Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Eufor 371 0026

Eufor 371 0026

Transféré par

Thanh ThảoTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Eufor 371 0026

Eufor 371 0026

Transféré par

Thanh ThảoDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

‘Lost in transition:' EU Foreign Policy and the European

Neighbourhood Policy Post-Arab Spring

Federica Bicchi

Dans L'Europe en Formation 2014/1 (n° 371), pages 26 à 40

Éditions Centre international de formation européenne

ISSN 0014-2808

ISBN 9782855051932

DOI 10.3917/eufor.371.0026

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

Article disponible en ligne à l’adresse

https://www.cairn.info/revue-l-europe-en-formation-2014-1-page-26.htm

Découvrir le sommaire de ce numéro, suivre la revue par email, s’abonner...

Flashez ce QR Code pour accéder à la page de ce numéro sur Cairn.info.

Distribution électronique Cairn.info pour Centre international de formation européenne.

La reproduction ou représentation de cet article, notamment par photocopie, n'est autorisée que dans les limites des conditions générales d'utilisation du site ou, le

cas échéant, des conditions générales de la licence souscrite par votre établissement. Toute autre reproduction ou représentation, en tout ou partie, sous quelque

forme et de quelque manière que ce soit, est interdite sauf accord préalable et écrit de l'éditeur, en dehors des cas prévus par la législation en vigueur en France. Il est

précisé que son stockage dans une base de données est également interdit.

‘Lost in transition:’ EU Foreign Policy and the

European Neighbourhood Policy Post-Arab

Spring

Federica Bicchi

Federica Bicchi is Associate Professor in International Relations of Europe in the Department

of International Relations, London School of Economics. Her research interests include EU

foreign policy towards its Southern neighbourhood, on which she has published inter alia

European Foreign Policy Making towards the Mediterranean (Palgrave, 2007), as well as the

role of information exchanges within the EU foreign policy system and within the European

External Action Service in particular.

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

Introduction

This article aims to assess the response of the European Union to the Arab up-

risings, by focusing on the Southern dimension of the European Neighbourhood

Policy (ENP). The Arab uprisings, or Arab Spring, have created a tremendous stir

in the Arab world and the potential for change remains, despite the number of

negative developments that have occurred since.1 What has been the response of

the European Union (EU)? How has the bloc composed of 27 (28 since the 2013

accession of Croatia) states addressed the tumultuous changes in its Southern

neighbours? As this article will show, the response has brought to the fore the

extent to which the EU vision for the Mediterranean has faded. Confronted with

the upheaval in its Southern neighbours’ domestic politics, the EU has behaved

as an irrelevant power2 and it has not been able to provide an independent input.

In fact, the EU has predominantly reacted to events due to its limited capacities

1. Hamid Dabashi, The Arab Spring: The End of Postcolonialism, (London/New York: Palgrave/Zed Books 2012).

Katerina Dalacoura, “The 2011 uprisings in the Arab Middle East: political change and geopolitical implica-

tions.” International Affairs 88 (1), (2012): 63-79; Asef Bayat, “Revolution in Bad Times,” New Left Review (80),

(2013): 47-60; Fawaz A. Gerges, The New Middle East. Protest and Revolution in the Arab World, (New York:

Cambridge University Press 2014).

2. Federica Bicchi, Europe and the Arab Uprisings: The Irrelevant Power? The New Middle East. Protest and

Revolution in the Arab World. F. Gerges. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 26 09/09/2014 22:32

EU Foreign Policy and the European Neighbourhood Policy Post-Arab Spring 27

for engagement with its Southern neighbours. In political terms, the EU response

and its capacity to positively contribute to political change in the Arab world

have been ‘lost in transition,’ i.e. in the political transition that occurred in the

EU Southern neighbourhood.

This argument will be developed by focusing on the Southern dimension of

the ENP, which has been arguably the main vehicle of the EU response.3 Two as-

pects will be analysed. First, the article will look at the slow but relentless decline

of regionalism as an EU foreign policy goal. Already before the Arab Spring, the

EU had abandoned any attempt at region-building in the Mediterranean. As the

Euro-Mediterranean Partnership gave way to the ENP, the emphasis shifted from

regionalism to bilateralism. The increasing emphasis on the latter, however, has

severely constrained the political role the EU could play when faced with the

fragmentation created by the Arab uprisings. With the partial demise of the ‘Arab

Presidents for life,’4 Europe’s Southern neighbourhood came to include countries

barely touched by the uprisings as well as countries profoundly and dramatically

affected. Bilateralism became stretched beyond limit. Second, the article will ad-

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

dress EU foreign aid to Arab Mediterranean countries. The ENP is accompanied

by the ENP Instrument (ENPI), which is an EU budget line devoted to support

economic and political transitions in the neighbouring countries. The type of

transition envisaged centres on economic and (to a much more limited extent)

political liberalisation. However, an analysis of the financial flows from the EU

to the Arab Mediterranean countries reveals that while more has been promised,

less has been delivered, as the disbursement rate has significantly worsened since

2011. Both the decline of region-building and the worsening of financial engage-

ment in the Southern Mediterranean signal how the EU’s efforts have been ‘lost

in transition.’

The article will first focus on the decline of region-building, by addressing

how the rise of the ENP has had positive consequences for specific countries but

also entailed the loss of a strategic vision for the region. It will then examine how

the EU financial contributions to Arab Mediterranean countries have changed in

response to the Arab uprisings, by providing aggregated data as well as data by

country.

3. Richard Gillespie, The European Neighbourhood Policy and the Challenge of the Mediterranean Southern

rim. The EU’s Foreign Policy: What Kind of Power and Diplomatic Action? M. Telò and F. Ponjaert, (Farnham,

Ashgate 2013).

4. Roger Owen, The rise and Fall of Arab Presidents for Life Cambridge (MA)/London, (Harvard University

Press 2012).

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 27 09/09/2014 22:32

28 Federica Bicchi

The drift away from a European vision for the Mediterranean: the decline of

region-building

The rise of the ENP as the main instrument for EU foreign relations with its

Southern neighbours has entailed a shift of emphasis from region-building to bi-

lateralism. While some Mediterranean countries thrived outside the constrictions

of the regional framework, the shift left the Europeans without a clear vision for

the area. As a consequence, when the Arab spring brought an increased degree of

fragmentation to the Mediterranean, the EU could do little to counter the trend.

While the period 1995-2005 was marked by the centrality of the Euro-Med-

iterranean Partnership, which the EU launched to address its Southern partners,

in the following decade the emphasis turned slowly but relentlessly away from the

multilateral framework of the EMP and towards bilateral relations with Southern

neighbours as framed in the ENP. The change of language was thus revealing of

the shift in policy.

The region-building strategy of the EU has a long history.5 It started with the

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

Global Mediterranean Policy in 1972, when member states ‘invented’ the Medi-

terranean as a political area that was homogenous enough to justify addressing all

parts in the same way. The GMP consisted in nearly identical, parallel bilateral

channels, which however lacked a multilateral framework. One of the main nov-

elties of the EMP (if not the main one) was instead the degree of multilateralism

and regionalism embedded in the endeavour, as testified by the multilateral set-

ting it created. The EMP set out to ‘construct’ the Mediterranean, by establishing

a semi-permanent, multilateral dialogue on a very broad agenda, spelled out in

the three baskets of the Barcelona Declaration. Faced with a number of perceived

security issues, the EU addressed them by region-building, in the form of regional

dialogues, rather than by intensifying intra-European security cooperation.6 The

extent to which this was done with the final goal to create a common Euro-Med-

iterranean region, rather than a separate non-European Mediterranean region is a

matter of discussion.7 The nature of the relationship often corresponded “more to

a soft form of hegemony than to a partnership,”8 largely reflecting the imbalance in

5. Federica Bicchi, European Foreign Policy Making toward the Mediterranean, (New York/Basingstoke: Palgrave

Macmillan 2007).

6. Emanuel Adler and Beverly Crawford Normative Power: The European Practice of Region Building and the

Case of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (EMP). The Convergence of Civilizations. Constructing the Mediter-

ranean Region, Emanuel Adler, Federica Bicchi, Beverly Crawford and Raffaella Del Sarto. (Toronto: University

of Toronto Press 2006).

7. Michelle Pace, The Politics of Regional Identity: Meddling with the Mediterranean, (London and

New York: Routledge 2006.)

8.Eric Philippart, “The Euro-Mediterranean Partnership: a critical evaluation of an ambitious scheme,”

European Foreign Affairs Review, 8, (2003) pp. 201–220.

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 28 09/09/2014 22:32

EU Foreign Policy and the European Neighbourhood Policy Post-Arab Spring 29

terms of economic and political power.9 Nevertheless, the institutionalization of

the EMP’s multilateral dimension was an undeniable achievement in comparison

with the previous 20+ years of Euro-Mediterranean relations. As it turned out,

it was a parenthesis in the long history of Euro-Mediterranean relations, during

which bilateral relations were subordinated to the regional agenda.

The ENP reversed this situation and brought bilateralism to the fore, allow-

ing countries with a potentially broader and richer agenda to develop it much

more easily. The ENP reintroduced a strong degree of bilateralism,10 which could

be seen in a number of ways: the ‘regatta approach,’ the granting of ‘advanced

status’ to selected partners and the negotiation of agreements in addition to the

EuroMed Association Agreements. All signalled that the relationship between the

multilateral dialogue among participants on both shores of the Mediterranean

and the agenda for bilateral relations was reversed. Rather than the multilateral

dialogue setting the themes to be then adopted and adapted in bilateral relations,

bilateral relations were to explore avenues that could not be addressed at the

multilateral level.11

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

This allowed willing countries to tremendously expand the agenda for their

cooperation with the EU, while others lagged behind. Morocco is a case in point,

and a similar case could be made for Israel. The differentiated approach of the

ENP is “precisely what Morocco has asked for”12 and it has led to an increase in

new areas of cooperation, such as aviation. The EU-Morocco aviation agreement,

signed in 2006, is a case in point. Not only it addressed a broad number of

regulatory issues, including flight safety and competition, but also and most im-

portantly it lifted capacity restrictions between the EU and Morocco. Traditional

and low cost airlines have been quick to benefit from the opportunity and as a

consequence, indicators of traffic with EU countries increased exponentially. The

number of flights tripled from ca. 200.000 in 2005 to nearly 600.000 by 2010,

whereas the number of international tourist arrivals doubled from 4.27 million

in 2000 to 9.34 million13 in 2011,14 thus contributing to Morocco’s official objec-

tive of 10 million tourists by 2010 and 20 million tourists by 2020. This has had

9. cf. Patrick Holden, In Search of Structural Power: EU aid policy as a global political instrument, (Ashgate Pub-

lishing, Ltd 2009).

10. Raffaella Del Sarto & Tobias Schumacher, “From the EMP to ENP: what’s at stake with the European

Neighbourhood Policy towards the southern Mediterranean?” European Foreign Affairs Review, 10 (1), (2005)

pp. 17–38.

11. Only one indication remained of the ambitious plan for a Euro-Mediterranean free trade area, namely the

pan-Euro-Mediterranean protocol on rules of origins, which does contribute to the original goal, but in a much

less demanding way.

12. Country Report Morocco 2004, p. 5.

13. This includes also Moroccans resident abroad, though.

14. Frédéric Dobruszkes and Véronique Mondou “Aviation liberalization as a means to promote international

tourism: The EU-Morocco case,” Journal of Air Transport Management 29 (2013): 23-34.

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 29 09/09/2014 22:32

30 Federica Bicchi

a tremendous impact on the cities such as Marrakesh15 and more generally on the

tourist economy. The hotel industry in Morocco has grown on average over the

period 2001-2011 by 14%,16 while the overall contribution to Moroccan GDP is

a solid 9%, despite the 2008 crisis taking a small toll.17 As Morocco still employs

nearly 40% of its workforce in agriculture, which however represents only 15%

of the total value added of the economy,18 a path to diversification is seen as a

path to modernization, despite the related social tensions.

The Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) represented a further step away from

regionalism.19 A key aim of UfM has been to promote projects among groups

of willing countries, and sub-regionalism in particular. While possibly a sign of

pragmatism, the importance assigned to the sub-regional level implicitly recog-

nized that the regional level could not deliver. Its institutionalization and the

emphasis on coalitions of the willing rely on functional complementarities or

overlapping visions more than it promotes ambitious plans to create common

political projects out of dissent. In short, it downsizes the political significance of

the EU foreign policy toward the area, although it also introduces a degree of real-

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

ism. The increase in the number of participants to 43 states further contributed

to the dilution of regionalism.

The UfM fell prey to the Arab-Israeli conflict, which came to dominate meet-

ings pre-Arab spring. 2010 was emblematic in this respect. Three ministerial

sectorial meetings (devoted to water, tourism and agriculture) were hampered

because of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Despite having reached a consensus on the

working programme, the ministerial meeting on water failed to issue a final dec-

laration because participants could not agree on how to refer to the ‘occupied

territories.’ Similarly, the difficulties in organizing a second summit of heads of

state and governments soon became overwhelming and Spain, which held the

European presidency in the second half of 2010, had to accept a postponement.

In the end, once the Arab uprisings started, both plans for the ministerial foreign

affairs meeting and the summit were shelved indefinitely.

The Arab spring further increased the differentiation among countries of the

Southern shore. The Arab world was partially redrawn and the range of varia-

tion increased. On the one end of the spectrum, Algeria, Jordan, Morocco and

15. Nicolai Scherle, Tourism, neoliberal policy and competitiveness in the developing world. The case of the Master

Plan of Marrakech. Political Economy of Tourism. A Critical Perspective. J. Mosedal. (Abingdon/New Your: Rout-

ledge 2011). pp. 217–24.

16. Eurostat European Commission, Pocketbook on Euro-Mediterranean statistic, (Luxembourg, Publications

Office of the European Union 2013).

17. World Travel & Tourism Council, Travel & Tourism Economic Impact 2012. Morocco. (London, 2012)., p. 3

18. Eurostat European Commission Pocketbook on Euro-Mediterranean statistics, (Luxembourg, Publications

Office of the European Union 2013).

19. Federica Bicchi “The Union for the Mediterranean, or the Changing Context of Euro-Mediterranean Rela-

tions,” Mediterranean Politics, 16 (1) (2011): 3-19.

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 30 09/09/2014 22:32

EU Foreign Policy and the European Neighbourhood Policy Post-Arab Spring 31

Palestine underwent changes, none of which however really upset the nature of

the regime in place.20 At the other end of the spectrum, Libya and Syria not only

witnessed deep civil wars (and in the case of Libya an intervention from Western

countries to topple the regime), but also in their aftermaths came to include areas

of limited statehood, as the authoritarian grasp of Gaddafi and Assad relented

and other more local and less organised forms of authority filled the gap.21 Tunisia

and Egypt instead underwent a political transition, which in the case of Tunisia

is more solidly footed in the direction of democracy than in the case of Egypt.22

Lebanon, for its part, has been struggling to keep its domestic balance given the

impact of the civil war in Syria over its own population.

The European response to the Arab spring remained anchored in the ENP,

even though in a ‘revised’ format. Three communications sketched the EU re-

sponse to the crisis. In the first one, A Partnership for Democracy and Shared Pros-

perity with the Southern Mediterranean,23 published in March 2011, the EEAS

and the European Commission presented an ‘incentive-based approach.’ It was

summarised in the motto ‘more for more,’ indicating that more reforms would

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

be repaid with more cooperation and greater support from the EU. Ashton sum-

marised the issues at stake in the communication as the ‘3-Ms’: money, mobility,

and market access. This approach, heralded as a ‘fundamental step change in

the EU’s relationship’ with those partners that commit themselves to reforms,24

offered ‘mobility partnership’ to ease legal migration, an increase in funds, and

more market access through the negotiation of “Deep and Comprehensive Free

Trade Areas,” including, for instance, ‘regulatory convergence.25 The document

was followed by another communication, A New Response to a Changing Neigh-

bourhood, issued in May 2011.26 It elaborated further on the previous one and it

stressed again conditionality as a cornerstone of EU foreign policy: “Increased EU

20. Michael Willis, Politics and power in the Maghreb: Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco from independence to the Arab

Spring, (London: Hurst 2012); Michelle Pace, “An Arab ‘Spring’ of a Different Kind? Resilience and Freedom

in the Case of an Occupied Nation.” Mediterranean Politics 18 (1) (2013): 42-59; Frédéric Volpi, “Algeria versus

the Arab Spring,” Journal of Democracy 24 (3) (2013): 104-115.

21. Mattia Toaldo, “A European agenda to support Libya’s transition,” The European Council on Foreign Re-

lations, 19 May 2014, available at: http://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/a_european_agenda_to_sup-

port_libyas_transition308.

22. Laura Guazzone, “Ennahda Islamists and the Test of Government in Tunisia,” The International Spectator 48

(4) (2013): 30-50; Daniela Pioppi, “Playing with Fire. The Muslim Brotherhood and the Egyptian Leviathan.”

The International Spectator 48 (4) (2013): 51-68.

23. Joint Communication to the European Council, the European Parliament, the Council, the European Eco-

nomic and Social Committee, and the Committee of the Regions, Brussels, 8 March 2011, COM (2011)200

final.

24. Idem, p. 5.

25. Idem, p. 9.

26. Joint Communication to the European Council, the European Parliament, the Council, the European

Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Brussels, 25 May 2011, COM (2011)

303 final.

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 31 09/09/2014 22:32

32 Federica Bicchi

support to its neighbours is conditional.”27 The third one launched a programme

entitled SPRING (Support for Partnership, Reforms and Inclusive Growth) in

September 2011, aimed at supporting democratic transitions, economic growth,

and institution building.

There was nothing really new in these communications, and especially in the

principles they embodied. While additional funds are important (but, as we are

going to see in the next section, hard to come by), the discussion on mobility did

not deliver any significant results and the main tools of the EU have remained

trade and limited aid, coupled with conditionality. The latter, a key EU instru-

ment for linking trade and aid to political developments, saw its role reconfirmed

in the post-Arab Spring context.28

Therefore, with an increased fragmentation on the ground and little attempt

to revive a European vision for the Mediterranean, the initiative has been outside

Europe. The trend towards fragmentation and diversification has further weak-

ened the already feeble attempts of the EU to draw local actors together in some

forms of regional or sub-regional dialogues. The Europeans thus struggled to in-

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

volve Southern neighbours in the management of complex issues, such as Libya,

Syria or Palestine. The UfM has not been able to deliver multilateral meetings

beyond the sectorial level, nor any sub-regional project of political significance.

The bilateral dialogues within the ENP continue, but it is up to the Southern

neighbours to impress the necessary momentum. As EU actors recently acknowl-

edged, “the success of the policy is directly dependent on the ability and commitment

of [Southern] governments to reform and deepen relations with the EU, as well as

on the capacity to explain and gain popular support and adherence to this agenda.”29

The EU has seemingly lost the ability to provide an independent input. It is in

this context that discussions about a possible reform of the ENP have begun to

take place, in order to understand what direction the EU could impress to Euro-

Mediterranean relations.

27. Idem, p. 3.

28. See, e.g., Rosa Balfour, “Changes and Continuities in EU-Mediterranean Relations after the Arab Spring,”

in S. Biscop, R. Balfour and M. Emerson (eds.), Arab Springboard for EU Foreign Policy, Egmont Paper 54,

(2012) pp. 27–35. and Smith, Karen E. (1998), ‘The Use of Political Conditionality in the EU’s Relations with

Third countries: How Effective?’, European Foreign Affairs Review, 3 (2), 253-74.

29. European Commission and High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security

Policy, “Neighbourhood at the Crossroads: Implementation of the European Neighbourhood Policy in 2013”,

Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the Council, the Economic and Social Committee and the

Committee of the Regions, Brussels, 27 March 2014, JOIN (2014) 12 final, p. 2.

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 32 09/09/2014 22:32

EU Foreign Policy and the European Neighbourhood Policy Post-Arab Spring 33

The drift away from engagement on the ground: the financial practice of the

ENP

Given the context highlighted in the previous section, it comes as no surprise

that the EU has allegedly committed more funds to neighbouring Arab countries,

but has in fact spent less than before. The gap between rhetoric and practice

is well captured by the analysis of the financial instrument related to the ENP,

namely the European Neighbourhood Policy Instrument (ENPI), and how it has

been less able than before to engage with Arab countries in the post-Arab spring

context. While aid is always politically motivated,30 it cannot be a substitute for

politics. As this section will show, the EU has increased funds committed to Arab

countries. However, the change is not as substantial as it is often assumed and

certainly not to be taken for granted as often suggested. As EU budget commit-

ments for 2012 and 2013 have increased sharply, disbursements on the contrary

have declined. At a country level, commitments too have not increased uniformly

across the board, with several countries experiencing a less linear development.

Finally, the EU also created a number of new programmes, such as SPRING

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

(Support for partnership, reforms and inclusive growth), on the ENPI budget

line, but it will take time to understand whether they can be actually implement-

ed beyond the commitment stage. The most immediate change in EU funding

practices, therefore, was in the nominal amount of funds available, rather than in

funds effectively spent.

A preliminary proviso is worth noticing here. All budgets of public authori-

ties are generally composed of three sets of figures, covering the same budget en-

tries: 1) a programmed budget, which identifies planned spending; 2) the budget

committed to specific priorities within the programmed budget; 3) the actual

amount disbursed to fund those actions, generally referred to as the outrun. This

is also valid for the EU budget for external relations, which is divided in 1) a pro-

grammed budget, i.e. a general indication of how much the EU will spend, 2) the

budget committed, as expressed in planning documents (such as Annual Action

Programmes, etc.), 3) the actual amount disbursed, i.e. a number of contracts

that lead to the transfer of funds from the EU to the contracted agents. While

1) and 2) are generally referred to in Euro-speak as ‘commitments,’ 3) is instead

indicated as ‘disbursements’ or ‘payments.’

Typically, the three sets of figures never correspond, in the EU budget as else-

where. However, the EU displays a number of EU-specific issues. First, there

can be a considerable time lag between the programming of funds, their com-

mitment and their actual disbursement. The lag can be substantial, as in the case

30. Patrick Holden, In Search of Structural Power: EU aid policy as a global political instrument, (Ashgate Publish-

ing, Ltd 2009).

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 33 09/09/2014 22:32

34 Federica Bicchi

of Financial Protocols signed with Mediterranean countries in the early 1990s,

in pre-Barcelona times, the payments for which were completed only in 2010.31

Moreover, despite a widespread belief to the contrary, the more difficult the task,

the more likely the EU is to under-spend. In the case of the European Initiative /

Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR) in the Mediterranean

countries, the early years of the programme (2001-2005) show an underspending

of 25% of the overall set of commitments, corresponding to over € 3.7 million

earmarked for the promotion of democracy and human rights in the Mediter-

ranean that never reached the ground.32

These considerations are relevant for the case of the ENPI-South, which in-

cludes bilateral, regional and cross-border (sub-regional) co-operation with the

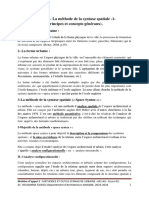

Mediterranean countries. As fig. 1 shows, the Arab uprisings led to an increase

in commitments. Funds committed, which had been increasing at the margins

in previous years, jumped by nearly 50% from 2011 to 2012, a change basically

reconfirmed in 2013. Despite the pressures to reduce the 2014-2020 budget, the

ENP South remained at a relatively high level until 2015, before declining to

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

absorb the budget cuts. This was a victory of the position advocated by the EEAS.

Figure 1: EU budget line 19 08 01 01 (budget 2007-2013, European Neighbourhood

and Partnership financial cooperation with Mediterranean countries) and budget line

21 03 01 (budget 2014-2020, European Neighbourhood Instrument – Supporting co-

operation with Mediterranean countries), (million €). These budget lines do not include

expenditures on administrative management.

Source: EU budget, various years, available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/budget/www/index-en.htm. For 2011-

2012, figures show the actual outrun, whether 2013-2014 are a forecast.

31. Source: EU Budget 2012, part II, p. 822.

32. Federica Bicchi, “Dilemmas of Implementation: EU Democracy Assistance in the Mediterranean.” Democ-

ratization 17 (5) (2010): p. 989.

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 34 09/09/2014 22:32

EU Foreign Policy and the European Neighbourhood Policy Post-Arab Spring 35

At the same time, funds actually paid out to Mediterranean countries have

not followed the same trend. Disbursements decreased in the years following the

inception of the Arab Spring (for a variety of reasons which I will explore later

on). This created a substantial lag between commitments and disbursements,

with more than a € 1.3 billion committed but not spent over 2009-2013 for the

Mediterranean countries.

The unspent margin between commitments and payments is not lost. Rather,

it is spread over a number of years, as the programming authorities define, al-

locate and disburse the funds. The expectations about the period over which this

was going to happen and the ENPI fully brought to fruition have been relatively

loose, though. According to the General Introduction to the 2014 Draft Budget,

the expectation was that it would take ca. 4 years to clear the last ENPI payments

committed in 2013.

These funding practices continued in the following years. In the discussion

about the 2014-2020 budget, member states decided to cut spending for the first

time in EU history, although they did not do so for the Southern neighbourhood

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

for year 2014 (the cut will come into effect in 2015). In terms of spending, the

expectation was that, given the novelty of some of the procedures introduced,

2014 was going to be a particularly ‘low’ year for Mediterranean disbursements,

as new programmes and procedures had to be gradually rolled out.

How can we explain this gap between commitments and disbursements?

Three aspects are worth noting. Most importantly, the political unrest in post-

Arab Spring countries has led to uncertainty and a shrinking absorption capacity

for funds expected to work over a middle-to-long period, such as the ENPI. Sev-

eral factors enter into play here. At times of turmoil, political and administrative

actors are reluctant to undertake application processes unlikely to deliver in the

short term. Moreover, the rapid turnover of actors has left the EU with a limited

set of interlocutors, as political developments have occurred at a faster pace than

the EU aid policy can follow. The political turmoil includes also political priori-

ties, which can shift from one day to the other, thus making extremely difficult to

plan the type of activities the EU excels in.

Second, the increase in funds has been matched by an increase in condition-

ality, i.e. in the number and type of conditions attached to the disbursement of

those funds, often summarised with the motto ‘more for more’ (more reforms

will lead to more concessions). Conditionality entails a substantial element of

discretion, thus in theory hinting to a greater scope for donors—in this case, the

EU—to spend when and where appropriate. The flip side, however, has been that

conditions attached to funds, under the ENPI-South and likely to continue un-

der the ENI-South, have not been met on the ground, thus leaving the EU with

little option but not to spend. The increased conditionality has thus translated in

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 35 09/09/2014 22:32

36 Federica Bicchi

less flexibility in the use of funds, and ultimately in less funds being spent. While

this should reassure the European taxpayer about how funds are (not) spent, it is a

matter for concern in terms of engagement on the ground. It has become difficult

to predict when and where conditions will eventually be met. More generally,

the type of swift reactions that volatile contexts require is not the game at which

the EU excels. The EU has an instrument devoted to stability, which can be used

more promptly. But the engagement enshrined in the ENPI is not suited to crisis

situations.

Finally, as acknowledged in the EU budget accompanying documents, the

programming cycle of the EU entails a time span measured in years for imple-

mentation. Funds earmarked for a specific country, thus appearing on a given

commitment year, can be discussed and tendered in the following year, and dis-

bursed in the year after that, once contracts are finalized. If outsourcing is in-

volved, this might entail a further year. As December tends to be the European

Commission’s preferred month for committing funds (in order not to miss on the

yearly deadline), this can easily stretch the whole process over 3-4 years.33

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

Although this last factor is relevant, the previous two provide the essence of

the explanation for the lag between commitments and disbursements. The down-

wards trend in disbursements is expected to span across more than 3-4 years,

before eventually picking up, whereas the difficulties in matching funds with

activities and conditions are clearly evident across time and countries, despite

contingent and local variation.

While disbursements have been a particularly sore point in the EU policy

towards its Southern neighbours, commitments have not been without prob-

lems either. It is worth exploring how precisely the increase in commitments was

structured for the period 2007-2013. The focus will be on committed bilateral

funds, i.e. funds the EU aims to disburse to single Mediterranean countries in

support of the Association Agreements and related Action Plans. These increased

under the ENPI as a consequence of the Arab Spring, as shown graphically in

Figure 2 and numerically in Table 1, beginning from 2012. The increase at a time

of economic crisis has been generous but, as we are going to see, unevenly spread

across the board.

Commitments were unevenly spread across Arab countries. Egypt and Leba-

non experienced the same ‘slump cum eventual increase’ trend. Funds to Egypt

slumped to € 92 million in 2011 from € 192 million in 2010, before bouncing

to € 250 million in 2012, while Lebanon reached € 33 million in 2011, down

from € 44 million, before climbing to € 92 million. Jordan and Tunisia were

instead the early risers. Both experienced already in 2011 an increase in funding

33. cf. Federica Bicchi, “Dilemmas of Implementation: EU Democracy Assistance in the Mediterranean.” De-

mocratization 17 (5) (2010).: 976-996.

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 36 09/09/2014 22:32

EU Foreign Policy and the European Neighbourhood Policy Post-Arab Spring 37

Figure 2: Bilateral commitments under ENPI (million €)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

Source: Implementation of the ENP in 2012, Statistical Annex, SWD (2013) 87 final, Brussels 20.3.2013;

Implementation of the ENP in 2013, Statistical Annex, SWD (2014) 98 final, Brussels 27.3.2014. 2F

Table 1: Bilateral commitments under ENPI (million €)

ENPI

Algeria Egypt Israel Jordan Lebanon Libya Morocco Syria Tunisia South

Bilateral

2007 57 137 2 62 50 2 190 20 103 623

2008 32.5 149 2 65 50 4 228.7 20 73 624.2

2009 35.6 140 1.5 68 43 0 145 40 77 550.1

2010 59 192 2 70 44 12 158.9 50 77 664.9

2011 58 92 2 111 33 10 156.6 10 130 602.6

2012 84 250 2 110 92 25 207 48.4 130 948.4

Total

2007- 326.1 960 11.5 486 312 53 1086.2 188.4 590 4013,2

2012

Source: Implementation of the ENP in 2012, Statistical Annex, SWD (2013) 87 final, Brussels 20.3.2013;

Implementation of the ENP in 2013, Statistical Annex, SWD (2014) 98 final, Brussels 27.3.2014.

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 37 09/09/2014 22:32

38 Federica Bicchi

over 2010, which represented nearly 60% of increase in the case of Jordan and

nearly 70% of increase in the case of Tunisia. Only Tunisia continued to grow,

however, whereas Jordan saw programmed funds shrink. While Libya and Syria

were the new comers (and funds for Syria in 2013 considerably swelled to care

for Syrian refugees), Morocco was the apparent loser of the game, until a big pot

of money was expected to be allocated at the end of 2013. In fact, the overall

amount of funds Morocco has received under the ENPI is unparalleled once put

in the context of its population. Despite having a population that is less than half

that of Egypt (ca. 32 million in Morocco, nearly € 80 million in Egypt in 2011)

Morocco has received more funds than Egypt over the period 2007-2012.

Moreover, in response to the Arab uprisings, the EU launched a number of

new programmes, drawing on an expanded ENPI budget line.34 For instance,

the EU created in September 2011 the SPRING programme. The programme

received in 2011 € 65 million, earmarked for Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tuni-

sia. It is from this programme that € 20 million were swiftly allocated (commit-

ted) to Tunisia in the autumn 2011, followed by another € 80 million in 2012.

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

For 2012, the programme was funded with € 350 million, then increased to €

390 million to include also Algeria and Lebanon. SPRING was allocated to the

Arab countries having more directly experienced the uprisings and in need of eco-

nomic development. Israel, Libya, Palestine and Syria were not allocated funds

under this programme. SPRING has aimed to support “democratic transformation

and institution-building” as well as “sustainable and inclusive growth and economic

development.”35 It is meant to provide the EU with a more flexible instrument

than the ENPI funds, which are tied to the Action Plans adopted in the frame-

work of the ENP. Therefore, it constitutes an ‘umbrella’ programme with loose

priorities and loose implementation rules. It is also the main vehicle for the ‘more

for more’ approach enshrined in the EU response to the Arab spring.

Two points stand out here. First, as all financial increases in funds potentially

available in the wake of the Arab spring, SPRING has encountered limitations in

absorption capacity on top of EU reluctance to disburse funds. As a consequence,

the commitments for 2013 have been more restrictive. Second, data available in

relation to SPRING disbursements is very scarce. While it is clear how the funds

should be spent, it is very difficult to retrieve information on whether they have

actually been spent, and on what.

The picture provided by the analysis of the funds on the ENPI for Arab South-

ern neighbours therefore shows that there was a change in the EU discourse on

34. For an overview, see Richard Gillespie, The European Neighbourhood Policy and the Challenge of the

Mediterranean Southern rim. The EU’s Foreign Policy: What Kind of Power and Diplomatic Action? M. Telò and

F. Ponjaert, (Farnham, Ashgate 2013).

35. Commission Implementing Decision, C (2011)6828, Brussels 29/9/2011, p. 1.

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 38 09/09/2014 22:32

EU Foreign Policy and the European Neighbourhood Policy Post-Arab Spring 39

foreign aid towards post Arab spring countries, while a broadened discretionary

power was also embedded in the EU funding post-Arab Spring. Pledges and com-

mitments have abounded, but the disconnect between the premises on which

funds can be disbursed and developments on the ground have made it very dif-

ficult to engage financially in the short term. At the same time, it remains to be

seen whether results in the medium-long term will be any different.

Conclusions

By focusing on the Southern dimension of the ENP, this article has shown two

of the main features in the EU response to the Arab spring. First, the EU has been

hampered in its response by the emphasis the increasing prominence of the ENP

has started to put on bilateralism. As the Arab uprisings led to further political

fragmentation in the area, the EU was not able to use a regional framework to

leverage cooperation in the area and to jointly address challenges in the post-

Arab spring context. Second, the financial instrument of the ENP has not been

able in the short term to substitute for politics. While commitments increased,

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

disbursements decreased in a context in which the priorities set by the EU have

been difficult to achieve given the high social, political and economic volatility.

The long and complex implementation process of EU funds has been ill-suited

in the transition period currently characterising the Arab world. The EU political

input has thus been ‘lost in transition.’

This lack of EU political initiative challenges not only policy makers, but also

the academic scholarship on Euro-Mediterranean relations. As argued by Cava-

torta and Rivetti,36 there is the need to take stock of the literature. In the post-

Arab spring context, it has become crucial not just to show the gap between what

the EU says it does and what it actually does, but also to identify the mechanisms

through which this happens, so as to better understand how to redress the imbal-

ance in political initiative.

Abstract

The article assesses the response of the European Union to the Arab uprisings, by focusing on the South-

ern dimension of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP). It shows that the EU vision for the Mediter-

ranean has faded and it has been lost in the transition that Arab countries have been experiencing. Two

aspects are analysed. First, the article shows the slow but relentless decline of regionalism as an EU foreign

policy goal. The trend started prior to the Arab uprisings and in fact with the launch of the ENP, but the

reliance on bilateralism ended up curtailing the European role as the Arab spring led to more fragmenta-

tion in the area. Second, the article addresses EU foreign aid to Arab Mediterranean countries and shows

that since the inception of the Arab spring the EU has been nominally committing more funds, but actually

disbursing less because of the opening gap between conditions for spending the funds and conditions on

the ground.

36. Francesco Cavatorta and Paola Rivetti “EU-MENA Relations from the Barcelona Process to the Arab Upris-

ings: A New Research Agenda,” Journal of European Integration 36 (6) (2014): 619-625.

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 39 09/09/2014 22:32

40 Federica Bicchi

Résumé

L’article évalue la réponse de l’Union européenne aux soulèvements arabes, en mettant l’accent sur la

dimension méridionale de la Politique Européenne de Voisinage (PEV). Il montre que la vision de l’UE pour

la Méditerranée a décliné et qu’elle s’est perdue dans la transition que les pays arabes ont connue. Deux

aspects sont analysés. Tout d’abord, l’article montre le déclin lent mais continu du régionalisme comme

objectif de politique étrangère de l’UE. Cette tendance a commencé avant les soulèvements arabes et, en

fait, avec le lancement de la PEV, mais l’appui sur le bilatéralisme a fini par réduire le rôle de l’Europe en

même temps que le Printemps arabe menait à une plus grande fragmentation de la région. Deuxième-

ment, l’article aborde l’aide extérieure de l’UE aux pays arabes méditerranéens et montre que depuis le

début du Printemps arabe, même si l’UE a nominalement engagé plus de fonds, elle a en fait déboursé

moins en raison de la distance croissante entre les conditions pour les dépenses des fonds et les conditions

réelles d’application.

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

© Centre international de formation européenne | Téléchargé le 08/10/2023 sur www.cairn.info (IP: 1.54.152.60)

L’Europe en formation nº 371 Printemps 2014 - Spring 2014

EEF 371.indb 40 09/09/2014 22:32

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Corrige Economie-Droit 2de 1re Tle BP - Ed 2020Document289 pagesCorrige Economie-Droit 2de 1re Tle BP - Ed 2020Miroulique Skn100% (2)

- Solution Manual For Security in Computing 5th by PfleegerDocument24 pagesSolution Manual For Security in Computing 5th by Pfleegermichellelewismqdacbxijt100% (43)

- Les Enjeux de La Communication FinancièreDocument6 pagesLes Enjeux de La Communication FinancièreTIZAOUIPas encore d'évaluation

- Manager de Projets InformatiquesDocument44 pagesManager de Projets Informatiquesalexis azizaPas encore d'évaluation

- Eufor 366 0045Document39 pagesEufor 366 0045gauzanneau.ieu2020Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reforming Fiscal Federalism in Europe Where Does The Pendulum SwingDocument42 pagesReforming Fiscal Federalism in Europe Where Does The Pendulum SwingAbdullahKadirPas encore d'évaluation

- What Future For Taxation in The EUDocument10 pagesWhat Future For Taxation in The EUholacomoestasPas encore d'évaluation

- Pe 234 0025Document14 pagesPe 234 0025jeanbulalu0303Pas encore d'évaluation

- Eufor 362 0081Document20 pagesEufor 362 0081pushaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pe 234 0081Document18 pagesPe 234 0081jeanbulalu0303Pas encore d'évaluation

- Passeport2023 24Document38 pagesPasseport2023 24loriedonfack965Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pe 234 0011Document16 pagesPe 234 0011jeanbulalu0303Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pe 051 0035Document14 pagesPe 051 0035René yvesPas encore d'évaluation

- Eufor 364 0265Document24 pagesEufor 364 0265Deng HouPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction À L'archéologie Du SavoirDocument27 pagesIntroduction À L'archéologie Du SavoirrazafindrakotoPas encore d'évaluation

- Rfap 183 0280Document10 pagesRfap 183 0280razandry34Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ref Bachelor MKG Digital 21Document40 pagesRef Bachelor MKG Digital 21gouadfelPas encore d'évaluation

- Amx 058 0061Document16 pagesAmx 058 0061DANIEL WANDERSON FERREIRAPas encore d'évaluation

- Pe 234 0053Document13 pagesPe 234 0053jeanbulalu0303Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pe 234 0067Document16 pagesPe 234 0067jeanbulalu0303100% (1)

- La Médiation CulturelleDocument9 pagesLa Médiation CulturelleZahra BoûPas encore d'évaluation

- Pe 234 0039Document14 pagesPe 234 0039jeanbulalu0303Pas encore d'évaluation

- EUSurvey - SurveyDocument16 pagesEUSurvey - SurveyimenPas encore d'évaluation

- Jie PR1 0107Document30 pagesJie PR1 0107IRINA ALEXANDRA GeorgescuPas encore d'évaluation

- Pe 051 0021Document15 pagesPe 051 0021René yvesPas encore d'évaluation

- La Stratégie en ThéoriesDocument15 pagesLa Stratégie en ThéoriesManuela MPas encore d'évaluation

- Ling 501 0035Document41 pagesLing 501 0035Hakim AjaidiPas encore d'évaluation

- L'Organisation de La Financiarisation LBO - 2018Document34 pagesL'Organisation de La Financiarisation LBO - 2018Manal AFconsultingPas encore d'évaluation

- Dynamique D'innovation TerritoireDocument27 pagesDynamique D'innovation Territoiresmahan اسمهانPas encore d'évaluation

- En Suivant Ce Lien:), en Assurant Une Diffusion La Plus Large PossibleDocument1 pageEn Suivant Ce Lien:), en Assurant Une Diffusion La Plus Large PossibleElie RizkPas encore d'évaluation

- Reseaupolytech GuideCandidatureCampusFranceDocument22 pagesReseaupolytech GuideCandidatureCampusFrancehuguesPas encore d'évaluation

- Guide Des Etudes 2013Document60 pagesGuide Des Etudes 2013vp_etudes_fneoPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Troubles Du Neurodeveloppement EditorialDocument5 pages1 Troubles Du Neurodeveloppement Editorialmarion77chapuisPas encore d'évaluation

- NRP 019 0165Document16 pagesNRP 019 0165gafsiPas encore d'évaluation

- Les États Dans Les Relations InternationalesDocument28 pagesLes États Dans Les Relations InternationalesPvl GuedePas encore d'évaluation

- Nras 048 0007Document5 pagesNras 048 0007Safaa AraibaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cips 065 0013Document14 pagesCips 065 0013Hiba LalaouiPas encore d'évaluation

- Stage Pedeagogique Des Professeurs de FleDocument305 pagesStage Pedeagogique Des Professeurs de FleCorina Ciobanu100% (5)

- Erasmusinternational-2024 FRDocument4 pagesErasmusinternational-2024 FRcaro OunitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Med 157 0097Document15 pagesMed 157 0097bourimn3374Pas encore d'évaluation

- Référentiel MBA ManagementDocument36 pagesRéférentiel MBA ManagementAmadou Jaffar OuattaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Puf Citot 2022 01 0277Document72 pagesPuf Citot 2022 01 0277Stephane VinoloPas encore d'évaluation

- Balz 005 0303Document14 pagesBalz 005 0303Dominique DemartiniPas encore d'évaluation

- BE FEDE MarketingDocument40 pagesBE FEDE MarketingSarah MakePas encore d'évaluation

- Com Pol en France - Surligné - Tableaux UtilesDocument16 pagesCom Pol en France - Surligné - Tableaux UtilesLeo LacaudPas encore d'évaluation

- La Stratégie en Théories - Général DesportesDocument15 pagesLa Stratégie en Théories - Général DesportesRosmeisterPas encore d'évaluation

- Puf Citot 2022 01 0425Document51 pagesPuf Citot 2022 01 0425Stephane VinoloPas encore d'évaluation

- Rfap 183 0110Document20 pagesRfap 183 0110razandry34Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pe 234 0005Document5 pagesPe 234 0005jeanbulalu0303Pas encore d'évaluation

- Carim-Rr 2007 04Document62 pagesCarim-Rr 2007 04Mohammed ChababPas encore d'évaluation

- Guide Candidature Polytech Campus France 2020Document22 pagesGuide Candidature Polytech Campus France 2020ahmed hamza khabouzePas encore d'évaluation

- Bardout J.-C. - Malebranche Et Les Mondes ImpossiblesDocument19 pagesBardout J.-C. - Malebranche Et Les Mondes Impossiblesdescartes85Pas encore d'évaluation

- La Philosophie Africaine Et Son Historiographie: J. Obi OguejioforDocument15 pagesLa Philosophie Africaine Et Son Historiographie: J. Obi OguejioforSerge AnthonyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethn 071 0011Document13 pagesEthn 071 0011Sira B DialloPas encore d'évaluation

- Rfse 013 0009Document15 pagesRfse 013 0009malaminemalangbayoPas encore d'évaluation

- Coopération Afrique EuropeDocument14 pagesCoopération Afrique EuropenfrancisrogerPas encore d'évaluation

- Politiques Publiques Nationales Dans L'union EuropéenneDocument88 pagesPolitiques Publiques Nationales Dans L'union EuropéenneLauraPas encore d'évaluation

- Strat 129 0007Document3 pagesStrat 129 0007Karouach AbdellatifPas encore d'évaluation

- Dubernet 2018 - Analyse de Discours (Frontex)Document25 pagesDubernet 2018 - Analyse de Discours (Frontex)ghebremariamadyPas encore d'évaluation

- Appel Candidature Master Recherche en AGIFT PDFDocument6 pagesAppel Candidature Master Recherche en AGIFT PDFfdsPas encore d'évaluation

- Influence FRANCE Sur PSDocument5 pagesInfluence FRANCE Sur PSAZIZ GUEHIDAPas encore d'évaluation

- Notion de Fonction (3ème)Document3 pagesNotion de Fonction (3ème)MATHS - VIDEOSPas encore d'évaluation

- 24ème Dimanche Année CDocument2 pages24ème Dimanche Année CPatrick LessiPas encore d'évaluation

- Imprimir Imagen CompletaDocument148 pagesImprimir Imagen CompletaTati AnaPas encore d'évaluation

- VARIATEUR - DE - VITESSE - Doc ProfDocument3 pagesVARIATEUR - DE - VITESSE - Doc Profsaid100% (2)

- Guide GLPI-FusionInventory - NagiosDocument12 pagesGuide GLPI-FusionInventory - NagiosAITALI MohamedPas encore d'évaluation

- TD Tns-SticDocument3 pagesTD Tns-Sticqzsv7wpnnwPas encore d'évaluation

- FondProf Presentation TechniqueDocument21 pagesFondProf Presentation TechniqueMarc Landry FokwaPas encore d'évaluation

- Resume Du TPDocument9 pagesResume Du TPMOUGANGPas encore d'évaluation

- CHAPITRE I1 SupervisionDocument4 pagesCHAPITRE I1 Supervisionkamgabriel920Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapitre 2 - Evolutions Économiques Et Sociales Dans Les Pays Occidentaux D'une Guerre À L'autreDocument24 pagesChapitre 2 - Evolutions Économiques Et Sociales Dans Les Pays Occidentaux D'une Guerre À L'autreNazwa NubowoPas encore d'évaluation

- PMMP Formulaire D Inscription Des Entreprises 2017Document2 pagesPMMP Formulaire D Inscription Des Entreprises 2017Aalaeddine Afifi100% (2)

- Bulletin Dessai Gaine Streamline Plus 1.05l HDocument3 pagesBulletin Dessai Gaine Streamline Plus 1.05l Hhoda miliouPas encore d'évaluation

- Exploration Biologique Du FoieDocument9 pagesExploration Biologique Du FoieYounes Hadj CharefPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 Pages Retraite 11 22 v5Document4 pages4 Pages Retraite 11 22 v5Chris Walid Rizk Malaak MalaakPas encore d'évaluation

- Cours Mecanique Tekwin2Document321 pagesCours Mecanique Tekwin2Khaled Belhouchet100% (1)

- Cours - 02 - Prinicipes Et Concepts GénérauxDocument10 pagesCours - 02 - Prinicipes Et Concepts GénérauxcharefeddinetorkiPas encore d'évaluation

- IntroductionDocument12 pagesIntroductionrabeh khenPas encore d'évaluation

- Ordre Et Opérations (4ème)Document3 pagesOrdre Et Opérations (4ème)MATHS - VIDEOS75% (4)

- Cours Complet Analyse FinancièreDocument153 pagesCours Complet Analyse FinancièreMOPas encore d'évaluation

- MAROC - TELECOM - Une - Correction - Disproportionnée - en - BourseDocument8 pagesMAROC - TELECOM - Une - Correction - Disproportionnée - en - BourseYouri PlaysPas encore d'évaluation

- Vocabulaire Kabyle de L'ostéologie Et de L'orthopédieDocument330 pagesVocabulaire Kabyle de L'ostéologie Et de L'orthopédieamazighisant100% (5)

- Chapitre IV équilibre Liquide-SolideDocument8 pagesChapitre IV équilibre Liquide-SolideChamssou BoustilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapitre 434Document18 pagesChapitre 434dieudonnepooda71Pas encore d'évaluation

- Rappel Sur Le ParodonteDocument27 pagesRappel Sur Le Parodontemisha melissaPas encore d'évaluation

- Recyclage Dechets Plastiques Converti ConvertiDocument15 pagesRecyclage Dechets Plastiques Converti ConvertiYoo BahPas encore d'évaluation

- PHARMACIE VETERINAIRE Cours de Pharmacie Galénique 3eme Année Pharmacie DR CHIKH PDFDocument62 pagesPHARMACIE VETERINAIRE Cours de Pharmacie Galénique 3eme Année Pharmacie DR CHIKH PDFInes SahraouiPas encore d'évaluation

- TP #1 CristallographieDocument14 pagesTP #1 CristallographieMohamed CHIBANPas encore d'évaluation

- 10-DS Chaîne de MontageDocument3 pages10-DS Chaîne de MontagesaulnierPas encore d'évaluation