Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Jie 033 0105

Transféré par

Christian CastilloTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Jie 033 0105

Transféré par

Christian CastilloDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Business Model Innovation in a Network Company

Amina Hamani, Fanny Simon

Dans Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 (n° 33) , pages 105 à 134

Éditions De Boeck Supérieur

DOI 10.3917/jie.033.0105

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

Article disponible en ligne à l’adresse

https://www.cairn.info/revue-journal-of-innovation-economics-2020-3-page-105.htm

Découvrir le sommaire de ce numéro, suivre la revue par email, s’abonner...

Flashez ce QR Code pour accéder à la page de ce numéro sur Cairn.info.

Distribution électronique Cairn.info pour De Boeck Supérieur.

La reproduction ou représentation de cet article, notamment par photocopie, n'est autorisée que dans les limites des conditions générales d'utilisation du site ou, le

cas échéant, des conditions générales de la licence souscrite par votre établissement. Toute autre reproduction ou représentation, en tout ou partie, sous quelque

forme et de quelque manière que ce soit, est interdite sauf accord préalable et écrit de l'éditeur, en dehors des cas prévus par la législation en vigueur en France. Il est

précisé que son stockage dans une base de données est également interdit.

VARIA

Business Model Innovation

in a Network Company

Amina HAMANI

Universty of Normandie Caen

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

Nimec (France)

Amina.hamani@unicaen.fr

Fanny SIMON

University of Normandie Rouen

Nimec (France)

fanny.simon-lee@univ-rouen.fr

ABSTRACT

Currently, many organizations deploy business model innovation (BMI) to

respond to changes in their environments. Most studies have focused on

understanding BMI only at the organization level and have not explained

how it can emerge from a bottom-up process and be diffused at the network

level. Consequently, challenges related to the co-existence of BMs in a net-

work company have not been explained, potentially leading to the failure

of the new BMI. The aim of this paper is to fill this void through a single-

case study of CH Robinson Europe, a transportation and logistics services

company. We study a particular BMI that disrupts existing behaviours and

resource flows as it was deployed at the organizational and network levels.

This case study demonstrates the coordination and collaboration challenges

stemming from the complex relationships between actors, due to their inter-

dependence and the complementarity of business models at different levels.

Therefore, our findings extend our understanding of the emergence and dif-

fusion of a BMI in network organizations and of the role played by inter-

organizational relationships in value capture from BMI.

KEYWORDS: Inter-organizational Relationships, Business Model, Network, Value

Creation.

JEL CODES: O3

n° 33 – Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 105

DOI: 10.3917/jie.033.0105

Amina Hamani, Fanny Simon

In the current rapidly changing environment, companies need to reconsider

their value creation process and delivery to customers (Chesbrough, 2007;

Teece, 2010). Consequently, they are increasingly using inter-organizational

relationships to search for new logics of value creation (Börjeson, 2015;

Latusek, Vlaar, 2018; Ruiz-Ortega et al., 2017). Such new logics, along with

the original mechanisms of value capture, are a source of business model

innovations (BMI). According to Abdelkafi et al. (2013) BMI deals with

changes in a value dimension of the company’s business model. It enables

sustainable competitive advantage and facilitates responsiveness to change in

the environment (Demil et al., 2018; Schneider, Spieth, 2013).

As early as 2002, Zott and Amit (2002) highlighted that BMI differs from

product or service innovations and requires focused studies. Although a well-

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

established stream of research has examined BMI, existing analyses often

focus on a single entity, whereas BMI involves transformations of inter-orga-

nizational relationships. Indeed, the definition of the business model (BM) as

a system of interdependent activities transcending the focal firm and span-

ning its boundaries emphasizes interdependencies beyond a firm’s boundaries

and the impact of interlinkages between organizations (Zott, Amit, 2010).

Consequently, we aim to obtain a better understanding of BMI and of how

the new and the existing BM co-exist in complex networks of organizations.

More particularly, we focus on the emergence of BMI through inter-organi-

zational relationships and the alignment of that BMI within the focal com-

pany’s network relationships (Foss, Saebi, 2017; Kringelum, Gjerding, 2018;

Rydehell, 2019; Spieth et al., 2019a).

Whereas most studies of BMI consider initiatives that emerge from top

management and are deployed throughout the organization, we concentrate

on a BMI that emerged from specific local conditions and was developed via

a bottom-up process (Mutka, Aaltonen, 2013). The challenge in this case

was to organize and coordinate networks for the innovation with an initial

BM and simultaneously to sustain existing relationships. Few research studies

have explored how such BMIs emerge and how they co-exist with an existing

BM at the network level (Foss, Saebi, 2017).

This paper brings new insight to the literature on BM dynamics by high-

lighting conflicts in resource allocation between the two business models as

well as different mechanisms of value capture, which may later create tension

if the BMIs interfere with the firm’s BM. Furthermore, we use the literature

on inter-organizational relationships in the context of innovative projects to

understand the challenges raised by the alignment of a BMI with the firm’s

BM and with partner organizations’ BMs. In fact, as a firm’s BM interacts

106 Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 – n° 33

Business Model Innovation in a Network Company

with other companies’ BMs, a BMI in the focal company may disrupt core

elements of other organizations’ revenue models.

Our research focuses on one of the leading providers of multimodal

transportation services and third-party logistics in the US. This organiza-

tion mostly offers freight transportation and brokerage services. Its worldwide

presence is characterized by a network of more than 280 entities. We study

a specific BMI, which involves suppliers and different entities in a network

of organizations and customers. This BMI, which at first appears to be suc-

cessful, can be characterized as an inter-organizational project because it is

temporary and several actors with different backgrounds and localizations

are involved. However, as the BMI was deployed into the network, major

organizational changes occurred, as well as substantial transformations of

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

the relationships within the network and with suppliers. Consequently, a new

organizational form was designed to enable the deployment of organization-

wide capabilities, and the existing BM at the firm level had to be amended.

We conducted a qualitative and case study analysis based on the process and

on content approaches. We extracted and coded data into the network to

characterize both the different dimensions of the BM and the changes in

relationships among the entities in the network.

This paper shows that, as a new BMI is deployed, actors specifically focus

on mechanisms through which to create value inside the network, whereas

one of the main challenges is to capture value from the BMI without destroy-

ing existing BMs at the firm level. The integration of different levels of analy-

sis for the BM as well as the focus on a dynamic approach facilitates an under-

standing of the tensions that occur as new BMIs are deployed in a network

company.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we build a theoretical framework

for the BM concept and its deployment in a network organization, followed

by a discussion of how BMs can co-exist at different levels in a network orga-

nization. Second, we present our research methodology design and describe

our case study. Finally, we discuss the results compared to those of previous

studies.

Theoretical Framework

Defining a BM at Different Levels of Analysis

Over the last twenty years, we have witnessed a proliferation of academic

research on BMs (Demil et al., 2018; Foss, Saebi, 2017; Massa et al., 2017;

n° 33 – Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 107

Amina Hamani, Fanny Simon

Rydehell, 2019). One of the most popular definitions, which focuses on the

relationships that a focal firm maintains with others to perform its activities,

conceptualizes a BM “as a new unit of analysis, offering a systemic perspective

on how to ‘do business,’ encompassing boundary-spanning activities (performed

by a focal firm or others), and focusing on value creation as well as value capture”

(Zott et al., 2011, p. 1038). Consequently, relationships with customers, sup-

pliers, service providers and other stakeholders influence a firm’s capacity to

create and capture value (Casadesus-Masanell, Ricart, 2010). Indeed, BMs

do not operate in isolation; they interact with various actors (Chesbrough,

Schwartz, 2007). In that respect, the main contributions of the BM as dis-

cussed in the strategy literature are threefold. First, BMs show that value

creation does not come solely from producers but may also be generated by

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

customers or other involved actors. Then, a BM derives competitive advan-

tage from both the demand and the supply sides, and that advantage can

be resource- or activity-based (Massa et al., 2017). Finally, it comprises the

firm and network level, and value creation and capture are conceived beyond

the company’s boundaries (Clauss, 2017). The BM then represents a relevant

framework to analyse value creation both within the company and externally

at the inter-organizational level (Spieth et al., 2019a).

To sustain their competitive advantage, companies need to renew their

BMs, and it is thus important to regard the BM from a dynamic perspec-

tive (Wirtz et al., 2016). Those changes in BM can lead to two different

types of BMIs: the re-configuration of the initial BM or the creation of a

new BM (Massa, Tucci, 2014; Laasch, 2019). We focus on the creation of

a new BM through adjustments involving voluntary and emerging changes

in and between BM components (Demil et al., 2018). In established com-

panies, those transformations have to be managed simultaneously with the

reinforcement of the traditional BM (Khanagha et al., 2014).

Despite the interest that scholars accord to BMI, they agree that much

remains to be explored (Demil et al., 2018; Foss, Saebi, 2017; Gassmann et al.,

2016; Massa et al., 2017). In particular, BMI allows consideration of both

changes within the company and the dynamics in its value network (Spieth

et al., 2019a). That network includes the focal firm and its partner organi-

zations, such as customers, suppliers and various stakeholders, and it influ-

ences both joint value creation and distribution (Amit, Zott, 2015; Wirtz

et al., 2016). However, we still have little understanding of the implications of

BMI on the value network (Kringelum, Gjerding, 2018; Rydehell, 2019). This

topic is of particular interest for network companies, which rely on their rela-

tionships with partners to innovate (Spieth et al., 2019a; Alcalde, Guerrero,

2016). Furthermore, in such an organizational form, different entities can

108 Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 – n° 33

Business Model Innovation in a Network Company

create value and benefit from the arrangement. Consequently, “the value cre-

ated at one level of analysis can be captured at another” (Solaimani et al., 2018,

p. 81). The challenge for such a company is to involve partners in the BMI

process while simultaneously deploying a BMI that can maintain value cre-

ation for the different actors involved in its value network, not only for its

clients, in order to remain competitive (Zollo et al., 2018).

Researchers have already highlighted the challenges related to BMI

in network organizations. First, BMI can compete with the initial BM for

resources or lead to new processes that may conflict with current practices

in the organization. Hence, BMI can be used to explore new paths and may

be disruptive to the existing network. Demil et al. (2018) demonstrate that

the focal company needs to negotiate with stakeholders to convince them

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

to interact in the value creation and capture processes under the conditions

expected by the focal organization. The failure of complementors, suppliers

or distributors to rally around the BMI often leads its implementation to fail.

Second, BMI can jeopardize the value creation mechanisms of the exist-

ing BMs. Thus, the co-existence of two systems of value generation may

increase costs more rapidly than turnover, which would decrease the firm’s

profitability (Moingeon, Lehmann-Ortega, 2010); cannibalization can also

occur between the BMs (Khanagha et al., 2014); and the value of the exist-

ing distribution network can be undermined (Markides, Charitou, 2004).

Chesbrough (2010) also notes that organizational processes need to change,

and resources must be allocated differently.

To overcome these different challenges, researchers have prescribed dif-

ferent organizational arrangements. The first stream of research considers

that companies should experiment within temporary structures. The new

BM should be developed in separate structures and then reintegrated into

existing business units (Markides, 2013). A second perspective considers that

companies should find a balance between an exploitation and an explora-

tion logic in their value network. Thus, BMI can first be orchestrated by

leveraging incremental changes within the focal company, and then new

opportunities are uncovered at the network level and new mechanisms of

value creation are explored with external partners. Those minor transfor-

mations could lead to major reconfigurations of the value network and the

exploration of co-created new offerings (Kringelum, Gjerding, 2018). We fol-

low this line of argument and focus on the process of BMI. That process is

characterized by a feedback loop between value creation and capture (Rodet-

Kroichvili et al., 2014). The RCOV model is particularly appropriate for cap-

turing those gradual transformations of value creation and capture within

n° 33 – Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 109

Amina Hamani, Fanny Simon

the value network, as it allows a dynamic perspective (Wirtz et al., 2016). We

describe this model in the next section.

The RCOV Model

Various generic BMs have been proposed in the literature (Moingeon,

Lehmann-Ortega, 2010; Osterwalder, Pigneur, 2010); we focus on the RCOV

model, as described by Warnier et al. (2016), because it explicates a multidi-

mensional view of the firm and allows a dynamic perspective (Gassmann

et al., 2016; Warnier et al., 2018).

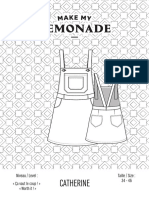

Figure 1 – The RCOV model

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

Adapted from Warnier et al. (2016)

As shown in Figure 1, the model is characterized by three compo-

nents: resources and competences, value proposition and organization. The

resources and competences component encompasses assets as well as indi-

vidual and collective capabilities, which are valuable and may be unique.

Selecting the appropriate capabilities and assets to mobilize defines the offer-

ings for customers. The perceived value that customers attribute to those

offerings and the prices that they are willing to pay for them define the value

proposition and the revenue structure. Then, the company must organize

its internal value chain and determine which activities to outsource. Such

choices impact the cost structure and the value network. The value chain

and network define the organizational component. The difference between

110 Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 – n° 33

Business Model Innovation in a Network Company

receipt and payment flows defines the company’s margin and determines its

profitability. Details of the four components are described in Table 1.

Table 1 – BM components according to the RCOV approach

-The physical, financial or human

resources that different actors control

or draw from the external environment

Resources -Those resources can be bought,

rented, produced internally or

Resources acquired from partnership, and they

and enable revenue generation

competences -The capability and know-how

developed by managers individually

or collectively to improve, combine

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

Competences

or change the way resources are

used and that lead to different value

propositions

Every entity that generates revenues

Clients can be final consumers,

Clients

suppliers, competitors or partners

Value offering complementary products

proposition Offer Services and products of the company

Includes the “place” for each phase

Access of the buying process, including

conditions as well as price

Internal Organization: The activities of the company that are

Value chain carried out internally

Organization The relationships that a company has

External Organization:

with different external partners to

Value network

deliver value

These three components (resources/competences/organization/value

proposition) represent organizational choices. A BMI can then be associated

with changes in those components. Thus, Spieth et al. (2019a) decompose

BMI in three dimensions:

–– VOI (value offering innovation), which relates to innovations that pro-

vide additional value for customers;

–– VAI (value architecture innovation), which describes the restructuring

of company internal resources and partner networks;

–– RMI (revenue model innovation), which relates to changes in the net-

work value capture mechanisms.

These different innovations in the BM components not only transform

the firm’s BM but also the BMs of its partners (Casadesus-Masanell, Ricart,

2010). Consequently, as proposed by Spieth et al. (2019a), we study BMI from

a network perspective. As that perspective is quite new in the literature, we

n° 33 – Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 111

Amina Hamani, Fanny Simon

bring complementary insights by leveraging the literature on inter-organi-

zational relationships in innovative projects. In fact, this research stream

has demonstrated that companies can regenerate their portfolio of offerings

and have dynamic BMs through ideas emerging from inter-organizational

partnerships (Leboulanger, Perdrieu-Maudière, 2012). For example, suppli-

ers, in particular, can be sources of new ideas (Jouini, Charue-Duboc, 2018).

However, new value creation offerings from external partners may disrupt

value capture mechanisms and reshape the organization of the whole net-

work. Consequently, in the next section, we highlight the different dimen-

sions of inter-organizational relationships that may influence the emergence

of a new BM or the co-existence of BMs.

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

Characteristics of Inter-Organizational

Relationships and BM Co-Existence

We focus our analysis on the networking form of company (a ‘network

company’, for short), which has seen renewed interest in recent decades

(Clegg et al., 2016; Ricciardi et al., 2018). Numerous companies deploy vari-

ous forms of networks to enter international markets or externalize their

activities. These networks provide resources to the company embedded in

them, allowing them to generate profit (Barney, 2018; Ruiz-Ortega et al.,

2017). Previous scholars have pointed out that networking also enhances

innovation, flexibility and the development and diffusion of new knowledge

(Solaimani et al., 2018). Network companies are characterized by particular

patterns and relationships among different companies that conduct common

activities. As BMIs are deployed in network organizations, companies tend

to realign their objectives to create joint value (Demil et al., 2018). Thus,

network companies are characterized by a high degree of integration between

multiple types of socially important relations across formal boundaries, which

determine the success of BMI.

In network companies, value creation mostly comes from the network

of internal and external relationships. Value creation refers to the choice of

activities (content), the interlinkage and sequence of those activities (struc-

ture) and role repartition for those activities (governance) (Zott, Amit, 2010;

Spieth et al., 2019b). In addition, the nature and flow of value transactions

and exchanges should be considered (Weerawardena et al., 2019). Similarly,

networks can be characterized in terms of content (type of resource flows,

which are related to activity choices), structure (densely or loosely connected

ties) and governance (coordination within the network). Consequently, we

define how inter-organizational relationships can be impacted by BMI.

112 Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 – n° 33

Business Model Innovation in a Network Company

Bankvall et al. (2017) differentiate between firm-centric and network-

embedded BMs. As far as inter-organizational relationships are concerned,

structural embeddedness refers to densely connected groups and companies

that maintain ongoing and close relationships with partners (Uzzi, 1996).

The BMs of firms that are densely embedded into networks of relationships

cannot change independently (Bankvall et al., 2017). The transformation of

a single company’s BM impacts the BMs of other firms. Furthermore, compa-

nies that are refining their BM may have to extend their set of relationships.

Network extension can later lead to more radical BMI (Kringelum, Gjerding,

2018). Consequently, BMI transforms the set of inter-organizational relation-

ships in terms of its structure.

Different types of content also flow in relationships such as information,

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

equipment, materials and support. Traditionally, research on BMs emphasizes

exchanges of tangible resources as well as financial and information flows

in networks of relationships. Thus, companies use their inter-organizational

network to convert different types of resources into sources of value (Allee,

2008). However, less attention has been paid to social resources such as sup-

port, legitimacy or trust, which are also important for innovation (Newell,

Swan, 2000). Thus, recent works by Bourcet et al. (2019) demonstrate that

trust is needed in specific conditions to reinforce value creation, but it may

be impeded by information asymmetries in the network (Bourcet et al.,

2019). As companies conjointly develop BMI, social mechanisms within

the network will be strengthened. Partners then work iteratively, and cer-

tain relationships, which at first were temporary, are reiterated and may

become permanent. Thus, staff from different companies will get to know

each other better and become more likely to trust each other. Consequently,

BMI would change resource flow with the set of inter-organizational relation-

ships. Finally, studies on inter-organizational relationships have highlighted

the role of network coordination on value creation and capture. In particular,

Dhanaraj and Parkhe (2006), highlight the role of hub firms in orchestrating

the network and allowing value extraction, notably by managing innova-

tion appropriability. However, as BMIs are deployed in the network, it may

become difficult to align a constellation of companies with diverging interest

(Berglund, Sandström, 2013). Thus, the focal firm alone may not be able to

manage changes in the network, and BMI deployment may be blocked by

members of the value network.

To synthesize, companies that develop BMI in complex networks face

several structural challenges. First, they need to support the BMI as well as

to maintain the existing BM. This could be particularly challenging, as the

structure of the network and the type of resource flow in the set of ties are

n° 33 – Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 113

Amina Hamani, Fanny Simon

transformed with the BMI. As a consequence, those structural conditions

that are favourable for BMI may be detrimental for the continuity of the BM.

Then, the focal firm may not be able to orchestrate those changes in the net-

work, which may trigger resistance from members of the value chain. These

tensions, which have not been studied in the literature, led us to unpack the

dynamics of BMI development in network organizations.

In this research, we focus on a case study of a network company that

established a new BMI. The BMI challenged the firm and the network’s BM.

Consequently, the company went through several trials to attempt to align

its different BMs. The following section describes the case studied and the

methods.

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

Methods

We conducted a qualitative single-case study of a transportation company

that is organized as a network of independent companies. The individual

case study approach facilitates gaining insight from a specific case with a

unique context and is particularly appropriate for studying transformations

of BMs and value creation (Moyon, Lecocq, 2014; Achtenhagen et al., 2013).

This case is particularly apt for studying changes in BMs and inter-organi-

zational relationships, as the network of organizations involves both a dense

set of internal agencies and looser ties with external providers. We hereafter

refer to the entity in which the BMI emerges as the “Agency”. We began by

presenting the case.

Case Description

CH Robinson Worldwide is the leading provider of multimodal transpor-

tation services and third-party logistics. This company was set up in 1905,

and its headquarters are in Minnesota, USA. It provides clients with logis-

tics solutions as well as transportation services and technological solutions

worldwide. The company draws its competitive advantage from its expertise

in logistics processes and from specific technological tools as well as from its

worldwide network of agencies.

CH Robinson Europe BV comprises 43 agencies in 19 European coun-

tries. Its agencies are logistics service providers and act as brokers. The

agency we are studying is specialized in road transport for all types of goods.

The Agency operates in a specific geographical zone that has been allocated

to it. All clients domiciled in that zone are referred to the Agency, and no

other agency can interfere in the zone. The Agency does not own trucks

to transport its customers’ goods, thereby eliminating the costs of acquiring

and managing trucks. It charters carriers with different nationalities in all

114 Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 – n° 33

Business Model Innovation in a Network Company

European zones, from the point of loading to the point of delivery, which

enables the Agency to offer lower prices than its competitors. Therefore, we

can represent the component of the initial BM as follows.

In 2012, the Agency started to use the same truck and driver to pro-

pose round-trip contracts and paid the transporter based on the kilometres

travelled instead of per discrete trip. Then, the Agency formed partnerships

with certain transport providers. These carriers would commit their trucks

to the Agency for periods of time. Carriers were then paid, based on kilome-

tres travelled, with a minimum monthly fee, such that the Agency had total

control of the truck. This arrangement between the Agency and their trans-

porter represents a BMI, as it represents a new value proposition for clients

and changes in the “organization” dimension of the BM. This BMI was sub-

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

sequently extended across the Agency’s network and led to transformations

in both the firm and its network’s BM. We detail our methods for analysing

changes in the BM and inter-organizational relationships; then, we present

our results. Table 2 presents the initial BM of the company.

Table 2 – The initial BM components of CH Robinson

according to the RCOV approach

Components Description

Financial resources

Physical, financial and

Head office

human resources that

28 employees

CH Robinson Agency

Navisphere platform,

holds, develops

provided by the

internally or obtains

Resources headquarters, CH

from the external

Robinson Worldwide

environment, through

Trucks provided by

buying, renting

CH Robinson network

and acquiring from

Trucks provided by

partnership

carriers

Bargaining skills and

Resources knowledge of foreign

and languages

competences Skills developed

collectively with CH

The capability and

Robinson network:

know-how developed

Knowledge about

by CH Robinson

transportation market

Competences Agency managers

price

individually or

Expertise on

collectively with the

European zones

CH Robinson network

and on coordination

between these zones

Carriers’ profiles

Knowledge of regional

specificities

n° 33 – Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 115

Amina Hamani, Fanny Simon

Components Description

Direct customers

Other agencies

Every entity that from CH Robinson

generates revenues European network

Clients

for the CH Robinson which has

Value Agency merchandise to

proposition transport on the

assigned zone

Services provided Road transport across

Offer by the CH Robinson Europe for all types of

Agency merchandise

Prospecting for clients

The activities of the

from its assigned zone

CH Robinson Agency

Value chain Finding carriers in

that are carried out

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

European zone at the

internally

best value for money

Organization Punctual relationships

The relationships that

with carriers on the

CH Robinson Agency

spot market

has with different

Value network Cooperation with

external partners to

CH Robinson Europe

create and deliver

network to serve their

value

respective clients

Longitudinal Case Study

We carried out a longitudinal analysis to study changes in the BM and

inter-organizational relationships based on the earlier prescribed methods

(Moyon, Lecocq, 2014). We integrated both process and content approaches.

Our data analysis jointly used secondary and primary data representing a

seven-year period (from 2010 to 2017); these data were cross-checked with

different sources to enhance the study’s validity. The primary data were gath-

ered through semi-structured interviews. Each interview lasted from 30 min-

utes to 1 hour. These data were collected at two different periods to follow

BM evolution. We also went to the site and observed working practices. In

terms of secondary data, we had access to internal reports, the organizational

chart and general information about the company’s organization. Table 3

synthesizes the different sources of data.

116 Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 – n° 33

Business Model Innovation in a Network Company

Table 3 – Information sources

Primary data Secondary data

2016: 9 interviews with managers,

customers, quality managers and

account representatives as well as CH Robinson Worldwide annual

participants’ observations and a report, 2010 and 2016

meeting with the General Manager, Internship reports of 2015 and 2017

Customer Manager and CH Robinson Research paper of 2016

Quality Manager Organizational chart of 2010 and 2012

2017: 6 interviews with managers, Press articles from 2007 to 2017

dedicated truck account managers

and account representatives

First, we wrote a narrative, which we had validated by an expert, to study

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

the evolutions experienced by the BMs and their contexts. That narration

allowed us to identify the key events that shaped the BMI.

Then, we used a content approach to understand how the BM and the

inter-organizational relationships evolved throughout the three phases, sim-

ilar to the method used by Ziaee Bigdeli et al. (2016). We first performed

thematic coding of the BM at different levels according to the three main

components used in the RCOV framework (resources and competences,

organization and value proposition). Then, we coded inter-organizational

relationships according to the different features described in the literature

review.

Next, we described the components of the BM concept as they existed at

different periods of time, and we compared them to identify innovations in

the BM (Casadesus-Masanell, Ricart, 2010). We also determined the attri-

butes of the inter-organizational relationships, which allowed us to under-

stand the interrelationships between BMI and the inter-organizational rela-

tionships.

Results

We organize the results section according to the three phases that char-

acterized the BMI. The first phase began as a team in the Agency was setting

up the new BMI. The second phase ended as difficulties arose and the new

organization was scrutinized; the last phase is characterized by the decision

that the new BMI should remain at the Agency level. Figure 1 represents the

initial BM. It particularly highlights the competition within the external

network and the cooperation inside the internal network, which ensure a

high profit for the company.

n° 33 – Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 117

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

Figure 2 – The initial BM

118

Amina Hamani, Fanny Simon

Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 – n° 33

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

Business Model Innovation in a Network Company

Description of the BMI and the

Changes in the Firm’s BM

The BMI emerged from changes in the context: specifically, the opening

of the European Union triggered new opportunities for change in the freight

sector. Hence, the enlargement of the European Union towards the countries

of Eastern Europe between 2004 and 2007 opened the market to Polish and

Romanian carriers, which became the main actors in the European freight

transport market. These carriers seek to work with transportation companies

that provide them with orders on a regular basis. In this case, the Agency

used to work with Eastern European carriers. The embeddedness of relation-

ships with those carriers opened the way for a BMI. Even though this BMI

was highly related to this particular context, it was subsequently adopted by

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

the US headquarters and was developed worldwide.

The BMI involved both a new value proposition for the client and a new

organization. The Agency guaranteed carriers a certain number of kilome-

tres per month. In exchange, carriers provisioned their trucks to the Agency

for periods ranging from 2 to 4 months. Hence, the Agency then became

responsible for loading, tracking deliveries in time and place, and sending

trucks to other loading locations, whereas traditionally, it had only been in

charge of finding a transporter at the best price to do these tasks. Henceforth,

it assumed total control of the trucks and came to handle them as if it owned

them.

Value Proposition

The introduction of dedicated trucks allowed the Agency to make a new

proposition to its customers because it now controlled the truck’s itinerary.

Previously, the Agency had chartered trucks on the spot. However, for vari-

ous reasons, transporters preferred certain destinations to others. In addi-

tion, in certain periods of the year there was greater demand than available

means of transport; transporters became less available, and transport prices

soared. Furthermore, it became difficult to contractually set the conditions

of the trucks prior to loading, which could adversely affect the quality of

service and customer satisfaction. Finally, for certain trips, customers had

to pay a very high price because the Agency could not find any load for the

return trip, and the customers had to pay for the empty truck to return to its

initial location. Consequently, the Agency could not guarantee its offering

to its regular customers. The new value proposition provided a certain level

of quality to customers by monitoring the trucks, which could be sent to the

loading point, as described by the following verbatim transcript outlining

the new value proposition: “Customers want to pay less, so we look for the

n° 33 – Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 119

Amina Hamani, Fanny Simon

cheapest… and when it’s cheaper, the quality is not always excellent, and it’s really

difficult to manage everything, so now with the trucks that circulate, it is ours,

so we can guarantee a certain quality, and it can stabilize our prices.” (Account

Representative)

This BMI also prices to be anticipated and assurances provided for a given

offering for certain destinations. Finally, it enables lower prices by loading

trucks for round-trip travel, and it aims to address customers’ needs with

greater flexibility and customization, as described below: “For example, I was

talking about loads to Bretagne that are very difficult to get out; the trucks belong

to us, so we can move it to Bretagne because we already have internal knowledge

to provide the re-out, so we can meet the specific and complicated needs of cus-

tomers.” (Dedicated Truck Account Manager).

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

Resources and Competences

The Agency’s BM relies on one main resource to manage all its activities:

a technological platform called the “Navisphere”. This platform was devel-

oped by CH Robinson Worldwide and connects all its agencies throughout

the world. It comprises a database where CH Robinson agencies share their

information and knowledge of their customers and carriers to optimize pro-

cess and transportation flows. In addition, the Agency mobilizes two types of

logistical and transportation skills: skills that are developed individually by

the Agency’s staff (such as bargaining skills and expertise in the geographical

zone) and skills developed collectively within the CH Robinson Europe net-

work (such as coordination among zones). These skills principally concern

transportation in terms of price, transporter profiles, and region specifici-

ties, as described in the following verbatim transcript: “If we take the case of

UK imports to go to France, the Agency is not [a] specialist, but the agency of

Manchester and London know very well how to do that. So, if we want to have a

chance to better position our offer in terms of price, it is better to ask the agency of

Manchester or London.” (Client Manager)

The resources and competences component has also undergone several

changes. The main transformation is that the Agency has trucks available

(thus, a new tangible asset). The team in charge of the BMI also acquired new

skills insofar as its members now have deep knowledge of the driver and truck

with which they are working. Moreover, they have to carry out new duties,

such as finding loads for a truck and optimizing the truck’s itinerary, and

develop new skills, such as knowledge of Europe’s zones, because the “dedi-

cated trucks” cover all Europe. Thus, they have developed new competences.

120 Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 – n° 33

Business Model Innovation in a Network Company

Internal Organization

The value chain of the existing BM is organized around two services: cus-

tomer service, whose primary mission is to find new loads, and the mission of

the carrier service, which is to find transporters for these loads. Responsibility

for the transport of goods may be assigned directly to the Agency’s carrier

service or may be entrusted to a carrier service belonging to another agency

of CH Robinson Europe network that proposes transporters. This structure

characterizes all CH Robinson Europe agencies: “Each agency works in the

same way [with regard to its] customer and carrier service. Customer service cre-

ates an order, for example from Paris to Madrid, [and] there are two choices that

are offered to Paris customer service; either they choose the carrier service of [the]

Paris Agency, which assigns the truck, or it can choose another agency of the

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

group that assigns this truck.” (General Manager)

The BMI completely changes this organization. The Agency has added

a new service in its organizational chart. This service supports a new pro-

cess by which to circulate and guide dedicated trucks throughout Europe. Its

objective is no longer to find trucks for customers but instead to search for

loading opportunities (hence customers) for dedicated trucks from potential

customers in its zones or from the CH Robinson Europe network in other

zones: “Most of the people who work here are looking for trucks for loading, and

dedicated trucks are looking for loading for their trucks…” (General Manager)

External Organization

In terms of the value network, the relationships with transporters were

disrupted. The task allocation between the Agency and its transporters was

altered, and the Agency now provides more value for the transporters. Thus,

these carriers have entrusted their trucks to the Agency for a short period.

The Agency then covers round trips with the same truck and the same driver

and provides a minimum fee to the carrier for a given period. Hence, the

relationship between the Agency and those transporters has evolved from an

on-the-spot market transaction to long-term cooperation, as described in this

verbatim transcript: “Those transporters are interested in transport companies

that provide them regularly with loads; for them, it is another way to run their

trucks, with very little investment, because we make everything for them, and we

choose the loading from point A to a point B, and from point B to a point C, and

so on.” (General Manager)

Transformation of Inter-organizational Relationships

The BMI was triggered both by new demands from customers and new

opportunities from carriers. Thus, the mutual trust between certain carriers

n° 33 – Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 121

Amina Hamani, Fanny Simon

and the Agency allowed mobilization of a new resource: dedicated trucks

without formalizing a contract, as described in the following verbatim tran-

script: “We do not make a contract; we are really flexible for the moment. There

are things signed in some cases, but it is never signed for duration.” (General

Manager)

The embeddedness of the Agency with those transporters allows progres-

sive validation of the BMI. This new BM also contributes to a strengthening

of relationships with specific carriers, as they regularly work with the Agency.

Thus, in terms of inter-organizational relationships, the BMI implies multi-

plex relationships with external partners who share both tangible resources

(trucks) and intangible resources (knowledge). The intensity of exchange is

high, as organizations frequently work together. The network structure is

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

embedded because ties must be set up among partners to ensure maximum

loading for each truck. This structure is based on informal governance mech-

anisms, such as trust and reciprocity.

The BMI has also impacted relationships among agencies. Hence, tradi-

tionally, the revenue allocation among CH Robinson Europe agencies has

led to uncivil competition between carrier services. At present, each agency

is in charge of a specific zone, and it can only serve customers from within

this zone. However, the carrier service of each agency can propose transport-

ers from all Europe not only to its customer service but also to the customer

services of other agencies. The revenue component of the firms’ BM is based

on the margin that its customer services and carrier services can earn, as

described in the following verbatim transcript: “If we make 1 euro of margin,

50% goes to the customer service because it had prospected the customer, and

50% goes to the carrier side, which had dealt with the transportation, so if I take a

load from another agency, 50% goes to the carrier service of my agency, and 50%

remains for the customer service of this other agency. It is then interesting for us to

get the loads from other agencies.” (Account Representative).

They compete to obtain loadings from customer service entities, while at

the same time, they aim to access resources at the best price (by competing in

bids for transporters). Our results therefore show that the firm existing’s BM

aims at capitalizing on its CH Robinson Europe network agencies to obtain

synergistic effects in terms of resources and competences. However, relation-

ships between the Agency and its CH Robinson Europe network are char-

acterized by a low level of embeddedness because they only work together

when they need to or when they can maximize their economic profitability,

but they do not maintain strong social relationships. The BMI involves a

transformation of those relationships. Because each CH Robinson agency

has an assigned geographical zone and cannot surpass it, sending trucks to

122 Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 – n° 33

Business Model Innovation in a Network Company

other loading zones (knowing that the trucks will not circulate and can-

not return empty to the Agency) therefore requires accepting loadings from

the other CH Robinson Europe agencies responsible for those zones. Its per-

formance depends on cooperation and complementarity between the differ-

ent CH Robinson Europe agencies. Otherwise, the dedicated truck returns

empty to Paris, and the Paris agency pays the carriers for these kilometres

despite the truck’s being empty: “It’s about having the trucks available from the

other agencies, loadings available from the other agencies, because it really works

only if we have the loading of the other agencies because it is the network finally…”

(General Manager)

Because the BMI was successful at the Agency level, it was subsequently

integrated by the CH Robinson Europe network, as each agency of this net-

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

work operated in the same way and was looking for solutions. That led not

only to an evolution in the firm’s BM but also in the external network’s BM.

We discuss in the following section the path of this evolution in detail.

The Experimentation Phase at the

Firm and Network Level

BMI was progressively deployed in the other agencies as described below:

“It began when I started working at CH Robinson: at the beginning, we made

back and forth trips with the trucks; then, we decided to really handle trucks and

roll them all over Europe…. So, using our network, we managed the trucks…”

(Dedicated Truck Account Manager)

While the new value proposition was simply extended to all European

customers of CH Robinson, the organization and the resources and compe-

tences components of the network’s BM were amended, as described below.

Resources and Competences

Once all CH Robinson Europe agencies had integrated the BMI, certain

coordination mechanisms were deployed: the “dedicated truck” became a

focal priority in the Navisphere platform, with each agency being responsible

for exchanging information regularly and sharing its loadings with dedicated

trucks within its zone. Furthermore, CH Robinson agencies in Europe were

no longer competing for trucks and instead could focus on commercial activi-

ties: “I have four dedicated trucks, and I’m going to circulate them in Europe…We

often found loads for the dedicated truck because we have the platform and have

access to all CH Robinson loads throughout Europe, and we have the priority if

we have a dedicated truck…” (Account Representative)

n° 33 – Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 123

Amina Hamani, Fanny Simon

The truck fleet also expanded to include different European carri-

ers, which relates to the acquisition of new tangible resources. Thereafter,

employees developed a better understanding of the conditions related to spe-

cific trips in Europe to determine where dedicated trucks should be allocated.

They also developed their coordination skills with specific drivers. These

skills mainly concern transportation with regard to price, transporter pro-

files, the specificities of certain regions, etc.

“With what we do with the truck that moves, because moving every-

where in Europe…. So, you can imagine that when the truck arrives

in Barcelona, I cannot use something that is at my Agency to make

it move, so I have to go through the Barcelona Agency.” (Dedicated

Truck Account Manager)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

Internal Organization

In terms of the value chain, the Agency has added a new service in its

organizational chart. This service facilitates the circulation and guidance of

dedicated trucks throughout Europe. It finds loads either from potential cus-

tomers in its zones or from the CH Robinson Europe network in other zones,

as described in the following verbatim transcript: “[Traditionally,] most of the

people who work here are looking for trucks for loading, whereas the department

in charge of the dedicated trucks are looking for loading for their trucks, but there

is place for both organizations.” (General Manager)

This verbatim transcript describes the co-existence of the two BMs set up

in different organizations. This co-existence also impacts the cost structure,

as the network now needs to cover higher fixed costs (fees need to be paid

to carriers regardless of the contracts generated by customers), whereas previ-

ously, it mostly sought to manage marginal costs.

External Organization

In terms of the value network, the BMI leads to closer relationships with

carriers’ services within the CH Robinson network, who no longer compete

for trucks. Instead, they focus on commercial activities and negotiate to

obtain the loads of other agencies. This is described in the following quote:

“…You just have to respect, because when you come out of your zone and you

take loads of other agencies, this is where a little negotiation [occurs] for the price.

So, you have to negotiate with the other agencies to have their loads, but in my

opinion, it’s easier in this way…” (Account Representative Carrier North)

124 Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 – n° 33

Business Model Innovation in a Network Company

The Challenging Co-Existence of BMs and Conflicts in Inter-

Organizational Relationships

However, the agencies refrained from cooperating as expected, since

agencies tend not to share all information on the platform and do not allo-

cate loadings to dedicated trucks. In fact, cooperation between CH Robinson

Europe agencies tends to depend on fluctuations in the market price of trans-

port. European agencies compare the prices of the dedicated truck relative

to spot prices. When spot prices surpass the costs borne by an Agency when

chartering a dedicated truck, the Agency does not share information with

the other agencies and mobilizes the dedicated truck for its own shipments.

Conversely, as spot prices sink below the prices paid by the Agency for a

committed truck’s shipment, the other agencies from the network prefer to

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

work with the transporter at a spot price to earn a higher margin. Those

opportunistic behaviours not only affect the performance of the BMI but also

generate tension among CH Robinson Europe agencies.

“The dedicated truck is given priority over spot, and it is something that

has changed. But, it’s still a tough negotiation with colleagues (other CH

Robinson agencies). When you present your truck in the quiet period,

and that is necessarily more expensive than the spot, the other agency

does not necessarily want to open the trip, does not necessarily want to

share it with you.” (Client Manager)

In fact, the two BMs involve different content flows and governance

mechanisms inside relationships. Whereas BMI fosters cooperative and

reciprocal relationships as well as a formal mode of governance, the firm’s

BM, which is based on spot transportation, fosters one-shot relationships

based on a sharing of profit.

“But, the big difficulty … is especially having loads available from other

agencies…and sometimes it is very difficult because each agency is a

profit centre and wants to maximize its sales; it will not necessarily see

the dedicated truck as something sustainable.” (General Manager)

Moreover, challenges also occur in terms of relationships with external

partners. Thus, the BMI involves embedded and reciprocal relationships

between representatives from the transportation service within the CH

Robinson Europe network and with transporters. Consequently, it became

difficult to maintain the benefit from those same transporters of dedicated

trucks. Thus, relationship embeddedness lowers brokerage benefits, and the

following verbatim transcript illustrates this conflict:

n° 33 – Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 125

Amina Hamani, Fanny Simon

“The last years and with a flow that changes, the negotiations started

with the transporter three four years ago. Today, they are more to the

advantage of the transporter than to CH Robinson because prices made

with a single transporter in spot [on the spot] are more interesting than

things in [the] long-term (dedicated trucks).” (General Manager)

Once more, the transformation of inter-organizational relationships in

terms of structure and content alters the set of relationships that are needed

to conduct the traditional BM, and it was decided that the new project BM

should be deployed in a separate entity. Figure 3 synthesizes all the changes

that have been triggered in the network due to the deployment of the BMI.

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

The Disconnection Phase

In April 2016, a meeting among CH Robinson agency general manag-

ers was conducted to find a solution. Their reflection led them to consider

reshaping the network. The management of the dedicated truck would be

entrusted to a new agency independent of the other CH Robinson European

agencies. This new agency would be in charge of negotiating with the carri-

ers and supplying the entire CH Robinson Europe truck network with ship-

ments, which could resolve the conflict of interest between the agencies

based on obtaining and mobilizing the means of transport: “If we want to this

to really work, dedicated trucks organization must not be as it is now. It should be

in a completely separate unit and not dependent on agencies. Today, the dedicated

truck depends on a profit centre that has to make money. Dedicated trucks today

must make money, but it must not be associated with the agencies revenues within

agencies because there are conflicts of interest.” (General Manager)

The solution that was envisioned seems to sustain the claim that BMI

and a firm’s BM should be deployed as separate entities with little connec-

tion. The need for separation could be justified by the fact that different

governance modes and structures, in terms of relationships, are needed for

the two BMs.

However, in the end, the general managers decided not to set up this new

agency as of yet because they had not determined how the agency could be

managed in the future, particularly because of the unstable environment of

road transportation in Europe. To avoid conflicts of interest relative to the

BMI, the Agency has resumed going back and forth with the same truck and

the same driver instead of spreading that truck throughout Europe. However,

those trips are restricted to the Agency’s geographical zone and that of other

agencies with which the Agency has embedded relationships. This solution

126 Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 – n° 33

Business Model Innovation in a Network Company

can be qualified as a disconnection between the BMI and the firm’s initial

BM.

Discussion and Conclusion

Although the concept of the BM has attracted renewed interest from both

academic and professional communities, BMI has been given less emphasis

(Foss, Saebi 2017; Gassmann et al., 2016), whereas BM evolution is often a

powerful trigger to deploy change in organizations. Indeed, changing the BM

is central to creating sustainable values for business leaders and responding

to changes in their environment (Demil, Lecocq, 2010; Schneider, Spieth,

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

2013).

We bring new insights to the literature on BMI by using concepts from

the literature on innovation in inter-organizational networks. Current stud-

ies focus on changes within the firm and mostly do not consider the trans-

formations of external networks (Berglund, Sandström, 2013). The literature

on inter-organizational networks allows us to take into account modifications

of the structure, content and governance of the value networks, which may

conflict with the logic of the existing BM. Thus, an increase in the level of

embeddedness inside the network may be detrimental for the focal firm’s

value capture mechanisms, while changes in the flow of resources may ham-

per value creation within the network. Furthermore, we highlighted gover-

nance challenges, as BMI often requires specific structures of cooperation.

More particularly, we focus on the structure, content flow and coordina-

tion mechanisms inside networks. BMI requires changes to organizational

structure, coordination and control mechanisms, but these dimensions are

less explored (Foss, Saebi, 2017). BMI is often considered based on changes in

a single or more components. However, this literature is particularly suitable

for analysing BMIs because such an innovation requires the transformation

of exchanges among companies in the value network to generate new rev-

enue streams. It allows us to better understand the interdependencies and

complementarities that exist between the BM of different organizations. On

the one hand, complementarities with external partners’ BMs trigger a new

value proposition and allow a new allocation of tasks and resources between

the firm and its suppliers. Thus, the BMI emerges from specific relationships

with partners and, ultimately, allows value creation and capture for both the

focal firm and its partners. Consequently, the BMI was rapidly adopted and

could be deployed at a local level without formal agreement. On the other

hand, the interdependencies of the different firms’ BMs fell inside the net-

work organization constraint of BMI deployment. Hence, whereas value was

n° 33 – Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 127

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

Figure 3 – Inter-organizational relationship dynamics and the evolution of BMs

128

Amina Hamani, Fanny Simon

Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 – n° 33

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

Business Model Innovation in a Network Company

created for customers through new offerings and better quality, the mecha-

nisms for value capture inside the network were not clear. Eventually, the

BMI brought into question the revenue generation structure of the exist-

ing BM, and firms inside the network had to choose either to cooperate to

enhance the network’s overall profitability or to benefit from both BMs to

increase their own profit. This particular example demonstrates that the BMI

and the firms’ BMs were not aligned. Thus, enhancing revenue generation

for individual firms in the network do not always lead to the optimization

of value creation inside the network, as in our example; this would lead to a

certain potential for a truck’s loadings not to be shared across the network.

Consequently, it shows that a company set up under a BMI should assess the

interdependencies of that BM with other organizations’ BMs both at the firm

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

and the network levels.

Consequently, our article develops new insights into the literature on

BMI in a network organization by demonstrating that the new project can

differentially affect a local entity’s and the network firm’s BMs. The litera-

ture has already highlighted the complexity of new BM implementations in

a networked organization and, in particular, depicted several factors that may

hamper said implementation, such as the uncertainty of operational pro-

cesses, a lack of availability of resources, the lack of clarity among the stake-

holders’ strategic intent or their lack of consensus on operational aspects

(Solaimani et al., 2018). Our work reveals other factors that may also impede

the deployment of a BMI. In particular, it demonstrates that the lack of for-

mal governance mechanisms at the level of the network to organize resource

sharing (such as the availability of trucks) also plays a role at the network

level. Consequently, specific governance mechanisms may have to be set up

in a network organization to manage the allocation of new resources as BMIs

are deployed. Thus, our work allows a better understanding of interactions

among actors in a BMI, which have previously been overlooked (Wirtz et al.,

2016).

We also contribute to the debate on whether BMIs should be carried out

in a separate unit or connected to the main BM. Our findings indicate that a

BMI may be aligned with the agency’s BM but may also be disconnected from

its network’s BM. Our results are consistent with Khanagha et al.’s (2014)

work, which recognizes recursive iterations between different modes of sepa-

rated and integrated structures. We found that, at first, it seems that this

situation could lead to the creation of new structures supporting inter-organi-

zational BMIs, which would be in line with the literature on structural ambi-

dexterity (Raisch et al., 2009). Instead, we discovered that the deployment

of the BMI was suspended, and the exploratory BM was then disconnected

n° 33 – Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 129

Amina Hamani, Fanny Simon

from the network’s BM. Thus, studies on ambidexterity in networks or the

management of different types of ties to deploy exploratory and exploitative

activities in a network provide a better lens through which to understand the

performance of the BMI than do studies on structural ambidexterity.

Naturally, a single-case study cannot lead to definitive conclusions; how-

ever, our research indicates that the concept of network ambidexterity could

be an interesting notion by which to study BMI and answer challenges rela-

tive to the co-existence of BMs in networks. Indeed, building on the lit-

erature reviewed in this paper, our conclusion is that the literature on inter-

organizational relationships in innovation helps to understand the challenges

relative to the co-existence of BMs.

Our work presents one main limit, which deals with the network’s

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

boundaries. Thus, recent works point out that network company manag-

ers are adopting an ecosystemic representation of their inter-organizational

relationships (Chatterjee, Matzler, 2019; Demil et al., 2018; Warnier et al.,

2018). According to this representation, a focal company regroups different

actors, which represent groups or individuals who create and capture value

in the value network around a product, a resource or a technology, and coor-

dinate its relationships with those actors through platforms (Garcia-Castro,

Aguilera, 2015). Thus, ecosystems offer different opportunities to create and

capture value by establishing closer relationships and interacting with differ-

ent actors at the inter-organizational level (Chatterjee, Matzler, 2019; Demil

et al., 2018). It could then be interesting to consider the Navisphere system as

a broader platform for orchestrating the ecosystem and to carry out a detailed

study of the alignment of interests around that platform in line with Adner’s

(2017) work.

REFERENCES

ABDELKAFI, N., MAKHOTIN, S., POSSELT, T. (2013), Business Model Innovations

for Electric Mobility: What can be Learned from Existing Business Model Patterns?,

International Journal of Innovation Management, 17(1), 1340003.

ACHTENHAGEN, L., MELIN, L., NALDI, L. (2013), Dynamics of Business Models:

Strategizing, Critical Capabilities and Activities for Sustained Value Creation, Long

Range Planning, 46(6), 427-442.

ADNER, R. (2017), Ecosystem as Structure: An Actionable Construct for Strategy, Journal

of Management, 43(1), 39-58.

ALCALDE, H., GUERRERO, M. (2016), Open Business Models in Entrepreneurial Stages:

Evidence from Young Spanish Firms during Expansionary and Recessionary Periods,

International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(2), 393-413.

130 Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2020/3 – n° 33

Business Model Innovation in a Network Company

ALLEE, V. (2008), Value Network Analysis and Value Conversion of Tangible and

Intangible Assets, Journal of Intellectual Capital, 9(1), 5-24.

AMIT, R., ZOTT, C. (2015), Crafting Business Architecture: The Antecedents of Business

Model Design, Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 9(4), 331-350.

BANKVALL, L., DUBOIS, A., LIND, F. (2017), Conceptualizing Business Models in

Industrial Networks, Industrial Marketing Management, 60, 196-203.

BARNEY, J. B. (2018), Why Resource-based Theory’s Model of Profit Appropriation must

Incorporate a Stakeholder Perspective, Strategic Management Journal, 39(13), 3305-

3325.

BERGLUND, H., SANDSTRÖM, C. (2013), Business Model Innovation from an Open

Systems Perspective: Structural Challenges and Managerial Solutions, International

Journal of Product Development, 18(3-4), 274-285.

BÖRJESON, L. (2015), Interorganizational Situations : An Explorative Typology, European

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

© De Boeck Supérieur | Téléchargé le 27/11/2023 sur www.cairn.info via Université Catholique de Lyon (IP: 193.51.243.241)

Management Journal, 33(3), 191-200.

BOURCET, C., CEZANNE, C., RIGOT, S., SAGLIETTO, L. (2019), Le financement

participatif de projets d’énergies renouvelables (ENR): éclairages sur le modèle écono-

mique et les risques d’une plateforme française, Innovations, 59(2), 151-177.

CASADESUS-MASANELL, R., RICART, J. E. (2010), Competitiveness: Business Model

Reconfiguration for Innovation and Internationalization, Management Research:

Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 8(2), 123-149.

CHATTERJEE, S., MATZLER, K. (2019), Simple Rules for a Network Efficiency Business

Model: The Case of Vizio, California Management Review, 61(2), 84-103.

CHESBROUGH, H. (2007), Business Model Innovation: It’s not just about Technology

Anymore, Strategy & Leadership, 35(6), 12-17.

CHESBROUGH, H. (2010), Business Model Innovation: Opportunities and Barriers, Long

Range Planning, 43(2-3), 354-363.

CHESBROUGH, H., SCHWARTZ, K. (2007), Innovating Business Models with

Co-Development Partnerships, Research-Technology Management, 50(1), 55-59.

CLAUSS, T. (2017), Measuring Business Model Innovation: Conceptualization, Scale

Development, and Proof of Performance, R&D Management, 47(3), 385-403.

CLEGG, S., JOSSERAND, E., MEHRA, A., PITSIS, T. S. (2016), The Transformative

Power of Network Dynamics: A Research Agenda, Organization Studies, 37(3), 277-291.

DEMIL, B., LECOCQ, X. (2010), Business Model Evolution: in Search of Dynamic

Consistency, Long Range Planning, 43(2), 227-246.

DEMIL, B., LECOCQ, X., WARNIER, V. (2018), Business Model Thinking, Business

Ecosystems and Platforms: The New Perspective on the Environment of the

Organization, M@n@gement, 21(4), 1213-1228.

DHANARAJ, C., PARKHE, A. (2006), Orchestrating Innovation Networks, Academy of