les Grossesses Non Désirées Chez Les Femmes en Âge de Procréation Dans La Zone de Santé de KASA-VUBUDocument13 pagesApport de La Planification Familiale Dans La Lutte Contre Les Grossesses Non Désirées Chez Les Femmes en Âge de Procréation Dans La Zone de Santé de KASA-VUBUcongo research papersPas encore d'évaluation

- La Consultation Preconceptionnelle: Pour Une Grossesse MeilleureDocument9 pagesLa Consultation Preconceptionnelle: Pour Une Grossesse MeilleureIJAR JOURNALPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 32Document21 pages1 32Amin-Florin El-KharoubiPas encore d'évaluation

- Audit Medical Des Deces Neonatals Selon Le Modele Des Trois Retards / Audit of The Neonatal Mortality by The Model of Three DelaysDocument6 pagesAudit Medical Des Deces Neonatals Selon Le Modele Des Trois Retards / Audit of The Neonatal Mortality by The Model of Three DelaysKOUAKOU CYPRIENPas encore d'évaluation

- Document Information AAD FamillesDocument8 pagesDocument Information AAD FamillesFrance 3 Franche-ComtéPas encore d'évaluation

- Speech MonikaDocument15 pagesSpeech MonikaDjennyPas encore d'évaluation

- Article Original: Ratovoarisoa NM, Randriamanantena SNC, Raveloharimino NH, Rabesandratana HNDocument8 pagesArticle Original: Ratovoarisoa NM, Randriamanantena SNC, Raveloharimino NH, Rabesandratana HNHarivelo SolofomananaPas encore d'évaluation

- Post Date - Post TermeDocument32 pagesPost Date - Post TermeIdiAmadou0% (1)

- Abord Du Couple InfertileDocument10 pagesAbord Du Couple InfertileElbordji100% (1)

- EtudeDocument5 pagesEtuderootPas encore d'évaluation

- Facteurs Associés Au Faible Poids de Naissance Au Centre de Santé Communautaire de Yirimadio (Mali)Document8 pagesFacteurs Associés Au Faible Poids de Naissance Au Centre de Santé Communautaire de Yirimadio (Mali)glovingimbi62Pas encore d'évaluation

- Rubéole Au Cours de La GrossesseDocument8 pagesRubéole Au Cours de La GrossesseBourhiPas encore d'évaluation

- Déclenchement Du Travail Facteurs D'échec, Morbidité Maternelle Et FoetaleDocument7 pagesDéclenchement Du Travail Facteurs D'échec, Morbidité Maternelle Et FoetaleStéphaniePas encore d'évaluation

- EXPOSEDocument9 pagesEXPOSECamille BleossiPas encore d'évaluation

- 21 Fre 01295Document7 pages21 Fre 01295Moussa Mado LainaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pouvons-Nous Éliminer Le VIH?: ScénarioDocument2 pagesPouvons-Nous Éliminer Le VIH?: ScénarioJONAAS ENRIQUE GUTIERREZ RODRIGUEZPas encore d'évaluation

- PresboDocument7 pagesPresboCahyo TriwidiantoroPas encore d'évaluation

- Agboranderson2000, Ao Meka EstherDocument6 pagesAgboranderson2000, Ao Meka EstherlevoayouPas encore d'évaluation

- Présentation TFEDocument19 pagesPrésentation TFEhoubanoemiePas encore d'évaluation

- WHO RHR 15.02 FreDocument8 pagesWHO RHR 15.02 Freornellabimuloko53Pas encore d'évaluation

- M SM2012 010 PDFDocument79 pagesM SM2012 010 PDFMokeuPas encore d'évaluation

- Niamey HDR 3.1Document13 pagesNiamey HDR 3.1ghislainadibiPas encore d'évaluation

- Resume 2Document2 pagesResume 2Gaffar SavadogoPas encore d'évaluation

- 01 Item 008 Éthique Médicale - Collège Gynéco 18Document10 pages01 Item 008 Éthique Médicale - Collège Gynéco 18chaymaedadi2026Pas encore d'évaluation

- Traitement Et Prévention Médicamenteuse de La Menace D'accouchement PrématuréDocument21 pagesTraitement Et Prévention Médicamenteuse de La Menace D'accouchement PrématuréMaraCalugaruPas encore d'évaluation

- Allaitement Et Developpement Psychosocial de LenfantDocument9 pagesAllaitement Et Developpement Psychosocial de Lenfantpatrick bokaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sujet 3 PMADocument5 pagesSujet 3 PMAaaron.comics77Pas encore d'évaluation

- 209862-Article Text-520805-1-10-20210702Document14 pages209862-Article Text-520805-1-10-20210702ornellabimuloko53Pas encore d'évaluation

- Facteurs de Risque de Deces Du Premature Dans Un Service de Reference A AbidjanDocument7 pagesFacteurs de Risque de Deces Du Premature Dans Un Service de Reference A AbidjanKOUAKOU CYPRIENPas encore d'évaluation

- Infertilité de CoupleDocument15 pagesInfertilité de Couplezazi zakiPas encore d'évaluation

- FR Potentially Inappropriate Medication Prescribing by Nurse Practitioners and Physicians FRDocument16 pagesFR Potentially Inappropriate Medication Prescribing by Nurse Practitioners and Physicians FRcelia.longuetPas encore d'évaluation

- AttachmentDocument5 pagesAttachmentastarolande1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gynécologie CESARINEDocument25 pagesGynécologie CESARINEsaraliciatinahPas encore d'évaluation

- Martial Protocole FiniDocument24 pagesMartial Protocole FininguepitchouapimartialPas encore d'évaluation

- Grossesse Et MédicamentsDocument24 pagesGrossesse Et MédicamentsJuvénal WasukundiPas encore d'évaluation

- NEONATDocument3 pagesNEONATLAALAM MOHAMMED AMINEPas encore d'évaluation

- J Jgyn 2011 01 010Document7 pagesJ Jgyn 2011 01 010Mars BrunoPas encore d'évaluation

- SUJET de Recherche MANSOUR-1Document9 pagesSUJET de Recherche MANSOUR-1donuriel48Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2013 Goetz OrianneDocument88 pages2013 Goetz OrianneFrançois DossaPas encore d'évaluation

- L'influence de la prématurité et du sexe de l'enfant sur ses perspectives de santé: Une approche transdisciplinaireD'EverandL'influence de la prématurité et du sexe de l'enfant sur ses perspectives de santé: Une approche transdisciplinairePas encore d'évaluation

- Pfeffer RGODocument6 pagesPfeffer RGOdjasmi mohamedPas encore d'évaluation

- 2015 Brochure Dpi VdefDocument32 pages2015 Brochure Dpi VdefBaranPas encore d'évaluation

- Asmae GhandourDocument1 pageAsmae GhandourMohamed FajriPas encore d'évaluation

- ARMVOP Programme 02 Décembre 2023 DDocument4 pagesARMVOP Programme 02 Décembre 2023 DARMVOPPas encore d'évaluation

- Etat Des Lieux Monde Et Cameroun Symposium DoualaDocument18 pagesEtat Des Lieux Monde Et Cameroun Symposium Doualachelcy kezetminPas encore d'évaluation

- p2 Ue English1 27 01 12Document8 pagesp2 Ue English1 27 01 12Kévin DejuanPas encore d'évaluation

- 2011 Hopital 240 LitsDocument103 pages2011 Hopital 240 LitsSzrmhl ZsmrlhPas encore d'évaluation

- TO Gamma3 Long Nail R2.0 - B0300030-FR Rev0Document20 pagesTO Gamma3 Long Nail R2.0 - B0300030-FR Rev0hccolmar copilotePas encore d'évaluation