Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Gifts of Tourism

Transféré par

Ana BrunetteCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Gifts of Tourism

Transféré par

Ana BrunetteDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp.

529550, 2008 0160-7383/$ - see front matter 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Printed in Great Britain

www.elsevier.com/locate/atoures

doi:10.1016/j.annals.2008.02.002

GIFTS OF TOURISM: INSIGHTS TO CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

Jackie Clarke Oxford Brookes University, United Kingdom

Abstract: Using empirical evidence from real-life accounts of the giving, receiving and consuming of tourism and leisure products as gifts, this paper examines the phenomenon of experience gift giving behavior. Although generic gift giving has an extensive literature expanding from the 1950s, there is a gap between consumer activity in experience gift consumption and academic understanding. The study ndings show the constituent parts and processes of decision-making, gift exchange, and post-exchange, consumption and post-consumption. These concepts, whether new (for example, patterns of participation in consumption), adapted (for example, wrapping strategies) or absorbed (for example, impression management) from the gift giving literature, are drawn together as a Model of Experience Gift Giving Behavior. Keywords: gift giving, experience gifts, tourist behavior. 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. sume : Cadeaux de tourisme: des aperc Re us sur le comportement du consommateur. Cet article examine le phe nome ` ne de faire des cadeaux dexpe rience a ` partir de te moinage empirique de rive de comptes rendus de donner, de recevoir et de consommer des produits de tourisme et de loisirs en tant que cadeaux. Bien quil existe depuis les anne es 50 une litte rature e tendue au sujet ge ne rique de faire des cadeaux, il reste un e cart entre lactivite du consommateur dans la consommation des cadeaux dexpe rience et sa comprehension universitaire. Les re sultats de le tude montrent les e le ments constitutifs et les processus de la prise des de cisions, de change de cadeaux, de ce qui se passe apre ` s le change, de la consommation et de la postconsommation. Ces concepts pris de la litte rature pertinente, quils soient nouveaux (par exemple, les modes de participation a ` la consommation), adapte s (par exemple, des strate gies demballage) ou absorbe s (par exemple, la gestion de limpression), sont re unis sous forme de s: faire cadeau, cadeaux dexpe Mode ` le de Faire des Cadeaux dExpe rience. Mots-cle rience, comportement du touriste. 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

INTRODUCTION There is a discrepancy between the practice of giving, receiving and consuming gifts that are tourism and leisure experiences and an understanding of this phenomenon as evidenced in academic attention. There is historical precedence for experience gifts; travel has been exchanged as a gift, often by the elite, for many centuries. In todays developed countries, anecdotal, trade and magazine evidence (Anonymous 2005; Consumers Association 2002; Knight 2003) highlights the intangible experience as ensconced in the gift giving repertoire of many individuals. Indeed, there is even an experience

Jackie Clarke is Senior Lecturer in Marketing and Tourism at The Business School, Oxford Brookes University (Oxford, OX33 1HX United Kingdom. Email <jrclarke@brookes.ac.uk>). Informed by services marketing theory, her main research interests focus on different aspects of consumer behavior in tourism, and how such understanding underpins the theory and practice of tourism marketing across tourism sub-sectors, scales of enterprise and destinations. 529

530

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

industry of specialist companies (United Kingdom examples include Virgin Experience Days, Activity Superstore, and Experience World) that package experiences from abseiling to zoo-keeping specically for the gift buying market. In North America, tourism and leisure products a.k.a. the experience are a hot gift category for the future (Anonymous 2005:92). In reality, the designated experience industry as elucidated above (see Mintel 2001) forms only the tip of the experience gift iceberg. The vast array of tourism, hospitality and leisure providers sell products that are used by purchasers as gifts to be consumed by a third party. However, only the more enlightened of these providers are proactive in the gift giving marketplace. Curiously, this consumer activity has not been reected in academic output; doubly surprising given the maturity of gift giving literature per se. Much of the knowledge of gift giving derives from the social sciences accumulated over half-a-century (e.g. Mauss 1954), yet amongst the many sub-topics (e.g. gender, cultural context, self-gifting, dark side of giving etcetera) the intangible gift has not been singled out for observation. By default, the generic understanding of gift giving behavior is rooted in the study of physical goods, and hence the discrepancy between such consumer behavior in society and its associated academic discourse. To date, the notion of gifts and gift giving in tourism has been conned to vacation souvenirs as gifts for others (see, for example, Kim and Littrell 2001), rather than to the experience itself as a gift from one party to another to express a personal relationship. The purpose of this paper is to begin to close this gap between behavioral practice and academic understanding of tourism and leisure when conferred gift status through use of empirical evidence drawn from reallife accounts of the giving, receiving and consumption of experience gifts. It only considers experience gifts used within personal relationships; institutional or company-based gifts of tourism and leisure products are outside the scope of this study. Alongside the assessment of the constituent parts and processes, a model is proposed that expresses the blend of absorbed, adapted and new concepts to best advance the understanding of the phenomenon of experience gift giving behavior.

TOURISM AND LEISURE AS GIFTS Cheal (1987:153) denes a gift as a ritual offering that is a sign of involvement in and connectedness to another. There is nothing within this denition that precludes the experience. Indeed, the occasional experience is cited in the datasets of some gift giving studies (e.g. Durgee and Sego 2001; Mick and DeMoss 1992; Rucker, Freitas and Kangas 1996; Sherry, McGrath and Levy 1995)for example, a day at a health spa or tickets for a show on Broadway. However, any commentary is marginal to the thrust of the discussion and gives little illumination as to the nature of experience gifts or associated consumer behavior. There are two principal parties to the giving, receiving and consumption of gifts, namely the donor (singular or plural) whose activities and behavior equate to giving, and the recipient (singular or plural) whose

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

531

activities and behavior equate to receiving. This interplay ensures that any productphysical good or experiencewith conferred gift status is complex when compared to its non-gift form. All gifts reect aspects of the occasion, donor, recipient, and the existing relationship between the two parties in the exchange. Firstly, a gift will mirror the occasion for which it is chosen (Sherry 1983). Thus, a humorous gift matches the hen night, an appreciative gift Mothers Day, and a caring gift the hospital visit. A gift can fail in terms of recipient satisfaction for no other reason than it is inappropriate for the occasion it represents. The same gift will also reect characteristics of the donor in terms of motivation, resource availability, and donor self-concept. For example, donor motivation typologies (Goodwin, Smith and Spiggle 1990; Sherry 1983; Wolnbarger 1990; Wolnbarger and Yale 1993) acknowledge a darker side relating to donor power and status alongside altruistic desires for recipient satisfaction. Sherry (1983:161) refers specically to altruistic motivation, where the donor is primarily concerned with securing recipient pleasure, and to agnostic motivation, where the donor is driven by power games and calculationthe darker side. Gift selection will also reect donor resources of nance, time and personal effort (Belk 1996; Rucker et al 1996). These productive resources that echo within an individuals gifting capacity (Wooten 2000:93) transcend into notions of donor sacricea fundamental concept underpinning the gift giving literature (e.g. Hubert and Mauss 1964). The trio of resourcesnance, time, personal effortis incorporated into the symbolism of a gift, to be decoded by the recipient. A gift also resonates with the donors self-concept; research indicates that a donors ideal self-concept may even over-ride recipient characteristics in gift selection (Belk 1979; Sherry and McGrath 1989). However, a gift reects donor perception of the recipient, particularly where choice is driven by altruistic motive (Wolnbarger 1990), and successful donors are characteristically chameleon-like in behavior, blending themselves into different gift giving situations (Otnes, Lowrey and Kim 1993:231). Finally, a gift is appropriate to the nature of the relationship between donor and recipient (Cheal 1996; Ruth, Otnes and Brunel 1999), its longevity, geographical distance, and emotional intensity. Expressive gifts characterize the emotionally close relationship, and utilitarian gifts the more distant (Sherry 1983). Individual role status and role expectations as they relate to the relationship dynamic (e.g. husbandwife, godmothergodchild) also impact on gift choice. An intangible gift can reect all four aspectsoccasion, donor, recipient and relationshipas effectively as a physical good.

The Contribution of Gift Giving Models The linking of concepts to process has found expression in the models of gift giving behavior (e.g. Belk 1976; Pieters and Robben 1998), with the most comprehensive models for the decision process,

532

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

consumption and post-consumption behavior being those of Banks (1979) and Sherry (1983). Banks (1979) incorporates both donor and recipient into a four stage model of purchase, interaction (or exchange), consumption and communication. It is this gift giving model that most resembles the grand models of consumer behavior (e.g. Howard and Sheth 1969; Nicosia 1966). The Sherry (1983) model is central to many subsequent research designs (see Curasi 1999; Goodwin et al 1990; Parsons 2002; Ruth et al 1999; Wagner, Ettenson and Verrier 1990; Wolnbarger and Yale 1993). Indeed, it is described as the most comprehensive framework for understanding gift-exchange processes (Ruth et al 1999:385) evidence of its status as the premier model of gift giving. Adopting the donor-recipient perspective of the earlier Banks (1979) model, Sherrys (1983) anthropological model progresses through three stages of gestation (decision making process), prestation (gift exchange and impression management) and nally reformulation (consumption and relationship realignment). Each stage subsumes a range of gift giving concepts, yet the decision process stage (gestation) is simplied when compared to the grand models of consumer behavior, and the focus on the donor-recipient duet omits other players common to the decision making unit (DMU). Recent work by others argues for the inclusion of inuencing third parties (Lowrey, Otnes and Ruth 2004:555). From the lineage of the grand models of consumer behavior, the models addressing tourism and leisure (Mansfeld 1992; Moutinho 1987; Schmoll 1977; Woodside and King 2001; Woodside and Lysonski 1989) and other tourism behavioral research (Decrop 1999; Decrop and Snelders 2004; Hudson 1999) indicate specic features that might be expected to modify gift giving behavior when applied to gifts that are tourism and leisure products as opposed to physical goods. For instance, the emphasis on consumption (Moutinho 1987; Oppermann 1995; Thornton, Shaw and Williams 1997), including the importance of purchase-consumption systems with secondary decisions made during product usage (Woodside and King 2001:4), the recognition of group or family impact (Decrop 2005; Gitelson and Kerstetter 1994; Lawson 1991; Litvin, Xu and Kang 2004; Thornton et al 1997) wider than donor-recipient considerations, and the temporal delay between purchase and usage with its potential for post-purchase dissonance and/ or anticipation (Moutinho 1987; Parrinello 1993). Initially suggesting uniformly high levels of consumer involvement in the decision process (Banks 1979; Belk 1976), in practice, both tourism and leisure purchases (Middleton 1983) and gifts (Belk 1982) vary in consumer involvement intensity. Study Methods The research investigated how and to what extent the consumer behavioral processes evident in the giving, receiving and consumption of experience gifts differs from the generic understanding of gift giving

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

533

behavior, and whether the processes and nuances observed could be encapsulated in a model of experience gift giving behavior. The use of student informants (DeVere, Scott and Shulby 1983; Goodwin et al 1990; Otnes, Ruth and Milbourne 1994; Rucker, Freitas and Dolstra 1994; Rynning 1989) or of hypothetical design (Belk 1982; Pieters and Robben 1998; Wagner et al 1990) were rejected in favor of primary data derived from accounts of actual experience gift giving activity by informants of different ages, gender and occupation. Presented as a chronological overview of the stream of research (Gilmore and Carson 1996:23), three sequential components generated the empirical evidence, with the emphasis on the latter two components. Firstlyand the exploratory componentexpert opinion from the experience industry as expressed by Marketing Directors of leading experience companies in the United Kingdom and captured through semi-structured telephone interviews. Secondly, consumer recollections of real-life giving, receiving and consumption of experience gifts as expressed by donors or recipients and captured through depth interviews, yielding 52 experience gift giving cases. Thirdly, consumer recollections of a ight experience gift as expressed by 137 recipients post-use and on-site at four airelds of a specialist aviation experience company using a self-completion written instrument. Interviews. The telephone interviews extracted expert opinion from the experience industry to establish the context for the ensuing research. An exploratory phase, four experts (Informants A, B, C and D) from different branded experience companies outlined the patterns of experience gift consumption as exhibited in the United Kingdom, and provided commentary on the comparison between United Kingdom market behavior and other developed countries. For example, Informant C reiterated the strength of the experience gift giving trend, population down-aging driving people in their fties and sixties to an absolute change in behavior, and believed that the United Kingdom had the most developed experience industry of any country (the United States being highlighted as more fragmented). This context-setting work helped orientate the researcher to the experience industry and to the experience gift buying public. The depth interviews with consumer informants formed the backbone of the research, enabling individuals to express their own constructs of experience gift giving reality. Ten informants were recruited through an informant-controlled postcard system so that informants were previously not known to the researcher. These postage-paid postcards were printed with the researchers contact details and space for the potential informants preferred contact details (landline telephone, mobile telephone, e-mail address, business or home address); the potential informant returned the postcard thereby allowing the researcher to make contact by the method indicated. The sole selection criterion was that the informant had either given or received one or more experience gifts during the preceding two years. Informants completed a proforma sheet recording categorical data and informant condence in general gift giving skills prior to the interviewinformants were from different age, occupation and gender categories.

534

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

The interviews commenced with a grand tour question (as used in gift giving behavior, for example, by Ruth et al 1999:387) recalling a specic case of experience gift exchange, then loosely tracked the Sherry (1983) stages of gestation, prestation and reformulation in eliciting case detail. Interviews concluded with an invitation for any incidents of negative experience gift exchange to provide contrasting data drawn from a different form of probing. The phraseology and exact vocabulary of each informant was captured through tape recording and subsequent transcription. Data was analyzed using a modied constant comparison method (Belk and Coon 1993; Wooten 2000), with labels emerging from gift giving theory (e.g. surprise, donor sacrice, wrapping strategy, impression management, gift rejection), informant vocabulary (e.g. dust collectors, project manager, follow me, double presents), and data interpretation (e.g. accomplice, plotters, discussers, post-exchange planning, recipient sacrice, decoy strategy, consumption participation). The resulting themes were checked back against the original discrete case story and against patterns of negative incidents, with several modications enacted through this process (e.g. concept of dismay in opposition to delight). Of the 52 experiences recounted, 29 involved the informant as donor and 23 as recipient. All incidents recounted were demonstrative of close relationships (Sherry 1983) or of special people (Informant C) dened as a close circle of family and friends (Informant C). No cases of experience gift exchange in non-signicant relationships (or Joys 2001:245 Hi/Bye friends) were evident in this dataset. Written Instrument. The recipient informants completing the written instrument did so in the physical surroundings of the experience consumed and in the immediate aftermath of its consumption. A specialist experience company operating ights on historic aircraft (e.g. Tiger Moths, Hurricanes) managed the written instrument on behalf of the researcher at four airelds across the United Kingdom (South Yorkshire, Manchester, Leicestershire, and Surrey). Consumers who had been given their ight experience as a gift were invited by ground crew after their ight to complete a written instrument. This focused on the gift occasion, participant relationships, and post-exchange and consumption behavior, which had emerged as important aspects of experience gift giving behavior from the depth interviews. A total of 137 recipient accounts were returned for analysis. The categorical data was described using SPSSpc, and the text was treated to the same process as the depth interviews, with emerging themes and patterns compared against depth interview ndings. These ight gift recipients were mostly male, and came from across the age and occupation spectrums.

Study Findings The ndings of the study are structured into decision-making, exchange, and post-exchange/consumption/post-consumption. Each section examines how aspects of experience gift giving behavior differ in either substance or nuance from the generic understanding of gift

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

535

giving behavior. Examples of empirical evidence in the form of verbatim quotes are woven into the text and denoted by italics and single quotation marks. Additionally, more substantial vignettes are indented and sourced to the relevant informant. In drawing together the disparate conceptsabsorbed, adapted and newemerging from the analysis, a Model of Experience Gift Giving Behavior is presented and its credentials discussed. The Decision-Making Process The respective inuences of occasion, donor, and relationship characteristics are much as represented within the generic gift giving literature. For example, occasion often equating to problem recognition donor realization that a gift is requiredwhilst donor motivation exhibited both agnostic (I really enjoy this, now you can try it too) and altruistic (it means more to them than it would do to me) traits. However, the reorientation of recipient lifestyles (such as simplifying and de-cluttering the home environment) and the existence of the difcult recipient who communicate very specic gift requirements or reject physical gifts as dust collectors act as trigger mechanisms to the idea of an experience as the solution to a gifting problem. The intangibility of the experience makes it amenable to on-line information searches and to the evaluation of alternative experiences with regard to features and prices. The internet was used for both

nding an hotel, seeing who was on at the jazz club, booking London Eye tickets, nding out when shark feeding is on at the aquarium (Female, 2635, donorLondon experience),

in other words, the accumulation of product detail, and for examining

a couple of sites and some of them were of comparable price but the time on the track it was a number of laps round the track and one was shorter than the other something might be (US$20) cheaper but it could then lessen the experience (Female, 2635, donorFormula One rally driving),

or the evaluation of competing experiences with regard to product features, price and value for money. Many experience gifts were planned as surprises, and an extended Decision Making Unit (DMU) emerged incorporating the new role of an accomplice someone close to the recipient (their nearest and dearest) who provides additional advice as to the t of the proposed experience to the recipients lifestyle and schedule whilst shielding the recipient from any knowledge of the intended gift. The role carries connotations of subterfuge, of secrecy, of plotting. Witness the activities of accomplice Michael (husband of recipient) as described by the donor,

he said Yes, shes got a bee in her bonnet about it, so I think it would be a good gift and I said But we need to keep it a surprise, can you put her off? Or something like that, because what I didnt want her to do was book it herself or something like that. So that worked quite well he dampened down the expectations and the idea a bit and I meanwhile booked it on the web. Michael knew all the

536

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

details, so he was booking ferries in time to t in with this trip to New York (Female, 3645, donorWeekend in New York).

The end decision will result in one of three types of experience giftsa purchased commercial experience (for example, tank driving), a modied commercial experience (for example, Tiger moth ight plus dinner afterwards), or a hand-crafted created experience (for example, a London experience of the London Eye, museum visits, lunch and evening cinema). Table 1 gives further examples of experience gifts for each category drawn from the dataset. The commercial experience may be purchased from an experience company or from a leisure, tourism or hospitality provider. Conversely, the hand-crafted created experience is concocted by the donor from any number of purchased and/or non-commercial elements into a unique experience tailored specically to the recipient. Any or all of the three elements of planning, creation and purchase follow the decision to give a specic experience. Finance, time and personal effort are expended as donor sacrice to be later decoded by the recipient; time and effort in organizing the experience may be valued by the recipient above the nancial outlay or easy money ticket. As expressed by one informant,

I think Id rather just do something. I think it shows thought and care and Im prepared to put the time in to think about it (Female, 2635, donor).

A group of donors may enlist a project manager to co-ordinate activities, a further extension of the traditional DMU, and a label used by a donor to describe her particular gift giving case,

Thats for my Dad, and its really my sister, my Mum and myself who are putting it all together, but Im the one in charge of sorting it out project manager if you like (Female, 2635, donorLondon experience. Researchers emphasis).

Table 1. Examples of Purchased, Modied, and Created Experience Gifts

Purchased Tiger moth ight Half-day off-road driving Venice trip EuroDisney trip Modied Tiger moth ight & BBQ Single seater racing & lunch Thames boat trip & dinner Kayaking trip & B & B accommodation Spa day & dinner Hurricane ight & pub lunch Created Blenheim Palace experience: palace visit & picnic London experience: West End show & lunch & Harvey Nichols shopping London experience: London Eye & museums & lunch & cinema London experience: London Eye & Ronnie Scotts & aquarium & accommodation London experience: London Eye & IMAX cinema Camping barn trip: accommodation & activities & meals

Wood turning course Hot air balloon ight

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

537

A different perspective of the project manager role is recounted for a gift of a hot air balloon ight,

My sister and brother-in-law are very good at organizing things and they get on the phone and get things sorted theyve no more time than I have really but they . . .anyway, it was nice to sit back and let them get it all sorted out (Male, 5665, donorHot air balloon ight).

The behavior of donors from problem recognition through to decision could be summarized through a dichotomy of decision styles; the plotters and the discussers. In actuality, this dichotomy might be better expressed as a continuum, with the plotters and discussers at opposing ends, but the variations are better understood in relation to the purest forms of procurement behavior. The plotters plan covertly, using the language of conspiracy (plotting, on the quiet, sneaky and surreptious). Such donors will make use of an accomplice, should the person closest to the recipient not be in the donor group. The ultimate aim is to maximize recipient surprise at the point of gift exchange. Within Western cultures, the achievement of recipient (positive) surprise is one of the dimensions of the perfect gift (Belk 1996), which partially explains its emphasis in plotters behavior. In addition, donors appear to derive huge enjoyment from sorting it out in secret, with such activity bringing us all together really. In contrast, the discussers plan overtly with the recipient; for the recipient of a Venice trip, this was something we had talked about for ages. The advantage for the discussers is that the risk both in nancial and psychological terms is very low, as the recipient has direct input into gift planning. There may be no surprise, but discussers minimize risk. In its purest form, it may be that discussers are outnumbered by the plotters; evidence from the historic ight gifts suggested that whilst plotters formed about 90% of cases, discussers formed only 2%. The remainder confessed to hinting to the donor. Thus, the continuum may be the more accurate reection of decision styles. Firstly, there are the hinters who have expressed a distinct desire to do something to the donor. Secondly, donors themselves may engage in a form of sleuthing (Otnes et al 1993:232), quizzing the recipient and possibly losing the element of surprise (although the recipient may engage in impression management at the point of exchange so that donor feelings are not jeopardized). Thirdly, donors may maintain a sort of 80% secrecy, planning along a timeframe as a plotter, but having to reveal the experience to the recipient ahead of exchange in order to nalize arrangements. The two interceding factors appear to be securing time in the recipients diary to undertake the experience, and nancial agreement where spend was not inconsiderable; they had a joint account and she was bound to notice if he took (US$6,000) out. . .before it was too late to turn back, he checked it out with her. Finally, there are the breakdowns in service delivery that can mar any service encounter, and certainly a surprise experience gift. For example, a New York trip was undertaken by plotters, but the surprise element was lost when the ticketing agent posted ight details against instruction direct to the

538

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

recipient rather than to the donor. The remaining planning was undertaken in discussion mode, albeit with a tickled pink recipient. Regardless of decision style, donors are likely to feel post purchase anxiety and / or positive anticipation, even excitement prior to gift exchange. Donors referred to the fun of anticipating what his reactions are, and one donor was described as very pleased with himself and as having bounced in on his return from an experience gift purchase. In summary, the study ndings for the decision-making process highlighted a mix of absorbed, adapted and new concepts in experience gift giving behavior. Broadly speaking, occasion, donor characteristics, relationship characteristics, and donor post-purchase anxiety / anticipation might be categorized as concepts absorbed from generic gift giving behavior. However, recipient characteristics demonstrated the inuence of changing lifestyle and the rise of the difcult recipient. Information searches and product comparisons were often conducted on-line, facilitated by the service characteristic of intangibility. And donor sacrice showed scope for a shift in resource emphasis to time and personal effort spent in planning the experience. These three are categorized as concepts adapted from generic gift giving behavior; there is a change in emphasis to better suit the experience gift situation. Finally, the accomplice, the project manager, and the decision style of plotters and discussers are new concepts to emerge from the study ndings. Arguably (because such a trio is not noted in the generic literature), the possible experience gift product types of purchased, modied and donor-created might also fall in the new concept category (although a case can be made for adaptation as, for example, hand-made gifts such as home-knitted sweaters are a classic physical goods gift). The Exchange The experience is given to the recipient the donor may or may not be present at the moment of exchange. Evidence suggested that social and physical settings, ritual and artifacts, and impression management by the recipient at this stage deviate little from generic expectations. Certainly, experiences were largely successful in their ability to surprise the recipient. Many of the experiences within this dataset had been assigned the status of the big one, or the gift that the donor had invested with the greatest meaning, and this may have swayed the social and physical settings towards the more intimate. For example, one recipient stated that

it would have somehow lost its signicance if there had been other people around who didnt know about the particular meaning of this gift (Female, 4655, recipientVenice trip).

However, this leaning to the private exchange was not universal. Experience gifts did appear to differ from generic gift giving theory (see Hendry 1993) on the matter of wrapping strategies. Underpinning the wrapping strategies for the experience gift is the donor dilemma of

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

539

presenting a gift which is intangible. A physical gift has a tactile presence that lends itself to wrapping; an experience has no substance it exists as a promise of engagement in, or access to, an activity at a future time. For the experience gift, ve wrapping strategies emerged from the data analysis. The rst wrapping strategy is the special card/ envelope executed in a number of ways from envelope color e.g. gold to a written token of the gift;

she put the conrmation from the gliding club into a birthday card so when I opened the card the thing was in there (Male, 4655, recipientGlider lesson).

The weakness of this wrapping strategy is that it offers only supercial disguise, having instant associations with money or vouchers. The second wrapping strategy is that of the box. As a tangible item associated with protecting physical goods, this serves to deect the recipients attention until the card/voucher is revealed, thus prolonging the surprise. Box choice may be elaboratecream and aubergine embossed boxto ag experience quality and to facilitate post-exchange public display, or big to tangibly express the magnitude of the gift e.g. commercial experience companys tank driving experience. The third wrapping strategy makes use of a physical surrogate. A physical item directly associated with the experience is wrapped, such as golf balls to represent golng lessons, or a teddy bear in ying jacket and goggles for a Tiger Moth ight. The difference from strategy ve lies with the innate symbolism. Fourthly, a Russian-doll strategy is when a physical item directly associated with the experience performs the task of replacement wrapping paper around a card/envelope. This physical item itself may be wrapped or placed in a box, thus extending the revelation, converting it from wrapped gift to physical gift and nally to experience. For example,

I happened to nd some socks in Tesco with Footynut the little cartoon on the side so I wrapped this little season ticket holder inside the socks so he thought hed just got a pair of socks, you know silly socks for Christmas so there was a bit more to it (Female, 4655, donorFootball season ticket).

Use of tangible co-ordinates forms the nal wrapping strategy. A popular supporting strategy when gift exchange is verbal, tangible co-ordinates are material goods that accessorize the experience and provide physicality e.g. fur hat for New York winter trip, or a nice photo album for a London experience. When the experience is to commence immediately upon exchange, a follow me strategy with the gift components for experiences (activities, locations, and co-participants) revealed in a piecemeal fashion is an additional option for the donor.

All he said to me was I want you to be ready to go out at 9 oclock on the Friday morning, and I said What do I need to wear?, because I didnt want to wear inappropriate clothes, and he said No, whatever you want. And I said Casual? and he said Yep, whatever. Typical. What he wears is always a clue. If hed been in a suit I might have needed to smarten myself up. My

540

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

sister-in-law and mother-in-law came round, and I didnt know they were coming. And I still didnt know where we were going and we had a picnic hamper, but I couldnt work out what it was until they got to the boat yard around Jericho (Female, 4655, recipientThames boat trip).

The follow me strategy (dened by an informant as do what I say) integrates immediate consumption with the element of gift surprise, and in the vignette above involved all three components of activities, location, and co-participants. Other cases described involved all three, two, or just one. For example, a male recipient of a EuroDisney trip to France knew he would be going with his partner but only suspected it was EuroDisney when we started heading towards Paris. A Tiger Moth ight recipient knew about watching some historic airplanes ying at a local aireld but once there had a shock on being told youre going up in the next ight! In summary, the study ndings for the exchange of experience gifts suggested that the social and physical setting, ritual and artifacts used, and impression management were largely absorbed from the generic gift giving behavior literature (although there was some indication of donors favoring private settings for exchange and for perceiving the experience gift as the most meaningful). The ve wrapping strategies might be categorized as adapted from the mainstream theory as the options provided possible solutions for the exchange of an intangible gift i.e. one that, in practice, isnt even physically present at the point of exchange. The follow me strategy, a new concept generated by the study ndings, enabled immediate consumption upon exchange to be combined with gift surprise. Post-exchange/Consumption/Post-consumption In contrast to immediate consumption, experiences to be consumed at a future date often require post-exchange planning. This may involve ongoing donor effort, but it is also likely to entail recipient sacrice of all or any of the three productive resources of nance, time and personal effort. Of the historic ight experience gifts, 29% of recipients claimed to have organized the booking, 15% organized the group, 54% organized the transport, and 30% the meals for the day. A female donor of a gourmet hotel stay described how the recipients (her parents) had

gone online and looked at all the rooms and decided when they want to go and which room they want to go in and they phoned up the hotel and booked it themselves (Female, 2635, donorLe Manoir experience).

However, if the recipients perception of their own sacrice outweighs their perception of donor sacrice, then the appreciation and meaning of the gift may be diminished. The hassle of paying for additional co-participants, travel expenses, food and incidental costs and cancellation of commitments may combine to make the experience an unwanted burden to the recipient. Gift rejection is apparent as for physical goodsdismay in opposition to the more typical delight.

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

541

For example, approximately 1% of commercial experience gifts are swapped through the experience company system (Informant A). One of the historic ights was an unwanted birthday gift for my father and hence redistributed to the son. A vivid portrayal of a rejected white water rafting trip emphasized that

we have very, really busy lifestyles so the children all have commitments at weekends and our holidays are booked for ages in advance. The places you could go to do white water rafting in this country are not Oxfordshire Scotland, Snowdonia, the Lake District, and so the opportunity for us to go up to the Lake District to use one gift token well, forget it (Female, 3645, recipientWhite water rafting).

Post-exchange anxiety and anticipation are likely emotional states for both donor and recipient. If suspense is desired, the donor may seek to develop recipient anticipation through use of a decoy strategy. The recipient is given lists or hints of things to bring for the experience with most of the items chosen for camouage. One recipient was temporarily deceived into believing she was going bog snorkeling in Wales; another on instruction took a tent and passport and snorkel on the back of his motorbike for a surprise trip to Glastonbury UK, making the passport and snorkel redundant. As for the follow-me strategy, the decoy strategy builds in an extended element of surprise. Recipient sacrice is also evident for the immediate consumption of experience gifts, although (assuming the gift has been well designed by the donor) time is the required resource. During consumption, the donor may use suspense in the form of a follow-me strategy to gradually reveal the experience activities, locations, and co-participants. Each experience gift, whether involving immediate or delayed consumption, will incorporate a travel element to and from one or more locations such is the nature of simultaneous production and consumption using the producers premises. There are exceptions to this type of experience gift; for example, a massage could be taken at the recipients home. However, such experience gifts did not appear prevalent; there were none in the dataset. In addition, the experience gift could unfold as a series of repeated events, with a course of lessons serving as an example. The strength of donor sacrice during consumption is best illustrated where donors choose to spend time with the recipient. The evidence indicated four types of consumption participation, the rst two of which demonstrate such donor sharing with the recipient. The rst consumption pattern is that of the donor as participant. The donor is immersed in the activity, taking part alongside the recipient; we do it together. This integration of complete sharing encourages deeper bonding in the relationship, whilst allowing the donor to retain some control over external incidents such that might befall any realtime service product. However, donors may elect not to participate in the experience because nancial resources are limited or because lifestyle, lifestage, geographical distance, or health issues make joint participation an unattractive proposition. The second consumption pattern involves the donor as spectator. Here, the donor accompanies the recipient but elects to watch the

542

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

central experience. A form of sharing, the donor still retains some control over the proceedings. Commercial experience companies understand the importance of binding spectators into the experience e.g. before and after the event. Of the historic ight gifts, 77% involved the donor as spectator. Donors may still participate in other components of the total experience e.g. travel, meals, add-on activities. The third is that of signicant other(s). The donor is not present at experience consumption. Instead, the recipient carries out the experience with invited companions. As one donor explained

I did it because at that time her daughter was living and working in London and she could go and visit her in London and so it was a nice trip they could do together (Female, 3645, donorSpa day).

Typically, sharing with signicant others arises when there is a marked difference in donor-recipient age (young teenagers like to do this kind of thing with a mate), lifestyle, physical ability, or geographic residence (as in the vignette of the Spa day). The fourth consumption pattern is that of co-consumers. The recipient is without donor or known companions for the duration of the experience. The experience is made or marred by the behavior of co-consumers, previously unknown to the recipient. One recipient of a Spa day described herself as lucky enough as she met a woman with whom she arranged to have lunch. Relying on co-consumers is the riskiest type of participation, and appears to raise recipient post-exchange anxiety; for example, one informant reecting on the possibility of being given a trip to a Spa reported

Id think What? Am I supposed to go on my own or something? Id probably feel a little bit, oh, anxious. Because I do get a bit like that (Female, 2635).

The conferring of additional gifts during experience consumption is not uncommon. It is notable that experiences involving delayed consumption often trigger extra gifts, double presentswhether experiences or physical goodsthat are exchanged at the time of consumption. The nal components of post-consumption evaluation, reciprocity and role reversal are in line with generic thinking. However, two plausible points of possible emphasis emerge. Firstly, that the recipients of experiences absorb the idea of such gifts into their general gift repertoire, not necessarily for reciprocity with that particular donor, but for other members of their gift giving network. This bodes well for the expansion of experience gifts in the marketplace, the hot gift category (Anonymous 2005:92) noted in the introduction to the paper. Secondly, that impression management for the recipient is important post-consumption too, as donors appear to seek a second dose of feedback, this time with the focus on experience performance. The study ndings for the post-exchange, consumption and postconsumption of experience gifts suggested that standard gift giving concepts such as post-consumption evaluation, reciprocity, role reversal and gift rejection are also evident in experience gift giving behavior. There is a slight emphasis on impression management in that, here, it is about gift performance, rather than its previous incarnation upon

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

543

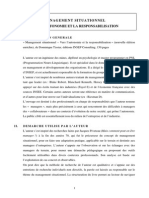

gift exchange. Donor sacrice has an adapted feel, for there is an emphasis on donor time and personal effort, which is demonstrated through post-exchange planning and through the participation patterns involving the donor. Recipient sacrice, planned or otherwise, comes to the fore as a new concept, as do the decoy strategy, consumption patterns of participation, and the notion of double presents (whether add-on experiences or physical goods) as a result of the time lag between exchange and eventual gift consumption. A Model of Experience Gift Giving Behavior The consumer behavior observed in the decision process, exchange, and consumption of experience gifts can be encapsulated in a Model of Experience Gift Giving Behavior (Figure 1). It draws together the

Occasion Relationship Internal External Purchased Modified Created Donor sacrifice Post-purchase/creation anxiety/anticipation Social & physical setting Ritual & artefacts

Information search Decision Planning, creation & purchase Problem recognition Evaluation of alternatives

Donor - resources motivation Recipient DMU accomplice Donor resources Decision style plotters / discussers DMU accomplice - project manager

Exchange

Wrapping strategies (5) Impression management

Post-exchange anxiety Immediate /anticipation Post-exchange Decoy strategy planning Recipient sacrifice Donor sacrifice Exchange, Rejection return, redistribute Consumption Delayed Double presents - experiences - physical goods

Home location Travel Travel Experience location

Recipient sacrifice Donor sacrifice Follow me strategy Patterns of participation - donor as participant - donor as spectator - significant other(s) - co-consumers Impression management

Relationship realignment Extension of recipient gift repertoire

Series

Post-consumption evaluation Role reversal Reciprocity

Figure 1. A Model of Experience Gift Giving Behavior

544

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

constituent parts and processes from the study ndings. The strength of the model lies with its grounding in empirical evidence and with its versatility in encompassing a number of key dimensions in experience gift giving behavior. Firstly, it is exible across experience gift types, absorbing purchased experiences, modied experiences and donorcreated experiences, whilst acknowledging the true experience industry as wider than the commercial specialists portrayed by Mintel (2001). Secondly, it allows for different decision styles (plotters and discussers), and recognizes the importance of an extended DMU for experience gift decisions beyond the traditional donor-recipient focus e.g. the roles of the accomplice and the project manager. Thirdly, it is not limited in consumption or usage pattern; both immediate and delayed consumption experience gifts are integrated into the model. Fourthly and similarly, the model caters both for the single experience gift e.g. theatre trip, and the series experience gift e.g. golf lessons. Fifthly, it conveys a strong avor of family and group inuence and involvement, as recognized also in the consumption of non-gift tourism and leisure products e.g. extended DMU, decision styles, consumption patterns of participation. The model successfully blends the generic gift giving concepts, the adapted concepts that deliver particular emphasis, and the new concepts that also emerged from the empirical evidence. In doing so, it develops the understanding of experience gift giving as a modernday phenomenon, thus helping to close the gap between real world activity and academic knowledge. As an introduction to reading the Model of Experience Gift Giving Behavior, it is useful to note that the stages read in temporal sequence down the centre of the page from problem recognition through to reciprocity and role reversal, and that, unlike the Banks (1979) or Sherry (1983) process models, the model does not divide on a donor recipient basis. Flanking the ow diagram section of the model are the concepts and behaviors associated with each specic stage. For example, the opening stage of problem recognition is anked by the characteristics of the occasion, relationship, donor, and recipient, whilst post-exchange planning is anked on the left by post-exchange anxiety/anticipation, decoy strategy, recipient sacrice, and donor sacrice. The stage of exchange is separated out by two dotted lines; the accompanying explanation is presented under the exchange in the study ndings text. Above exchange is the zone of the decisionmaking process, embracing problem recognition through to planning, creation and purchase. Below exchange is the zone of post-exchange, consumption and post-consumption, embracing postexchange planning and immediate consumption through to reciprocity and role reversal. As with exchange, the reader should refer to the matching study ndings section in the text for fuller detail. On initial perusal of the model, one might expect the donor to dominate the decision-making process, both donor and recipient to be equally engaged in the exchange, and the recipient to dominate post-exchange, consumption and post-consumption. However, the reality is more subtle and with plenty of scope for variety between cases.

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

545

For example, whether the decision style is one of plotting or discussing will affect the role of the recipient in the decision-making process. Conversely, the donor can be very much involved with experience consumption if they choose to actively participate alongside the recipient. As before, the study ndings sections illuminate these intricacies of donor and recipient interaction and inuence. The stage of consumption has been boxed off within the model as it holds and relates a number of components. Immediate consumption takes place straight after exchange, so there is no signicant lapse of time. It is shown on the model as close to the exchange line. However, delayed consumption takes place after post-exchange planning so there is a time lapse; boxing off allows these two types of experience consumption to keep their association both with each other in spite of the temporal differences and with the remaining boxed off components. The circle of home location, outward travel, experience location, and return travel breaks down experience consumption into constituent parts that reect the typical spatial dimension of an experience giftregardless of whether it is designed for immediate or delayed consumption. At the bottom left hand corner of the consumption box are two additional corners marked series, drawn to give a 3D effect and to reect the fact that an individual experience can be one of a series of experiences that make up the gift, such as a course of lessons in a special interest, annual membership of an historic houses charity, or season ticket for a football club. There are three biases to the model that merit recognition. The rst is its geographic bias by dint of its reliance on United Kingdom data. Within the generic gift giving literature, there are indications that some constructs may be culturally bound. For example, the value assigned to donor sacrice of time and personal effort, and to the appreciation of surprise as a gift attribute, may play out differently in Eastern cultures (Belk 1996; Ertimur and Sandikci 2005; Joy 2001; Rucker et al, 1996). This said, Rucker et als (1996) emphasis in Asian cultures on the importance of being with close friends and relatives suggests that experiences might, or could in the future, feature strongly in gift giving repertoires. The model needs testing in other cultural contexts to gauge its global relevance. Indeed, research of experience gifts in other cultures and cross-cultural studies would contribute to a fuller understanding of experience gift giving behavior and would mirror the ongoing development of generic gift giving through the cultural lens (see, for example, Gehrt and Shim 2002; Lotz, Soyeon and Gehrt 2003; Minowa and Gould 1999; Mortelmans and Damen 2001). Secondly, the experience exchanges in the dataset informing the model comprised cases where donors and recipients were in an emotionally close or reasonably close relationshipthe special people of Informant C. Anecdotal information relayed that experience gifts do occur in less signicant relationships e.g. parent to childs teacher. Such exchanges may be under-represented here by nature of memorabilityinformants may have self-selected for interview on the basis of the big one that they were happy to talk about, and by nature of giftthe historic ight experience was an expensive gift that screened

546

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

out less meaningful relationships. This bias ties in with the third bias of monetary value, for most of the cases in the dataset (though not exclusively so) were of high monetary value. Yet some experience gifts involve small nancial outlay e.g. cinema tickets. Therefore, additional research focusing on more emotionally distant relationships and on experience gifts of low monetary value would allow useful cross-examination of the model. CONCLUSION This research is believed to be the rst focused study of the consumer behavior associated with tourism and leisure products that are assigned gift status. It sought to explore how the concepts and processes evident in selecting, exchanging and consuming experience gifts might vary in either fact or emphasis from the generic knowledge of gift giving behavior embedded in the social science literature, and whether these ndings could coalesce as a model to better understand experience gift giving behavior. Empirical evidence was derived from the informant accounts of 189 real cases of experience gift giving drawn from depth interviews and a written instrument; the dataset had a United Kingdom orientation and emphasized the closeness of relationships together with the high monetary value of experience gifts. The experience gift itself offers much scope and exibility to the imagination of the donor, for, although they can be purchased as convenience packages from the experience industry, they may also be handcrafted by the donor using a mix of services straight from the suppliers. Thus the individuality of a particular gift and its t to the foibles of the intended recipient make it uniqueenhanced of course by the inherent variability in experiences or services. The proposed Model of Experience Gift Giving Behavior is based around the three broad stages of the decision-making process, the exchange, and post-exchange/consumption/post-consumption, and successfully combines the generic gift giving concepts, the adaptations, and the new concepts all emerging from the empirical evidence on experience gifts. The model allows for immediate and delayed consumption, for one-off and series experiences, and for commercially formulated, modied and handcrafted experiences; in this, it encompasses a range of possible experience gift choices. As suggested in the paper, cross-cultural studies of experience gift giving behavior that explored the transferability of both the constructs and the Model of Experience Gift Giving Behavior would contribute to the further understanding of this phenomenon. Focused research on the three types of experience giftspurchased, modied and createdwould bring additional detail to the discussion. Other avenues for future research questions include those focusing on individual gift giving conceptsfor example, donor motivation, recipient sacrice, exchange rituals and artifactsas expressed in experience gift giving behavior, and the specic research streams on gift giving sub-topics as previously examined in generic gift giving researchfor example, gender, self-gifting, or the dark side of giving. Tangentially, experience

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

547

gift giving offers insights to the shared consumption of tourism and leisure with signicant others, and to the meaning of quality time in a time pressured societyrich hunting grounds for social science. Furthermore, the research poses questions as to the role of the experience gift in the formation, development, and maintenance of personal relationships in the twenty-rst century. Moving away from personal relationships, an examination of the use of experience gifts in a corporate contextfor example, for employee and intermediary motivation or employee retirementmight also have research appeal. Through offering insights and a model to conceptualize an important phenomenon concerning tourism and leisure in todays wealthy Western societies, this paper marks experience gifts as worthy of academic recognition and greater understanding, opening the way for debate and discussion on this hitherto unexposed topic.

REFERENCES

Anonymous 2005 New Survey Finds Gift Giving on the Rise. Souvenirs, Gifts, & Novelties 44:92111. Banks, S. 1979 Gift Giving: a Review and Interactive Paradigm. Advances in Consumer Research 6:319324. Belk, R. 1976 Its the Thought that Counts: a Signed Digraph Analysis of Gift Giving. Journal of Consumer Research 3(3):155162. 1979 Gift Giving Behavior. In Research in Marketing Volume Two, J. Sheth, ed., pp. 95126. Greenwich CT: JAI Press. 1982 Effects of Gift-Giving Involvement on Gift Selection Strategies. Advances in Consumer Research 9:408412. 1996 The Perfect Gift. In Gift Giving. A Research Anthology, C. Otnes and R. Beltramini, eds., pp. 5984. Bowling Green: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. Belk, R., and G. Coon 1993 Gift Giving as Agapic Love: an Alternative to the Exchange Paradigm Based on Dating Experiences. Journal of Consumer Research 20:393417. Cheal, D. 1987 Showing Them You Love Them: Gift Giving and the Dialectic of Intimacy. Sociological Review 35(1):150169. 1996 Gifts in Contemporary North America. In Gift Giving. A Research Anthology, C. Otnes and R. Beltramini, eds., pp. 8598. Bowling Green: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. Consumers Association 2002 On the First Day of Christmas . . . Which? Magazine December:3436. Curasi, C. 1999 In Hope of an Enduring Gift: the Intergenerational Transfer of Cherished Possessions; a Special Case of Gift Giving. Advances in Consumer Research 26:125132. Decrop, A. 1999 Personal Aspects of Vacationers Decision Making Processes: an Interpretivist Approach. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 8(4):5968. 2005 Group Processes in Vacation Decision-Making. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 18(4):2336. Decrop, A., and D. Snelders 2004 Planning the Summer Vacation. An Adaptable Process. Annals of Tourism Research 31:10081030.

548

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

DeVere, S., C. Scott, and W. Shulby 1983 Consumer Perceptions of Gift-Giving Occasions: Attribute Saliency and Structure. Advances in Consumer Research 10:185190. Durgee, J., and T. Sego 2001 Gift Giving as a Metaphor for Understanding New Products that Delight. Advances in Consumer Research 28:6469. Ertimur, B., and O. Sandikci 2005 Giving Gold Jewelry and Coins as Gifts: the Interplay of Utilitarianism and Symbolism. Advances in Consumer Research 32:322327. Gehrt, K., and S. Shim 2002 Situational Inuence in the International Marketplace: an Examination of Japanese Gift-Giving. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice 10(1):11 22. Gilmore, A., and D. Carson 1996 Interactive Qualitative Methods in a Services Context. Marketing Intelligence and Planning 14(6):2126. Goodwin, C., K. Smith, and S. Spiggle 1990 Gift Giving: Consumer Motivation and the Gift Purchase Process. Advances in Consumer Research 17:690698. Hendry, J. 1993 Wrapping Culture. Politeness, Presentation and Power in Japan. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Howard, J., and J. Sheth 1969 The Theory of Buyer Behavior. New York: Wiley. Hubert, H., and M. Mauss 1964 Sacrice: Its Nature and Function. London: Cohen and West. Hudson, S. 1999 Consumer Behavior Related to Tourism. In Consumer Behavior in Travel and Tourism, A. Pizam and Y. Mansfeld, eds., pp. 768. Oxford: Haworth Hospitality Press. Gitelson, R., and D. Kerstetter 1994 The Inuence of Friends and Relatives in Travel Decision Making. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 3(3):5968. Joy, A. 2001 Gift Giving in Hong Kong and the Continuum of Social Ties. Journal of Consumer Research 28:239256. Kim, S., and M. Littrell 2001 Souvenir buying intentions for self versus others. Annals of Tourism Research 28:638657. Knight, I. 2003 The Best Presents are those that are Emotionally Resonant. The Sunday Times Style Magazine October 26th:1617. Lawson, R. 1991 Patterns of Tourist Expenditure and Types of Vacation Across the Family Life Cycle. Journal of Travel Research 29(4):1218. Litvin, S., G. Xu, and S. Kang 2004 Spousal Vacation-Buying Decision Making Revisited Across Time and Place. Journal of Travel Research 43(2):193198. Lotz, S., S. Soyeon, and K. Gehrt 2003 A Study of Japanese Consumers Cognitive Hierarchies in Formal and Informal Gift-Giving Situations. Psychology and Marketing 20(1):5985. Lowrey, T., C. Otnes, and J. Ruth 2004 Social Inuences on Dyadic Giving Over Time: A Taxonomy from the Givers Perspective. Journal of Consumer Research 30:547558. Manseld, Y. 1992 From Motivation to Actual Travel. Annals of Tourism Research 19:399419. Mauss, M. 1954 The Gift. Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. London: Cohen and West.

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

549

Mick, D., and M. DeMoss 1992 Further Findings on Self-Gifts: Products, Qualities and Socioeconomic Correlates. Advances in Consumer Research 19:140146. Middleton, V. 1983 Product Marketing Goods and Services Compared. The Quarterly Review of Marketing Summer:110. Minowa, Y., and S. Gould 1999 Love my Gift, Love me or is it Love me, Love my Gift: A Study of the Cultural Construction of Romantic Gift Giving Among Japanese Couples. Advances in Consumer Research 26:119124. Mintel 2001 Activity Days Out. London: Mintel Leisure Intelligence. Mortelmans, D., and S. Damen 2001 Attitudes on Commercialisation and Anti-Commercial Reactions on GiftGiving Occasions in Belgium. Journal of Consumer Behavior 1(2):156173. Moutinho, L. 1987 Consumer Behavior in Tourism. European Journal of Marketing 21:544. Nicosia, F. 1966 Consumer Decision Processes: Marketing and Advertising. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall. Oppermann, M. 1995 A Model of Travel Itineraries. Journal of Travel Research 33(4):5761. Otnes, C., T. Lowrey, and C. Kim 1993 Gift Selection for Easy and Difcult Recipients: a Social Roles Interpretation. Journal of Consumer Research 20:229244. Otnes, C., J. Ruth, and C. Milbourne 1994 The Pleasure and Pain of Being Close: Mens Mixed Feelings about Participation in Valentines Day Gift Exchange. Advances in Consumer Research 21:158164. Parrinello, G. 1993 Motivation and Anticipation in Post-Industrial Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 20:233249. Parsons, A. 2002 Brand Choice in Gift Giving: Recipient Inuence. The Journal of Product and Brand Management 11:237249. Pieters, R., and H. Robben 1998 Beyond the Horses Mouth: Exploring Acquisition and Exchange Utility in Gift Evaluation. Advances in Consumer Research 25:163169. Rucker, M., A. Freitas, and J. Dolstra 1994 A Toast for the Host? The Male Perspective on Gifts that say Thank You. Advances in Consumer Research 21:165168. Rucker, M., A. Freitas, and A. Kangas 1996 The Role of Ethnic Identity in Gift Giving. In Gift Giving. A Research Anthology, C. Otnes and R. Beltramini, eds., pp. 143162. Bowling Green: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. Ruth, J., C. Otnes, and F. Brunel 1999 Gift Receipt and the Reformulation of Interpersonal Relationships. Journal of Consumer Research 25:385402. Rynning, M. 1989 Reciprocity in a Gift Giving Situation. The Journal of Social Psychology 129:769778. Schmoll, G. 1977 Tourism Promotion. London: Tourism International Press. Sherry, J. 1983 Gift Giving in Anthropological Perspective. Journal of Consumer Research 10:157168. Sherry, J., and M. McGrath 1989 Unpacking the Holiday Presence: a Comparative Ethnography of the Gift Store. In Interpretive Consumer Research, E. Hirschman, ed., pp. 112129. Provo USA: Association for Consumer Research.

550

J. Clarke / Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008) 529550

Thornton, P., G. Shaw, and A. Williams 1997 Tourist Group Holiday Decision Making and Behavior: the Inuence of Children. Tourism Management 18:287297. Wagner, J., R. Ettenson, and S. Verrier 1990 The Effect of Donor-Recipient Involvement on Consumer Gift Decisions. Advances in Consumer Research 17:683689. Wolnbarger, M. 1990 Motivations and Symbolism in Gift-Giving Behavior. Advances in Consumer Research 17:699706. Wolnbarger, M., and L. Yale 1993 Three Motivations for Interpersonal Gift Giving: Experimental, Obligated and Practical Motivations. Advances in Consumer Research 20:520526. Woodside, A., and R. King 2001 An Updated Model of Travel and Tourism Purchase-Consumption Systems. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 10(1):327. Woodside, A., and S. Lysonski 1989 A General Model of Traveler Destination Choice. Journal of Travel Research 27(4):814. Wooten, D. 2000 Qualitative Steps Towards an Expanded Model of Anxiety in Gift Giving. Journal of Consumer Research 27:8495.

Received 27 April 2007. Resubmitted 25 November 2007. Resubmitted 22 January 2008. Accepted 17 February 2008. Refereed anonymously. Coordinating Editor: Marc L. Miller

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Place and Identity in Tourists' AccountsDocument22 pagesPlace and Identity in Tourists' AccountsΔημήτρης ΑγουρίδαςPas encore d'évaluation

- Cross-Culturel ConsDocument25 pagesCross-Culturel ConsMajid MezziPas encore d'évaluation

- Partie 2Document6 pagesPartie 2malak1lrdPas encore d'évaluation

- Ere 4001Document7 pagesEre 4001abbes18Pas encore d'évaluation

- 101 540 With Cover Page v2Document24 pages101 540 With Cover Page v2zaydbouyachouxvPas encore d'évaluation

- 7234 17536 1 SMDocument25 pages7234 17536 1 SMﺗﺴﻨﻴﻢ بن مهيديPas encore d'évaluation

- 2012arto0105 PDFDocument268 pages2012arto0105 PDFVivianelPas encore d'évaluation

- Fondements D'une Éducation ÉcocitoyenneDocument16 pagesFondements D'une Éducation Écocitoyenneipunk DafterPas encore d'évaluation

- Consommation ResponsableDocument21 pagesConsommation ResponsableSlaheddine DardouriPas encore d'évaluation

- L'écotourisme: Expérience D'une Interaction Nature-CultureDocument6 pagesL'écotourisme: Expérience D'une Interaction Nature-Culturesorabdoulaziz225Pas encore d'évaluation

- Influence de L'environnement Sur Le Comportement Du ConsommateurDocument13 pagesInfluence de L'environnement Sur Le Comportement Du Consommateurkbenmessaoud00Pas encore d'évaluation

- Currents in Environmental Education Mapping A CompDocument28 pagesCurrents in Environmental Education Mapping A CompOrkun TürkmenPas encore d'évaluation

- Roles Tourists PlayDocument20 pagesRoles Tourists PlayAnil VermaPas encore d'évaluation

- Outdoor Adventure TourismDocument18 pagesOutdoor Adventure TourismСильвия ДилиPas encore d'évaluation

- Analyse Cognitive Des Aménités EnvironnementalesDocument9 pagesAnalyse Cognitive Des Aménités EnvironnementalesHelene JoubertPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction Jeu FicelleDocument5 pagesIntroduction Jeu FicelleFilippo Lacroce FrancoPas encore d'évaluation

- La Valeur Du Produit Aux Yeux Des ConsommateursDocument15 pagesLa Valeur Du Produit Aux Yeux Des ConsommateursLakrari Tarik100% (2)

- Education A L Energie Pratiques EnseignaDocument13 pagesEducation A L Energie Pratiques EnseignaAPPOLON Le NackyPas encore d'évaluation

- Soutien à l'apprentissage autorégulé en contexte scolaire: Perspectives francophonesD'EverandSoutien à l'apprentissage autorégulé en contexte scolaire: Perspectives francophonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Intervenir-Ap - ÉcoloDocument25 pagesIntervenir-Ap - Écolopsychology00Pas encore d'évaluation

- Argentdescadeaux40990036 - CopieDocument14 pagesArgentdescadeaux40990036 - CopieFlorencia Muñoz EbenspergerPas encore d'évaluation

- Ijias 19 011 07Document6 pagesIjias 19 011 07Rachida JarrariPas encore d'évaluation

- Attraits, Attractions Et Produits Touristiques - Trois Concepts Distincts Dans Le Contexte D'un Développement Touristique RégionalDocument8 pagesAttraits, Attractions Et Produits Touristiques - Trois Concepts Distincts Dans Le Contexte D'un Développement Touristique RégionalCours De SoutiensPas encore d'évaluation

- La Didactique Du FrançaisDocument17 pagesLa Didactique Du Françaisfa_rahonPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 SES Rapport CorrectionDocument4 pages2016 SES Rapport CorrectionleopoldinewilloqueauxPas encore d'évaluation

- CULTUREDocument18 pagesCULTUREboudissa jihanePas encore d'évaluation

- Gagnon, P. (2006) - Le Loisir Et La Municipalite - ch6Document16 pagesGagnon, P. (2006) - Le Loisir Et La Municipalite - ch6la-cool-clocloPas encore d'évaluation

- Tourisme Et Chamanisme Entre Folklorisation Et Revitalisation Culturelle ?vincent BassetDocument11 pagesTourisme Et Chamanisme Entre Folklorisation Et Revitalisation Culturelle ?vincent BassetsputPas encore d'évaluation

- LemoineDocument14 pagesLemoinePatrick Philippe RifoePas encore d'évaluation

- Catalogue 2018Document75 pagesCatalogue 2018NOUREDDINE OUSAIDPas encore d'évaluation

- La Famille Et Le Phénomène de Consommation RéparéDocument34 pagesLa Famille Et Le Phénomène de Consommation Réparéboudissa jihanePas encore d'évaluation

- Économie du cadeau: Déballer l’abondance et naviguer sur la voie transformatrice de l’économie du cadeauD'EverandÉconomie du cadeau: Déballer l’abondance et naviguer sur la voie transformatrice de l’économie du cadeauPas encore d'évaluation

- Études, Revues, Livres: Revue Des Sciences de L'éducationDocument34 pagesÉtudes, Revues, Livres: Revue Des Sciences de L'éducationPrecieux MahingaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapitre 0 IntroductionDocument5 pagesChapitre 0 IntroductionCoraline LebosséPas encore d'évaluation

- Etica Del Profesional en TurismoDocument8 pagesEtica Del Profesional en TurismoAngel SanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction Trava I Let TransmissionDocument10 pagesIntroduction Trava I Let TransmissionBrunoMorenoPas encore d'évaluation

- L'approche Interculturelle Dans Le Processus D'aide The Intercultural Approach in The Support ProcessDocument22 pagesL'approche Interculturelle Dans Le Processus D'aide The Intercultural Approach in The Support ProcessMahmoud YagoubiPas encore d'évaluation

- GALANI-MOUTAFI, VasilikiDocument22 pagesGALANI-MOUTAFI, VasilikiCassia_TulPas encore d'évaluation

- La LA MEDIATION D’ELEMENTS DE CULTURE A L’ECOLE: Allier la rigueur et le plaisir pour des apprentissages signifiantsD'EverandLa LA MEDIATION D’ELEMENTS DE CULTURE A L’ECOLE: Allier la rigueur et le plaisir pour des apprentissages signifiantsPas encore d'évaluation

- Explorers Versus Planners: A Study of Turkish TouristsDocument20 pagesExplorers Versus Planners: A Study of Turkish TouristsI Ketut Surya Diarta, SP, MAPas encore d'évaluation

- Memoire Daniel DamsDocument28 pagesMemoire Daniel DamsDaniel Kam's KalumePas encore d'évaluation

- Économie écologique: Équilibrer la prospérité et la planète, un voyage vers l’économie écologiqueD'EverandÉconomie écologique: Équilibrer la prospérité et la planète, un voyage vers l’économie écologiquePas encore d'évaluation

- Kroshus Medina Laurie - Commoditizing Culture - Tourism and Maya IdentityDocument16 pagesKroshus Medina Laurie - Commoditizing Culture - Tourism and Maya IdentityGerson Godoy RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Obiblio FR 1688 - Expose MKG InterculturelDocument17 pagesObiblio FR 1688 - Expose MKG InterculturelChaimae Es-salmanyPas encore d'évaluation

- Les transitions à la vie adulte des jeunes en difficulté: Concepts, figures et pratiquesD'EverandLes transitions à la vie adulte des jeunes en difficulté: Concepts, figures et pratiquesPas encore d'évaluation

- La Clinique de L'extrême Dans Le Cadre de L'intervention Humanitaire: Le Paradoxe Du Contenant Non ContenuDocument16 pagesLa Clinique de L'extrême Dans Le Cadre de L'intervention Humanitaire: Le Paradoxe Du Contenant Non Contenujores addPas encore d'évaluation

- 12 Edso-174-33-Pedagogie-De-La-Creativite-De-L-Emotion-A-L-ApprentissageDocument14 pages12 Edso-174-33-Pedagogie-De-La-Creativite-De-L-Emotion-A-L-ApprentissageT MuschelPas encore d'évaluation

- Book-Review Katan, David Translating CulturesDocument5 pagesBook-Review Katan, David Translating CulturesWang JunPas encore d'évaluation

- 6 - Terminale - Enseignement ScientifiqueDocument19 pages6 - Terminale - Enseignement ScientifiqueuhgifhdsfhPas encore d'évaluation

- Savoirs Et Conflits de Savoirs AB OTDocument25 pagesSavoirs Et Conflits de Savoirs AB OTAngela BarthesPas encore d'évaluation

- AppropriationDocument5 pagesAppropriationMayer zattaPas encore d'évaluation

- Devoir de MédiationDocument4 pagesDevoir de MédiationjacqueschristianpublisherPas encore d'évaluation

- Pensereduc 410Document33 pagesPensereduc 410Djodyyelfayed ElfayedPas encore d'évaluation

- Comportements Du ConsommateurDocument232 pagesComportements Du ConsommateurFrédéric FaragPas encore d'évaluation

- Théorie U – Changement émergent et innovation: Modèles, applications et critiqueD'EverandThéorie U – Changement émergent et innovation: Modèles, applications et critiquePas encore d'évaluation

- Micro s2Document19 pagesMicro s2śìl šimaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cybergeo 33783Document8 pagesCybergeo 33783Al MatPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing Interne Rapport FinalDocument23 pagesMarketing Interne Rapport FinalSalwa MoumènPas encore d'évaluation

- Sport Communication Et P Dagogie La PNL Au Service D Un Coaching EfficaceDocument158 pagesSport Communication Et P Dagogie La PNL Au Service D Un Coaching EfficaceAdel OuerhaniPas encore d'évaluation

- La Gestion Des TalentsDocument5 pagesLa Gestion Des Talentsdorianyoka01Pas encore d'évaluation

- Psychopédagogie Doc-Final M2 AMEUR-AzzeddineDocument18 pagesPsychopédagogie Doc-Final M2 AMEUR-AzzeddinehafidPas encore d'évaluation

- LEXIQUEDocument25 pagesLEXIQUEAbdul KhaleqPas encore d'évaluation

- B2 - La Lettre de Demande - ModeleDocument5 pagesB2 - La Lettre de Demande - ModeleTuyen DoanPas encore d'évaluation

- Le Modèle TAMDocument3 pagesLe Modèle TAMZINEB KBYLAPas encore d'évaluation

- Communication InterneDocument40 pagesCommunication Internefadma abalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapitre 3 Outils de Connaissance de SoiDocument94 pagesChapitre 3 Outils de Connaissance de SoiNesrin souissi100% (1)

- Le ManagementDocument9 pagesLe Managementnishanth abir100% (1)

- Memoire Image Entreprise Attirer Candidat Mba Management Ressources Humaines Dauphine Executive EducationDocument67 pagesMemoire Image Entreprise Attirer Candidat Mba Management Ressources Humaines Dauphine Executive EducationA AlaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.TeamBuilding Et Motivation en Gestion de ProjetDocument16 pages1.TeamBuilding Et Motivation en Gestion de ProjetJustin Valere NiangoranPas encore d'évaluation

- MDC MotivationDocument8 pagesMDC MotivationWafae Ait lhajPas encore d'évaluation

- La Fonction D Approvisionnement Et La Gestion Des StocksDocument27 pagesLa Fonction D Approvisionnement Et La Gestion Des StocksAllache Abderrahman67% (3)

- Cours MarketingDocument56 pagesCours Marketingsouleymane sow98% (55)

- ViauDocument7 pagesViauTruica DanielPas encore d'évaluation

- Pyramide de MaslowDocument2 pagesPyramide de MaslowConstant MarcPas encore d'évaluation

- Management SituationnelDocument12 pagesManagement SituationnelKhalid RafikPas encore d'évaluation

- Texte - Vanini de Carlo Nperrin 2012 - Alignement Pédagogique PDFDocument3 pagesTexte - Vanini de Carlo Nperrin 2012 - Alignement Pédagogique PDFns5819Pas encore d'évaluation

- Influencer Persuader Motiver Alex Mucchielli Z LibraryDocument182 pagesInfluencer Persuader Motiver Alex Mucchielli Z LibraryJIDJOUPas encore d'évaluation

- 206 Modele CV ScientifiqueDocument2 pages206 Modele CV ScientifiqueEmir KaMounPas encore d'évaluation

- Ma Go e Course Sprit EntrepriseDocument11 pagesMa Go e Course Sprit EntrepriseAmine HmamouPas encore d'évaluation

- Technique Communication Master 2 2022Document16 pagesTechnique Communication Master 2 2022Dimitri Valdes TchuindjangPas encore d'évaluation