Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Self-Assessment of Self-Efficacy

Transféré par

muslikanTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Self-Assessment of Self-Efficacy

Transféré par

muslikanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Effect of Self-Assessment on EFL Learners’

Self-Efficacy

Sasan Baleghizadeh and Atieh Masoun

This study investigated the continuous influence of self-assessment on EFL

(English as a foreign language) learners’ self-efficacy. The participants, divided

into an experimental and a control group, were 57 Iranian EFL learners in an

English-language institute. The participants’ self-efficacy was measured through

a questionnaire that was the same for both groups. Additionally, the participants

in the experimental group completed a biweekly self-assessment questionnaire

throughout the semester. The obtained data were analyzed through an Analysis

of Covariance (ANCOVA). The findings showed that the students’ self-efficacy

improved significantly in the experimental group. This suggests that applying

self-assessment on a formative basis in an EFL setting leads to increased self-effi-

cacy. This study thus highlights the pedagogical implications of self-assessment

in EFL classrooms.

Cette étude a porté sur l’influence continue de l’auto-évaluation sur l’auto-effi-

cacité des apprenants en ALE. Les participants, 57 Iraniens étudiant l’ALE dans

un institut de langue anglaise, ont été répartis parmi un groupe expérimental

et un groupe témoin. Le même questionnaire a été administré aux deux groupes

et a servi d’outil pour mesurer l’auto-efficacité des apprenants. Les membres du

groupe expérimental ont en plus complété un questionnaire d’autoévaluation

chaque deux semaines au cours du semestre. Les données ont été traitées par une

analyse de covariance (ANCOVA). Les résultats indiquent que l’auto-efficacité

des élèves s’est améliorée de façon significative dans le groupe expérimental, ce

qui porte à croire que la mise en pratique d’une auto-évaluation formative dans les

cours d’ALE entraine une amélioration de l’auto-efficacité. Cette étude fait donc

ressortir les incidences pédagogiques de l’auto-évaluation dans les cours d’ALE.

Assessment is a matter of paramount importance as it affects the whole pro-

cess of instruction. Regarding the significant role of assessment, Paris and

Paris (2001) argue that we need to know both the product and process of

learning so that we will discover what is learned, what additional effort is

required, and what skills are effective. Owing to the fact that learning and

assessment are intertwined, the growing demand for lifelong learning has led

to a reevaluation of the relationship between learning and assessment. This

reevaluation has influenced the development of the “new era of assessment”

according to Dochy, Segers, and Sluijsmans (1999).

According to Chen (2008), traditional assessment is often regarded as “the

realm of the teacher.” Chen further argues that the inadequacies of traditional

42 sasan baleghizadeh & atieh masoun

assessment attracted the attention of scholars and triggered a shift toward

alternative assessment. Alternative assessment includes performance assess-

ment, portfolio assessment, students’ self-assessment, peer-assessment, and

so forth (Huerta-Macias, 1995).

Self-assessment, as one form of measuring learners’ language competen-

cies, has attracted significant attention in foreign language education. Oscar-

son (1997) advocates learner-centred ways of determining learning. In line

with this argument, he observes that self-assessment is based on the idea

that effective learning is best achieved if students are actively engaged in the

process of learning. Thus, all other forms of assessment are subordinate to it.

An advantage of self-assessment is that it may lead to more confidence

while performing a task (Oscarson, 1997). It is hypothesized that this sense of

confidence and perceived self-mastery resulting from self-assessment would

contribute to learners’ self-efficacy. As defined by Bandura (1986), self-effi-

cacy is an individual’s judgement of his or her capabilities to complete a task

successfully. Graham (2011) also relates self-efficacy to individuals’ beliefs in

their capacity to accomplish specific tasks, assumed to have a strong influ-

ence on levels of persistence and the choices individuals make. Regarding the

importance of self-efficacy, Bandura (1984) considered self-efficacy to have a

major role in language learning by fostering or impeding learners’ progress.

In this vein, Bandura (1986) proposed that self-efficacy is more powerful than

knowledge, skill, and prior attainment.

With respect to self-assessment and self-efficacy, Bandura (1977) argues

that the sense of perceived self-mastery resulting from self-assessment con-

tributes to learners’ self-efficacy. Ross (2006) also contends that “a few studies

have demonstrated that asking students to assess their performance, without

further training, contributes to higher self-efficacy, greater intrinsic motiva-

tion, and stronger achievement” (p. 4). Consistent with this, McMillan and

Hearn (2008) suggest that self-assessment promotes both self-efficacy and

motivation. In the present article, we focus on the effect of self-assessment

on EFL learners’ level of self-efficacy, which we believe is an important area

of inquiry in language learning and teaching. Seen in another light, the criti-

cal role of self-efficacy in language learning highlights the need for more

research on the effect of self-assessment on self-efficacy in EFL contexts.

Literature Review

In the 1970s, there was a shift of focus from learning to the learner in lan-

guage teaching pedagogy, and the learner was considered to possess an ac-

tive part in the learning process and to be responsible for his or her own

learning (Anderson, Reinders, & Jones-Parry, 2004). Similarly, LeBlanc and

Painchaud (1985) have argued that learners should have an active part in the

learning cycle; this active involvement includes participation in assessment

since assessment is regarded a basic component in the educational process.

TESL CANADA JOURNAL/REVUE TESL DU CANADA 43

Volume 31, issue 1, 2013

Oscarson (1997) found that students’ involvement in all phases of learning

process, learner autonomy, the development of the concept of lifelong learn-

ing, and increased motivation are some of the benefits of self-assessment.

Self-assessment is defined by Boud and Falchikov (1989) as the process by

which students make judgements about their learning, particularly their

learning outcomes.

Past research has shown the impact of self-efficacy on learners’ achieve-

ment and proficiency (Pintrich & Schunk, 1996). The construct of self-efficacy

has a relatively brief history that began with Bandura’s (1977) seminal work

“Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Bandura

(1986) introduced self-efficacy as one of the components of social-cognitive

theory. Bandura’s (1977, 1986) social-cognitive theory is a theory of human

functioning that states that humans can control their behaviour. In other

words, Bandura’s social-cognitive theory follows the notion that human be-

ings are able to regulate their behaviour.

Self-efficacy was also explained by Bandura (1977) as the beliefs and the

confidence that one has in performing a domain-specific task at a designated

level. Bandura (1993) defined self-efficacy as “students’ beliefs in their efficacy

to regulate their own learning, master academic activities and determine their

aspirations, level of motivation, and academic accomplishment” (p. 117).

The study of self-efficacy is important inasmuch as it appears to power-

fully influence various behaviours such as attributions, choice of tasks, effort,

emotions, cognition, goals, persistence, and achievement (Bandura, 1986).

According to Bandura and Locke (2003), no mechanism of human agency is

more central or pervasive than belief in personal efficacy. “Whatever other

factors serve as guides and motivators are rooted in the core belief that one

has the power to produce desired effects; otherwise one has little incentive to

act or to persevere in the face of difficulties” (p. 87). In this vein, Mills, Pajares,

and Herron (2006) suggest that beliefs of personal efficacy are not dependent

on one’s abilities but on what one believes may be accomplished with one’s

personal skill set.

One of the most consistent findings thus far is that self-efficacy for the tar-

get language in general appears to be positively associated with achievement

as defined by course grades in the target language (Hsieh, 2008; Mills, Pajares,

& Herron, 2007). Hsieh (2008) found that self-efficacy was a good predictor of

language learning achievement. In her study, students with high self-efficacy

reported that they were more interested in learning foreign languages, had

more positive attitude, and possessed higher integrative orientation.

An individual’s belief in his or her efficacy to accomplish a given task, ac-

cording to Bandura (1977), can be developed through four primary sources:

(a) enactive mastery experiences, (b) vicarious experiences, (c) social persua-

sion, and (d) physiological and emotional states. Enactive mastery experi-

ences refer to direct experience with the task in question. They are considered

to be the strongest source of self-efficacy, according to Schunk (1991), who

44 sasan baleghizadeh & atieh masoun

introduced an individual’s own performance as the most reliable guide for

assessing efficacy.

Although not as strong as mastery experiences, but still influential, are vi-

carious experiences. When peers succeed, learners believe they can succeed,

too. When others fail, learners believe they will also fail. In the case of social

persuasion, learners have been convinced by an authoritative figure that they

are capable of developing high self-efficacy. Finally, through physiological

and emotional states, learners who tend to have low anxiety while perform-

ing a task are led into high self-efficacy.

Over the past 20 years, self-assessment has been increasingly used in

educational settings, according to de Saint Léger (2009). Blanche and Me-

rino (1989) argue that since 1976, when the first reports on self-assessment

were published, self-assessment has continued to develop as a distinct field

of study in second language (L2) learning and education.

Studies of self-assessment have investigated the rationale and methods

of using this kind of assessment as an instrument for assessing second/for-

eign language learning. Most of the studies in the field of self-assessment

deal with the accuracy of students’ self-assessment. In other words, studies

on self-assessment have mainly researched the correlations between teacher

assessment and self-assessment intended to discover the precision of self-

assessment (Blanche & Merino, 1989; Boud & Falchikov, 1989; Carr, 1977).

Since the 1990s, there has been a tendency to investigate the application

of self-assessment in classroom settings to enhance learning. A number of

researchers (e.g., Duke & Sanchez, 1994; McNamara & Deane, 1995; Rivers,

2001; Yang, 1998) were motivated to examine improving learner autonomy

through self-assessment. As self-assessment is regarded as an alternative

means of assessing learners’ ability, most of the studies in this field are quan-

titative in nature and aim at investigating the validity and reliability of self-

ratings rather than the learning process in which students are involved (de

Saint Léger, 2009).

Another line of research has been geared to investigate the application of

self-assessment in English language classes. As de Saint Léger (2009) reports,

self-perception evolves positively over time in relation to L2 fluency, vocabu-

lary, and self-confidence in speaking. Her study emphasized the potential

pedagogical advantages of self-assessment at both cognitive and affective

levels. In the same vein, Butler and Lee (2010) examined the effectiveness of

self-assessment among young EFL learners. They found that the learners’

ability to self-assess their performance improved over time. Their results re-

vealed positive but marginal effects of self-assessment on the learners’ English

performance and their confidence in learning English. Recently, Brantmeier,

Vanderplank, and Strube (2012) also examined skills-based self-assessment

across beginning, intermediate, and advanced levels of English language in-

struction. Their study offered evidence to validate the relationship between

the self-assessment instrument and the advanced learners’ achievement.

TESL CANADA JOURNAL/REVUE TESL DU CANADA 45

Volume 31, issue 1, 2013

There is some evidence that self-assessment can promote self-efficacy.

For example, Paris and Paris (2001) reviewed studies suggesting that self-

assessment is likely to promote monitoring of progress, stimulate revision

strategies, and foster feelings of self-efficacy. Similarly, Ross (2006) argued

that self-assessments that focus students’ attention on a particular aspect of

their performance contribute to positive self-efficacy beliefs.

Despite the large body of self-efficacy research found in other academic

disciplines, there are few studies that have examined the self-efficacy of for-

eign language students (Mills et al., 2006). Given that the role of students’

self-efficacy is significant in their persistence and success, it is important to

recognize ways to help learners develop high self-efficacy in language learn-

ing contexts. Hsieh (2008) suggests setting concrete and realistic goals and

providing positive but accurate feedback in order to develop self-efficacy.

Schunk (1991) also concludes that feedback for prior successes is apt to in-

crease learning efficacy. As setting concrete goals and providing feedback

are both requisites of self-assessment, it can be concluded that applying self-

assessment is likely to result in improved self-efficacy.

The Present Study

To date there has been little empirical evidence concerning the effect of self-

assessment on self-efficacy. The present study is an attempt to investigate

whether or not experiencing self-assessment would foster EFL learners’ self-

efficacy. To this end, the study aims to answer the following research ques-

tion: Does introducing self-assessment techniques significantly affect EFL

learners’ self-efficacy level?

Method

As stated above, the purpose of the present study is to find out if incorpo-

ration of self-assessment techniques in an EFL classroom would enhance

students’ self-efficacy. In order to achieve this goal, a quasi-experimental

study using two intact classes and a pretest/posttest control group design

was conducted. The independent variable manipulated in this study was a

classroom self-assessment component and the dependent variable was self-

efficacy beliefs.

In order to improve the research design of the study, the following steps

were taken. First, the treatment was withheld from the control group. In the

other words, the self-assessment component was introduced only to the ex-

perimental group. Next, the self-assessment component did not carry a grade

in order to avoid the threat of an interaction of the experimental treatment

and testing. Thus, the students did not take the self-assessment question-

naire as part of the ongoing graded evaluation of the course and therefore as

part of the final grade, and they did not feel compelled to raise their scores

46 sasan baleghizadeh & atieh masoun

to please the instructor or to improve their final grade. Besides, the experi-

mental treatment was not affected by the application of a pretest because the

self-efficacy scale measured a different construct from self-assessment. The

two instruments had different layouts, each one eliciting different informa-

tion from the learners.

Participants

The participants in the present study were 57 female adult intermediate

students who were learning English as a foreign language at an English

language institute in Yazd, Iran. The participants were selected through ad-

ministering the Preliminary English Test (PET). The participants’ average age

was 26, with a standard deviation of 3.28. They were members of four intact

classes, randomly assigned to an experimental (n = 27) and a control group (n

= 30). Only the participants in the experimental group received the treatment,

namely the self-assessment component.

Instruments

In this study, three different instruments were employed: (a) a self-assess-

ment questionnaire adapted from Blanche and Merino (1989) (see Appendix

A); (b) an English as a foreign language self-efficacy questionnaire derived

from Pintrich and De Groot (1990) (see Appendix B); and (c) a mock PET, in

order to investigate the participants’ general English proficiency level. The

PET used in this study included 67 items, consisting of 4 sections: writing,

reading, listening, and speaking. The questionnaires were translated, and

the translated versions were then checked for accuracy through eliciting the

judgement of a number of experts. They were then piloted to verify their

reliability.

English as a Foreign Language Self-efficacy Questionnaire

The self-efficacy items (Appendix B) were adapted from Pintrich and De

Groot (1990). The 9 items ask how confident students are in their ability in

their current class, or their capability to complete and concentrate on EFL

courses. The items also focus on students’ self-efficacy about their overall

performance in the English classroom, namely their confidence in attaining a

certain goal by mastering the tasks involved in performing certain language

functions. Finally, their self-efficacy toward the EFL course as a whole is mea-

sured. The items are scored using a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not at

all true of me) to 7 (very true of me). One overall English as a Foreign Language

Self-efficacy score is obtained, and total scores range from 0 to 63. Higher

scores equate with higher self-efficacy related to English as a foreign lan-

guage.

The accuracy of the translated version of the questionnaire was verified

by three English language experts. The 9 items of the scale were initially

translated into Persian. The next step involved an independent back-transla-

TESL CANADA JOURNAL/REVUE TESL DU CANADA 47

Volume 31, issue 1, 2013

tion of the Persian version into English by three MA students of TEFL. The

newly developed English version and the original one were compared and

checked by the researchers for any incompatibility. Among the psychometric

properties of the scale, the Cronbach’s alpha was obtained separately by the

researchers in order to test the adapted instruments’ internal consistency reli-

ability. The Cronbach’s alpha for the EFL self-efficacy questionnaire was 0.86,

indicating a high level of internal consistency for this instrument.

Self-assessment Questionnaire

The self-assessment questionnaire adapted from Blanche and Merino (1989)

was used in this study. In this questionnaire, students are asked to identify

classroom topics (whether grammatical, functional, or lexical) they consider

important, the main difficulties they think they had while learning the topics,

and strategies they believe may overcome these difficulties. This instrument

allows students to focus on their assets as well as their shortcomings and

makes students reflect on all the various aspects of the course (Blanche &

Merino, 1989).

The self-assessment questionnaire includes 10 items that students should

answer, covering different aspects of the course. The first section asks for

details about the topics the students find important in the past lessons, re-

quires them to rate how important they believe each topic is, and how well

they believe they can learn the topic. A 5-item scale ranging from not at all to

thoroughly/extremely is used for ratings.

In the next section, students are asked to write down the vocabulary they

have learned since the last self-assessment and then are asked to rate how

important they believe each word is, and how well they believe they can use

the word. A similar 5-item scale is used for these ratings. In the third section,

students are asked to rate their general evaluation of their gained learning

using a 5-descriptor scale ranging from learning nothing at all through a lot

in the last two weeks. In the last section, students are asked to describe their

weaknesses and the changes they would make to their study habits. They are

also asked to give their suggestions about the focus of instruction during the

following self-assessment period.

Procedure

The following procedure was followed while collecting the data. As a first

step, a Preliminary English Test (PET) was administered to measure the

participants’ English language proficiency and to make sure that both con-

trol and experimental groups were homogeneous. Then the participants in

both groups were exposed to the same instruction, as they were learning

English in the same institute. The system of instruction was homogenized

based on communicative language teaching. The learners were taught by

the same teacher based on the same textbook and syllabus and received the

same test as well as the grading system decided by the institute. Thus, it can

48 sasan baleghizadeh & atieh masoun

be concluded that both groups were in the same condition. The only differ-

ence between the two groups was that the students in the experimental group

received self-assessment training.

In the next stage, all the participants were asked to complete the ques-

tionnaire designed to identify their level of self-efficacy. The self-efficacy

questionnaire was first completed and handed in during the second week of

classes by all the participants. The next part of the research involved students

in appraising their own learning in common foreign language education con-

texts. The self-assessment techniques were utilized just for the experimental

group through the self-assessment questionnaire. The self-assessment instru-

ment consisted of items where learners situate themselves in a language task

and then evaluate their own performances. The participants were introduced

to self-assessment for the first time. The aim was to familiarize them with

self-assessment through explanation of related issues such as organization,

content, and grammar. Examples were given to explain how they could deal

with the content of the questionnaires. Moreover, the participants were asked

to self-assess for about 30–35 minutes at the end of each unit on a biweekly

basis throughout the semester (i.e., three times from the beginning of the

course, which lasted for seven weeks). They were also told that they were not

going to receive any score.

For both groups, the second self-efficacy questionnaires were completed

and handed in during the final week of classes. Once all posttest question-

naires were collected and coded, the researchers keyed in the data for analysis.

Results

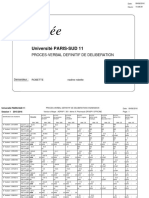

The first step in data analysis was providing a more comprehensive view

of the sample in both groups. Descriptive statistics including mean, range,

standard deviation, and minimum and maximum scores are presented below

(Table 1).

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics for Self-Efficacy

N Mean SD Range Minimum Maximum

Experimental group

Pretest 27 44.40 7.58 26 31.00 57.00

Posttest 27 48.96 6.98 24 36.00 60.00

Control group

Pretest 30 43.86 7.99 26 32.00 58.00

Posttest 30 44.63 9.03 34 22.00 56.00

As Table 1 shows, the level of learners’ self-efficacy in the experimental

group improved. However, to demonstrate that this is a significant improve-

TESL CANADA JOURNAL/REVUE TESL DU CANADA 49

Volume 31, issue 1, 2013

ment, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used. The ANCOVA was

used to standardize the pretest self-efficacy scores on both groups (i.e., pre-

test self-efficacy scores served as the covariate). The use of ANCOVA pro-

vides researchers with a technique that allows one to more appropriately

analyze the data. In other words, a quasi-experimental design leaves a study

more vulnerable to threats of validity than a full experimental design; this

vulnerability can be minimized by applying an ANCOVA (Dörnyei, 2007).

Dörnyei further argues that a special case of the use of ANCOVA occurs in

quasi-experimental designs when the posttest scores of the control and the

treatment groups are compared while the pretest scores are controlled as the

covariate.

Prior to conducting data analysis, the assumptions for an ANCOVA were

examined. There are a number of assumptions associated with ANCOVA

(Pallant, 2001). The data were screened for violations of normality, linearity,

homogeneity of regression slopes, and homogeneity of variances.

To investigate normality of distribution, the self-efficacy scores were sub-

jected to the application of One-Sample Kolomogorov-Smirnov (K-S) tests for

each group. This assesses the normality of the distribution of scores for the

two groups. The normality of distribution is one of the essential and funda-

mental assumptions of parametric tests such as ANCOVA. The results of the

application of K-S tests—in this case significance values of 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, and

0.9 for the groups—suggest that the assumption of normality is not violated.

(A non-significant result, sig. value of more than .05, indicates normality.)

The second assumption is the linear relationship between the dependent

variable and the covariate. ANCOVA assumes that the relationship between

the dependent variable and each of the covariates is linear. Another assump-

tion is homogeneity of regression slopes. This assumption requires that the

relationship between the covariate and dependent variable for each of the

groups be the same. There should be no interaction between the covariate

and the treatment or experimental manipulation. The assessment of this as-

sumption involves investigating whether there is a statistically significant

interaction between the treatment and the covariate. If the interaction is sig-

nificant at 0.05 alpha level, then the assumption is violated. Table 2 shows

that the sig. or the probability value is 0.52, which is above 0.05. Therefore,

the assumption of homogeneity of regression slopes is not violated.

Table 2

Tests of Between-Subjects Effects

Source Type III sum of squares df MS F sig

Treatment 69.86 1 69.86 2.00 .16

Pretest 1712.68 1 1712.68 49.03 .001

Treatmenta 14.14 1 14.14 .40 .52

aInteraction between treatment and the covariate (pre-test score).

50 sasan baleghizadeh & atieh masoun

The last assumption, test of homogeneity of variances, was also checked.

Using Levene’s Test of Equality of Error Variances, we examined whether the

variances in scores are the same for each of the groups, checking that the as-

sumption of equality of variances has not been violated. If the value is smaller

than 0.05 (and therefore significant), this means that the variances are not

equal and the assumption has been violated. In this case, the sig. value is 0.78,

which is much greater than 0.05, so the assumption has not been violated.

To answer the research question of this study—namely whether intro-

ducing self-assessment techniques significantly affects EFL learners’ self-

efficacy level—an ANCOVA was used to compare the posttests (Table 3). As

the sig. value for the independent variable (treatment) is .001, which is less

than 0.05, the result shows that the scores obtained by both groups on the

dependent variable (self-efficacy) differ significantly. In other words, there

is a significant difference in the self-efficacy scores for participants in both

groups, suggesting that the self-assessment training had a significant impact

on the participants’ level of self-efficacy in the experimental group. The eta

squared value for the independent variable (treatment) is 0.3 indicating that

30 percent of the variance in the dependent variable is explained by the in-

dependent variable.

Table 3

Tests of Between-Subjects Effects

Source Type III df Mean F sig Partial

sum of squares eta square square

Pre-test 1766.53 1 1766.53 51.13 .001 .48

Treatment 769.03 1 769.03 22.26 .001 .29

Error 1865.39 54 34.54

Discussion

This study investigated the effect of self-assessment on EFL learners’ self-effi-

cacy. To investigate the research question “Does introducing self-assessment

techniques significantly affect EFL learners’ self-efficacy level?” an ANCOVA

was used. Table 3 reveals that implementation of a self-assessment compo-

nent on a formative and regular basis enhances EFL learners’ self-efficacy.

This was one of the major findings of the study, which demonstrated that

the participants in the experimental group had a significantly higher level

of self-efficacy compared to their peers in the control group at the end of the

treatment period.

These results are consistent with the theoretical and empirical studies that

contribute to the significance of self-assessment in language teaching. The

results extend the findings of previous studies (Butler & Lee, 2010; de Saint

Léger, 2009). The results of the present study confirm the findings of de Saint

Léger (2009), who claims that as a result of self-assessment, self-perception

TESL CANADA JOURNAL/REVUE TESL DU CANADA 51

Volume 31, issue 1, 2013

evolves positively over time in relation to fluency, vocabulary, and self-con-

fidence in speaking in L2. Her study emphasized the potential pedagogical

advantages of self-assessment at both cognitive and affective levels. These

results are also in line with the findings of Butler and Lee (2010), who found

that learners’ ability to self-assess their performance improved over time as

they concluded that self-assessment left a positive but marginal effect on Eng-

lish learners’ performance and confidence.

One explanation for the beneficial effect of self-assessment on self-effi-

cacy is the belief that self-assessment may lead to a comfortable approach

to specific-related materials and more confidence while performing a task

(Oscarson, 1997). In other words, self-assessment may have helped students

with respect to their self-efficacy through the sense of self-mastery. As Ban-

dura (1977) argues, the sense of perceived self-mastery resulting from one’s

self-assessment leads to learners’ self-efficacy. Thus, it can be concluded that

this sense of confidence and perceived self-mastery as the result of self-as-

sessment contributes to increasing the learners’ self-efficacy.

In the self-assessment questionnaire used in this study, students were

asked to state the topics they had learned and how much they had learned in

relation to each topic covered during instruction. As students restated what

and how well they had learned, they were apt to increase the level of enac-

tive mastery experience, often defined as the learner’s own performance and

direct experience, which is also considered the main source of self-efficacy.

These effects of self-assessment are likely to make students interpret their

performance as a mastery experience, which is the most powerful source of

self-efficacy according to Bandura (1977).

Ross (2006) also argued that self-assessment can contribute to self-efficacy

through mastery and vicarious experiences. He explains that self-assessment

focuses students’ attention on particular aspects of their performance, rede-

fines the standards students use to decide whether they were successful, and

structures teacher feedback to reinforce positive reactions to the successful

performance. Because the questionnaire used in this study made learners

focus their attention on particular aspects of their performance by requiring

them to identify and state the goals and important topics and to redefine the

criteria by evaluating themselves against these goals and criteria, the learners

were led to heightened self-efficacy. Consequently, the teacher provided pos-

itive feedback for successful performance. Therefore, it can be concluded that

the self-assessment questionnaire in this study has been effective in learners’

improved self-efficacy based on Ross’s argument.

With respect to vicarious experience, Bandura (1977) argues that self-

assessment can also contribute to self-efficacy through classroom discussion

of exemplars, and providing examples of successful experience by students’

peers. These procedures were done in this study while the instructor was

conducting the self-assessment process; she presented the students’ perfor-

mances, especially the successful ones. Therefore, these successful examples

52 sasan baleghizadeh & atieh masoun

could be regarded as the source of vicarious experience. Finally, Bandura

(1977) concludes that the willingness of teachers to share the control of as-

sessment gives students a sense of ability and responsibility. Thus self-assess-

ment can be considered as an important source of positive efficacy.

In this study, self-assessment was done as formative rather than sum-

mative assessment. As Geeslin (2003) contends, evaluation should present

regular feedback, not in the summative form, but as the formative part of the

procedure. This idea is based on the fact that applying self-assessment as a

formative tool helps learners recognize their strengths and weaknesses and

hence improve specific aspects of their performance.

Moreover, providing regular feedback and focusing on improvement

are also significant for improving the level of self-efficacy. Schunk (1991) ob-

serves that feedback for prior successes is likely to increase learning efficacy.

Regular implementation of self-assessment on a formative basis provides the

opportunity for discussion of the performance itself, clarification of the be-

haviours associated with successful performance, and development of indi-

vidual work. Finally, it should be noted that this questionnaire also enhances

interaction between the instructor and learners, as a result of which learners

receive feedback for further improvement of their work.

Conclusion

The goal of the present study was to investigate the effect of self-assessment

on EFL learners’ self-efficacy. The findings confirmed the pedagogical value

of self-assessment. Because self-efficacy is regarded as a significant element in

the process of language learning, the issue of improving this element through

self-assessment is addressed in the present study. To investigate the hypoth-

esized pedagogical value of self-assessment, this study examined the effect

of self-assessment on EFL learners’ self-efficacy to see if the participants’

self-efficacy would improve at the end of the treatment period. The findings

revealed that EFL learners’ self-efficacy level indicated a significant improve-

ment due to applying the self-assessment component over time. This result

showed that applying regular self-assessment as a formative assessment tech-

nique heightens the learners’ level of self-efficacy in an EFL context. In other

words, students’ perceived capability to learn English as a foreign language

increases by assessing themselves on a regular basis.

The most direct implication of the findings of this study is related to lan-

guage teaching. Given the positive findings of the present study, language

teachers are strongly recommended to include comprehensive self-assess-

ment in their teaching practice. They can integrate various kinds of self-as-

sessment practice (such as the one applied in this study) in their instruction.

Teachers can also make use of this strategy as a scaffolding tool. In the other

words, they can apply self-assessment means after each unit of work in order

to focus the learners’ attention on a target issue in the process of instruction.

TESL CANADA JOURNAL/REVUE TESL DU CANADA 53

Volume 31, issue 1, 2013

The use of various kinds of self-assessment techniques along with ap-

propriate instructional feedback can improve students’ self-efficacy. As a

matter of fact, self-assessment can satisfy pedagogical promises if conducted

appropriately. Comprehensive guidelines are presented in the literature by

Oscarson (1989) and Brown and Hudson (1998). Lastly, among the avail-

able assessment tools, self-assessment is the one that fosters opportunities

for interaction among the teacher and the learner. Therefore, this form of

assessment is regarded as an optimal method of measurement for authentic

communication.

Further research, however, needs to be conducted to shed further light on

the beneficial effects of self-assessment. For example, self-assessment might

be related to an individual’s cultural background. Thus, it will be worthwhile

to investigate self-assessment data collected from learners in different cul-

tures and compare them with each other. Similar studies can be conducted

with learners from different social backgrounds. Finally, the effect of self-

assessment on self-efficacy for different language skills can be investigated

in order to learn more about the nature of reading self-efficacy, writing self-

efficacy, listening self-efficacy, and speaking self-efficacy.

The Authors

Sasan Baleghizadeh is an associate professor of TEFL at Shahid Beheshti University (G.C.) in

Tehran, Iran, where he teaches courses in applied linguistics, syllabus design, and materials

development. He is interested in investigating the role of interaction in English language teach-

ing and issues related to materials development. His published articles appear in numerous

international journals including TESL Reporter, TESL Canada Journal, ELT Journal, and Language

Learning Journal.

Atieh Masoun holds an MA degree in TEFL from Shahid Beheshti University (G.C.) in Tehran,

Iran. She has many years of experience in teaching English as a foreign language. Her research

interest is exploring the effect of self-assessment on EFL learners’ classroom achievement.

References

Anderson, H., Reinders, H., & Jones-Parry, J. (2004). Self-access: Positioning, pedagogy and fu-

ture directions. Prospect, 19(3), 15–26.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological

Review, 84(2), 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1984). Recycling misconceptions of perceived self-efficacy. Cognitive Therapy and

Research, 8(3), 231–255.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational

Psychologist, 28(2), 117–148.

Bandura, A., & Locke, E. A. (2003). Negative self-efficacy and goal effects revisited. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 88(1), 87–99.

Blanche, P., & Merino, B. J. (1989). Self-assessment of foreign-language skills: Implications for

teachers and researchers. Language Learning, 39(3), 313–338.

Boud, D., & Falchikov, N. (1989). Quantitative studies of student self-assessment in higher edu-

cation: A critical analysis of findings. Higher Education, 18(5), 529–549.

54 sasan baleghizadeh & atieh masoun

Brantmeier, C., Vanderplank, R., & Strube, M. (2012). What about me? Individual self-assessment

by skill and level of language instruction. System, 40(1), 144–160.

Brown, J. D., & Hudson, T. (1998). The alternatives in language assessment. TESOL Quarterly,

32(4), 653–675.

Butler, Y. G., & Lee, J. (2010). The effects of self-assessment among young learners of English.

Language Testing, 27(1), 5–31.

Carr, R. A. (1977). The effects of specific guidelines on the accuracy of student self-evaluation.

Canadian Journal of Education, 2(4), 65–77.

Chen, Y. M. (2008). Learning to self-assess oral performance in English: A longitudinal case

study. Language Teaching Research, 12(2), 235–262.

de Saint Léger, D. (2009). Self-assessment of speaking skills and participation in a foreign lan-

guage class. Foreign Language Annals, 42(1), 158–178.

Dochy, F., Segers, M., & Sluijsmans, D. (1999). The use of self-, peer and co-assessment in higher

education: A review. Studies in Higher Education, 24(3), 331–350.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Duke, C. R., & Sanchez, R. (1994). Giving students control over writing assessment. English

Journal, 83(4), 47–53.

Geeslin, K. L. (2003). Student self-assessment in the foreign language classroom: The place of au-

thentic assessment instruments in the Spanish language classroom. Hispania, 86(4), 857–868.

Graham, S. (2011). Self-efficacy and academic listening. Journal of English for Academic Purposes,

10(2), 113–117.

Hsieh, P.-H. (2008). Why are college foreign language students’ self-efficacy, attitude, and moti-

vation so different? International Education, 38(1), 76–94.

Huerta-Macias, A. (1995). Alternative assessment: Response to commonly asked questions.

TESOL Journal, 5(1), 8–11.

LeBlanc, R., & Painchaud, G. (1985). Self-assessment as a second language placement instrument.

TESOL Quarterly, 19(4), 673–687.

McMillan, J. H., & Hearn, J. (2008). Student self-assessment: The key to stronger student motiva-

tion and higher achievement. Educational Horizons, 87(1), 40–49.McNamara, M. J., & Deane,

D. (1995). Self-assessment activities: Toward language autonomy in language learning.

TESOL Journal, 5(1), 17–21.

Mills, N., Pajares, F., & Herron, C. (2006). A reevaluation of the role of anxiety: Self-efficacy,

anxiety, and their relation to reading and listening proficiency. Foreign Language Annals,

39(2), 276–295.

Mills, N., Pajares, F., & Herron, C. (2007). Self-efficacy of college intermediate French students:

Relation to achievement and motivation. Language Learning, 57(3), 417–442.

Oscarson, M. (1989). Self-assessment of language proficiency: Rationale and applications.

Language Testing, 6(1), 1–13.

Oscarson, M. (1997). Self-assessment of foreign and second language proficiency. In C. Clapham

& D. Corson (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education: Language testing and assessment

(Vol. 7, pp. 175–187). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Pallant, J. (2001). SPSS survival manual. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Paris, S. G., & Paris, A. H. (2001). Classroom applications of research on self-regulated learning.

Educational Psychologist, 36(2), 89–101.

Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of

classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 33–40.

Pintrich, P. R., & Schunk, D. H. (1996). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Rivers, W. P. (2001). Autonomy at all costs: An ethnography of metacognitive self-assessment

and self-management among experienced language learners. Modern Language Journal, 85(2),

279–290.

Ross, J. A. (2006). The reliability, validity, and utility of self-assessment. Practical Assessment,

Research and Evaluation, 11(10), 1–13.

TESL CANADA JOURNAL/REVUE TESL DU CANADA 55

Volume 31, issue 1, 2013

Schunk, D. H. (1991). Self-efficacy and academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 26(3–4),

207–231.

Yang, N.-D. (1998). Exploring a new role for teachers: Promoting learner autonomy. System,

26(1), 127–135.

Appendix A

Self-Assessment Questionnaire

1. In the past few lessons (days, weeks), we/I have studied/practiced/worked

on:

a) _________________________________

b) _________________________________

c) _________________________________

d) _________________________________

e) _________________________________

f) _________________________________

Tip: Fill in the empty spaces with topics and areas of study that are rele

vant to your case, for example:

a) Pronunciation of words containing the sound /ð/

b) How to greet people

c) Questions with do/does

(The “new words” you have used will be covered under items 3 and 4, so

please don’t include vocabulary in this section.)

2. In your estimation, how well can you deal with the topics you listed in

Section 1?

Not at all To some extent Fairly well Very well Thoroughly

a) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

b) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

c) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

d) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

e) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

f) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

3. On reflection, to what extent do you find the topics you listed in Section 1

important in relation to your own needs?

Not at all Not very Fairly Very Extremely

important important important important important

a) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

b) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

c) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

d) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

e) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

f) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

56 sasan baleghizadeh & atieh masoun

4. We/I have also come across new words of the following type, or within

the following type, or within the following subject areas(s): (write down

your native language equivalents if it’s easier for you.)

a) ___________________________________________________

b) ___________________________________________________

c) ___________________________________________________

d) ___________________________________________________

5. In your estimation, how well do you know the vocabulary/areas you men-

tioned in Section 4?

Not at all To some extent Fairly well Very well Thoroughly

a) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

b) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

c) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

d) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

6. On reflection, to what extent do you find the vocabulary/areas in Section 4

important in relation to your own needs?

Not at all Not very Fairly Very Extremely

important important important important important

a) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

b) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

c) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

d) ----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

7. Summarizing the past few lessons (days, weeks) we/I feel that we/I have

learned:

Nothing at all Very little A little Enough A lot

----------- ----------- ----------- ----------- -----------

8. Looking back, I realize that I should change my study habits/learning ap-

proach/priorities in the following way:

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

9. Overall, I think my weaknesses are:

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

TESL CANADA JOURNAL/REVUE TESL DU CANADA 57

Volume 31, issue 1, 2013

10. I would want to see instruction in the next few lessons (days, weeks) fo-

cused on the following points/skills/areas:

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

Appendix B

Self-Efficacy Questionnaire

1. Compared with other students in this class, I expect to do well.

2. I’m certain I can understand the ideas taught in this course.

3. I expect to do very well in this class.

4. Compared with others in this class, I think I’m a good student.

5. I am sure I can do an excellent job on the problems and tasks assigned for

this class.

6. I think I will receive a good grade in this class.

7. My study skills are excellent compared with others in this class.

8. Compared with other students in this class, I think I know a great deal

about the subject.

9. I know that I will be able to learn the material for this class.

Adapted from Pintrich and De Groot (1990).

Scale ranges from 0 (not at all true of me) to 7 (very true of me).

58 sasan baleghizadeh & atieh masoun

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Évaluations formative et certificative des apprentissages: Enjeux pour l'enseignementD'EverandÉvaluations formative et certificative des apprentissages: Enjeux pour l'enseignementPas encore d'évaluation

- R9 PDFDocument23 pagesR9 PDF20040279 Nguyễn Thị Hoàng DiệpPas encore d'évaluation

- Admin, AJER1593-GalleyDocument15 pagesAdmin, AJER1593-GalleyRahil99 MahPas encore d'évaluation

- Admin, MS 1114R-GalleyDocument14 pagesAdmin, MS 1114R-GalleySwee KhenPas encore d'évaluation

- S0 Recherches Psycho V2017Document4 pagesS0 Recherches Psycho V2017AbdouDrdarkPas encore d'évaluation

- BTL-PPLDocument14 pagesBTL-PPLNguyễn Ngọc LanPas encore d'évaluation

- Med 625 ArticleDocument23 pagesMed 625 Articleapi-259622463Pas encore d'évaluation

- La Relation Entre Les Attitudes Et La MoDocument23 pagesLa Relation Entre Les Attitudes Et La MoRiad HakimPas encore d'évaluation

- MEMOIRE Copie FinaleDocument82 pagesMEMOIRE Copie Finalebenarafa azzaPas encore d'évaluation

- La Motivation Chez Les Etudiants - ProfDocument6 pagesLa Motivation Chez Les Etudiants - Profmirela rusuPas encore d'évaluation

- Mindfulness For Children and Youth LiteratureReview PDFDocument20 pagesMindfulness For Children and Youth LiteratureReview PDFlmnf717086Pas encore d'évaluation

- Prim 012Document11 pagesPrim 012Magda BerindeiPas encore d'évaluation

- Lidil 4198Document14 pagesLidil 4198florachauveauPas encore d'évaluation

- Sources de Sa Motivation Dans Les Cours de FrançaisDocument4 pagesSources de Sa Motivation Dans Les Cours de FrançaisManon DournelPas encore d'évaluation

- Avantage Des Classes JumelesDocument1 pageAvantage Des Classes JumelesLassana LegrandPas encore d'évaluation

- La Motivation ScolaireDocument8 pagesLa Motivation ScolaireMourad lahmarPas encore d'évaluation

- Penso 02TQA00UFB3 THDocument208 pagesPenso 02TQA00UFB3 THŘachida LkPas encore d'évaluation

- REEM 24 Motivation PDFDocument21 pagesREEM 24 Motivation PDFCatherine BouthillettePas encore d'évaluation

- L'évaluation Dans L'écoleDocument15 pagesL'évaluation Dans L'écolejinchuuriki27100% (1)

- Self RegulationDocument34 pagesSelf RegulationGerònim VimoPas encore d'évaluation

- Effectiveness in L2 VocabularyDocument23 pagesEffectiveness in L2 VocabularybalpomoreliPas encore d'évaluation

- La Motivation en Contexte Scolaire 1Document23 pagesLa Motivation en Contexte Scolaire 1AbdoulkaderPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 Article Canada Démarche CollaborativeDocument15 pages2016 Article Canada Démarche Collaborativemarion77chapuisPas encore d'évaluation

- Le Socioconstructivisme CLE Et Blogue PDFDocument5 pagesLe Socioconstructivisme CLE Et Blogue PDFTierno Hady NiangalyPas encore d'évaluation

- Adapting The CEFR For The Classroom Assessment of Young Learners' WritingDocument22 pagesAdapting The CEFR For The Classroom Assessment of Young Learners' WritingAzurawati WokZakiPas encore d'évaluation

- La MotivationDocument8 pagesLa MotivationFaniry RaheriveloPas encore d'évaluation

- Approche Par ObjectifsDocument5 pagesApproche Par ObjectifsSaddek KHELIFAPas encore d'évaluation

- Ree 6698 140 174Document35 pagesRee 6698 140 174azoozPas encore d'évaluation

- 1845 AcDocument3 pages1845 Accathyaffognon37Pas encore d'évaluation

- Madiha Senouci PDFDocument18 pagesMadiha Senouci PDFLareina AssoumPas encore d'évaluation

- StudentSelfAssessment FRDocument8 pagesStudentSelfAssessment FRJulien TousPas encore d'évaluation

- L'Évaluation Active Ou Le Mode Opératoire ÉvaluatifDocument9 pagesL'Évaluation Active Ou Le Mode Opératoire Évaluatifmouram07Pas encore d'évaluation

- BANDURA TheorieDocument4 pagesBANDURA TheorieBouabidiPas encore d'évaluation

- La Théorie D'albert BANDURA: SynthèseDocument4 pagesLa Théorie D'albert BANDURA: Synthèsecéline DPas encore d'évaluation

- Perrenoud - Evaluation FormativeDocument29 pagesPerrenoud - Evaluation FormativeKellynhaMoraesPas encore d'évaluation

- Planification & Décision Chez Les EnseignantsDocument28 pagesPlanification & Décision Chez Les EnseignantsRAKOTOMALALAPas encore d'évaluation

- Avant Projet 1Document6 pagesAvant Projet 1abir laz100% (1)

- Tiberghien, Ross & Sensevy (2014) The Evolution of Classroom Physics KnowledgeDocument32 pagesTiberghien, Ross & Sensevy (2014) The Evolution of Classroom Physics Knowledgeesteel7Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2.2 La Motivation Des ApprenantsDocument2 pages2.2 La Motivation Des ApprenantsFouzya EssarghiniPas encore d'évaluation

- Sonja Knutson Experiential LearningDocument13 pagesSonja Knutson Experiential Learningsamuel_mckay_715Pas encore d'évaluation

- Travail Reflexif FinalDocument10 pagesTravail Reflexif FinalAmany BahgatPas encore d'évaluation

- Enseignants Débutants Et Pratiques de Gestion de ClasseDocument18 pagesEnseignants Débutants Et Pratiques de Gestion de ClasseOptimiste OptimistePas encore d'évaluation

- Candaset EneauversionauteursDocument16 pagesCandaset EneauversionauteursAngélica María Casallas BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Données Probantes Dans La FormationDocument20 pagesDonnées Probantes Dans La FormationJeanPas encore d'évaluation

- Pédagogie de La Classe Inversée: /spip/spip - PHPDocument6 pagesPédagogie de La Classe Inversée: /spip/spip - PHPYassine BelaaliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rapport cm1Document1 pageRapport cm1Mohammed AminePas encore d'évaluation

- 1) Govaerts, Gregoire (2004) - Stressfull Academic SituationsDocument11 pages1) Govaerts, Gregoire (2004) - Stressfull Academic SituationsFiqah Soraya AlhaddarPas encore d'évaluation

- Classe InverséeDocument6 pagesClasse InverséeNic KesPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - CAP - Qu'est Ce Que C'estDocument2 pages1 - CAP - Qu'est Ce Que C'estSEGPA OUANGANIPas encore d'évaluation

- Work-Study Congruence ScaleDocument18 pagesWork-Study Congruence Scalekafi naPas encore d'évaluation

- Article-La-motivation SB ISITDocument16 pagesArticle-La-motivation SB ISITEmotik SAPas encore d'évaluation

- Approche Par ObjectifsDocument3 pagesApproche Par ObjectifsFatima Idrissi Zaki100% (2)

- Uao Syllabus 2020 TestingDocument37 pagesUao Syllabus 2020 Testingmeblin.mnPas encore d'évaluation

- APONT.L'Évaluation Formative - Perrenoud, Ph.Document3 pagesAPONT.L'Évaluation Formative - Perrenoud, Ph.Isabel PinheiroPas encore d'évaluation

- ED619325 Quality CircleDocument12 pagesED619325 Quality Circle207235001Pas encore d'évaluation

- Projet Final IplacexDocument16 pagesProjet Final IplacexScribdTranslationsPas encore d'évaluation

- Galvani Autoformation Existentielle Recherche Revue Présences Vol1Document11 pagesGalvani Autoformation Existentielle Recherche Revue Présences Vol1Pascal GalvaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Les Effets Des Activités Extra-Scolaires Sur La Performance Académique Des ÉtudiantsDocument47 pagesLes Effets Des Activités Extra-Scolaires Sur La Performance Académique Des ÉtudiantsScribdTranslations0% (1)

- Synthèse Didactique G6Document5 pagesSynthèse Didactique G6zouhirdaoudi1090Pas encore d'évaluation

- Polycopié de DidactiqueDocument13 pagesPolycopié de DidactiqueMOHAMED EL BAKHCHOUCHIPas encore d'évaluation

- Feuilletage Theorie Pratique Geotech T1 2ed BDocument64 pagesFeuilletage Theorie Pratique Geotech T1 2ed BbouananiPas encore d'évaluation

- PV - Dfasp1Document40 pagesPV - Dfasp1Estelle BarbatPas encore d'évaluation

- Mino Dora DinuDocument24 pagesMino Dora DinuCiprian Constantin100% (1)

- Mon Projet de RechercheDocument5 pagesMon Projet de RechercheMehdi AlpesPas encore d'évaluation

- Le Plan Marketing PDFDocument240 pagesLe Plan Marketing PDFRachid El Faiz100% (1)

- Variable Etat PDFDocument103 pagesVariable Etat PDFIRBAHPas encore d'évaluation

- Brochure Diu Cesam 2019-20Document16 pagesBrochure Diu Cesam 2019-20maximixPas encore d'évaluation

- African Development Review Vol 29 PDFDocument150 pagesAfrican Development Review Vol 29 PDFj.assokoPas encore d'évaluation

- Réussir Vos Projets Daffaires en AfriqueDocument560 pagesRéussir Vos Projets Daffaires en AfriqueBuoreima CissePas encore d'évaluation

- Exam Méthodologie. Kenza El OumamiDocument6 pagesExam Méthodologie. Kenza El Oumamim.hamidiPas encore d'évaluation

- Memoire M2 MEEFA Lisa RibetDocument68 pagesMemoire M2 MEEFA Lisa RibetMyProf EpsPas encore d'évaluation

- CV Colonel Fakraoui AnisDocument8 pagesCV Colonel Fakraoui Anisanon_726067978Pas encore d'évaluation

- Recherche Clinique Méthodologie StatistiqueDocument8 pagesRecherche Clinique Méthodologie StatistiqueYacine Tarik AizelPas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus de Organistion Des Entreprises Et Les Elements de ManagementDocument37 pagesSyllabus de Organistion Des Entreprises Et Les Elements de ManagementOlga AdroPas encore d'évaluation

- Exosup StatsDocument8 pagesExosup StatsRené AndreescuPas encore d'évaluation

- Examen3+Solution Méthodologie de La RédactionDocument2 pagesExamen3+Solution Méthodologie de La Rédactiondjihane haouesPas encore d'évaluation

- Cours Enquête Socio 2021 - 22 PDFDocument22 pagesCours Enquête Socio 2021 - 22 PDFfarida Hema100% (1)

- Béton de SableDocument121 pagesBéton de Sableomarout100% (4)

- Le Soleil D'algerie - Algérie - Le Prof Qui Donnait Un Cours Magistral Sur Le Plagiat Pris en Flagrant Délit De... Plagiat.Document4 pagesLe Soleil D'algerie - Algérie - Le Prof Qui Donnait Un Cours Magistral Sur Le Plagiat Pris en Flagrant Délit De... Plagiat.yacine26Pas encore d'évaluation

- Recherche 1Document10 pagesRecherche 1gerard1993Pas encore d'évaluation

- Corrigé Methodo Février 10Document13 pagesCorrigé Methodo Février 10steelhalloweenPas encore d'évaluation

- Article 51 Guide Methodologique Evaluation Des Projets Articles 51 Document CompletDocument55 pagesArticle 51 Guide Methodologique Evaluation Des Projets Articles 51 Document CompletCANTYPas encore d'évaluation

- td1 Equipef Rapport-4Document16 pagestd1 Equipef Rapport-4api-633161295Pas encore d'évaluation

- DELF B1 Production Orale - 150 sujets pour réussirD'EverandDELF B1 Production Orale - 150 sujets pour réussirÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (7)

- Hypnotisme et Magnétisme, Somnambulisme, Suggestion et Télépathie, Influence personnelle: Cours Pratique completD'EverandHypnotisme et Magnétisme, Somnambulisme, Suggestion et Télépathie, Influence personnelle: Cours Pratique completÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (8)

- Vocabulaire DELF B2 - 300 expressions pour reussirD'EverandVocabulaire DELF B2 - 300 expressions pour reussirÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (7)

- Neuropsychologie: Les bases théoriques et pratiques du domaine d'étude (psychologie pour tous)D'EverandNeuropsychologie: Les bases théoriques et pratiques du domaine d'étude (psychologie pour tous)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Améliorer votre mémoire: Un Guide pour l'augmentation de la puissance du cerveau, utilisant des techniques et méthodesD'EverandAméliorer votre mémoire: Un Guide pour l'augmentation de la puissance du cerveau, utilisant des techniques et méthodesÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Le livre de la mémoire libérée : Apprenez plus vite, retenez tout avec des techniques de mémorisation simples et puissantesD'EverandLe livre de la mémoire libérée : Apprenez plus vite, retenez tout avec des techniques de mémorisation simples et puissantesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (6)

- Comment développer l’autodiscipline: Résiste aux tentations et atteins tes objectifs à long termeD'EverandComment développer l’autodiscipline: Résiste aux tentations et atteins tes objectifs à long termeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (7)

- La Pensée Positive en 30 Jours: Manuel Pratique pour Penser Positivement, Former votre Critique Intérieur, Arrêter la Réflexion Excessive et Changer votre État d'Esprit: Devenir une Personne Consciente et PositiveD'EverandLa Pensée Positive en 30 Jours: Manuel Pratique pour Penser Positivement, Former votre Critique Intérieur, Arrêter la Réflexion Excessive et Changer votre État d'Esprit: Devenir une Personne Consciente et PositiveÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (12)

- Aimez-Vous en 12 Étapes Pratiques: Un Manuel pour Améliorer l'Estime de Soi, Prendre Conscience de sa Valeur, se Débarrasser du Doute et Trouver un Bonheur VéritableD'EverandAimez-Vous en 12 Étapes Pratiques: Un Manuel pour Améliorer l'Estime de Soi, Prendre Conscience de sa Valeur, se Débarrasser du Doute et Trouver un Bonheur VéritableÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (4)

- DELF B1 - Production Orale - 2800 mots pour réussirD'EverandDELF B1 - Production Orale - 2800 mots pour réussirÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (12)

- Force Mentale et Maîtrise de la Discipline: Renforcez votre Confiance en vous pour Débloquer votre Courage et votre Résilience ! (Comprend un Manuel Pratique en 10 Étapes et 15 Puissants Exercices)D'EverandForce Mentale et Maîtrise de la Discipline: Renforcez votre Confiance en vous pour Débloquer votre Courage et votre Résilience ! (Comprend un Manuel Pratique en 10 Étapes et 15 Puissants Exercices)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (28)

- Anglais ( L’Anglais Facile a Lire ) 400 Mots Fréquents (4 Livres en 1 Super Pack): 400 mots fréquents en anglais expliqués en français avec texte bilingueD'EverandAnglais ( L’Anglais Facile a Lire ) 400 Mots Fréquents (4 Livres en 1 Super Pack): 400 mots fréquents en anglais expliqués en français avec texte bilingueÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Le fa, entre croyances et science: Pour une epistemologie des savoirs africainsD'EverandLe fa, entre croyances et science: Pour une epistemologie des savoirs africainsÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (6)

- Manipulation et Persuasion: Apprenez à influencer le comportement humain, la psychologie noire, l'hypnose, le contrôle mental et l'analyse des personnes.D'EverandManipulation et Persuasion: Apprenez à influencer le comportement humain, la psychologie noire, l'hypnose, le contrôle mental et l'analyse des personnes.Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (13)

- L'Interprétation des rêves de Sigmund Freud: Les Fiches de lecture d'UniversalisD'EverandL'Interprétation des rêves de Sigmund Freud: Les Fiches de lecture d'UniversalisPas encore d'évaluation

- Vocabulaire DELF B2 - 3000 mots pour réussirD'EverandVocabulaire DELF B2 - 3000 mots pour réussirÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (34)

- DELF B2 Production Orale - Méthode complète pour réussirD'EverandDELF B2 Production Orale - Méthode complète pour réussirÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5)

- Anglais Pour Les Nulles - Livre Anglais Français Facile A Lire: 50 dialogues facile a lire et photos de los Koalas pour apprendre anglais vocabulaireD'EverandAnglais Pour Les Nulles - Livre Anglais Français Facile A Lire: 50 dialogues facile a lire et photos de los Koalas pour apprendre anglais vocabulaireÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Réfléchissez et devenez riche: Le grand livre de l’esprit maîtreD'EverandRéfléchissez et devenez riche: Le grand livre de l’esprit maîtreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (509)

- Apprendre l’allemand - Texte parallèle - Collection drôle histoire (Français - Allemand)D'EverandApprendre l’allemand - Texte parallèle - Collection drôle histoire (Français - Allemand)Évaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2)

- Magnétisme Personnel ou Psychique: Éducation de la Pensée, développement de la Volonté, pour être Heureux, Fort, Bien Portant et réussir en tout.D'EverandMagnétisme Personnel ou Psychique: Éducation de la Pensée, développement de la Volonté, pour être Heureux, Fort, Bien Portant et réussir en tout.Évaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)