Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Narrative As Empowerment: Push and The Signifying On Prior African-American Novels On Incest

Transféré par

EleTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Narrative As Empowerment: Push and The Signifying On Prior African-American Novels On Incest

Transféré par

EleDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

NARRATIVE AS EMPOWERMENT: PUSH AND THE SIGNIFYING ON PRIOR

AFRICAN-AMERICAN NOVELS ON INCEST

Monica Michlin

Klincksieck | « Études anglaises »

2006/2 Tome 59 | pages 170 à 185

ISSN 0014-195X

ISBN 2252035439

DOI 10.3917/etan.592.00170

Article disponible en ligne à l'adresse :

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://www.cairn.info/revue-etudes-anglaises-2006-2-page-170.htm

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Distribution électronique Cairn.info pour Klincksieck.

© Klincksieck. Tous droits réservés pour tous pays.

La reproduction ou représentation de cet article, notamment par photocopie, n'est autorisée que dans les

limites des conditions générales d'utilisation du site ou, le cas échéant, des conditions générales de la

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

licence souscrite par votre établissement. Toute autre reproduction ou représentation, en tout ou partie,

sous quelque forme et de quelque manière que ce soit, est interdite sauf accord préalable et écrit de

l'éditeur, en dehors des cas prévus par la législation en vigueur en France. Il est précisé que son stockage

dans une base de données est également interdit.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Monica MICHLIN

Narrative as empowerment: Push and the signifying

on prior African-American novels on incest

This article argues that Sapphire’s novel Push (1996) is to be read as a talk-

ing book that signifies upon previous African-American novels revolving around

the three major themes of invisibility, literacy, and incest within the black family.

Focusing first on the oralized narrative of Precious’s memories of trauma and on the

empathetic reading contract her voice creates, this study examines how Precious’s

journey into literacy can be seen as a contemporary “neo-slave” or “emancipatory”

narrative, and finally how Sapphire pays tribute to Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye

(1970) and Alice Walker’s The Color Purple (1982) while critiquing them, in her

portrayal of Precious’s self-empowerment and rebirth through the “delivering” of

her own story.

Cet article propose de lire le roman naturaliste de Sapphire, Push (1996), dans

son double aspect de récit « oralisé » et de texte jouant de son intertextualité avec

des romans africains-américains célèbres ayant évoqué les mêmes thèmes majeurs de

l’invisibilité, de l’illettrisme (ou de l’apprentissage de la lecture), et de l’inceste dans

la famille noire. Si la voix de Precious permet la représentation du traumatisme tout

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

en créant un rapport empathique chez les lecteurs, son apprentissage pénible de la

lecture est le récit d’une émancipation qui se rattache à la tradition des slave narra-

tives. Finalement, on verra comment Sapphire rend hommage aux œuvres de Toni

Morrison et d’Alice Walker, tout en s’en démarquant, dans ce récit réflexif qui met en

scène la libération et la renaissance de Precious dans le processus même d’« accou-

chement » de sa propre histoire.

Sapphire’s novel Push (1996) narrates how a young black teenager

survives a childhood of physical abuse and incest. Told in Precious’s

crude and uneducated voice, it is in part testimonial, since Sapphire is

an incest survivor, albeit of middle-class background (her interviews,

her collection of poems American Dreams, or her poem “Crooked

Man” in Loving in Fear all evoke this); it is also a naturalistic novel that

reflects the lives of girls the author met working in literacy workshops

for abused teens in Harlem over the course of seven years. It is also,

Monica MICHLIN, Narrative as empowerment: Push and the signifying on prior Afri-

can-American novels on incest, ÉA 59-2 (2006): 170-185. © Didier Érudition.

EA 2-2006.indb 170 17/07/06 12:19:41

NARRATIVE AS EMPOWERMENT IN SAPPHIRE’S PUSH 171

implicitly, both a tribute to, and a critique of, prior narratives of incest

by African-American authors of the twentieth century. I will first exam-

ine how Push is a “talking book” that establishes a disturbing aural con-

nection between sixteen-year-old Precious and the readers to literally

re-present trauma in reviviscence; then show how Precious’s journey

into literacy is part of a narrative of liberation—a problematic theme in

African-American literature since Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. Last,

I will show that Sapphire deliberately signifies—signifyin’ being the

African-American term for that intertextuality whereby “black writers

read and critique other black writers as an act of rhetorical self-defini-

tion” (Gates 1987, 242)—on prior African-American novels on incest,

in particular Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye (1970) and Alice Walker’s

The Color Purple (1982), in the search for aesthetics to best enact the

dedication that opens the novel: “to children, everywhere.”

Precious begins her story in a move of aggressive self-empowerment:

“My name is Claireece Precious Jones. Everybody call me Precious.

I got three names—Claireece Precious Jones. Only motherfuckers

I hate call me Claireece” (6). This brutal variation on other first-person

famous openings such as “Call me Ishmael” or Holden Caulfield’s “If

you really want to hear about it,” goes with a commitment to the truth:

“Some people tell a story’n it don’t make no sense or be true. But I’m

gonna try to make sense and tell the truth, else what’s the fucking use?

Ain’ enough lies and shit out there already?” (4). From the outset, the

testimonial aspect of the voice is thus impossible to dissociate from

its crudeness. This literary convention, which gives the marginalized

teenager control over the narrative voice, displacing such notions as

authority and “sivilization,” can be traced back to Huck Finn; while it

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

allows a reversal of hierarchies (social and literary), it also functions as

stand-up comedy, and as a defense against melancholia or depression (if

one thinks, for instance, of Holden’s provocations in The Catcher in the

Rye). Precious—like Claudia in The Bluest Eye—tells us from the very

first paragraph that she is having her “fahver’s” baby for the second

time, so that the double shock of voice and theme are made immediate,

rather than mediated, by the “in-your-face” voice that immediately

speaks the unspeakable.

The actual description of what Precious has endured, though, is

delayed; given the psychological need to repress traumatic memo-

ries, these are conveyed piecemeal, through a jigsaw-puzzle of horrific

scenes, whenever the present triggers an episode of post-traumatic

stress. The flashbacks to the abuse become less frequent as Precious

finds a new community at the Each One/Teach One alternative school

and starts to build a life of her own (9, 18, 19-21, 24, 32, 36, 38-39, 59,

63), but they reemerge when she is told she must talk about her past

(111-12), and when this past returns to haunt her (129, 132, 135-36).

Because her suppressed memories resurface without warning, read-

ers are caught off guard too. Sapphire uses onomatopoeia, exclama-

tives, italics (“wump!”), block letters, the overlay of blows and insults,

EA 2-2006.indb 171 17/07/06 12:19:43

172 ÉTUDES ANGLAISES, T. 59, N° 2 (2006)

and the mise en abyme of episodes, to make us feel we are suffocating

and cannot return to the “surface” of the text, caught by the undertow

of trauma. For instance, when, pregnant for the second time, Precious

remembers how her mother almost killed her when she came home

from having her first baby at the age of twelve, the flashback takes place

in real time, over a dozen pages.

Naturalistic narrative does not preclude Sapphire’s revising of

other genres, such as the fairy tale, portraying Precious’s mother as an

ogress:

Devil red sparks flashes in Mama’s eyes, big crease in her forehead git

deeper . . . . She take up half the couch, her arms seem like giant arms, her

legs which she always got cocked open seem like ugly tree logs. (20).

More brutally than Bettelheim, Sapphire reveals the story so many

fairy tales actually tell: Precious’s mother beats her, forces her to cook

for her, to overeat with her, and finally, in the last seconds of this scene,

uses her sexually (the “cocked legs” now reading like a sordid pun). As

Precious passes out from too much cumulated abuse, and readers feel

they can read no more, her voice cuts back to the present, in the “now”

where she is sixteen and pregnant again: “all been getting mixed up in

my head. . . . Everything seem like clothes in washing machine at laun-

dry mat—round’n’round, up’n down” (22). While this is an apt reflexive

image for the narrative itself, the image of dirty laundry of course reads

as that of family secrets being revealed to the reader.

Everything in Precious’s life is both “mixed up” and connected: abuse

at home leads to illiteracy at school. Not only is Precious mocked for the

verbal symptoms of abuse (“Secon’ grade they laffes at HOW I talk,”

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

36), but she is humiliated for the physical symptoms too (“thas when

I start to pee on myself,” 36). Trapped in yet another situation of psy-

chological violence—“Secon’ grade teacher HATE me. Oh that woman

hate me” (36)—she dissociates:

I stare at the blackboard pretending. I don’t know what I’m pretending—

that trains ain’ riding through my head sometime and that yes, I’m reading

along with the class on page 55 of the reader. Early on I realize no one

hear the TV set voices growing out blackboard but me, so I try not to

answer them. . . . Me sitting in my chair at my desk and the world turn to

whirring sound, everything is noise, teacher’s voice white static. My pee

pee open hot stinky down my thighs sssssss splatter splatter. I wanna die

I hate myself HATE myself. Giggles giggles but I don’t move I barely

breathe I just sit. They giggle. I stare straight ahead. They talk me. I don’t

say nuffin’.

Seven, he on me almost every night. First it’s just in my mouth. Then it’s

more more. He is intercoursing me. Say I can take it. Look you don’t even

bleed, virgin girls bleed. You not virgin. I’m seven. (39)

The vivid use of the present tense, but also of onomatopoeia, repeti-

tion, childish syntax and vocabulary (“my pee pee”), emphasizes that

Precious speaks in the voice of the seven-year-old she was then. The use

EA 2-2006.indb 172 17/07/06 12:19:45

NARRATIVE AS EMPOWERMENT IN SAPPHIRE’S PUSH 173

of duplication, as in “splatter splatter” or “I hate myself HATE myself,”

and the arrested syntax implied by the repetition of the same word,

illustrate her traumatized numbness, and the self-erasure she seeks as

an ultimate refuge (this stylistic figure reappears each time Precious is

thrown into extreme anxiety: “I feel panicking panicking—I don’t know

alphabetical order—whas that!” [51], or “I want die I want die” [53]).

It also shows how the abuse at school and at home mirror each other,

in a relentless chain of pain. The image of the trains driving through

Precious’s head is one of rape (“to put a train on someone” is a ghetto

image for gang rape); only later will she find out that metaphorical

trains can mean liberation, when she learns about the Underground

Railroad at the Alternative School with her teacher/savior, Ms Rain.

The removal of punctuation (“I don’t move I barely breathe”) reflects

how she tries to self-erase; while the incorrect use of the transitive “they

talk me” symbolically highlights how she is not spoken to, but reified

and undone by others’ speech. The fact that there are noticeably no

quotation marks around the father’s insults and taunts conveys how his

voice destroys Precious’s self-image while he is raping her. Only as she

narrates this episode can she finally speak up for the child who couldn’t

“say nuffin’” (49)—hence her use of the present tense, and of italics, to

reassert the unacceptable reality: “I’m seven.”

Being expelled from high school at the beginning of the novel turns

out to be a blessing in disguise. Redirected to an alternative school,

Precious is about to discover literacy. At first, she is overwhelmed by

terror: “my head is big ’lympic size pool, all the years, all the me’s float-

ing around glued shamed to desks while pee puddles get big near their

feet” (40). This is due to Precious’s exhibiting every symptom of “com-

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

plex post-traumatic stress disorder” (Herman 121): “hyperarousal”

(35) and “intrusion” of traumatic memories (37) explain the “triggering

effect” of sights or sounds related to past situations of terror: similarly,

she swings between traumatic memories and amnesia, or moments of

dissociation (Freyd 86-92), which function as a (dangerous) coping

mechanism. However overwhelming her initial terror of the alterna-

tive school, however, by admitting she is “illiterit” (47), Precious finds

a “place” (48) for the first time. Even the very first lesson, learning the

alphabet again, turns into a magical charm that counteracts memories

of abuse: that very night, she dreams that the alphabet allows her to

play the “good” Pied Piper to herself, against the abusive mother who

once again preys on her in her nightmare:

I squeeze my eyes shut but choking don’t stop it get worse. Then I open

my eyes and look. I look at little Precious and big Mama and feel hit fee-

ling, feel like killing Mama. But I don’t, instead I call little Precious and

say, Come to Mama but I means me. Come to me little Precious. Little

Precious look at me, smile, and start to sing: ABCDEFG . . . (59)

The alphabet is also the start of Precious’s written self-expression:

when Ms Rain asks her to write one word for each letter, this list

EA 2-2006.indb 173 17/07/06 12:19:47

174 ÉTUDES ANGLAISES, T. 59, N° 2 (2006)

turns into an inventory of the pain and degradation she has endured

(“dog, evil like mama, fuck, gun, home, kill, North America, open,

punks, stop, two ton, zonked”), but also, of her feelings of hope

(“Africa, Baby, black colored, Farrakhan real man, home, I some-

body, Jermaine, love, main man Malcolm, Queen Latifah, respect,

vote, well”). Although “Farrakhan real man” points to Precious’s

alienation, she means it as synonymous for black pride; the respect-

ful familiarity of “main man Malcolm” points to this too, while

“Jermaine” (Precious’s classmate) and Queen Latifah (the singer)

embody proud black (lesbian) womanhood, and “I somebody” of

course asserts Precious’s preciousness. So that when Precious says

of this list “Them words everything” (66), she means that all of her

life can be expressed through these words, but also that words are

her salvation. The layout of the list irresistibly calls to mind that of a

poem, even before Precious experiments with poetry (90-91, 99-105,

126-28), and finally includes two poems in the “Life Stories” class

project the novel ends on.

The aesthetic difficulty is to materialize Precious’s learning how to

write, in a book which is necessarily all writing from cover to cover. The

paradox we are asked to accept is that the initial voice was spoken, as if

on tape, without this being the explicit frame of the narrative—contrary,

say, to Ernest Gaines’s The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1971),

or Stewart O’Nan’s The Speed Queen (1996), a novel which actually

substitutes to a title like “Part I” the label “Side A.” The inset book of

Precious’s journey into literacy appears through inserts of her journal,

which Ms Rain “translates” line by line, in italics, and answers with

new questions, compliments, or objections. We thus become aware

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

of Precious’s illiteracy only when her fluent oral voice is already so

familiar to us that we are ready to take the trouble to decipher her

garbled writing. Entire pages of the novel are thus in “double” writing,

Precious’s almost undecipherable words, with their missing syllables or

vowels, followed by the literate version (61, 65-66, 69-73, 89-93, 98-106).

The problem with this representation of literacy is that Precious’s voice

seems to regress because her voice reads like “baby talk” even as she is

making progress in her acquisition of writing.

For readers not to be alienated by the reflexive process of being

taught to read again, Sapphire eventually has Precious resume her oral

narrative. She refocuses Precious’s apprenticeship of literacy, beyond

the technical aspects of language, on her “unlearning” her condition-

ing by years of sadistic treatment. Within this context, TV is used as

a symbol of illiteracy—it is the only form of “culchure” in Precious’s

home—and one which is always connected to the abuse:

I think my mind a TV set smell like between my muver’s legs. I stupid.

I ain’ got no education even tho’ I not miss days of school. I talks funny.

The air floats like water wif pictures around me sometime. Sometimes

I can’t breathe. (57)

EA 2-2006.indb 174 17/07/06 12:19:49

NARRATIVE AS EMPOWERMENT IN SAPPHIRE’S PUSH 175

I am a TV set wif no picture. I am broke wif no mind. No past or present

time. Only the movies of being someone else. Someone not fat, dark skin,

short hair, someone not fucked. A pink virgin girl. (112)

What literacy brings is the exact opposite: a means of expression, a

possible to create and to recreate herself, and to share her story with

others. At the heart of the novel is the idea that Precious can overcome

both her awful past and unbearable present and give birth to a new

self. This is highlighted through the return of the word push at pivotal

moments in the story. First, when a Hispanic paramedic encourages her

when she is in labor with her first child:

He say, “Precious, it’s almost here. I want you to push, you hear me momi,

when that shit hit you again, go with it and push, Preshecita. Push.” And

I did. (10).

The night before Precious’s first day at the Alternative School, this

guardian angel figure appears in her dreams: “Push, Precious, you gonna

hafta push” (16). The next day, when Precious admits she is “illiterit”

(47), Ms Rain encourages her with the same words: “But for now, I want

you to try, push yourself Precious, go for it” (54); and again, when Pre-

cious must move on to writing: “Write what’s on your mind, push your-

self to see the letters that represent the words you’re thinking” (61).

The fact that the imperative “push” is most often voiced by Ms Rain

illustrates how the novel associates literacy, empowerment, and the dis-

covery of collective strength, whether in the classroom, through black

history, or through black literature. This is obvious when Precious runs

away from her abusive family, and helped by Ms Rain, finds refuge in

Langston Hughes’s house. Being symbolically housed by the poet of

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

black dreams, and of the black vernacular, allows a redefinition of kin-

ship from the family cell to the inspirational ancestor. This positive lit-

erary ancestor-figure is to be contrasted with the absence of a loving

grandmother—a figure like Baby Suggs in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, or

Mama Day in Gloria Naylor’s eponymous novel, to quote only two—

as Ms Rain puts it, when Precious quotes her real-life grandmother’s

uncaring platitudes: “where was your grandmother when your father

was abusing you?” (71).

Precious’s inventory of the books she owns similarly reads like the

matrilineage she can find strength in: that of black women who write

about the resistance to oppression (80-81). While asserting her belief

in the liberating role of committed African-American literature—the

fact that literature changes the world, by changing representations of

the world, and raising readers’ consciousness—Sapphire suggests that

Precious too can participate in that liberation by sharing this heritage

in turn. When Ms Rain, Sapphire’s spokesperson in the novel—Blue

Rain is a clear pun on Sapphire—has the class read The Color Purple

(CP), Precious says: “We reading The Color Purple in school. Which is

really hard for me” (81); by this she means that it is difficult technically

(because she is barely literate), but also emotionally (because of the

EA 2-2006.indb 175 17/07/06 12:19:52

176 ÉTUDES ANGLAISES, T. 59, N° 2 (2006)

mirroring effect of Celie’s story). Contrary to the Kirkus Review’s

charge when the novel came out, Sapphire did not quote CP out of

“commercial aspirations,” but out of the double desire to validate

Walker by having a contemporary abuse survivor identify with Celie a

generation on, and to authenticate her own narrative by having Precious

comment on the testimonial authenticity of Walker’s novel (83). We are

forewarned, however, that Push is also a critique of its forerunner:

Things going good in my life, almost like The Color Purple. . . . Ms Rain

say one of the criticisms of The Color Purple is it have fairy tale ending.

I would say, well shit like that can be true. Life can work out for the best

sometimes. Ms Rain love Color Purple too but say realism has its virtues

too. (83)

Indeed, just when Precious seems safe, her abusive mother reemerges

to bring new hurt: Precious’s father had AIDS (and has just died). When

Precious tests HIV positive, the limits of literacy and counter-narrative

become brutally clear: there can be no escape from the past, no total

“closure” because of the permanence of the body, and the continued

damage wreaked by the now-ended abuse. Later, in a telling slip of the

pen on “Rain,” which she misspells “Ran,” and on “past,” which she spells

“pass,” Precious expresses both her defeated hopes, and her enduring

hope that she can still, like Harriet Tubman, run from the bondage of

the past, and pass into freedom: “BUT I was gon dem / I escap dem like

Harriet/ Ms Ran say we can nt escap the pass.” (101). But before she

can come to this ambivalent acceptance, Precious almost gives up. This

is the last, crucial time Ms Rain tells her to push:

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

I don’t have nothing to write today—maybe never. Hammer in my heart

now, beating me, I feel like my blood a giant river swell up inside me

and I’m drowning. My head all dark inside. Feel like giant river I never

cross in front of me now. Ms Rain say, You not writing Precious. I say I’m

drownin’ in river. She don’t look at me like I’m crazy but say, If you just

sit there the river gonna rise up drown you! Writing could be the boat

carry you to the other side. One time in your journal you told me you had

never really told your story. I think telling your story git you over that

river Precious.

I still don’t move. She say, “Write.” I tell her, “I am tired. Fuck you!”

I scream at Ms Rain. I never do that before. Class look shock. I feel

embarrass, stupid; sit down, I’m made a fool of myself on top of everything

else. She says, “Open your notebook Precious.” “I’m tired,” I says. She

says, “I know you are but you can’t stop now Precious, you gotta push.”

And I do. (96-97)

Writing her life story cannot undo Precious’s past; but it can be

her buoy into survival. The water imagery means drowning but also,

redemption and escape, the way it does in spirituals—“I wonder / How

I got over / You know my soul / Looks back in wonder / How did I make

it over?” (“How I Got Over”). This gives this passage heightened sym-

bolic meaning, as it underscores how Precious’s voice and Sapphire’s

EA 2-2006.indb 176 17/07/06 12:19:54

NARRATIVE AS EMPOWERMENT IN SAPPHIRE’S PUSH 177

work stand rooted in an African-American oral tradition. The sti-

chomythic dialogue, Ms Rain’s imperatives and Precious’s reiteration

of her absolute weariness, create intense (melo)dramatic tension, which

is resolved in Precious’s “I do” which resonates performatively as the

final words of this chapter, and of Part Three. The blank part of the page

that follows the “I do” also embodies the engulfing void over which

Precious must travel. Her identification with Harriet Tubman, the cel-

ebrated Black heroine who went back to the South as a “conductor”

of the Underground Railroad, risking her own life over and over again

to save hundreds of her people, emphasizes how Push is to be read as

a neo-slave narrative—depicting her escape from both racial discrimi-

nation and entrapment within her abusive family (Octavia Butler and

Gloria Naylor also rework abuse within the black family or community

and racial oppression in “split” neo-slave narratives: Kindred and the

stories in Bloodchild; Linden Hills and Bailey’s Café).

Forcing herself to go beyond the half-way mark means filling in the

gaps of her narrative, even/especially if it means recounting how rape

used to push her into extreme self-abuse, out of despair, and the inter-

nalized feeling of abjection: by telling, Precious can cleanse herself of

the feelings of shame. Readers are expected to react against her self-

blame (“Is it my fault because I didn’t talk to the polices?” 125), and

to understand that the child-protagonist’s smearing herself in feces or

cutting herself with a razor (112) were inadequate substitutes, then, for

writing, now. Instead of staying imprisoned within the infra-verbal, Pre-

cious can now create collages of the verbal and non-verbal, with draw-

ings, such as the happy face (101) or the crying eye (102), that express

what her literary voice does not yet allow her to. In the same way, the

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

crossed-out words on page 101 highlight how her journal is a work-in-

progress. As her reading and writing skills improve from page to page,

so does her political and literary consciousness: she explicitly revises

Langston Hughes’s Harlem, opposing the sordid lyricism of a land-

scape of crack addicts and dirty lots to his lyrical imagery of a “jazzee

Harlem” (102). When Precious copies his poem “Mother and Son” as

a tribute to the poet, but also, to her love for her own son, she revises

the text through contextualization, admitting that she would rather not

have had to give birth: “cause even if I not raped, who want a baby at

twelve! . . .) Hours hours push push push!” (114).

What she gives birth to now is meaning, by becoming the “passer-on”

for others’ stories. After having announced this explicitly—“One day

when I have time I read you what the other girls wrote” (94)—she lets

us read Rhonda’s, Jermaine’s, and Rita’s stories in the “Life Stories /

Class Book.” This last section of the book has no page numbers, and is

set in different type, like an inset document. Each of the stories portrays

incest, abuse, and subsequent patterns of self-destruction (drug addic-

tion, prostitution, violence). The two texts, Precious’s story, and the class

book, are authenticating each other. Since Precious’s own story does

not appear in the “Life Stories” section at the end of the book, it seems

EA 2-2006.indb 177 17/07/06 12:19:55

178 ÉTUDES ANGLAISES, T. 59, N° 2 (2006)

obvious that her entire narrative is that “Life Story.” Her voice thus

forms a loop back to the beginning of the text, in a perfect example of

“self-authorization”: “Ms Rain say we got to write now in our journals.

Say each of our lives is important. . . . Say each of us has a story to tell”

(96). Precious thereby achieves the essential goal of the Each One/

Teach One school—to help others “push” themselves: “Only now I the

one who say ‘keep on keepin’ on!’ to new girls” (94).

Push is also very much about Precious’s learning how to read the

Other’s text about her, for instance when she “steals” the file her white

caseworker, Ms Weiss (an unsubtle pun on the white power-system)

keeps on her. Ms Weiss despises Precious: her report illustrates how

language is power and how “file” should be read dyslexically, as an ana-

gram of “life.” Precious has already expressed earlier on that the file is

part of the abuse:

I don’t know what file say. I do know that every time they wants to

fuck wif me or decide something in my life, here they come wif the

mutherfucking file. (28)

As she finally reads it, she perceives that behind the well-written,

technocratic language, lies a social death sentence. While she still feels

some difficulty deciphering complex words (118), she aptly translates

into “slavry” (121) the decision to force her into workfare, despite her

very young age (eighteen). This episode stages what happens when those

who are constantly the object of definition in a society that oppresses

them suddenly read what was never meant for their eyes: terms like

“obvious limitations” (121), which stigmatize Precious, abuse her anew:

“She look at me like I am ugly freak did something to make my own

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

life like it is” (124).

While Sapphire is clearly working on the referential issues of the con-

nection between sexual abuse, poverty, illiteracy, and the racist white

gaze, she is also, as an African-American writer, signifying on an already

established body of African-American texts that deal with three funda-

mental issues: invisibility, incest, and literacy as liberation. Since Ellison’s

Invisible Man, the conceit of blackness as invisibility has been the object

of constant revision; Sapphire’s version of this trope revises Toni Mor-

rison’s The Bluest Eye, and the scene in which Pecola, the deprived and

abused little black girl cannot be “seen” by the white grocer:

At some fixed point in time and space he senses that he need not waste the

effort of a glance. He does not see her, because for him there is nothing to

see. How can a fifty-two-year-old white immigrant storekeeper with the

taste of potatoes and beer in his mouth . . . see a little black girl? (36)

In Push, Precious expresses this denial of her existence in her own

voice:

I big, I talk, I eats, I cooks, I laugh, watch TV, do what my muver say.

But I can see when the picture come back I don’t exist. Don’t nobody

EA 2-2006.indb 178 17/07/06 12:19:58

NARRATIVE AS EMPOWERMENT IN SAPPHIRE’S PUSH 179

want me. Don’t nobody need me. I know who I am. I know who they say

I am—vampire sucking the system’s blood. Ugly black grease to be wipe

away, punish, kilt, changed, finded a job for. (31)

The vampire image is used in its double sense of invisibility and of

feeding off others: this is Sapphire’s angry rephrasing of the stigmatiza-

tion of single black mothers in the drive towards “welfare reform” at the

time this book was written—indeed, the 1996 Personal Responsibility

and Work Reconciliation Opportunity Act put a 5-year lifetime limit

on welfare, forcing poor women from welfare into work, and making

escape from poverty practically impossible (and even Sapphire could

not imagine that Congress would refuse to raise the so-called “mini-

mum wage” of $5.15 from 1997 onwards). The text revolves around the

opposition between Precious’s activity, through the accumulation of

verbs, her extreme physical presence (“I big”) and the fact that she does

not exist—the verb “to be” is suppressed, while several terms (“disap-

pear,” “I don’t exist”) repeat society’s obliteration of her. The antithesis

between “I know who I am” and “I know who they say I am” is the

very core of the novel: because we are within Precious’s mind, we lose

track of “exterior” perceptions of her as obese, pregnant, and “ugly.”

Although “grease” acts as a double image, for her obesity, and for her

being accused of “living off the fat” of the land, this appalling reification

summarizes the scapegoating, both symbolic and literal, of black people

in America over the past four centuries.

The second topos that Push reworks is that of incest within the black

family, in a critique both of CP and BE. CP was already a transtextual

variation on BE, which itself was Morrison’s “intertextually charged

revision of the Ellisonian depiction of incest” (Awkward 62). The ini-

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

tial text is defined by the incestuous father’s perspective: Ellison lets

the illiterate poor black man, Trueblood, claim that he cannot be held

responsible for incest that took place while he was still dreaming in

sleep. Morrison, in her rewriting of the theme, depicts her character,

Cholly Breedlove—the onomastics, in both Ellison and Morrison, draw

attention to the perverse meaning of “blood” or “love” in the dysfunc-

tional and abusive family—as a rapist, conveying in sordid lyricism the

ambivalence of his feelings (“hatred mixed with tenderness,” 129) and

his literally sick desire for his child (“his hatred of her slimed in his

stomach and threatened to become vomit,” 127). The entire scene is a

replay of Cholly’s own traumatic scene of sexual initiation. Morrison

highlights this by focusing on the loosening of Cholly’s anus as he rapes

Pecola (BE 128), in an echo of the symbolic rape by white men that he

experienced then: “the flashlight [on his buttocks] wormed its way into

his guts and turned the sweet taste of muscadine into rotten fetid bile”

(BE 116). This unusual “devirilization” of the rapist obviously con-

veys Morrison’s refusal to glamorize sexual violence—but the primary

meaning is that Cholly is caught in this repetition of sweetness turning

to bile, or semen to vomit, when he violates his child as he himself was

symbolically violated.

EA 2-2006.indb 179 17/07/06 12:19:59

180 ÉTUDES ANGLAISES, T. 59, N° 2 (2006)

Sapphire, in turn, revises this scene in her depiction of incest from the

child’s perspective. While Morrison is an uncontestable craftswoman

of lyrical language, the very beauty of the imagery used in BE—the

oxymoron “the dry harbor of her vagina” (128), or the play on the

literal and the symbolic in the image of Pecola as punctured balloon

in the scene of the rape (128)—is problematic. Although the very

incongruity of the beautiful images is, arguably, violent beyond the

mere specularity of crude terms for violent acts, formal beauty creates

a deep malaise—not that of voyeurism, but that of being to a degree

aligned with the rapist, in feeling the aesthetic pleasure of the text even

as it narrates unspeakable cruelty. Sapphire rejects these ambiguities

of the BE as well as its final pages which celebrate Cholly for being

a “free man” (163) and assert that he loved Pecola—an example of

narrative contamination by the perverse character’s warped logic and

vocabulary.

For the same reason, Sapphire refuses the chapter-long flashbacks

into the abusive parents’ pasts that are fundamental to BE. The overall

structure of BE, its polyphony, its web of imagery (a broken tooth, the

stain of dark berries) which connects the abusive parents’ stories, con-

textualizes the abusers’ actions within a broader frame of dispossession

and oppression, which, in fine, justifiably humanizes them, but in doing

so, dilutes the abused child’s perspective—even when the collusion

between the rapist father and the violent mother is brilliantly captured,

for instance when the rape scene and the chapter end on:

So when the child regained consciousness, she was lying on the kitchen

floor under a heavy quilt, trying to connect the pain between her legs with

the face of her mother looming over her. (129)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

While abuse is indeed related to trans-generational repetition, Sap-

phire explicitly underlines that the role of the child-narrator is not to

argue this psychoanalytical aspect of her parents’ past—if the victim is

telling the story, it is ideologically necessary not to explain, and ration-

alize. Push dramatizes the moment when Mama’s inset story could

surface—“I cry for every day of my life. I cry for Mama what kinda

story Mama got to do me like she do?” (96)—and deliberately refuses

to allow it, marking this narrative as the space where Precious, not

“Mama,” speaks and (re)constructs herself. When Precious’s “Muver”

does speak up in the interview with the social worker (135-36), her

speech is used against her, as she (insanely) describes how she felt jeal-

ous, not horrified, when her husband first raped Precious as a baby still

in diapers. By portraying Precious’s mother as a rapist herself, Sapphire

creates, what is, to the best of my knowledge, the first literary repre-

sentation of explicitly genital maternal violence, thus going beyond the

helpless or physically abusive mothers represented in either CP or BE,

and beyond, too, the collusive or battered mothers portrayed in poor

white Southern fiction such as Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Caro-

lina or Jim Grimsley’s Winter Birds.

EA 2-2006.indb 180 17/07/06 12:20:02

NARRATIVE AS EMPOWERMENT IN SAPPHIRE’S PUSH 181

These choices of perspective and narrative voice are fundamentally

political. Although Morrison’s depiction of the intergenerational con-

struction of abuse is realistic, and although BE ends on the poignant

lament of collective guilt in the victimization of Pecola, the very struc-

ture of the novel is ambiguous in that it silences the child, in what could

be read as an additional move of abuse and victimization (Morrison’s

own Afterword [BE 167-72] analyzes this difficulty). Claudia’s voice

cries out against a racist, classist, and sexist society that destroys some

of its native daughters, in a loaded reference to Wright’s Native Son:

I even think now that the land of the entire country was hostile to

marigolds that year. This soil is bad for certain kinds of flowers. Certain

seeds it will not nurture, certain fruit it will not bear, and when the land

kills of its own volition, we acquiesce and say the victim had no right to

live. We are wrong, of course, but it doesn’t matter. It’s too late. At least,

on my edge of the town, among the garbage and the sunflowers of my

town, it’s much, much, much too late. (164)

But the fact that Pecola does not survive psychically and that the

story is told by everyone but her is one of the things that feminist writ-

ers have necessarily revised since.

As Pin-Chia Feng has argued in The Female Bildungsroman, the

“minority female bildungsroman” is already primarily a counternar-

rative (18). Feng argues convincingly that through such techniques

as palimpsest, re-presentation, “re-memory” (taken from Morrison’s

Beloved), or images that signify haunting, minority female writers can

highlight, rather than erase, the previous invisibility and/or marginali-

zation of the voices of females of color. Yet Feng agrees that although

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

BE plays on presence and absence, fragmentation, and decenters the

male and/or white voice, the novel ultimately fails, because of the sense

of “over-determination to Pecola’s tragedy” and the fact that she is

caught in Claudia’s narrative, or in the ominiscient narrative voice, in

an “unbreakable discursive prison” (57). This is exactly what first Alice

Walker, then Sapphire have tried to avoid in CP and Push. CP revital-

ized the epistolary novel: Celie addresses herself to God, thus obey-

ing—but circumventing, given that the true addressees are the read-

ers—her incestuous father’s silencing threat: “You better not never tell

nobody but God.” In its use of colloquial authenticity, black dialect,

crude sexual vocabulary, and childish syntax, CP is a direct ancestor to

Push, seeking the illusion of direct, uncensored speech; its faults do not

lie in this choice of voice, but in the unrealistic ending, its mapping out

of escapism in an exoticized Africa, its eventual watering down of pain

and conflict. Push explicitly and formally avoids these pitfalls, placing

Precious firmly in Harlem in 1996, and allowing her the space of class-

room and literature as sole spaces of escape.

Sapphire’s depiction of literacy as a stepping-stone to freedom relies

on her distinguishing the official classroom from the alternative, black

feminist school: this allows her to revise the defeatism of BE, without

EA 2-2006.indb 181 17/07/06 12:20:04

182 ÉTUDES ANGLAISES, T. 59, N° 2 (2006)

losing its charge against the class-based and racially oppressive public

school system. Morrison’s BE attacks the school system by turning its

lies back on itself: the novel is preceded by a liminary text, a single para-

graph taken from the “Dick and Jane” primer most children learned to

read from then, which describes an idyllic (implicitly white) family. The

text is then repeated without punctuation, and then, without the blanks

between words, in a “rewriting” that resembles a “crushing” into illeg-

ibility, the last version turning into a frightening compression/amputa-

tion of the original body of the text. Pecola’s story is thus placed under a

rebuttal of the clichés on “family values” and a rebuttal of the “simple”

(in the meaning of stupid, too) text of the “reader”—the whole novel is

thus, as D. Gibson puts it, a “counter-text” to the destroyed “authoriz-

ing” text, shreds of which are then pointedly used as antiphrastic heads

of chapters. The narrative violence imposed on both the body of the

text, and on us as readers is part of a symbolic immersion into Pecola’s

story; as Donald Gibson put it, we are being taught how to read again,

from the black child’s perspective—but in an unbelievable twist, Gib-

son manages to misread the rapes as perhaps having been enjoyable for

Pecola. What the compression of the text also forces upon us, through

its elimination of spaces between words, is the absence of boundaries

between parent and child in abuse: new words are formed that her-

ald the rape (“fatherdick”), and the tearing apart of the initial text to

form chapter-heads can be seen as the destruction of Pecola’s body and

spirit, but also, the paradoxical “reconstruction,” shred by shred, of the

taboo story that the clichés of the primer masked.

As opposed to this, Sapphire makes her story a neo-slave-narra-

tive in which literacy means the freedom for Precious to create her-

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

self as subject, where her parents’ (and white institutions’) speech and

physical abuse unmade her. In Ms Rain, Sapphire revises black texts

on the black teacher. Morrison, like Ellison, often casts the connection

between literacy and liberation as a fallacy—even if her own praxis as

writer belies this—and the teacher as oppressor: in Song of Solomon,

the oral heritage frees black people where the written word denies

them; in Beloved, the Schoolteacher uses language as a weapon of dehu-

manization against Sethe. Yet, also in Beloved, the black schoolteacher

ultimately saves Denver and Sethe. Ernest Gaines also swings between

the petit-bourgeois black teacher who despises the poor black children

who are his charges but whom he sees as a burden (the narrator in A

Lesson Before Dying) and the black teacher as liberator (Ned in The

Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman). Sapphire simplifies the dialectics

of liberation and oppression within the school-system by opposing the

ideal black teacher (helper, friend, and substitute family), Ms Rain, as

counter-model to the abusive black parents and to white public school

system. Ms Rain is a double of the militant black teacher in Toni Cade

Bambara’s “The Lesson;” but where this teacher’s political lessons

are resisted by the feisty little girl she is trying to educate—Elizabeth

Muther brilliantly analyzes Toni Cade Bambara’s “feisty girls”’ “resist-

EA 2-2006.indb 182 17/07/06 12:20:06

NARRATIVE AS EMPOWERMENT IN SAPPHIRE’ PUSH 183

ance narrative” against racial, gender, and class oppression alike—and

whose vernacular stays rebellious, Ms Rain’s lessons are quickly inter-

nalized, to her benefit, by Precious. Just as slang and curses in “The Les-

son” are part of addressing the reader-as-peer—a basic dynamic of all

contemporary teenage voices in literature, including Push—and just as

the black vernacular’s political charge is to raise a black feminist con-

sciousness within the short story, as Janet Ruth Heller has deftly shown

(Heller), so too does Sapphire use the crudeness of Precious’s voice

in Push to simultaneously create complicity with her character, and to

pass on her resistance to/acceptance of Ms Rain’s “lessons.”

While Ms Rain may seem too good to be true—part of the “perfect-

teacher” syndrome that has inspired characters like Michelle Pfeiffer’s

in Rebel Minds—Sapphire’s double investment in this character is

obvious: through this idealized self-portrayal, she is asserting that the

poor urban black community needs to distinguish false models (Louis

Farrakhan) and real ones (the committed lesbian teacher). This double

signifying on teachers and preachers, and on “family values” and

homosexuality, makes the novel an important one within lgbt (lesbian

gay bisexuel transsexual) literature. Ms Rain’s sexual orientation is

essential to the novel’s critique of homophobia; but also to creation

of a “hall of fame” of gay or lesbian characters in African American

fiction. Sapphire is clearly intent on furthering a double African-

American tradition: that of black feminism, and that of black lgbt

authors which she simultaneously charters and expands through her

own creation of Ms Rain as lesbian heroine. This is why all the authors

explicitly quoted in Push are presumably gay, Langston Hughes being

the case in point—see Julien Isaac’s film Looking for Langston, or the

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

true significance of the adjective “asexual” volunteered by Rampersad

(1986, 35, 133)—or overtly lesbian (Audre Lorde, etc.). “Ms Rain” also

reads as a pun on Ma Rainey, one of the first female blues singers, and,

according to Angela Davis, one of the first out lesbian singers—and, of

course, “Sapphire” is a pun on the mythical founder of lesbian writing,

the Greek poetess Sappho. The superimpression of Ma Rainey and

Sappho is also that of the black vernacular and of literary classicism: it

shows the distance between Sapphire and her protagonist, who knows

neither of the figures quoted above. Significantly, Ms Rain’s sexual

orientation functions only as a political sign—there is no lesbian love

story in Push, in part due to the choice of narrator (Sapphire certainly

did not want Ms Rain to be perceived as seducing Precious), but also,

perhaps, because the anxiety of influence associated with CP was too

intense, dissuading Sapphire from trying to create a love story that

would compete with Celie’s and Shug’s. On the other hand, one might

also argue that all of Push is the unfolding of a love story: between

Precious and the homosocial community of her classroom, as well

as between Precious and us. Despite what is sometimes said to the

contrary, readers’ reactions predictably fall along the lines of this

defining aspect of the novel: only a minority of male readers will read

EA 2-2006.indb 183 17/07/06 12:20:08

184 ÉTUDES ANGLAISES, T. 59, N° 2 (2006)

the novel with sympathy or empathy instead of resisting it (to quote

Judith Fetterley in a reversed context).

Written out of autobiographical pain and political commitment,

Push is a disturbing and poignant literary work, which signifies upon

the depiction of incest in African-American literature. As Precious

reworks trauma into speech, implicitly turning her “life story” into

the novel we have before us, she teaches us to see those whom society

continues to consider as ugly, contemptible, exploitable and disposable,

as precious human beings. The literary beauty of the novel lies

precisely in its speakerly authenticity as it performatively enacts what

Farah Jasmine Griffin has called “textual healing.” Although writing,

in a deliberately reflexive play on rebirth, only laboriously becomes

“a site of healing, pleasure, and resistance,” it undoubtedly manifests

in Angelyn Mitchell’s terms (144-50) its “transformative potential”

and “curative value” both for the protagonist and for the readers. It

is thus a “liberatory narrative” in the sense that A. Mitchell applies

to contemporary black women’s neo-slave narratives (in particular,

Toni Morrison’s Beloved [1987], Octavia E. Butler’s Kindred [1979]

and Sherley Anne Williams’s Dessa Rose [1986]). The voice Sapphire

has written into life may strike some as being too sordid, or too

campy; but to others, it is truly inspirational—all the more so since

Sapphire respects the ultimate reading contract of any committed

novel—something Toni Morrison evokes as a test of her own writing

(“Whenever I feel uneasy about my writing, I think: “what would be

the response of the people in the book if they read the book? That’s

my way of staying on the track. Those are the people for whom I write”

[Le Clair 371]): to be readable, in every way, with no loss of dignity for

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

her, by Precious herself.

Monica MICHLIN

Université de Paris IV-Sorbonne

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Awkward, Michael. “Roadblocks and Relatives: Critical Revision in Toni Morrison’s

The Bluest Eye.” Ed. Nellie McKay. Critical Essays on Toni Morrison. Boston:

GK Hall, 1988. 57-67.

Bambara, Toni Cade. Gorilla, My Love. [1972]. New York: Random House, 1992.

Bass, Ellen and Laura Davis. The Courage to Heal: A Guide for Women Survivors of

Child Sexual Abuse. [1988]. New York: Harper, 1994.

Bouson, J. Brooks. “Quiet As It’s Kept”: Shame, Trauma, and Race in the Novels of

Toni Morrison. Albany: State U of New York P, 2000.

Everett, Percival. Erasure. [2001]. London: Faber, 2003.

Feng, Pin-Chia. The Female Bildungsroman by Toni Morrison and Maxine Hong

Kingston. New York: Peter Lang, 1998.

Freyd, Jennifer J. Betrayal Trauma. Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard UP, 1996.

EA 2-2006.indb 184 17/07/06 12:20:10

NARRATIVE AS EMPOWERMENT IN SAPPHIRE’ PUSH 185

Gates, Henry Louis Jr. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of Afro-American Literary

Criticism. New York: Oxford UP, 1988.

—. Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the “Racial” Self. [1987]. New York: Oxford

UP, 1989.

— and Antony Appiah, eds. Toni Morrison. Critical Perspectives, Past and Present.

New York: Amistad, 1993.

Gibson, Donald. “Text and Countertext in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye”. In

Literature Interpretation Theory 1-2 (Dec 1989): 19-32.

Heller, Janet Ruth. “Toni Cade Bambara’s use of African American Vernacular

English in ‘The Lesson’”. Style. DeKalb: Northern Illinois U, 37, 3 (Fall 2003):

279-93.

Herman, Judith. Trauma and Recovery. [1992]. New York: Basic Books, 1997.

Knauer, Sandra. Recovering from Sexual Abuse, Addictions, and Compulsive

Behaviors:”Numb” Survivors. New York: Haworth P, 2002.

Miller, Laura. “But Enough About Us: Incest and the Memorization of American

Fiction”. http://archive.salon.com/com/special/tenth/2005/11/05/95_96/index.html

Mitchell, Angelyn. The Freedom to Remember: Narrative, Slavery and Gender in

Contemporary Black Women’s Fiction. Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2002.

Morrison, Toni. The Bluest Eye. [1970]. London: Vintage, 1999.

Muther, Elizabeth. “Bambara’s Feisty Girls: Resistance Narratives in Gorilla, My

Love”. African American Review. Terre Haute: Indiana State U, 36, 3) (Fall

2002): 447-59.

Owen, Sally. “Sapphire’s Push Comes to Shove”.

http://www.echonyc.com/~onissues/f96sapphire.html

Queer Press Collective, ed. Loving in Fear: Lesbian and Gay Survivors of Childhood

Sexual Abuse. [1991]. Toronto: Queer P, 1992.

Rampersad, Arnold. The Life of Langston Hughes. Vol. 1: 1902-1941. I, Too, Sing

America. [1986]. New York: Oxford UP, 1988.

Sapphire. Push. [1996]. New York: Vintage, 1997.

—. American Dreams. [1988]. New York: Vintage, 1996.

Shaughnessy, Brenda. “The Sexual Poetics of Sapphire”. Village Voice Literary

Supplement. October 1999.

http://www.villagevoice.com/vls/164/shaughnessy.shtml

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

© Klincksieck | Téléchargé le 07/01/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 81.201.6.248)

Walker, Alice. The Color Purple. [1983]. London: Women’s P, 1986.

Interviews

Casey, Darius. “Sapphire Produces a Gem”. A&E, July 19, 1996.

http://www.daily.umn.edu/ae/Print/ISSUE38/special3.html

Le Clair, Thomas. “‘The Language Must Not Sweat’: A Conversation with Toni

Morrison.” New Republic 184 (March 1981). Gates and Appiah, 369-77.

Miller, Lisa. “Sapphire Interviewed”. Urban Desires, 1996.

http://desires.com/2.4/Word/Reviews/Docs/sapphire.html

Win, Shein Maw. “The Uncompromising Issue. Seeking Hope, Sharing Insight with

author Sapphire.” http://www.cometmagazine.net/comet2/sapphire.html

EA 2-2006.indb 185 17/07/06 12:20:12

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Eger 244 0593Document24 pagesEger 244 0593irlandik221Pas encore d'évaluation

- Litt 144 0081Document21 pagesLitt 144 0081Mwami JosePas encore d'évaluation

- Femmes Et Livres Pornographiques de L Emancipation Des Femmes Au Sein Des Textes Pornographiques Du Siecle Des Lumieres 1700 1789Document140 pagesFemmes Et Livres Pornographiques de L Emancipation Des Femmes Au Sein Des Textes Pornographiques Du Siecle Des Lumieres 1700 1789Abdoul karim YayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sur Le Caractere Hispanique de Don JuanDocument13 pagesSur Le Caractere Hispanique de Don JuanD'AGOSTINPas encore d'évaluation

- L'homme Selon Marx - 4 - L'anthropologie de MarxDocument67 pagesL'homme Selon Marx - 4 - L'anthropologie de MarxrazafindrakotoPas encore d'évaluation

- MonthérlantDocument20 pagesMonthérlantAnonymous Vh6KTNceosPas encore d'évaluation

- La Critique Dramatique À L'épreuve de La Polémique. L'abbé D'aubignac Et La Querelle de SophonisbeDocument13 pagesLa Critique Dramatique À L'épreuve de La Polémique. L'abbé D'aubignac Et La Querelle de SophonisbeBenedetta BartoliniPas encore d'évaluation

- Wang Luxuan m2 Rech 2013 DumDocument118 pagesWang Luxuan m2 Rech 2013 DumnicetchiPas encore d'évaluation

- Rom 143 0069Document10 pagesRom 143 0069Bakaile Bayang BorisPas encore d'évaluation

- D'un Lecteur (Modèle) : Verre Cassé D'alain Mabanckou À La RechercheDocument10 pagesD'un Lecteur (Modèle) : Verre Cassé D'alain Mabanckou À La RechercheZïnbē MėäãmërPas encore d'évaluation

- Litteratures AfricainesDocument383 pagesLitteratures AfricainesChristian KOUTONPas encore d'évaluation

- La LitteratureDocument10 pagesLa Litteraturemohamed dagngoPas encore d'évaluation

- Afco 241 0043Document12 pagesAfco 241 0043KOMBAPas encore d'évaluation

- Konan Richmond 2012 Ed520Document466 pagesKonan Richmond 2012 Ed520Abdal ArtPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis La Malédiction LittéraireDocument494 pagesThesis La Malédiction LittéraireGiovanny SalasPas encore d'évaluation

- Étude Stylistique de La Marginalisation Dans Le Rap Francophone: Le Cas Du Jeune LCDocument65 pagesÉtude Stylistique de La Marginalisation Dans Le Rap Francophone: Le Cas Du Jeune LCNathan ViguierPas encore d'évaluation

- Les Fanfictions Sur Internet - Les Fanfictions Sur InternetDocument4 pagesLes Fanfictions Sur Internet - Les Fanfictions Sur InternetRicardo RogersPas encore d'évaluation

- Titre. L Image Et L Identité Féminines Entre Mère Et Patrie Dans La Civilisation, Ma Mère!... de Driss ChraïbiDocument105 pagesTitre. L Image Et L Identité Féminines Entre Mère Et Patrie Dans La Civilisation, Ma Mère!... de Driss ChraïbiMounir Oussikoum100% (3)

- Aphi 663 0603 PDFDocument32 pagesAphi 663 0603 PDFبلقصير مصطفىPas encore d'évaluation

- Filliations Textuelles, Nationales Et Culturelles - Les Genres Littéraires en Contexte PostcolonialDocument117 pagesFilliations Textuelles, Nationales Et Culturelles - Les Genres Littéraires en Contexte PostcolonialCílio LindembergPas encore d'évaluation

- Rom 162 0103Document11 pagesRom 162 0103Hamza٨٣٩٣Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edb 035 0031Document22 pagesEdb 035 0031Ayoub StraightPas encore d'évaluation

- Bulletin D'histoire Des ÉsotérismesDocument34 pagesBulletin D'histoire Des ÉsotérismesMarco SpottiPas encore d'évaluation

- V 405 S 974 FDocument254 pagesV 405 S 974 Ffeyzakouanda26Pas encore d'évaluation

- CasablancaDocument27 pagesCasablancaCarol NakaoskiPas encore d'évaluation

- L'alliance de La Liettérature Et de La PsychanalyseDocument10 pagesL'alliance de La Liettérature Et de La PsychanalyseGabriellePas encore d'évaluation

- Devereux Et Le Mythe Cohe - 190 - 0081Document5 pagesDevereux Et Le Mythe Cohe - 190 - 0081Joël BernatPas encore d'évaluation

- Les Archives de Fanfictions Sur InternetDocument90 pagesLes Archives de Fanfictions Sur InternetjetemmerdePas encore d'évaluation

- Depetria Crossing Readings On Mysticism AlejandraDocument22 pagesDepetria Crossing Readings On Mysticism AlejandrajmbonecPas encore d'évaluation

- Arss 144 0033Document15 pagesArss 144 0033Paulo Rodrigo SoaresPas encore d'évaluation

- Histoires Littéraires Et Littératures AfricainesDocument14 pagesHistoires Littéraires Et Littératures Africainesdavid cumbanePas encore d'évaluation

- Lett 061 30Document7 pagesLett 061 30Zakaria AzizPas encore d'évaluation

- Race Et Colonialité Du Pouvoir - ANÍBAL QUIJANODocument9 pagesRace Et Colonialité Du Pouvoir - ANÍBAL QUIJANOJosé luis ChavezPas encore d'évaluation

- Elsa Courant - Renan, Müller and Comparative MythologyDocument18 pagesElsa Courant - Renan, Müller and Comparative MythologySublime PortePas encore d'évaluation

- Un Nouvel Élargissement Du Corpus Littéraire en Malgache Moderne: Les Traductions Du CoranDocument474 pagesUn Nouvel Élargissement Du Corpus Littéraire en Malgache Moderne: Les Traductions Du CoranEly Jhons Ratsihoarana VELOTONGAPas encore d'évaluation

- Fil D'ariane 3eDocument300 pagesFil D'ariane 3esylvie100% (2)

- Mettre en Biblio - KALIFA - Les Historiens Français Et Le PopualireDocument7 pagesMettre en Biblio - KALIFA - Les Historiens Français Et Le PopualireValemoralesVPas encore d'évaluation

- Lehalle, Béatrice - SUBLIMATION ET CRISE DU MILIEU DE LA VIEDocument8 pagesLehalle, Béatrice - SUBLIMATION ET CRISE DU MILIEU DE LA VIEFelipeHenriquezRuzPas encore d'évaluation

- Dio 203 0139Document8 pagesDio 203 0139Amina KannanPas encore d'évaluation

- Un Travail de Compilation Sur Les Superstitions Populaires Des XVII Et Xviii Siècles: L'histoire DesDocument180 pagesUn Travail de Compilation Sur Les Superstitions Populaires Des XVII Et Xviii Siècles: L'histoire DesAnoventia OrxswixyPas encore d'évaluation

- Marc Ferro (Éd.) Le Livre Noir Du ColonialismeDocument12 pagesMarc Ferro (Éd.) Le Livre Noir Du ColonialismeDonovan Thurup100% (2)

- History and Fiction As Narrative in The Novels of Salman RushdieDocument124 pagesHistory and Fiction As Narrative in The Novels of Salman Rushdievivek mishraPas encore d'évaluation

- Annie Ernaux Escritura y Humillacion PDFDocument681 pagesAnnie Ernaux Escritura y Humillacion PDFAdam HillPas encore d'évaluation

- La Pensee Feministe Noire Patricia Hill Collins Download 2024 Full ChapterDocument47 pagesLa Pensee Feministe Noire Patricia Hill Collins Download 2024 Full Chapterphyllis.hunter266100% (10)

- Marie-Laure Ryan - FRONTIÈRE DE LA FICTION - DIGITALE OU ANALOG...Document16 pagesMarie-Laure Ryan - FRONTIÈRE DE LA FICTION - DIGITALE OU ANALOG...alienor.mitsunePas encore d'évaluation

- Livre-Cusimano, Christophe - Sens en Mouvement Études de Sémantique InterprétativeDocument139 pagesLivre-Cusimano, Christophe - Sens en Mouvement Études de Sémantique InterprétativeaksilPas encore d'évaluation

- Articie Bouts de Bois de DieuDocument14 pagesArticie Bouts de Bois de DieuMassiwokPas encore d'évaluation

- PDF Ang Tle LP U16Document17 pagesPDF Ang Tle LP U16Steven DongPas encore d'évaluation

- Ibn Taymiyyas Theory of Knowledge PDFDocument105 pagesIbn Taymiyyas Theory of Knowledge PDFwasimsnw100% (1)

- Contes Et Récits Du Maghreb Territoires de L'imaginaire Et Enjeux SocioculturelsDocument423 pagesContes Et Récits Du Maghreb Territoires de L'imaginaire Et Enjeux Socioculturelsloubna bleuPas encore d'évaluation

- Émile Zola - Une Page D'amourDocument184 pagesÉmile Zola - Une Page D'amourphilooPas encore d'évaluation

- Article 1 MbembeDocument29 pagesArticle 1 MbembejuliettegihoulPas encore d'évaluation

- Document Sur Espece FabulatriceDocument144 pagesDocument Sur Espece FabulatriceKaeMPas encore d'évaluation

- TFG Clément Moreno CaronDocument80 pagesTFG Clément Moreno CaronLudmila AquinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Literatura e Texto EletronicoDocument23 pagesLiteratura e Texto EletronicoLuciane SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Les Secrets Des Sorciers Noirs de Vincent Ouattara-2Document14 pagesLes Secrets Des Sorciers Noirs de Vincent Ouattara-2Amadé ZoromPas encore d'évaluation

- Licla 085 0041Document27 pagesLicla 085 0041Mouha SyllaPas encore d'évaluation

- Essais de Palingénésie Sociale. Orphée / (Par P.-S. Ballanche)Document547 pagesEssais de Palingénésie Sociale. Orphée / (Par P.-S. Ballanche)Bailey FensomPas encore d'évaluation

- Alter ego: Le genre superhéroïque dans la BD au Québec (1968-1995)D'EverandAlter ego: Le genre superhéroïque dans la BD au Québec (1968-1995)Pas encore d'évaluation

- CSTC-2009-Bétons Ultra Hautes PerformancesDocument8 pagesCSTC-2009-Bétons Ultra Hautes PerformancesJoseph KanaanPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Muse 774083Document36 pagesProject Muse 774083rorowetzel02330Pas encore d'évaluation

- Un Guide Pour Limplantation Dglises Melvin L HodgesDocument36 pagesUn Guide Pour Limplantation Dglises Melvin L HodgesJean Gardy Dorimain100% (2)

- Secteur BTP Au MarocDocument4 pagesSecteur BTP Au Marocayoub ghouatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Scénario ContratDocument10 pagesScénario ContratalimadPas encore d'évaluation

- Synthese Droit de La FamilleDocument15 pagesSynthese Droit de La FamilleDEHPas encore d'évaluation

- 1502 Le Cacao Dans Les Coutumes Populaires Du Venezuela J VellardDocument9 pages1502 Le Cacao Dans Les Coutumes Populaires Du Venezuela J VellardElisee princePas encore d'évaluation

- Éléphant de Savane D'afriqueDocument6 pagesÉléphant de Savane D'afriqueOrcel GenesysPas encore d'évaluation

- Des Députés Européens de 13 Pays Écrivent À La FIFA Pour L'alerter Contre L'inclusion de Stades Dans Les Territoires Occupés Du Sahara OccidentalDocument2 pagesDes Députés Européens de 13 Pays Écrivent À La FIFA Pour L'alerter Contre L'inclusion de Stades Dans Les Territoires Occupés Du Sahara Occidentalporunsaharalibre.orgPas encore d'évaluation

- Vocabolario, Grammatica e AttivitáDocument112 pagesVocabolario, Grammatica e AttivitáMihaela BajenaruPas encore d'évaluation

- Denis Essoh-CVDocument2 pagesDenis Essoh-CVJoel TétchiPas encore d'évaluation

- Programme Classe de CM1Document22 pagesProgramme Classe de CM1Frederic von LothringenPas encore d'évaluation

- Unite de Fabrication de Couvercle en Beton Dossier TechniqueDocument6 pagesUnite de Fabrication de Couvercle en Beton Dossier TechniqueHoussamHannad50% (2)

- OntologieDocument2 pagesOntologieleilalilyana950Pas encore d'évaluation

- Manuel de Fonctionnement Des ComptesDocument254 pagesManuel de Fonctionnement Des Comptesderbal.abdennacerPas encore d'évaluation

- Fiche 1Document2 pagesFiche 1Youssef AsliPas encore d'évaluation

- 0 - Efm Techniques de VenteDocument2 pages0 - Efm Techniques de VentebusinessmanidouarPas encore d'évaluation

- L'occupation Italienne Du Sud de La FranceDocument5 pagesL'occupation Italienne Du Sud de La FrancePierre AbramoviciPas encore d'évaluation

- Omci - Liste Des Documents Requis Pour Le PartenariatDocument7 pagesOmci - Liste Des Documents Requis Pour Le PartenariatDavid nyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Programme de Messe 5eme Dimanche de Paques A PDFDocument2 pagesProgramme de Messe 5eme Dimanche de Paques A PDFlinda nyliPas encore d'évaluation

- Fi Pathologie Batiment b11 Desordres Structurels Constructions BoisDocument2 pagesFi Pathologie Batiment b11 Desordres Structurels Constructions BoisEL Mehdi AL HYANPas encore d'évaluation

- Des Jardins Originaux Dans Nos VillesDocument1 pageDes Jardins Originaux Dans Nos Villesmoussa0001Pas encore d'évaluation

- La Religion de LislamDocument10 pagesLa Religion de LislamgilmarPas encore d'évaluation

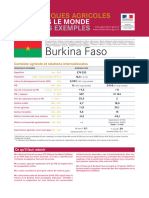

- Fichepays2014 Burkina Faso - Cle499519Document6 pagesFichepays2014 Burkina Faso - Cle499519orianechabossou2021Pas encore d'évaluation

- Memoire Vu - Adikpi observationKOKOLOKODocument22 pagesMemoire Vu - Adikpi observationKOKOLOKOkomi sewonuPas encore d'évaluation

- La Révolution de La Finance - Tome 2 by André Lévy-LangDocument184 pagesLa Révolution de La Finance - Tome 2 by André Lévy-LangGuillaume FLOUX (Théma)Pas encore d'évaluation

- INTRODUCTIONDocument4 pagesINTRODUCTIONAbraham SchekinaPas encore d'évaluation

- F - Chapitre 6Document26 pagesF - Chapitre 6Michel BruleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Manuel Atelier Boite Vitesse FiatIvecoDocument58 pagesManuel Atelier Boite Vitesse FiatIvecojuanPas encore d'évaluation

- Évaluation: CLASSE: Première Voie: ENSEIGNEMENT: Histoire-Géographie Durée de L'Épreuve: 2HDocument4 pagesÉvaluation: CLASSE: Première Voie: ENSEIGNEMENT: Histoire-Géographie Durée de L'Épreuve: 2HALAAPas encore d'évaluation